by Rieke Trimçev, Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, and Friedemann Pestel

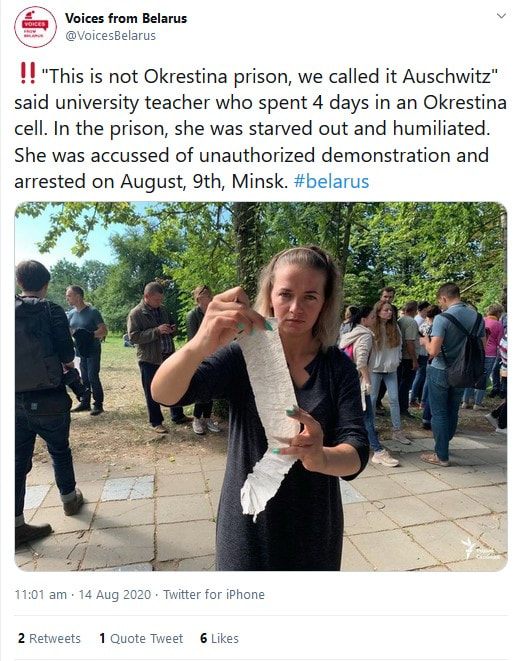

During the upheaval against Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus after the contested presidential election in August 2020, the idea of ‘Europe’ has often been invoked. These invocations might be surprising, given that Belarusians themselves have shunned explicit references to the EU and that EU flags were absent on the country’s streets. Instead, a rhetorical call to Europe has served to amplify demands for the support of Belarusian society and direct Europe’s attention to a country long-neglected by the international community. Lithuania’s former foreign secretary stated on Twitter: “The 21st century. The heart of Europe – Belarus. A criminal gang a.k.a. ‘Police Department of Fighting Organized Crime’ terrorizing Belarusians who have been peacefully demanding freedom and democracy for already 80 consecutive days. Shame!” Designating a particular region as “the heart of Europe” is a popular rhetorical device, acting as a way to call for attention. During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Margaret Thatcher used the metaphor to denounce the E.C.’s failure to prevent the mass killings in Bosnia: “this is happening in the heart of Europe […] It should be within Europe’s sphere of conscience.” The force of this phrasing defies geographical reality and lies in elevating specific values and principles as central to the idea of Europe. Europe’s political activity should live up to these values, simply to protect a vital part of its body. Through this formula, places like Belarus or Bosnia become part of a shared mental map, understood as a “spatialisation of meaning [that] dwells latently in the minds of individuals or groups of people.”[1] Another look at the rhetoric of the Belarusian protests indicates that shared representations of the past and the language of memory are particularly powerful tools in spatialising meaning and increasing the visibility of regional events for a transnational audience. All these tweets and pictures compare the Okrestina Detention Centre in Minsk, where many of the protesters were interned, to the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. Leaving aside the question of whether such comparisons are appropriate, their implication for protesters is clear: “The heart of Europe” is where Europe’s founding norm of “Never again!” is at risk.

The spatialised communication of normative arguments are at the core of our ongoing research project on the contested languages of European memory—“Europe’s Europes” if you will. It is informed by a larger qualitative study, in which we study public ideas of Europe through the prism of representations of the past and the language of memory. Examining press discourse in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2018, we have reconstructed several entrenched mental maps of Europe, which differ according to regional perspectives, ideological stances or historical trajectories. Some of these imaginaries—“Europe’s Europes”—complement each other, while others stand in open or implicit contradiction and provoke conflicts over the mental geography of Europe. To say that they are “entrenched” mental maps means that they are deeply rooted in everyday thought-behaviour and help to make sense of today’s political challenges. It is here that the language of memory, whose importance in forming shared senses of identity has long been noted, shows its ideological pertinence even beyond debates over memory politics strictly speaking.[2] Understanding these mental maps allows us to better seize discursive deadlocks, but also to identify missed encounters in debating in, over and with Europe. Islands of consensus The metaphor of the “heart of Europe” pictures Europe as a body whose different parts naturally work together to assure the functioning of a holistic “community of values”. While this metaphor might sound unsurprising, it turns out to be a concept that has a limited discursive reach, and is of limited agency when it comes to everyday political debates beyond grandiose speeches. In our study, we found that Europe is predominantly understood as a contested idea. Most of the deep-rooted mental maps spatialise this contestation through imaginary borders, both internal and external. Against the predominance of these fractured mental maps, ideas of Europe as a consensual community of values appear as “islands of consensus” of limited discursive reach. Between 2004 and 2018, one such “island of consensus” structured significant parts of the Italian press discourse, where Europe was pictured as a continent united through a canone occidentale, embracing Antiquity, Judaeo-Christian roots, Enlightenment, Liberalism, and other historical cornerstones with a positive connotation. This idea of a European canon also occurs in other national discourses but is more partisan. Especially in times of crisis, speaking from within a community of values has allowed for a clear yardstick of judgment. For example, the failure to set up a joint accommodation system for migrants in 2015, from the viewpoint of this mental map, appeared to betray European memory—a memory which had claimed a humanitarian impetus when boatpeople had fled from communism in the 1970s and 1980s: “On the issue of immigration, the Europe of the single currency and strengthened political governance seems less cohesive and less aware than Europe at the time of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War. The memory of the new Europeans and the new ruling classes seems indifferent to recent history.”[3] Yet, the moral self-confidence of dwellers of an island of consensus comes at some cost. From the perspective of an island of consensus, conflicts appear as a misunderstanding that could be solved by proper integration, inclusive of a European memory. However, this perspective remained largely confined to Italy and found little echo in other discursive spheres. Frictions between ‘East’ and ‘West’ A particularly prominent way of spatialising the meaning of Europe revolves around an East-West divide. While it is prominent both in ‘old Europe’ and those post-communist countries that joined the EU in 2004, it must be understood as the junction of two different, and in fact competing mental mappings. For France and Germany, ‘Eastern Europe’ largely represents a mnemonic terrain on which, after 1945, the communist regimes froze the memories of World War 2 and the Holocaust, and which still today rejects communist rule as an external imposition on its societies. Hence, post-communist societies are expected to catch up with the successful travail de mémoire or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which are associated with Western European societies. The ‘West’ is pictured as a spring of impartial rules for facing the past, rules that might in principle flow into the Eastern periphery to resuscitate withered memories. This even seems a precondition for the kind of dialogue suitable for bridging the often-decried East-West divide. From a Polish perspective however, the question of an East-West divide is not one of rules for remembering, but about determining a factual historical truth. “For Western elites it is difficult to accept that history for Eastern Europeans does not end with Hitler and the extermination of the Jews.”[4] It is the recognition of these truths and the national histories of suffering that is seen as the precondition of dialogue. From the perspective of this mental map, historical analogies can also serve to strengthen Poland’s position in the EU, for instance, when Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk likened Germany’s North Stream 2 pipeline to the Hitler-Stalin-Pact that had divided Poland and all of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. As the pipeline was “precisely such an agreement over the heads of others,”[5] it appeared impossible in the context of European integration in the 21st century. Periphery or boundary? Another entrenched way of mapping Europe proceeds not from its internal divisions, but from its external demarcation: Where does Europe end, or, how far does Europe reach? Again, in public discourse, asking this question serves to spatialise the strife over Europe’s core values. Over the 2000s and 2010s, the position of Turkey on Europe’s mental map has been the occasion to answer this question. And as for the East-West divide, what we observe is in fact a competition between two mental maps. From an affirmative perspective, Europe represents a clearly demarcated space, based either on conservative values such as its “Christian roots” or radical Enlightenment principles which are framed as universal and secular values. A test case for the latter was the recognition of the mass killing of 1,5 million Armenians as genocide—Europe had to end where this recognition was refused. French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy, at that point in favour of Turkish EU-membership, formulated the point very clearly: “amongst the criteria fixed by Brussels for the Turkish entry into the European Union, the most important condition is lacking: the recognition of the Armenian genocide. . . . During the genocide, Turkey attempted to amputate itself of its European part. This was a genocide, and a suicide.”[6] From the viewpoint of a competing mental map, Europe appeared rather as an open space, reflexive of its own history and its cultural, historical, and religious diversity. The political motives supporting the image of such an open Europe were highly heterogeneous. From a British viewpoint, Turkey’s EU membership ambitions represented a welcome occasion for renegotiating power relations within the EU and allowed the UK to articulate more utilitarian attitudes towards European integration. For Polish conservatives, Turkey presented an alternative to a model of integration marked by secularisation and unquestioned Westernisation. Instead of further secularising Turkey, they favoured a religious turn in European integration. Accordingly, the “conservative Muslim” went to the mosque on Fridays and “the conservative Pole” to church on Sundays.[7] Jeux d’échelles A last way of mapping Europe becomes evident in the question of how Europe links to the global context. This question is of particular importance in British discourse, where memories of the Empire project a national mnemonic order onto Europe. It is noteworthy indeed that other post-imperial countries such as France, Germany, Spain or Italy do not develop on this global component through a discussion of their past. Theresa May’s call for a “truly global Britain” which had the ambition “to reach beyond the borders of Europe” testifies to how, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, British spatial imaginaries were pitted against Europe, often referencing the UK’s more flexible economy as much as the historical grandeur of a Britain before European integration. Other countries explicitly reject such framings, but do not include perspectives from outside an alleged Europe either. The discourse on ‘European memory’ mostly relied on the ‘world’ to talk exclusively about Europe. Diverging ideas of Europe beyond conflict and consensus Mental maps of European memory stake claims of what constitutes Europe, who belongs to it and where the continent ends. In the mental maps sketched out here consensus is restricted to Sunday-best speeches and the Italian canone occidentale that exemplifies a form of model Europeanism. In contrast, the other spatial imaginations rely on the conflictive character of ‘European memory’ and demarcate the continent from an internal, external or global other. These findings provide a deeper understanding of European memory underpinning ideas of European integration and may also serve for further analysis of conflicts over the idea of Europe itself. In our future research, we will inquire into the diachronic shifts of these mental maps: they reveal the entangled relation between European integration and disintegration as scenarios for a future Europe. [1] Norbert Götz and Janne Holmén, ‘Introduction to the theme issue: “Mental maps: geographical and historical perspectives”’, Journal of Cultural Geography 35(2) (2018), 157. [2] Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, Daniela Mehler, Friedemann Pestel, and Rieke Trimçev, Europäische Erinnerung als verflochtene Erinnerung – Vielstimmige und vielschichtige Vergangenheitsdeutungen jenseits der Nation (Formen der Erinnerung 55) (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht unipress), 2014. [3] ‘Sfide dopo il no di Londra’, Corriere della Sera, 18.05.2015. [4] ‘Stalinizm jak nazizm’, Rzeczpospolita, 23.02.2008. [5] https://emerging-europe.com/news/polish-minister-compares-nord-stream-2-with-molotov-ribbentrop-pact/ [6] ‘Ma non si può parlare di adesione se non si scioglie il nodo del passato’, Corriere della Sera, 23.1.2007. [7] ‘Masowa imigracja to masowe problemy’, Rzeczpospolita, 25.07.2015. Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed