by Marius S. Ostrowski

In May 2021, the British broadcaster ITV launched a new advertising campaign to showcase the range of content available on its streaming platform ITV Hub. In a series of shorts, stars from the worlds of drama and reality TV go head-to-head in a number of outlandish confrontations, with one or the other (or neither) ultimately coming out on top. One short sees Jason Watkins (Des, McDonald & Dodds) try to slip Kem Cetinay (Love Island) a glass of poison, only for Kem to outwit him by switching glasses when Jason’s back is turned. Another has Katherine Kelly (Innocent, Liar) making herself a gin and tonic, opening a cupboard in her kitchen to shush a bound and gagged Pete Wicks (The Only Way is Essex). A third features Ferne McCann (I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, The Only Way is Essex) rudely interrupting Richie Campbell (Grace, Liar) in the middle of a crucial phonecall by raining bullets down on him from a helicopter gunship. And the last, most recent advert shows Olivia Attwood (Love Island) and Bradley Dack (Blackburn Rovers) distracted mid-walk by an adorable dog, only to have a hefty skip dropped on them by Anna Friel (Butterfly, Marcella).

The message of all these unlikely pairings is clear. In this age of binge-watching, lockdowns, and working from home, ITV is stepping up to the plate to give us, the viewers, the very best in premium, popular, top-rated televisual content to satisfy every conceivable taste. Against the decades-long rise of subscription video-on-demand streaming, one of the old guard of terrestrial television is going on the offensive. Netflix? Prime? Disney+? Doesn’t have the range. Get you a platform that can do both. (BAFTA-winning drama and Ofcom-baiting reality, that is.) More a half-baked fighting retreat than an all-out assault? Think again; ITV is “stopping at nothing in the fight for your attention”. Can ITV really keep pace with the bottomless pockets of the new media behemoths? Of course it can. Even without a wealth of resources you can still have a wealth of choice. The eye-catching tagline for all this: “More drama and reality than ever before.” In this titanic struggle between drama and reality, the central irony—or, perhaps, its guilty secret—is how often the two sides of this dichotomy fundamentally converge. The drama in question only very rarely crosses the threshold into true fantasy, whether imagined more as lurid science-fiction or mind-bending Lovecraftian horror; meanwhile, reality is several stages removed from anything as deadening or banal as actual raw footage from live CCTV. Instead, the dramas that ITV touts as its most successful examples of the genre pride themselves on their “grittiness”, “believability”, and even “realism”. At the same time, the “biggest” reality shows are transparently “scripted” and reliant on “set-ups” and other manipulations by interventionist producers, and the highest accolade their participants can bestow on one another is how “unreal” they look. Both converge from different sides on an equilibrium point of simulated, real-world-dramatising “hyperreality”; and as we watch, we are unconsciously invited to ask where drama ends and where reality begins. In our consumption of drama and reality, we are likewise invited to “pick our own” hyperreality from the plethora of options on offer. The sheer quantity of content available across all these platforms is little short of overwhelming, and staying up-to-date with all of it is a more-than-full-time occupation. Small wonder, then, that we commonly experience this “wealth of choice” as decision “fatigue” or “paralysis”, and spend almost as much if not often more time scrolling through the seemingly infinite menus on different streaming services than we do actually watching what they show us. But the choices we make are more significant than they might at first appear. The hyperrealities we choose determine how we frame and understand both the world “out there” within and beyond our everyday experiences and the stories we invent to describe its horizons of alternative possibility. They decide what we think is (or is not) actually the case, what should (or should not) be the case, what does (and does not) matter. Through our choice of hyperreality, we determine how we wish both reality and drama to be (and not to be). Given the quantity of content available, the choice we make is also close to zero-sum. As the “fight for our attention” trumpeted by ITV implies, our attention (our viewing time and energy, our emotional and cognitive engagement) is a scarce resource. Even for the most dedicated bingers, picking one or even a few of these hyperrealities to immerse ourselves in sooner or later comes at the cost of being able to choose (at least most of) the others. We have to choose whether our preferred hyperreality is dominated by “glamorous singles” acting out all the toxic and benign microdynamics of heterosexual attraction, or the murky world of “bent coppers” and the rugged band of flawed-but-honourable detectives out to expose them; whether it smothers us in parasols and petticoats, and all the mannered paraphernalia of period nostalgia, or draws us into the hidden intricacies of a desperately-endangered natural world. In short, we have to choose what it is about the world that we want to see. * * * We face the same overload of reality and drama, and the same forced choice, when we engage with the more direct mediatised processes that provide us with information about the world around us. Through physical, online, and social media, we are met with a ceaseless barrage of new, drip-fed, self-contained events and phenomena, delivered to us as bitesize nuggets of “content”. Before, we had the screaming capitalised headlines and one-sentence paragraphs of the tabloid press. Now, we also have Tweets (and briefly Fleets), Instagram stories and reels, and TikTok videos generated by “new media” organisations, “influencers” and “blue ticks”, and a vast swarm of anonymous or pseudonymous “content providers”. All in all, the number of sources—and the quantity of output from each of these sources—has risen well beyond our capacity to retain an even remotely synoptic view of “everything that is going on”. Of course, it is by now a well-rehearsed trope that these bits of “news” and “novelty” content leave no room for nuance, granularity, and subtlety in capturing the complexities of these events and phenomena. But what is less-noticed are the challenges they create for our capacity to make meaningful sense of them at all from our own (individual or shared) ideological stances. Normally, we gather up all the relevant informational cues we can, then—as John Zaller puts it—“marry” them to our pre-existing ideological values and attitudes, and form what Walter Lippmann calls a “picture inside our heads” about the world, which acts as the basis for all our subsequent thought and action.[1] But the more bits of information we are forced to make sense of, and the faster we have to make sense of them “in live time” as we receive them—before we can be sure about what information is available instead or overall—the more our task becomes one of information-management. We are preoccupied with finding ways to get a handle on information and compressing it so that our resulting mental pictures of the world are still tolerably coherent—and so that our chosen hyperreality still “works” without too many glitches in the Matrix. These processes of information-management are far from ideologically neutral. As consumers of information, our attention is not just passive, there to be “fought over” and “grabbed”; rather, we actively direct it on the basis of our own internalised norms and assumptions. We are hardly indiscriminately all-seeing eyes; we are omnivorous, certainly, but like the Eye of Sauron our voracious absorption of information depends heavily on where exactly our gaze is turned. In this context, what is it that ideology does to enable us to deal with information overload? What tools does it offer us to form a viable representation of the world, to help us choose our hyperreality? * * * One such tool is the iterative process of curating the “recommended-for-you” information that appears as the topmost entries in our search results, home pages, and timelines. The cues we receive are blisteringly “hot”, to use Marshall McLuhan’s term; they are rhetorically and aesthetically marked or tagged—“high-spotted” in Edward Bernays’ phrase—to elicit certain emotional and cognitive reactions, and steer us towards particular “pro–con” attitudes and value-judgments.[2] They “fight for our attention”, clamouring loudly to be the first to be fed through our ideological lenses; and they soon exhaust our capacity (our time, energy, engagement) to scroll ever on and absorb new information. To stave off paralysis, we pick—we have to pick—which bits of information we will inflate, and which we want to downplay. In so doing, we implicitly inflate and downplay the ideological frames and understandings attached to them in “high-spotted” form. Then, of course, the media platform or search engine algorithm remembers and learns our choice, and over time gradually takes the need to make it off our hands, quietly presenting us with only the information (and ideological representations) we “would” (or “should”) have picked out. “Siri, show me what I want to see.” “Alexa, play what I want to hear.” No surprise, then, that the difference in user experience between searching something in our usual browser or a different one can feel like paring away layers of saturation and selective distortion. The fragmentary nature of how we receive information also changes how we express our reaction to it. The ideologically-exaggerated construction of informational cues is designed to provoke instant, “tit-for-tat” responses. At the same time, the promise of “going viral” creates an algorithmic incentive to move first and “move mad” by immediately hitting back in the same medium with a response that is at least as ideologically exaggerated and provocative as the original cue if not more. Gone are the usual cognitive buffers designed to optimise “low-information” reasoning and decision-making. Instead, we are pushed towards the shortest of heuristic shortcuts, the paths of least intellectual resistance, into an upward—and outward (polarising)—spiral of “snap” judgments. The “hot take” becomes the predominant way for us to incorporate the latest information into our ideological pictures of the world; any longer and more detailed engagement with this information is created by literally attaching “takes” to each other in sequence (most obviously via Twitter “threads”). As this practice of instantaneous reaction becomes increasingly prominent and entrenched, our pre-existing mental pictures are steadily overwritten by a worldview wholly constituted as a mosaic of takes: disjointed, simplistic, foundationless, and subjective. As our ideological outlook becomes ever more piecemeal, we turn with growing urgency to the tools and structures of narrative to bring it some semblance of overarching unity. Every day, we consult our curated timelines and the cues it presents to us to discover “the discourse” du jour—the primary topic of interest on which our and others’ collective attention is to focus, and on which we are to have a take. Everything about “the discourse” is thoroughly narrativised: it has protagonists (“the OG Islanders”) and a supporting cast (“new arrivals”, “the Casa Amor girls”), who are slotted neatly into the roles of heroes (Abi, Kaz, Liberty) or villains (Faye, Jake, Lillie); it undergoes plot development (the Islanders’ “journeys”), with story and character arcs (Toby’s exponential emotional growth), twists (the departure of “Jiberty”) and resolutions (the pre-Final affirmations of “Chloby”, “Feddy”, “Kyler”, and “Milliam”). We overcome both the sheer randomness of events as they appear to us, and the pro–con simplicity of our judgments about them, by reimagining each one as a scene in a contemporary (im)morality play—a play, moreover, in which we are partisan participants as much as observers (e.g., by voting contestants off or adding to their online representations). How far this process relies on hermetically self-contained, self-referential certainty becomes clear from the discomfort we feel when objects of “the discourse” break out of this narrative mould. The howls of outrage that the mysterious figure of “H” in Line of Duty turned out not to be a “Big Bad” in the style of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but instead a floating signifier for institutional corruption, shows how conditioned we have become to crave not only decontestation but substantial closure. The final element in our ideological arsenal that helps us cope with the white heat of the cues we receive is our ability to look past them and focus on the contextual and metatextual penumbra that surrounds them. To make sure we are reading our fragmentary information about the world “correctly”, we search for additional clues that take (some or all of) the onus of curating it, coming up with a take about it, and shaping it into a narrative off our hands. This explains, for instance, the phenomenon where audiences experience Love Island episodes on two levels simultaneously, first as viewers and second as readers of the metacommentary in their respective messenger group chats, and on “Love Island Twitter”, “Love Island TikTok”, and “Love Island Instagram”. In extreme cases, we outsource our ideological labour almost entirely to these clues, at the expense of engaging with the information itself, as it were, on its own terms. “Decoding” the messages the information contains then becomes less about knowing the right “code” and more about being sufficiently familiar with who is responsible for “encoding” it, as well as when, where, and how they are doing so. Rosie Holt has aptly parodied this tendency, with her character vacillating between describing a tweet as nice or nasty (“nicety”) and serious (“delete this”) or a joke (“lol”), incapable of making up her mind until she has read what other people have said about it. * * * Together, these elements create a kind of modus vivendi strategy, which we can use to cobble together something approaching a consistent ideological representation of what is going on in the world. But its highly in-the-moment, “choose-your-own-adventure” approach threatens to give us a very emaciated, flattened understanding of what ideology is and does for us. Specifically, it is a dangerously reductionist conception of what ideology has to offer for our inevitable project of choosing a hyperreal mental picture that navigates usefully between (overwhelming, nonsensical) reality and (fanciful, abstruse) drama. If a modus vivendi is all that ideology becomes, we end up condemned to seeing the world solely in terms of competing “mid-range” narratives, without any overarching “metanarratives” to weave them together. These mid-range narratives telescope down the full potential extent of comparisons across space and trajectories over time into the limits of what we can comprehend within the horizons of our immediate neighbourhood and our recent memory. What we see of the world becomes limited to a litany of Game of Thrones-style fragmentary perspectives, more-or-less “(un)reliable” narrations from myriad different people’s angles—which may coincide or contradict each other, but which come no closer to offering a complete or comprehensive account of “what is going on”. The tragic irony is that the apotheosis of this information-management style of ideological modus vivendi is taking place against a backdrop of a reality that is itself taking on ever more dramatic dimensions on an ever-grander scale. Literal catastrophes such as climate change, pandemics, or countries’ political and humanitarian collapse raise the spectral prospect of wholesale societal disintegration, and show glimpses of a world that is simultaneously more fantastical and more raw than what we encounter as reality day-to-day. Individual-level, “bit-by-bit” interpretation is wholly unequipped to handle that degree of overwhelmingness in the reality around us. Curating the information we receive, giving our takes on it, crafting it into moralistic narratives, and interpreting its supporting cues is a viable way to offer an escape (or escapism) from the stochastic confusion of the “petty” reality of our everyday experience—to “leaven the mundanity of your day”, as Bill Bailey puts it in Tinselworm. But it falls woefully short when what we have to face is a reality that operates at a level well beyond our immediate personal experience, which is “sublimely” irreducible to anything as parochial as individual perspective. How unprepared the ideological modus vivendi calibrated to the mediatisation of information today leaves us is shown starkly by the comment of an anonymous Twitter user, who wondered whether we will experience climate change “as a series of short, apocalyptic videos until eventually it’s your phone that’s recording”. If it proves unable to handle such “grand” reality, ideology threatens to become what the Marxist tradition has accused it of being all along: namely, an analgesic to numb us out of the need to take reality on its own ineluctable terms. That, ultimately, is what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were trying to provide through their accounts of historical materialism and scientific socialism: an articulation of a narrative capable of addressing, and as far as possible capturing, the sheer scale and complexity of reality beyond the everyday. We do not have to take all our cues from Marxism—even if, as often as not, “every little helps”. But we do have to inject a healthy dose of grand narrative and metanarrative back into the ideologies we use to represent the world around us, even if only to know where we stand among the tides of social change from which the “newsworthy” events and phenomena we encounter ultimately stem. The trends driving the reality we want to narrate are simultaneously global and local, homogenised and atomised, universal and individuated. We cannot focus on one at the expense of the other. By itself, neither the “Olympian” view of sweeping undifferentiated monological macronarratives (Hegelian Spirit, Whig progress, or Spenglerian decline) nor the “ant’s-eye” view of disconnected micronarratives (of the kind that contemporary mediatisation is encouraging us to focus on) will do. The only ideologies worth their salt will be those that bridge the two. How, then, should ideology respond to the late-modern pressures that are generating “more drama and reality than ever before”? Certainly, it needs to recognise the extent to which these are opposite pulls it has to satisfy simultaneously: no ideological narrative can afford to lose the contact with “gritty” reality that makes it empirically plausible, nor the “production values” of drama that make it affectively compelling. At the same time, it has to acknowledge that the hyperreality it creates and chooses for us is never fully immune to risk. Dramatic “scripting” imposes on reality a meaningfulness and direction that the sheer chaotic randomness of “pure” reality may always eventually belie. Meanwhile, the slavish drive to “accurately” simulate reality may ultimately sap our orientation and motivation in engaging with the world around us of any dramatic momentum. The only way to minimise these risks is to “think big”, and restore to ideology the ambition of “grand” and “meta” perspective, to reflect the maximum scale at which we can interpret both what (plausibly) is and what (potentially) is to be done. [1] Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (Blacksburg, VA: Wilder Publications, Inc., 2010 [1922]), 21–2; John R. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 51. [2] Edward Bernays, Propaganda (Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2005 [1928]), 38; Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (New York, NY: McGraw–Hill, 1964), 22ff. by Eileen M. Hunt

Mary Shelley is most famous for writing the original monster story of the modern horror genre, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). She was also the author of the pandemic novel that unleashed the dominant tropes of post-apocalyptic literature upon modern political science fiction. Her fourth completed novel, The Last Man (1826), pictured the near annihilation of the human species by an unprecedented and highly pathogenic plague that surfaces during a war between Greece and Turkey in the year 2092. Shelley’s dystopian worlds, in turn, have inspired Marxist social and political theorists in their Promethean critiques of capitalism. Both Frankenstein’s monster and Shelley’s monster pandemic resonate with us during the time of Covid-19 because of the power and prescience of her iconic critiques of human-made disasters.

While she lived in Italy with her husband Percy, Shelley helped him translate and transcribe Plato’s Symposium, which contains the etymological origin of the English word “pandemic” (in ancient Greek, πάνδημος).[1] In Plato’s philosophical dialogue on the meaning of love, the goddess “Pandemos” is the “earthly Aphrodite” who oversees the bodily loves of “all” (pan) “people” (demos), men and women alike.[2] In the aftermath of the 1642-51 English Civil Wars and the 1665–66 Great Plague of London, the adjective “pandemic” gained salience in both political and medical contexts in seventeenth-century English. It could refer to either the disorders of democratic government by all people (as in monarchist John Rogers’s 1659 condemnation of the “unjust Equality of Pandemick Government”), or the visitation of pestilence to undermine the stability of the entire body politic (as in doctor Gideon Harvey’s 1666 description of “Endemick or Pandemick” diseases that “haunt a Country”).[3] According to this conceptual genealogy sketched by literary theorist Justin Clemens, two important homophonic variants of “Pandemick” emerged in the aftermath of the English Civil Wars. Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) defined “Panique Terror” as a contagious “passion” of fear that happens to “none but in a throng, or a multitude of people.”[4] Then John Milton invented the word “pandaemonium” for his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) to depict Satan’s hell as a kingdom where all the little devils lived in sin-infected chaos.[5] Indebted to her deep reading of Plato, Hobbes, and Milton, Shelley’s The Last Man conceived the global plague as an “epidemic” that affects or touches upon (epi) all (pan) people (demos) precisely because it stems from the disruptions of collective human corruption, panic, and politics.[6] In her first novel, Shelley had metaphorically rendered the revenge of Frankenstein’s “monster” upon his uncaring scientist-maker as an unstoppable “curse,” “scourge,” and “pest” upon their family and potentially “the whole human race.”[7] This unnamed “creature” was nothing less than a “catastrophe,” brought to life by the chemist Victor Frankenstein from an artificial assemblage of the dead parts of human and nonhuman animals.[8] His dark motivation for using his knowledge of chemistry, anatomy, and electricity to bring the dead back to life was the sudden loss of his mother to scarlet fever while she cared for his sick sister, cousin, and bride-to-be, Elizabeth. In her second great work of “political science fiction,” Shelley found new horror in reversing the direction of the metaphor.[9] No longer was the monster a plague: the plague itself was the monster. Shelley not only wrote the origin story for modern sf with Frankenstein. She also laid down the ur-text for modern post-apocalyptic fiction in The Last Man. With her great pandemic novel, Shelley panned out to see all plagues as human-made monstrosities that leave “a scene of havoc and death” behind them.[10] What made plagues so ghastly was their exponential power to multiply—causing a concatenation of disasters for their human authors, other afflicted people, and their wider environments on “a scale of fearful magnitude.”[11] In The Last Man, Shelley conceived all plagues—real and metaphorical—as human contaminations of wider environments. Bad human behaviors corroded the people closest to them, then spread like toxins through the cultural atmosphere to destroy the health and happiness of others. The ancient plagues of erotic and familial conflict, war, poverty, and pestilence had reproduced together and persisted into modernity through centuries of modelling, imitation, and replication of humanity’s worst behaviors in culture, society, and politics. Midway through The Last Man, the Greek princess Evadne issues an apocalyptic prophecy: humanity would soon be incinerated in a vortex of war, passion, and betrayal.[12] As she dies of “crimson fever” on a pestilential battlefield, she curses her beloved and the leader of the Greek forces Lord Raymond for abandoning her for his wife Perdita. “Fire, war, and plague,” she cries, “unite for thy destruction!”[13] As if on cue, the seasonal “visitation” of “PLAGUE” in Constantinople escalates into an international pandemic. With her uncanny insight into the social genesis of epidemics and other plagues upon humanity, Shelley—through the voice of Evadne—anticipated the economic and political theory of pandemics that has gained currency in the twenty-first-century. Back in 2005, the Marxist historian Mike Davis warned the world that zoonotic viral pandemics like the avian flu and SARS-CoV—whose genetically mutated strains enabled them to leap from nonhuman animals to a mass of human victims—were The Monster at Our Door.[14] While Davis did not cite Shelley in his book, he didn’t need to: the allusion to Frankenstein was perfectly clear in the title. Davis was writing in a long tradition of reading the monster imagery of Frankenstein through the technological lenses of Marxism. Based in London for much of his career, Marx himself was likely influenced by the massive cultural impact of Shelley’s Frankenstein and her husband Percy’s radical political poetry, as they filtered through the nineteenth-century British socialist tradition.[15] Despite his stubborn dislike of Marxist hermeneutics and other social scientific readings of literature, the critic Harold Bloom was always the first to admit that “it is hardly possible to stand left of (Percy) Shelley.”[16] Given his revolutionary-era philosophical debts to Rousseau, Wollstonecraft, and Godwin, it is not surprising that Percy Shelley felt outraged by the news of the August 1819 “massacre at Manchester.”[17] The British calvary charged an assembly of 60,000 workers, killing some and injuring hundreds more. While living in exile in Italy with his pregnant wife, in deep mourning over the recent losses of their toddler William to malaria and infant Clara to dysentery, Percy composed a timeless lyric to summon the poor to non-violent protest. Not published until 1832 due to the poet's untimely death in 1822 and the poem's controversial argument, “The Mask of Anarchy” became an anthem for the peaceful liberation of people from the slavery of poverty and political oppression: "Rise like Lions after slumber In unvanquishable number-- Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you-- Ye are many—they are few."[18] Completed two years before Percy’s rousing defense of popular uprising against the power of the imperial state, Frankenstein made a parallel political point. Literary scholar Elsie B. Michie underscored that the tragic predicament of Frankenstein’s abandoned Creature fit what Marx would call, in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, the plight of “alienated labor.”[19] Modern capitalistic society cruelly severed the poor from the material sources and products of their own making. Frankenstein likewise left his Creature bereft of any benefits of the “bodies,” “work,” and “labours” by which “the being” had been shaped into “a thing” such as “even Dante could not have conceived.”[20] When read against the background of Shelley’s novel, Marx’s theory of alienated labor recalls the dynamic of confrontation and separation that drives the conflicted yet magnetic relationship of the Creature with his technological maker. Taken out of the context of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, some of Marx’s words could easily be mistaken for a commentary on Frankenstein, as in: “the object that labour produces, its product, confronts it as an alien being, as a power independent of the producer.”[21] While capitalism produced the workers from its elite economic control of the tools of science, technology, and economics, the workers received no benefit from those same tools that a truly benevolent maker might have otherwise bestowed upon them. What could such a creature do but confront their maker with a demand for the goods necessary for the development of their humanity? In his 1857-58 “Fragment on Machines” from the Grundrisse, Marx rather poetically captured the process of human alienation from the products of their own technological labors: "Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified."[22] Reworking the twin Greek myths of Prometheus, in which the titan molds humanity from clay and then forges the mortals’ rebellion from the gods through the gift of fire, Marx follows Shelley in depicting human beings as self-replicating machines: for they are artificial products of their own willful mind to dominate and transform nature through technology. As the political philosopher Marshall Berman argued in All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (1983), Marx’s bourgeoisie is a Promethean “sorcerer” akin to “Goethe’s Faust” and “Shelley’s Frankenstein,” for it created new and unruly forms of artificial life that in turn raised “the spectre of communism” for modern Europe.[23] What Mike Davis has done so brilliantly, in the spirit of both Marx and the Shelleys, is to use this nineteenth-century techno-political imaginary to conceptualise humanity’s responsibility for the self-destructive course of pandemics in our time. Generations of readers of Frankenstein have felt compelled to pity the Creature, despite his train of crimes, and come to view him as a product of the fevered madness of his father-scientist. In this rhetorically persuasive Shelleyan tradition, Davis pushes his readers to see Covid-19 and other pandemics as products of the myopic mindsets of the human beings who selfishly let them loose upon the world. With the rise of the novel coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, Davis stoically set up his home office in his garage. As most countries around the globe went under lockdown during the endless winter of 2020, he sat down to update his book The Monster at Our Door for the second time.[24] Like Shelley and many writers of political science fiction after her, from Octavia Butler to Margaret Atwood to Emily St. John Mandel, the historian had predicted that a new, deadly, and devastating severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) would visit the planet in the twenty-first century.[25] Reports from the World Health Organisation had sparked Davis’s concerns about the latest iteration of the avian flu, or H5N1 influenza.[26] H5N1 had fast and lethal outbreaks in 1997 and 2003—while exhibiting a terrifying 60% mortality rate.[27] It passed from chickens to humans in Hong Kong in 1997, and, on a much more alarming scale, through “commercial poultry farms” in South Korea, China, Thailand, Vietnam, and other regions of Southeast Asia in 2003, via a “highly pathogenic” and “novel strain,” H5N2.[28] Like the epidemiologists, ecologists, and anthropologists whose work he studied, the historian feared that the “Bird flu” could erupt into a pandemic that might kill more than the deadliest virus of the twentieth century.[29] Davis recounted that an estimated “40 to 100 million people”—including his “mother’s little brother”—had been taken by the H1N1 avian influenza of 1918.[30] The newspapers at the time described the pandemic as the “Spanish Flu,” even though it started in the United States and elsewhere.[31] Because Spain remained neutral during the First World War, its press went uncensored. Spanish newspapers took the lead in reporting cases of the rising international wave of influenza. Far from war-torn continental Europe, the first recorded human outbreak of this flu mutation—which swiftly flew from birds to people—in fact began in a rural farming community and military base in Kansas.[32] A dreadful re-run of 1918 loomed in our near future, Davis insisted, if nations did not prepare for the worst. Governments needed to reduce “the virulence of poverty,” improve health care, and stockpile medical and protective equipment.[33] They had to regulate international trade, factory farming, and flight travel with an eye toward protecting public health from a resurgence of uncontrolled zoonotic viral respiratory infections. And they must support the best virology and vaccine research before the next epidemic snowballed into a global economic and political disaster. Under lockdown last April, Davis changed the title of his updated book to The Monster Enters, to mark a shift in his historical perspective. Just a few weeks earlier, disease ecologist Peter Daszak announced in a New York Times op-ed that we had officially entered the “age of pandemics.”[34] The monster pandemic of our political nightmares was no longer the threat of the avian flu at our door. It had already entered our world as SARS-CoV-2—a novel coronavirus thought to have been initially transmitted from bats to humans near Wuhan, China—and it was leaving a mounting set of economic, social, and political disasters in its wake. More of these novel and volatile contagions stood on the horizon like shadows of Frankenstein’s creature cast over the Earth. “As the hour of the pandemic clock ominously approaches midnight,” Davis had reflected on the last page of The Monster at Our Door, “I recall those 1950s sci-fi thrillers of my childhood in which an alien menace or atomic monster threatened humanity.”[35] Without vaccines to stop their circulation across nations, these viral mutations threatened to destroy their human creators like Frankenstein’s creature had done. Ironically, they could upend the globalised economic and political systems that had proliferated their diseases through international trade, travel, and economic inequality. Never purely natural phenomena, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and the latest strain of the avian flu were in fact the products and “plagues of capitalism.”[36] In the chapter titled “Plague and Profit,” Davis made explicit his debt to both Marx and Shelley. He gave the name “Frankenstein GenZ” to the virulent “H5N1 superstrain—genotype Z.”[37] At the turn of the twenty-first century, poultry factories in China unwittingly bioengineered this deadlier strain of H5N1, in the aftermath of the 1997 outbreak in Hong Kong. By inoculating ducks with an “inactivated virus” and breeding them for slaughter in their processing plants, they created a new and potentially levelling form of the avian flu, H5N2.[38] Almost two centuries before our current historical seer Mike Davis, Mary Shelley saw the monster pandemic coming for us in the future. The concluding volume in my trilogy on Shelley and political philosophy for Penn Press--The Specter of Pandemic—is about why she and some of her followers in the tradition of political science fiction have been able to predict with uncanny accuracy the political and economic problems that have beset humanity in the “Plague Year” of two thousand and twenty to twenty-one.[39] For Shelley, the reasons were deeply personal. She experienced an epidemic of tragedies on a depth and scale that most people could not bear. During the five years she lived in Italy from 1818 to 1823, the young author, wife, and mother saw the infectious diseases of dysentery, malaria, and typhus fell three children she bore or cared for, before her husband Percy drowned, at age twenty-nine, in a sailing accident off the coast of Tuscany. Her emotional and intellectual resilience in the face of the many plagues upon her family is what made her a visionary sf novelist, existential writer, and political philosopher of pandemic. [1] Justin Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus; or, Pandemic, Panic, Pandaemonium,” Crisis & Critique 7:3 (2020), 41-60; Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert, eds., The Journals of Mary Shelley (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, [1987] 1995), 220. [2] Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus,” 47-48. [3] Ibid., 43, 45. [4] Ibid., 50. [5] Ibid., 52. [6] Shelley, The Last Man, 183. In March 1820, Shelley noted Percy’s reading Hobbes’s Leviathan, sometimes, it seems, “aloud” to her. See Shelley, Journals, 311-313, 345. The epigraph for Frankenstein is drawn from Book X of Milton’s Paradise Lost: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay/To mould me man? Did I solicit thee/From darkness to promote me?” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism, ed. J. Paul Hunter, second edition (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 2. [7] Shelley, Frankenstein, 69, 102, 119. [8] Ibid., 35. [9] Eileen Hunt Botting, Artificial Life After Frankenstein (Philadelphia: Penn Press, 2020), introduction. [10] Mary Shelley, The Last Man, in The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley, ed. Jane Blumberg with Nora Crook (London: Pickering & Chatto, [1996] 2001), vol. 4, 176. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid., 139. [13] Ibid., 144. [14] Mike Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu, and the Plagues of Capitalism (New York: OR, 2020). [15] Chris Baldick, In Frankenstein’s Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 132, 137. [16] Harold Bloom, Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The Power of the Reader’s Mind over a Universe of Death (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 183. [17] “Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘The Mask of Anarchy (1819),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/PShelley/anarchy.html. [18]Ibid. [19] “Elsie B. Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Articles/michie1.html. [20] Shelley, Frankenstein, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36. [21] “Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990).’” [22] Karl Marx, “The Fragment on Machines,” The Grundrisse (1857-58), 690-712, at 706. Accessed 28 November 2020 at https://thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf [23] Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983), 101. [24] Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu (New York: New Press, 2005); Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu. Revised and Expanded edition (New York: Macmillan, 2006). [25] Eileen Hunt Botting, "Predicting the Patriarchal Politics of Pandemics from Mary Shelley to COVID-19," Front. Sociol. 6:624909. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.624909 [26] Davis, The Monster Enters, 87-100. [27] Natalie Porter, Viral Economies: Bird Flu Experiments in Vietnam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 2. [28] Porter, Viral Economies, 1-2.; Davis, The Monster Enters, 120-23. [29] Ibid. [30] Davis, “Preface: The Monster Enters,” in The Monster at Our Door, 44-47. [31] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin, 2004), 171. [32] Ibid., 91. “1918 Pandemic Influenza Historic Timeline | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC,” April 18, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/pandemic-timeline-1918.htm. [33] Davis, The Monster Enters, 53. [34] Peter Daszak, “Opinion | We Knew Disease X Was Coming. It’s Here Now.,” The New York Times, February 27, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/opinion/coronavirus-pandemics.html. Davis cites Daszak’s article with David Morens and Jeffery Taubenberger, “Escaping Pandora’s Box: Another Novel Coronavirus,” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (2 April 2020) in his introduction to The Monster Enters, 3, 181. [35] Davis, The Monster Enters, 180. [36] See the subtitle of Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu and the Plagues of Capitalism. [37] Davis, The Monster Enters, 119, 122 [38] Ibid. [39] Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations Or Memorials of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as Well Publick as Private, Which Happened in London During the Last Great Visitation in 1665 (London: E. Nutt, 1722). by Marta Lorimer

Far-right parties are frequently, and not without cause, painted as fervent Eurosceptics, or even ‘Europhobes’. Ideologically nativist, and usually placed at the margins of the political system, these parties appear as almost naturally inclined to oppose a supranational construction generally supported by mainstream actors. But how accurate is this narrative? Are far-right parties really naturally ‘Eurosceptic’, and what does it even mean to be ‘Eurosceptic’?

A cursory look at the history of the far right should give one reason for pause. For starters, several of the parties that are today seen as Europhobes started off as pro-EU and have also generally benefitted enormously from the EU’s existence. Take the French Rassemblement National (RN, previously, Front National) as an example. In the 1980s, long before Marine Le Pen spoke about Frexit, her father made his first appearance on the national scene in European elections and insisted that Europe ‘shall be imperial, or shall not be’.[1] More broadly, knowing how these parties feel about the EU tells us very little about what they think about Europe beyond the narrowly construed project of the EU. Indeed, their language is replete with references to a European (Christian) civilisation worth protecting, claims seemingly at odds with the rabid opposition by many of them to the European Union. In my research on the relation between the far right and Europe, I attempt to make sense of these tensions by analysing how far-right parties conceive of Europe through ideological lenses, and the effects that approaching Europe in a certain way has. I advance two key arguments: first, I hold that the depiction of far-right parties as ‘naturally’ Eurosceptic is misleading. Second, I posit that these parties’ positions on European integration served the broader purpose of legitimising them by making them appear more palatable to a general public. These claims are developed empirically through the in-depth study of how the Italian Social Movement/Alleanza Nazionale (MSI/AN) in Italy and the Rassemblement National in France integrated Europe in their ideological frames over the period 1978-2017, and to what effects. What do they talk about when they talk about Europe? Let us start with the first of the two claims, namely, that the depiction of far-right parties as ‘naturally’ Eurosceptic is misleading. To develop this point, it is pertinent to take a step back and ask first ‘but what do far-right parties talk about when they talk about Europe’? One way to address this question is to analyse the concepts that these parties commonly associate with Europe in their party literature.[2] In the MSI/AN and RN’s ideology, three in particular stand out: the concepts of identity, liberty, and threat. In each of these key concepts, the parties express an ambivalent view of Europe at odds with the term ‘Eurosceptic.’ The concept of identity refers to a category of identification that allows groups to define who they are, through considerations of the positive (and negative) aspects of the group they belong to. The MSI/AN and RN rely on this concept to define Europe as a distinct civilisation. The MSI, for example, spoke in favour of European unity conscious of the ‘community of interests and destinies, of history, of civilisation, of tradition among Europeans’,[3] while Jean-Marie Le Pen spoke of Europe as ‘A historic, geographic, cultural, economic, and social ensemble. It is an entity destined for action’.[4] This understanding is not one that is strictly time-bound, and as late as 2017, Marine Le Pen could affirm that for her party ‘Europe is a culture, it’s a civilisation with its values, its codes, its great men, its accomplishments its masterpieces […] Europe is a series of peoples whose respective identities exhale the fecund diversity of the continent’.[5] Importantly, both the MSI/AN and RN consider themselves as part of this civilisation and view it as compatible with their national identity. As the MSI/AN put it, ‘Individuality (in this case national) and community (in this case European) are not in opposition but in reciprocal integration and vivification’.[6] In addition to approaching Europe through the prism of identity, the MSI/AN and RN also rely on the concept of liberty to define it. Liberty, as it is understood in their discourse, is an essential attribute of the nation and corresponds to central principles of autonomy, self-rule, and power in the external realm. It is also understood as a collective term: the bearer of ‘liberty’ is not the individual, but the nation intended as a holistic community. The relation between liberty and Europe, however, changes significantly through time. In the 1980s, the RN and the MSI spoke of Europe as a space in need of ‘liberty’ in face of the ‘twin imperialisms’ of the USA and the USSR. This was also associated with the need to re-establish Europe as an international power which could not only defend its nations, but also, reinforce their global influence. From the end of the 1980s, however, and particularly for the RN, ‘liberty’ shifted from being an attribute of Europe to being an endangered part of the national heritage. The introduction of the Single European Act and the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty contributed significantly to this shift (although they are not the only factors).[7] These treaties did little to make the EU into a strong international actor, as they privileged economic integration over integration in matters of foreign policy and defence. Furthermore, by setting the EU on an increasingly federal path, they were at odds with the RN’s view that European unity should happen in the form of a vaguely-defined (but clearly confederal) ‘Europe of the Nations’. As a result, the RN starts speaking increasingly about ‘sovereignty’ as a ‘collective form of liberty’ endangered by the EU. The final concept that the parties draw upon to define Europe is that of threat, with Europe presented as a community endangered by a variety of threats such as the USSR in the 1970s and 1980s, the USA in the 1980s and 1990s, and decline and migration throughout. While the nature of threats varies across parties and across time, Europe and its nations always appear to be threatened by some evil force that requires swift intervention. As with liberty, however, the relation between Europe and threat changes over time: whereas in the 1980s, Europe was mainly an endangered community (and indeed, a potential source of protection from external threats), since the 1990s, Europe in the shape of the EU has become a threat in and of itself. This is particularly true for the RN, which since the 1990s has identified globalisation as a growing threat, and the EU as its vector. Europe, in this sense, went from being an instrument which could protect from ‘others’, to an ‘other’ which could facilitate the demise of nation states by facilitating the instauration of a new, globalised world order. As will have become evident, the MSI/AN and RN’s approach to Europe shows more nuance than the term ‘Eurosceptic’ fully captures, and ‘Euro-ambivalence’ seems to be a better descriptor of their positions. Whereas the EU has frequently been an enemy (although more so for the RN than for the MSI/AN), this was not always the case, and ‘Europe’ remained a positively valued concept throughout. This ambivalence is grounded in three elements: First, political ideologies are notoriously flexible: while one might expect some degree of continuity, they are also deeply contextual and can evolve over time and depending on historical and national circumstances. In this sense, ambivalence emerges both synchronically across countries and diachronically over time depending on contextual changes. Second, the European Union is a complex construction in constant evolution. Whereas it started as a small economic union of Western European countries, it has evolved into a deeply political construction encompassing a large part of the European continent. Far-right parties’ ambivalence therefore partially depends on which aspect of the EU they are looking at, and at what phase of its historical development. Finally, for as much as the EU tries to equate the two, ‘Europe’ and the EU remain two different constructions. The EU is but one embodiment of the idea of Europe, and the far right’s ambivalence about Europe also derives from swearing allegiance to ‘Europe’ while rejecting the political construction of the EU. As the party statutes of the far right ‘Identity and Democracy’ group in the European Parliament show, far-right parties are willing to acknowledge that Europeans share a common ‘Greek-Roman and Christian heritage’ and consider that this heritage creates the bases for ‘voluntary cooperation between sovereign European nations.’ However, they also reject the EU and its attempts to become ‘a European superstate’.[8] Summing up, while today we tend to see far-right parties as Eurosceptic, this was not always the case, and neither does the term fully capture the complexity of their positions. Ambivalence about Europe is an important part of the far right’s approach to Europe, and can help us understand why far-right parties can collaborate transnationally in the name of ‘another Europe’ different from the EU. Europe as ideological resource In addition to being ambivalent about Europe, far-right parties also have a marked tendency to benefit from it. The EU has, in fact, provided these parties with symbolic and material resources that have helped them become established actors. Electorally, the proportional system of representation employed in EU elections made it easier for far-right parties to gain representation. This has also come with a gain in resources which could be used to improve their standing in domestic elections.[9] Far-right parties have also sought to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the EU, for example by employing alliances in the European Parliament to enhance legitimacy at home.[10] One might ask how speaking about Europe in a certain way may have helped the far right. A plausible answer to this question is that Europe presented an ideological resource for far-right parties looking for legitimation because it allowed them to reorient their ideology in a more acceptable fashion and speak both to their traditional electorate and to new supporters.[11] An ideological resource, as I define it, is a device that offers political parties an opportunity to revise and reframe their political message in a more appealing way. Europe is one such resource. As a relatively new political issue, and one which has no clear ideological answer, it leaves parties, including far-right ones, with some leeway in determining the position they adopt. As such, it makes it possible for them to craft a position that is appealing to their traditional voters and to new voters alike. In addition, the divisiveness of European integration can benefit far-right parties because it makes dissent more acceptable. Because European integration has divided political parties and electorates alike, it is a topic on which disagreement is acceptable and where it may be easier for parties to present a more widely appealing political message. To illustrate this argument, it is worth looking at two specific discourses employed by the RN in association with the previously discussed concepts of identity and liberty: its claim to be ‘pro-Europe and anti-EU’ and its growing focus on questions of sovereignty, autonomy, and independence. As discussed earlier, the RN has since the 1980s claimed to be ‘pro-European’, however, since the end of the 1980s it has also increasingly pitted its support for Europe against the European Union. For example, a 1991 party guide draws a distinction between ‘two Europes’ holding that ‘The first conception is that of a cosmopolitan or globalist Europe, the second is that of a Europe understood as a community of civilisation. The first one destroys the nations, the second one ensures their survival. The first one is an accelerator of decline, the second an instrument of renaissance. The first is the conception of the Brussels technocrats and of establishment politicians, the second is our conception.’[12] More recently, Marine Le Pen has claimed that ‘even though we are resolutely opposed to the European Union, we are resolutely European, I’d go as far as saying that it is because we are European that we are opposed to the European Union’.[13] The claim to be pro-Europe but anti-EU serves the dual purpose of attracting new voters by presenting them a ‘softer’ and less nationalist face, all the while maintaining the old ones by relying on the notion of a closed identity that is key to traditional RN discourse. Speaking of Europe in these terms, then, makes it possible for the RN to construct a more legitimate image, without, however, losing the support of its existing electoral base. The RN’s reliance on ideas of sovereignty, independence, and autonomy to criticise the EU serves a similar purpose. When the party says things like ‘A nation’s sovereignty is its ability to take decisions freely and for itself. It refers then to the notions of independence and exercise of political power by a legitimate government. The entire history of the European construction consists of depriving States of their sovereignty’,[14] it is both speaking about elements that are perfectly compatible with its own nationalist ideology, and drawing on more common discourses about the nation that may carry broader appeal. These critiques also resonate with critiques of the EU presented by actors with no association with the far right, an element which may provide them with an additional ‘ring of truth’. In sum, while opposition to European integration is frequently presented as a marker of marginalisation for parties, when well phrased it can in fact function as a powerful tool for legitimation that far-right parties can seize upon. Where to for the far right and Europe? Simplification is often necessary in the social sciences; however, it is worth remembering that even seemingly straightforward associations can be more complicated than one thinks. The link between far-right ideology and opposition to ‘Europe’ is one of these associations that seems intuitive, but which conceals a more variegated picture made of a history of support for European integration, attachment to a different ‘Europe’, and a penchant for benefitting from a project it explicitly rejects. Understanding and appreciating the ‘Euro-ambivalent’ nature of far-right parties can help make sense of some recent phenomena such as the transnational collaboration of nationalists. Because many of these parties share a common vision of Europe, they can leverage it to justify their collaboration on an international scale as part of a project to defend Europe from the EU.[15] They have also been able to collaborate because they found cooperation beneficial: namely, it served to portray them as a unified and growing movement, carrying ever greater political weight and forming the main axis of opposition to the cosmopolitan elites. Crucially, however, one should not assume that a far-right takeover or destruction of the EU institutions is in the making or ever likely to happen. On the one hand, while far-right parties do benefit from some ideological flexibility, the nation and the national interest remain their guiding principles. Thus, while the far right may be able to argue that they are both nationalists and Europeans, in case of conflict, it is unlikely that their commitment to Europe will ever trump the nation. In the improbable event that far-right parties did engineer a takeover of EU institutions, it is also doubtful that they would actively seek to dismantle them. Europe, after all, has its uses, and it is likely that they will be willing to take advantage of some of them. More likely, the far right would try to transform the EU into something more compatible with their own worldview; however, what this ‘Europe of the Nations’ would look like, or how it would function, remains mostly unclear. What is more problematic for the EU in the short term is that much of the far right’s criticism contests core assumptions about the EU institutions, and runs counter some of the solutions brought forward to tackle its own legitimacy deficit. For example, the centrality of the concept of Identity to far-right parties’ definition of Europe raises questions about the feasibility of promoting a ‘European identity’ as a solution to the EU’s legitimacy issues. At the same time, the far right’s claims to be ‘pro-Europe but anti EU’ bring to the fore the contestedness of the concept of Europe, and create a counter-narrative of Europe which questions the very premise that the EU is the embodiment of Europe. Reopening that equation to contestation removes one of the EU’s legitimising narratives, suggesting that the way ahead for the EU will remain paved with opposition. In sum, even if far-right parties may not be able to coalesce to dismantle the EU or orchestrate a takeover of its institutions from the inside, they can still rock it to its very core. [1] J.-M. Le Pen, J. Brissaud, & Groupe des Droites européennes. (1989). Europe: discours et interventions, 1984-1989 (Issue Book, Whole). Groupe des Droites européennes. [2] M. Lorimer. (2019). Europe from the far right: Europe in the ideology of the Front National and Movimento Sociale Italiano/Alleanza Nazionale (1978-2017). London School of Economics and Political Science. [3] Movimento Sociale Italiano. (1980). Il Msi-Dn dalla a alla zeta : principii programmatici, politici e dottrinari esposti da Cesare Mantovani, con presentazione del segretario nazionale Giorgio Almirante . Movimento sociale italiano-Destra nazionale, Ufficio propaganda. [4] J.-M. Le Pen. (1984). Les Français d’abord. Carrère - Michel Lafon. [5] M. Le Pen. (2017). Discours de Marine Le Pen à la journée des élus FN au Futuroscope de Poitiers.. [6] Movimento Sociale Italiano, 1980. [7] M. Lorimer. (forthcoming) ‘The Rassemblement National and European Integration,’ in Berti, F. and Sondel-Cedarmas, J., ‘The Right-Wing Critique of Europe: Nationalist, Sovereignist and Right-Wing Populist Attitudes to the EU’, London: Routledge. [8] Identity and Democracy. (2019). Statutes of the Identity and Democracy Group in the Europeaan Parliament. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/kantodev/pages/102/attachments/original/1582196570/EN_Statutes_of_the_ID_Group.pdf?1582196570; M. Lorimer. (2020b). What do they talk about when they talk about Europe? Euro-ambivalence in far right ideology. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(11), 2016–2033. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1807035. [9] E. Reungoat. (2014). Mobiliser l’Europe dans la compétition nationale. La fabrique de l’européanisation du Front national. Politique européenne, 43(1), 120–162. https://doi.org/10.3917/poeu.043.0120; J. Schulte-Cloos. (2018). Do European Parliament elections foster challenger parties’ success on the national level? European Union Politics, 19(3), 408–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518773486 [10] D. McDonnell & A. Werner. (2019). International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament. Hurst; N. Startin. (2010). Where to for the Radical Right in the European Parliament? The Rise and Fall of Transnational Political Cooperation. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2010.524402. [11] M. Lorimer. (2020a). Europe as ideological resource: the case of the Rassemblement National. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(9), 1388–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1754885. [12] Front National. (1991). Militer Au Front. Editions Nationales. [13] M. Le Pen, 2017. [14] Front National. (2004). Programme pour les élections européennes de 2004. [15] A point perceptively made by McDonnell and Werner, 2019 as well. by Erik van Ree

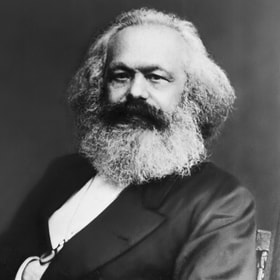

Measured against the number of those who called themselves his followers, and given the speed with which these “Marxists” after 1917 laid hands on a substantial part of the globe, Karl Marx, in death if not in life, was one of the most successful people that ever lived. He falls in the category of conquerors, Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan, or of religious prophets with the stature of Jesus of Nazareth and Mohammed. The spectacular collapse of much of the communist world, of course, substantially detracts from Marx’s posthumous success, but it doesn’t annul “Marxism’s” earlier triumphs.