|

29/4/2021 Alternative logics of ethnonationalism: Politics and anti-politics in Hindutva ideologyRead Now by Anuradha Sajjanhar

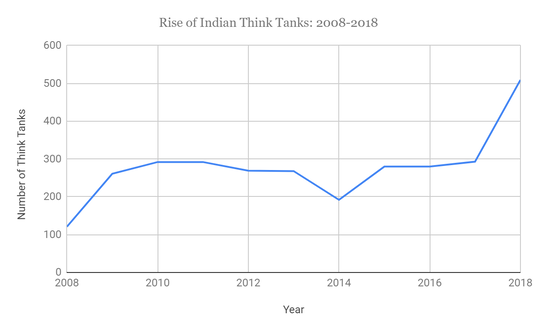

As in most liberal democracies, India’s national political parties work to gain the support of constituencies with competing and often contradictory perspectives on expertise, science, religion, democratic processes, and the value of politics itself. Political leaders, then, have to address and/or embody a web of competing antipathies and anxieties. While attacking left and liberal academics, universities, and the press, the current, Hindu-nationalist Indian government is building new institutions to provide authority to its particular historically-grounded, nationalist discourse. The ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, and its grassroots paramilitary organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), have a long history of sustained Hindu nationalist ideology. Certain scholars see the BJP moving further to the centre through its embrace of globalisation and development. Others argue that such a mainstream economic stance has only served to make the party’s ethno-centric nationalism more palatable. By oscillating between moderation and polarisation, the BJP’s ethno-nationalist views have become more normalised. They have effectively moved the centre of political gravity further to the right. Periods of moderation have allowed for democratic coalition building and wider resonance. At the same time, periods of polarisation have led to further anti-Muslim, Hindu majoritarian radicalisation. This two-pronged dynamic is also present in the Hindu Right’s cultivation of intellectuals, which is what my research is about. Over the last five to ten years, the BJP has been discrediting, attacking, and replacing left-liberal intellectuals. In response, alternative “right-wing” intellectuals have built a cultural infrastructure to legitimate their Hindutva ideology. At the same time, technical experts associated with the government and its politics project the image of apolitical moderation and economic pragmatism. The wide-ranging roles of intellectuals in social and political transformation beg fundamental questions: Who counts as an intellectual and why? How do particular forms of expertise gain prominence and persist through politico-economic conjunctures? How is intellectual legitimacy redefined in new political hegemonies? I examine the creation of an intellectual policy network, interrogating the key role of think tanks as generative proselytisers. Indian think tanks are still in their early stages, but have proliferated over the last decade. While some are explicit about their political and ideological leanings, others claim neutrality, yet pursue their agenda through coded language and resonant historical nationalist narratives. Their key is to effect a change in thinking by normalising it. Six years before winning the election in 2014, India’s Hindu-nationalist party, the BJP, put together its own network of policy experts from networks closely affiliated to the party. In a national newspaper, the former vice-president of the BJP described this as an intentional shift: from “being action-oriented to solidifying its ideological underpinnings in a policy framework”.[1] When the BJP came to power in 2014, people based in these think tanks filled key positions in the central government. The BJP has since been circulating dominant ideas of Hindu supremacy through regional parties, grassroots political organisations, and civil society organisations. The BJP’s ideas do not necessarily emerge from think tank intellectuals (as opposed to local leaders/groups), but the think tanks have the authority to articulate and legitimate Hindu nationalism within a seemingly technocratic policy framework. As primarily elite organisations in a vast and diversely impoverished country, a study of Indian think tanks begs several questions about the nature of knowledge dissemination. Primarily, it leads us to ask whether knowledge produced in relatively narrow elite circles seeps through to a popular consciousness; and, indeed, if not, what purpose it serves in understanding ideological transformation. While think tanks have become an established part of policy making in the US and Europe, Indian think tanks are still in their early stages. The last decade, however, has seen a wider professionalisation of the policy research space. In this vein, think tanks have been mushrooming over the last decade, making India the country with the second largest number of think tanks in the world (second only to the US). As evident from the graph below, while there were approximately 100 think tanks in 2008, they rose to more than 500 in 2018. The number of think tanks briefly dropped in 2014—soon after Modi was elected, the BJP government cracked down on civil society organisations with foreign funding—but has risen dramatically between 2016 and 2018. Fig. 1: Data on the rise of Indian think tanks from Think Tank Initiative (University of Pennsylvania) There are broadly three types of think tanks that are considered to have a seat at the decision-making table: 1) government-funded/affiliated to Ministries; 2) privately-funded; 3) think tanks attached to political parties (these may not identify themselves as think tanks but serve the purpose of external research-based advisors).[2] I do not claim a causal relationship between elite think tanks and popular consciousness, nor try to assert the primacy of top-down channels of political mobilisation above others. Many scholars have shown that the BJP–RSS network, for example, functions both from bottom-up forms of mobilisation and relies on grassroots intellectuals, as well as more recent technological forms of top-down party organisation (particularly through social media and the NaMo app, an app that allows the BJP’s top leadership to directly communicate with its workers and supporters). While the RSS and the BJP instil a more hierarchical and disciplinary party structure than the Congress party, the RSS has a strong grassroots base that also works independent of the BJP’s political elite.

It is important to note that what I am calling the “right-wing” in India is not only Hindu nationalists—the BJP and its supporters are not a coherent, unified group. In fact, the internal strands of the organisations in this network have vastly differing ideological roots (or, rather, where different strands of the BJP’s current ideology lean towards): it encompasses socially liberal libertarians; social and economic conservatives; firm believers in central governance and welfare for the “common man”; proponents of de-centralisation; followers of a World Bank inspired “good governance” where the state facilitates the growth of the economy; believers in a universal Hindu unity; strict adherers to the hierarchical Hindu traditionalism of the caste system; foreign policy hawks; principled sceptics of “the West”; and champions of global economic participation. Yet somehow, they all form part of the BJP–RSS support network. Mohan Bhagwat, the leader of the RSS, has tried to bridge these contradictions through a unified hegemonic discourse. In a column entitled “We may be on the cusp of an entitled Hindu consensus” from September 2018, conversative intellectual Swapan Dasgupta writes of Bhagwat: “It is to the credit of Bhagwat that he had the sagacity and the self-confidence to be the much-needed revisionist and clarify the terms of the RSS engagement with 21st century India...Hindutva as an ideal has been maintained but made non-doctrinaire to embrace three unexceptionable principles: patriotism, respect for the past and ancestry, and cultural pride. This, coupled with categorical assertions that different modes of worship and different lifestyles does not exclude people from the Hindu Rashtra, is important in reforging the RSS to confront the challenges of an India more exposed to economic growth and global influences than ever before. There is a difference between conservative and reactionary and Bhagwat spelt it out bluntly. Bhagwat has, in effect, tried to convert Hindu nationalism from being a contested ideological preoccupation to becoming India’s new common sense.” As Dasgupta lucidly attests, the project of the BJP encompasses not just political or economic power; rather, it attempts to wage ideological struggle at the heart of morality and common sense. There is no single coherent ideology, but different ideological intentions being played out on different fronts. While it is, at this point, difficult to see the pieces fitting together cohesively, the BJP is making an attempt to set up a larger ideological narrative under which these divergent ideas sit: fabricating a new understanding of belonging to the nation. This determines not just who belongs, but how they belong, and what is expected in terms of conduct to properly belong to the nation. I find two variants of the BJP’s attempts at building a new common sense through their think tanks: actively political and actively a-political. In doing so, I follow Reddy’s call to pay close attention to the different ‘vernaculars’ of Hindutva politics and anti-politics.[3] Due to the elite centralisation of policy making culture in New Delhi, and the relatively recent prominence of think tanks, their internal mechanisms have thus far been difficult to access. As such, these significant organisations of knowledge-production and -dissemination have escaped scholarly analysis. I fill this gap by examining the BJP’s attempt to build centres of elite, traditional intellectuals of their own through think tanks, media outlets, policy conventions, and conferences by bringing together a variety of elite stakeholders in government and civil society. Some scholars have characterised the BJP’s think tanks as institutions of ‘soft Hindutva’, that is, organisations that avoid overt association with the BJP and Hindu nationalist linkages but pursue a diffuse Hindutva agenda (what Anderson calls ‘neo-Hindutva’) nevertheless.[4] I build on these preliminary observations to examine internal conversations within these think tanks about their outward positioning, their articulation of their mission, and their outreach techniques. The double-sidedness of Hindutva acts as a framework for understanding the BJP’s wide-ranging strategy, but also to add to a comprehension of political legitimacy and the modern incarnation of ethno-nationalism in an era defined by secular liberalism. The BJP’s two most prominent think tanks (India Foundation and Chanakya Institute), show how the think tanks negotiate a fine balance between projecting a respectable religious conservatism along with an aggressive Hindu majoritarianism. These seemingly contradictory discourses become Hindutva’s strength. They allow it to function as a force that projects aggressive majoritarianism, while simultaneously claiming an anti-political ‘neutral’ face of civilisational purity and inter-religious inclusion. While some notions of ideology understand it as a systematic and coherent body of ideas, Hodge’s concept of ‘ideological complexes’ suggests that contradiction is key to how ideology achieves its effects. As Stuart Hall has shown, dominant and preferred meanings tend to interact with negotiated and oppositional meanings in a continual struggle.[5] Thus, as Hindutva becomes a mediating political discourse, it may risk incoherence, yet defines the terms through which the socio-political world is discussed. The BJP’s think tanks, then, attempt to legitimise its ideas and policies by building a base of both seemingly-apolitical expertise and what they call ‘politically interventionist’ intellectuals. Neo-Hindutva can thus be both explicitly political and anti-political at the same time: advocating for political interventionism while eschewing politics and forging an apolitical route towards cultural transformation. However, contrary to critical scholarship that tends to subsume claims of apolitical motivation within forms of false-consciousness or backdoor-politics, I note that several researchers at these organisations do genuinely see themselves as conducting apolitical, academic research. Rather than wilful ignorance, their acknowledgement of the organisation’s underlying ideology understands the heavy religious organisational undertones as more cultural than political. This distinction takes the cultural and religious parts of Hindutva ‘out of’ politics, allowing it to be practiced and consumed as a generalisable national ethos. [1] Nistula Hebbar, “At Mid-Term, Modi’s BJP on Cusp of Change.” The Hindu. The Hindu, June 12, 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/politics-and-policy/at-mid-term-modis-bjp-on-cusp-of-change/article18966137.ece [2] Anuradha Sajjanhar, “The New Experts: Populism, Technocracy, and the Politics of Expertise in Contemporary India”, Journal of Contemporary Asia (forthcoming 2021). [3] Deepa S. Reddy, “What Is Neo- about Neo-Hindutva?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 483–90. [4] Edward Anderson and Arkotong Longkumer. “‘Neo-Hindutva’: Evolving Forms, Spaces, and Expressions of Hindu Nationalism.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 371–77. [5] Stuart Hall, “Encoding/decoding.” Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks 16676 (2001). |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed