|

30/5/2022 Culture and nationalism: Rethinking social movements, community, and free speech in universitiesRead Now by Carlus Hudson

Although the study of social movements has shown that state institutions are not the only vehicles for societal change, the political forces which emanate from civil society and challenge state authority require theorisation. Near the end of his life, in 1967 Theodor Adorno conceptualised the post-1945 far right as a potent movement with social and cultural attitudes spread widely in West German society and still capable of attracting mass political support.[1] Nazism’s defeat in 1945, the partitioning of Germany and the process and legacy of denazification kept the re-emergence of a similar threat at bay, but the ideology did not disappear. By rejecting a monocausal social-psychological explanation of post-war fascism, Adorno also rejects the pessimistic idea of it as something that people must accept as an inevitable part of living in modern and democratic societies.

Anti-fascists have the agency to change society for the better and they have used it for as long as fascism has existed. Fascist street movements in the UK were defeated in the 1930s and again in 1970s by anti-fascists who mobilised against them in larger numbers at counter-demonstrations. Students took anti-fascism into the National Union of Students (NUS) by voting for the ‘no platform’ policy at the April 1974 conference. The aim of the policy, which built on earlier anti-fascist praxis and has returned in different forms since then, is to deny spaces in student unions to the ideas espoused by fascists and racists, thereby making them less mainstream and limiting the size of the audience reachable by fascist and racist ideologues. By no platforming, students were able to use their unions instrumentally to counter the influence of the extreme right. They were driven by moral revulsion at fascism and racism, a near-universal positive commitment to democratic freedom in society, and in smaller numbers commitments to anti-fascism and anti-racism as social movements and to left-wing politics. The same tactics were later used against homophobic, sexist, and transphobic speakers. Evan Smith’s critically acclaimed study of ‘no platform’ historicises the tactic’s use in the contexts of anti-fascism in Britain and contemporary fear on the right, which he argues is unfounded, for free speech on campuses.[2] Three essential points can be made from Smith’s study about what ‘no platform’ is. Firstly, it is a political decision made against a particular person or group of people. Secondly, those decisions rely on the judgement of the validity of specific demands for restrictions on free speech. Thirdly, ‘no platform’ is a specific type of restriction on free speech that is set apart from the functionally synchronous restrictions put in place by national governments. Governments have legislated limitations on free speech and protections on citizens’ rights to express it in a variety of ways. Free speech is not immutable because political dissidents occupy a contradictory space that leaves them permanently open as targets of state repression and targets of co-optation in the repression of the other. Marxist and anarchist theorists of fascism before 1945 conceptualised it in similar terms to their analyses of states, societies and ideologies: historical formations driven by class interests.[3] As a researcher of student activism, I notice how little can be found in their perspectives about student unions compared to united and popular fronts, revolutionary unions, and vanguard parties. Students’ involvement in political activities and adherence to different ideologies is well-documented. It suggests that student unions affiliated to universities remained peripheral in the organising activities and theoretical interventions of the interwar left. Meanwhile, the growth of free speech as a talking point for the right is unexpected judging by the norm in European and North American history, because of the state repression and censorship that accompanied reaction to political revolutions from the seventeenth to the late twentieth century.[4] While there is no reason to imagine this as any different from state repression outside of European and North American contexts, this chronology can be extended into the twenty-first century with consideration of the rise of new authoritarian governments in Poland, Hungary and Russia.[5] In the twentieth century the British government put limits on the freedom of speech to espouse extreme and hateful views using the Public Order Act 1936 and the Race Relations Acts passed in 1965, 1968 and 1975, but as Copsey and Ramamurthy have shown it has been anti-fascist and anti-racist movements rather than government legislation that has most to counter fascism and racism.[6] In the late 1960s and 1970s, when the National Front (UK) was at the height of its popularity posed a danger with the possibility of winning seats in local elections, it turned its hatred on Black and Asian immigrants under a thin veneer of populist opposition to immigration and criminality. It added Black and Asian people to Nazism’s older enemies—Jews, communists, the Romani, and LGBT people—while it kept its ideological core out of public view.[7] The brief and limited success of the National Front (UK) can be read patriotically as an aberration or an anomaly in a society that was utterly hostile and inhospitable to it. In this view, civil society would eventually have defeated the National Front without the help of anti-fascists or any compromise on free speech at universities. One problem with that interpretation is the racialisation of religious communities after the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the initiation of the War on Terror. Anti-Zionism, the broad-brush term for opposition to Israel, includes anything from criticism of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians on human rights grounds to opposition to Israel’s existence as a country. Left-wing anti-Zionism has received more attention in research about student activism than the anti-Zionism of the extreme right. NUS leaders opposed left-wing anti-Zionist uses of ‘no platform’ in the 1970s, when it was introduced to student unions.[8] After the September 11 attacks, anti-Zionism drew renewed criticism but with greater emphasis on Islamism. Pierre-Andre Taguieff explained the growth of a new type of European anti-Semitism in those terms.[9] In the popular press, a debate about Islamism spilled over into Islamophobic racism. For example, the printing in Charlie Hebdo and Jyllands-Posten of the Mohammed cartoons were acts of mainstreaming Islamophobia in France and Denmark that supported moral panic about Islam. The attack in France on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 had a chilling effect on free speech by contributing to a political climate where it became impossible for ‘those who felt unfairly targeted’ to respond and be heard.[10] Understanding the problem of Muslims being shut out of debates about them, and of being transformed into a debateable question in the first place, requires a consideration of counter-terrorism measures that have marginalised Muslims. In England and Wales, the regulation of charities and the government’s Prevent duty which covers the whole of the UK have added such pressures to the free speech of Muslim students and workers at universities.[11] The positioning of the presence of Muslims in majority White and Christian countries by non-Muslims as a question of cultural compatibility instead of Islamophobia as a racism morally equivalent to anti-Semitism makes it harder for multiculturalism to function there. That said, explanations of the racialisation of religious minorities are incoherent without analysing race. The number of examples that could be given to prove why restrictions on freedom of speech are too harsh in some instances but not harsh enough in others are practically without limit. Anti-fascists who also consider themselves to be communists or anarchists support the administration of justice in ways that are radically different from those in our own societies but which are nonetheless constructed on the same principles that adherents of liberal democracy follow, including freedom of speech. The same statement descends into nakedly racist prejudice when it is used to refer to racialised religious communities. Free speech is at the centre of a cultural conflict. The first two decades of the twenty-first century saw a world economic crisis and the growth of populism and authoritarianism on the right, which according to Francis Fukuyama capitalised on the need for social recognition felt by resentful supporters. As economic inequality grew, identity politics showed an alternative way for people to articulate difference.[12] Identity politics itself changed little through these processes. For example, a prevailing idea among American conservatives is that universities and colleges, like other levels of the education system and other sectors of civil society, are dominated by a left that threats freedom of speech. Dennis Prager sets the stage for a battle for liberal opinion between the left and, he argues, the centre’s natural allies on the conservative right.[13] His views about universities should not be decontextualised from his commentary on religion. In his book written with Joseph Telushkin, Prager explains anti-Semitism using a history of it and an engagement with Jewish identity. They acknowledge the influence of Taguieff’s research on their taking anti-Semitism more seriously as a tangible threat to Jews. Opposing Anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, which they barely distinguish, is a key part of their argument.[14] From another perspective, in his defence of classical liberalism, Fukuyama dedicates a chapter to discussing the global challenges in the twenty-first century to the principle of protecting freedom of speech. One argument he makes is that critical theory and identity politics, when they appear together in the contexts of free speech in higher education and the arts, mistakenly give too much importance to language as an interpersonal mode of political power and structural violence instead of the main targets of leftist critique: the coercive function of institutions and physical violence, capitalism and the state. With universities engaging with a wider definition of what constitutes harm than they have in the past, the parameters for unacceptable speech have widened too.[15] Free speech is no less a political issue today, by which I mean it is a term that people use to express their ideological attachments and experiences of real socio-economic conditions, than it has been in the past. Different conclusions can be drawn from these points. One option is to join socialists and progressives in their fights for equality and social justice through a movement that simultaneously counters the hegemony of right-wing ideology. Another option is to join the right’s defence of freedom of speech on campuses against ‘woke’ students and academics, ‘safer spaces’ and ‘trigger warnings’. Far from simply being bugbears, they are central concepts of opposition for the right in their wider defence of what they value most in their idea of Western civilisation. A more analytical response would be to engage more critically with what identity politics is and engage with the probing questions of how social movements driven by identity politics affect the inclusiveness of societies. Religious, secular and post-secular nationalisms are relevant here because they have a greater determining role than economic interest on political beliefs constructed around identity. However, their influence on politics organised along a left-right axis has never been negligible and the claim that a purely economistic political ideology can exist is highly dubious. Understanding identity politics gives context to the right’s fear for freedom of speech. Another approach is to take the right’s claim at face value and begin to think of freedom of speech as a legislated guarantee for the conditions of voluntary social interaction, without which civil society becomes an impossibility. It would therefore be morally necessary to consider the figuration of the right’s semi-invented enemies. The presentation of these enemies is not necessarily a racist act of subjective violence, and this caveat demarcates a large section of the right from fascists and identifies them as fascism’s serious competitors. At the same time, the right delegitimises its opponents by tarring them as enemies of freedom of speech and therefore a step closer to fascism. What these examples show is how complex an issue freedom of speech at universities is. Freedom of speech must be defined in recognition of that complexity because we are at the greatest risk of losing this freedom when we express ourselves under assumptions that lead us to oversimplify and decontextualise it. [1] Theodor W. Adorno, Aspects of the New Right-Wing Extremism, trans. Wieland Hoban (Medford: Polity, 2020). [2] Evan Smith, No Platform: A History of Anti-Fascism, Universities and the Limits of Free Speech, (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2020). [3] Dave Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, new and updated edition (London: Pluto Press, 2020). [4] Dave Renton, No Free Speech for Fascists: Exploring ‘No Platform’ in History, Law and Politics (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021), 11-34. [5] Dave Renton, The New Authoritarians: Convergence on the Right (London: Pluto Press, 2019). [6] Nigel Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain, second edition (London; New York: Routledge, 2017), 56; Anandi Ramamurthy, Black Star: Britain’s Asian Youth Movements (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 25. [7] Dave Renton, Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League 1976-1982 (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2019), 14-36. [8] Dave Rich, The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism (London: Biteback Publishing, 2016). [9] Pierre-André Taguieff, Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2004). [10] Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter, Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020), 75-9. [11] Alison Scott-Baumann and Simon Perfect, Freedom of Speech in Universities: Islam, Charities and Counter-Terrorism (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021). [12] Francis Fukuyama, Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition (London: Profile Books, 2018). [13] Jordan B. Peterson, No Safe Spaces? | Prager and Carolla | The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast - S4: E44, YouTube, vol. S4: E44, The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHXxtyUVTGU. [14] Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin, Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism, the Most Accurate Predictor of Human Evil (New York: Touchstone, 2007). [15] Francis Fukuyama, Liberalism and Its Discontents (London: Profile Books, 2022). by Lenon Campos Maschette

Over the past few centuries, the concept of civil society has shifted a few times to the centre of political debate. The end of the 20th century witnessed one of these moments. From the 1980s, civil society resurfaced as a central political idea, an important conceptual tool to address all types of social and political problems as well as describe social formations. At the end of the last century, a general criticism of the state and its inability to solve key social problems and the search for a ‘post-statist’ politics were problems shared by several countries that allowed the civil society debate to spread globally.[1]

In Britain, ideologies of the right had an important role in this movement. From the 1980s, all the discussions around community and citizen participation have to be analysed, at least in part, within the context of how the nature and function of the state were being reshaped, especially through the changes proposed by right-wing intellectuals and politicians. This tendency is even more noticeable within the British Conservative Party. In one of the most important works on the British Conservative Party and civil society, E. H. H. Green argues that the Conservative Party’s state theory throughout the 20th century was more concerned with the effectiveness of civil society bodies than with the role of the state.[2] Therefore, it is a long tradition that was continued and reinforced by Thatcher’s leadership. As I argued in another work, the Thatcher government redefined the concept of citizenship and placed civil society at the centre of its model of citizenship.[3] In this new article, I want to compliment that and argue that civil society had vital importance in Thatcher’s project. From this perspective, the Thatcher government redefined the idea of civil society, regarded as the space par excellence for citizenship—at least in the way Thatcherism understood it. Thatcherism attributed to civil society and its institutions a central role in the socialisation of individuals and the transmission of traditional values. It was the place par excellence of individual moral development and, consequently, citizenship. Thatcherism and civil society The Conservative Party never abandoned the defence of civil associations as both important institutions to deliver public services and essential spaces for maintaining and transmitting shared values. Throughout the post-WW2 period, the Party continuously emphasised the importance of the diversity of voluntary associations, and as a response to the growing dissatisfaction with statutory welfare, support for more flexible, dynamic, and local voluntary provision became part of its 1979 manifesto. As already mentioned, civil society had virtually disappeared from the public debate and Thatcher herself rarely used the term ‘civil society’. However, the idea had a central role within Thatcherism. As the article will show, the Conservatives were constantly thinking about the intermediary structures between individuals and the state, and from these reflections we can try to comprehend how they saw these institutions, their roles, and their relationships. According to the Conservatives, civil society was being threatened by a social philosophy that had placed the state at the centre of social life to the detriment of communities. In fact, civil society had not disappeared, but was experiencing profound changes. In a more affluent and ‘post-materialistic’ society, individuals had turned their attention from first material needs to identities, fulfilment, and greater quality of life. Charities and religious associations had also changed their strategies and came close to the approach and methods of secular and modern voluntary associations, loosening their moralistic and evangelical language and adopting a more political and socially concerned discourse. These are important transformations that are the basis of how the Thatcher government linked the politicisation of these institutions with the demise of civil society. Thatcher always made clear that voluntary associations and civil institutions were central to her ‘revolutionary’ project. The Conservatives under Thatcher regarded the civil institutions as the best means to reach more vulnerable people and the perfect space for participation and self-expression.[4] The neighbourhood, this smallest social ‘unit,’ was more personal and effective than larger and more bureaucratic bodies. Furthermore, civil society empowered individuals by giving them the opportunity to participate in local communities and make a difference. It is noteworthy that Thatcher’s individualism was not synonymous with an atomised and isolated individual. Thatcher did not have a libertarian view about the individuals. As she argued to the Greater Young Conservatives group, ‘there is not and cannot possibly be any hard and fast antithesis between self-interest and care for others, for man is a social creature … brought up in mutual dependence.’[5] According to her, there was no conflict between her ‘individualism and social responsibility,’[6] as individuals and community were connected and ‘personal efforts’ would ‘enhance the community’, not ‘undermine’ it.[7] She believed in a community of free and responsible individuals, ‘held together by mutual dependence … [and] common customs.’[8] Working in the local and familiar, within civil associations and voluntary bodies, individuals, in seeking their own purposes and goals, would also achieve common objectives, discharge their obligations to the community and serve their fellows and God.[9] And here is the key role of civil and voluntary bodies. They were responsible for guaranteeing traditional standards and transmitting common customs. By participating in these associations, individuals would achieve their own interests but also feel important, share values, strengthen social ties, and create a distinctive identity. Thatcherites believed that voluntary associations, charities, and civil institutions had a central position in the rebirth of civic society. These conceptions partly resonated with a conservative tradition that recognised the intermediated structures as institutions responsible for balancing freedom and order. For conservatives, civil institutions and associations have always played a central role within civil society as institutions responsible for socialising and moralising individuals. From the Thatcherite perspective, these ‘little platoons’—a term formulated by Edmund Burke, and used by conservatives such as Douglas Hurd, Brian Griffiths,[10] and Thatcher herself to qualify local associations and institutions—provided people a space to develop a sense of community, civic responsibility, and identity. Therefore, Thatcher and her entourage believed that civil society had many fundamental and intertwined roles: it empowered individuals through participation; it developed citizenship; it was a repository of traditions; it transmitted values and principles; it created an identity and social ties; and it was a place to discharge individuals’ obligations to their community and God. The state—not Thatcherism, nor indeed the market—isolated individuals by stepping into civil society spaces and breaking apart the intermediary institutions.[11] In expanding beyond its original attributions, the state had eclipsed civil associations and institutions. Centralisation and politicisation were weakening ‘mediating structures,’ making people feel ‘powerless’ and depriving individuals of relieving themselves from ‘their isolation.’[12] It was also opening a space for a totalitarian state enterprise. While the state was creating an isolated, dependent, and passive citizenry, the new social movements were politicising every single civil society space, fostering divisiveness and resentment. The great issue here was politicisation. Civil and local spaces had been politicised. The local councils were promoting anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-homophobic agendas, local government and trade unions were encouraging riots and operating ‘to break, defy, and subvert the law’[13] and the Church was ‘failing the people of England.’[14] Neoconservatives[15] drew attention to both the intervention and politicisation from the state but also from social movements such as feminism. As shown earlier, civil society dynamics had changed and new and more politicised movements emerged. John Moore, a minister and another long-term member of Thatcher’s cabinet, complained that modern voluntary organisations changed their emphases from service groups to pressure groups.[16] That is the reason why Thatcher, in spite of increasing grants to the voluntary sector, carefully selected those associations with principles related to ‘self-help and enterprise,’ that encouraged ‘civic pride’ while also discouraging grants to institutions previously funded by left-wing councils.[17] The state and the new social movements had politicised and dismantled civil society spaces, especially the conservatives' two most important civil institutions: the family and the Church. Thatcherism placed the family at the centre of civil society. Along with the ‘surrounding community of friends and neighbours,’ the family was a key institution to ‘individual development.’[18] This perspective dialogued with a conservative idea that came directly from Burke and placed the family at the core of civil society. From a Burkean perspective, the family was an essential institution for civilisation as it had two fundamental roles: acting as the ‘bulwarks against tyranny’ and against the ‘perils of individualism.’[19] The family was important as the first space of socialisation and affection and, consequently, the first individual responsibility. Within the family, moral values were kept and transmitted through generations, preventing degeneration and dependence. Thatcher’s government identified the family as the ‘very nursery of civil virtue’[20] and created the Family Policy Group to rebuild family life and responsibility. The family also had a decisive role in checking the state authority. Along with neoconservatives, Thatcherites believed that the welfare state and ‘permissiveness’ had broken down the family and its core functions. From this perspective, the most important civil institution had been corrupted by the state and the new social movements. If Thatcherism dialogued with neoliberalism and its criticism of the state, it was also influenced by conservative ideas of civil society and neoconservative arguments against the new social movements and the welfare state. Despite some tensions, Thatcherism was successful in combining neoliberal and neoconservative ideas. The other main civil institution was the Church. Many of Thatcher’s political convictions were moral, rooted in puritan Christian values nurtured during her upbringing. Thatcher and many of her allies believed that Christianity was the foundation of British society and its values had to be widely shared. The churches were responsible for exercising ‘over [the] manners and morality of the people’[21] and were the most important social tool to moralise individuals. Only their leaders had the moral authority ‘to strengthen individual moral standards’[22] and the ‘shared beliefs’ that provide people with a moral framework to prevent freedom to became something destructive and negative.[23] Thus, the conservatives had the goal of depoliticising civil society. It should be a state- and political-free space. Thatcher’s active citizen was an apolitical one. The irony is that the Thatcher administration made these institutions even more dependent on state funding. Thatcherism was incapable of comprehending the new dynamics of civil institutions. The diverse small institutions, mainly composed of volunteer workers, had been replaced by larger, more bureaucratic and professionalised ones closely related to the state. If the state and, consequently, politicians could not moralise individuals—which, in part, explains the lack of a moral agenda in the period of Thatcher’s government, a fact so criticised by the more traditional right, since ‘values cannot be given by the state or politician,’[24] as she proclaimed in 1978—other civil society institutions not only could, but had a duty to promote certain values. The Thatcher government and communities From the mid-1980s, the Conservative Strategy Group advised the party to emphasise the idea of a ‘good neighbour’ as a very distinct conservative concept.[25] The Conservative Party turned its eyes to the issue of communities and several ministers started to work on policies related to neighbourliness. At the same time, Thatcher’s Policy Unit also started thinking of ways to rebuild ‘community infrastructure’ and its voluntary and non-profit organisations. The civil associations more and more were being seen by the government as an essential instrument in changing people’s views and beliefs.[26] As we have seen, it was compatible with the Thatcherite project. However, it was also a practical answer to rising social problems and an increasingly conservative perception, towards the end of the 1980s, that Thatcher’s administration failed to change individual beliefs and civil society actors, groups, and institutions. And then, we begin to note the tensions between Thatcherite ideas and their implications for the community. Thatcherites believed in a community that was first and foremost moral. The community was made up of many individuals brought up by mutual dependence and shared values and, as such, carrying duties prior to rights. That is why all these civic institutions were so important. They should restrain individual anti-social behaviour through the wisdom of shared ‘traditional social norms that went with them.’[27] The community should set standards and penalise irresponsible behaviour. A solid religious base was therefore so important to the moral civil society framework. And here Thatcher was always very straightforward that this religious basis was a Christian one. Despite preaching against state intervention, Thatcher was clear about the central role of compulsory religious education to teach children ‘the difference between right and wrong.’[28] In order to properly work, these communities and its civil institutions should have their authority and autonomy restored to maintain and promote their basic principles and moral framework. And that is the point here. The conservative ‘free’ communities only could be free if they followed a specific set of values and principles. During an interview in May 2001—among rising racial tensions that lead to serious racial disturbances over that year’s spring and summer—Thatcher argued that despite supporting a society comprised of different races and colours, she would never approve of a ‘multicultural society,’ as it could not observe ‘all the best principles and best values’ and would never ‘be united.’[29] Thatcher was preoccupied with immigration precisely because she believed that cultural issues could have negative long-term effects. As she said on another occasion, ‘people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.’[30] Different individuals would work together and keep themselves together only if they shared some basic principles and beliefs. Thatcher’s community was based on common tradition, not consent or contract. Conservatives believed that shared values were essential for social cohesion. That is why a multicultural society was so dangerous from her perspective. Moreover, there is also another implication here. Multiculturalism not only needed to be repulsed because it was regarded as divisive, but also because it presupposes that all cultures have equal value. It was not only about sharing the same values and principles, but also about sharing the right values and principles. And for the conservatives, the British and Christian traditions were the right ones. That is why Christian religious education should be compulsory for everybody, regardless of their ethnic and cultural background. In part, it explains the Thatcher administration’s long fight against local councils and authorities that supported multiculturalism and anti-racist movements. They were seen as a threat to cultural and traditional values as well as national sovereignty. In addition to responding many times with brutal police repression to the 1981 riots—which is in itself a strong state intervention—the government also released resources for urban regeneration and increased the budget of ‘ethnic projects’ in order to control these initiatives. The idea was to shape communities in a given way and direction and create tools for the community to police themselves. The government was seeking ways to change individual attitudes that, according to the Conservatives, were at the root of social problems in the inner cities. Rather than being the consequence of social problems, these attitudes, they argued, were caused by cultural and moral issues, especially in predominantly black communities.[31] In encouraging moderate black leaders, the government was trying to foster black communities that would behave as British middle-class neighbourhoods.[32] Thatcher’s government also tried to shape communities through business enterprises and market mechanisms. In the late 1980s, her government started a bold process of community refurbishment that aimed to revitalise what were regarded as deprived areas. The market was also seen as a part of civil society and a moralising space that encouraged good behaviour. Thatcher’s relationship with the family, the basis of civil society, was also problematic. The Conservatives had a very traditional conception of family. The family was constituted by a heterosexual married couple. If Thatcherites accused new social movements of imposing their worldview on the majority, Thatcher’s government tried to prescribe a ‘natural’ view of family that excluded any type of distinct formation. Furthermore, despite presiding over a decade that saw a rising expansion of women's participation in the workplace and education, Thatcher advanced an idea of community that was based on women's caring role within the family and the neighbourhood. Finally, the Church, regarded as the most important source of morality, was, at first, viewed as a natural ally, but soon would become a huge problem for her government. As with many established British institutions, according to the Conservatives, the Church had been captured by a progressive mood that had politicised many of its leaders and diverted the Church's role on morality. The Church was failing Britain since it had abdicated its primary role as a moral leader. It was also part of a broader attack on the British establishment. Thatcher would prefer to align her government with religious groups that performed a much more ‘valuable role’ than the established Church.[33] The tensions between the Thatcher government's ideas and policies—which blended neoliberal and neoconservative approaches—and its results in practice would lead to reactions on both left and right-wing sides. If Thatcher herself realised that her years in office had not encouraged communities’ growth, the New Labour and the post-Thatcher Conservative Party would invest in a robust communitarian discourse. Tony Blair's Party would use community rhetoric to emphasise differences from Thatcherism, whereas the rise of ideas that focused on civil society, such as Compassionate Conservatism, Civic Conservatism, and Big Society, would be a Conservative response to the Thatcher's 1980s. Conclusion Conventionally, conservatives have treated civil society as a vehicle to rebuild traditional values, a fortress against state power and homogenisation that involved the past, the present and the future generations. Thatcher believed that a true community would be close to the one where she spent her childhood. A small community, composed by a vibrant network of voluntary bodies free from state intervention, in which apolitical and responsible citizens would be able to discharge their religious and civic obligations through voluntary work. These obligations resulted from religious values and individuals' mutual physical and emotional dependence, which imposed responsibilities prior to their rights, derived from these duties rather than from an abstract natural contract. Therefore, the Thatcherite community was, above all, a moral community. Accordingly, it was based on a narrow set of values and principles that was based on conservative British and Christian traditions. In a complex contemporary world of multicultural societies, it is difficult not to see Thatcher's community model as exclusionary and authoritarian. Despite her conservative ideas about neighbourhoods, her government seems to have encouraged even more irresponsible behaviour and community fragmentation. Thatcher seems not to have been able to identify the problems that economic liberalisation policies and strong individualistic rhetoric could cause to the community. Here, the tensions between her neoliberal and neoconservative positions became clearer. As she recognised during an interview, ‘I cut taxes and I thought we would get a giving society and we haven’t.’[34] To conclude, it is interesting to note that the civil society debate emerged in the UK with and against Thatcherism. The argument based on the revitalisation of civil society was used by both left and right-wingers to criticise the Thatcher years.[35] New Labour’s emphasis on communities, post-Thatcher conservatism’s focus on civil society, the emergence of communitarianism and other strands of thought that placed civil society at the centre of their theories; despite their differences, all of them looked to the community as an answer for the 1980s and, at least in part, its emphasis on the free market and individualism. On the other hand, as I have tried to show, Thatcherism was already working on the theme of community and raised many of these issues during the years following her fall. The idea of civil society as the space par excellence of citizenship and collective activities, as the place to discharge individual obligations and as a site of a strong defence against arbitrary state power, were all themes advanced by Thatcherism that occupied a lasting space within the civil society debate. Thatcherism thus also influenced the debate from within, not only through the reaction against its results, but also directly promoting ideas and policies about civil society. [1] Jean Cohen and Andrew Arato, Civil Society and Political Theory (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1997), 71-72. [2] E.H.H. Green, Ideologies of Conservatism. Conservative Political Ideas in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 278. [3] Lenon Campos Maschette, 'Revisiting the concept of citizenship in Margaret Thatcher’s government: the individual, the state, and civil society', Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021). [4] Margaret Thatcher, Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture (‘Liberty and Limited Government 11 January 1996). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/108353. [5] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to Greater London Young Conservatives (Iain Macleod Memorial Lecture, ‘Dimensions of Conservatism’ 4 July 1977). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103411. [6] Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: Harper Collins, 1993), 627. [7] Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Party Conference, 14 October 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation document 107352: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107352. [8] Margaret Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (‘I BELIEVE – a speech on Christianity and politics’ 30 March 1978). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103522. [9] Thatcher, The Moral Basis of a Free Society. Op. Cit. [10] Douglas Hurd had several important roles during Thatcher’s administration, including Home Office. Brian Griffiths was the chief of her Policy Unit from the middle 1980s and one of her principal advisors. [11] Michael Alison, ‘The Feeding of the Billions’, in Michael Alison and David Edward (eds) Christianity & Conservatism. Are Christianity and conservatism compatible? (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990), 206-207; Brian Griffiths, ‘The Conservative Quadrilateral’, Alison and Edward, Christianity & Conservatism, 218; Robin Harris, Not for Turning (London: Corgi Books. 2013), 40. [12] Griffiths, Christianity & Conservatism, 224-234. [13] Margaret Thatcher. Speech to Conservative Party Conference 1985. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106145. [14] John Gummer, apud Martin Durham, ‘The Thatcher Government and “The Moral Right”’, Parliamentary Affair, 42 (1989), 64. [15] American neoconservatives such as Charles Murray, George Gilder, Lawrence Mead, Michael Novak, etc., worked on the social, cultural, and moral consequences of the welfare state and the ‘long’ 1960s. They were also much more active in writing on citizenship issues. These authors had a profound influence on Thatcher’s Conservative Party through the think tanks networks. Murray and Novak, for instance, even attended Annual Conservative Party conferences and visited Thatcher and other Conservative members’ Party. [16] Timothy Raison, Tories and the Welfare State. A history of Conservative Social Policy since the Second World War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990), 163. [17] Geoffrey Finlayson, Citizen, State and Social Welfare in Britain 1830 – 1990 (Oxford, 1994), 376. [18] Douglas Hurd, Memoirs (London: Abacus, 2003), 388. [19] Richard Boyd, ‘The Unsteady and Precarious Contribution of Individuals’: Edmund Burke's Defence of Civil Society’. The Review of Politics, 61 (1999), 485. [20] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to General Assembly to the Church of Scotland, 21 May 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107246. [21] Douglas Hurd, Tamworth Manifesto, 17 March 1988, London Review of Books: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v10/n06/douglas-hurd/douglas-hurds-tamworth-manifesto. [22] Douglas Hurd, article for Church Times, 8 September 1988. THCR /1/17/111B. Churchill Archives, Churchill College, Cambridge University. [23] Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (1978), Op. Cit. [24] Margaret Thatcher, apud Matthew Grimley. Thatcherism, Morality and Religion. In: Ben Jackson; Robert Saunders (Ed.). Making Thatcher’s Britain. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2012), 90. [25] Many meetings emphasised this issue throughout 1986. CRD 4/307/4-7. Conservative Party Archives, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University. [26] ‘Papers to end of July’, 18 June 1987. PREM 19/3494. National Archives, London. [27] Edmund Neill, ‘British Political Thought in the 1990s: Thatcherism, Citizenship, and Social Democracy’, Mitteilungsblatt des Instituts fur soziale Bewegungen, 28 (2002), 171. [28] Margaret Thatcher, ‘Speech to Finchley Inter-church luncheon club’, 17 November 1969. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/101704. [29] Margaret Thatcher, interview to the Daily Mail, 22 May 2001, apud Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher, Vol. III Herself Alone (London: Penguin Books, 2019), 825. [30] Margaret Thatcher, TV Interview for Granada World in Action ("rather swamped"), 27 January 1978. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103485. [31] Oliver Letwin blocked help for black youth after 1985 riots. The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/dec/30/oliver-letwin-blocked-help-for-black-youth-after-1985-riots. [32] Paul Gilroy apud Simon Peplow. Race and riots in Thatcher’s Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 213. [33] Grimley, Op. Cit., 92. [34] Thatcher’s interview to Frank Field, apud Eliza Filby. God & Mrs Thatcher. The battle for Britain’s soul (London: Biteback, 2015), 348. [35] Neill, Op. Cit., 181. by Jack Foster and Chamsy el-Ojeili

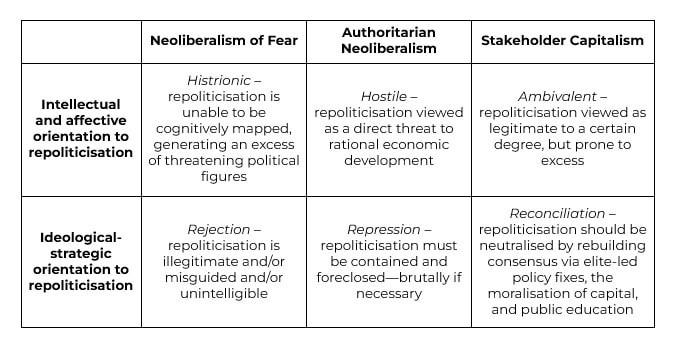

In September 2021, penning his last regular column for the Financial Times after 25 years of writing on global politics, Philip Stephens reflected on a bygone age. In the mid-1990s, an ‘age of optimism’, Stephens writes, ‘the world belonged to liberalism’. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the integration of China into the world economy, the realisation of the single market in Europe, the hegemony of the Third Way in the UK, and the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance presaged a century of ‘advancing democracy and a liberal economic order’. But today, following the financial crash of 2008 and its ongoing fallout, and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘policymakers grapple with a world shaped by an expected collision between the US and China, by a contest between democracy and authoritarianism and by the clash between globalisation and nationalism’.[1] Only five months later, the editors of the FT judged that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had definitively closed the ‘chapter of history opened by the fall of the Berlin Wall’; the sight of armoured columns advancing across the European mainland signals that a ‘new, darker, chapter has begun’.[2] At this juncture, with the all-consuming immediacy of the war in Ukraine, and the widespread appeal of framing the conflict in civilisational terms—Western liberal democracy facing down an archaic, authoritarian threat from the East—it is worth reflecting on some of the currents that flow beneath and give shape to the discourse of Western liberal elites today. In a previous essay, we argued that the leading public intellectuals and governance institutions of Western capitalism have struggled to effectively interpret and respond to the political and economic turmoil first unleashed by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008.[3] We traced out a crisis of intellectual and moral leadership among Western elites in the splintering of (neo)liberal discourse over the past decade-and-a-half—the splintering of what was, prior to the GFC, a relatively consensual ‘moment’ in elite discourse, in which cosmopolitan neoliberalism had reigned supreme. As has been widely argued, the financial crisis brought this period of confidence and self-congratulation to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Both the enduring economic malaise that followed the crash, and the crisis of political legitimacy that has unfolded in its wake, have shaken the intellectual and ideological certitude of Western liberals. All political ideologies experience ‘kaleidoscopic refraction, splintering, and recombination’, as they are adapted to historical circumstances and combined with elements of other worldviews to produce novel formations.[4] However, we argued that the post-GFC period has seen a particularly intense and marked splintering of (neo)liberal discourse into three distinctive but overlapping and intertwining strands or ‘moments’. First, a neoliberalism of fear,[5] which is animated by the invocation of various dystopian threats such as populism, protectionism, and totalitarianism, and which associates the contemporary period with the extremism and instability of the 1930s. Second, a punitive neoliberalism, which seeks to conserve and reinforce existing power relations and institutions of governance.[6] And third, a pragmatic and reconciliatory neo-Keynesianism, oriented above all to saving capitalism from itself. In this essay, we want to expand upon one aspect of this analysis. Specifically, we suggest here that one way in which we can distinguish between these three strands or ‘moments’ is as distinct responses to the repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management in the years following the GFC. Respectively, these responses can be summarised as rejection, repression, and reconciliation (see Table 1, below). Depoliticisation and repoliticisation In our previous essay, we argued that the 1990s and early 2000s were marked by the predominance of cosmopolitan neoliberalism as a successful project of intellectual and moral leadership, the moment of the ‘end of history’ and ‘happy globalisation’. In this period, we saw the radical diminution of economic and social alternatives to capitalism, the colonisation of ever more spheres of social life by the market, the transformation of common sense around the proper relationship between states and markets, the public and the private, equality and freedom, the community and the individual, and the institutionalisation of post-political management, or what William Davies has called ‘the disenchantment of politics by economics’.[7] Of this last, neoliberalism, as both a political ideology and a set of institutions, has always been oriented to the active depoliticisation and indeed dedemocratisation of ‘the economy’ and its management—what Quinn Slobodian calls the ‘encasement’ of the market from the threat of democracy.[8] In practice, this has been pursued in two primary ways. First, it has been accomplished via the legal and institutional insulation of ‘the economy’ from democratic contestation. Here, the delegation of critical public policy decisions to unelected, expert agencies such as central banks and the formulation of rules-based economic policy frameworks designed to narrow political discretion are emblematic. Second, this has been buttressed by ideological appeals to the constraints placed upon domestic economic sovereignty by globalisation and the necessity of technocratic expertise in government—strategies that lay at the heart of the Clinton administration in the US (‘It’s the economy, stupid!’) and the Third Way of Tony Blair in the UK. Economic management was to be left to Ivy League economists, central bankers, and the financial wizards of Wall Street and the City. The so-called ‘Great Moderation’—the period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that was characterised by low macroeconomic volatility and sustained, albeit unspectacular, growth in most advanced economies—lent credence to these ideas. The hubris of elites in this period should not be underestimated. As Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the influential Bank for International Settlements, put it to an audience of European financiers in 2019, ‘During the Great Moderation, economists believed they had finally unlocked the secrets of the economy. We had learnt all that was important to learn about macroeconomics’.[9] And in his ponderous account of how global capitalism might be saved from the triple-threat of financial instability, Covid-19, and climate change, former governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney recalls ‘how different things were’ prior to the credit crash—a period of ‘seemingly effortless prosperity’ in which ‘Borders were being erased’.[10] The GFC catalysed both an epistemological crisis in mainstream economics, and, after some delay, the rise of anti-establishment political forces on both the left and the right. The widespread failure to reflate economic development in the wake of the crisis and the punishing effects of austerity in the UK and the Eurozone, and at the state level in the US, only exacerbated the problem. Over the past decade-and-a-half, questions of economic development, of who gets what, and of who should be in charge, have come back on the table. How have Western elites responded? Rejection One dominant response to this repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management has been to invoke a host of dystopian figures—populism, nationalism, political extremism, protectionism, socialism, and totalitarianism—all of which are perceived as threats to the stability of the open-market order, to economic development, and to a thinly defined ‘liberal democracy’. This is the neoliberalism of fear Four years prior to the election of Donald Trump, the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks’ assessment was already grimly warning that the ‘seeds of dystopia’ were borne on the prevailing winds of ‘high levels of unemployment’, ‘heavily indebted governments’, and ‘a growing sense that wealth and power are becoming more entrenched in the hands of political and financial elites’ following the GFC.[11] In 2013, Eurozone technocrats were raising cautious notes around the ‘renationalisation of European politics’.[12] By 2015, Martin Wolf, long-time economics columnist for the FT, was informing his readers that ‘elites have failed and, as a result, elite-run politics are in trouble’.[13] This climate of fear reached fever-pitch in 2016, with the shocks delivered by the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, and again in January 2021, with mounting fears that President Biden’s inauguration would be blocked by a truculent Republican party. The utopian world of the long 1990s, in which globalisation was ‘tearing down barriers and building up networks between nations and individuals, between economies and cultures’, in the words of Bill Clinton, has thus disappeared precisely as ‘the economy’ and its management began to be repoliticised.[14] Two aspects of this often-histrionic neoliberalism of fear stand out. First, we see a striking inability to cognitively map the repoliticised terrain. Rather than serious attempts to map out why and in what ways repoliticisation is occurring, this strand or ‘moment’ is characterised by a reliance on a set of questionable historical analogies, above all the 1930s and the disasters of totalitarianism. Second, extraordinary weight is given over to these threats and fears, and there is a corresponding absence of serious attempts to construct a new ideological consensus. Instead, repoliticisation is countered in a language that is defensive, hectoring, and dismissive. For Wolf, populist forces have organised to ‘muster the inchoate anger of the disenchanted and the enraged who feel, understandably, that the system is rigged against ordinary people’.[15] In like fashion, former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, reflecting on his role in resolving the GFC, writes that in crises, ‘fear and anger and ignorance’ clouds the judgement of both the public and their representatives and impedes sensible policymaking; it is essential, in times of crisis, that decisions are left to coldly rational technicians.[16] Musing on the integration backlash in the EU, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, noted that while ‘protectionism is society’s natural response’ to unchecked market forces, it is crucial to ‘resist protectionist urges’, and this is the job of enlightened technocrats and politicians, who must hold back the populist forces threatening to roll back market integration.[17] In other words, while recognising that a rampaging globalisation has driven social and political unrest, within this neoliberalism of fear the masses are viewed as too capricious and ignorant to be trusted; the post-GFC malaise, while frightening and disorienting, will certainly not be solved by more democracy. Repression Closely related to, and overlapping with, this neoliberalism of fear is the second core strand or ‘moment’, that of a punitive and coercive neoliberalism. If the neoliberalism of fear can be understood as a dismissive overreaction to repoliticisation, this second strand represents a more direct and focused attempt to manage this new, more unstable, and more contested political economy. Fears of deglobalisation, of protectionism, of fiscal recklessness are also prominent in this line of argument; however, equally prominent are the necessary solutions: strengthening the rules-based global order, ongoing flexibilisation and integration of labour and product markets—particularly in the EU—and a harsh but altogether necessary process of fiscal consolidation. The problem of public debt has, of course, been one of the major battlegrounds here. Preaching the necessity of fiscal consolidation at the elite Jackson Hole conference in 2010, for example, Jean-Claude Trichet raised the cautionary tale of Japan, a country that ‘chose to live with debt’ in the 1980s and suffered a ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s as a result.[18] These concerns were widely echoed in the financial press and by international policy organisations; here, the threat of market discipline was also consistently evoked as justification for fiscal retrenchment and punishing austerity. As former IMF economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff infamously warned, prudent governments pay down public debt, because ‘market discipline can come without warning’.[19] Much has been made of the punitive, moralising, and post-hegemonic dimensions of this discourse.[20] However, it is worth bearing in mind that there are also genuine attempts to match the policy prescriptions associated with this more authoritarian and coercive neoliberalism—fiscal austerity, enhanced fiscal discipline and surveillance, structural adjustment, rules-based economic governance—with a positive vision of the political economy that these policies will deliver: economic growth, global economic stability, a route out of the post-GFC doldrums. Viewed in this way, the key ideological thrust here seems to be less that of punishment for punishment’s sake than it is of the deliberate repression and foreclosure of repoliticisation. Pace the classical neoliberal thinkers, the driving logic is that economic development and economic management are far too important to be left to democracy, which is altogether too fickle and too subject to capture by interest groups to be trusted. The upshot? Austerity, flexibilisation, the strengthening of the elusive rules-based global order: all this must be pushed through regardless of dissent. As with any ideological formation, shutting down alternative arguments is also important. As one speaker at the Economist’s 2013 ‘Bellwether Europe Summit’ put it, ‘the political challenge’ to structural adjustment ‘comes not from the process of adjustment itself. People can accept a period of hardship if necessary. It comes from the belief that there are better alternatives available that are being denied’.[21] In these ways, this second strand or ‘moment’ is directly hostile to the return of the political: less a hurried and defensive pulling-up of the drawbridge, as in the neoliberalism of fear, than a concerted counterattack. Reconciliation While this punitive and coercive neoliberalism seeks to repress repoliticisation by further insulating ‘the economy’ and its management from democratic interference, the third main strand of post-GFC (neo)liberal discourse responds to repoliticisation in a more measured way. In our previous writing on this issue, we referred to this strand or ‘moment’ as a pragmatic neo-Keynesianism, which promotes technocratic policy fixes aimed at lightly redistributing wealth and rebuilding the social contract. Over the past couple of years, we suggest, these more reconciliatory energies have coagulated into a relatively coherent ideological project, that of stakeholder capitalism.[22] Simultaneously, aided by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism of the 2010s has been discredited and has largely vanished from the pages of the financial press, the policy recommendations of the major international organisations, and the books and columns of Western public intellectuals. Thus, we use the term stakeholder capitalism to refer to the recent ideological shift in the Western policy establishment, among public intellectuals, and in business and high finance, that centres around the push for more ‘socially responsible’ corporations, for ‘green finance’, and for the re-moralisation of capitalism. By 2019, this shift was gathering momentum. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz implored readers of the New York Times to help build a ‘progressive capitalism’, ‘based on a new social contract between voters and elected officials, between workers and corporations, between rich and poor, and between those with jobs and those who are un- or underemployed’.[23] The FT launched its ‘New Agenda’, informing its readers that ‘Business must make a profit but should serve a purpose too’.[24] The American Business Roundtable, the crème de la crème of Fortune-500 CEOs, issued a new ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’, in which it revised its long-standing emphasis on promoting shareholder-value maximisation. Rather than narrowly focusing on returning profit to their shareholders, it now claims that corporations should ‘focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone—investors, employees, communities, suppliers, and customers’.[25] Similarly, the WEF launched its 50th-anniversary ‘Davos Manifesto’ on the purpose of a company, promoting the development of ‘shared value creation’, the incorporation of environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into company reporting and investor decision-making, and responsible ‘corporate global citizenship […] to improve the state of the world’.[26] And no lesser figure than Jaime Dimon, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, noted in his 2019 letter to shareholders that ‘building shareholder value can only be done in conjunction with taking care of employees, customers and communities. This is completely different from the commentary often expressed about the sweeping ills of naked capitalism and institutions only caring about shareholder value’.[27] Now, in early 2022, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, has announced that it will be launching a ‘Center for Stakeholder Capitalism’ in the near future.[28] The term ‘stakeholder management’ was originally coined by the business-management theorist Edward Freeman in the 1980s,[29] but the roots of this discourse go back to the dénouement of the first Gilded Age, where some business leaders began to promote the idea of the socially responsible corporation as a means of outflanking working-class discontent during the Great Depression.[30] The concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ then became popular in the 1990s, associated above all with the Third Way of New Labour.[31] Today, the discourse of stakeholder capitalism has been resurrected and updated, we suggest, in direct response to the repoliticisation of the economy and its management and the failure of authoritarian neoliberalism to provide a way out of the post-2008 quagmire. At the root of this rebooted version of stakeholder capitalism is an argument for the re-moralisation of capitalism in the interests of social cohesion and long-term sustainability. To be sure, there remains a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, consumer choice, and so on. But there is also a recognition of—or at least the payment of lip service to—the fact that a rampaging globalisation and widespread commodification has undermined social stability and cohesion. Thus, in contrast to the second strand or ‘moment’ of post-GFC (neo)liberalism, stakeholder capitalism seeks to deal with the repoliticisation of the economy and its management by establishing a more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. To establish a more inclusive capitalism means making some relatively significant shifts in economic policy. ‘[T]argeted policies that achieve fairer outcomes’ are the order of the day.[32] A more fiscally active state and investment in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D are all called for. So too is an expanded social-welfare safety net, primarily in the form of active labour-market policies. And above all, stakeholder capitalism is about tackling the green-energy transition, which presents, for boosters of a private-finance-led transition, ‘the greatest commercial opportunity of our time’.[33] This means ‘smart’ state intervention to steer and ‘derisk’ private investment.[34] Cultural reform, economic education, and democratic renewal are also viewed as important enabling features of this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. Here, policymakers must lead from the front, finding ways to better communicate with, and to educate, citizens and to foster consensus. In these respects, if the ‘moment’ of punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism was characterised by the repression of repoliticisation, then stakeholder capitalism seeks reconciliation. But while the legitimacy of democratic dissatisfaction is broadly recognised, and while there is a place for ‘more democracy’ in the discourse of stakeholder capitalism, this is democracy conceptualised not as the meaningful contestation of the distribution of power and resources, but as a relentless machine for building consensus. Opposing value systems and fundamental conflicts over the distribution of resources do not exist, only ‘stakeholder engagement’ oriented to revealing the ‘public interest’ or the preferences of ‘society’ at large. Exponents of stakeholder capitalism call for more education on how the economy works and emphasise the need to ‘listen’ more attentively to the citizenry. But the intention behind such endeavours is to develop or fortify consensus around already-existing institutions, or at best to tweak them at the margins. In these respects, there is an ambivalence running through this third—and perhaps now dominant—strand or ‘moment’: the mistrust of democracy, made explicit in the neoliberalism of fear and its authoritarian counterpart, is never completely out of the frame. Table 1: Rejection, repression, and reconciliation Horizons Despite its obvious limitations from the normative point of view of radical or even social democracy, the (re)emergent ideological formation of stakeholder capitalism does, we suggest, represent a relatively coherent attempt at rebuilding ideological consensus in Western societies. After years of intellectual and moral disorganisation, the rise to dominance of stakeholder capitalism among the policy establishment, high finance, some liberal intellectuals, and the financial press perhaps signals the reestablishment of intellectual and ideological discipline among elites. But it seems unlikely that this line of approach will bear fruit in the long run; the dysfunctions of the (neo)liberal world order—spiralling inequality and oligarchy, post-democratic withdrawal and outrage, resurgent nationalism, and anaemic, debt-dependent economic growth—run deep. More immediately, the war in Ukraine, and the unprecedented financial and economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers, threatens to once again reorder the ideological terrain and to intensify the shift away from globalisation. Perhaps the dominant response among (neo)liberal commentators thus far has been to frame the conflict as the first battle in a coming war for the preservation of liberal democracy: we are seeing the return of a more ‘muscular’ liberalism, reminiscent of the early years of the War on Terror.[35] Indeed, throughout modern history, war has served to restore liberalism’s ideological vigour; the conflict in Ukraine may yet prove to be a shot in the arm. [1] P. Stephens, ‘The west is the author of its own weakness’, Financial Times, 30 September 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9779fde6-edc6-4d4c-b532-fc0b9cad4ed9 [2] The Editorial Board, ‘Putin opens a dark new chapter in Europe’, Financial Times, 25 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a69cda07-2f63-4afe-aed1-cbcc51914105 [3] J. Foster and C. el-Ojeili, ‘Centrist Utopianism in Retreat: Ideological Fragmentation after the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 2021. [4][4] Q. Slobodian and D. Plehwe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian, and P. Mirowski (Eds), Nine Lives of Neoliberalism (London: Verso, 2020), p. 3. [5] N. Schiller, ‘A liberalism of fear’, Cultural Anthropology, 27 October 2016, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-liberalism-of-fear [6] W. Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’, New Left Review, 101 (2016), pp. 121-134. [7] W. Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty, and the Logic of Competition, revised edition (London: Sage, 2017). [8] Q. Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018). The reduction of essentially political problems to their economic dimension is a long-standing feature of liberalism as such and is therefore not an original aspect of neoliberalism; it is, however, particularly pronounced in the latter. [9] C. Borio, ‘Central banking in challenging times’, speech at the SUERF Annual Lecture, Milan, 2019. [10] M. Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 151. [11] World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2012 (Geneva: WEF, 2012), pp. 10, 19. [12] B. Cœuré, ‘The political dimension of European economic integration’, speech at the Ligue des droits de l’Homme, Paris, 2013. [13] M. Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What We Have Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 382. [14] William Clinton, ‘President Clinton’s Remarks to the World Economic Forum (2000)’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOq1tIOvSWg [15] Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks, p. 383. [16] T. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises (London: Random House, 2014), p. 209. [17] M. Draghi, ‘Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2017. [18] J-C. Trichet, ‘Central banking in uncertain times – conviction and responsibility’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2010. [19] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times, 28 January 2010. [20] See, for example, Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’. [21] J. Asmussen, ‘Saving the euro’, speech at the Economist's Bellwether Europe Summit, London, 2013. [22] J. Foster, ‘Mission-oriented capitalism’, Counterfutures 11 (2021), pp. 154-166. [23] J. Stiglitz, ‘Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron’, New York Times, 19 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [24] Financial Times, ‘FT sets the agenda with a new brand platform,’ Financial Times, 16 September 2019, https://aboutus.ft.com/press_release/ft-sets-the-agenda-with-new-brand-platform [25] Business Roundtable, ‘Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”’, 19 August 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [26] World Economic Forum, ‘Davos Manifesto 2020: The universal purpose of a company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’, 2 December 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/davos-manifesto-2020-the-universal-purpose-of-a-company-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/ [27] J. Dimon, ‘Annual Report 2018: Chairman and CEO letter to shareholders’, 4 April 2019, https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm?a=1 [28] L. Fink, ‘Larry Fink’s 2022 letter to CEOs: The power of capitalism’, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter [29] See E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984). [30] J. P. Leary, Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018), pp. 162-163. [31] For an early statement, see W. Hutton, The State We’re In (London: Random House, 1995). Freeman also wrote on the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ in the 1990s. It is notable that the drive to develop this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism is made in the absence of, and often disdain for, the key conditions that enabled Western social democracy to (briefly) thrive—namely, a more autarkic global political economy, mass political-party membership, high trade-union density, the ideological threat posed by Soviet communism, a more coherent and engaged public sphere, and stronger civil-society institutions. Further, exponents of stakeholder capitalism retain a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, and so on. For these reasons, we suggest that its closest ideological cousin is the Third Way. [32] B. Cœuré, ‘The consequences of protectionism’, speech at the 29th edition of the workshop ‘The Outlook for the Economy and Finance’, Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 2018. [33] Carney, Value(s), p. 339. [34] D. Gabor, ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52(3) (2021), pp. 429-459. [35] M. Wolf, ‘Putin has reignitied the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy’, Financial Times, 2 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed