by Marius S. Ostrowski

In May 2021, the British broadcaster ITV launched a new advertising campaign to showcase the range of content available on its streaming platform ITV Hub. In a series of shorts, stars from the worlds of drama and reality TV go head-to-head in a number of outlandish confrontations, with one or the other (or neither) ultimately coming out on top. One short sees Jason Watkins (Des, McDonald & Dodds) try to slip Kem Cetinay (Love Island) a glass of poison, only for Kem to outwit him by switching glasses when Jason’s back is turned. Another has Katherine Kelly (Innocent, Liar) making herself a gin and tonic, opening a cupboard in her kitchen to shush a bound and gagged Pete Wicks (The Only Way is Essex). A third features Ferne McCann (I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, The Only Way is Essex) rudely interrupting Richie Campbell (Grace, Liar) in the middle of a crucial phonecall by raining bullets down on him from a helicopter gunship. And the last, most recent advert shows Olivia Attwood (Love Island) and Bradley Dack (Blackburn Rovers) distracted mid-walk by an adorable dog, only to have a hefty skip dropped on them by Anna Friel (Butterfly, Marcella).

The message of all these unlikely pairings is clear. In this age of binge-watching, lockdowns, and working from home, ITV is stepping up to the plate to give us, the viewers, the very best in premium, popular, top-rated televisual content to satisfy every conceivable taste. Against the decades-long rise of subscription video-on-demand streaming, one of the old guard of terrestrial television is going on the offensive. Netflix? Prime? Disney+? Doesn’t have the range. Get you a platform that can do both. (BAFTA-winning drama and Ofcom-baiting reality, that is.) More a half-baked fighting retreat than an all-out assault? Think again; ITV is “stopping at nothing in the fight for your attention”. Can ITV really keep pace with the bottomless pockets of the new media behemoths? Of course it can. Even without a wealth of resources you can still have a wealth of choice. The eye-catching tagline for all this: “More drama and reality than ever before.” In this titanic struggle between drama and reality, the central irony—or, perhaps, its guilty secret—is how often the two sides of this dichotomy fundamentally converge. The drama in question only very rarely crosses the threshold into true fantasy, whether imagined more as lurid science-fiction or mind-bending Lovecraftian horror; meanwhile, reality is several stages removed from anything as deadening or banal as actual raw footage from live CCTV. Instead, the dramas that ITV touts as its most successful examples of the genre pride themselves on their “grittiness”, “believability”, and even “realism”. At the same time, the “biggest” reality shows are transparently “scripted” and reliant on “set-ups” and other manipulations by interventionist producers, and the highest accolade their participants can bestow on one another is how “unreal” they look. Both converge from different sides on an equilibrium point of simulated, real-world-dramatising “hyperreality”; and as we watch, we are unconsciously invited to ask where drama ends and where reality begins. In our consumption of drama and reality, we are likewise invited to “pick our own” hyperreality from the plethora of options on offer. The sheer quantity of content available across all these platforms is little short of overwhelming, and staying up-to-date with all of it is a more-than-full-time occupation. Small wonder, then, that we commonly experience this “wealth of choice” as decision “fatigue” or “paralysis”, and spend almost as much if not often more time scrolling through the seemingly infinite menus on different streaming services than we do actually watching what they show us. But the choices we make are more significant than they might at first appear. The hyperrealities we choose determine how we frame and understand both the world “out there” within and beyond our everyday experiences and the stories we invent to describe its horizons of alternative possibility. They decide what we think is (or is not) actually the case, what should (or should not) be the case, what does (and does not) matter. Through our choice of hyperreality, we determine how we wish both reality and drama to be (and not to be). Given the quantity of content available, the choice we make is also close to zero-sum. As the “fight for our attention” trumpeted by ITV implies, our attention (our viewing time and energy, our emotional and cognitive engagement) is a scarce resource. Even for the most dedicated bingers, picking one or even a few of these hyperrealities to immerse ourselves in sooner or later comes at the cost of being able to choose (at least most of) the others. We have to choose whether our preferred hyperreality is dominated by “glamorous singles” acting out all the toxic and benign microdynamics of heterosexual attraction, or the murky world of “bent coppers” and the rugged band of flawed-but-honourable detectives out to expose them; whether it smothers us in parasols and petticoats, and all the mannered paraphernalia of period nostalgia, or draws us into the hidden intricacies of a desperately-endangered natural world. In short, we have to choose what it is about the world that we want to see. * * * We face the same overload of reality and drama, and the same forced choice, when we engage with the more direct mediatised processes that provide us with information about the world around us. Through physical, online, and social media, we are met with a ceaseless barrage of new, drip-fed, self-contained events and phenomena, delivered to us as bitesize nuggets of “content”. Before, we had the screaming capitalised headlines and one-sentence paragraphs of the tabloid press. Now, we also have Tweets (and briefly Fleets), Instagram stories and reels, and TikTok videos generated by “new media” organisations, “influencers” and “blue ticks”, and a vast swarm of anonymous or pseudonymous “content providers”. All in all, the number of sources—and the quantity of output from each of these sources—has risen well beyond our capacity to retain an even remotely synoptic view of “everything that is going on”. Of course, it is by now a well-rehearsed trope that these bits of “news” and “novelty” content leave no room for nuance, granularity, and subtlety in capturing the complexities of these events and phenomena. But what is less-noticed are the challenges they create for our capacity to make meaningful sense of them at all from our own (individual or shared) ideological stances. Normally, we gather up all the relevant informational cues we can, then—as John Zaller puts it—“marry” them to our pre-existing ideological values and attitudes, and form what Walter Lippmann calls a “picture inside our heads” about the world, which acts as the basis for all our subsequent thought and action.[1] But the more bits of information we are forced to make sense of, and the faster we have to make sense of them “in live time” as we receive them—before we can be sure about what information is available instead or overall—the more our task becomes one of information-management. We are preoccupied with finding ways to get a handle on information and compressing it so that our resulting mental pictures of the world are still tolerably coherent—and so that our chosen hyperreality still “works” without too many glitches in the Matrix. These processes of information-management are far from ideologically neutral. As consumers of information, our attention is not just passive, there to be “fought over” and “grabbed”; rather, we actively direct it on the basis of our own internalised norms and assumptions. We are hardly indiscriminately all-seeing eyes; we are omnivorous, certainly, but like the Eye of Sauron our voracious absorption of information depends heavily on where exactly our gaze is turned. In this context, what is it that ideology does to enable us to deal with information overload? What tools does it offer us to form a viable representation of the world, to help us choose our hyperreality? * * * One such tool is the iterative process of curating the “recommended-for-you” information that appears as the topmost entries in our search results, home pages, and timelines. The cues we receive are blisteringly “hot”, to use Marshall McLuhan’s term; they are rhetorically and aesthetically marked or tagged—“high-spotted” in Edward Bernays’ phrase—to elicit certain emotional and cognitive reactions, and steer us towards particular “pro–con” attitudes and value-judgments.[2] They “fight for our attention”, clamouring loudly to be the first to be fed through our ideological lenses; and they soon exhaust our capacity (our time, energy, engagement) to scroll ever on and absorb new information. To stave off paralysis, we pick—we have to pick—which bits of information we will inflate, and which we want to downplay. In so doing, we implicitly inflate and downplay the ideological frames and understandings attached to them in “high-spotted” form. Then, of course, the media platform or search engine algorithm remembers and learns our choice, and over time gradually takes the need to make it off our hands, quietly presenting us with only the information (and ideological representations) we “would” (or “should”) have picked out. “Siri, show me what I want to see.” “Alexa, play what I want to hear.” No surprise, then, that the difference in user experience between searching something in our usual browser or a different one can feel like paring away layers of saturation and selective distortion. The fragmentary nature of how we receive information also changes how we express our reaction to it. The ideologically-exaggerated construction of informational cues is designed to provoke instant, “tit-for-tat” responses. At the same time, the promise of “going viral” creates an algorithmic incentive to move first and “move mad” by immediately hitting back in the same medium with a response that is at least as ideologically exaggerated and provocative as the original cue if not more. Gone are the usual cognitive buffers designed to optimise “low-information” reasoning and decision-making. Instead, we are pushed towards the shortest of heuristic shortcuts, the paths of least intellectual resistance, into an upward—and outward (polarising)—spiral of “snap” judgments. The “hot take” becomes the predominant way for us to incorporate the latest information into our ideological pictures of the world; any longer and more detailed engagement with this information is created by literally attaching “takes” to each other in sequence (most obviously via Twitter “threads”). As this practice of instantaneous reaction becomes increasingly prominent and entrenched, our pre-existing mental pictures are steadily overwritten by a worldview wholly constituted as a mosaic of takes: disjointed, simplistic, foundationless, and subjective. As our ideological outlook becomes ever more piecemeal, we turn with growing urgency to the tools and structures of narrative to bring it some semblance of overarching unity. Every day, we consult our curated timelines and the cues it presents to us to discover “the discourse” du jour—the primary topic of interest on which our and others’ collective attention is to focus, and on which we are to have a take. Everything about “the discourse” is thoroughly narrativised: it has protagonists (“the OG Islanders”) and a supporting cast (“new arrivals”, “the Casa Amor girls”), who are slotted neatly into the roles of heroes (Abi, Kaz, Liberty) or villains (Faye, Jake, Lillie); it undergoes plot development (the Islanders’ “journeys”), with story and character arcs (Toby’s exponential emotional growth), twists (the departure of “Jiberty”) and resolutions (the pre-Final affirmations of “Chloby”, “Feddy”, “Kyler”, and “Milliam”). We overcome both the sheer randomness of events as they appear to us, and the pro–con simplicity of our judgments about them, by reimagining each one as a scene in a contemporary (im)morality play—a play, moreover, in which we are partisan participants as much as observers (e.g., by voting contestants off or adding to their online representations). How far this process relies on hermetically self-contained, self-referential certainty becomes clear from the discomfort we feel when objects of “the discourse” break out of this narrative mould. The howls of outrage that the mysterious figure of “H” in Line of Duty turned out not to be a “Big Bad” in the style of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but instead a floating signifier for institutional corruption, shows how conditioned we have become to crave not only decontestation but substantial closure. The final element in our ideological arsenal that helps us cope with the white heat of the cues we receive is our ability to look past them and focus on the contextual and metatextual penumbra that surrounds them. To make sure we are reading our fragmentary information about the world “correctly”, we search for additional clues that take (some or all of) the onus of curating it, coming up with a take about it, and shaping it into a narrative off our hands. This explains, for instance, the phenomenon where audiences experience Love Island episodes on two levels simultaneously, first as viewers and second as readers of the metacommentary in their respective messenger group chats, and on “Love Island Twitter”, “Love Island TikTok”, and “Love Island Instagram”. In extreme cases, we outsource our ideological labour almost entirely to these clues, at the expense of engaging with the information itself, as it were, on its own terms. “Decoding” the messages the information contains then becomes less about knowing the right “code” and more about being sufficiently familiar with who is responsible for “encoding” it, as well as when, where, and how they are doing so. Rosie Holt has aptly parodied this tendency, with her character vacillating between describing a tweet as nice or nasty (“nicety”) and serious (“delete this”) or a joke (“lol”), incapable of making up her mind until she has read what other people have said about it. * * * Together, these elements create a kind of modus vivendi strategy, which we can use to cobble together something approaching a consistent ideological representation of what is going on in the world. But its highly in-the-moment, “choose-your-own-adventure” approach threatens to give us a very emaciated, flattened understanding of what ideology is and does for us. Specifically, it is a dangerously reductionist conception of what ideology has to offer for our inevitable project of choosing a hyperreal mental picture that navigates usefully between (overwhelming, nonsensical) reality and (fanciful, abstruse) drama. If a modus vivendi is all that ideology becomes, we end up condemned to seeing the world solely in terms of competing “mid-range” narratives, without any overarching “metanarratives” to weave them together. These mid-range narratives telescope down the full potential extent of comparisons across space and trajectories over time into the limits of what we can comprehend within the horizons of our immediate neighbourhood and our recent memory. What we see of the world becomes limited to a litany of Game of Thrones-style fragmentary perspectives, more-or-less “(un)reliable” narrations from myriad different people’s angles—which may coincide or contradict each other, but which come no closer to offering a complete or comprehensive account of “what is going on”. The tragic irony is that the apotheosis of this information-management style of ideological modus vivendi is taking place against a backdrop of a reality that is itself taking on ever more dramatic dimensions on an ever-grander scale. Literal catastrophes such as climate change, pandemics, or countries’ political and humanitarian collapse raise the spectral prospect of wholesale societal disintegration, and show glimpses of a world that is simultaneously more fantastical and more raw than what we encounter as reality day-to-day. Individual-level, “bit-by-bit” interpretation is wholly unequipped to handle that degree of overwhelmingness in the reality around us. Curating the information we receive, giving our takes on it, crafting it into moralistic narratives, and interpreting its supporting cues is a viable way to offer an escape (or escapism) from the stochastic confusion of the “petty” reality of our everyday experience—to “leaven the mundanity of your day”, as Bill Bailey puts it in Tinselworm. But it falls woefully short when what we have to face is a reality that operates at a level well beyond our immediate personal experience, which is “sublimely” irreducible to anything as parochial as individual perspective. How unprepared the ideological modus vivendi calibrated to the mediatisation of information today leaves us is shown starkly by the comment of an anonymous Twitter user, who wondered whether we will experience climate change “as a series of short, apocalyptic videos until eventually it’s your phone that’s recording”. If it proves unable to handle such “grand” reality, ideology threatens to become what the Marxist tradition has accused it of being all along: namely, an analgesic to numb us out of the need to take reality on its own ineluctable terms. That, ultimately, is what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were trying to provide through their accounts of historical materialism and scientific socialism: an articulation of a narrative capable of addressing, and as far as possible capturing, the sheer scale and complexity of reality beyond the everyday. We do not have to take all our cues from Marxism—even if, as often as not, “every little helps”. But we do have to inject a healthy dose of grand narrative and metanarrative back into the ideologies we use to represent the world around us, even if only to know where we stand among the tides of social change from which the “newsworthy” events and phenomena we encounter ultimately stem. The trends driving the reality we want to narrate are simultaneously global and local, homogenised and atomised, universal and individuated. We cannot focus on one at the expense of the other. By itself, neither the “Olympian” view of sweeping undifferentiated monological macronarratives (Hegelian Spirit, Whig progress, or Spenglerian decline) nor the “ant’s-eye” view of disconnected micronarratives (of the kind that contemporary mediatisation is encouraging us to focus on) will do. The only ideologies worth their salt will be those that bridge the two. How, then, should ideology respond to the late-modern pressures that are generating “more drama and reality than ever before”? Certainly, it needs to recognise the extent to which these are opposite pulls it has to satisfy simultaneously: no ideological narrative can afford to lose the contact with “gritty” reality that makes it empirically plausible, nor the “production values” of drama that make it affectively compelling. At the same time, it has to acknowledge that the hyperreality it creates and chooses for us is never fully immune to risk. Dramatic “scripting” imposes on reality a meaningfulness and direction that the sheer chaotic randomness of “pure” reality may always eventually belie. Meanwhile, the slavish drive to “accurately” simulate reality may ultimately sap our orientation and motivation in engaging with the world around us of any dramatic momentum. The only way to minimise these risks is to “think big”, and restore to ideology the ambition of “grand” and “meta” perspective, to reflect the maximum scale at which we can interpret both what (plausibly) is and what (potentially) is to be done. [1] Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (Blacksburg, VA: Wilder Publications, Inc., 2010 [1922]), 21–2; John R. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 51. [2] Edward Bernays, Propaganda (Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2005 [1928]), 38; Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (New York, NY: McGraw–Hill, 1964), 22ff. by Iain MacKenzie

Twenty years ago, the lines of debate between different versions of critically-oriented social and political theory were a tangled mess of misunderstandings and obfuscations. The critics of historicist metanarratives were often merged under the banner of postmodernism, grouped together in (sometimes surprising) couplings—postmodernism and poststructuralism, poststructuralism and post-Marxism, deconstruction and postmodernism—or strung together in a lazy list of these terms (and others) that usually ended with the customary ‘etc.’. Although this was partly the result of ‘posties’ still figuring out the detail of their respective challenges to and positions within modern critical thought, it was also a way of finding shelter together in a not altogether welcoming intellectual environment.

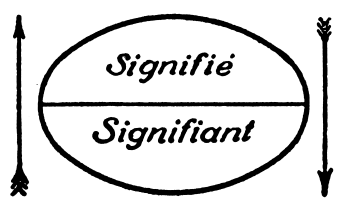

This is because it was not only the proponents of various post-isms who were unsure of what they were defending, it was also that the critics of these post-isms were indiscriminately attacking all the post-isms as one. They would cast their critical responses far and wide seeking to catch all in the nets of performative contradiction, cryptonormativism and quietism. ‘Unravelling the knots’ proposed one way of clarifying one post-ism—poststructuralism—as a small step toward inviting other posties to clarify their own position and critics to take care to avoid bycatch as they trawled the political seas.[1] That was twenty years ago: has anything changed? In many respects, yes; but not always for the better. Within the academy, taking course and module content as a rough indicator, poststructuralism has become domesticated. Once a wild and unruly animal within the house of ideas, it is now a rascally but beloved pet that we all know how to handle.[2] In political studies, this domestication has come in two ways.[3] First, it has become customary to acknowledge one’s embeddedness within regimes of power/knowledge, such that almost everyone of a critical orientation is (apparently) a Foucauldian now. Second, it has become commonplace to study discourses and how they shape identities, adding this to the methodological repertoire of political science. These two simple gestures often merit the titular rubric ‘A Poststructuralist Approach’ and yet they often remain undertheorised in the manner discussed in the original article. Often, there is neither a fully-fledged account of the emergence of structures nor an account of how meaning is constituted through the relations of difference that define linguistic and other structures. Without such in-depth accounts, we are left with empirically rich but ultimately descriptive accounts of how social forces impinge on meaning, which can have its place, or the treatment of language as a data source to be mined in search of attractive word clouds (or equivalents), which can also have its place. Whatever these claims and methods produce, however, it is not helpful to call them ‘poststructuralist’. There is still a need for the exclusive but non-deadening definition of this term, so that it is not confused with the tame house pet with which it is associated today. Part of the problem is that the discussion of how structures of meaning emerge and how they function through processes of differentiation before any dynamics of identification requires, let’s say in a Foucauldian tone, the hard work of genealogy: the patient, gray and meticulous work of the archivist combined with the lively critical work of the engaged activist.[4] But, these days, who has the patience, and the energy, for genealogy? And, in many respects, the difficulties associated with constructing intricate ‘histories of the present’ have led to a tendency to short-circuit the genealogical process (and other poststructuralist methods[5]) under the name of ‘social constructivism’. It is a shorthand, however, that has generated new entanglements, new knots, that have come to define what those of us with a long enough memory can only regret are now frequently labelled the culture wars. On one side, there are the alleged heirs of the posties, awake to the constructed nature of everything and the subtleties of all forms of oppression. On the other side, there are the new defenders of Enlightenment maturity striving to protect science from constructivism and to guard free-speech from the ‘cultural Marxists’. This epithet, of course, is the surest sign that we are in a phoney war—albeit one with real casualties—as it mimics the trawling habits of previous critics but industrialises them on a massive scale. Claims about the deleterious effects of ‘cultural Marxists’ and their social constructivist premisses simply scrape the seabed and leave it barren. But much like the debate twenty years ago, those seeking to defend ‘social constructivism’ cannot swim out of the way unless they specify that this, and other phrases like it, should never be used to end an argument. There is no use in proclaiming a social constructivism if, after all, the social itself is constructed. Shorthand is always helpful but only if we know that it is exactly that and that it will always need careful exposition and explication when critics raise the call. Moreover, what is often forgotten, in the heat of battle, is that the task is not simply to clarify one’s own claims in response to critics but to reflect upon the nature of critical exchange itself. One side of the culture wars take lively spirited debate as the signal of a flourishing marketplace of ideas. Those on the side of social construction appear to agree, simply wanting it to be a regulated marketplace of ideas. What poststructuralism brings to market is succour for neither side. Forms of critical engagement bereft of analyses of the current structures of socially mediated critical practice will always fall short of the poststructuralist project and typically dissolve into the impoverished forms of communicative exchange that never rise above the to-and-fro of opinion. It is incumbent, therefore, on poststructuralists to have a view on the nature of public interaction through social media and how these interlock with different forms of algorithmic governmentality.[6] In this way, the social constructivist shorthand can be given real critical purchase by delving deeply into the nature of public discourse and the technological forms that sustain it, particularly because these make state intervention in the name of ‘the public’ increasingly difficult (even though they can also be used, to a certain extent, for statist purposes). That said, the culture wars obfuscate a deeper misunderstanding about poststructuralism. To grasp this, however, it is important to be reminded of the overarching project of poststructuralism: it is a project aimed at completing the structuralist critique of humanism. It is important to specify this a little further. Humanism can be understood as the project of bringing meaning ‘down to earth’ so that it is in human rather than divine hands. Given this, we can articulate structuralism in a particular way: it was a series of responses to the ways in which humanism tended to treat the human being as a surreptitiously God-like entity and source of all meaning. Structuralism was the project aimed at completing the founding gesture of humanism. Poststructuralism simply recognises that there are tendencies within structuralism that similarly treat structures as analogous to God-like entities that serve as the basis of all meaning. In this respect, poststructuralism is the attempt to complete the project of structuralism, which was itself aimed at completing the project of humanism. When we understand poststructuralism in this manner it is an approach to thinking (and doing) that seeks to remove the last vestiges of enchanted, supernatural, forces, entities and explanations from all theoretical and practical activity, including science but also philosophy and the arts (broadly understood). Given this, there is no room for a pseudo-divine notion of the social that often haunts ‘social constructivism’. Indeed, given this articulation of its project, poststructuralism is hardly anti-science (as some in the culture wars might claim); rather, it is a project of understanding meaning in every respect without reinstating a source of meaning that stands ‘outside’ or ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the world that we inhabit. In fact, poststructuralists (though not all posties) are rather fond of science and they certainly do not want to undermine the natural sciences in the name of lazy ‘social constructivism’. It is, in fact, a way of seeking better science with help of philosophy, and a way of seeking better philosophy with the help of science (and for the full sense of what’s at stake, this gesture should be triangulated through inclusion of the arts). But how can there be a ‘better’ if the posties, including the poststructuralists, are sceptical of metanarratives? This question brings us to one of the more fruitful aspects that has changed in the last twenty years. The most interesting challenge faced by poststructuralists in recent times has come from the emergence of forms of neo-rationalism looking to reinvigorate critical philosophy through pragmatically oriented forms of Kantianism and non-totalising forms of Hegelianism.[7] From the neo-rationalist perspective, poststructuralism has failed in its attempts to naturalise meaning, to take it away from explanations that rely upon supernatural forces, to the extent that it is reliant upon a transcendent notion of Life that treats the priority of becoming over being as given. This immanent critique of poststructuralism cuts much closer to the bone than the Critical Theory inspired fishing which cast their nets wide but always from the harbour of their own shores. At the heart of this dispute is whether or not what we know about the world and how we know what we know about the world can be articulated within a single theoretical framework. For the neo-rationalist, it is (in principle, at least) possible to work on the assumption that there is an underlying unity between ontology and epistemology founded upon a specific conception of reason-giving. For poststructuralists, exploration of the conditions of experience suggests a dynamic distance between the what and the how, such that the task is to secure the claims of philosophy, art and science as equal routes into our understanding of both. While this reconstitutes a certain return to the pre-critical debates between rationalists and empiricists, it is equally indebted to the critical turn with respect to the shared task of legitimating knowledge claims, but with a pragmatic or practical twist. Both the neo-rationalists and the poststructuralists pragmatically assess the worth of the knowledge produced by virtue of the challenges they proffer to arguments that rely upon a transcendent God-like entity and the dominant form of this today; namely, the sense of self-identity that underpins capitalist endeavours to maximise profit. This critical perspective, perhaps surprisingly, was seeded within the fertile soil of American pragmatism. For the pragmatists—and we might think especially of Pierce, Sellars, and Dewey—it is the practical application of philosophy that engenders standards of truth, rightness and value. Admittedly, in the hands of its founding fathers, this practical application was often guided by the idea of maintaining the status quo. But that is not essential. Neo-rationalists and poststructuralists have found a shared concern with the idea that philosophical practice should be guided by the critique of capitalist forms of thought and life. As such, they share a common ground upon which meaningful discussion can be forged, aside from the culture wars (which are simply a reflex of capitalist identitarian thinking). While deep-seated divisions remain—does the knowledge generated by social practices of reason giving trump the experience of creative learning or are they on the same cognitive footing?—the shared sense of seeking a critical but non-final standard for what counts as better (better than the identity-oriented thinking sustaining capitalism) is driving much of the most productive debate and discussion at the present time. Work of this kind reminds us that poststructuralism is still a wild animal rather than a domesticated house pet, that it is a critical project but also one that has political intent. That said, it is not always easy to convey the political dimension of poststructuralism, especially given the vexed question of its relationship to ideology. As discussed in the original article, part of the initial excitement about poststructuralism was that its major figures distanced themselves from the idea of ideology critique. However, this was only ever the beginning of a complex story about the relationship of poststructuralism to ideology and never the end.[8] While Marxist notions of ideology were critiqued for the ways in which they incorporated notions of the transcendental subject, naïve versions of what counts as real and over-inflated notions of truth, poststructuralists have always endorsed the power of individual subjects to express complex notions of reality and historically sensitive and effective notions of truth, and to do so against dominant social and political formations. These formations are often given unusual names—dispositif, assemblages, discourses, and such like—but the aim of unsettling and ultimately unseating the dogmatic images and frozen practices of social and political life is not too distant from that animating Marxism. Of course, as Deleuze and Guattari expressed it, any revised Marxism needs to be informed by significant doses of Nietzscheanism and Freudianism (just as these need large doses of Marxism if they are to avoid becoming critically quietest and practically relevant for the critique of capitalism).[9] What results, though, is an immanent version of ideology critique rather than a rejection of it tout court: there are many assemblages/ideologies that dominate our thoughts, feelings and behaviour and it is possible to learn how they operate by making a difference to how they function and reproduce themselves. In searching for the natural bases of meaningful worlds it is no surprise that poststructuralists have become adept at diagnoses of how natural processes can lead to systems of meaning that import supernatural fetishes into our everyday lives, and how these are sustained in ways even beyond merely serving the interests of the economically powerful. There appear to be an endless number of these knots that need untying. If we want to untie at least some of them, then unravelling the knots that currently have poststructuralism tangled up in a phoney culture war is another small step on the road to bringing a meaningful life fully down to earth. [1] I.MacKenzie, ‘Unravelling the knots: post-structuralism and other “post-isms”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 6 (3), 2001, pp. 331–45. [2] I. MacKenzie and R. Porter, ‘Drama out of a crisis? Poststructuralism and the Politics of Everyday Life’, Political Studies Review, 15 (4), 2017, pp. 528–38. [3] One of the interesting features of the recent history of poststructuralism is that it is not the same across disciplines. Of course, this need for disciplinary specificity with respect to how knowledge is disrupted, new forms of knowledge established and then domesticated is part of what poststructuralism offers. That said, much of what follows can be read across various disciplines in the arts, humanities, sciences and social sciences to the extent that the legacies of humanism and historicism traverse these disciplines. [4] M. Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in D. Bouchard (ed.) Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault (New York: Cornell University Press, 1992 [1971]), pp. 139–64. [5] B. Dillet, I. MacKenzie and R. Porter (eds) The Edinburgh Companion to Poststructuralism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013). [6] A. Rouvroy, ‘The End(s) of Critique: data-behaviourism vs due-process’ in M. Hildebrandt and E. De Vries (eds), Privacy, Due Process and the Computational Turn. Philosophers of Law Meet Philosophers of Technology (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 143–68. [7] See R. Brassier’s engagment with the work of Wilfrid Sellars, for example: 'Nominalism, Naturalism, and Materialism: Sellars' Critical Ontology' in B. Bashour and H. Muller (eds) Contemporary Philosophical Naturalism and its Implications (Routledge: London, 2013). [8] R. Porter, Ideology: Contemporary Social, Political and Cultural Theory (Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2006) and S. Malešević and I. MacKenzie (eds), Ideology After Poststructuralism (Oxford: Pluto Press, 2002). [9] G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (New York: Viking Press, 1977). This triangulation of the philosophers of suspicion, with a view to completing the Kantian project of critique, is one especially insightful way of reading this provocative text: see E. Holland, Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis (London: Routledge, 2002). by David Benbow

The concept of ideology seems to have been supplanted in contemporary critical theory by the concept of discourse.[1] Postmodernist scholars, such as Michel Foucault[2] and Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari,[3] have criticised the concept of ideology. Nonetheless, the two concepts are potentially compatible.[4] I believe that the concept of ideology is superior to the concept of discourse because, as David Hawkes noted, it mediates between the ideal and the material.[5] The work of the Frankfurt School philosopher, Theodor Adorno, and his conceptualisations of ideology, are particularly useful in examining the relationship between the ideal and the material in modern neoliberal societies.[6] The contemporary relevance of Adorno’s work is evident in the burgeoning literature concerning the philosopher—see, for example, Blackwell’s A Companion to Adorno, published in 2020, which contains the largest collection of essays by Adorno scholars in a single volume.[7] I have utilised Adorno’s conceptualisations of ideology, within my own work, to examine different aspects of the law relating to health and healthcare.

Adorno’s distinction between liberal ideology and positivist ideology,[8] and his conceptualisations of reification, informed my analysis of reforms which have marketised and privatised the English National Health Service (NHS).[9] I also made use of Adorno’s method of ideology critique to demonstrate how many public statements regarding the high-profile Charlie Gard[10] and Alfie Evans[11] cases (which involved disputes between parents and clinicians regarding the treatment of young infants), for example by United States (US) politicians (such as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz), were unjustifiably critical of socialised medicine.[12] The cases led to renewed proposals for the best interests test,[13] which is currently determinative in such cases, to be replaced with a significant harm test. I employed Adorno’s notion of the dialectic of enlightenment (the idea that reason can engender unreason[14]) to undermine the argument that parents would make better decisions in these types of cases.[15] I contended that the clinicians in such cases reflexively acknowledged the limits of medicine, in contrast to the parents, who appear to have suffered from false hope.[16] Adorno’s ideas are also informing my current research projects on vaccine confidence (and the influence of anti-vaccination ideology) and the potential of human rights to address health injustices in states within the Global South. In respect of the former, I have employed the psycho-social dialectic methodology that Adorno developed in his research into anti-Semitism[17] to identify the objective social factors which have influenced the increase in vaccine hesitancy.[18] In respect of the latter, Adorno noted that rights may be tacitly critical of existing conditions[19] and thus I am developing a paper regarding how they may be used to articulate present injustices within the Global South (and elsewhere) with a view to their remedy. In the chapter on the topic of the concept of ideology, published as part of the Frankfurt School’s book Aspects of Sociology, Adorno distinguished between liberal ideology and positivist ideology.[20] In Adorno’s view, positivist ideology, which he thought was becoming more prominent in modern societies, hardly says more than ‘things are the way they are’.[21] By contrast, the emphatic concepts of liberal ideology, such as freedom, equality and rights, are often used, within discourse, to justify certain states of affairs (or changes to them).[22] Such emphatic concepts can also be used to critique existing conditions. There are different modalities of the related concept of reification in Adorno’s work. One modality of reification in Adorno’s work is philosophical reification, which refers to phenomena being treated as fixed.[23] An example of philosophical reification is the exchange principle, which treats unlike things alike.[24] Another modality of reification in Adorno’s work is social reification, which refers to means becoming ends in themselves.[25] Both of these modes are evident in consumerism. Reification may lead to estrangement, whereby people become strangers or enemies to one another.[26] Estrangement is the opposite of solidarity, which Rahel Jaeggi defines as ‘standing up for each other because one recognises one’s own fate in the fate of the other’.[27] Reification may undermine the solidarity which has been pivotal in the creation and continuation of the NHS. I have analysed the emphatic concepts of freedom and equality and how they have been used within the discourse of successive governments regarding the English NHS. I have also considered the potential reifying effects of the market reforms that successive governments have implemented within the English NHS. When the NHS was established, in 1948, it was to be publicly answerable via ministerial accountability to Parliament. However, this was deemed to be a constitutional fiction.[28] Since the 1970s, there have been efforts to enhance patient and public involvement within the NHS via two types of mechanisms, identified by Albert Hirschman: voice and choice.[29] In the neoliberal era, the preference has been for choice mechanisms (although attenuated voice mechanisms have persisted). This preference is evident in the use of indicators and market mechanisms to facilitate competition among NHS providers. The internal market introduced by the Conservatives, in the 1990s,[30] was justified on the basis of enhancing patient choice,[31] although evidence indicates that it reduced the choices available to patients.[32] The mimic-market established in the English NHS by the New Labour governments, in the 2000s, afforded private healthcare companies increasing opportunities to deliver NHS services and gradually extended patient choice to any willing provider.[33] New Labour sought to naturalise the relationship between patients and the NHS as a consumerist one.[34] However, studies indicate that many patients were recalcitrant in this regard[35] and often did not utilise the opportunity to exercise choice when it was available to them.[36] The latest English NHS market was introduced by the Health and Social Care (HSC) Act 2012. This statute places duties on commissioners to act with a view to enabling patients to make choices.[37] Such commissioners are also required to comply with regulations passed pursuant to S.75 of the statute,[38] and, prior to Brexit, with European Union (EU) public procurement law,[39] in tendering services. Such laws have coaxed many commissioners into tendering services in circumstances where they did not think that it was best for patients, [40] which is symptomatic of social reification, as the market has become an end in itself. New methods for enabling patients to compare providers, such as friend and family test (FFT) scores, have also been introduced. These are symptomatic of philosophical reification, as the process of reducing quality (patient experiences) into quantity (a number) is one of abstraction,[41] which is unlikely to capture the complexity of patient experiences. In any event, patient choice, which was used to justify the coalition’s reforms, has taken a backseat,[42] and the market created by the HSC Act 2012 has primarily involved providers competing for tenders. The intention of many of the policymakers who designed the market reforms to the English NHS thus seems to have been to get private providers into the NHS, rather than to extend patient choice. I contend that voice mechanisms are a preferable method of empowering patients by allowing them to convey the complexity of their experiences and to influence clinical practices. Adorno was critical of the concept of equality, on the basis that it could obscure important differences.[43] Nonetheless, equality of access to the NHS (based on need) and the reduction of health inequalities are principles which, I contend, are compatible with an Adornian perspective. The Welsh Marxist theorist, Raymond Williams, helpfully distinguished between dominant, residual, and emergent norms within his work. [44] I have conceptualised neoliberal norms (such as competition and choice) as dominant norms, the founding principles of the NHS (such as equality of access, comprehensiveness, and universality) as residual norms (as they are remnants from the era of the social democratic consensus, which preceded the neoliberal era) and the reduction of health inequalities as an emergent norm.[45] In the neoliberal era, different UK governments have all articulated their support for the residual norm of equality of access. However, this has been undermined, for example, by the ability of foundation trusts to earn 49% of their income from private patients.[46] The other residual norms, such as comprehensiveness, have also been undermined by successive governments, within the neoliberal era, thereby extending the exchange principle (as patients are now required to pay for some health services). The issue of health inequalities was not a priority of the Conservative governments between 1979 and 1997, which sought to bury the Black Report[47] and which rebranded such inequalities, in a positivistic manner, as health variations.[48] In contrast, both the New Labour governments between 1997 and 2010 and the Conservative-led governments since 2010 have adopted the goal of reducing health inequalities. The HSC Act 2012 created statutory duties for different actors to have regard to the need to reduce such inequalities.[49] However, the impact of the main economic policy (austerity) pursued by governments since 2010, has increased such inequalities.[50] Austerity negatively affected NHS capacity and resources, as well as population health, rendering the NHS less resilient to the current Covid-19 pandemic.[51] The reduction of health inequalities requires alternative economic policies to austerity. Ultimately, I have identified both liberal and positivistic elements in the discourse of successive governments, in the neoliberal era, in relation to the English NHS. Consequently, government discourse pertaining to the English NHS has not become completely positivistic. Rather, there are liberal elements which provide members of the public and scholars with a basis for critique. The statements of successive governments that they were desirous of empowering patients, respecting the NHS’ founding principles and reducing health inequalities can be used to critique their policies (which have not empowered patients, have undermined the NHS’ founding principles and are likely to exacerbate health inequalities) and to conceive alternative policies. The development of sustainability and transformation plans (STPs), integrated care systems (ICSs) and integrated care providers (ICPs), and the increased emphasis on integration in the discourse of the government and NHS England (a non-departmental body which oversees the day-to-day operation of the NHS in England and commissions primary care and specialist services) has been interpreted by many as a move away from the competition that has dominated the English NHS in the neoliberal era.[52] A recent Kings Fund report found that there has been a move away from procurement to collaboration within the English NHS (with the former being used as a method of last resort).[53] However, some fear that the new structures being established within the English NHS may undermine its founding principles and afford new opportunities for private companies.[54] I have argued elsewhere that the policies of successive governments pertaining to the English NHS were indicative of market fetishism.[55] The recent award of many contracts to private companies under special powers that circumvent normal tendering rules, during the Covid-19 pandemic,[56] suggests a fetishism for private companies and not necessarily with competitive processes. I have identified the corporate influence on the reforms to the English NHS of successive governments.[57] Such corporate influence has ostensibly also affected the current government’s response to the pandemic.[58] Although I have identified several potential reifying effects of government reforms to the NHS, which could undermine the solidarity which led to its creation and continuation, the adherence of the public to unprecedented rules, such as national lockdowns, during the Covid-19 pandemic, to ‘Protect the NHS’ (as government slogans state), is a palpable contemporary manifestation of such solidarity. The pandemic has also exposed the impact of persistent health inequalities.[59] If efforts to undermine the founding principles of the NHS continue, the slogan ‘Protect the NHS’ will persist as a powerful means of providing an immanent critique of government policies. Additionally, growing awareness of health inequalities may lead to increased clamour for more action than government promises and statutory duties. [1] Rahel Jaeggi, ‘Rethinking Ideology’, in Boudewijn de Bruin and Christopher F. Zurn (eds.), New Waves in Political Philosophy (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 63. [2] Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1980), 118. [3] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Continuum, 1987), 76. [4] Trevor Purvis and Alan Hunt, ‘Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology...’, The British Journal of Sociology, 44(3) (1993), 498. [5] David Hawkes, Ideology: 2nd Edition (London: Routledge, 2003), 156. [6] See, for example, Charles A. Prusik, Adorno and Neoliberalism: The Critique of Exchange Society (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020); Deborah Cook, Adorno, Foucault and the Critique of the West (London: Verso, 2018). [7] Peter E. Gordon, Espen Hammer, and Max Pensky (eds.), A Companion to Adorno (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2020). [8] See Theodor Adorno, ‘Ideology’, in Frankfurt Institute of Social Research (ed.), Aspects of Sociology, (London: Heinemann, 1973), 202. [9] David Benbow, ‘An Adornian Ideology Critique of Neo-liberal Reforms to the English NHS’, Journal of Political Ideologies 26(1) (2021), 59–80. [10] Great Ormond Street Hospital v Constance Yates, Chris Gard and Charles Gard (A Child by his Guardian Ad Litem) [2017] EWHC 972 (Fam) [20]. [11] Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust v Mr Thomas Evans, Ms Kate James, Alfie Evans (A Child by his Guardian CAFCASS Legal) [2018] EWHC 308 (Fam) [6]. [12] David Benbow, ‘An Analysis of Charlie’s Law and Alfie’s Law’, Medical Law Review 28(2) (2020), 227. [13] Children Act 1989, S.1(1). [14] See Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), xvi. [15] Benbow, ‘An Analysis’, 237–8. [16] Ibid. [17] Theodor Adorno, The Psychological Technique of Martin Luther Thomas' Radio Addresses (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010). [18] The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared this to be a global health threat in 2019. See WHO, ‘Ten threats to global health in 2019’, available at https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed 29 October 2020). [19] Adorno and Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 141. [20] Adorno, ‘Ideology’, 202. [21] Ibid. [22] Deborah Cook, ‘Adorno, Ideology and Ideology Critique’, Philosophy & Social Criticism 27(1) (2001), 10. [23] Anita Chari, A Political Economy of the Senses: Neoliberalism, Reification, Critique (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2015), 144. [24] David Held, Introduction to Critical Theory: Horkheimer to Habermas (Cambridge: Polity, 2004), 220. [25] Chari, Political Economy of the Senses, 144. [26] John Torrance, Estrangement, Alienation and Exploitation: A Sociological Approach to Historical Materialism (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1977), 315. [27] Rahel Jaeggi, ‘Solidarity and Indifference’, in Ruud ter Meulen et al (eds.), Solidarity and Health Care in Europe (London: Kluwer, 2001), 291. [28] Alec Merrison, Report of the Royal Commission on the National Health Service, Cmnd 7615. (London: HMSO, 1979), 298. [29] Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organisations and States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970). [30] Via the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990. [31] Department of Health, Working for Patients (London: Stationery Office, 1989), 3–6. [32] Marianna Fotaki, ‘The Impact of Market-Oriented Reforms on Choice and Information: A Case Study of Cataract Surgery in Outer London and Stockholm’, Social Science & Medicine 48(100 (1999), 1430. [33] Department of Health (DOH), Principles and Rules for Co-operation and Competition (London: DOH, 2007), 10. [34] For example, the word consumer appeared more in Labour’s health policy documents than in its policy documents for other policy areas. See Catherine Needham, The Reform of Public Services under New Labour: Narratives of Consumerism (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), 115. [35] John Clarke, Janet Newman, and Louise Westmarland, ‘Creating Citizen-Consumers? Public Service Reform and (Un)willing Selves’ in Sabine Maasen and Barbara Sutter (eds.), On Willing Selves: Neoliberal Politics vis-à-vis the Neuroscientific Challenge (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), 136. [36] Anna Dixon, Patient Choice: How Patient’s Choose and How Providers Respond (London: Kings Fund, 2010), 20. [37] NHS Act (2006), S.13I and S.14V as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25. [38] National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations (No.2) (S.75 Regulations), SI 2013/500. [39] Directive 2014(24) EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on Public Procurement and repealing directive 2004/18/EC, OJ L. 94, 28 March 2014. This was implemented in the UK via the Public Contracts Regulations, SI 2015/102. Such regulations are still in force. [40] D. West, ‘CCGs open services to competition out of fear of rules’, Health Services Journal, 4 April 2014. [41] Theodor Adorno, Lectures on Negative Dialectics: Fragments of a Lecture Course 1965–1966 (Cambridge: Polity, 2008), 127. [42] Chris Ham et al., The NHS under the Coalition government part one: NHS Reform (London: Kings Fund, 2015), 18. [43] Theodor Adorno, Negative Dialectics (New York: Continuum, 1973), 309. [44] Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 122. [45] David Benbow, ‘The sociology of health and the NHS’, The Sociological Review 65(2) (2017), 416. [46] NHS Act (2006), S.43(2A) as amended by Health and Social Care (HSC) Act (2012), S.164(1). [47] Department of Health and Social Service (DHSS), Inequalities in Health: Report of a Research Working Group (London: DHSS, 1980). [48] Clare Bambra, Health Divides (Bristol: Policy Press, 2016), 185. [49] For example, the Secretary of State for Health is required to have regard to the need to reduce health inequalities in exercising their functions (NHS Act (2006), S.1C as amended by the HSC Act (2012), S.4.) and NHS England and CCGs are required to have regard to the need to reduce inequalities in respect of access (NHS Act (2006), S.13G(A) and S.14T(A) as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25) and outcomes (NHS Act (2006), S.13G(B) and S.14T(B) as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25). [50] Clare Bambra, ‘Conclusion: Health in Hard Times’ in Clare Bambra (ed.), Health in Hard Times: Austerity and Health Inequalities (Bristol: Policy Press, 2019), 244. [51] Chris Thomas, Resilient Health and Care: Learning the Lessons of Covid-19 in the English NHS (London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2020), 3. [52] Hugh Alderwick et al., Sustainability and Transformation Plans in the NHS: How are they being developed in practice? (London: Kings Fund, 2016), 7. [53] Ruth Robertson and Leo Ewbank, Thinking Differently about Commissioning (London: Kings Fund, 2020). [54] Allyson M. Pollock and Peter Roderick, ‘Why we should be concerned about Accountable Care Organisations in England’s NHS’. British Medical Journal 360 (2018). [55] Benbow, ‘The sociology of health and the NHS’, 420. [56] British Medical Association (BMA), The role of private outsourcing in the Covid-19 response (London: BMA, 2020), 4. [57] Benbow, ‘An Adornian Ideology Critique’, 66, 68. [58] Peter Geoghegan, ‘Cronyism and Clientelism’, London Review of Books 42 (2020). [59] Abi Rimmer, ‘Covid-19: Tackling health inequalities is more urgent than ever, says new alliance’. British Medical Journal 371 (2020). 11/1/2021 The quarter-century renaissance of ideology studies: An interview with Michael FreedenRead Now by Marius S. Ostrowski

Marius Ostrowski: Perhaps to start with a retrospective view, and a simple question. What first prompted the idea to found the Journal of Political Ideologies?