by Jack Foster and Chamsy el-Ojeili

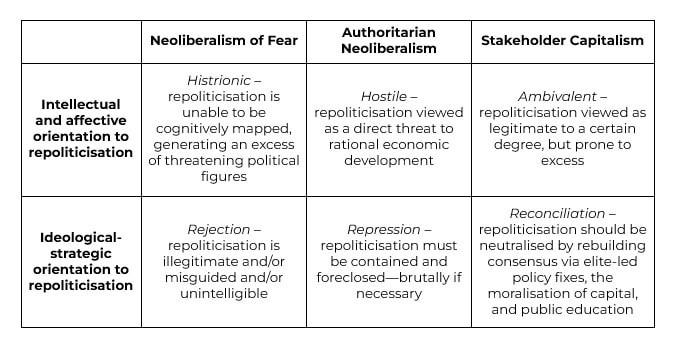

In September 2021, penning his last regular column for the Financial Times after 25 years of writing on global politics, Philip Stephens reflected on a bygone age. In the mid-1990s, an ‘age of optimism’, Stephens writes, ‘the world belonged to liberalism’. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the integration of China into the world economy, the realisation of the single market in Europe, the hegemony of the Third Way in the UK, and the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance presaged a century of ‘advancing democracy and a liberal economic order’. But today, following the financial crash of 2008 and its ongoing fallout, and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘policymakers grapple with a world shaped by an expected collision between the US and China, by a contest between democracy and authoritarianism and by the clash between globalisation and nationalism’.[1] Only five months later, the editors of the FT judged that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had definitively closed the ‘chapter of history opened by the fall of the Berlin Wall’; the sight of armoured columns advancing across the European mainland signals that a ‘new, darker, chapter has begun’.[2] At this juncture, with the all-consuming immediacy of the war in Ukraine, and the widespread appeal of framing the conflict in civilisational terms—Western liberal democracy facing down an archaic, authoritarian threat from the East—it is worth reflecting on some of the currents that flow beneath and give shape to the discourse of Western liberal elites today. In a previous essay, we argued that the leading public intellectuals and governance institutions of Western capitalism have struggled to effectively interpret and respond to the political and economic turmoil first unleashed by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008.[3] We traced out a crisis of intellectual and moral leadership among Western elites in the splintering of (neo)liberal discourse over the past decade-and-a-half—the splintering of what was, prior to the GFC, a relatively consensual ‘moment’ in elite discourse, in which cosmopolitan neoliberalism had reigned supreme. As has been widely argued, the financial crisis brought this period of confidence and self-congratulation to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Both the enduring economic malaise that followed the crash, and the crisis of political legitimacy that has unfolded in its wake, have shaken the intellectual and ideological certitude of Western liberals. All political ideologies experience ‘kaleidoscopic refraction, splintering, and recombination’, as they are adapted to historical circumstances and combined with elements of other worldviews to produce novel formations.[4] However, we argued that the post-GFC period has seen a particularly intense and marked splintering of (neo)liberal discourse into three distinctive but overlapping and intertwining strands or ‘moments’. First, a neoliberalism of fear,[5] which is animated by the invocation of various dystopian threats such as populism, protectionism, and totalitarianism, and which associates the contemporary period with the extremism and instability of the 1930s. Second, a punitive neoliberalism, which seeks to conserve and reinforce existing power relations and institutions of governance.[6] And third, a pragmatic and reconciliatory neo-Keynesianism, oriented above all to saving capitalism from itself. In this essay, we want to expand upon one aspect of this analysis. Specifically, we suggest here that one way in which we can distinguish between these three strands or ‘moments’ is as distinct responses to the repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management in the years following the GFC. Respectively, these responses can be summarised as rejection, repression, and reconciliation (see Table 1, below). Depoliticisation and repoliticisation In our previous essay, we argued that the 1990s and early 2000s were marked by the predominance of cosmopolitan neoliberalism as a successful project of intellectual and moral leadership, the moment of the ‘end of history’ and ‘happy globalisation’. In this period, we saw the radical diminution of economic and social alternatives to capitalism, the colonisation of ever more spheres of social life by the market, the transformation of common sense around the proper relationship between states and markets, the public and the private, equality and freedom, the community and the individual, and the institutionalisation of post-political management, or what William Davies has called ‘the disenchantment of politics by economics’.[7] Of this last, neoliberalism, as both a political ideology and a set of institutions, has always been oriented to the active depoliticisation and indeed dedemocratisation of ‘the economy’ and its management—what Quinn Slobodian calls the ‘encasement’ of the market from the threat of democracy.[8] In practice, this has been pursued in two primary ways. First, it has been accomplished via the legal and institutional insulation of ‘the economy’ from democratic contestation. Here, the delegation of critical public policy decisions to unelected, expert agencies such as central banks and the formulation of rules-based economic policy frameworks designed to narrow political discretion are emblematic. Second, this has been buttressed by ideological appeals to the constraints placed upon domestic economic sovereignty by globalisation and the necessity of technocratic expertise in government—strategies that lay at the heart of the Clinton administration in the US (‘It’s the economy, stupid!’) and the Third Way of Tony Blair in the UK. Economic management was to be left to Ivy League economists, central bankers, and the financial wizards of Wall Street and the City. The so-called ‘Great Moderation’—the period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that was characterised by low macroeconomic volatility and sustained, albeit unspectacular, growth in most advanced economies—lent credence to these ideas. The hubris of elites in this period should not be underestimated. As Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the influential Bank for International Settlements, put it to an audience of European financiers in 2019, ‘During the Great Moderation, economists believed they had finally unlocked the secrets of the economy. We had learnt all that was important to learn about macroeconomics’.[9] And in his ponderous account of how global capitalism might be saved from the triple-threat of financial instability, Covid-19, and climate change, former governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney recalls ‘how different things were’ prior to the credit crash—a period of ‘seemingly effortless prosperity’ in which ‘Borders were being erased’.[10] The GFC catalysed both an epistemological crisis in mainstream economics, and, after some delay, the rise of anti-establishment political forces on both the left and the right. The widespread failure to reflate economic development in the wake of the crisis and the punishing effects of austerity in the UK and the Eurozone, and at the state level in the US, only exacerbated the problem. Over the past decade-and-a-half, questions of economic development, of who gets what, and of who should be in charge, have come back on the table. How have Western elites responded? Rejection One dominant response to this repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management has been to invoke a host of dystopian figures—populism, nationalism, political extremism, protectionism, socialism, and totalitarianism—all of which are perceived as threats to the stability of the open-market order, to economic development, and to a thinly defined ‘liberal democracy’. This is the neoliberalism of fear Four years prior to the election of Donald Trump, the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks’ assessment was already grimly warning that the ‘seeds of dystopia’ were borne on the prevailing winds of ‘high levels of unemployment’, ‘heavily indebted governments’, and ‘a growing sense that wealth and power are becoming more entrenched in the hands of political and financial elites’ following the GFC.[11] In 2013, Eurozone technocrats were raising cautious notes around the ‘renationalisation of European politics’.[12] By 2015, Martin Wolf, long-time economics columnist for the FT, was informing his readers that ‘elites have failed and, as a result, elite-run politics are in trouble’.[13] This climate of fear reached fever-pitch in 2016, with the shocks delivered by the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, and again in January 2021, with mounting fears that President Biden’s inauguration would be blocked by a truculent Republican party. The utopian world of the long 1990s, in which globalisation was ‘tearing down barriers and building up networks between nations and individuals, between economies and cultures’, in the words of Bill Clinton, has thus disappeared precisely as ‘the economy’ and its management began to be repoliticised.[14] Two aspects of this often-histrionic neoliberalism of fear stand out. First, we see a striking inability to cognitively map the repoliticised terrain. Rather than serious attempts to map out why and in what ways repoliticisation is occurring, this strand or ‘moment’ is characterised by a reliance on a set of questionable historical analogies, above all the 1930s and the disasters of totalitarianism. Second, extraordinary weight is given over to these threats and fears, and there is a corresponding absence of serious attempts to construct a new ideological consensus. Instead, repoliticisation is countered in a language that is defensive, hectoring, and dismissive. For Wolf, populist forces have organised to ‘muster the inchoate anger of the disenchanted and the enraged who feel, understandably, that the system is rigged against ordinary people’.[15] In like fashion, former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, reflecting on his role in resolving the GFC, writes that in crises, ‘fear and anger and ignorance’ clouds the judgement of both the public and their representatives and impedes sensible policymaking; it is essential, in times of crisis, that decisions are left to coldly rational technicians.[16] Musing on the integration backlash in the EU, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, noted that while ‘protectionism is society’s natural response’ to unchecked market forces, it is crucial to ‘resist protectionist urges’, and this is the job of enlightened technocrats and politicians, who must hold back the populist forces threatening to roll back market integration.[17] In other words, while recognising that a rampaging globalisation has driven social and political unrest, within this neoliberalism of fear the masses are viewed as too capricious and ignorant to be trusted; the post-GFC malaise, while frightening and disorienting, will certainly not be solved by more democracy. Repression Closely related to, and overlapping with, this neoliberalism of fear is the second core strand or ‘moment’, that of a punitive and coercive neoliberalism. If the neoliberalism of fear can be understood as a dismissive overreaction to repoliticisation, this second strand represents a more direct and focused attempt to manage this new, more unstable, and more contested political economy. Fears of deglobalisation, of protectionism, of fiscal recklessness are also prominent in this line of argument; however, equally prominent are the necessary solutions: strengthening the rules-based global order, ongoing flexibilisation and integration of labour and product markets—particularly in the EU—and a harsh but altogether necessary process of fiscal consolidation. The problem of public debt has, of course, been one of the major battlegrounds here. Preaching the necessity of fiscal consolidation at the elite Jackson Hole conference in 2010, for example, Jean-Claude Trichet raised the cautionary tale of Japan, a country that ‘chose to live with debt’ in the 1980s and suffered a ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s as a result.[18] These concerns were widely echoed in the financial press and by international policy organisations; here, the threat of market discipline was also consistently evoked as justification for fiscal retrenchment and punishing austerity. As former IMF economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff infamously warned, prudent governments pay down public debt, because ‘market discipline can come without warning’.[19] Much has been made of the punitive, moralising, and post-hegemonic dimensions of this discourse.[20] However, it is worth bearing in mind that there are also genuine attempts to match the policy prescriptions associated with this more authoritarian and coercive neoliberalism—fiscal austerity, enhanced fiscal discipline and surveillance, structural adjustment, rules-based economic governance—with a positive vision of the political economy that these policies will deliver: economic growth, global economic stability, a route out of the post-GFC doldrums. Viewed in this way, the key ideological thrust here seems to be less that of punishment for punishment’s sake than it is of the deliberate repression and foreclosure of repoliticisation. Pace the classical neoliberal thinkers, the driving logic is that economic development and economic management are far too important to be left to democracy, which is altogether too fickle and too subject to capture by interest groups to be trusted. The upshot? Austerity, flexibilisation, the strengthening of the elusive rules-based global order: all this must be pushed through regardless of dissent. As with any ideological formation, shutting down alternative arguments is also important. As one speaker at the Economist’s 2013 ‘Bellwether Europe Summit’ put it, ‘the political challenge’ to structural adjustment ‘comes not from the process of adjustment itself. People can accept a period of hardship if necessary. It comes from the belief that there are better alternatives available that are being denied’.[21] In these ways, this second strand or ‘moment’ is directly hostile to the return of the political: less a hurried and defensive pulling-up of the drawbridge, as in the neoliberalism of fear, than a concerted counterattack. Reconciliation While this punitive and coercive neoliberalism seeks to repress repoliticisation by further insulating ‘the economy’ and its management from democratic interference, the third main strand of post-GFC (neo)liberal discourse responds to repoliticisation in a more measured way. In our previous writing on this issue, we referred to this strand or ‘moment’ as a pragmatic neo-Keynesianism, which promotes technocratic policy fixes aimed at lightly redistributing wealth and rebuilding the social contract. Over the past couple of years, we suggest, these more reconciliatory energies have coagulated into a relatively coherent ideological project, that of stakeholder capitalism.[22] Simultaneously, aided by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism of the 2010s has been discredited and has largely vanished from the pages of the financial press, the policy recommendations of the major international organisations, and the books and columns of Western public intellectuals. Thus, we use the term stakeholder capitalism to refer to the recent ideological shift in the Western policy establishment, among public intellectuals, and in business and high finance, that centres around the push for more ‘socially responsible’ corporations, for ‘green finance’, and for the re-moralisation of capitalism. By 2019, this shift was gathering momentum. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz implored readers of the New York Times to help build a ‘progressive capitalism’, ‘based on a new social contract between voters and elected officials, between workers and corporations, between rich and poor, and between those with jobs and those who are un- or underemployed’.[23] The FT launched its ‘New Agenda’, informing its readers that ‘Business must make a profit but should serve a purpose too’.[24] The American Business Roundtable, the crème de la crème of Fortune-500 CEOs, issued a new ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’, in which it revised its long-standing emphasis on promoting shareholder-value maximisation. Rather than narrowly focusing on returning profit to their shareholders, it now claims that corporations should ‘focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone—investors, employees, communities, suppliers, and customers’.[25] Similarly, the WEF launched its 50th-anniversary ‘Davos Manifesto’ on the purpose of a company, promoting the development of ‘shared value creation’, the incorporation of environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into company reporting and investor decision-making, and responsible ‘corporate global citizenship […] to improve the state of the world’.[26] And no lesser figure than Jaime Dimon, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, noted in his 2019 letter to shareholders that ‘building shareholder value can only be done in conjunction with taking care of employees, customers and communities. This is completely different from the commentary often expressed about the sweeping ills of naked capitalism and institutions only caring about shareholder value’.[27] Now, in early 2022, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, has announced that it will be launching a ‘Center for Stakeholder Capitalism’ in the near future.[28] The term ‘stakeholder management’ was originally coined by the business-management theorist Edward Freeman in the 1980s,[29] but the roots of this discourse go back to the dénouement of the first Gilded Age, where some business leaders began to promote the idea of the socially responsible corporation as a means of outflanking working-class discontent during the Great Depression.[30] The concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ then became popular in the 1990s, associated above all with the Third Way of New Labour.[31] Today, the discourse of stakeholder capitalism has been resurrected and updated, we suggest, in direct response to the repoliticisation of the economy and its management and the failure of authoritarian neoliberalism to provide a way out of the post-2008 quagmire. At the root of this rebooted version of stakeholder capitalism is an argument for the re-moralisation of capitalism in the interests of social cohesion and long-term sustainability. To be sure, there remains a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, consumer choice, and so on. But there is also a recognition of—or at least the payment of lip service to—the fact that a rampaging globalisation and widespread commodification has undermined social stability and cohesion. Thus, in contrast to the second strand or ‘moment’ of post-GFC (neo)liberalism, stakeholder capitalism seeks to deal with the repoliticisation of the economy and its management by establishing a more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. To establish a more inclusive capitalism means making some relatively significant shifts in economic policy. ‘[T]argeted policies that achieve fairer outcomes’ are the order of the day.[32] A more fiscally active state and investment in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D are all called for. So too is an expanded social-welfare safety net, primarily in the form of active labour-market policies. And above all, stakeholder capitalism is about tackling the green-energy transition, which presents, for boosters of a private-finance-led transition, ‘the greatest commercial opportunity of our time’.[33] This means ‘smart’ state intervention to steer and ‘derisk’ private investment.[34] Cultural reform, economic education, and democratic renewal are also viewed as important enabling features of this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. Here, policymakers must lead from the front, finding ways to better communicate with, and to educate, citizens and to foster consensus. In these respects, if the ‘moment’ of punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism was characterised by the repression of repoliticisation, then stakeholder capitalism seeks reconciliation. But while the legitimacy of democratic dissatisfaction is broadly recognised, and while there is a place for ‘more democracy’ in the discourse of stakeholder capitalism, this is democracy conceptualised not as the meaningful contestation of the distribution of power and resources, but as a relentless machine for building consensus. Opposing value systems and fundamental conflicts over the distribution of resources do not exist, only ‘stakeholder engagement’ oriented to revealing the ‘public interest’ or the preferences of ‘society’ at large. Exponents of stakeholder capitalism call for more education on how the economy works and emphasise the need to ‘listen’ more attentively to the citizenry. But the intention behind such endeavours is to develop or fortify consensus around already-existing institutions, or at best to tweak them at the margins. In these respects, there is an ambivalence running through this third—and perhaps now dominant—strand or ‘moment’: the mistrust of democracy, made explicit in the neoliberalism of fear and its authoritarian counterpart, is never completely out of the frame. Table 1: Rejection, repression, and reconciliation Horizons Despite its obvious limitations from the normative point of view of radical or even social democracy, the (re)emergent ideological formation of stakeholder capitalism does, we suggest, represent a relatively coherent attempt at rebuilding ideological consensus in Western societies. After years of intellectual and moral disorganisation, the rise to dominance of stakeholder capitalism among the policy establishment, high finance, some liberal intellectuals, and the financial press perhaps signals the reestablishment of intellectual and ideological discipline among elites. But it seems unlikely that this line of approach will bear fruit in the long run; the dysfunctions of the (neo)liberal world order—spiralling inequality and oligarchy, post-democratic withdrawal and outrage, resurgent nationalism, and anaemic, debt-dependent economic growth—run deep. More immediately, the war in Ukraine, and the unprecedented financial and economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers, threatens to once again reorder the ideological terrain and to intensify the shift away from globalisation. Perhaps the dominant response among (neo)liberal commentators thus far has been to frame the conflict as the first battle in a coming war for the preservation of liberal democracy: we are seeing the return of a more ‘muscular’ liberalism, reminiscent of the early years of the War on Terror.[35] Indeed, throughout modern history, war has served to restore liberalism’s ideological vigour; the conflict in Ukraine may yet prove to be a shot in the arm. [1] P. Stephens, ‘The west is the author of its own weakness’, Financial Times, 30 September 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9779fde6-edc6-4d4c-b532-fc0b9cad4ed9 [2] The Editorial Board, ‘Putin opens a dark new chapter in Europe’, Financial Times, 25 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a69cda07-2f63-4afe-aed1-cbcc51914105 [3] J. Foster and C. el-Ojeili, ‘Centrist Utopianism in Retreat: Ideological Fragmentation after the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 2021. [4][4] Q. Slobodian and D. Plehwe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian, and P. Mirowski (Eds), Nine Lives of Neoliberalism (London: Verso, 2020), p. 3. [5] N. Schiller, ‘A liberalism of fear’, Cultural Anthropology, 27 October 2016, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-liberalism-of-fear [6] W. Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’, New Left Review, 101 (2016), pp. 121-134. [7] W. Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty, and the Logic of Competition, revised edition (London: Sage, 2017). [8] Q. Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018). The reduction of essentially political problems to their economic dimension is a long-standing feature of liberalism as such and is therefore not an original aspect of neoliberalism; it is, however, particularly pronounced in the latter. [9] C. Borio, ‘Central banking in challenging times’, speech at the SUERF Annual Lecture, Milan, 2019. [10] M. Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 151. [11] World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2012 (Geneva: WEF, 2012), pp. 10, 19. [12] B. Cœuré, ‘The political dimension of European economic integration’, speech at the Ligue des droits de l’Homme, Paris, 2013. [13] M. Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What We Have Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 382. [14] William Clinton, ‘President Clinton’s Remarks to the World Economic Forum (2000)’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOq1tIOvSWg [15] Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks, p. 383. [16] T. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises (London: Random House, 2014), p. 209. [17] M. Draghi, ‘Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2017. [18] J-C. Trichet, ‘Central banking in uncertain times – conviction and responsibility’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2010. [19] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times, 28 January 2010. [20] See, for example, Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’. [21] J. Asmussen, ‘Saving the euro’, speech at the Economist's Bellwether Europe Summit, London, 2013. [22] J. Foster, ‘Mission-oriented capitalism’, Counterfutures 11 (2021), pp. 154-166. [23] J. Stiglitz, ‘Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron’, New York Times, 19 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [24] Financial Times, ‘FT sets the agenda with a new brand platform,’ Financial Times, 16 September 2019, https://aboutus.ft.com/press_release/ft-sets-the-agenda-with-new-brand-platform [25] Business Roundtable, ‘Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”’, 19 August 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [26] World Economic Forum, ‘Davos Manifesto 2020: The universal purpose of a company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’, 2 December 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/davos-manifesto-2020-the-universal-purpose-of-a-company-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/ [27] J. Dimon, ‘Annual Report 2018: Chairman and CEO letter to shareholders’, 4 April 2019, https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm?a=1 [28] L. Fink, ‘Larry Fink’s 2022 letter to CEOs: The power of capitalism’, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter [29] See E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984). [30] J. P. Leary, Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018), pp. 162-163. [31] For an early statement, see W. Hutton, The State We’re In (London: Random House, 1995). Freeman also wrote on the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ in the 1990s. It is notable that the drive to develop this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism is made in the absence of, and often disdain for, the key conditions that enabled Western social democracy to (briefly) thrive—namely, a more autarkic global political economy, mass political-party membership, high trade-union density, the ideological threat posed by Soviet communism, a more coherent and engaged public sphere, and stronger civil-society institutions. Further, exponents of stakeholder capitalism retain a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, and so on. For these reasons, we suggest that its closest ideological cousin is the Third Way. [32] B. Cœuré, ‘The consequences of protectionism’, speech at the 29th edition of the workshop ‘The Outlook for the Economy and Finance’, Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 2018. [33] Carney, Value(s), p. 339. [34] D. Gabor, ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52(3) (2021), pp. 429-459. [35] M. Wolf, ‘Putin has reignitied the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy’, Financial Times, 2 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b by Ben Williams

A burgeoning area of political research has focused on how the ideas and practical politics arising from the theories of the ‘New Right’ have had a major impact and legacy not only on a globalised political level, but also in relation to the domestic politics of specific nations. From a British perspective, the New Right’s impact dates from the mid-1970s when Margaret Thatcher became Leader of the Conservative Party (1975), before ascending to the office of Prime Minister in 1979. The New Right essentially rejected the post-war ‘years of consensus’ and advocated a smaller state, lower taxes and greater individual freedoms. On an international dimension, such political developments dovetailed with the emergence of Ronald Reagan as US President, who was elected in late 1980 and formally took office in early 1981. Within this timeframe, there was also associated pro- market, capitalist reforms in countries as diverse as Chile and China. While the ideas of New Right intellectual icons Friedrich von Hayek[1] and Milton Friedman[2] date back to earlier decades of the 20th century and their rejection of central planning and totalitarian rule, until this point in time they had never seen such forceful advocates of their theories in such powerful frontline political roles.

Thatcher and Reagan’s explicit understanding of New Right theory was variable, but they nevertheless successively emerged as two political titans aligned by their committed free-market beliefs and ideology, forming a dominant partnership in world politics throughout the 1980s. Consequently, the Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ that had traditionally incorporated shared cultural values and military and security co-operation, reached new heights amidst a decade very much dominated by New Right ideology. However, as we now look back over forty years on, debate has arisen as to what extent the ideas and values of the New Right are still relevant in the context of more contemporary political events, namely in relation to how the free market can appropriately react to major global crises. This has been notably applied to how various governments have reacted to both the 2007–8 global economic crash and the ongoing global Covid-19 pandemic, where significant levels of state intervention have challenged conventional New Right orthodoxies that ‘the free market knows best’. The New Right’s effect on British politics (1979-97) In my doctoral research into the evolution of contemporary Conservative Party social policy, the legacy and impact of the New Right on British politics formed a pivotal strand of the thesis, specifically how the UK Conservative Party sought to evolve both its image and policy agenda from the New Right’s free market economic emphasis into a more socially oriented direction. [3] Yet my research focus began at the tail end of the New Right’s period of hegemony, in the aftermath of the Conservative Party’s most devastating and humiliating electoral defeat for almost 100 years at the 1997 general election.[4] From this perspective of hindsight that looked back on eighteen years of continuous Conservative rule, the New Right’s influence had ultimately been a source of both rejuvenation and decline in relation to Conservative Party fortunes at different points of the electoral and historical cycle. In a positive sense, in the 1970s it appeared to revitalise the Conservative Party’s prospects while in opposition under the new leadership of Thatcher, and instilled a flurry of innovative, radical and eye-catching policies into its successful 1979 manifesto, which in subsequent years would be described as reflecting ‘popular capitalism’. Such policies would form the basis of the party’s accession to national office and consequent period of hegemonic rule throughout the 1980s in particular. The nature of such party-political hegemony as a conceptual term has been both analysed and explained in terms of its rise and fall by Andrew Gamble among others, who identified various core values that the Conservatives had traditionally stood for, namely ‘the defence of the Union, the defence of the Empire, the defence of the Constitution, and the defence of property’[5]. However, in a negative sense, by the mid to late 1990s, as Gamble identifies, the party appeared to have lost its way and had entered something of a post-Thatcher identity crisis, with the ideological dynamic instilled by the New Right’s legacy fatally undermining its previously stable equilibrium and eroding the traditional ‘pillars’ of hegemony’ as identified above. While Thatcher’s successor John Major was inclined to a more social as opposed to economic policy emphasis and between 1990-97 sought to distance himself from some of her harsher ideological policy positions, it was perhaps the case that the damage to the party’s electoral prospects had already been done. Not only had the Conservatives defied electoral gravity and won a fourth successive term in office in 1992, but the party’s broader ethos appeared to have become distorted by New Right ideology, and it became increasingly detached from its traditional instincts for pragmatic moderation located at the political centre, and notably its capacity to read the mood with regards the British public’s instinctive tendencies towards social conservatism, as has been argued by Oakeshott in particular. [6] Critics also commented that the New Right’s often harsh economic emphasis was out of touch with a more compassionate public opinion that was emerging in wider public polling by the mid-1990s, and which expressed increasing concerns for the condition of core public services. This was specifically evident in documented evidence that between ‘1995-2007 opinion polls identified health care as one of the top issues for voters.[7] The New Right’s focus on retrenchment and the free market was now blamed for creating such negative conditions by some, both within and outside the Conservative Party. Coupled with a steady process of Labour Party moderation over the late 1980s and 1990s, such trends culminated in major and repeated electoral losses inflicted on the Conservative Party between 1997 and 2005 (with an unprecedented three general election defeats in succession and thirteen years out of government). The shifting spectrum and New Labour When once asked what her greatest political achievement was, Margaret Thatcher did not highlight her three electoral victories but mischievously responded by pointing to “Tony Blair and New Labour”. It is certainly the case that Blair’s premiership from 1997 onwards was very different from previous Labour governments of the 1960s and 1970s, and arguably bore the imprint of Thatcherism far more than any traces of socialist doctrine. This would strongly suggest that the impact and legacy of the New Right went far beyond the end of Conservative rule and continued to wield influence into the new century, despite the Conservative Party being banished from national office. This was evident by the fact that Blair’s Labour government pledged to “govern as New Labour”, which in practice entailed moderate politics that explicitly rejected past socialist doctrines, and by adhering to the political framework and narrative established during the Thatcher period of New Right hegemony. This included an acceptance of the privatisation of former state-owned industries, tougher restrictions to trade union powers, markedly reduced levels of government spending and direct taxation, and overall, far less state intervention in comparison to the ‘years of consensus’ that existed between approximately 1945-75 (shaped by the crisis experience of World War Two). Most of these policies had been strongly opposed by Labour during the 1980s, but under New Labour they were now pragmatically accepted (for largely electoral and strategic purposes). Blair and his Chancellor Gordon Brown tinkered around the edges with some progressive social reforms and there were steadily growing levels of tax and spend in his later phase in office, but not on the scale of the past, and the New Right neoliberal ‘settlement’ remained largely intact throughout thirteen years of Labour in office. Indeed, Labour’s truly radical changes were primarily at constitutional level; featuring policies such as devolution, judicial reform (introduction of the Supreme Court), various parliamentary reforms (House of Lords), Freedom of Information legislation, as well as key institutional changes such as Bank of England independence. The nature of this reforming policy agenda could be seen to reflect the reality that following the New Right’s ideological and political victories of the 1980s, New Labour had to look away from welfarism and political economy for its major priorities. Conservative modernisation (1997 onwards) Given the electoral success of Tony Blair and New Labour from 1997 onwards, the obvious challenge for the Conservatives was how to respond and readjust to unusual and indeed unprecedented circumstances. Historically referred to as ‘the natural party of government’, being out of power for a long time was a situation the Conservatives were not used to. However, from the late 1990s onwards, party modernisers broadly concluded that it would be a long haul back, and that to return to government the party would have to sacrifice some, and perhaps all, of its increasingly unpopular New Right political baggage. This determinedly realistic mood was strengthened by a second successive landslide defeat to Blair in 2001, and a further—albeit less resounding—defeat in 2005. Key and emerging figures in this ‘modernising’ and ‘progressive’ wing of the party included David Cameron, George Osborne and Theresa May, none of whom had been MPs prior to 1997 (i.e., crucially, they had no explicit connections to the era of New Right hegemony) and all of whom would take on senior governmental roles after 2010. Such modernisers accepted that the party required a radical overhaul in terms of both image and policy-making, and in global terms were buoyed by the victory of ‘compassionate’ conservative George W. Bush in the US presidential election in late 2000. Consequently, ‘Compassionate Conservatism’ became an increasingly used term among such advocates of a new style of Conservative policy-making (see Norman & Ganesh, 2006).[8] My doctoral thesis analysed in some depth precisely what the post-1997 British Conservative Party did in relation to various policy fronts connected to this ‘compassionate’ theme, most notably initiating a revived interest in the evolution of innovative social policy such as free schools, NHS reform, and the concept of ‘The Big Society’. This was in response to both external criticism and self-reflection that such policy emphasis and focus had been frequently neglected during the party’s eighteen years in office between 1979 and 1997.[9] Yet the New Right legacy continued to haunt the party’s identity, with many Thatcher loyalists reluctant to let go of it, despite feedback from the likes of party donor Lord Ashcroft (2005)[10] that ‘modernisation’ and acceptance of New Labour’s social liberalism and social policy investment were required if the party was to make electoral progress, while ultimately being willing to move on from the (albeit triumphant) past. Overview of The New Right and post-2008 events: (1) The global crash (2) austerity (3) Brexit (4) the pandemic During the past few decades of British and indeed global politics, the New Right’s core principles of the small state and limited government intervention have remained clearly in evidence, with its influence at its peak and most firmly entrenched in various western governments during the 1980s and 90s. However, within the more contemporary era, this legacy has been fundamentally rocked and challenged by two major episodes in particular, namely the economic crash of 2007–8, and more recently the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Both of these crises have featured a fundamental rebuke to the New Right’s established solutions as aligned with the culture of the reduced state, as had been cemented in the psyche of governance and statecraft within both Britain and the USA for several decades. In the context of the global economic slump, the immediate and instinctive reaction of Brown’s Labour government in Britain and Barack Obama’s Democrat administration in the USA was to focus on a primary role for the state to intervene and stimulate economic recovery, which entailed that large-scale ‘Keynesian’ government activity made a marked comeback as the preferred means of tackling it. While both such politicians were less ideologically wedded to the New Right pedigree (since they were attached to parties traditionally more of the liberal left), this scenario nevertheless marked a significant crossroads for the New Right’s legacy for global politics. However, once the dust had settled and the economic situation began to stabilise, the post-2010 austerity agenda that emerged in the UK (as a longer-term response to managing the global crash) provided New Right advocates with an opportunistic chance to reassert its former hegemony, given the setback to its influence in the immediate aftermath of 2008. Although Prime Minister David Cameron rejected criticism that austerity marked a reversion to harsh Thatcherite economics, having repeatedly distanced himself from the former Conservative Prime Minister since becoming party leader in 2005, there were certainly similarities in the emphasis on ‘balancing the books’ and reducing the size of government between 2010-15. Cameron argued this was not merely history repeating itself, and sought to distinctively identify himself as a more socially-oriented conservative who embraced an explicit social conscience that differed from the New Right’s primarily economic focus, as evident in his ‘Big Society’ narrative entailing a reduced state and more localised devolution and voluntarism (yet which failed to make his desired impact).[11] Cameron argued that “there was such a thing as society” (unlike Thatcher’s quote from 1987)[12], yet it was “not the same as the state”. [13] Following Cameron’s departure as Prime Minister in 2016, the issue that brought him down, Brexit, could also be viewed from the New Right perspective as a desirable attempt to reduce, or ideally remove, the regulatory powers of a European dimension of state intervention, with the often suggested aspiration of post-Brexit Britain becoming a “Singapore-on-Thames” that would attract increased international capital investment due to lower taxes, reduced regulations and streamlined bureaucracy. It was perhaps no coincidence that many of the most ardent supporters of Brexit were also those most loyal to the Thatcher policy legacy that lingered on from the 1980s, representing a clear ideological overlap and inter-connection between domestic and foreign policy issues.[14] On this premise, the New Right’s influence dating from its most hegemonic decade of the 1980s certainly remained. However, from a UK perspective at least, the Covid-19 pandemic arguably ‘heralded the further relative demise of New Right influence after its sustained period of hegemonic ascendancy’.[15] This is because, in a similar vein to the 2007–8 economic crash, the reflexive response to the global pandemic from Boris Johnson’s Conservative government in the UK and indeed other western states (including the USA), was a primarily a ‘statist’ one. This was evidently the preferred governmental option in terms of tackling major emergencies in the spheres of both the economy and public health, and was perhaps arguably the only logical and practical response available in the context of requiring such co-ordination at both a national and international level, which the free market simply cannot provide to the same extent. Having said that, during the pandemic there was evidence of some familiar neoliberal ‘public-private partnership’ approaches in the subcontracting-out of (e.g.) mask and PPE production, lateral flow tests, vaccine research and production, testing, or app creation, which suggests Johnson’s administration sought to put some degree of business capacity at the heart of their policy response. Nevertheless, the revived interventionist role for the state will possibly be difficult to reverse once the crisis has subsided, just as was the case in the aftermath of World War Two. Whether this subsequently creates a new variant of state-driven consensus politics (as per the UK 1945-75) remains to be seen, but in the wake of various key political events there is clear evidence that the New Right’s legacy, while never being eradicated, certainly seems to have been diluted as the world progresses into the 2020s. How the post-pandemic era will evolve remains uncertain, and in their policy agendas various national governments will seek to balance both the role of the state and the input of private finance and free market imperatives. The nature of the balance remains a matter of speculation and conjecture until we move into a more certain and stable period, yet it would be foolish to write off the influence of the New Right and its resilient legacy completely. [1] Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, (1944) [2] Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, (1962) [3] Ben Williams, The Evolution of Conservative Party Social Policy, (2015) [4] BBC ON THIS DAY | 2 | 1997: Labour routs Tories in historic election (2nd May 1997) [5] Andrew Gamble, The Crisis of Conservatism, New Left Review, (I/214, November–December 1995) [6] Michael Oakeshott, On Human Conduct, (1975) [7] Rob Baggott, ‘Conservative health policy: change, continuity and policy influence’, cited in Hugh Bochel (ed.), The Conservative Party and Social Policy, (2011), Ch.5, p.77 [8] Jesse Norman & Janan Ganesh, Compassionate conservatism- What it is, why we need it (2006), https://www.policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/compassionate-conservatism-june-06.pdf [9] Ben Williams, Warm words or real change? Examining the evolution of Conservative Party social policy since 1997 (PhD thesis, University of Liverpool), https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/11633/1/WilliamsBen_Apr2013_11633.pdf [10] Michael A. Ashcroft, Smell the coffee: A wake-up call for the Conservative Party, (2005) [11] Ben Williams, The Big Society: Ten Years On, Political Insight, Volume: 10 issue: 4, page(s) 22-25 (2019) [12] Margaret Thatcher, interview with ‘Woman’s Own Magazine’, published 31 October 1987. Source: Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689 [13] Society and the Conservative Party - BBC News (9th January 2017) [14] Ben Williams, Brexit: The Links Between Domestic and Foreign Policy, Political Insight, Volume: 9 issue: 2, page(s): 36-39 (2018) [15] Ben Williams, The ‘New Right’ and its legacy for British conservatism, Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021) 29/3/2021 Neoliberalism against world government? The neglected world order dimension in ideologiesRead Now by Stefan Pedersen

The idea that adherents of neoliberalism desire world government is an old misunderstanding. In recent years this mistaken notion has been promoted by populists such as former President Donald Trump who in one of his most ideology and world order oriented speeches to the UN General Assembly made the ‘ideology of globalism’ and global governance seem diametrically opposed to his preferred ‘doctrine of patriotism’ and national sovereignty.

Though it is not nominally a given that Trump and others with similar nationalist inclinations are specifically talking about neoliberalism when this supposed major contemporary ideological cleavage comes up, there should be little doubt among students of global governance that this is effectively what is being claimed when neoliberalism has been the hegemonic ideology in global governance circles at least since the Cold War ended.[1] In addition, the terms ‘globalism’ and ‘globalists’ have been connected to early and present-day neoliberals in several influential studies over the last few decades. Noteworthy examples in this regard are here initially Manfred B. Steger’s many works treating neoliberalism as the hegemonic form of ‘globalism’—albeit not the only one.[2] Then, Or Rosenboim notes how neoliberal theorists actively played a role in ‘the emergence of globalism’ in the 1930s and 1940s—and she also sees neoliberalism as one of several streams of thought advocating ‘globalism’ in the sense of variations over the theme of establishing some kind of global order.[3] Finally, and most consequentially for the way neoliberalism is presently understood, Quinn Slobodian has in his Globalists (2018) convincingly and in detail argued that the early neoliberals operated with an agenda aiming for global control of the workings of the world economy that subsequent ideological fellow travellers had to a certain extent managed to establish through legislative and international institutional inroads by the mid-1990s.[4] Those at the forefront of studying neoliberalism today, such as Slobodian, has provided us with a multitude of insights into neoliberalism’s multifaceted development and present configuration. For instance by further confirming how the neoliberals have prioritised establishing ‘world law’ over a ‘world state’.[5] But on one front there seems to be a paucity in the record—and that is when it comes to how the neoliberals originally arrived at this stance and what it actually meant in world order terms in comparison to the then extant alternatives. What most scholars have thought happened in world order terms during neoliberalism’s formative period has had a tendency to be derived from an intense scrutiny of the period that spanned from the Colloque Walter Lippmann in 1938 to the foundation of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in 1947. Significant here is what was said by the various ‘early neoliberals’ who attended these monumental events in this formative period for the neoliberal ideology.[6] But as Hagen Schulz-Forberg has now sensibly argued, if the Colloque Walter Lippmann represents the birth of neoliberalism, then that birth will have been ‘preceded by pregnancy’.[7] The years of importance for the earliest development of neoliberal thought does therefore not exclusively include the 1938–1947 period but also the about two decades of intellectual gestation that preceded that final sprint leading up to the formation of the MPS. Considering the span of the careers of some of the primary actors here, such as Walter Lippmann—who the eponymous Colloque in 1938 was held in honour of—and Ludwig von Mises, this brings us back to their earlier writings during the First World War. We can therefore say that the neoliberalism whose core tenets were broadly agreed upon in the late 1940s was the fruit of debates that spanned the entire period 1914 to 1947. This was also a time when considerable intellectual effort was put into thinking about world order, first concerning the shape of the League of Nations and then the shape of what ought to replace the League of Nations once this organisation had revealed itself to be dysfunctional for ensuring peace among mankind.[8] World politically, the temporal span from 1914 to 1947 also takes us from the realisation that imperialist nationalism needs to be tamed or excised, brought first to the fore by the occurrence of the Great War itself, to the understanding that a ‘Cold War’ had begun in 1947—an expression not coincidentally popularised by Lippmann, who was a journalist and an avid commentator on foreign affairs, and in 1947 published a book with the title The Cold War that was a compilation of articles he had recently written.[9] Lippmann, as perhaps the premier American foreign policy commentator of the time and associate of centrally placed early neoliberals such as Friedrich von Hayek, is the key to unlocking the world order dimension that neoliberalism ended up incorporating by the end of the 1940s. The world order dimension To get a handle on this argument it is important to note that neoliberalism, like all other major political ideologies, can be understood as composed of a series of conceptual dimensions. Since neoliberalism is considered the ideology behind the process of economic globalisation that gained truly global reach once the Cold War ended, it is naturally its economic dimension that has been the key focus. And to understand how this works, we can think of the number of ideologies with party political representation that by the 1990s had put neoliberalism’s economic dimension into the economic slot Keynesianism once occupied. This practically happened across the board, with Thatcher and the Conservatives and Reagan and the Republicans spearheading a change in policy later also followed up by Clinton and the Democrats and Blair and the Labour Party—and this was repeated throughout the world. Thinking here in terms of an ideally articulated neoliberalism, rather than the compromised versions that appear once the ideology is made to fit some party political program in the real world of political practice, neoliberalism should be understood as a multi-dimensional ideology in its own right that also contains a ‘world order dimension’ of great significance. Every ideology contains what is at least an implicit world order dimension. But since today’s nation-state centric world order has existed unchallenged longer than most can remember, it is commonly assumed that all political ideologies are designed to function in the state system. Conservatism, liberalism, and socialism, we know best in their national garb. Stalinism is a form of communism made to suit the world of nation-states with its focus on achieving ‘socialism in one country’. Every ideology that is made to function within the nationalist and statist parameters of the current world order share the same basic ‘world order dimension’. The early neoliberals ended up deviating from traditional nationalist conceptions while recognising—with Marx and Trotsky—that a world economy had become a feature of reality. The Trotskyist solution to dealing with a novel world economy was to aim to subsume the entire world under the command and control of a communist regime that would also lead politically. The neoliberals worked from the same premise, that there was now a world economy, but with a different set of aims. They wanted to free the economy—meaning those who benefitted from mastering it through their entrepreneurial skills. That meant avoiding at all cost that some force powerful enough to subsume the world economy to a different set of political interests arose—be they for instance communist, democratic socialist, social liberal, or humanist (and in our day we can add ‘ecological’ to that list). This was in part achieved through taking a strong anti-totalitarian stance, deriding both fascism and communism. But there was a greater Westernised threat to a world order suited to neoliberal interests: a world democracy, where the free people of the world could elect a socialist world party into power. A world democracy, as someone as versed in cosmopolitan theory as Mises well knew, was not really compatible with a world of nation-states. It would have to involve what we can call a ‘cosmopolitan world order dimension’ that is incompatible with the nation-state sovereignty that forms the foundation of the extant system of states. Mises had once thought this an ideal solution himself, since to him cosmopolitanism was compatible with ‘liberalism’ and ensuring world peace. But it gradually dawned on both Mises and Hayek that a paradigm shift in the world order dimension subscribed to by the democratic populations on the planet could spell doom for the institution of the neoliberal economic agenda they were in the process of planning in detail. A world government, though still desirable if its only function would be to ensure the free working of the world economy, was an all too risky proposition if it were to be democratically elected. The simple reason for this was that the neoliberal agenda was understood to be not inherently popular but elitist, or for the few rather than the many. Popular politics in the 1930s and 1940s, especially as fascism, Nazism, isolationism, and other right-wing varieties lost their pull, was becoming more and more social democratic or liberal[10] in a manner that we today would perhaps better recognise as ‘democratic socialist’. The neoliberals therefore thought it would be better if the rules for running the world economy were simply made expertly and separated from the political rules that parties elected into power could alter according to the volatile demands of diverse voting publics. This neat separation would have the benefit of blocking socialist reforms from having severe world economic effects even if socialists were to be elected into power in key nation-states. What this meant in world order terms was that neoliberalism needed to be both economically ‘globalist’ or universalist, so that the world economy could operate on neoliberal principles, and politically nationalist, so that controlling the world economy as a whole would not be subject to popular desires. The possibility of just such a separation was aired by Mises already in 1919.[11] But due to the insecurity surrounding the question of what would replace the ailing League of Nations, a question which became steadily more acute as world politics converged on the course that led to World War II throughout the 1930s, there was always also the chance that the masses would start to demand the more comprehensive political solution to the world’s problems that world federalism offered. The neoliberals therefore also had to address this contingency—while finding ways to argue against it without sounding too illiberal. However, as the Second World War entered the phase where Allied victory seemed certain while its leaders seemed eager to water down any plans for a permanent organisation to keep the peace, the neoliberals understood that the old plans could be reinstated. Lippmann is an apt example of a neoliberal theorist who helped see to it that things developed this way. Walter Lippmann's crusade against One Worldism Lippmann had a long history of engagement with issues relating to diplomacy and grand strategy that made him the foreign policy wonk in the group of early neoliberals. In 1918, Lippmann had been the brain behind no less than eight of Wilson’s historic ‘Fourteen Points’ that laid down the American terms for the peace to come after the end of the First World War.[12] From this time on, Lippmann was a very well-connected American journalist and intellectual, whose close connections in Washington D.C. included all sitting Presidents from Wilson to Lyndon B. Johnson.[13] Even after his formal retirement from the Washington D. C. circuit, Nixon sought the old Lippmann’s advice too.[14] Lippmann was no neutral observer, and is for instance known to have sided for Harry Truman against Henry A. Wallace in the crucial contest for the Vice Presidency that preceded President Roosevelt’s last nomination.[15] This calculated action is evidence that Lippmann, in accordance with early neoliberal tenets, preferred Truman’s anti-progressive agenda of replacing the ‘New Dealers’ Roosevelt had earlier put in place—New Dealers such as Wallace—with ‘Wall Streeters’ in his cabinet.[16] What is less often pointed out here is that Lippmann, through favouring Truman over Wallace, also would have made it clear that he was siding against the ‘One Worldism’ that Wallace and others who had thought long and hard about a desirable world order advocated.[17] Lippmann, who instead appealed to a ‘realism’ that rested ‘on a hard calculation of the “national interest”’ was at this point ‘distressed by’ the ‘one world euphoria’ which was then a prevalent feature of post-war planning in idealist circles.[18] The world federalism that was espoused by the idealists of the day seemed entirely impractical to Lippmann, who himself can be counted amongst the ‘classical realists’ in international relations theory—even if his ‘original contributions to realist theory were ultimately modest’.[19] In contrast, Lippmann towards the end of World War II instead offered up a ‘formula for great-power cooperation’ that he thought of as ‘a realistic alternative both to bankrupt isolationism and wishful universalism’.[20] What all this goes to show is that Lippmann, in his capacity within early neoliberal circles as an authority on matters of foreign policy and world order, would have further strengthened the neoliberal insight that the state-system was crucial to neoliberalism. Reading the contemporaneous works of Mises and Hayek—which in the case of Mises spans nearly the entire 1914–1947 period—this is indeed what seems to have happened towards the end of this formative era for neoliberalism. Mises and Hayek were both markedly more open to idealist forms of world federalism in the early to late 1930s than what they ended up being towards the end of the war and in the late 1940s.[21] This was likely part in response to Lippmann’s realist influence, supported by the general course of events, with the founding of the United Nations and the early signs of the Cold War developing, and part in response to a growing realisation that the world order that was most desirable from a neoliberal standpoint ought to be ‘many worldist’ in its construction rather than based on genuine One Worldism. Mises and Hayek stands out as the most centrally placed early neoliberals who were willing to engage with the world order debate that ran concurrently to the formative neoliberal debate. Lippmann was not the only early neoliberal sceptical to One Worldism—the claim has indeed been made that the early neoliberals taken under one were all ‘acutely aware that nation-states were here to stay’.[22] But in the world order discourse of the time, there were two distinctly different approaches to what was then viewed as the desirable and necessary goal of creating ‘a world-wide legal order’—and these two were either ‘law-by-compact-of-nations’ or a ‘complete world government that will include and sanction a world-wide legal order’.[23] It is debateable if even those who subscribed to the former approach really believed that ‘nation-states were here to stay’ as the League of Nations order wound up around them and the Third Reich and then Imperial Japan swallowed most nations in their surrounding areas. It was also not a certainty that the United States or the Soviet Union, who each straddled the globe from the perspective of their respective capitals at war’s end, would let go of the new lands they now commanded. For a while, both Mises and Hayek supported some form or other of world federalism to ensure that basic security could be installed worldwide—with Mises advocating world government and Hayek favouring a federation of capitalist nations.[24] What laid the dreams of a world order for all humanity to rest was the lack of trust among the Allied nations that established the United Nations in 1945—which led to veto power being granted to the permanent members of the Security Council. This effectively made humanity’s further progress hostage to the whims of the leaders of the nations that won World War II, here primarily the conflicting interests of the new superpowers. Any remnant of hope for a quick remedy to this stalemate then disappeared completely as the Cold War started to escalate and the McCarthyite Red Scare kicked in. This made cosmopolitan advocates of a humane world order appear dangerously close to proponents of Internationalism in the United States and conversely led their Soviet equivalents to be seen as potential capitalist class-traitors there.[25] The neoliberals had before this crisis point was reached and the world order debate was ended in its present iteration already disowned their prior engagement with figuring out what form a desirable world order people would willingly sign up to should take. Divide et impera Sometime between the beginning of the Second World War in Europe in 1939 and its end in 1945, both Hayek and Mises seem to have come to the same conclusion—supported by Lippmann’s insights and arguments—that world government would more likely than not be anathema to the primary goal of neoliberalism: creating a world economy where entrepreneurs could let their fortunes bloom unimpeded by negative government intervention. The reason for this was straightforward enough. Any world federation that in principle would be acceptable to the Western nations, first and foremost in 1945 the United States, Britain, and France, would have to be democratic. And an elected world government would at this time more likely than not be socialist, eager to install a Keynesian version of a global New Deal. This represented the worst of all worlds for the neoliberals—the least desirable scenario. One Worldism therefore had to be countered—with Lippmann’s ‘realism’ and communist smears. Subsequently, the whole program for a world government had to be kept discredited—which is achieved simply enough by letting the present world order run on auto-pilot, since its political default position is to uphold national sovereignty, nationalism, and the division of humanity into a myriad of designated national peoples with their own territorial states. We are in the end faced with a peculiar world order dimension in neoliberalism that is anti-globalist in political terms but globalist in economic terms—insofar as we understand ‘globalist’ to be a synonym for universalist, which is of course how it is understood by nationalist politicians today who use the term to convey the opposite of the nationalism they themselves seek to promote. The paradox is therefore that the neoliberal ‘globalists’ are against the creation of a democratically functioning planetary polity or world government, especially if one understands ‘world government’ to be the legitimate government of a world republic or planetary federation ruled by representatives elected into power by the global populace in free and fair elections—that therefore also would end up being multi-ideological. Pluralist cosmopolitan democracy embodied in a world parliament is not the goal, or even one of the goals that adherents of neoliberalism aim for. Instead it is something neoliberals fear, and that is a very different proposition from the nationalists’ misconceived portrayal. Another great misunderstanding today, one that follows from the misconception that the neoliberals want genuine world government, is that the neoliberals would abhor nationalism. Today, this leads many on both the left and right to think that neoliberalism can be effectively countered with a turn to nationalism—on the assumption that nationalism is the opposite of neoliberal globalism and therefore incompatible with it. But that is not the case. The neoliberals instead rely on nationalism to keep democracy tamed and irrelevant, at a scale too small for it to exercise effective control over the world economy’s neoliberal ruleset—which continues to send the spoils of economic activity towards Hayek’s idealised ‘entrepreneurs’. Global democracy, stripped of nationalist division, is what the early neoliberals truly feared. We can today imagine what for instance a democratic socialist world government able and willing to enforce global taxation could do to the profit margins of high finance, multi-national corporations, global extractive industries, and the high net worth of individuals that currently are allowed to keep their money outside of democratic reach in offshore accounts, and see why the prospect of an elected world government became repulsive to neoliberals. The big question today is therefore, when will we see an ideological movement for instituting exactly the kind of world government in the interest of humanity in general that would work properly to counter the neoliberal agenda? Any number of ideological projects could be global in scope, whether we are talking about prioritising liberal global democracy, economic solidarity, the ecological preservation of the biosphere, or enabling the future flourishing of human civilisation through intertwining all these three ideological strands into a cohesive and holistic planetary cosmopolitanism or planetarism that would be both post-nationalistic and post-neoliberal in principle. The left and green parties of today are clearly not there yet—but they will at some point have to realise that neoliberalism and nationalism are two sides of the same coin—the two ideologies reinforce each other and should therefore be countered as one. [1] Stephen Gill. ‘European Governance and New Constitutionalism: Economic and Monetary Union and Alternatives to Disciplinary Neoliberalism in Europe’, New Political Economy, 3 (1), 1998, pp. 5–26. [2] Manfred B. Steger. Globalisms: The Great Ideological Struggle of the Twenty-First Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009. [3] Or Rosenboim. The Emergence of Globalism. Visions of World Order in Britain and the United States, 1939-1950. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017. [4] Quinn Slobodian. Globalists. The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018. [5] Slobodian. Ibid., p. 272. [6] See for instance: Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds. The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009. [7] Hagen Schulz-Forberg. ‘Embedded Early Neoliberalism: Transnational Origins of the Agenda of Liberalism Reconsidered’, in Dieter Plehwe, Quinn Slobodian and Philip Mirowski, eds. Nine Lives of Neoliberalism. London: Verso, pp. 169-196. [8] Glenda Sluga. Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. [9] Ronald Steel. Walter Lippmann and the American Century. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1980, p. 445. [10] ‘Liberal’ in the American sense of supporting (the left-wing of) the Democratic party. [11] Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy: Contributions to the Politics and History of Our Time. New York: New York University Press, 1983. [12] Steel, Ibid., pp. 134–135. [13] Steel, Ibid. [14] Steel, Ibid., p. 589. [15] John C. Culver and John Hyde. American Dreamer. A Life of Henry A. Wallace. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, p. 342. [16] John Nichols. The Fight for the Soul of the Democratic Party. The Enduring Legacy of Henry A. Wallace’s Antifascist, Antiracist Politics. London: Verso, 2020, pp. 109–110. [17] Culver and Hyde, Ibid., pp. 402–418; and; Steel, Ibid., p. 407. [18] Steel, Ibid., pp. 404–406. [19] William E. Scheuerman. The Realist Case for Global Reform. Cambridge: Polity, 2011, p. 6. [20] Steel, Ibid., p. 406. [21] This development is detailed in the article that this text is a companion piece to. [22] Schulz-Forberg, Ibid., p. 194. [23] Gray L. Dorsey. ‘Two Objective Bases for a World-Wide Legal Order’, in F.S.C Northrop, ed. Ideological Differences and World Order. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949, pp. 442–474. [24] Also detailed in the article that this text is a companion piece to. [25] Gilbert Jonas. One Shining Moment: A Short History of the American Student World Federalist Movement 1942-1953. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse.com, Inc. 2001. by Regina Queiroz

Although ‘neoliberalism’ means different things to different people, I follow those, who, like Michael Freeden, view neoliberalism as an ideology, i.e., ‘a wide-ranging structural arrangement that attributes decontested meaning to a range of mutually defining political concepts’.[1] In this approach, neoliberalism relies on a libertarian conception of both the individual and liberty. Even if not all decontestations of what “libertarian” is meant to denote have made it into neoliberalism (e.g., libertarian socialisms, or even a fair number of anarcho-libertarianisms), libertarian views on individuals and liberty provide a particular interpretation of its core values: individualism, liberty, law, laissez-faire governance, and market states.[2]