by Joanne Paul

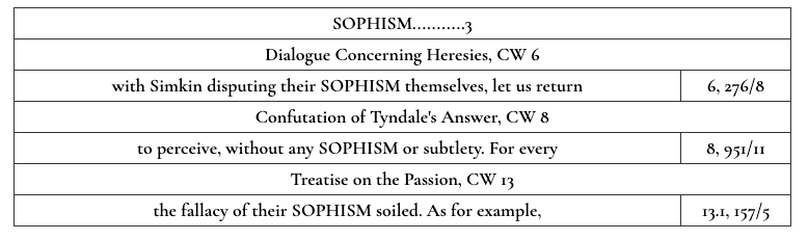

A lot can be said about the relationship between utopianism and ideology, and Gregory Claeys covered much of it in his comprehensive and detailed contribution to this blog.[1] As with all discussions of utopianism, however, participants cannot help but acknowledge the roots of the concept in the originator of the term, Thomas More’s masterfully enigmatic Utopia (full title: On the Best State of the Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia). Whether it was More himself who coined the term (it has been suggested it was in fact Erasmus), and acknowledging the longer (and global) history of imagined ideal states, any consideration of utopianism must at some point trace itself to More’s sixteenth-century text. This can make for some awkward anachronistic connections, especially for anyone concerned particularly with the importance of contextualism in the analysis of historic texts (as I am). Even the question of whether there is an ‘ideology’ present in More’s text can immediately be countered with the charge of anachronism. This is, of course, an issue with the term itself. However, much like we might acknowledge utopias (or utopian thinking) prior to 1516, we might also entertain the suggestion that ideology as a concept (if not a term) might have existed prior to the Enlightenment, and that various contemporary ideologies might also have their roots in the Renaissance, even if More would have been perplexed—but likely intrigued—by the term itself. The purpose of this piece, then, is to explore two interrelated questions. First, whether we can think about ideology and Utopia without giving ourselves entirely over to anachronism and thus a reading of the text that cannot be substantiated. Second, in a similar vein, to test the waters with a variety of ‘ideologies’ with which Utopia has been associated: republicanism, liberalism, totalitarianism/authoritarianism, socialism/communism, and, of course, utopianism. In this ‘testing’, the first criteria will be consistency within the text itself, but in establishing this, I will be reading the text in the context of More’s times and other works. Utopia is too frequently read as a stand-alone text despite—or perhaps because of—More’s substantial oeuvre. It is an intentionally ambiguous work, which is why so many different and even opposed ideologies can be read into it. In order to test the legitimacy of these readings, we must understanding Utopia in the context of More’s work more widely. A short caveat: none of this, of course, precludes the use of Utopia as an inspiration or foundation for a variety of ideological arguments, and Claeys has repeatedly made an impassioned and vitally important argument for the role of utopian thinking in meeting the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century (along with another contribution to this blog by Mathias Thaler)[2]. Political theorists and philosophers have—often very good—reasons for playing harder and faster with the ‘rules’ of historical contextualism (for more on this, see in particular the work of Adrian Blau).[3] There are, however, also good reasons to want to be attentive to the particularities of an utterance in its historical context, which I will not rehearse here, but which I hope are evident in what follows. Ideology and Utopia Does the idea of ‘ideology’ fit with a sixteenth-century intellectual mindset? More was not unfamiliar with the notion of ‘-isms’, often seen as the shorthand for identifying ideologies (though not in the explicitly modern sense).[4] Most of these ‘-isms’ were religious, not just less ‘ideological’ words like baptism, but those that more accurately fit the definition of a ‘system of beliefs’ such as ‘Judaism’, which More used in his Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer (1532).[5] It was the Reformation, Harro Höpfl has noted, which saw the widespread use of ‘isms’ to refer to ‘theological or religious positions considered heretical, and also to refer to the doctrines of various philosophical schools’.[6] Indeed More used the term ‘sophism’ (see the excerpt from the concordance above) in a way that arguably had ideological connotations, and not expressly or necessarily religious ones.[7] That being said, Ideology’s association with political ideas as wholly distinct from religious ones might have not squared with More’s worldview. Any religion can fit the definition of an ‘ideology’ and religious ideas permeated every aspect of More’s world, including—and especially—politics. The way in which Utopia can and has been read as an especially secular text is part of what makes it an enduringly popular text to study, certainly more than More’s other—obviously (and vehemently) religious—writings. There is something attractively secular about More’s pre-Christian island, which is based more obviously on classical pagan influences than medieval Christian ones. For this reason, it is temptingly easy to read a series of ideologies into this short book. The interesting question for a historian like myself becomes whether these were ideas available and attractive to More himself. Republicanism The island of Utopia is obviously and expressly a republic, and the neo-classical humanist More would have fully understood what this entailed. Both books of the text articulate, as Quentin Skinner has demonstrated, arguments for a Ciceronian vita activa, on which republicanism is based.[8] Although each Utopian city is ruled by a princeps, they are elected, and rule in consultation with an assembly of elected ‘tranibors’. The island as a whole is ruled by a General Council, made up of representatives elected from each city. This description of Utopia is framed by a discussion about the merits of the active life in the context of a monarchy, echoing similar discussions in Isocrates, Cicero, Erasmus, and others.[9] Does this align Utopia with ‘republicanism’ as an ideology? Certainly, the text deserves an important place in the development of that ideology from its ‘Athenian and Roman roots’, especially when read in the context of More’s other writings, which express a conciliarism that clearly has overlaps with classical republicanism. In his Latin Historia Richardi Tertii, More writes that parliament, which he calls a senatus, has ‘supreme and absolute’ authority, and in his religious polemics, he is keen to draw a connection between the parliament and the General Council.[10] The latter, he writes, has the power to depose the Pope and, whereas the Pope’s primacy can be held in doubt, ‘the general councils assembled lawfully… the authority thereof ought to be taken for undoubtable’.[11] Both parliament and the General Council are authorised representatives of the whole community, whether the church or the realm.[12] More also expresses ideas in line with what has come to be known as ‘republican liberty’: ‘non-domination’ or ‘that freedom within civil associations’, impling the lack of an ‘arbitrary power’ which would reduce ‘the status of free-man to that of slaves’.[13] In his justification of the importance of law, More writes, that ‘if you take away the laws and leave everything free to the magistrates… they will rule by the leading of their own nature… and then the people will be in no way freer, but, by reason of a condition of servitude, worse’.[14] This aligns with the Renaissance view of tyranny as ruling according to one’s own willful passions, rather than right reason. More certainly saw unfreedom in the rule of licentia (or license) over reason.[15] This could be found both in the rule of a single tyrant and in the anarchy of pluralism, a situation he feared would arise from Lutheranism.[16] As such, a firmly established structure of self-government, like that in Utopia, was the ideal way to ensure his notion of freedom, one that was largely in accordance with the republican tradition. Liberalism This is in contrast with notion of freedom advanced in Utopia by the character Raphael Hythloday, which we might think of as more in line with a ‘liberal’ perspective. He does not want to ‘enslave’ himself to a king and prefers to ‘live as I please’, certainly more ‘license’ than ‘liberty’ in More’s perspective.[17] There is an inherent contradiction between republican and liberal notions of liberty. In so far as More can be said to express something of the former, he is deeply against the latter. Individualism sits at the heart of liberalism; it is, as Michael Freeden and Marc Stears have suggested (though not without qualification), ‘an individualist creed’, seeking to enshrine ‘individual rights, social equality, and constraints on the interventions of social and political power’.[18] Liberalism was a product of the Enlightenment, and so More could not properly be said to be its opponent, but he did powerfully critique what we might see as its nascent constitute parts. In his other works, More often repeats a distinction between the people (populus) and ‘anyone whatever’ (quislibet), to the derision of the authority of the latter.[19] This lies at the heart of his fear of anarchy and Lutheranism, which he accuses of transferring ‘the authority of judging doctrines… from the people and deliver[ing] it to anyone whatever’.[20] In Utopia, we can see this critique of proto-individualism in his central message about pride, which he (with Augustine) takes to be the root of all sin, as it necessarily cuts across the bonds that should unite the populus. Pride is not just self-love, but self-elevation, a form of comparative arrogance that seeks to mark one out from others (a sin he associates with the scholastics, vice-ridden nobility, Lutherans, and indeed most of his opponents). Utopia has thus been read as a repressive regime which quashes—rather than upholds—freedom. This is from the perspective of post-Enlightenment liberalism, and takes Utopia perhaps more literally than it is meant. Read as a critique of the pride which we might associate with a sort of proto-individualism, it offers a powerful critique of an ideology which is—it must be acknowledged—in need of a reassessment. Totalitarianism/Authoritarianism It is for its anti-liberal qualities that Utopia has ended up associated with some of the darkest ideologies of the 20th century. More’s biographer, Richard Marius, called his views about education—certainly present in Utopia—‘an authoritarian concept, suitable for an authoritarian age’. Others have associated Utopia explicitly with totalitarianism.[21] Of the two, authoritarianism might be the more likely. There is a very clear desire in the setting out of the Utopian political and social system to have laws inculcated. The emphasis on what is referred to as ‘education’ or ‘training’ [institutis] might make 21st century readers think instead of socialisation or, more pessimistically, indoctrination. Priests, for example, are responsible for children’s education, and must ‘take the greatest pains from the very first to instil into children’s minds, while still tender and pliable, good opinions which are also useful for the preservation of the commonwealth.’[22] For this, not only are laws and institutions employed, but also public opinion. In a land where everything is public, nothing is private, and thus all is subject to public opinion: ‘being under the eyes of all, people are bound either to be performing the usual labor or to be enjoying their leisure in a fashion not without decency’.[23] This ‘universal behaviour’ is the secret to Utopia’s success. What I think More wanted to draw attention to in Utopia is the way in which this happens anyway, and to reorient the inculcation of values (or ‘opinions’) towards ‘truer’ or more ‘eternal’ (of course even ‘divine’) values. Utopians laugh at gems and precious metals because they associate them with fools and chamber pots. We value them because we associate them with the wealthy and powerful. The Utopians are ‘made’ to be dutiful citizens. As Book One suggests, ‘When you allow your youths to be badly brought up and their characters, even from early years, to become more and more corrupt, to be punished, of course, when, as grown-up men, they commit the crimes from boyhood they have shown every prospect of committing, what else, I ask, do you do but first create thieves and then become the very agents of their punishment?’.[24] In both cases, More suggests in Utopia and elsewhere, these values (or opinions) are built on a sort of ‘consensus’. The suggestion that this is authoritarian stems from a post-Enlightenment perspective that looks to see the liberal individual protected (as set out in part III above), of which More is many ways presenting a sort of ‘proto-critique’. While the republicanism of Utopia would, to some minds (and I would suspect to More’s), prevent it from being accurately labelled authoritarian—the citizenry is, after all, involved in its governance—to others this would not suffice. Would More have minded an ‘authoritarian’ society, if the values it inculcated with the ‘right’ ones? Perhaps not. More’s point, however, that we all submit to and are shaped by various sources of authority, and that the power to reorient the values cultivated by these authorities has been and continues to be a powerful one. Socialism/communism The early socialist thinkers were inspired by More to think that they might make people better through their organisation of society and its institutions (primarily education). In this historical context, we also have to contend, at least for a moment, with utilitarianism, and the Utopian’s ‘hedonism’ (or more properly Epicureanism). Jeremy Bentham, of course, held stock in the factory of utopian socialist Robert Owen. Helen Taylor (stepdaughter of J.S. Mill) wrote that in Utopia More ‘lays down a completely Utilitarian system of ethics’ as well as an ‘eloquently and yet closely reasoned defense of Socialism’. More was not an Epicurean (nor, of course, a utilitarian), though was interested to get back to more ‘real’ or ‘true’ pleasures over those false ones (we might think again of Utopians’ views of gems and precious metals). What I have called his republicanism might have also meant he was more interested in the good of the many over the few, though perhaps not quite in those terms (instead, the common good over any individual good). This emphasis on ‘common good’, of course, translates into ‘common goods’ in Utopia, where everything is held in common. This abolition of anything private (and thus private property) has led him to be read as a socialist and/or communist thinker, the latter not least by Marx and Engels. Beyond Utopia, however, More does make some very un-socialist comments. Through the central figure of Anthony in his Dialogue of Comfort (1534), More suggests in an Aristotelian vein that economic inequality is essential for the commonwealth; there must be ‘men of substance… for else more beggars shall you have’.[25] The golden hen must not be cut up for the few riches one might find inside. The larger point More wants to make in this text, however, is that even the richest do not ‘own’ their property. Property is a fiction and needs to be seen as such. Thus a rich man can keep his wealth so long as he recognises it is only his by the fictions of the society in which he lives, and ought (therefore) to be used to benefit the commonwealth. Wealth, position, and so on, More advocates, ‘by the good use thereof, to make them matter of our merit with God’s help in the life after.’ This is not a socialist nor a communist position, and it is certainly not materialist. More’s entire argument seeks to cultivate a conscious neglect of material realities in favour of the decidedly immaterial. Utopia, then, serves as a reminder of the immaterial realities underneath the social fictions generated in Europe (property, money, social hierarchy, etc). Living in that—shall we say—‘fictive reality’, however, means using those falsities towards the higher ends. As More’s friend John Colet put it: ‘use well temporal things. Desire eternal things.’ Utopianism Utopianism is at once an ideology, has characteristics similar to ideology, might encompass all ideologies, and is entirely opposed to it.[26] I will not rehearse the arguments of Sargent and Claeys here, but the three ‘faces’ that they speak of: utopian literature, utopian communities/practice, and utopian social theory are of course drawn from More’s 1516 text, and Sargent even suggests that ‘the meaning of [utopia] has not changed significantly from 1516 to the present’. So can we accept the obvious, then, that utopianism, as an ideology, is present in More’s text? Unfortunately, this question would seem to hinge on the fraught question of More’s sincerity in setting out the merits of the island of Utopia and the extent to which it is a community that he intended his readers to emulate. In many ways, our answer to this question has the power to overturn the very notion of any ideology being present in at least a surface reading of Utopia. If we were to conclude that Utopia is pure satire, and that the only arguments made in it are negative deconstructive ones, we would be hard-pressed to find any ideology within it at all.[27] I have made my own arguments about the central argument of Utopia, which I will not rehearse here, but the good news is that we can engage with the issue of utopianism in Utopia without answering this seemingly unanswerable question. Say what you will about the difficult question of More’s intentions, it would be difficult indeed to suggest that he was putting forward a blueprint of any kind for the construction of a practical community or endorsing the direct adoption of any of the practices exhibited in Utopia. The idea that Utopia exhibits—to use the words of Crane Brinton—‘a plan [that] must be developed and put into execution’ creates a sense of unease, to say the least. Afterall, More famously ends his text with the conclusion that ‘in the Utopian commonwealth there are very many features that in our own societies I would wish rather than expect to see’.[28] Despite the consensus that this passage is central to our understanding of Utopia, scholars have generally not attempted to read this statement in the context of More’s other works. When we do, we see that More applied this phrase elsewhere as well, and provided more of an explanation than he does in Utopia. In his Apology of 1533, More tells his reader that it would be wonderful if the world was filled with people who were ‘so good’ that there were no faults and no heresy needing punishment. Unfortunately, ‘this is more easy to wish, than likely to look for’.[29] Because of this reality, all one can do is ‘labour to make himself better’ and ‘charitably bear with others’ where he can. It is an internal reorganisation of priorities, drawn in large part from More’s reading of Augustine; what is common and shared must be prioritised over that which is one’s own. This, I have argued elsewhere, is what sits at the heart of More’s oeuvre, and we should be unsurprised to find it in Utopia as well. It is not the case, then, that More is advocating for what we might recognise as utopianism, but rather than Utopia is re-enforcing the arguments he makes elsewhere: the destructive power of pride and the personal need to prioritise the common over the individual. Conclusion: Moreanism? Does this mean, at last, we have come to an ideology in Utopia? A sort of republicanism-light, a proto-communitarianism, an anti-liberalism? I leave it to political theorists to hash out what More’s view might be termed—or indeed if a label is useful at all. Utopia can, indeed, be read in a variety of ways, which support a diversity of ideological positions. It becomes more difficult, I think, to read these positions into More’s thought as a whole. When we examine his corpus, we see a preoccupation with the common good, expressed through representative quasi-republican institutions, and the eternal/immaterial, but also a pragmatism (even ‘realism’?) about the artificialities of the world in which we live. It is the work of a much larger piece to flesh this out in whole, and this small article has instead focused largely on what More cannot be said to be. Hopefully, however, this is in itself a utopian exercise. In understanding Not-More, we might better understand More himself. [1] ‘Utopianism as a Political Ideology: An Attempt at Redefinition’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/04/utopianism-as-a-political-ideology-an-attempt-at-redefinition.html. [2] ‘“We Are Going to Have to Imagine Our Way out of This!”: Utopian Thinking and Acting in the Climate Emergency’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/09/we-are-going-to-have-to-imagine-our-way-out-of-this-utopian-thinking-and-acting-in-the-climate-emergency.html. [3] Adrian Blau, ‘Interpreting Texts’, in Methods in Analytical Political Theory, ed. Adrian Blau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 243–69, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316162576.013. [4] H. M. Höpfl, ‘Isms’, British Journal of Political Science 13, no. 1 (January 1983): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003112. [5] Thomas More, The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More: The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, ed. Louis A. Schuster, Richard C. Marius, and James P. Lusardi, vol. 8 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), 782. [6] Höpfl , ‘Isms’, 1; most of these do not appear in More’s work, though ‘papist’ does (24 times), which is a derivation of ‘papism’; likewise ‘donatists’ (26 times) from ‘donatism’ see https://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance/. Of course, this discussion is of English ‘isms’, and Utopia, along with a handful of More’s other writing, is Latin. Ism itself is a Latin (from Greek, and into French) derivation, for the suffix ‘-ismus’ (masculine). However, text-searches and concordances did not turn up many of these either, nor do ‘isms’ appear in the text of translations consulted. [7] ‘Concordances’, Thomas More Studies (blog), accessed 8 February 2022, http://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance-home/. [8] Quentin Skinner, ‘Thomas More’s Utopia and the Virtue of True Nobility’, in Visions of Politics: Volume 2: Renaissance Virtues (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 213–44. [9] Joanne Paul, Counsel and Command in Early Modern English Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), chapter 1. [10] More, Letters, 321. In the Confutation, 287 he justifies this approach, suggesting that ‘senatus Londinensis’ could be translated ‘as mayor, aldermen, and common council’. [11] More, Letters, 213. [12] More, Confutation, 146, 937. [13] Quentin Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), ix-x. This is not inconsistent with the fact that free-men could indeed become slaves in Utopia. In fact, the presence of slaves only highlights the emphasis on the sort of freedom enjoyed by law-abiding Utopian citizens.[13] Slaves are drawn from either within Utopia - those condemned of ‘some heinous offence’ - or without – captured prisoners of war, those who have been condemned to death in their own country or, thirdly, those who volunteer for it as a preferable option to poverty elsewhere.[13] Notably, in none of these cases is slavery hereditary and slaves cannot be purchased from abroad; Thomas More, More: Utopia, ed. George M. Logan and Robert M. Adams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 77. [14] More, Responsio Ad Lutherum, 277. All references to More’s works taken from the Yale Collected Works series, unless otherwise indicated. [15] Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty, 30-1. [16] Joanne Paul, Thomas More (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 98-9. [17] More, Utopia, 13. [18] Michael Freeden and Marc Stears, ‘Liberalism’, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [19] Paul, Thomas More, 99. [20] More, Responsio, 613. [21] Richard Marius, Thomas More: a biography (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 199), p. 235; Wolfgang E. H. Rudat, ‘Thomas More and Hythloday: Some Speculations on Utopia’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 43, no. 1 (1981): 123–27; J. C. Davis, Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Hanan Yoran, Between Utopia and Dystopia: Erasmus, Thomas More, and the Humanist Republic of Letters (Lexington Books, 2010), 13, 167, 174, 182-3. [22] More, Utopia, 229. [23] More, Utopia, 46. [24] More, Utopia, 71. [25] More, Dialogue of Comfort, 179. [26] Lyman Tower Sargent, ‘Ideology and Utopia’ in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [27] This leads me to address the Erasmus-shaped elephant in the room: what about humanism? Even if Utopia is entirely critical, then the ‘ism’ that might be left standing would be humanism. It’s important to note, however, that humanism has been rather unfortunately named, as scholars agree that it is most definitely not a defined or coherent system of beliefs, but rather a curriculum of learning, an approach to the study of texts and at most a series of questions to which ‘humanists’ provided a variety of answers. One of those question does indeed address the best state of the commonwealth, to which Utopia is a – thoroughly enigmatic – answer. [28] ‘in Utopiensium republica, quae in nostris civitatibus optarim verius, quam sperarim.’ [29] More, Apology, 166. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed