|

17/4/2023 (Re)inventing the nation on the centenary of the Turkish Republic: A Rhetorical Political Analysis of Erdogan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’Read Now by Arife Köse

History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogeneous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now [Jetztzeit].

- Walter Benjamin - On 28 October 1923, dining with his friends, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is said to have declared ‘Gentlemen! We are going to announce the Republic tomorrow.’ The next day, he proclaimed the following law: ‘The form of government of the Turkish state is the republic.’[1] Once the law passed by the Turkish Parliament later the same day, the State of Türkiye as republic, which is now a century old, came into being. From one perspective, that date—29 October 1923—is just a place on the calendar, ‘chronos’, or quantitative time. However, as Benjamin argued, calendars are also ‘monuments of historical consciousness,’[2] marking out moments of what rhetoricians call ‘kairos’—measuring not quantity of time but a quality of timely action. Kairos points to the ‘interpretation of historical events’ because it is about the significance and meaning assigned to them.[3] It is also about the opportunity to be grasped now for action that cannot be grasped under different conditions or situations. Thus, kairos always has an argumentative character since the significance given to historical events are always contested and temporarily decontested in specific ways. In this respect, due to the significance and meaning assigned to it, the foundation of the Turkish Republic can be understood as a moment when ‘chronos is turned into kairos’.[4] Now, 100 years since its foundation, the country’s incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is seeking to create a moment of kairos again, using it to reinvent the idea of ‘Turkishness’ itself and to turn it into a time of action in the service of continuity of his rule. This is a rhetorical act that requires ideological analysis. In this article, I examine how Erdoğan fulfils such a rhetorical act through Rhetorical Political Analysis (RPA) of the speech he delivered on 28 October 2022. This speech was intended to set forth his vision for the future of the country on the day that the Turkish Republic entered its centenary and was entitled a ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. I will begin by providing some historical and theoretical background, followed by a rhetorical analysis of his political thinking around the centenary. My argument is not only that his ideological thinking shapes his actions but also his understanding of Turkishness in the context of the centenary is shaped by his strategic action, aiming at winning the elections in Türkiye in 2023 and consolidating his and his party’s leadership position in the future. Background As 29 October 2023 marks the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Erdoğan, as both President of Türkiye and leader of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), delivered a speech on 28 October 2022 to set out the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. The gathering was held in the capital Ankara, in Ankara Sports Hall which accommodates 4,500 people. 11 political parties were invited to the event. The only party that was not invited was the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), the Kurdish-led, left-wing party which has been denounced by Erdoğan as a ‘terrorist’ entity due to its alleged connection with PKK, the Kurdish paramilitary organisation. Alongside the political parties, AKP Members of Parliament, mayors, party members, and supporters were invited to the event—as well as some artists, NGOs, academics, and journalists (unusually including notable dissident journalists). The event, at which Erdoğan spoke for 1 hour 40 minutes, lasted 2 hours overall.[5] Like the morphological approach to ideological analysis pioneered by Michael Freeden,[6] rhetorical approaches to ideologies start from the position that political ideologies are ubiquitous, and a necessary part of political life. However, unlike morphological analysis, they focus on ideological arguments rather than ideological concepts, on the grounds that ideologies are ‘shaped by and respond to external events and externally generated contestation from alternative ideologies’.[7] Accordingly, Alan Finlayson suggests using RPA to analyse ideologies, in order to pay attention not only to the semantic and structural configuration of ideologies but also to political action, such as the strategies that political actors develop to intervene in specific situations. Further, RPA focuses on the performative aspect of political ideologies by drawing attention to how performativity becomes part of the morphology of the ideology in-question through foregrounding specific political concepts.[8] Alongside the concepts provided by the rhetorical tradition, RPA also draws on kinds of proof classically categorised as ethos, pathos and logos.[9] Whereas ethos indicates appeal to the character of the speaker with whom the audience is invited to identify, pathos is about appeal to the emotions. Lastly, logos indicates appeal to reason by political actors in their attempt to have the audience reach particular conclusions by following certain implicit or explicit premises in their discourse. Overall, RPA commits to the analysis of politics ‘as it appears in the wild’.[10] The rhetorical situation Analysis of political speeches begins with the analysis of the rhetorical situation, since every political speech is created and situated in a particular context. In this respect, every political speech, alongside its verbal manifestation, performs an act by intervening in a particular situation.[11] Those situations are characterised by both possibilities and restrictions for the orator, and it is one of the primary characteristics of skilled orators to know how to employ the opportunities and overcome the restrictions embedded in the situation. In such situations, political ideologies are not only deployed by political actors to intervene in and shape the situation, but they are also shaped through the act of intervention when addressing the challenges or trying to persuade others of a particular action. In the case of Erdoğan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ there are two exigencies: first, for him, it is a moment of kairos to be grasped and put in the service of his strategic aim of winning the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023. For this, evidently, he needs to prove to the people beyond his supporters that he is the leader of the whole country who can carry it into the future. Thus, it is an opportunity for him to amplify his rule as President of Türkiye, which is a position that he gained as a result of regime change in Türkiye 2017. On 16th April 2017, Turkish voters approved by a narrow margin constitutional amendments which would transform the country into a presidential system. This was followed by the re-election of Erdoğan as the President of the country on 24 June 2018 with the support of MHP (Nationalist Movement Party). Since then, AKP and MHP work together under the alliance called People’s Alliance. The new system has been widely criticised on the grounds that it weakens the parliament and other institutions and undermines the separation of powers through politicisation of the judiciary and concentration of executive power in a single person. Overall, this has led to an increasingly authoritarian governance.[12] The second exigency for Erdoğan is the enduring economic crisis from which the country has been suffering since June 2018. In that year, as a result of Erdoğan’s insistence on lowering interest rates, Türkiye experienced an economic shock, resulting in a dramatic loss in the value of Turkish Lira against Dollar. Since then, three Turkish Central Bank governors have been successively dismissed by Erdoğan. For example, in March 2021, Erdoğan fired then governor Naci Ağbal after he hiked the interest rates against Erdoğan’s persistence on not increasing them no matter what. Erdoğan replaced him with Şahap Kavcıoğlu, known for his loyalty to Erdoğan. Such a move made the economic situation in Türkiye even worse. One of the economic commentators in the Financial Times wrote, ‘Erdoğan’s move leaves little doubt that all the power in Türkiye rests with him, and this will result in rate cuts. This will simply make Türkiye’s inflation problem even worse.’[13] The overall consequence of this turmoil has been rising prices as the Lira collapsed and wages remained stagnant, causing a dramatic drop in people’s purchasing power. By August 2022, according to research, 69.3 percent of the Turkish population were struggling to pay for food.[14] In November 2022, after Erdoğan delivered the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’, the inflation rate reached 85.5%.[15] Erdoğan had to address these two exigencies while he was under heavy criticism not only from international actors and his national opponents but also from the rank and file of his own party about Türkiye’s economy and democracy. His leadership has also been weakening for some time. Erdoğan’s loss in the two big municipalities—Ankara and Istanbul—in the local elections in 2019 exposed the myth that he is a leader who never loses an election. This was the context in which the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ event was held. It was a kairological moment for Erdoğan, where he attempted to reinvent Turkishness and decontest its meaning through an ideological speech-act manifested through various rhetorical moves to position him and his party as the only option in the upcoming elections. The arrangement of the speech Political speeches are significant for the analysis of ideologies not only because of what political leaders say but also because they provide us with the opportunity to observe how the political leader in-question, the nation, and the audience are positioned both in the speech and on the stage. Therefore, paying attention to the arrangement of the speech is as important as the text of the speech. ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ begins with a performance including video clips with narrations, dance performances, songs, and poems. The decoration of the hall can also be thought of as part of this performance. This part of the event can be considered as what is called the ‘prologue’ of the speech in the rhetorical tradition and is also part of ideological analysis. The second part of the event consists of Erdoğan’s speech, where he begins by saluting people in the hall and then praising the Republic and those who fought in the War of Salvation for five minutes. He talks for 35 minutes about the significance of the AKP in the context of the centenary by explaining what it has achieved so far. Following this, he drones on about his party’s achievements by marshalling the services provided by the AKP under his leadership, which lasts for about 20 minutes. After that, he talks about his promises for the ‘Century for Türkiye’ for 20 minutes. In the closing section of the speech, he asks everyone in the hall to stand up and take a nationalist oath with him by repeating his words: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be great! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ In sum, the whole speech consists of two main parts of which the first is about glorifying the Turkish nation and the second part is primarily concerned with the AKP and Erdoğan himself. The speech is therefore arranged in a way which conflates the nation with AKP and Erdoğan and argues for an indispensable bond between them. History without contingency The event begins with a narration by a male presenter accompanied by sentimental music, speaking about the ‘limitless’ and ‘mystical’ universe that operates with self-evident ‘balance’ and ‘order’. We are told that all we do is ‘to find our place within this universe’, and ‘whatever we do, do it right’. Then, around 25 people representing different age groups, genders, and occupations stage a dance performance, embodying the Turkish nation: comprised of a variety of people yet performing the same movements harmoniously under the same flag. In this part, first and foremost, the Turkish nation is situated in its place in time and history. We only hear a narration without seeing the actual person speaking and this narration is accompanied by a video show. The voice asks us to commence history with ‘the moment that the horizon was first looked at’; with the moment that ‘the humanity became humanity’. Within this transcendental history whose origin is undeterminable, the beginning of the Turkish nation is also rendered ambiguous. We are told: If you are asked when this journey began, your response should be ready: When the love of the homeland began! Thus, the origin of Turkish nation is situated into a self-evident kairos without chronos as if its existence is free from the contingent flow of events throughout history. This arrest of contingency is further amplified through the topos of a ‘nation who always does the right thing’: You had forty paths, and maybe forty horses too. If you had not chosen the right thing, you would not have been able to arrive at your homeland, today, now. You chose the right thing even if it was the hard one. Moreover, according to the narration, Turkish nation is a nation which acts now through considering the future; thus, its now is always oriented to the future: You have always envisaged tomorrow. Your history has been written with your choices. Hence, the future also means you. Here we see a nation that always knows what it is doing, always does the right thing and has the power to shape history through the choices it makes. Its actions are always determined by its vision for the future and its future is not contingent but is destiny; a ‘journey’ with its own telos. Then, the narrator asks, ‘when does the future begin?’ and adds, ‘this is the biggest question. The most important question is where the future begins.’ But, this time, we are not left in ambiguity. We are told that it begins ‘here,’ ‘today,’ ‘now’. Strikingly, today is only meaningful as a point of beginning of the future. Hence, our present is also arrested by both our past and our future. We do not have the right to choose our own kairos—our right time for action for a future that is designated by us—but are destined to conform to the already designated kairos for us within, again, already designated chronos: our possibility to have alternative ‘now’ and alternative ‘future’ is taken from us. The ethos of Turkishness Such an articulation of transcendental Turkishness with time and history is amplified with the further delineation of the ethos of the nation. Accordingly, for Erdoğan, the Turkish nation consists of ‘siblings’ who are united under and through the same ‘crescent’—the crescent on the Turkish flag. This is a nation who has the courage and strength to challenge the entire world. Connoting the lyrics of Turkish National Anthem, the lyrics of one of the songs that performed in the event reads: Who shall put me in chains Who shall put me in my place. Then the song continues by saying: There is no difference between us under the crescent We are not scared of coal-black night We are not scared of villains Nevertheless, nowhere in the speech are we told who those ‘villains’, or people who want to ‘put us in chains’ are. Although they cannot stop us from our way, we are expected to consider their existence when we act. Here, we see the manifestation of the ethos of Turkishness through its association with the concepts of freedom, understood as sovereignty, and the Turkish flag. Türkiye is presented as a nation where differences between its members perish under the uniting power of the Turkish flag, and when acting, it always prioritises the protection of its sovereignty. Furthermore, it is argued, the most definitive characteristic of the Turkish nation is that it never stops; it is always in motion, walking towards the future. Thus, the current Turkish Republic constitutes just a small part of its ‘thousand years of life’ so far. However, the Republic is important because it proves what the Turkish nation is capable of: it can achieve the unachievable, and it can overcome the toughest obstacles. But Turkish nation’s ambitions cannot be limited to the current Republic, and no matter how much it suffers now it must keep moving towards the future. In his speech, Erdoğan also uses the metaphor of a bridge, which can be thought together with this topos of ‘nation in motion’. He says, ‘We will raise the Turkish Century by strengthening the bridge we have built from the past to the future with humanistic and moral pillars’. Here, the ‘bridge’ signifies the uninterrupted continuity between past and future built by Erdoğan and his party, where the present is only characterised as a transition point in the ‘journey’ of the Turkish nation towards the future. The performative construction of Turkishness is also accompanied by its articulation with its state, flag and homeland which are the core concepts of Erdoğan’s nationalism that he summaries with the motto ‘one nation, one flag, one state, one homeland.’ For example, in the middle of the hall, there is a huge sundial hanging from the roof, and there is a huge star and crescent on the floor under it that represent the Turkish flag and the homeland. Furthermore, there are 16 balls hanging around the sundial, representing the 16 states founded by Turks throughout history. In Erdoğan’s political thinking, ‘one nation’ signifies indivisible community where the nation is characterised by its ethnic and religious origins- namely being a Turkish and Sunni Muslim. ‘One flag’, on the other hand, signifies the Turkish flag, consisting of red representing the blood of martyrs killed in the Turkish War of Independence, and the white crescent and the star representing the independence and the sovereignty of the country. While ‘one homeland’ represents the land of Türkiye, ‘one state’ signifies the powerful and united Turkish state. The role of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) So far, we have been told who we are, where we are coming from and where we are going, and now, the stage is Erdoğan’s. Erdoğan’s speech consists of three points: situating his party and himself within the history of the Republic by explaining what they have done so far, emphasising his role in this process, then, explaining his promises for the next ‘Century for Türkiye’. For Erdoğan, the AKP is the guarantee of continuity between the past and the future. Accordingly, after beginning his speech by praising Atatürk and the people who fought in the War of Independence, he continues by saying: Of course, there were good things initiated in the first 80 years of our Republic, some of which have been brought to a conclusion. However, the gap between the level of democracy and development that our country should have attained and where we were was so great. Then AKP came into power, his story goes on, and ‘made Türkiye bigger, stronger and richer’ despite all the ‘coup attempts’ and ‘traps’. It was the AKP who actualised ‘the most critical democratic and developmental leap with common sense, common will and common consciousness going beyond all types of political or social classifications’ by including everyone who has been oppressed and discriminated in Türkiye, from Kurds to Jews. Hence, we are told, it is the AKP who will build the Century for Türkiye through the ‘bridge that it establishes from the past to the future’. The ethos of Erdoğan Erdoğan also positions himself as the leader who has brought Türkiye up to date and, thus, the person who can take it into the future. Erdoğan claims that today he is there as a ‘brother’, ‘politician’, and ‘administrator’, as someone who has devoted all his life to the service of his country and the nation. He emphasises that he is there with the confidence that stems from his ‘experience’ in running the country. He then situates himself within other significant or founding leaders in Turkish history by saying, I am here, in front of you with the claim of representing a trust stretching out from Sultan Alparslan to Osman Bey, from Mehmet the Conqueror to Sultan Selim the Stern, from Abdulhamid Han to Gazi Mustafa Kemal. Thus, he is not only one of the leaders in the 100 years of the Turkish Republic but is part of a line of leaders beginning with Sultan Alparslan who led the entrance of Turks to Anatolia with the Battle of Malazgirt in 1071. Moreover, for him, We are at such a critical conjuncture that, with the steps that we take, we are either going to take our place in the forefront of this league or we are going to be faced with the risk of falling back again. This is the task awaiting the leader, one that is so crucial and important that it cannot be undertaken by just any leader. It requires, first and foremost, experience. As proof of his and his party’s level of experience and ability to undertake big and important tasks, he reels off a lengthy list of services provided by the AKP under his leadership in the last 20 years. He gives detailed figures from education, health, transportation, sport etc., such as how AKP has increased the number of classrooms from 343,000 to 612,000, or the number of airports in the country from 26 to 57, or the gross domestic product from 40 billion Lira to 407 billion Lira. Thus, he seeks to close the debate around his way of governance and leadership by depoliticising the discussion through relying on inarguable statistics. Then, he again draws attention to the experience when at the same time emphasising the inexperience of the opposition in running the country and warns, ‘if we do not continue our way by putting one work on top of another one, it is inevitable that we are going to vanish’. Consequently, as happened during the process that led to the independence of Türkiye and the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago, we are put in a position of choosing between two options, this time presented by Erdoğan: either we are going to do the right thing, or we are going to disappear. Concepts of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ Then, Erdoğan moves onto explaining the ‘spirit’, ‘philosophy’, and ‘essence’ of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ that he suggests as a vision for future not only to Türkiye but to the entire world and humanity. He summaries the Vision with 16 core concepts—namely, sustainability, tranquility, development, values, power, success, peace, science, the ones who are right, efficiency, stability, compassion, communication, digital, production, and future. At the core of those 16 concepts lies the claim and promise to make Türkiye a great regional and global power. Such an assertion consists of two dimensions: first, liberal economic developmentalism, which has a prominent place in the Turkish neoliberal conservative political tradition and is structured around the adjacent concepts such as growth, progress, investment, and enhancing competitive power. For example, Erdoğan says, We will make Türkiye one of the largest global industrial and trade centres by supporting the right production areas based on advanced technology, with high added value, wide markets, and increasing employment. According to Erdoğan, the second dimension of making Türkiye great consists of security and stability. For him, Türkiye has become a global and regional power under his rule thanks to the stability and security guaranteed by the presidential system that came into force in 2017. The continuation of this power, he argues, depends on the maintenance of this security and stability, which is also the guarantee for a continuously prosperous economy and the provision of more work and service to the country. When doing this, for him, we are also responsible for the protection of the values belonging to the whole of humanity—not only the Turkish nation—thus we will also ensure ‘cultural and social harmony’. When considered together with the whole speech, this section conforms with Erdoğan’s understanding of Turkishness articulated with himself and his party. According to the reasoning that we are asked to follow throughout the event, instead of being occupied with the present infrastructural problems of the country that have led to the deterioration of the economy and democracy, our thinking and actions must always be future-oriented. In this respect, for example, what matters is not the present economic situation but the economy in the future as presented in the Vision. We might be starving and struggling to continue our daily lives yet still we should continue growing, competing with our rivals, and building bridges and airports. And such a shining future cannot be arrived through change and but only through security and stability ensured by the leadership of the ‘right man’. Then, he makes a call to ‘everybody’ to contribute to the ‘Century for Türkiye’, to ‘discuss’ it, to ‘put forward proposals’, and to ‘create’ and ‘build’ the vision for a Century of Türkiye together. However, it is not clear how people are to contribute to the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ when our past, present, and path to the future are turned into a destiny where we are not agents but prisoners. In fact, such a tension between the closure and opening of the political space can be witnessed throughout the whole speech. For example, Erdoğan says, Today we have come together for the promise of strengthening the first-class citizenship of the 85 million, except the ones committing hate crimes, crimes of terror and crimes of violence. Here, he draws his antagonistic boundaries around who is included and excluded from the nation. When doing this, he uses tellingly vague terms such as ‘crimes of terror’, which can potentially include anyone depending on how far the definition of ‘terror’ becomes stretched. However, despite this, he promises ‘to put aside all the discussions and divisions that have polarised our country for years and damaged the climate of conversation that is the product of our people's unity, solidarity and brotherhood’. This should be understood as part of his effort to secure his existence in the future of the country as the leader of the whole nation, yet still seeking to do this by persuading people of his way of doing politics. Here, the art does not lie in the total closure and opening of the political space but in the ability to convince people that he is the leader who can do both any time he sees convenient—this is a crucial dimension of Erdoğan’s leadership style. Finally, he ends the speech with an oath as he usually does. He asks around 5,000 people in the hall stand up and repeat his words after him: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be big! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ This is his signature; thus, the speech has been signed. Conclusion Erdoğan’s nationalist political thinking in the context of the centenary of the Turkish Republic is shaped by his particular way of intervening in the political situation and has become part of his strategic action. Erdoğan employs the centenary to assert the continuity of his and his party’s leadership by establishing an analogical continuity between the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago and his leadership today. He turns the kairological moment in the past into his kairological moment for himself. He does this by articulating Turkishness, time and history in a way that enables him to situate himself and his party as the only figure that can guarantee such continuity on which the existence of Turkish nation depends—otherwise, we are going to ‘vanish’. Returning to Benjaminian analysis, Erdoğan takes a ‘tiger’s leap into the past’[16] to establish such continuity, however, as history has also shown us, there is a limit for every jump. [1] I quoted this phrase from the amended version of the Turkish Constitution in 1923 known as Teskilat-i Esasiye Kanunu. The Constitution can be reached from: TESKILATI_ESASIYE.pdf (tbmm.gov.tr), p. 373. [2] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, pp. 264. Jonathan Cape. [3] Smith, J. E. (2002). ‘Time and Qualitative Time’, in Sipiora, P. and Baumlin, J. S. (eds.), p. 47, Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in History, Theory and Praxis, pp. 46-57. State University of New York Press. [4] Ewing, B. (2021). ‘Conceptual history, contingency and the ideological politics of time’, in Journal of Political Ideologies, 26:3, p.271. [5] Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan "Türkiye Yüzyılı" vizyonunu açıkladı - YouTube [6] Freeden, M. (1996). Ideologies and Political Theory. Clarendon Press. [7] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.757. [8] Finlayson, A. (2021). ‘Performing Political Ideologies’, in Rai, S. (ed.) et al, The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance, pp. 471-484. Oxford University Press. [9] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, pp. 751-767. [10] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.751. [11] Martin, J. (2015). Situating Speech: A Rhetorical Approach to Political Strategy. Political Studies, 63:1, pp. 25-42. [12] Adar, S. and Seufert, G. (2021). Turkey’s Presidential System after Two and a Half Years. Stiftung Wissenchaft und Politik (SWP) Research Paper 2. [13] Erdogan ousts Turkey central bank governor days after rate hike | Financial Times [14] 70 percent of Turkey struggling to pay for food, survey finds | Ahval (ahvalnews.com) [15] Turkey's inflation hits 24-year high of 85.5% after rate cuts | Reuters [16] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, p.263. Jonathan Cape. by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

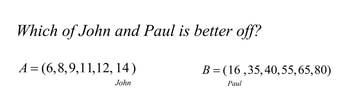

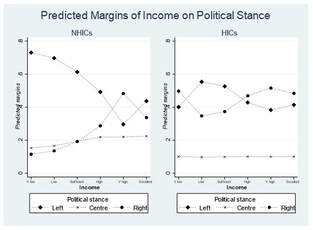

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

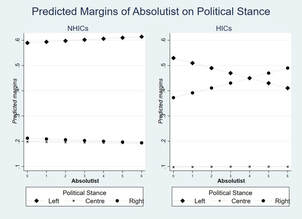

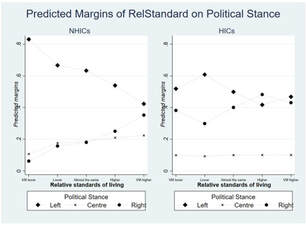

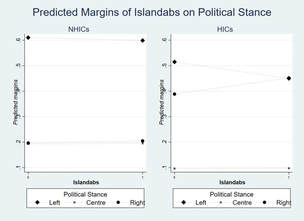

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. by Richard Shorten

Author's Note: The expectation to communicate from personal experience is a crucial driver of modern politics. A recent book I have written, The Ideology of Political Reactionaries, shows how reactionaries have mastered, but subverted, this expectation. Therefore, progressives need to do better. Voice has ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘what’ aspects that need exploring both more explicitly and more creatively. My short discussion distils voice into six foremost elements: argument style, emotional tone, metaphor, prioritising, humour, and personality. Together, these can be wrested into ways for exercising voice in greater (and more meaningful) equality, co-operation, and solidarity: respectively, to reflect, to feel, to connect, to weigh, to confide, and to become energised.