|

30/5/2022 Culture and nationalism: Rethinking social movements, community, and free speech in universitiesRead Now by Carlus Hudson

Although the study of social movements has shown that state institutions are not the only vehicles for societal change, the political forces which emanate from civil society and challenge state authority require theorisation. Near the end of his life, in 1967 Theodor Adorno conceptualised the post-1945 far right as a potent movement with social and cultural attitudes spread widely in West German society and still capable of attracting mass political support.[1] Nazism’s defeat in 1945, the partitioning of Germany and the process and legacy of denazification kept the re-emergence of a similar threat at bay, but the ideology did not disappear. By rejecting a monocausal social-psychological explanation of post-war fascism, Adorno also rejects the pessimistic idea of it as something that people must accept as an inevitable part of living in modern and democratic societies.

Anti-fascists have the agency to change society for the better and they have used it for as long as fascism has existed. Fascist street movements in the UK were defeated in the 1930s and again in 1970s by anti-fascists who mobilised against them in larger numbers at counter-demonstrations. Students took anti-fascism into the National Union of Students (NUS) by voting for the ‘no platform’ policy at the April 1974 conference. The aim of the policy, which built on earlier anti-fascist praxis and has returned in different forms since then, is to deny spaces in student unions to the ideas espoused by fascists and racists, thereby making them less mainstream and limiting the size of the audience reachable by fascist and racist ideologues. By no platforming, students were able to use their unions instrumentally to counter the influence of the extreme right. They were driven by moral revulsion at fascism and racism, a near-universal positive commitment to democratic freedom in society, and in smaller numbers commitments to anti-fascism and anti-racism as social movements and to left-wing politics. The same tactics were later used against homophobic, sexist, and transphobic speakers. Evan Smith’s critically acclaimed study of ‘no platform’ historicises the tactic’s use in the contexts of anti-fascism in Britain and contemporary fear on the right, which he argues is unfounded, for free speech on campuses.[2] Three essential points can be made from Smith’s study about what ‘no platform’ is. Firstly, it is a political decision made against a particular person or group of people. Secondly, those decisions rely on the judgement of the validity of specific demands for restrictions on free speech. Thirdly, ‘no platform’ is a specific type of restriction on free speech that is set apart from the functionally synchronous restrictions put in place by national governments. Governments have legislated limitations on free speech and protections on citizens’ rights to express it in a variety of ways. Free speech is not immutable because political dissidents occupy a contradictory space that leaves them permanently open as targets of state repression and targets of co-optation in the repression of the other. Marxist and anarchist theorists of fascism before 1945 conceptualised it in similar terms to their analyses of states, societies and ideologies: historical formations driven by class interests.[3] As a researcher of student activism, I notice how little can be found in their perspectives about student unions compared to united and popular fronts, revolutionary unions, and vanguard parties. Students’ involvement in political activities and adherence to different ideologies is well-documented. It suggests that student unions affiliated to universities remained peripheral in the organising activities and theoretical interventions of the interwar left. Meanwhile, the growth of free speech as a talking point for the right is unexpected judging by the norm in European and North American history, because of the state repression and censorship that accompanied reaction to political revolutions from the seventeenth to the late twentieth century.[4] While there is no reason to imagine this as any different from state repression outside of European and North American contexts, this chronology can be extended into the twenty-first century with consideration of the rise of new authoritarian governments in Poland, Hungary and Russia.[5] In the twentieth century the British government put limits on the freedom of speech to espouse extreme and hateful views using the Public Order Act 1936 and the Race Relations Acts passed in 1965, 1968 and 1975, but as Copsey and Ramamurthy have shown it has been anti-fascist and anti-racist movements rather than government legislation that has most to counter fascism and racism.[6] In the late 1960s and 1970s, when the National Front (UK) was at the height of its popularity posed a danger with the possibility of winning seats in local elections, it turned its hatred on Black and Asian immigrants under a thin veneer of populist opposition to immigration and criminality. It added Black and Asian people to Nazism’s older enemies—Jews, communists, the Romani, and LGBT people—while it kept its ideological core out of public view.[7] The brief and limited success of the National Front (UK) can be read patriotically as an aberration or an anomaly in a society that was utterly hostile and inhospitable to it. In this view, civil society would eventually have defeated the National Front without the help of anti-fascists or any compromise on free speech at universities. One problem with that interpretation is the racialisation of religious communities after the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the initiation of the War on Terror. Anti-Zionism, the broad-brush term for opposition to Israel, includes anything from criticism of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians on human rights grounds to opposition to Israel’s existence as a country. Left-wing anti-Zionism has received more attention in research about student activism than the anti-Zionism of the extreme right. NUS leaders opposed left-wing anti-Zionist uses of ‘no platform’ in the 1970s, when it was introduced to student unions.[8] After the September 11 attacks, anti-Zionism drew renewed criticism but with greater emphasis on Islamism. Pierre-Andre Taguieff explained the growth of a new type of European anti-Semitism in those terms.[9] In the popular press, a debate about Islamism spilled over into Islamophobic racism. For example, the printing in Charlie Hebdo and Jyllands-Posten of the Mohammed cartoons were acts of mainstreaming Islamophobia in France and Denmark that supported moral panic about Islam. The attack in France on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 had a chilling effect on free speech by contributing to a political climate where it became impossible for ‘those who felt unfairly targeted’ to respond and be heard.[10] Understanding the problem of Muslims being shut out of debates about them, and of being transformed into a debateable question in the first place, requires a consideration of counter-terrorism measures that have marginalised Muslims. In England and Wales, the regulation of charities and the government’s Prevent duty which covers the whole of the UK have added such pressures to the free speech of Muslim students and workers at universities.[11] The positioning of the presence of Muslims in majority White and Christian countries by non-Muslims as a question of cultural compatibility instead of Islamophobia as a racism morally equivalent to anti-Semitism makes it harder for multiculturalism to function there. That said, explanations of the racialisation of religious minorities are incoherent without analysing race. The number of examples that could be given to prove why restrictions on freedom of speech are too harsh in some instances but not harsh enough in others are practically without limit. Anti-fascists who also consider themselves to be communists or anarchists support the administration of justice in ways that are radically different from those in our own societies but which are nonetheless constructed on the same principles that adherents of liberal democracy follow, including freedom of speech. The same statement descends into nakedly racist prejudice when it is used to refer to racialised religious communities. Free speech is at the centre of a cultural conflict. The first two decades of the twenty-first century saw a world economic crisis and the growth of populism and authoritarianism on the right, which according to Francis Fukuyama capitalised on the need for social recognition felt by resentful supporters. As economic inequality grew, identity politics showed an alternative way for people to articulate difference.[12] Identity politics itself changed little through these processes. For example, a prevailing idea among American conservatives is that universities and colleges, like other levels of the education system and other sectors of civil society, are dominated by a left that threats freedom of speech. Dennis Prager sets the stage for a battle for liberal opinion between the left and, he argues, the centre’s natural allies on the conservative right.[13] His views about universities should not be decontextualised from his commentary on religion. In his book written with Joseph Telushkin, Prager explains anti-Semitism using a history of it and an engagement with Jewish identity. They acknowledge the influence of Taguieff’s research on their taking anti-Semitism more seriously as a tangible threat to Jews. Opposing Anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, which they barely distinguish, is a key part of their argument.[14] From another perspective, in his defence of classical liberalism, Fukuyama dedicates a chapter to discussing the global challenges in the twenty-first century to the principle of protecting freedom of speech. One argument he makes is that critical theory and identity politics, when they appear together in the contexts of free speech in higher education and the arts, mistakenly give too much importance to language as an interpersonal mode of political power and structural violence instead of the main targets of leftist critique: the coercive function of institutions and physical violence, capitalism and the state. With universities engaging with a wider definition of what constitutes harm than they have in the past, the parameters for unacceptable speech have widened too.[15] Free speech is no less a political issue today, by which I mean it is a term that people use to express their ideological attachments and experiences of real socio-economic conditions, than it has been in the past. Different conclusions can be drawn from these points. One option is to join socialists and progressives in their fights for equality and social justice through a movement that simultaneously counters the hegemony of right-wing ideology. Another option is to join the right’s defence of freedom of speech on campuses against ‘woke’ students and academics, ‘safer spaces’ and ‘trigger warnings’. Far from simply being bugbears, they are central concepts of opposition for the right in their wider defence of what they value most in their idea of Western civilisation. A more analytical response would be to engage more critically with what identity politics is and engage with the probing questions of how social movements driven by identity politics affect the inclusiveness of societies. Religious, secular and post-secular nationalisms are relevant here because they have a greater determining role than economic interest on political beliefs constructed around identity. However, their influence on politics organised along a left-right axis has never been negligible and the claim that a purely economistic political ideology can exist is highly dubious. Understanding identity politics gives context to the right’s fear for freedom of speech. Another approach is to take the right’s claim at face value and begin to think of freedom of speech as a legislated guarantee for the conditions of voluntary social interaction, without which civil society becomes an impossibility. It would therefore be morally necessary to consider the figuration of the right’s semi-invented enemies. The presentation of these enemies is not necessarily a racist act of subjective violence, and this caveat demarcates a large section of the right from fascists and identifies them as fascism’s serious competitors. At the same time, the right delegitimises its opponents by tarring them as enemies of freedom of speech and therefore a step closer to fascism. What these examples show is how complex an issue freedom of speech at universities is. Freedom of speech must be defined in recognition of that complexity because we are at the greatest risk of losing this freedom when we express ourselves under assumptions that lead us to oversimplify and decontextualise it. [1] Theodor W. Adorno, Aspects of the New Right-Wing Extremism, trans. Wieland Hoban (Medford: Polity, 2020). [2] Evan Smith, No Platform: A History of Anti-Fascism, Universities and the Limits of Free Speech, (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2020). [3] Dave Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, new and updated edition (London: Pluto Press, 2020). [4] Dave Renton, No Free Speech for Fascists: Exploring ‘No Platform’ in History, Law and Politics (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021), 11-34. [5] Dave Renton, The New Authoritarians: Convergence on the Right (London: Pluto Press, 2019). [6] Nigel Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain, second edition (London; New York: Routledge, 2017), 56; Anandi Ramamurthy, Black Star: Britain’s Asian Youth Movements (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 25. [7] Dave Renton, Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League 1976-1982 (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2019), 14-36. [8] Dave Rich, The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism (London: Biteback Publishing, 2016). [9] Pierre-André Taguieff, Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2004). [10] Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter, Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020), 75-9. [11] Alison Scott-Baumann and Simon Perfect, Freedom of Speech in Universities: Islam, Charities and Counter-Terrorism (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021). [12] Francis Fukuyama, Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition (London: Profile Books, 2018). [13] Jordan B. Peterson, No Safe Spaces? | Prager and Carolla | The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast - S4: E44, YouTube, vol. S4: E44, The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHXxtyUVTGU. [14] Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin, Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism, the Most Accurate Predictor of Human Evil (New York: Touchstone, 2007). [15] Francis Fukuyama, Liberalism and Its Discontents (London: Profile Books, 2022). by Jack Foster and Chamsy el-Ojeili

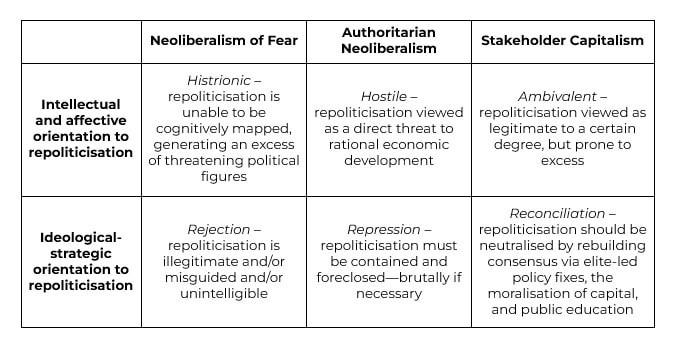

In September 2021, penning his last regular column for the Financial Times after 25 years of writing on global politics, Philip Stephens reflected on a bygone age. In the mid-1990s, an ‘age of optimism’, Stephens writes, ‘the world belonged to liberalism’. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the integration of China into the world economy, the realisation of the single market in Europe, the hegemony of the Third Way in the UK, and the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance presaged a century of ‘advancing democracy and a liberal economic order’. But today, following the financial crash of 2008 and its ongoing fallout, and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘policymakers grapple with a world shaped by an expected collision between the US and China, by a contest between democracy and authoritarianism and by the clash between globalisation and nationalism’.[1] Only five months later, the editors of the FT judged that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had definitively closed the ‘chapter of history opened by the fall of the Berlin Wall’; the sight of armoured columns advancing across the European mainland signals that a ‘new, darker, chapter has begun’.[2] At this juncture, with the all-consuming immediacy of the war in Ukraine, and the widespread appeal of framing the conflict in civilisational terms—Western liberal democracy facing down an archaic, authoritarian threat from the East—it is worth reflecting on some of the currents that flow beneath and give shape to the discourse of Western liberal elites today. In a previous essay, we argued that the leading public intellectuals and governance institutions of Western capitalism have struggled to effectively interpret and respond to the political and economic turmoil first unleashed by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008.[3] We traced out a crisis of intellectual and moral leadership among Western elites in the splintering of (neo)liberal discourse over the past decade-and-a-half—the splintering of what was, prior to the GFC, a relatively consensual ‘moment’ in elite discourse, in which cosmopolitan neoliberalism had reigned supreme. As has been widely argued, the financial crisis brought this period of confidence and self-congratulation to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Both the enduring economic malaise that followed the crash, and the crisis of political legitimacy that has unfolded in its wake, have shaken the intellectual and ideological certitude of Western liberals. All political ideologies experience ‘kaleidoscopic refraction, splintering, and recombination’, as they are adapted to historical circumstances and combined with elements of other worldviews to produce novel formations.[4] However, we argued that the post-GFC period has seen a particularly intense and marked splintering of (neo)liberal discourse into three distinctive but overlapping and intertwining strands or ‘moments’. First, a neoliberalism of fear,[5] which is animated by the invocation of various dystopian threats such as populism, protectionism, and totalitarianism, and which associates the contemporary period with the extremism and instability of the 1930s. Second, a punitive neoliberalism, which seeks to conserve and reinforce existing power relations and institutions of governance.[6] And third, a pragmatic and reconciliatory neo-Keynesianism, oriented above all to saving capitalism from itself. In this essay, we want to expand upon one aspect of this analysis. Specifically, we suggest here that one way in which we can distinguish between these three strands or ‘moments’ is as distinct responses to the repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management in the years following the GFC. Respectively, these responses can be summarised as rejection, repression, and reconciliation (see Table 1, below). Depoliticisation and repoliticisation In our previous essay, we argued that the 1990s and early 2000s were marked by the predominance of cosmopolitan neoliberalism as a successful project of intellectual and moral leadership, the moment of the ‘end of history’ and ‘happy globalisation’. In this period, we saw the radical diminution of economic and social alternatives to capitalism, the colonisation of ever more spheres of social life by the market, the transformation of common sense around the proper relationship between states and markets, the public and the private, equality and freedom, the community and the individual, and the institutionalisation of post-political management, or what William Davies has called ‘the disenchantment of politics by economics’.[7] Of this last, neoliberalism, as both a political ideology and a set of institutions, has always been oriented to the active depoliticisation and indeed dedemocratisation of ‘the economy’ and its management—what Quinn Slobodian calls the ‘encasement’ of the market from the threat of democracy.[8] In practice, this has been pursued in two primary ways. First, it has been accomplished via the legal and institutional insulation of ‘the economy’ from democratic contestation. Here, the delegation of critical public policy decisions to unelected, expert agencies such as central banks and the formulation of rules-based economic policy frameworks designed to narrow political discretion are emblematic. Second, this has been buttressed by ideological appeals to the constraints placed upon domestic economic sovereignty by globalisation and the necessity of technocratic expertise in government—strategies that lay at the heart of the Clinton administration in the US (‘It’s the economy, stupid!’) and the Third Way of Tony Blair in the UK. Economic management was to be left to Ivy League economists, central bankers, and the financial wizards of Wall Street and the City. The so-called ‘Great Moderation’—the period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that was characterised by low macroeconomic volatility and sustained, albeit unspectacular, growth in most advanced economies—lent credence to these ideas. The hubris of elites in this period should not be underestimated. As Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the influential Bank for International Settlements, put it to an audience of European financiers in 2019, ‘During the Great Moderation, economists believed they had finally unlocked the secrets of the economy. We had learnt all that was important to learn about macroeconomics’.[9] And in his ponderous account of how global capitalism might be saved from the triple-threat of financial instability, Covid-19, and climate change, former governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney recalls ‘how different things were’ prior to the credit crash—a period of ‘seemingly effortless prosperity’ in which ‘Borders were being erased’.[10] The GFC catalysed both an epistemological crisis in mainstream economics, and, after some delay, the rise of anti-establishment political forces on both the left and the right. The widespread failure to reflate economic development in the wake of the crisis and the punishing effects of austerity in the UK and the Eurozone, and at the state level in the US, only exacerbated the problem. Over the past decade-and-a-half, questions of economic development, of who gets what, and of who should be in charge, have come back on the table. How have Western elites responded? Rejection One dominant response to this repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management has been to invoke a host of dystopian figures—populism, nationalism, political extremism, protectionism, socialism, and totalitarianism—all of which are perceived as threats to the stability of the open-market order, to economic development, and to a thinly defined ‘liberal democracy’. This is the neoliberalism of fear Four years prior to the election of Donald Trump, the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks’ assessment was already grimly warning that the ‘seeds of dystopia’ were borne on the prevailing winds of ‘high levels of unemployment’, ‘heavily indebted governments’, and ‘a growing sense that wealth and power are becoming more entrenched in the hands of political and financial elites’ following the GFC.[11] In 2013, Eurozone technocrats were raising cautious notes around the ‘renationalisation of European politics’.[12] By 2015, Martin Wolf, long-time economics columnist for the FT, was informing his readers that ‘elites have failed and, as a result, elite-run politics are in trouble’.[13] This climate of fear reached fever-pitch in 2016, with the shocks delivered by the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, and again in January 2021, with mounting fears that President Biden’s inauguration would be blocked by a truculent Republican party. The utopian world of the long 1990s, in which globalisation was ‘tearing down barriers and building up networks between nations and individuals, between economies and cultures’, in the words of Bill Clinton, has thus disappeared precisely as ‘the economy’ and its management began to be repoliticised.[14] Two aspects of this often-histrionic neoliberalism of fear stand out. First, we see a striking inability to cognitively map the repoliticised terrain. Rather than serious attempts to map out why and in what ways repoliticisation is occurring, this strand or ‘moment’ is characterised by a reliance on a set of questionable historical analogies, above all the 1930s and the disasters of totalitarianism. Second, extraordinary weight is given over to these threats and fears, and there is a corresponding absence of serious attempts to construct a new ideological consensus. Instead, repoliticisation is countered in a language that is defensive, hectoring, and dismissive. For Wolf, populist forces have organised to ‘muster the inchoate anger of the disenchanted and the enraged who feel, understandably, that the system is rigged against ordinary people’.[15] In like fashion, former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, reflecting on his role in resolving the GFC, writes that in crises, ‘fear and anger and ignorance’ clouds the judgement of both the public and their representatives and impedes sensible policymaking; it is essential, in times of crisis, that decisions are left to coldly rational technicians.[16] Musing on the integration backlash in the EU, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, noted that while ‘protectionism is society’s natural response’ to unchecked market forces, it is crucial to ‘resist protectionist urges’, and this is the job of enlightened technocrats and politicians, who must hold back the populist forces threatening to roll back market integration.[17] In other words, while recognising that a rampaging globalisation has driven social and political unrest, within this neoliberalism of fear the masses are viewed as too capricious and ignorant to be trusted; the post-GFC malaise, while frightening and disorienting, will certainly not be solved by more democracy. Repression Closely related to, and overlapping with, this neoliberalism of fear is the second core strand or ‘moment’, that of a punitive and coercive neoliberalism. If the neoliberalism of fear can be understood as a dismissive overreaction to repoliticisation, this second strand represents a more direct and focused attempt to manage this new, more unstable, and more contested political economy. Fears of deglobalisation, of protectionism, of fiscal recklessness are also prominent in this line of argument; however, equally prominent are the necessary solutions: strengthening the rules-based global order, ongoing flexibilisation and integration of labour and product markets—particularly in the EU—and a harsh but altogether necessary process of fiscal consolidation. The problem of public debt has, of course, been one of the major battlegrounds here. Preaching the necessity of fiscal consolidation at the elite Jackson Hole conference in 2010, for example, Jean-Claude Trichet raised the cautionary tale of Japan, a country that ‘chose to live with debt’ in the 1980s and suffered a ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s as a result.[18] These concerns were widely echoed in the financial press and by international policy organisations; here, the threat of market discipline was also consistently evoked as justification for fiscal retrenchment and punishing austerity. As former IMF economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff infamously warned, prudent governments pay down public debt, because ‘market discipline can come without warning’.[19] Much has been made of the punitive, moralising, and post-hegemonic dimensions of this discourse.[20] However, it is worth bearing in mind that there are also genuine attempts to match the policy prescriptions associated with this more authoritarian and coercive neoliberalism—fiscal austerity, enhanced fiscal discipline and surveillance, structural adjustment, rules-based economic governance—with a positive vision of the political economy that these policies will deliver: economic growth, global economic stability, a route out of the post-GFC doldrums. Viewed in this way, the key ideological thrust here seems to be less that of punishment for punishment’s sake than it is of the deliberate repression and foreclosure of repoliticisation. Pace the classical neoliberal thinkers, the driving logic is that economic development and economic management are far too important to be left to democracy, which is altogether too fickle and too subject to capture by interest groups to be trusted. The upshot? Austerity, flexibilisation, the strengthening of the elusive rules-based global order: all this must be pushed through regardless of dissent. As with any ideological formation, shutting down alternative arguments is also important. As one speaker at the Economist’s 2013 ‘Bellwether Europe Summit’ put it, ‘the political challenge’ to structural adjustment ‘comes not from the process of adjustment itself. People can accept a period of hardship if necessary. It comes from the belief that there are better alternatives available that are being denied’.[21] In these ways, this second strand or ‘moment’ is directly hostile to the return of the political: less a hurried and defensive pulling-up of the drawbridge, as in the neoliberalism of fear, than a concerted counterattack. Reconciliation While this punitive and coercive neoliberalism seeks to repress repoliticisation by further insulating ‘the economy’ and its management from democratic interference, the third main strand of post-GFC (neo)liberal discourse responds to repoliticisation in a more measured way. In our previous writing on this issue, we referred to this strand or ‘moment’ as a pragmatic neo-Keynesianism, which promotes technocratic policy fixes aimed at lightly redistributing wealth and rebuilding the social contract. Over the past couple of years, we suggest, these more reconciliatory energies have coagulated into a relatively coherent ideological project, that of stakeholder capitalism.[22] Simultaneously, aided by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism of the 2010s has been discredited and has largely vanished from the pages of the financial press, the policy recommendations of the major international organisations, and the books and columns of Western public intellectuals. Thus, we use the term stakeholder capitalism to refer to the recent ideological shift in the Western policy establishment, among public intellectuals, and in business and high finance, that centres around the push for more ‘socially responsible’ corporations, for ‘green finance’, and for the re-moralisation of capitalism. By 2019, this shift was gathering momentum. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz implored readers of the New York Times to help build a ‘progressive capitalism’, ‘based on a new social contract between voters and elected officials, between workers and corporations, between rich and poor, and between those with jobs and those who are un- or underemployed’.[23] The FT launched its ‘New Agenda’, informing its readers that ‘Business must make a profit but should serve a purpose too’.[24] The American Business Roundtable, the crème de la crème of Fortune-500 CEOs, issued a new ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’, in which it revised its long-standing emphasis on promoting shareholder-value maximisation. Rather than narrowly focusing on returning profit to their shareholders, it now claims that corporations should ‘focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone—investors, employees, communities, suppliers, and customers’.[25] Similarly, the WEF launched its 50th-anniversary ‘Davos Manifesto’ on the purpose of a company, promoting the development of ‘shared value creation’, the incorporation of environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into company reporting and investor decision-making, and responsible ‘corporate global citizenship […] to improve the state of the world’.[26] And no lesser figure than Jaime Dimon, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, noted in his 2019 letter to shareholders that ‘building shareholder value can only be done in conjunction with taking care of employees, customers and communities. This is completely different from the commentary often expressed about the sweeping ills of naked capitalism and institutions only caring about shareholder value’.[27] Now, in early 2022, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, has announced that it will be launching a ‘Center for Stakeholder Capitalism’ in the near future.[28] The term ‘stakeholder management’ was originally coined by the business-management theorist Edward Freeman in the 1980s,[29] but the roots of this discourse go back to the dénouement of the first Gilded Age, where some business leaders began to promote the idea of the socially responsible corporation as a means of outflanking working-class discontent during the Great Depression.[30] The concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ then became popular in the 1990s, associated above all with the Third Way of New Labour.[31] Today, the discourse of stakeholder capitalism has been resurrected and updated, we suggest, in direct response to the repoliticisation of the economy and its management and the failure of authoritarian neoliberalism to provide a way out of the post-2008 quagmire. At the root of this rebooted version of stakeholder capitalism is an argument for the re-moralisation of capitalism in the interests of social cohesion and long-term sustainability. To be sure, there remains a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, consumer choice, and so on. But there is also a recognition of—or at least the payment of lip service to—the fact that a rampaging globalisation and widespread commodification has undermined social stability and cohesion. Thus, in contrast to the second strand or ‘moment’ of post-GFC (neo)liberalism, stakeholder capitalism seeks to deal with the repoliticisation of the economy and its management by establishing a more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. To establish a more inclusive capitalism means making some relatively significant shifts in economic policy. ‘[T]argeted policies that achieve fairer outcomes’ are the order of the day.[32] A more fiscally active state and investment in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D are all called for. So too is an expanded social-welfare safety net, primarily in the form of active labour-market policies. And above all, stakeholder capitalism is about tackling the green-energy transition, which presents, for boosters of a private-finance-led transition, ‘the greatest commercial opportunity of our time’.[33] This means ‘smart’ state intervention to steer and ‘derisk’ private investment.[34] Cultural reform, economic education, and democratic renewal are also viewed as important enabling features of this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. Here, policymakers must lead from the front, finding ways to better communicate with, and to educate, citizens and to foster consensus. In these respects, if the ‘moment’ of punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism was characterised by the repression of repoliticisation, then stakeholder capitalism seeks reconciliation. But while the legitimacy of democratic dissatisfaction is broadly recognised, and while there is a place for ‘more democracy’ in the discourse of stakeholder capitalism, this is democracy conceptualised not as the meaningful contestation of the distribution of power and resources, but as a relentless machine for building consensus. Opposing value systems and fundamental conflicts over the distribution of resources do not exist, only ‘stakeholder engagement’ oriented to revealing the ‘public interest’ or the preferences of ‘society’ at large. Exponents of stakeholder capitalism call for more education on how the economy works and emphasise the need to ‘listen’ more attentively to the citizenry. But the intention behind such endeavours is to develop or fortify consensus around already-existing institutions, or at best to tweak them at the margins. In these respects, there is an ambivalence running through this third—and perhaps now dominant—strand or ‘moment’: the mistrust of democracy, made explicit in the neoliberalism of fear and its authoritarian counterpart, is never completely out of the frame. Table 1: Rejection, repression, and reconciliation Horizons Despite its obvious limitations from the normative point of view of radical or even social democracy, the (re)emergent ideological formation of stakeholder capitalism does, we suggest, represent a relatively coherent attempt at rebuilding ideological consensus in Western societies. After years of intellectual and moral disorganisation, the rise to dominance of stakeholder capitalism among the policy establishment, high finance, some liberal intellectuals, and the financial press perhaps signals the reestablishment of intellectual and ideological discipline among elites. But it seems unlikely that this line of approach will bear fruit in the long run; the dysfunctions of the (neo)liberal world order—spiralling inequality and oligarchy, post-democratic withdrawal and outrage, resurgent nationalism, and anaemic, debt-dependent economic growth—run deep. More immediately, the war in Ukraine, and the unprecedented financial and economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers, threatens to once again reorder the ideological terrain and to intensify the shift away from globalisation. Perhaps the dominant response among (neo)liberal commentators thus far has been to frame the conflict as the first battle in a coming war for the preservation of liberal democracy: we are seeing the return of a more ‘muscular’ liberalism, reminiscent of the early years of the War on Terror.[35] Indeed, throughout modern history, war has served to restore liberalism’s ideological vigour; the conflict in Ukraine may yet prove to be a shot in the arm. [1] P. Stephens, ‘The west is the author of its own weakness’, Financial Times, 30 September 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9779fde6-edc6-4d4c-b532-fc0b9cad4ed9 [2] The Editorial Board, ‘Putin opens a dark new chapter in Europe’, Financial Times, 25 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a69cda07-2f63-4afe-aed1-cbcc51914105 [3] J. Foster and C. el-Ojeili, ‘Centrist Utopianism in Retreat: Ideological Fragmentation after the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 2021. [4][4] Q. Slobodian and D. Plehwe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian, and P. Mirowski (Eds), Nine Lives of Neoliberalism (London: Verso, 2020), p. 3. [5] N. Schiller, ‘A liberalism of fear’, Cultural Anthropology, 27 October 2016, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-liberalism-of-fear [6] W. Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’, New Left Review, 101 (2016), pp. 121-134. [7] W. Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty, and the Logic of Competition, revised edition (London: Sage, 2017). [8] Q. Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018). The reduction of essentially political problems to their economic dimension is a long-standing feature of liberalism as such and is therefore not an original aspect of neoliberalism; it is, however, particularly pronounced in the latter. [9] C. Borio, ‘Central banking in challenging times’, speech at the SUERF Annual Lecture, Milan, 2019. [10] M. Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 151. [11] World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2012 (Geneva: WEF, 2012), pp. 10, 19. [12] B. Cœuré, ‘The political dimension of European economic integration’, speech at the Ligue des droits de l’Homme, Paris, 2013. [13] M. Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What We Have Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 382. [14] William Clinton, ‘President Clinton’s Remarks to the World Economic Forum (2000)’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOq1tIOvSWg [15] Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks, p. 383. [16] T. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises (London: Random House, 2014), p. 209. [17] M. Draghi, ‘Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2017. [18] J-C. Trichet, ‘Central banking in uncertain times – conviction and responsibility’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2010. [19] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times, 28 January 2010. [20] See, for example, Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’. [21] J. Asmussen, ‘Saving the euro’, speech at the Economist's Bellwether Europe Summit, London, 2013. [22] J. Foster, ‘Mission-oriented capitalism’, Counterfutures 11 (2021), pp. 154-166. [23] J. Stiglitz, ‘Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron’, New York Times, 19 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [24] Financial Times, ‘FT sets the agenda with a new brand platform,’ Financial Times, 16 September 2019, https://aboutus.ft.com/press_release/ft-sets-the-agenda-with-new-brand-platform [25] Business Roundtable, ‘Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”’, 19 August 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [26] World Economic Forum, ‘Davos Manifesto 2020: The universal purpose of a company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’, 2 December 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/davos-manifesto-2020-the-universal-purpose-of-a-company-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/ [27] J. Dimon, ‘Annual Report 2018: Chairman and CEO letter to shareholders’, 4 April 2019, https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm?a=1 [28] L. Fink, ‘Larry Fink’s 2022 letter to CEOs: The power of capitalism’, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter [29] See E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984). [30] J. P. Leary, Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018), pp. 162-163. [31] For an early statement, see W. Hutton, The State We’re In (London: Random House, 1995). Freeman also wrote on the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ in the 1990s. It is notable that the drive to develop this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism is made in the absence of, and often disdain for, the key conditions that enabled Western social democracy to (briefly) thrive—namely, a more autarkic global political economy, mass political-party membership, high trade-union density, the ideological threat posed by Soviet communism, a more coherent and engaged public sphere, and stronger civil-society institutions. Further, exponents of stakeholder capitalism retain a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, and so on. For these reasons, we suggest that its closest ideological cousin is the Third Way. [32] B. Cœuré, ‘The consequences of protectionism’, speech at the 29th edition of the workshop ‘The Outlook for the Economy and Finance’, Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 2018. [33] Carney, Value(s), p. 339. [34] D. Gabor, ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52(3) (2021), pp. 429-459. [35] M. Wolf, ‘Putin has reignitied the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy’, Financial Times, 2 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed