by Daniel Davison-Vecchione

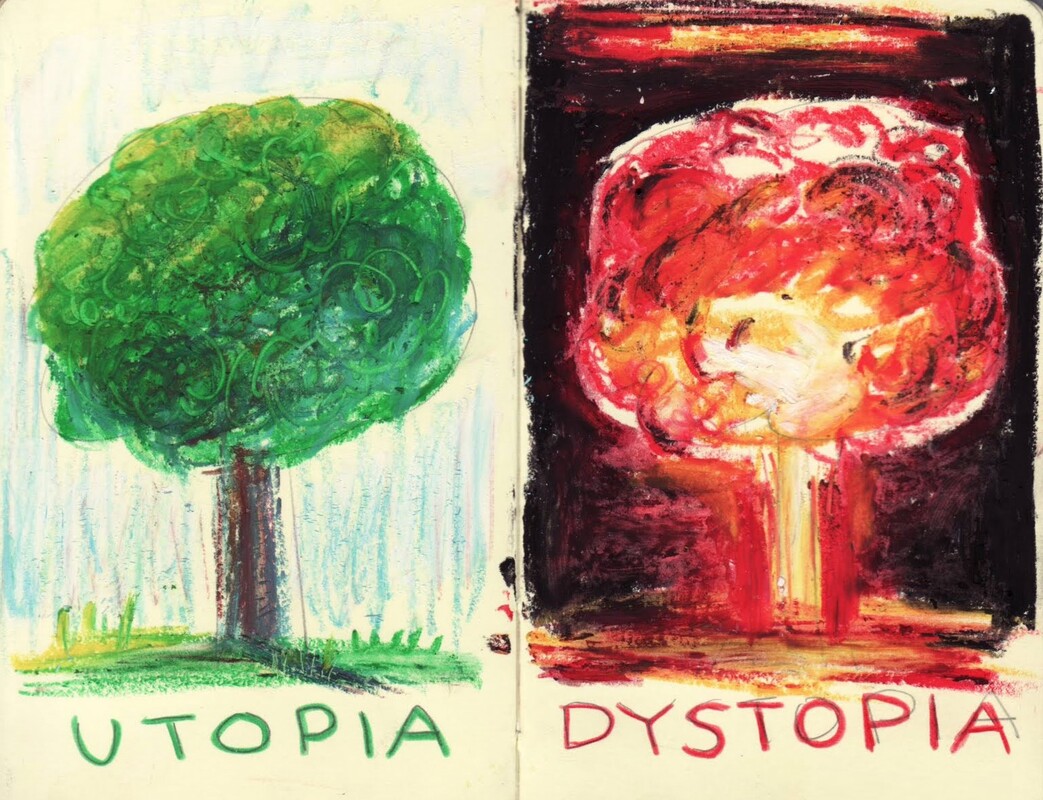

Social theorists are increasingly showing interest in the speculative—in the application of the imagination to the future. This hearkens back to H. G. Wells’ view that “the creation of Utopias—and their exhaustive criticism—is the proper and distinctive method of sociology”.[1] Like Wells, recent sociological thinkers believe that the kind of imagination on display in speculative literature valuably contributes to understanding and thinking critically about society. Ruth Levitas explicitly advocates a utopian approach to sociology: a provisional, reflexive, and dialogic method for exploring alternative possible futures that she terms the Imaginary Reconstitution of Society.[2] Similarly, Matt Dawson points to how social theorists like Émile Durkheim have long used the tools of sociology to critique and offer alternative visions of society.[3]

As these examples illustrate, this renewed social-theoretical interest in the speculative tends much more towards utopia than dystopia.[4] Unfortunately, this has meant an almost complete neglect of how dystopia can contribute to understanding and thinking critically about society. This neglect partly stems from how under-theorised dystopia is compared to utopia. Here I make the case for considering dystopia and social theory alongside each other.[5] In short, doing so helps illuminate (i) the kind of theorising about society that dystopian authors implicitly engage in and (ii) the kind of imagination implicitly at work in many classic texts of social theory. The characteristics and politics of dystopia A simple, initial definition of a dystopia might be an imaginative portrayal of a (very) bad place, as opposed to a utopia, which is an imaginative portrayal of a (very) good place. In Kingsley Amis’ oft-quoted words, dystopias draw “new maps of hell”.[6] Many leading theorists, including Krishan Kumar and Fredric Jameson, tend to conflate dystopia with anti-utopia.[7] It is true that numerous dystopias, such as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940), concern the horrifying consequences of attempted utopian schemes. However, not all dystopias are straightforwardly classifiable as anti-utopias. Take Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). The leaders of the patriarchal, theocratic Republic of Gilead present their regime as a utopia, which one might consider a kind of counter-utopia to what they see as the naïve and materialistic ideals of contemporary America, and at least some of these leaders sincerely believe in the set of values that the regime realises in part. One might therefore conclude that the novel is a warning that utopian thinking inevitably leads to and justifies oppressive practices. However, I would argue that The Handmaid’s Tale is not a critique of utopia as such, but rather of how actors with vested interests frame the actualisation of their ideologies as the attainment of utopia to discourage critical thinking. This reading is supported by how, for many members of Gilead’s ruling elite, the presentation of their society as a utopia is little more than self-serving rhetoric they use to brainwash the women they subjugate. Other dystopian works contain anti-utopian elements but subordinate these to the exploration of other themes. For instance, a subplot of Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan (2017) concerns a celebrity-turned-dictator’s dream of a technologically “improved” humanity, but resource wars, global warming, and other factors had already made the novel’s setting decidedly dystopian before this utopian scheme arose. Finally, there are major examples of dystopian literature, such as Octavia Butler’s Parable series (1993–1998), that depart from the anti-utopian template altogether. Tom Moylan has begun to rectify the dystopia/anti-utopia conflation via the concept of the critical dystopia. In his words, critical-dystopian texts “linger in the terrors of the present even as they exemplify what is needed to transform it”.[8] Put simply, critical dystopias are dystopias that retain a utopian impulse. Although this helps us understand many significant dystopian works, such as Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Gold Coast (1988) and Marge Piercey’s He, She and It (1991), the idea of the critical dystopia runs into its own problems. By labelling as “critical” only those dystopias that retain a utopian impulse, one makes it seem as if dystopia does not help us to understand and evaluate society in its own right—dystopia’s critical import becomes, so to speak, parasitic on utopia. To illustrate how this sells dystopia short, consider the extrapolative dystopia; that is, the kind of dystopia that identifies a current trend or process in society and then imaginatively extrapolates “to some conceivable, though not inevitable, future state of affairs”.[9] Many of Atwood’s novels fall into this subcategory. In her own words, The Year of the Flood (2009) is “fiction, but the general tendencies and many of the details in it are alarmingly close to fact”, and MaddAddam (2013) “does not include any technologies or biobeings that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory”.[10] These texts, which together with Oryx & Crake (2003) form Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, consider possible, wide-reaching changes that are rooted in present-day social and technological developments and raise pressing questions as to environmental degradation, reproduction and fertility, and the boundaries of humanity. Similarly, Butler constructs the dystopian future in her Parable series by extrapolating from familiar tendencies within American society, including racism, neoliberal capitalism, and religious fundamentalism. My point is not simply that these extrapolative dystopias are cautionary tales. It is that one cannot reduce their critical effect to either the negation or the retention of a utopian impulse. They identify certain empirically observable tendencies that have serious socio-political implications in the present and are liable to worsen over time. As such, they are critiques of present-day social phenomena and (more or less) plausible projections of how a given society might develop. The implicit message is that we can avoid the bad future in question through intervention in the present. This is how dystopia can translate into real-world political action. Taking perhaps the most famous twentieth century dystopia, in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) George Orwell was not simply satirising Stalin’s USSR or Hitler’s Germany. He was also considering the nature and prospects of the worldwide developments he associated with totalitarianism, including centralised but undemocratic economies that establish caste systems, “emotional nihilism”, and a total skepticism towards objective truth “because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuehrer”.[11] In Orwell’s words, “That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible”.[12] In the last couple of decades, dystopian texts have frequently sought to make similar points about global warming, digital surveillance, and the “new authoritarianisms”. One can certainly argue that taking dystopia too seriously as a means of critically understanding society risks sliding into a catastrophist outlook that emphasises averting worse outcomes rather than producing better ones. However, one should bear in mind that dystopia does not (and should not) aim to provide a comprehensive political program; rather, it provides a speculative frame one can use to consider current developments, thereby yielding intellectual resources for envisaging positive alternatives. The social theory in dystopia and the dystopia in social theory This brings us to the more direct affinities between dystopia and social theory. To begin with, protagonists in dystopian texts like Orwell’s Winston Smith, Atwood’s Offred, and Butler’s Lauren Olamina tend to be much more reflective and three-dimensional than their classical utopian counterparts. This is because, unlike the “tourist” style of narration common to utopias, dystopias tend to be narrated from the perspective of an inhabitant of the imagined society; someone whose subjectivity has been shaped by that society’s historical conditions, structural arrangements, and forms of life.[13] As Sean Seeger and I have argued, this makes dystopia a potent exercise in what the American sociologist C. Wright Mills termed “the sociological imagination”; that is, the quality of mind that “enables us to grasp [social] history and [personal] biography and the relations between the two”, thereby allowing us to see the intersection between “the personal troubles of milieu” and “the public issues of social structure”.[14] Since dystopian world-building takes seriously (i) how a future society might historically arise from existing, empirically observable tendencies, (ii) how that society might “hang together” in terms of its political, cultural, and economic arrangements, and (iii) how these historical and structural contexts might shape the inner lives and personal experiences of that society’s inhabitants, one can say that such world-building implicitly engages in social theorising. Conversely, the empirically observable tendencies from which dystopias commonly extrapolate, and the ethical, political, and anthropological-characterological questions dystopias frequently pose, are central to many classic texts of social theory. For instance, Max Weber saw his intellectual project as a cultural science concerned with “the fate of our times”.[15] He extrapolated from such related macrosocial tendencies as rationalisation and bureaucratisation to envisage modern humanity encased and constituted by a “shell as hard as steel” (“stahlhartes Gehäuse”) and feared that “no summer bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness”.[16] This would already place Weber’s social theory close to dystopia, but the resemblance becomes uncanny when one also considers Weber’s central interest in “the economic and social conditions of existence [Daseinsbendingungen]” that shape “the quality of human beings” and his related emphasis on the need to preserve human excellence and to avoid giving way to mere “satisfaction”.[17] This is a dystopian theme par excellence, as seen from such classics in the genre as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1951), which gives additional significance to the famous, Nietzsche-inspired moment at the end of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905). Here Weber wonders who might “live in that shell in the future”, including the ossified and self-important “last men”; those “specialists without spirit, hedonists without a heart” who “imagine they have attained a stage of humankind [Menschentum] never before reached”.[18] Like a good extrapolative-dystopian author, Weber provides a conceptually rich account of social phenomena by reflecting on what is currently happening and speculating about its further development and implications. It therefore seems that the dystopian imagination has always been at play within the sociological canon. While the extent of the overlap between dystopia and social theory is yet to be fully determined, much of this overlap no doubt stems from how central social subjectivity is to both endeavours. It is true that, in their representations of societies, dystopian authors as writers of fiction are not subject to the same demands of accuracy as social theorists. Nevertheless, the critical effect of much dystopian literature relies heavily on empirical connections with the world inhabited by the reader and, conversely, social theory often evaluates by speculating about the possible consequences of current tendencies. As such, one cannot consistently maintain a straightforward separation between the two enterprises. I am therefore confident that this nascent, interdisciplinary area of study will be productive and insightful for both social scientists and scholars of speculative literature. My thanks to Jade Hinchliffe, Sean Seeger, Sacha Marten, and Richard Elliott for their helpful comments on an early draft of this essay. [1] H. G. Wells, “The So-Called Science of Sociology,” Sociological Papers 3 (1907): 357–369, 167. [2] Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [3] Matt Dawson, Social Theory for Alternative Societies (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016). [4] Zygmunt Bauman is a partial exception. See Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity, 2000 [1989]), 137; Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity, 2000), 26, 53–64; Zygmunt Bauman, Retrotopia (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), 1–12. [5] This essay raises and builds on points Sean Seeger and I have made in our ongoing collaborative research on speculative literature and social theory. See Sean Seeger and Daniel Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” Thesis Eleven 155, no. 1 (2019): 45-63. [6] Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1960). [7] Krishan Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times (London: Blackwell, 1987), viii; Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future (London: Verso, 2005), 198. [8] Tom Moylan, Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia (New York: Routledge), 198-199. [9] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 55. [10] Quoted in Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 482. [11] Quoted in Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times, 292-93. [12] Ibid. [13] This is complicated by the “critical utopias” that arose in the 1960s and 70s, which emphasise subjects and political agency much more than their classical antecedents. [14] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 50; C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000 [1959]), 6, 8. [15] See, e.g., Lawrence A. Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage: Culture, Politics, and Modernity in the Thought of Max Weber (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1991); Wilhelm Hennis, Max Weber’s Central Question (Newbury: Threshold Press, 2000). [16] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trs. Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 121; Max Weber, “Politics as a Vocation,” in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, eds. H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005) 77-128, 128. “Iron cage” is Talcott Parsons’ mistranslation of “stahlhartes Gehäuse”. [17] Max Weber, “The National State and Economic Policy” (1895), quoted in Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage, 30. [18] Weber, Protestant Ethic, 121. Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed