by Rieke Trimçev, Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, and Friedemann Pestel

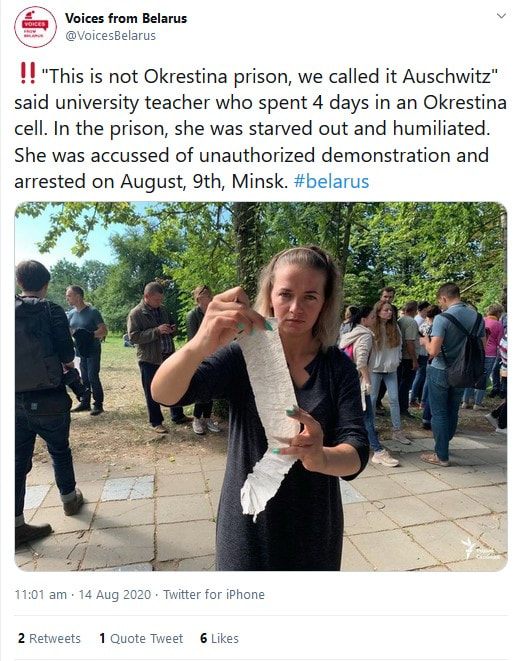

During the upheaval against Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus after the contested presidential election in August 2020, the idea of ‘Europe’ has often been invoked. These invocations might be surprising, given that Belarusians themselves have shunned explicit references to the EU and that EU flags were absent on the country’s streets. Instead, a rhetorical call to Europe has served to amplify demands for the support of Belarusian society and direct Europe’s attention to a country long-neglected by the international community. Lithuania’s former foreign secretary stated on Twitter: “The 21st century. The heart of Europe – Belarus. A criminal gang a.k.a. ‘Police Department of Fighting Organized Crime’ terrorizing Belarusians who have been peacefully demanding freedom and democracy for already 80 consecutive days. Shame!” Designating a particular region as “the heart of Europe” is a popular rhetorical device, acting as a way to call for attention. During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Margaret Thatcher used the metaphor to denounce the E.C.’s failure to prevent the mass killings in Bosnia: “this is happening in the heart of Europe […] It should be within Europe’s sphere of conscience.” The force of this phrasing defies geographical reality and lies in elevating specific values and principles as central to the idea of Europe. Europe’s political activity should live up to these values, simply to protect a vital part of its body. Through this formula, places like Belarus or Bosnia become part of a shared mental map, understood as a “spatialisation of meaning [that] dwells latently in the minds of individuals or groups of people.”[1] Another look at the rhetoric of the Belarusian protests indicates that shared representations of the past and the language of memory are particularly powerful tools in spatialising meaning and increasing the visibility of regional events for a transnational audience. All these tweets and pictures compare the Okrestina Detention Centre in Minsk, where many of the protesters were interned, to the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. Leaving aside the question of whether such comparisons are appropriate, their implication for protesters is clear: “The heart of Europe” is where Europe’s founding norm of “Never again!” is at risk.

The spatialised communication of normative arguments are at the core of our ongoing research project on the contested languages of European memory—“Europe’s Europes” if you will. It is informed by a larger qualitative study, in which we study public ideas of Europe through the prism of representations of the past and the language of memory. Examining press discourse in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2018, we have reconstructed several entrenched mental maps of Europe, which differ according to regional perspectives, ideological stances or historical trajectories. Some of these imaginaries—“Europe’s Europes”—complement each other, while others stand in open or implicit contradiction and provoke conflicts over the mental geography of Europe. To say that they are “entrenched” mental maps means that they are deeply rooted in everyday thought-behaviour and help to make sense of today’s political challenges. It is here that the language of memory, whose importance in forming shared senses of identity has long been noted, shows its ideological pertinence even beyond debates over memory politics strictly speaking.[2] Understanding these mental maps allows us to better seize discursive deadlocks, but also to identify missed encounters in debating in, over and with Europe. Islands of consensus The metaphor of the “heart of Europe” pictures Europe as a body whose different parts naturally work together to assure the functioning of a holistic “community of values”. While this metaphor might sound unsurprising, it turns out to be a concept that has a limited discursive reach, and is of limited agency when it comes to everyday political debates beyond grandiose speeches. In our study, we found that Europe is predominantly understood as a contested idea. Most of the deep-rooted mental maps spatialise this contestation through imaginary borders, both internal and external. Against the predominance of these fractured mental maps, ideas of Europe as a consensual community of values appear as “islands of consensus” of limited discursive reach. Between 2004 and 2018, one such “island of consensus” structured significant parts of the Italian press discourse, where Europe was pictured as a continent united through a canone occidentale, embracing Antiquity, Judaeo-Christian roots, Enlightenment, Liberalism, and other historical cornerstones with a positive connotation. This idea of a European canon also occurs in other national discourses but is more partisan. Especially in times of crisis, speaking from within a community of values has allowed for a clear yardstick of judgment. For example, the failure to set up a joint accommodation system for migrants in 2015, from the viewpoint of this mental map, appeared to betray European memory—a memory which had claimed a humanitarian impetus when boatpeople had fled from communism in the 1970s and 1980s: “On the issue of immigration, the Europe of the single currency and strengthened political governance seems less cohesive and less aware than Europe at the time of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War. The memory of the new Europeans and the new ruling classes seems indifferent to recent history.”[3] Yet, the moral self-confidence of dwellers of an island of consensus comes at some cost. From the perspective of an island of consensus, conflicts appear as a misunderstanding that could be solved by proper integration, inclusive of a European memory. However, this perspective remained largely confined to Italy and found little echo in other discursive spheres. Frictions between ‘East’ and ‘West’ A particularly prominent way of spatialising the meaning of Europe revolves around an East-West divide. While it is prominent both in ‘old Europe’ and those post-communist countries that joined the EU in 2004, it must be understood as the junction of two different, and in fact competing mental mappings. For France and Germany, ‘Eastern Europe’ largely represents a mnemonic terrain on which, after 1945, the communist regimes froze the memories of World War 2 and the Holocaust, and which still today rejects communist rule as an external imposition on its societies. Hence, post-communist societies are expected to catch up with the successful travail de mémoire or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which are associated with Western European societies. The ‘West’ is pictured as a spring of impartial rules for facing the past, rules that might in principle flow into the Eastern periphery to resuscitate withered memories. This even seems a precondition for the kind of dialogue suitable for bridging the often-decried East-West divide. From a Polish perspective however, the question of an East-West divide is not one of rules for remembering, but about determining a factual historical truth. “For Western elites it is difficult to accept that history for Eastern Europeans does not end with Hitler and the extermination of the Jews.”[4] It is the recognition of these truths and the national histories of suffering that is seen as the precondition of dialogue. From the perspective of this mental map, historical analogies can also serve to strengthen Poland’s position in the EU, for instance, when Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk likened Germany’s North Stream 2 pipeline to the Hitler-Stalin-Pact that had divided Poland and all of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. As the pipeline was “precisely such an agreement over the heads of others,”[5] it appeared impossible in the context of European integration in the 21st century. Periphery or boundary? Another entrenched way of mapping Europe proceeds not from its internal divisions, but from its external demarcation: Where does Europe end, or, how far does Europe reach? Again, in public discourse, asking this question serves to spatialise the strife over Europe’s core values. Over the 2000s and 2010s, the position of Turkey on Europe’s mental map has been the occasion to answer this question. And as for the East-West divide, what we observe is in fact a competition between two mental maps. From an affirmative perspective, Europe represents a clearly demarcated space, based either on conservative values such as its “Christian roots” or radical Enlightenment principles which are framed as universal and secular values. A test case for the latter was the recognition of the mass killing of 1,5 million Armenians as genocide—Europe had to end where this recognition was refused. French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy, at that point in favour of Turkish EU-membership, formulated the point very clearly: “amongst the criteria fixed by Brussels for the Turkish entry into the European Union, the most important condition is lacking: the recognition of the Armenian genocide. . . . During the genocide, Turkey attempted to amputate itself of its European part. This was a genocide, and a suicide.”[6] From the viewpoint of a competing mental map, Europe appeared rather as an open space, reflexive of its own history and its cultural, historical, and religious diversity. The political motives supporting the image of such an open Europe were highly heterogeneous. From a British viewpoint, Turkey’s EU membership ambitions represented a welcome occasion for renegotiating power relations within the EU and allowed the UK to articulate more utilitarian attitudes towards European integration. For Polish conservatives, Turkey presented an alternative to a model of integration marked by secularisation and unquestioned Westernisation. Instead of further secularising Turkey, they favoured a religious turn in European integration. Accordingly, the “conservative Muslim” went to the mosque on Fridays and “the conservative Pole” to church on Sundays.[7] Jeux d’échelles A last way of mapping Europe becomes evident in the question of how Europe links to the global context. This question is of particular importance in British discourse, where memories of the Empire project a national mnemonic order onto Europe. It is noteworthy indeed that other post-imperial countries such as France, Germany, Spain or Italy do not develop on this global component through a discussion of their past. Theresa May’s call for a “truly global Britain” which had the ambition “to reach beyond the borders of Europe” testifies to how, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, British spatial imaginaries were pitted against Europe, often referencing the UK’s more flexible economy as much as the historical grandeur of a Britain before European integration. Other countries explicitly reject such framings, but do not include perspectives from outside an alleged Europe either. The discourse on ‘European memory’ mostly relied on the ‘world’ to talk exclusively about Europe. Diverging ideas of Europe beyond conflict and consensus Mental maps of European memory stake claims of what constitutes Europe, who belongs to it and where the continent ends. In the mental maps sketched out here consensus is restricted to Sunday-best speeches and the Italian canone occidentale that exemplifies a form of model Europeanism. In contrast, the other spatial imaginations rely on the conflictive character of ‘European memory’ and demarcate the continent from an internal, external or global other. These findings provide a deeper understanding of European memory underpinning ideas of European integration and may also serve for further analysis of conflicts over the idea of Europe itself. In our future research, we will inquire into the diachronic shifts of these mental maps: they reveal the entangled relation between European integration and disintegration as scenarios for a future Europe. [1] Norbert Götz and Janne Holmén, ‘Introduction to the theme issue: “Mental maps: geographical and historical perspectives”’, Journal of Cultural Geography 35(2) (2018), 157. [2] Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, Daniela Mehler, Friedemann Pestel, and Rieke Trimçev, Europäische Erinnerung als verflochtene Erinnerung – Vielstimmige und vielschichtige Vergangenheitsdeutungen jenseits der Nation (Formen der Erinnerung 55) (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht unipress), 2014. [3] ‘Sfide dopo il no di Londra’, Corriere della Sera, 18.05.2015. [4] ‘Stalinizm jak nazizm’, Rzeczpospolita, 23.02.2008. [5] https://emerging-europe.com/news/polish-minister-compares-nord-stream-2-with-molotov-ribbentrop-pact/ [6] ‘Ma non si può parlare di adesione se non si scioglie il nodo del passato’, Corriere della Sera, 23.1.2007. [7] ‘Masowa imigracja to masowe problemy’, Rzeczpospolita, 25.07.2015. by Juliette Faure

Since the mid-2010s, ‘tradition’ has become a central concept in political discourses in Russia. Phrases such as ‘the tradition of a strong state’, ‘traditional values’, ‘traditional family’, ‘traditional sexuality’, or ‘traditional religions’ are repeatedly heard in Vladimir Putin’s and other high-ranking officials’ speech.[1] Paralleling a visible conservative rhetoric hinging on traditional values, the Russian regime demonstrates a clear commitment to technological hypermodernisation. The increased budget for research and development in technological innovation, together with the creation of national infrastructures meant to foster investments in new technologies such as Rusnano or Rostec, and the National Technology Initiative (2014) show a firm intent from the regime.

At the level of official rhetoric, the conservative conception of social order conflicts with a progressive politics of technological modernisation. The Russian president blends a traditionalist approach to social norms based on a fixed definition of human nature,[2] and a liberal approach to technological modernisation emphasising the ideas of innovation, change, speed, acceleration, and breakthrough.[3] The concept of tradition entails cultural determinism and heteronomy: individuals are bounded by a historical heritage and constrained by collective norms. On the contrary, technological modernisation relies on a constant development that strives to push back the limits of the past and nature. In fact, recent studies of science and technology in the post-war USSR increasingly document the positively correlated relations between technoscientific modernisation and political liberalisation. Scientific collaboration with the West,[4] the importation of standards,[5] the multiplication of ‘special regimes’ for scientific communities,[6] and the objectivisation of decision-making through the use of computer science and cybernetics[7] have contributed to the erosion of the Soviet system’s centralisation,[8] the normalisation of its exceptionalism, and its ultimate liberalisation. The USSR arguably failed to sustain itself as a ‘successful non-Western modernity’.[9] The Soviet experience therefore substantiated the technological determinism assumed by liberal-democratic convergence theories.[10] Despite that, there has recently been an increasingly visible effort by contemporary Russian conservative intellectuals to overcome the dichotomy between authoritarian–traditionalist conservatism and technological modernity in order to coherently articulate them into a single worldview.[11]This form of conservatism was already advocated in the late Soviet period by the journalist and writer Aleksandr Prokhanov (1938–). In the 1970s, Prokhanov opposed the domination, among the conservative ‘village prose’ writers, of the idealisation of the rural past and the critique of Soviet modernity.[12] Instead, he aimed to blend the promotion of spiritual and cultural values with an apology of the Soviet military and technological achievements.[13] After the fall of the USSR, Prokhanov’s modernism became commonplace among the members of the younger generation of conservative thinkers, born around the 1970s.[14] Young conservatives framed their views in the post-Soviet context, and regarded technological modernity as instrumental for the recovery of Russia’s status as a great power. One of the leading members of the young conservatives, Vitalii Averianov (1973–), coined the concept of ‘dynamic conservatism’ to describe their ideology. This ideology puts forward an anti-liberal conception of modernity where technology serves the growth of an authoritarian state power and a conservative model of society. Unlike classic conservatism, ‘dynamic conservatism’ resembles the type of political ideology that Jeffrey Herf identified, in the context of Weimar Germany, as ‘reactionary modernism’.[15] The intellectual origins of ‘dynamic conservatism’ across generations of conservative thinkers: Vitalii Averianov and Aleksandr Prokhanov In 2005, ‘dynamic conservatism’ served as the programmatic basis of one of the major contemporary conservative collective manifestos, the Russian Doctrine, co-authored by Vitalii Averianov, Andrei Kobiakov (1961–), and Maksim Kalashnikov (1966–) with contributions from about forty other experts.[16] The Doctrine was put forward as a ‘project of modernisation of Russia on the basis of spiritual and moral values and of a conservative ideology’.[17] The leading instigator of the Doctrine, Averianov, described the ideology advocated by the Russian Doctrine as follows: 'The purpose of the proposed ideology and reform agenda is to create a centaur from Orthodoxy and the economy of innovation, from high spirituality and high technology. This centaur will represent the face of Russia in the 21st century. His representatives should be a new attacking class—imperial, authoritarian, and not liberal-democratic. This should be the class that will support the dictatorship of super-industrialism, which does not replace the industrial order but grows on it as its extension and its development.'[18] In his essay Tradition and dynamic conservatism, Averianov further explains that the ‘dynamic’ aspect of conservatism comes from two paradigmatic shifts that occurred in 20th century’s Orthodox theology and history of science[19]. Firstly, he resorts to the theologian Vladimir Lossky’s (1900–1958) concept of the ‘dynamic of Tradition’. Vladimir Lossky developed this concept in order to address and reform what he perceived as the Orthodox Church authorities’ formal traditionalism and historical inertia. Secondly, Vitaly Averianov appeals to the work of the physicist and Nobel laureate Ilya Prigogine (1917–2003). According to him, the discovery of non-linear dynamic systems disclosed the ‘uncertain’ character of science and offers a post-Newtonian, post-mechanic, and ‘unstable’ view of the world[20]. As Averianov puts it: ‘We situate ourselves at the intersection between Orthodox mysticism and theology, which are embodied by Lossky, who coined the term [of dynamic conservatism], and on the other hand, systems theory and synergetics.’[21] In 2009, the authors of the Russian Doctrine convened in the ‘Institute for Dynamic Conservatism’, which subsequently merged with the ‘Izborsky Club’ founded in 2012 by Aleksandr Prokhanov.[22] Born in 1938, Prokhanov is a well-known figure in Russia as one of the leading ideologues of the putsch against Gorbachev’s regime in August 1991, as a prolific writer of more than sixty novels, and as the current editor-in-chief of the extreme right-wing newspaper Zavtra. In 2006, he articulated a theory about the restoration of the Russian ‘Fifth Empire’, according to which the new Russian ‘imperial style’ should combine ‘the technocratism of the 21st century and a mystical, religious consciousness’.[23] More recently, Prokhanov adopted Averianov’s formula, ‘dynamic conservatism’, to describe his own worldview, which is meant to ‘ensure the conservation of resources, including the moral, religious, cultural, and anthropological resources, for modernisation’.[24] Prokhanov’s reactionary modernism is rooted in the Russian philosophical tradition of ‘Russian cosmism’, which regards scientific and technological progress as humanity’s instruments to achieve the spiritualisation of the world and of human nature.[25] The philosopher Nikolai Fedorov, regarded as the founding figure of Russian cosmism, offered to use technological progress and scientific methods to materialise the Bible’s promises: the resurrection of the dead, the immortality of soul, eternal life, and so on. Fedorov articulated a scientistic and activist interpretation of Orthodoxy, according to which humanity was bound to move towards a new phase of active management of the universe, thereby seizing its ‘cosmic’ responsibility.[26] Following on from Fedorov, 20th-century scientists such as Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, the ‘grandfather’ of the Soviet space programme, or Vladimir Vernadskii, the founder of geochemistry, also belong to the collection of authors gathered under the name ‘Russian cosmism’, since they too advocated a ‘teleologically-oriented’ vision of technological development.[27] Prokhanov and other Izborsky Club members claim the legacy of Russian cosmism in their attempt to craft a specifically Russian ‘technocratic mythology’, as an alternative to the Western model of development.[28] A strategic ideology branded by a lobby group at the crossroads of intellectual and political milieus Introduced as a rallying ‘imperial front’ for the variety of patriotic ideologues of the country (neo-Soviets, monarchists, orthodox conservatives), the Izborsky Club seeks to ‘offer to the Russian government and public […] a new state policy with patriotic orientation’.[29] With more than fifty full members and forty associated experts—including academics, journalists, economists, scientists, ex-military, and clerics[30]—the Club gathers together the largest group of conservative public figures in contemporary Russia. Aleksandr Dugin (1962–), the notorious Eurasian philosopher, is one of its founding members.[31] Despite Dugin’s promotion of Orthodox traditionalism and his critique of technological modernity, his membership of the Club was based on his long-standing relationship with Prokhanov.[32] In this new context of their ideological alliance, Valerii Korovin (1977–), Dugin’s younger disciple and another member of the Izborsky Club, has spelled out a reformed understanding of traditionalism, which regards technological modernity as an instrument for the promotion of Russia as an imperial great power in confrontation with the West: 'We have to separate scientific and technical modernisation and its social equivalent. There is a formula that Samuel Huntington introduced—‘Modernisation without Westernisation’. Russia is developing scientific and technical progress! Our scientists are the best in the world. They create breakthrough technologies. With this, we achieve modernisation while rejecting all Western delights in the field of human experiments. That is—no liberalism, no Western values, no dehumanisation, no mutants, clones, and cyborgs!’[33] In spite of its ideological variety, the Izborsky Club therefore put forward a ‘traditionalist technocratism’ or the ‘combination of ultramodern science with spiritual enlightenment’ as stated in one of its roundtables in September 2018,[34] or as a glance at the Club journal’s iconography rapidly evinces.[35] In blunt opposition to democratic convergence theories, the Izborsky Club brands dynamic conservatism as a strategic ideology for Russia’s development as a great power. The concept of ‘dynamic conservatism’ goes further than simply challenging the normative argument of Francis Fukuyama’s modernisation theory. It also contradicts its empirical claim, which contends that democracy is the regime naturally propelled by the development of modern natural science. Indeed, Fukuyama argues that the success of ‘the Hegelian-Marxist concept of History as a coherent, directional evolution of human societies taken as a whole’ lies in 'the phenomenon of economic modernisation based on the directional unfolding of modern natural science. This latter has unified mankind to an unprecedented degree, and gives us a basis for believing that there will be a gradual spread of democratic capitalist institutions over time.'[36] Based on this technological determinism, liberal modernisation theories claim that economic modernisation, especially in its latest innovation and information based ‘post-industrial’ phase, is incompatible with an authoritarian regime and central planning.[37] What is more, liberal-democratic modernisation’s theorists expect that a ‘post-industrial society’ would eventually lead to the convergence of societies and the ‘end of ideology’.[38] By contrast, ‘dynamic conservatism’ holds that the success and performance of the Russian techno-scientific innovation complex requires the strengthening of the state’s sovereignty under an authoritarian power. They oppose what they perceive as ‘the myth of post-industrialism, aimed at undermining and permanently destroying the real industrial sector of the domestic economy’,[39] and instead advance the need for ‘super-industrialism’ and total ideological mobilisation.[40] In this endeavour, Izborsky Club members frequently refer to the Chinese experience as a lasting challenge to the technological determinism described by liberal modernisation theories. They have voiced their admiration for China’s ability to maintain state ownership and state control in the organisation of its economy. Furthermore, they seek inspiration in China’s process of defining a national idea, the ‘Chinese dream’, combining a ‘harmonious society’ and a technologically advanced economy.[41] Likewise, the Izborsky Club advocates a vision of a ‘Russian dream’ based on a national-scientific and spiritual mythology as an alternative to the ‘American dream’.[42] The Izborsky Club has secured close ties with political, military, and religious elites.[43] The Club’s foundation in 2012 was supported by Andrei Turchak (1975–), who was at the time the governor of the region of Pskov and is now the Secretary-General of the ruling party ‘United Russia’.[44] Moreover, the Club received a financial grant from the presidential administration in its first years of operation. Members of the government or of the presidential administration have often attended the Club’s roundtables and discussions.[45] The Club also entertains close ties with governors and regional political elites in the federal districts, where it has established about twenty local branches.[46] The ideology of dynamic conservatism has also attracted the interest of the Russian Orthodox Church’s authorities. Vitalii Averianov’s experience working for the Church as the former chief editor of the newspaper ‘Orthodox Book Review’ and as chief developer of the most read Orthodox website Pravoslavie.ru, has been key to engaging with the Church at the time of the publication of the Russian Doctrine. Patriarch Kirill (1946–), then Metropolitan and chairman of the Church’s Department of External Relations, displayed public support for the doctrine. In 2007, when discussing the text at the World Russian People’s Council, a forum headed by the Orthodox Church, he declared: ‘This is a wonderful example of Russian social thought of the beginning of the 21st century. I believe that it contains reflections that will still be interesting to people in 10, 15, and 20 years. In addition to purely theoretical interest, this document could have practical benefits if it became an organic part of the national debate on the basic values of Russia.’[47] Finally, the Izborsky Club is vocal about its proximity with the military-industrial complex. The rhetoric, symbols, and iconography used by the Club in its publications portray the army as the natural cradle of the ‘Russian idea’ that they advocate for: ‘Our present military and technical space is the embodiment of the Russian dream.’[48] Beside Prokhanov’s declarations, such as ‘The Izborsky club will help the army prevent an “Orange revolution” in Russia’,[49] actual cooperation with the military-industrial complex has been demonstrated by the regular organisations of the Izborsky Club’s meetings in military-industrial factories. Also significantly, in 2014, a Tupolev Tu-95 bomber was named after the Izborsky Club and decorated with its logo, thereby following the Soviet tradition of naming military airplanes after famous national emblems.[50] In today’s Russia, the patriotic, spiritualised ideology of technological development has been increasingly able to compete with the secular and Western-oriented liberal socio-technical imaginary. This polarity is brought to light by the leadership of technology-related state corporations. The nomination of Dmitrii Rogozin (1963–) as the head of Roscosmos, the state corporation for space activities, in 2018, contrasted with the nomination of Anatolii Chubais (1955–) as the head of Rusnano, the government-owned venture in charge of investment projects in nanotechnologies, in 2008. While Chubais is a symbolic representative of the Russian liberals, as vice-president of the government in charge of the liberalisation and privatisation program of the post-Soviet economy during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency, Dmitrii Rogozin is one of the key leaders of the conservative political elites. He is the former deputy prime minister in charge of defence industry (2011–18), the co-founder of the far-right national-patriotic party Rodina, and a close ally of the Izborsky Club.[51] In line with the agenda advocated by the Izborsky Club, Rogozin has been an active promoter of a nationalist, romantic, and messianic vision of the Russian space programme. According to him: ‘The Russian cosmos is a question of the identity of our people, synonym for the Russian world. For Russia cannot live without space, outside of space, cannot limit the dream of conquering the unknown that drives the Russian soul.’[52] While Vladimir Putin’s discourse runs through a wide and heteroclite ideological spectrum spreading from traditional conservative social values to neoliberal policies of technological development, the ideology of the Izborskii Club flourishes in specific niches in the ruling elites. The impact of their vision on the direction Russia is taking relies on the balance of power negotiated among these elites. [1] Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 12 December 2012, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/17118; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 12 December 2013, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/19825; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 4 December 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/47173; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 1 December 2016, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/53379. [2] See for instance his references to the Russian people’s ‘genetic code’ and ‘common cultural code’. Vladimir Putin, ‘Direct Line with Vladimir Putin’, President of Russia, 17 April 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20796. [3] This liberal-progressive vocabulary was particularly dominant in Vladimir Putin’s March 2018 address to the Federal Assembly. The discourse included 12 occurrences of the word ‘breakthrough’ (‘proryv’), 60 occurrences of the word ‘development’ (‘razvitie’), 10 occurrences of the word ‘change’ (‘izmenenie’) and 40 occurrences of the word ‘technology’ (‘tekhnologiia’). Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 1 March 2018, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957. [4] In 1972, the creation of the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis in Austria provided a place for scientific collaboration between the United States and the USSR until the late 1980s. See Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, The Power of Systems: How Policy Sciences Opened up the Cold War World (Ithaca ; London: Cornell University Press, 2016); Jenny Andersson, The Future of the World: Futurology, Futurists, and the Struggle for the Post Cold War Imagination (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018). [5] As evidenced by the participation of Soviet delegates in the meetings of the Hasting Institute and the Kennedy Center in the United States to establish an ethical framework on biotechnology, and the USSR’s adoption of the DNA manipulation rules of the US National Institute of Health that were established at the Asilomar Summit. Loren R. Graham, ‘Introduction: The Impact of Science and Technology on Soviet Politics and Society’, in Science and the Soviet Social Order, ed. Loren R. Graham (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Pr, 1990), 1–16. [6] Kevin Limonier, Ru.Net: Géopolitique Du Cyberespace Russophone, Carnets de l’Observatoire (Paris : Moscou: Les éditions L’Inventaire ; L’Observatoire, centre d’analyse de la CCI France Russie, 2018). [7] Slava Gerovitch, From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002). [8] Egle Rindzevičiūtė, ‘The Future as an Intellectual Technology in the Soviet Union - From Centralised Planning to Reflexive Management’, Cahiers Du Monde Russe 56, no. 1 (March 2015): 111–34. [9] This argument is developed by Richard Sakwa : ‘the Soviet developmental experiment represented an attempt to create an alternative modernity, but in the end failed to sustain itself as a coherent alternative social order’. See Richard Sakwa, ‘Modernisation, Neo-Modernisation, and Comparative Democratisation in Russia’, East European Politics 28, no. 1 (March 2012): 49; Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, ‘The Civilizational Dimension of Modernity: Modernity as a Distinct Civilization’, International Sociology 16, no. 3 (September 2001): 320–40. [10] As famously articulated in Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York : Toronto : New York: Free Press ; Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; Maxwell Macmillan International, 1992); Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (New York: Basic Books, 1973); Daniel Bell, The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties: With a New Afterword (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988). [11] This argument was also formulated by Maria Engström in Maria Engström, ‘“A Hedgehog Empire” and “Nuclear Orthodoxy”’, Intersection, 9 March 2018, http://intersectionproject.eu/article/politics/hedgehog-empire-and-nuclear-orthodoxy. [12] On the ‘village prose’ movement and the different forms of conservatism in the late Soviet Union, see Yitzhak M. Brudny, Reinventing Russia: Russian Nationalism and the Soviet State, 1953-1991, Russian Research Center Studies 91 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998). [13] See Juliette Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), published online at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13569317.2021.1885591. [14] On the younger generation of Russian conservatives, see Alexander Pavlov, ‘The Great Expectations of Russian Young Conservatism’, in Contemporary Russian Conservatism. Problems, Paradoxes, and Perspectives, ed. Mikhail Suslov and Dmitry Uzlaner (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2020), 153–76. [15] Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). [16] See the list of experts and contributors involved in the writing of the Doctrine: http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95506.html [17] ‘Russkii Sobor Obsudil Russkuiu Doktrinu’, Institute for Dynamic Conservatism (blog), 21 July 2007, http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95525.html. [18] Vitalii Averianov, ‘Nuzhny Drugie Liudi', Zavtra, 14 July 2010, http://zavtra.ru/blogs/2010-07-1431. [19] Vitalii Averianov, ‘Dinamicheskii Konservatism. Printsip. Teoriia. Ideologiia.’, Izborskii Klub (blog), 2012, https://izborsk-club.ru/588. [20] In Order Out of Chaos : Man’s New Dialogue with Nature, that he co-authored with Isabelle Stengers, Ilya Prigogine concludes that science and the ‘disenchantment of the world’ are no longer synonyms. See Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers, Order out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature (London: Flamingo, 1985). [21] Averianov, ‘Dinamicheskii Konservatism. Printsip. Teoriia. Ideologiia.’, art. cit. [22] On the Izborsky Club, see Marlène Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, The Russian Review 75 (October 2016): 634. [23] Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Imperskii Stil’, Zavtra, 30 October 2007, http://zavtra.ru/blogs/2007-10-3111. [24] Quoted in Dmitrii Melnikov, ‘"Valdai" na Beregakh Nevy’, Vesti.ru (2012) : https://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=944192&cid=6 [25] Juliette Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, The Conversation (2021): https://theconversation.com/russian-cosmism-a-national-mythology-against-transhumanism-152780. [26] George Young, The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). [27] Michael Hagemeister, ‘Russian Cosmism in the 1920s and Today’, in The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, Bernice G. Rosenthal (Ed.) (Ithaca ; New York: Cornell University Press, 1997). [28] Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, art. cit. [29] See the ‘about us’ page of the Izborsky Club’s website: https://izborsk-club.ru/about. [30] Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, 634. [31] Other prominent members of the Izborsky Club include the economist Sergei Glaziev, the Nobel Prize physicist Zhores Alferov (1930-2019), Metropolitan Tikhon Shevkunov, the writers Iurii Poliakov and Zakhar Prilepin, leading journalists for Russia’s TV ‘Channel One’ such as Maksim Shevchenko or Mikhail Leontev, who is also the press-Secretary for the state oil company Rosneft. [32] See Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, art. cit., p. 9. [33] ‘Na Iamale Otkrylos Otdelenie Izborskogo Kluba', Izborskii Klub (blog), 1 April 2019, https://izborsk-club.ru/16727. [34] ‘Stenogramma Kruglogo Stola Izborskogo Kluba "V Poiskakh Russkoi Mechty i Obraza Budushchego"’, Izborskii Klub (blog), 10 October 2018, https://izborsk-club.ru/15978. [35] See for instance the cover pages of the Club’s journal 2018 issues : https://izborsk-club.ru/magazine#1552736754837-283c3fe0-bb20 [36] Francis Fukuyama, ‘Reflections on the End of History, Five Years Later’, History and Theory 34, no. 2 (May 1995): 27. [37] Francis Fukuyama reformulates Friedrich Hayek’s argument. See Friedrich Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’, The American Economic Review 35, no. 4 (1945): 519–30. The compatibility between a centralised and authoritarian political system and the development of an economy of innovation was however considered by Joseph Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942, Harper & Brothers). [38] Bell, The End of Ideology, op. cit.; Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society, op. cit. [39] Averianov, ‘Nuzhny Drugie Liudi', art. cit. [40] According to Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘without ideology, there is no state at all’, see Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Raskol Intelligentsii’, Institute for Dynamic Conservatism Website, 11 October 2013, http://dynacon.ru/content/articles/2039/. [41] See for instance Aleksandr Nagornii, ‘Kitaiskaia Mechta Dlia Rossii', Izborskii Klub (blog), 9 April 2013, https://izborsk-club.ru/1130. [42] Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, art. cit. [43] Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, art. cit. [44] The ‘about us’ section of the Izborsky Club website writes : ‘The governor of the Pskov Region A.A. Turchak played an important role in the creation of the Club.’ See : https://izborsk-club.ru/about [45] For instance, the Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinskii took part in the inauguration ceremony of the Club in September 2012. [46] For a list of the Izborky Club delegations in the regions, see : https://izborsk-club.ru/contacts [47] ‘Vsemirnii Russkii Narodnii Sobor Rassmatrivaet "Russkuiu Doktrinu" v Kachestve Natsionalnogo Proekta'’, 28 June 2007, http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95531.html. [48] ‘Stenogramma Kruglogo Stola Izborskogo Kluba "V Poiskakh Russkoi Mechty i Obraza Budushchego"’, art. cit. [49] Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Izborskii Klub Pomozhet Armii Predotvratit "Oranzhevuiu Revoliutsiiu" v Rossii', Izborskii Club (blog), 13 March 2019, https://izborsk-club.ru/16616. [50] Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, art. cit. [51] Rogozine has founded the Rodina Party with Sergei Glaziev, a permanent and founding member of the Izborsky Club. Regarding his strong personal relationship with Aleksandr Prokhanov, see Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Strategicheskii Bombardirovshchisk “Izborskii Club”’, Zavtra, August 21, 2014, http://zavtra.ru/content/view/strategicheskij-bombardirovschik-izborskij-klub/. [52] Dmitrii Rogozin, ‘Rossiia Bez Kosmosa Ne Mozhet Ispolnit Svoi Mechty', Rossiiskaia Gazeta, 11 April 2014, https://rg.ru/2014/04/11/rogozin.html. 1/3/2021 Wandering ideas in the Age of Revolution: A case-study in how ideologies form and disappearRead Now by Piotr Kuligowski and Quentin Schwanck

In numerous studies, the 19th century is identified as the dawn of modern politics, for it was then that contemporary political ideologies emerged and/or gained popularity outside the narrow circles of intellectuals. Indeed, the rise of capitalism and the entanglement of deep social and economic phenomena then paved the way for new comprehensive ways of thinking and perceiving the world. This intellectual process gained a particular momentum in the period that Eric J. Hobsbawm correctly called ‘the age of revolution’ (roughly 1789–1848).[1] It was in this period that numerous authors clustered together novel single concepts such as ‘liberalism’ and ‘socialism’ to create all-encompassing intellectual systems. These conceptual constellations subsequently allowed political actors to grasp the entirety of socio-political phenomena and recognise them within the framework of a well-ordered system of thinking.

Yet how and why could French political concepts penetrate Polish discourse and contribute to the emergence of a distinct national ideology? And how do ideologies disappear?—these are two crucial questions we have addressed in our recent research. To tackle these questions, we combined research toolkits provided by ideology studies in the way proposed by Michael Freeden and his followers,[2] as well as the methods elaborated by the representatives of German conceptual history (Begriffsgeschichte).[3] Therefore, we perceive ideologies as relative stable galaxies of concepts (following Freeden’s definition of concepts as the ‘building blocks of ideology’)—even though, as happens in the cosmos, certain changes may occur from time to time: supernovae explode, meteorites fall, and stars and planets collide. In other words, our perspective allowed us—by tracing the transfers and transformations of individual concepts—to grasp the moment of the emergence and disappearance of the ideology we are interested in. In our case study we underline the role played by the asymmetrical pair of counter-concepts ‘individualism-socialism’, coined initially by the French philosopher Pierre Leroux (1797–1871), within the discourse of Polish democrats in exile. Indeed, despite the highly divergent sociopolitical conditions that obtained in Poland and France at the time, in the wider picture it is possible to observe certain common points and problems they intended to face. In particular, both Polish and French political actors from that time perceived the world as being in turmoil, and sought effective remedies to cure fears related to the modernising world. An important watershed in this story is the year 1830—a year of revolution in France, which also marked the outbreak of the anti-Russian November Uprising in the Russian-controlled part of Poland. Both events triggered profound changes in these countries’ political landscapes. Indeed, the case of post-1789 France is particularly interesting. During the first decades of the 19th century, many French thinkers, and particularly the first socialists, acknowledged the radical changes faced by society, that is to say the collapse of political legitimacy, the contestation of religious values, and the emergence of the question sociale in the wake of liberalisation and industrialisation. Trying to describe and analyse the new human condition, early socialist thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and their successors decisively contributed to shaping modern political categories. Their critique of the existing order led them to define the two great ideological alternatives that we still know today as socialism and liberalism, elucidating this opposition with the articulation of decisive counter-concepts. In this article, we investigate one of the most interesting cases of this ideological process, focusing on Pierre Leroux—the first French thinker to use the concept of socialisme. Leroux began to formulate his original philosophy in the 1830s and, although he was largely forgotten after the rise of scientific socialism, he greatly contributed to the political and social debate in the 19th century. As he insisted in 1857, it was he ‘who first used the word socialisme. It was then a neologism, a necessary neologism [coined] in contrast to individualisme, which was beginning to prevail.’ Indeed, in his periodical publications such as the Revue encyclopédique (1831–1833) and the Encyclopédie Nouvelle (1833–1840), but also in many of his books, Leroux formulated an innovative social philosophy based on the pair of counter-concepts individualisme and socialisme. He originally defined both terms in a pejorative fashion to describe the most extreme expressions of liberté and égalité, that is to say, atomisation and authoritarianism (referring to hierarchical forms of socialism such as Saint-Simonism): his objective being to find the golden mean between them. Finally, Leroux adopted a positive defition of socialism on the grounds that he considered this notion to be the best one to describe his philosophy, asserting that ‘we are socialists if one calls socialism the doctrine which will not sacrifice any of the words of the formula liberté, fraternité, égalité, unité, but which will conciliate all of them.’ By doing so, he conferred a deep political dimension on this concept, and argued that the only way for a nation to become socialist was to be democratic. Indeed, democracy was for Leroux the true regime of the golden mean: as all voices would be heard and all social energies would be expressed in the democratic debate, tensions would gradually fade and the oppositions would converge in a higher state of harmony. Pierre Leroux never became an ideological leader as he did not create a party or school of thought, but his original philosophy exerted a great influence on the 19th-century intellectual stage. His theory of democracy enabled him to become the first thinker to establish a fruitful dialogue between socialism and republicanism, thus becoming the great pioneer of republican socialism, an ideological stance and sensibility which played a great role in 19th- and 20th-century France. Furthermore, his doctrine gained a considerable audience at the European level, particularly in the small circles of the reformist elite. Indeed, as Leroux was a very close friend and interlocutor of George Sand, many of his most central ideas were presented or debated in her novels. As Sand was then the most famous female writer on the European continent, as well as an inspiration for many socialist movements, she enabled Leroux’s ideas to reach European intellectuals such as Alexander Herzen (1812–1870), Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872), and Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), making him a central figure to evaluate the impact of ‘wandering ideas’ in 19th-century Europe. In turn, the November uprising (that was finally defeated in 1831) marks a new period for Polish history, in which the massive emigration of cultural and political elites to Western Europe began. This phenomenon is called the Great Emigration, which had a profound impact on Polish culture (notably literature and poetry); but at the same time, its impact on the modernisation of the Polish political imagination should also not be underestimated. One of the political milieus of crucial importance that emerged amidst the waves of Polish emigration was the Polish Democratic Society. The Society was created in 1832 in Paris in the wake of a split within the Polish National Committee, which was the result of debates about the failed uprising and the directions of the activities in exile. As possibly the first organisation in Europe to have the adjective ‘democratic’ in its name, the Society exerted a strong influence on Polish political life in the 19th century. In fact, it was the longest-existing organisation in exile, as its dissolution took place only in 1862. Moreover, the Society proved its organisational effectiveness: it had a clearly exposited political program and agenda, it established a network of would-be conspirators within the Polish lands, and was able to run several journals, amongst which Demokrata Polski (Polish Democrat) occupied a central place. The Society was also influential in the number of its rank-and-file members: at the peak of its activity, this organisation had approximately 2,500 members. For these reasons, certain historians (e.g., Sławomir Kalembka) have contended that the Society was in fact the very first modern Polish political party.[4] Thanks to these democrats’ close engagement with the ideas of the day, the asymmetrical pair of counter-concepts ‘individualism-socialism’ became transferred into Polish political discourse. As usual, however, transfer is not solely a process of passive transmission of a certain idea from its domestic context into the new absorbing one. Rather, it is always a process of creative adaptation that does not take place without frictions. From this angle, conceptual transfer arrives rather as multi-layered mediation involving numerous creative actors (authors, translators, publishing houses, funders, readers, and the like). This was exactly the case with the Polish democrats-in-exile, as they adapted the pair of ‘individualism-socialism’ to their own particular goals. Primarily, it came in handy when they tried to present themselves not as dangerous radicals, but rather as representatives of a golden mean between two extremes. In this way, the democrats made an effort to position themselves between the two political wings that existed within the Polish political milieu in exile: socialism represented by certain groups situated on the left of the Polish Democratic Society (such as the Commons of the Polish People, Gromady Ludu Polskiego), and individualism, associated with liberal-aristocratic conceptions, was to create negative alignments with the political milieu led by prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski (1770–1861). Over the course of time, the Polish idea of democracy broadened its meaning. In the early 1830s, when the Polish Democratic Society was formed, democracy as a concept was associated solely with certain forms of organising political power. As the debates unfolded, however, it received new layers of meaning, saturated by new transferred concepts (derived mostly from the French republicanism and early socialism). First of all, in the 1840s democracy became a definite political movement, opposed to aristocracy, and, consequently, one type of possible political identification. What is more, democracy during that decade was also associated with a specific vision of society: its realisation was to be dependent on the transformation of the Polish socio-political realities that existed at that time. Last but not least, ‘democracy’ likewise meant supporting a certain historical viewpoint, as it encompassed a precise vision of the past as well. These conceptual changes finally set the scene for the emergence of the concept of ‘democratism’, which became a label for a fully-fledged ideology that in the Polish context encompassed several ‘spaces of experience’—to use the term Reinhart Koselleck deploys to depict our experiences not as structures depending on chronological time, but rather as interrelated, malleable, and contingent paths. Indeed, ‘democratism’ was a future-oriented concept, defined as a golden mean between socialism and individualism (or egoism). ‘Democratism’ was presented as a specific adaptation of the pure teachings of Jesus, and thus became the watchword of the Polish people’s liberation. Interestingly, however, despite its clear universalistic orientation, ‘democratism’ was further described by the Polish democrats as a native Slavic concept. In spite of their claims, we instead suggest that the notion of ‘democratism’ itself was likely first coined in German political debates (in the early 1840s), and potentially permeated into Polish political discourse from there.[5] This is also indicated by the fact that one of the first Polish democrats who began to use the concept of democratism was Jan Kanty Podolecki (1800–1855), who before 1848 lived in Galicia, so in the part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth controlled by Austria. Podolecki found himself in exile after 1848, and became a member of the central section of the Polish Democratic Society that was formed in London at the turn of the 1840s and 1850s. Seen from this angle, the concept of ‘democratism’ encapsulates experiences related to several different political and social contexts. The concept of ‘democratism’, however, turned out to be relatively short-lived. In the 1850s and 1860s, when the Polish Democratic Society found itself in organisational crisis, it began to lose popularity and importance. In fact, later on, the meaning of the concept of democracy (rather than ‘democratism’) in Polish political discourse became twisted once again, no longer signifying an ideology, but rather returning to its original meaning, i.e., referring mostly to the form of organisation of political power. The history of the concept thus acts as a microcosm, offering an insight into the process by which a political ideology is constructed and then later declines. Our method and revealed case exhibit an additional dimension of topicality, which lies not only in addressing these questions by tracing the international connections that pervade intellectual history, but likewise in shining a light onto the process of unfolding a new ideology and, subsequently, onto its disintegration. It may be particularly interesting for scholars working on contemporary history in a time of great ideological changes such as today, where numerous conceptions coined beyond the Western world are coming to the fore and constituting new ideological constellations. [1]Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of revolution: Europe 1789-1848 (London: Abacus, 1977). [2]Michael Freeden, Ideologies and political theory: a conceptual approach (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998). [3]Reinhart Koselleck, 'Einleitung', in: Reinhart Koselleck, Werner Conze, and Otto Brunner (eds.), Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. vol. 1 (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1972), XIII-XXVII. [4]Sławomie Kalembka, Towarzystwo Demokratyczne Polskie w latach 1832-1846 (Toruń: TNT; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1966), 261. [5]Jörn Leonhard, ‘Another “Sonderweg”? The Historical Semantics of “Democracy” in Germany’, in: Jussi Kurunmäki, Jeppe Nevers, and Henk te Velde (Eds.), Democracy in Modern Europe: A Conceptual History (New York; Oxford: Berghahn Books: 2018), 74–75. by Katrine Fangen

Over the past two decades, negative images of Muslims and Islam have become widespread throughout Europe and North America. Many of the images represent Islam (and particularly male Muslims) as a threat, as can be seen in the portrayal of Muslims as potential terrorists, as rapefugees (rapist refugees), or as patriarchal and misogynistic. In addition, worries are expressed about Muslims becoming ‘too many’ in number, leading to the gradual decline of the national population (defined as non-Muslim). Although some of these images have a long history in Europe, and can be traced back to colonialism and Orientalism,[1] research has identified a sharp increase in representations of Islam as a threat after 9/11, when ‘virtually all parties and formations on the radical right made the confrontation with Islam a central political issue’.[2] Within more mainstream political parties, too, there have been calls for the acculturation of Muslims to ‘our way of life’.[3] The ‘war on terror’ itself has been said to have contributed to the derogatory portrayal of Muslims.[4] Other critical events during the past two decades have also contributed to the threat-image of Islam, including Turkey’s EU application, which led to a ‘Europe versus Islam’ discourse,[5] and the civil war in Syria, which triggered discussion on the securitisation of borders both in the aftermath of the war and during the preceding ‘refugee crisis’.[6]