by Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien

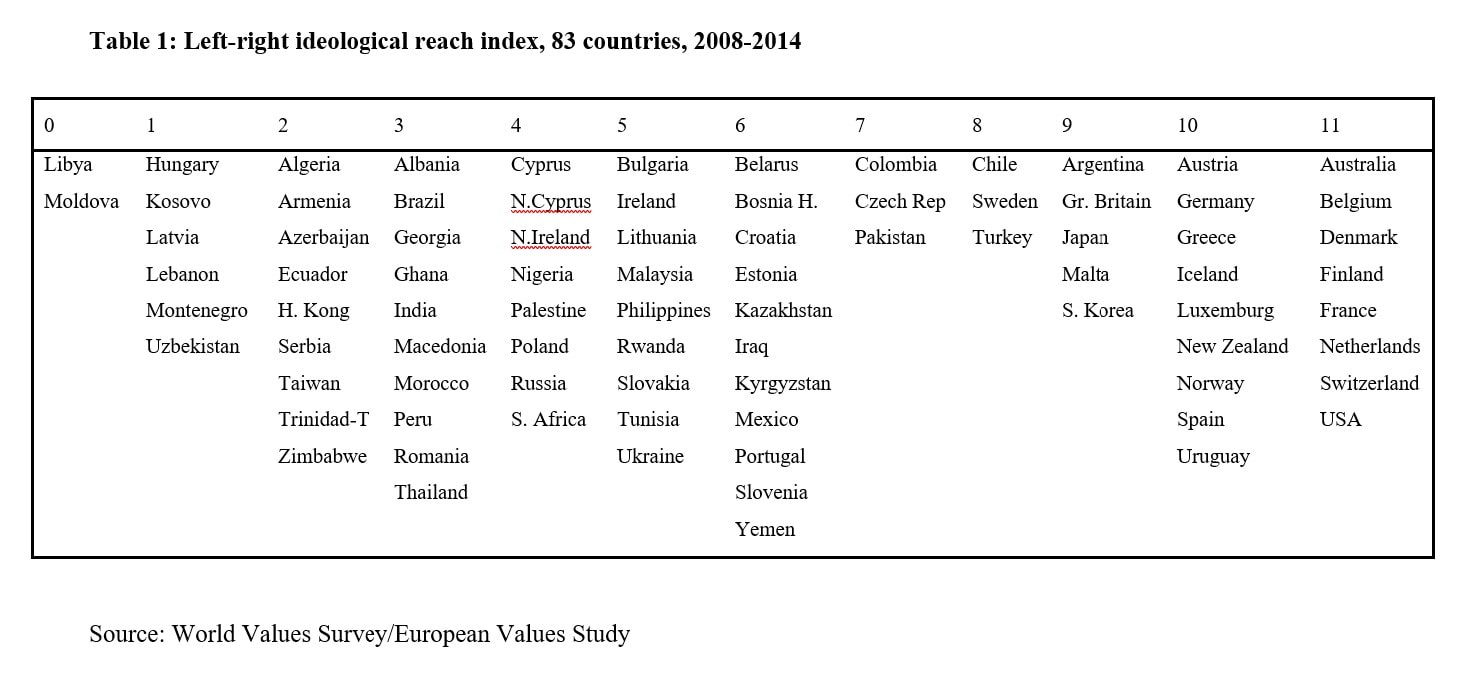

In recent years, several analysts have contended that the old cleavage between left and right has faded gradually, to become less central politically than it once was. The end of communism, the unchallenged victory of market capitalism, and the rise of neoliberalism narrowed the distance between parties of the left and of the right, and reduced the range of options available in political debates. Yet, although the left-right distinction may have become blunter as a cognitive instrument for politicians and voters, numerous studies show that it has not been replaced. In fact, no ideological cleavage is more encompassing and ubiquitous than the opposition between the left and the right.[1] When asked, most people across the world are able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, which basically divides those who support or oppose social change in the direction of greater equality. Ideological self-positioning also tends to be in line with the values and policy preferences associated with one of the two sides. The strength of this left-right schema, however, varies significantly among countries. In some cases, left-right positions correlate strongly with expected attitudes about equality, the state, the market, or social diversity; in others, they do not. We know little about the factors that make the left-right opposition more or less effective in structuring national debates. At best, existing studies suggest that left-right ideology is a more powerful constraint in Western democracies than elsewhere. To assess this question, we have taken the measure of cross-national variations in left-right ideology in 83 societies, and linked them to various factors, including economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy. Instead of focusing on individual determinants of ideology such as social class, gender or education, as scholars generally do, our analysis looks at country-level survey evidence and evaluates how, in each country, political debates are framed, or not framed, in left-right terms. The idea, along the lines suggested by Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, is to take the mass attitudes measured by large-N comparative survey projects as “stable attributes of given societies,” and as indicative of a country’s elites’ success in structuring politics along left-right dimensions. More specifically, we consider answers to twelve survey questions that capture the standard dimensions of the left-right political distinction. All answers were collected between 2008 and 2014 through the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS). The twelve questions include, for each society, one on individual left-right self-positioning, and eleven related to issues that have historically divided the two sides. The varying degree of ideological consistency in citizens’ responses then makes it possible to assess the architecture of a country's political debates and make cross-national comparisons. This approach to the workings of left-right ideology has two advantages. First, it moves the discussion of ideology beyond Western countries, and makes it possible to draw an extensive map of national ideological patterns. Second, and more importantly, because we use aggregate survey evidence, we can assess national-level causal mechanisms, and weigh, in particular, the respective influence of economic, social, and political factors on the constitution of the left-right cleavage. Our results indicate that the left-right opposition is unevenly effective in structuring national politics. Individual answers to questions about equality, personal responsibility, homosexuality, the army, churches, or major companies correlate with left-right self-positioning in more than half of the countries considered. But answers to questions about abortion, government ownership of industry, competition, trade unions, or environmental groups correlate with ideological self-positioning in only a third of the cases. In line with the expectations of Inglehart and Welzel, we also find that economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy are the best predictors of a structured left-right debate. Theorising left and right The construction of ideological identities is both a top-down and a bottom-up process, whereby people adopt political orientations defined by elites and institutions in line with their own personal predispositions. Psychologists have naturally paid more attention to the bottom-up, personal determinants of ideology, while political scientists have been more interested in the top-down, collective process. As a top-down process, the building of the left-right divide hinges on a country’s elites’ and institutions’ capacity to propose to voters what Paul Sniderman and John Bullock call a “menu of choices.” For these authors, political institutions—most notably parties—give consistency to the views of ordinary citizens, by providing coherent menus from which they can choose. As left-right self-positioning is strongly correlated with partisanship, we can hypothesise that a long-established, institutionalised party system contributes to structure ideological debates along left-right lines, compared to the more volatile politics of countries with fragile democracies. To evaluate if the “menu of choices” proposed by a country’s elites and parties and adopted by voters is organised along left and right lanes, we test whether divisions in a country’s public opinion appear consistent with individual left-right self-positioning. People on the left are likely to be more favourable to equality, state intervention, public ownership, and trade unions, and people on the right better disposed toward markets, individual incentives, competition, and major companies. The left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion and more supportive of environmental organisations, and the right more at ease with churches and the armed forces. In countries where the menu of choices is strongly structured by the left-right opposition, there should be significant relationships between individual left-right self-positioning and the expected attitudes on these questions; in countries with a less powerful left-right schema, these relationships should be weaker. Moreover, one should expect a connection between the structure of left-right discourse and the human development sequence identified by Inglehart and Welzel. Economic development, secularisation, and democratisation broaden the possibility, the willingness, and the rights of people to consider social alternatives. Economic development fosters the material capacity of a people to make choices, secularisation expands the moral frontiers of available choices, and democratic consolidation allows political parties and groups to define over time a menu of choices ordered around the usual left-right patterns. Left-right patterns should thus be associated with these three dimensions of human development. Methodology 83 societies have a complete set of WVS/EVS answers for the questions we select. The core question of interest concerns left-right self-positioning, and it is addressed by asking respondents to locate themselves on a 1 to 10 scale going from left to right. Although the rate of response varies significantly across countries, overall, about three-quarter of respondents proved able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, allowing for valid inferences about ideology. To verify whether this left-right positioning corresponds to consistent ideological stances, we correlate left-right positioning to responses on substantive political issues. Some of our eleven ideological questions refer to the core socio-economic components of the left-right cleavage (attitudes about equality, private or public ownership, the role of government, or competition), others concern cultural or social values (attitudes about homosexuality and abortion), and others tap respondents’ views about various organisations (churches, the armed forces, labor unions, major companies, and environmental organisations). We expect people on the left to be more favourable to equal incomes, public ownership of business or industry, and the government’s responsibility “to ensure that everyone is provided for,” and less likely to consider that “competition is good.” Respondents on the left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion, and more confident in labour unions and environmental organisations, but less so in the churches, the armed forces, and major companies. Using national responses to our eleven questions on substantive issues, we build a composite dependent variable, called left-right ideological reach. This variable measures the extent to which, in a given country, left-right self-positioning predicts the expected ideological stances on substantive political issues. If, in country A, the relationship between self-positioning and, say, attitudes about equality is significant (p < 0.05) and in the expected direction, we give a score of 1, and if not of 0. Adding results for eleven questions, a country’s score for left-right ideological reach can then range from 0, when self-positioning never correlates in the expected direction with a substantive left-right political division, to 11, when the expected relationships are present for all questions. To account for national differences in ideological reach, we use indicators for economic development, secularisation, and democratic experience, as well as a number of control variables, for cultural differences in particular. Results Left-right ideological reach varies significantly across countries, from 0 for Libya and Moldova to 11 for a number of Western countries, including France and the United States. As Table 1 shows, there are 27 countries with scores of 0 to 3, where left-right self-positioning hardly predicts respondents’ positions on traditional issues dividing the left and the right; 31 where left-right ideological reach is moderate, with scores of 4 to 7; and 25 where a person’s ideological self-positioning predicts her position on most issues, most of the time, with scores of 8 to 11. This is a new, multidimensional, and country-scale representation of left and right public attitudes across the world, and the idea of a relationship between left-right self-positioning and substantive political orientations appears validated, at least for nearly two thirds of our sample.

A cursory look at the data suggests, in line with the literature and with our theory, that left-right ideological reach is influenced by economic and democratic development. Countries with high scores in Table 1 are predominantly rich, established democracies; countries at the low end of the scale tend to be poorer, with authoritarian regimes or newer democracies. Indeed, economic development, measured by GDP per capita, is strongly correlated with ideological reach, and so are our indicators of secularisation and democracy. In multiple regressions, the three explanatory variables considered are significant, with democracy coming first. Control variables for cultural differences (religiosity and civilisations) are non-significant. These results are consistent with our interpretation of the left-right divide as a political construct that has global resonance but is clearly more structured in countries that have long experienced economic development, secularisation, and democratic politics. They also dispose of the seemingly common sense but misleading argument that would jump from a look at the cases in Table 1 to the conclusion that left and right are a Western specificity. Looking closely at the same table, one can see countries like Uruguay, Argentina, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Pakistan with scores of 7 or more, and countries like Hungary, Taiwan, and Brazil with low scores. Fostered by economic development and to some extent by secularisation, the left-right cleavage remains, first and foremost, a product of the enduring democratic conflict for control of the government. Not surprisingly, a host of comparative politics writings lend support to this conclusion, and suggests that the left-right divide is more structuring in countries with a strongly institutionalised party system. Conclusion The evidence from cross-national surveys is rather clear: around the world, most people are able and willing to locate themselves on a left-right scale and when they do, they tend to understand what this self-positioning implies. Their understanding, however, tends to be more comprehensive in countries that are more advanced economically, more secular, and more solidly democratic. As political parties compete for the popular vote, they construct an ideological pattern that makes sense for both elites and voters, and that gives structure to politics. When they fail to do so, or when democracy is non-existent, political discourse remains more haphazard, driven by context and personalities. To go beyond these conclusions, we would need to probe further the political mechanisms that contribute to the development of ideology. Looking systematically at the party system institutionalisation hypothesis, in particular, would seem promising. For now, however, we can be satisfied that the language of the left and the right seems to function as an imperfect but critical unifying element in global politics. [1] Russell J. Dalton, ‘Social Modernization and the End of Ideology Debate: Patterns of Ideological Polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7:1 (2006), pp. 1-22; John T. Jost, ‘The End of the End of Ideology’, American Psychologist, 61:7 (2006), pp. 651-670; Peter Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 206-222; Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien, Left and Right in Global Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); André Freire and Kats Kivistik, ‘Western and Non-Western Meanings of the Left-Right Divide across Four Continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18:2 (2013), pp. 171-199. Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed