by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

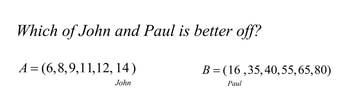

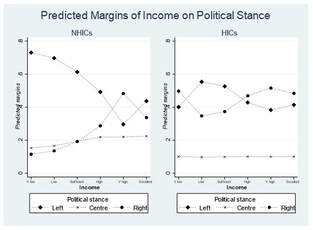

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

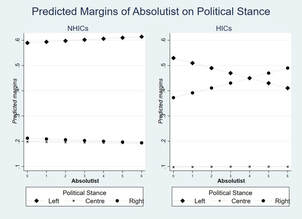

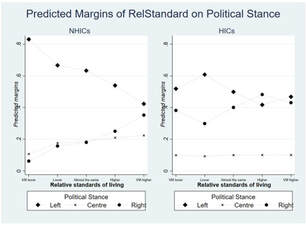

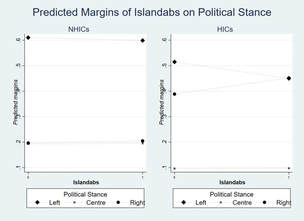

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. by Juliette Faure

Since the mid-2010s, ‘tradition’ has become a central concept in political discourses in Russia. Phrases such as ‘the tradition of a strong state’, ‘traditional values’, ‘traditional family’, ‘traditional sexuality’, or ‘traditional religions’ are repeatedly heard in Vladimir Putin’s and other high-ranking officials’ speech.[1] Paralleling a visible conservative rhetoric hinging on traditional values, the Russian regime demonstrates a clear commitment to technological hypermodernisation. The increased budget for research and development in technological innovation, together with the creation of national infrastructures meant to foster investments in new technologies such as Rusnano or Rostec, and the National Technology Initiative (2014) show a firm intent from the regime.

At the level of official rhetoric, the conservative conception of social order conflicts with a progressive politics of technological modernisation. The Russian president blends a traditionalist approach to social norms based on a fixed definition of human nature,[2] and a liberal approach to technological modernisation emphasising the ideas of innovation, change, speed, acceleration, and breakthrough.[3] The concept of tradition entails cultural determinism and heteronomy: individuals are bounded by a historical heritage and constrained by collective norms. On the contrary, technological modernisation relies on a constant development that strives to push back the limits of the past and nature. In fact, recent studies of science and technology in the post-war USSR increasingly document the positively correlated relations between technoscientific modernisation and political liberalisation. Scientific collaboration with the West,[4] the importation of standards,[5] the multiplication of ‘special regimes’ for scientific communities,[6] and the objectivisation of decision-making through the use of computer science and cybernetics[7] have contributed to the erosion of the Soviet system’s centralisation,[8] the normalisation of its exceptionalism, and its ultimate liberalisation. The USSR arguably failed to sustain itself as a ‘successful non-Western modernity’.[9] The Soviet experience therefore substantiated the technological determinism assumed by liberal-democratic convergence theories.[10] Despite that, there has recently been an increasingly visible effort by contemporary Russian conservative intellectuals to overcome the dichotomy between authoritarian–traditionalist conservatism and technological modernity in order to coherently articulate them into a single worldview.[11]This form of conservatism was already advocated in the late Soviet period by the journalist and writer Aleksandr Prokhanov (1938–). In the 1970s, Prokhanov opposed the domination, among the conservative ‘village prose’ writers, of the idealisation of the rural past and the critique of Soviet modernity.[12] Instead, he aimed to blend the promotion of spiritual and cultural values with an apology of the Soviet military and technological achievements.[13] After the fall of the USSR, Prokhanov’s modernism became commonplace among the members of the younger generation of conservative thinkers, born around the 1970s.[14] Young conservatives framed their views in the post-Soviet context, and regarded technological modernity as instrumental for the recovery of Russia’s status as a great power. One of the leading members of the young conservatives, Vitalii Averianov (1973–), coined the concept of ‘dynamic conservatism’ to describe their ideology. This ideology puts forward an anti-liberal conception of modernity where technology serves the growth of an authoritarian state power and a conservative model of society. Unlike classic conservatism, ‘dynamic conservatism’ resembles the type of political ideology that Jeffrey Herf identified, in the context of Weimar Germany, as ‘reactionary modernism’.[15] The intellectual origins of ‘dynamic conservatism’ across generations of conservative thinkers: Vitalii Averianov and Aleksandr Prokhanov In 2005, ‘dynamic conservatism’ served as the programmatic basis of one of the major contemporary conservative collective manifestos, the Russian Doctrine, co-authored by Vitalii Averianov, Andrei Kobiakov (1961–), and Maksim Kalashnikov (1966–) with contributions from about forty other experts.[16] The Doctrine was put forward as a ‘project of modernisation of Russia on the basis of spiritual and moral values and of a conservative ideology’.[17] The leading instigator of the Doctrine, Averianov, described the ideology advocated by the Russian Doctrine as follows: 'The purpose of the proposed ideology and reform agenda is to create a centaur from Orthodoxy and the economy of innovation, from high spirituality and high technology. This centaur will represent the face of Russia in the 21st century. His representatives should be a new attacking class—imperial, authoritarian, and not liberal-democratic. This should be the class that will support the dictatorship of super-industrialism, which does not replace the industrial order but grows on it as its extension and its development.'[18] In his essay Tradition and dynamic conservatism, Averianov further explains that the ‘dynamic’ aspect of conservatism comes from two paradigmatic shifts that occurred in 20th century’s Orthodox theology and history of science[19]. Firstly, he resorts to the theologian Vladimir Lossky’s (1900–1958) concept of the ‘dynamic of Tradition’. Vladimir Lossky developed this concept in order to address and reform what he perceived as the Orthodox Church authorities’ formal traditionalism and historical inertia. Secondly, Vitaly Averianov appeals to the work of the physicist and Nobel laureate Ilya Prigogine (1917–2003). According to him, the discovery of non-linear dynamic systems disclosed the ‘uncertain’ character of science and offers a post-Newtonian, post-mechanic, and ‘unstable’ view of the world[20]. As Averianov puts it: ‘We situate ourselves at the intersection between Orthodox mysticism and theology, which are embodied by Lossky, who coined the term [of dynamic conservatism], and on the other hand, systems theory and synergetics.’[21] In 2009, the authors of the Russian Doctrine convened in the ‘Institute for Dynamic Conservatism’, which subsequently merged with the ‘Izborsky Club’ founded in 2012 by Aleksandr Prokhanov.[22] Born in 1938, Prokhanov is a well-known figure in Russia as one of the leading ideologues of the putsch against Gorbachev’s regime in August 1991, as a prolific writer of more than sixty novels, and as the current editor-in-chief of the extreme right-wing newspaper Zavtra. In 2006, he articulated a theory about the restoration of the Russian ‘Fifth Empire’, according to which the new Russian ‘imperial style’ should combine ‘the technocratism of the 21st century and a mystical, religious consciousness’.[23] More recently, Prokhanov adopted Averianov’s formula, ‘dynamic conservatism’, to describe his own worldview, which is meant to ‘ensure the conservation of resources, including the moral, religious, cultural, and anthropological resources, for modernisation’.[24] Prokhanov’s reactionary modernism is rooted in the Russian philosophical tradition of ‘Russian cosmism’, which regards scientific and technological progress as humanity’s instruments to achieve the spiritualisation of the world and of human nature.[25] The philosopher Nikolai Fedorov, regarded as the founding figure of Russian cosmism, offered to use technological progress and scientific methods to materialise the Bible’s promises: the resurrection of the dead, the immortality of soul, eternal life, and so on. Fedorov articulated a scientistic and activist interpretation of Orthodoxy, according to which humanity was bound to move towards a new phase of active management of the universe, thereby seizing its ‘cosmic’ responsibility.[26] Following on from Fedorov, 20th-century scientists such as Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, the ‘grandfather’ of the Soviet space programme, or Vladimir Vernadskii, the founder of geochemistry, also belong to the collection of authors gathered under the name ‘Russian cosmism’, since they too advocated a ‘teleologically-oriented’ vision of technological development.[27] Prokhanov and other Izborsky Club members claim the legacy of Russian cosmism in their attempt to craft a specifically Russian ‘technocratic mythology’, as an alternative to the Western model of development.[28] A strategic ideology branded by a lobby group at the crossroads of intellectual and political milieus Introduced as a rallying ‘imperial front’ for the variety of patriotic ideologues of the country (neo-Soviets, monarchists, orthodox conservatives), the Izborsky Club seeks to ‘offer to the Russian government and public […] a new state policy with patriotic orientation’.[29] With more than fifty full members and forty associated experts—including academics, journalists, economists, scientists, ex-military, and clerics[30]—the Club gathers together the largest group of conservative public figures in contemporary Russia. Aleksandr Dugin (1962–), the notorious Eurasian philosopher, is one of its founding members.[31] Despite Dugin’s promotion of Orthodox traditionalism and his critique of technological modernity, his membership of the Club was based on his long-standing relationship with Prokhanov.[32] In this new context of their ideological alliance, Valerii Korovin (1977–), Dugin’s younger disciple and another member of the Izborsky Club, has spelled out a reformed understanding of traditionalism, which regards technological modernity as an instrument for the promotion of Russia as an imperial great power in confrontation with the West: 'We have to separate scientific and technical modernisation and its social equivalent. There is a formula that Samuel Huntington introduced—‘Modernisation without Westernisation’. Russia is developing scientific and technical progress! Our scientists are the best in the world. They create breakthrough technologies. With this, we achieve modernisation while rejecting all Western delights in the field of human experiments. That is—no liberalism, no Western values, no dehumanisation, no mutants, clones, and cyborgs!’[33] In spite of its ideological variety, the Izborsky Club therefore put forward a ‘traditionalist technocratism’ or the ‘combination of ultramodern science with spiritual enlightenment’ as stated in one of its roundtables in September 2018,[34] or as a glance at the Club journal’s iconography rapidly evinces.[35] In blunt opposition to democratic convergence theories, the Izborsky Club brands dynamic conservatism as a strategic ideology for Russia’s development as a great power. The concept of ‘dynamic conservatism’ goes further than simply challenging the normative argument of Francis Fukuyama’s modernisation theory. It also contradicts its empirical claim, which contends that democracy is the regime naturally propelled by the development of modern natural science. Indeed, Fukuyama argues that the success of ‘the Hegelian-Marxist concept of History as a coherent, directional evolution of human societies taken as a whole’ lies in 'the phenomenon of economic modernisation based on the directional unfolding of modern natural science. This latter has unified mankind to an unprecedented degree, and gives us a basis for believing that there will be a gradual spread of democratic capitalist institutions over time.'[36] Based on this technological determinism, liberal modernisation theories claim that economic modernisation, especially in its latest innovation and information based ‘post-industrial’ phase, is incompatible with an authoritarian regime and central planning.[37] What is more, liberal-democratic modernisation’s theorists expect that a ‘post-industrial society’ would eventually lead to the convergence of societies and the ‘end of ideology’.[38] By contrast, ‘dynamic conservatism’ holds that the success and performance of the Russian techno-scientific innovation complex requires the strengthening of the state’s sovereignty under an authoritarian power. They oppose what they perceive as ‘the myth of post-industrialism, aimed at undermining and permanently destroying the real industrial sector of the domestic economy’,[39] and instead advance the need for ‘super-industrialism’ and total ideological mobilisation.[40] In this endeavour, Izborsky Club members frequently refer to the Chinese experience as a lasting challenge to the technological determinism described by liberal modernisation theories. They have voiced their admiration for China’s ability to maintain state ownership and state control in the organisation of its economy. Furthermore, they seek inspiration in China’s process of defining a national idea, the ‘Chinese dream’, combining a ‘harmonious society’ and a technologically advanced economy.[41] Likewise, the Izborsky Club advocates a vision of a ‘Russian dream’ based on a national-scientific and spiritual mythology as an alternative to the ‘American dream’.[42] The Izborsky Club has secured close ties with political, military, and religious elites.[43] The Club’s foundation in 2012 was supported by Andrei Turchak (1975–), who was at the time the governor of the region of Pskov and is now the Secretary-General of the ruling party ‘United Russia’.[44] Moreover, the Club received a financial grant from the presidential administration in its first years of operation. Members of the government or of the presidential administration have often attended the Club’s roundtables and discussions.[45] The Club also entertains close ties with governors and regional political elites in the federal districts, where it has established about twenty local branches.[46] The ideology of dynamic conservatism has also attracted the interest of the Russian Orthodox Church’s authorities. Vitalii Averianov’s experience working for the Church as the former chief editor of the newspaper ‘Orthodox Book Review’ and as chief developer of the most read Orthodox website Pravoslavie.ru, has been key to engaging with the Church at the time of the publication of the Russian Doctrine. Patriarch Kirill (1946–), then Metropolitan and chairman of the Church’s Department of External Relations, displayed public support for the doctrine. In 2007, when discussing the text at the World Russian People’s Council, a forum headed by the Orthodox Church, he declared: ‘This is a wonderful example of Russian social thought of the beginning of the 21st century. I believe that it contains reflections that will still be interesting to people in 10, 15, and 20 years. In addition to purely theoretical interest, this document could have practical benefits if it became an organic part of the national debate on the basic values of Russia.’[47] Finally, the Izborsky Club is vocal about its proximity with the military-industrial complex. The rhetoric, symbols, and iconography used by the Club in its publications portray the army as the natural cradle of the ‘Russian idea’ that they advocate for: ‘Our present military and technical space is the embodiment of the Russian dream.’[48] Beside Prokhanov’s declarations, such as ‘The Izborsky club will help the army prevent an “Orange revolution” in Russia’,[49] actual cooperation with the military-industrial complex has been demonstrated by the regular organisations of the Izborsky Club’s meetings in military-industrial factories. Also significantly, in 2014, a Tupolev Tu-95 bomber was named after the Izborsky Club and decorated with its logo, thereby following the Soviet tradition of naming military airplanes after famous national emblems.[50] In today’s Russia, the patriotic, spiritualised ideology of technological development has been increasingly able to compete with the secular and Western-oriented liberal socio-technical imaginary. This polarity is brought to light by the leadership of technology-related state corporations. The nomination of Dmitrii Rogozin (1963–) as the head of Roscosmos, the state corporation for space activities, in 2018, contrasted with the nomination of Anatolii Chubais (1955–) as the head of Rusnano, the government-owned venture in charge of investment projects in nanotechnologies, in 2008. While Chubais is a symbolic representative of the Russian liberals, as vice-president of the government in charge of the liberalisation and privatisation program of the post-Soviet economy during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency, Dmitrii Rogozin is one of the key leaders of the conservative political elites. He is the former deputy prime minister in charge of defence industry (2011–18), the co-founder of the far-right national-patriotic party Rodina, and a close ally of the Izborsky Club.[51] In line with the agenda advocated by the Izborsky Club, Rogozin has been an active promoter of a nationalist, romantic, and messianic vision of the Russian space programme. According to him: ‘The Russian cosmos is a question of the identity of our people, synonym for the Russian world. For Russia cannot live without space, outside of space, cannot limit the dream of conquering the unknown that drives the Russian soul.’[52] While Vladimir Putin’s discourse runs through a wide and heteroclite ideological spectrum spreading from traditional conservative social values to neoliberal policies of technological development, the ideology of the Izborskii Club flourishes in specific niches in the ruling elites. The impact of their vision on the direction Russia is taking relies on the balance of power negotiated among these elites. [1] Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 12 December 2012, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/17118; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 12 December 2013, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/19825; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 4 December 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/47173; Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 1 December 2016, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/53379. [2] See for instance his references to the Russian people’s ‘genetic code’ and ‘common cultural code’. Vladimir Putin, ‘Direct Line with Vladimir Putin’, President of Russia, 17 April 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20796. [3] This liberal-progressive vocabulary was particularly dominant in Vladimir Putin’s March 2018 address to the Federal Assembly. The discourse included 12 occurrences of the word ‘breakthrough’ (‘proryv’), 60 occurrences of the word ‘development’ (‘razvitie’), 10 occurrences of the word ‘change’ (‘izmenenie’) and 40 occurrences of the word ‘technology’ (‘tekhnologiia’). Vladimir Putin, ‘Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly’, Official website of the President of Russia, 1 March 2018, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957. [4] In 1972, the creation of the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis in Austria provided a place for scientific collaboration between the United States and the USSR until the late 1980s. See Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, The Power of Systems: How Policy Sciences Opened up the Cold War World (Ithaca ; London: Cornell University Press, 2016); Jenny Andersson, The Future of the World: Futurology, Futurists, and the Struggle for the Post Cold War Imagination (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018). [5] As evidenced by the participation of Soviet delegates in the meetings of the Hasting Institute and the Kennedy Center in the United States to establish an ethical framework on biotechnology, and the USSR’s adoption of the DNA manipulation rules of the US National Institute of Health that were established at the Asilomar Summit. Loren R. Graham, ‘Introduction: The Impact of Science and Technology on Soviet Politics and Society’, in Science and the Soviet Social Order, ed. Loren R. Graham (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Pr, 1990), 1–16. [6] Kevin Limonier, Ru.Net: Géopolitique Du Cyberespace Russophone, Carnets de l’Observatoire (Paris : Moscou: Les éditions L’Inventaire ; L’Observatoire, centre d’analyse de la CCI France Russie, 2018). [7] Slava Gerovitch, From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002). [8] Egle Rindzevičiūtė, ‘The Future as an Intellectual Technology in the Soviet Union - From Centralised Planning to Reflexive Management’, Cahiers Du Monde Russe 56, no. 1 (March 2015): 111–34. [9] This argument is developed by Richard Sakwa : ‘the Soviet developmental experiment represented an attempt to create an alternative modernity, but in the end failed to sustain itself as a coherent alternative social order’. See Richard Sakwa, ‘Modernisation, Neo-Modernisation, and Comparative Democratisation in Russia’, East European Politics 28, no. 1 (March 2012): 49; Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, ‘The Civilizational Dimension of Modernity: Modernity as a Distinct Civilization’, International Sociology 16, no. 3 (September 2001): 320–40. [10] As famously articulated in Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York : Toronto : New York: Free Press ; Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; Maxwell Macmillan International, 1992); Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (New York: Basic Books, 1973); Daniel Bell, The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties: With a New Afterword (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988). [11] This argument was also formulated by Maria Engström in Maria Engström, ‘“A Hedgehog Empire” and “Nuclear Orthodoxy”’, Intersection, 9 March 2018, http://intersectionproject.eu/article/politics/hedgehog-empire-and-nuclear-orthodoxy. [12] On the ‘village prose’ movement and the different forms of conservatism in the late Soviet Union, see Yitzhak M. Brudny, Reinventing Russia: Russian Nationalism and the Soviet State, 1953-1991, Russian Research Center Studies 91 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998). [13] See Juliette Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), published online at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13569317.2021.1885591. [14] On the younger generation of Russian conservatives, see Alexander Pavlov, ‘The Great Expectations of Russian Young Conservatism’, in Contemporary Russian Conservatism. Problems, Paradoxes, and Perspectives, ed. Mikhail Suslov and Dmitry Uzlaner (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2020), 153–76. [15] Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). [16] See the list of experts and contributors involved in the writing of the Doctrine: http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95506.html [17] ‘Russkii Sobor Obsudil Russkuiu Doktrinu’, Institute for Dynamic Conservatism (blog), 21 July 2007, http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95525.html. [18] Vitalii Averianov, ‘Nuzhny Drugie Liudi', Zavtra, 14 July 2010, http://zavtra.ru/blogs/2010-07-1431. [19] Vitalii Averianov, ‘Dinamicheskii Konservatism. Printsip. Teoriia. Ideologiia.’, Izborskii Klub (blog), 2012, https://izborsk-club.ru/588. [20] In Order Out of Chaos : Man’s New Dialogue with Nature, that he co-authored with Isabelle Stengers, Ilya Prigogine concludes that science and the ‘disenchantment of the world’ are no longer synonyms. See Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers, Order out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature (London: Flamingo, 1985). [21] Averianov, ‘Dinamicheskii Konservatism. Printsip. Teoriia. Ideologiia.’, art. cit. [22] On the Izborsky Club, see Marlène Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, The Russian Review 75 (October 2016): 634. [23] Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Imperskii Stil’, Zavtra, 30 October 2007, http://zavtra.ru/blogs/2007-10-3111. [24] Quoted in Dmitrii Melnikov, ‘"Valdai" na Beregakh Nevy’, Vesti.ru (2012) : https://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=944192&cid=6 [25] Juliette Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, The Conversation (2021): https://theconversation.com/russian-cosmism-a-national-mythology-against-transhumanism-152780. [26] George Young, The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). [27] Michael Hagemeister, ‘Russian Cosmism in the 1920s and Today’, in The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, Bernice G. Rosenthal (Ed.) (Ithaca ; New York: Cornell University Press, 1997). [28] Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, art. cit. [29] See the ‘about us’ page of the Izborsky Club’s website: https://izborsk-club.ru/about. [30] Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, 634. [31] Other prominent members of the Izborsky Club include the economist Sergei Glaziev, the Nobel Prize physicist Zhores Alferov (1930-2019), Metropolitan Tikhon Shevkunov, the writers Iurii Poliakov and Zakhar Prilepin, leading journalists for Russia’s TV ‘Channel One’ such as Maksim Shevchenko or Mikhail Leontev, who is also the press-Secretary for the state oil company Rosneft. [32] See Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, art. cit., p. 9. [33] ‘Na Iamale Otkrylos Otdelenie Izborskogo Kluba', Izborskii Klub (blog), 1 April 2019, https://izborsk-club.ru/16727. [34] ‘Stenogramma Kruglogo Stola Izborskogo Kluba "V Poiskakh Russkoi Mechty i Obraza Budushchego"’, Izborskii Klub (blog), 10 October 2018, https://izborsk-club.ru/15978. [35] See for instance the cover pages of the Club’s journal 2018 issues : https://izborsk-club.ru/magazine#1552736754837-283c3fe0-bb20 [36] Francis Fukuyama, ‘Reflections on the End of History, Five Years Later’, History and Theory 34, no. 2 (May 1995): 27. [37] Francis Fukuyama reformulates Friedrich Hayek’s argument. See Friedrich Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’, The American Economic Review 35, no. 4 (1945): 519–30. The compatibility between a centralised and authoritarian political system and the development of an economy of innovation was however considered by Joseph Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942, Harper & Brothers). [38] Bell, The End of Ideology, op. cit.; Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society, op. cit. [39] Averianov, ‘Nuzhny Drugie Liudi', art. cit. [40] According to Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘without ideology, there is no state at all’, see Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Raskol Intelligentsii’, Institute for Dynamic Conservatism Website, 11 October 2013, http://dynacon.ru/content/articles/2039/. [41] See for instance Aleksandr Nagornii, ‘Kitaiskaia Mechta Dlia Rossii', Izborskii Klub (blog), 9 April 2013, https://izborsk-club.ru/1130. [42] Faure, ‘Russian Cosmism: A National Mythology Against Transhumanism’, art. cit. [43] Faure, ‘A Russian Version of Reactionary Modernism: Aleksandr Prokhanov’s “Spiritualization of Technology”’, art. cit. [44] The ‘about us’ section of the Izborsky Club website writes : ‘The governor of the Pskov Region A.A. Turchak played an important role in the creation of the Club.’ See : https://izborsk-club.ru/about [45] For instance, the Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinskii took part in the inauguration ceremony of the Club in September 2012. [46] For a list of the Izborky Club delegations in the regions, see : https://izborsk-club.ru/contacts [47] ‘Vsemirnii Russkii Narodnii Sobor Rassmatrivaet "Russkuiu Doktrinu" v Kachestve Natsionalnogo Proekta'’, 28 June 2007, http://www.rusdoctrina.ru/page95531.html. [48] ‘Stenogramma Kruglogo Stola Izborskogo Kluba "V Poiskakh Russkoi Mechty i Obraza Budushchego"’, art. cit. [49] Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Izborskii Klub Pomozhet Armii Predotvratit "Oranzhevuiu Revoliutsiiu" v Rossii', Izborskii Club (blog), 13 March 2019, https://izborsk-club.ru/16616. [50] Laruelle, ‘The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia’, art. cit. [51] Rogozine has founded the Rodina Party with Sergei Glaziev, a permanent and founding member of the Izborsky Club. Regarding his strong personal relationship with Aleksandr Prokhanov, see Aleksandr Prokhanov, ‘Strategicheskii Bombardirovshchisk “Izborskii Club”’, Zavtra, August 21, 2014, http://zavtra.ru/content/view/strategicheskij-bombardirovschik-izborskij-klub/. [52] Dmitrii Rogozin, ‘Rossiia Bez Kosmosa Ne Mozhet Ispolnit Svoi Mechty', Rossiiskaia Gazeta, 11 April 2014, https://rg.ru/2014/04/11/rogozin.html. by Benedict Coleridge

In the course of a 2018 interview undertaken with Jürgen Habermas by the Spanish newspaper El País, the visiting journalists noted that Habermas’ residence, decorated with modern art, presented ‘a juxtaposition of Bauhaus modernism and Bavaria’s staunch conservatism’.[1] While the shelves were lined with the German Romantics, the walls were adorned with icons of European aesthetic modernism, fitting the style of the house itself. In an autobiographical preface to his essays on Naturalism and Religion, Habermas gives an account of the confluence of his decorative and intellectual tastes, highlighting the distinctive experiences and hopes to which they testify. He writes of the post-war revelations that disclosed a civilisational rupture after 1945, along with the sense of cultural release brought about by the doors being opened ‘to Expressionist art, to Kafka, Thomas Mann, and Hermann Hesse, to world literature written in English, to the contemporary philosophy of Sartre and the French left-wing Catholics, to Freud and Marx, as well as to the pragmatism of John Dewey’.[2] He goes on to suggest that ‘contemporary cinema also conveyed exciting messages. The liberating, revolutionary spirit of Modernism found compelling visual expression in Mondrian’s constructivism, in the cool geometric lines of Bauhaus architecture, and in uncompromising industrial design.’[3] Together, these aesthetic movements espoused what Virginia Rembert calls a determination to develop an artistic practice that conveyed a ‘new world image’.[4] And according to Habermas, the ‘cultural opening’ instigated by these aesthetic pursuits ‘went hand in hand with a political opening’, which primarily took the form of ‘the political constructions of social contract theory … combined with the pioneering spirit and the emancipatory promise of Modernism’.[5]