by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. by Emily Katzenstein

Recent years have seen successive waves of “statue wars”[1]—intense controversies over the visible traces of European colonialism in built commemorative landscapes. The most recent wave of controversies about so-called “tainted” monuments[2]—monuments that honour historical figures who have played an ignominious role in histories of slavery, colonialism, and racism—occurred during the global wave of Black Lives Matter protests that started in reaction to the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020. During a summer of global discontent, demonstrators famously toppled statues of Jefferson Davis (Richmond, Virginia), and Edward Colston (Bristol), beheaded a Columbus statue (Boston), and vandalised statues of King Leopold II (Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent), Otto von Bismarck (Hamburg), Winston Churchill (London), and James Cook (Melbourne), to name just a few examples.

These spectacular events sparked heated public debates about the appropriateness and permissibility of defacing, altering, or permanently removing “contested heritage”.[3] These public debates have also led to a renewed interest in questions of contested monuments and commemoration in political theory and political philosophy.[4] So far, however, this emergent debate has focused primarily on normative questions about the wrong of tainted commemorations and the permissibility of defacing, altering, or removing monuments.[5] Engagement with the political-sociological and aesthetic dimensions of monuments, monumentality, and commemoration, including their relationship to political ideologies and subjectivities, by contrast, has remained relatively thin in recent debates about commemoration and contested monuments in political theory. This means that crucial questions about the role of commemorative landscapes in political life and in the constitution of political subjectivities have remained underexplored. For example, there has been only a relatively superficial reconstruction of the ideological stakes of the debate over the fate of contested colonial monuments. Similarly, while there have been several powerful defences of vandalising and defacing “tainted commemorations,”[6] the literature in political theory and political philosophy has not yet engaged fully with innovative aesthetic strategies for contesting colonial monuments through decolonising artistic practices. This series, Contested Memory, Contesting Monuments, seeks to curate a space in which emergent debates about monuments and commemoration in political theory can be in conversation with debates about the politics of the built commemorative landscape in political science, anthropology, sociology, and area studies that explore political-sociological and aesthetic dimensions of monuments and commemoration. Importantly, it also seeks to facilitate a direct exchange of perspectives between scholars of monuments and commemoration in the academy, on the one hand, and memory activists and artists who are actively involved in today’s politics of memory and monuments, on the other. This is intended to be an open-ended series but we start with a wide-ranging series of inaugural contributions. In the first contribution to the series, Moira O’Shea traces the history of contesting Confederate monuments in the US and reflects on our relationship to the past. Upcoming contributions include an interview with Yolanda Gutierrez, a Mexican-German performance artist, and the founder of Bismarck Dekolonial, in which we discuss the realities of attempting to decolonise the built environment through artistic interventions; Chong-Ming Lim’s exploration of vandalising tainted commemorations; Sasha Lleshaj’s Sound Monuments, which reflects on very idea of monumentality, and connects struggles over ‘contested heritage’ to political contestations of ‘soundscapes’; and Tania Islas Weinstein and Agnes Mondragón analyses of the political uses and abuses of public art in contemporary Mexican politics. [1] Mary Beard, "Statue Wars," Times Literary Supplement, 13.06.2020 2015. [2] Chong‐Ming Lim, "Vandalizing Tainted Commemorations," Philosophy & Public Affairs 48, no. 2 (2020). [3] Joanna Burch-Brown, "Should Slavery's Statues Be Preserved? On Transitional Justice and Contested Heritage," Journal of Applied Philosophy 39 no. 5 (2022). [4] Helen Frowe, "The Duty to Remove Statues of Wrongdoers," Journal of Practical Ethics 7, no. 3 (2019); Johannes Schulz, "Must Rhodes Fall? The Significance of Commemoration in the Struggle for Relations of Respect," Journal of Political Philosophy 27, no. 2 (2019); Burch-Brown, "Should Slavery's Statues Be Preserved? On Transitional Justice and Contested Heritage."; Lim, "Vandalizing Tainted Commemorations."; Macalester Bell, "Against Simple Removal: A Defence of Defacement as a Response to Racist Monuments," Journal of Applied Philosophy 39 no. 5 (2021). [5] Daniel Abrahams, "Statues, History, and Identity: How Bad Public History Statues Wrong," Journal of the American Philosophical Association, First View , pp. 1 - 15 (2022). [6] Bell, "Against Simple Removal: A Defence of Defacement as a Response to Racist Monuments."; Ten-Herng Lai, "Political Vandalism as Counter-Speech: A Defense of Defacing and Destroying Tainted Monuments," European Journal of Philosophy 28, no. 3 (2020); Lim, "Vandalizing Tainted Commemorations." by Lenon Campos Maschette

Over the past few centuries, the concept of civil society has shifted a few times to the centre of political debate. The end of the 20th century witnessed one of these moments. From the 1980s, civil society resurfaced as a central political idea, an important conceptual tool to address all types of social and political problems as well as describe social formations. At the end of the last century, a general criticism of the state and its inability to solve key social problems and the search for a ‘post-statist’ politics were problems shared by several countries that allowed the civil society debate to spread globally.[1]

In Britain, ideologies of the right had an important role in this movement. From the 1980s, all the discussions around community and citizen participation have to be analysed, at least in part, within the context of how the nature and function of the state were being reshaped, especially through the changes proposed by right-wing intellectuals and politicians. This tendency is even more noticeable within the British Conservative Party. In one of the most important works on the British Conservative Party and civil society, E. H. H. Green argues that the Conservative Party’s state theory throughout the 20th century was more concerned with the effectiveness of civil society bodies than with the role of the state.[2] Therefore, it is a long tradition that was continued and reinforced by Thatcher’s leadership. As I argued in another work, the Thatcher government redefined the concept of citizenship and placed civil society at the centre of its model of citizenship.[3] In this new article, I want to compliment that and argue that civil society had vital importance in Thatcher’s project. From this perspective, the Thatcher government redefined the idea of civil society, regarded as the space par excellence for citizenship—at least in the way Thatcherism understood it. Thatcherism attributed to civil society and its institutions a central role in the socialisation of individuals and the transmission of traditional values. It was the place par excellence of individual moral development and, consequently, citizenship. Thatcherism and civil society The Conservative Party never abandoned the defence of civil associations as both important institutions to deliver public services and essential spaces for maintaining and transmitting shared values. Throughout the post-WW2 period, the Party continuously emphasised the importance of the diversity of voluntary associations, and as a response to the growing dissatisfaction with statutory welfare, support for more flexible, dynamic, and local voluntary provision became part of its 1979 manifesto. As already mentioned, civil society had virtually disappeared from the public debate and Thatcher herself rarely used the term ‘civil society’. However, the idea had a central role within Thatcherism. As the article will show, the Conservatives were constantly thinking about the intermediary structures between individuals and the state, and from these reflections we can try to comprehend how they saw these institutions, their roles, and their relationships. According to the Conservatives, civil society was being threatened by a social philosophy that had placed the state at the centre of social life to the detriment of communities. In fact, civil society had not disappeared, but was experiencing profound changes. In a more affluent and ‘post-materialistic’ society, individuals had turned their attention from first material needs to identities, fulfilment, and greater quality of life. Charities and religious associations had also changed their strategies and came close to the approach and methods of secular and modern voluntary associations, loosening their moralistic and evangelical language and adopting a more political and socially concerned discourse. These are important transformations that are the basis of how the Thatcher government linked the politicisation of these institutions with the demise of civil society. Thatcher always made clear that voluntary associations and civil institutions were central to her ‘revolutionary’ project. The Conservatives under Thatcher regarded the civil institutions as the best means to reach more vulnerable people and the perfect space for participation and self-expression.[4] The neighbourhood, this smallest social ‘unit,’ was more personal and effective than larger and more bureaucratic bodies. Furthermore, civil society empowered individuals by giving them the opportunity to participate in local communities and make a difference. It is noteworthy that Thatcher’s individualism was not synonymous with an atomised and isolated individual. Thatcher did not have a libertarian view about the individuals. As she argued to the Greater Young Conservatives group, ‘there is not and cannot possibly be any hard and fast antithesis between self-interest and care for others, for man is a social creature … brought up in mutual dependence.’[5] According to her, there was no conflict between her ‘individualism and social responsibility,’[6] as individuals and community were connected and ‘personal efforts’ would ‘enhance the community’, not ‘undermine’ it.[7] She believed in a community of free and responsible individuals, ‘held together by mutual dependence … [and] common customs.’[8] Working in the local and familiar, within civil associations and voluntary bodies, individuals, in seeking their own purposes and goals, would also achieve common objectives, discharge their obligations to the community and serve their fellows and God.[9] And here is the key role of civil and voluntary bodies. They were responsible for guaranteeing traditional standards and transmitting common customs. By participating in these associations, individuals would achieve their own interests but also feel important, share values, strengthen social ties, and create a distinctive identity. Thatcherites believed that voluntary associations, charities, and civil institutions had a central position in the rebirth of civic society. These conceptions partly resonated with a conservative tradition that recognised the intermediated structures as institutions responsible for balancing freedom and order. For conservatives, civil institutions and associations have always played a central role within civil society as institutions responsible for socialising and moralising individuals. From the Thatcherite perspective, these ‘little platoons’—a term formulated by Edmund Burke, and used by conservatives such as Douglas Hurd, Brian Griffiths,[10] and Thatcher herself to qualify local associations and institutions—provided people a space to develop a sense of community, civic responsibility, and identity. Therefore, Thatcher and her entourage believed that civil society had many fundamental and intertwined roles: it empowered individuals through participation; it developed citizenship; it was a repository of traditions; it transmitted values and principles; it created an identity and social ties; and it was a place to discharge individuals’ obligations to their community and God. The state—not Thatcherism, nor indeed the market—isolated individuals by stepping into civil society spaces and breaking apart the intermediary institutions.[11] In expanding beyond its original attributions, the state had eclipsed civil associations and institutions. Centralisation and politicisation were weakening ‘mediating structures,’ making people feel ‘powerless’ and depriving individuals of relieving themselves from ‘their isolation.’[12] It was also opening a space for a totalitarian state enterprise. While the state was creating an isolated, dependent, and passive citizenry, the new social movements were politicising every single civil society space, fostering divisiveness and resentment. The great issue here was politicisation. Civil and local spaces had been politicised. The local councils were promoting anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-homophobic agendas, local government and trade unions were encouraging riots and operating ‘to break, defy, and subvert the law’[13] and the Church was ‘failing the people of England.’[14] Neoconservatives[15] drew attention to both the intervention and politicisation from the state but also from social movements such as feminism. As shown earlier, civil society dynamics had changed and new and more politicised movements emerged. John Moore, a minister and another long-term member of Thatcher’s cabinet, complained that modern voluntary organisations changed their emphases from service groups to pressure groups.[16] That is the reason why Thatcher, in spite of increasing grants to the voluntary sector, carefully selected those associations with principles related to ‘self-help and enterprise,’ that encouraged ‘civic pride’ while also discouraging grants to institutions previously funded by left-wing councils.[17] The state and the new social movements had politicised and dismantled civil society spaces, especially the conservatives' two most important civil institutions: the family and the Church. Thatcherism placed the family at the centre of civil society. Along with the ‘surrounding community of friends and neighbours,’ the family was a key institution to ‘individual development.’[18] This perspective dialogued with a conservative idea that came directly from Burke and placed the family at the core of civil society. From a Burkean perspective, the family was an essential institution for civilisation as it had two fundamental roles: acting as the ‘bulwarks against tyranny’ and against the ‘perils of individualism.’[19] The family was important as the first space of socialisation and affection and, consequently, the first individual responsibility. Within the family, moral values were kept and transmitted through generations, preventing degeneration and dependence. Thatcher’s government identified the family as the ‘very nursery of civil virtue’[20] and created the Family Policy Group to rebuild family life and responsibility. The family also had a decisive role in checking the state authority. Along with neoconservatives, Thatcherites believed that the welfare state and ‘permissiveness’ had broken down the family and its core functions. From this perspective, the most important civil institution had been corrupted by the state and the new social movements. If Thatcherism dialogued with neoliberalism and its criticism of the state, it was also influenced by conservative ideas of civil society and neoconservative arguments against the new social movements and the welfare state. Despite some tensions, Thatcherism was successful in combining neoliberal and neoconservative ideas. The other main civil institution was the Church. Many of Thatcher’s political convictions were moral, rooted in puritan Christian values nurtured during her upbringing. Thatcher and many of her allies believed that Christianity was the foundation of British society and its values had to be widely shared. The churches were responsible for exercising ‘over [the] manners and morality of the people’[21] and were the most important social tool to moralise individuals. Only their leaders had the moral authority ‘to strengthen individual moral standards’[22] and the ‘shared beliefs’ that provide people with a moral framework to prevent freedom to became something destructive and negative.[23] Thus, the conservatives had the goal of depoliticising civil society. It should be a state- and political-free space. Thatcher’s active citizen was an apolitical one. The irony is that the Thatcher administration made these institutions even more dependent on state funding. Thatcherism was incapable of comprehending the new dynamics of civil institutions. The diverse small institutions, mainly composed of volunteer workers, had been replaced by larger, more bureaucratic and professionalised ones closely related to the state. If the state and, consequently, politicians could not moralise individuals—which, in part, explains the lack of a moral agenda in the period of Thatcher’s government, a fact so criticised by the more traditional right, since ‘values cannot be given by the state or politician,’[24] as she proclaimed in 1978—other civil society institutions not only could, but had a duty to promote certain values. The Thatcher government and communities From the mid-1980s, the Conservative Strategy Group advised the party to emphasise the idea of a ‘good neighbour’ as a very distinct conservative concept.[25] The Conservative Party turned its eyes to the issue of communities and several ministers started to work on policies related to neighbourliness. At the same time, Thatcher’s Policy Unit also started thinking of ways to rebuild ‘community infrastructure’ and its voluntary and non-profit organisations. The civil associations more and more were being seen by the government as an essential instrument in changing people’s views and beliefs.[26] As we have seen, it was compatible with the Thatcherite project. However, it was also a practical answer to rising social problems and an increasingly conservative perception, towards the end of the 1980s, that Thatcher’s administration failed to change individual beliefs and civil society actors, groups, and institutions. And then, we begin to note the tensions between Thatcherite ideas and their implications for the community. Thatcherites believed in a community that was first and foremost moral. The community was made up of many individuals brought up by mutual dependence and shared values and, as such, carrying duties prior to rights. That is why all these civic institutions were so important. They should restrain individual anti-social behaviour through the wisdom of shared ‘traditional social norms that went with them.’[27] The community should set standards and penalise irresponsible behaviour. A solid religious base was therefore so important to the moral civil society framework. And here Thatcher was always very straightforward that this religious basis was a Christian one. Despite preaching against state intervention, Thatcher was clear about the central role of compulsory religious education to teach children ‘the difference between right and wrong.’[28] In order to properly work, these communities and its civil institutions should have their authority and autonomy restored to maintain and promote their basic principles and moral framework. And that is the point here. The conservative ‘free’ communities only could be free if they followed a specific set of values and principles. During an interview in May 2001—among rising racial tensions that lead to serious racial disturbances over that year’s spring and summer—Thatcher argued that despite supporting a society comprised of different races and colours, she would never approve of a ‘multicultural society,’ as it could not observe ‘all the best principles and best values’ and would never ‘be united.’[29] Thatcher was preoccupied with immigration precisely because she believed that cultural issues could have negative long-term effects. As she said on another occasion, ‘people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.’[30] Different individuals would work together and keep themselves together only if they shared some basic principles and beliefs. Thatcher’s community was based on common tradition, not consent or contract. Conservatives believed that shared values were essential for social cohesion. That is why a multicultural society was so dangerous from her perspective. Moreover, there is also another implication here. Multiculturalism not only needed to be repulsed because it was regarded as divisive, but also because it presupposes that all cultures have equal value. It was not only about sharing the same values and principles, but also about sharing the right values and principles. And for the conservatives, the British and Christian traditions were the right ones. That is why Christian religious education should be compulsory for everybody, regardless of their ethnic and cultural background. In part, it explains the Thatcher administration’s long fight against local councils and authorities that supported multiculturalism and anti-racist movements. They were seen as a threat to cultural and traditional values as well as national sovereignty. In addition to responding many times with brutal police repression to the 1981 riots—which is in itself a strong state intervention—the government also released resources for urban regeneration and increased the budget of ‘ethnic projects’ in order to control these initiatives. The idea was to shape communities in a given way and direction and create tools for the community to police themselves. The government was seeking ways to change individual attitudes that, according to the Conservatives, were at the root of social problems in the inner cities. Rather than being the consequence of social problems, these attitudes, they argued, were caused by cultural and moral issues, especially in predominantly black communities.[31] In encouraging moderate black leaders, the government was trying to foster black communities that would behave as British middle-class neighbourhoods.[32] Thatcher’s government also tried to shape communities through business enterprises and market mechanisms. In the late 1980s, her government started a bold process of community refurbishment that aimed to revitalise what were regarded as deprived areas. The market was also seen as a part of civil society and a moralising space that encouraged good behaviour. Thatcher’s relationship with the family, the basis of civil society, was also problematic. The Conservatives had a very traditional conception of family. The family was constituted by a heterosexual married couple. If Thatcherites accused new social movements of imposing their worldview on the majority, Thatcher’s government tried to prescribe a ‘natural’ view of family that excluded any type of distinct formation. Furthermore, despite presiding over a decade that saw a rising expansion of women's participation in the workplace and education, Thatcher advanced an idea of community that was based on women's caring role within the family and the neighbourhood. Finally, the Church, regarded as the most important source of morality, was, at first, viewed as a natural ally, but soon would become a huge problem for her government. As with many established British institutions, according to the Conservatives, the Church had been captured by a progressive mood that had politicised many of its leaders and diverted the Church's role on morality. The Church was failing Britain since it had abdicated its primary role as a moral leader. It was also part of a broader attack on the British establishment. Thatcher would prefer to align her government with religious groups that performed a much more ‘valuable role’ than the established Church.[33] The tensions between the Thatcher government's ideas and policies—which blended neoliberal and neoconservative approaches—and its results in practice would lead to reactions on both left and right-wing sides. If Thatcher herself realised that her years in office had not encouraged communities’ growth, the New Labour and the post-Thatcher Conservative Party would invest in a robust communitarian discourse. Tony Blair's Party would use community rhetoric to emphasise differences from Thatcherism, whereas the rise of ideas that focused on civil society, such as Compassionate Conservatism, Civic Conservatism, and Big Society, would be a Conservative response to the Thatcher's 1980s. Conclusion Conventionally, conservatives have treated civil society as a vehicle to rebuild traditional values, a fortress against state power and homogenisation that involved the past, the present and the future generations. Thatcher believed that a true community would be close to the one where she spent her childhood. A small community, composed by a vibrant network of voluntary bodies free from state intervention, in which apolitical and responsible citizens would be able to discharge their religious and civic obligations through voluntary work. These obligations resulted from religious values and individuals' mutual physical and emotional dependence, which imposed responsibilities prior to their rights, derived from these duties rather than from an abstract natural contract. Therefore, the Thatcherite community was, above all, a moral community. Accordingly, it was based on a narrow set of values and principles that was based on conservative British and Christian traditions. In a complex contemporary world of multicultural societies, it is difficult not to see Thatcher's community model as exclusionary and authoritarian. Despite her conservative ideas about neighbourhoods, her government seems to have encouraged even more irresponsible behaviour and community fragmentation. Thatcher seems not to have been able to identify the problems that economic liberalisation policies and strong individualistic rhetoric could cause to the community. Here, the tensions between her neoliberal and neoconservative positions became clearer. As she recognised during an interview, ‘I cut taxes and I thought we would get a giving society and we haven’t.’[34] To conclude, it is interesting to note that the civil society debate emerged in the UK with and against Thatcherism. The argument based on the revitalisation of civil society was used by both left and right-wingers to criticise the Thatcher years.[35] New Labour’s emphasis on communities, post-Thatcher conservatism’s focus on civil society, the emergence of communitarianism and other strands of thought that placed civil society at the centre of their theories; despite their differences, all of them looked to the community as an answer for the 1980s and, at least in part, its emphasis on the free market and individualism. On the other hand, as I have tried to show, Thatcherism was already working on the theme of community and raised many of these issues during the years following her fall. The idea of civil society as the space par excellence of citizenship and collective activities, as the place to discharge individual obligations and as a site of a strong defence against arbitrary state power, were all themes advanced by Thatcherism that occupied a lasting space within the civil society debate. Thatcherism thus also influenced the debate from within, not only through the reaction against its results, but also directly promoting ideas and policies about civil society. [1] Jean Cohen and Andrew Arato, Civil Society and Political Theory (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1997), 71-72. [2] E.H.H. Green, Ideologies of Conservatism. Conservative Political Ideas in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 278. [3] Lenon Campos Maschette, 'Revisiting the concept of citizenship in Margaret Thatcher’s government: the individual, the state, and civil society', Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021). [4] Margaret Thatcher, Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture (‘Liberty and Limited Government 11 January 1996). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/108353. [5] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to Greater London Young Conservatives (Iain Macleod Memorial Lecture, ‘Dimensions of Conservatism’ 4 July 1977). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103411. [6] Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: Harper Collins, 1993), 627. [7] Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Party Conference, 14 October 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation document 107352: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107352. [8] Margaret Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (‘I BELIEVE – a speech on Christianity and politics’ 30 March 1978). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103522. [9] Thatcher, The Moral Basis of a Free Society. Op. Cit. [10] Douglas Hurd had several important roles during Thatcher’s administration, including Home Office. Brian Griffiths was the chief of her Policy Unit from the middle 1980s and one of her principal advisors. [11] Michael Alison, ‘The Feeding of the Billions’, in Michael Alison and David Edward (eds) Christianity & Conservatism. Are Christianity and conservatism compatible? (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990), 206-207; Brian Griffiths, ‘The Conservative Quadrilateral’, Alison and Edward, Christianity & Conservatism, 218; Robin Harris, Not for Turning (London: Corgi Books. 2013), 40. [12] Griffiths, Christianity & Conservatism, 224-234. [13] Margaret Thatcher. Speech to Conservative Party Conference 1985. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106145. [14] John Gummer, apud Martin Durham, ‘The Thatcher Government and “The Moral Right”’, Parliamentary Affair, 42 (1989), 64. [15] American neoconservatives such as Charles Murray, George Gilder, Lawrence Mead, Michael Novak, etc., worked on the social, cultural, and moral consequences of the welfare state and the ‘long’ 1960s. They were also much more active in writing on citizenship issues. These authors had a profound influence on Thatcher’s Conservative Party through the think tanks networks. Murray and Novak, for instance, even attended Annual Conservative Party conferences and visited Thatcher and other Conservative members’ Party. [16] Timothy Raison, Tories and the Welfare State. A history of Conservative Social Policy since the Second World War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990), 163. [17] Geoffrey Finlayson, Citizen, State and Social Welfare in Britain 1830 – 1990 (Oxford, 1994), 376. [18] Douglas Hurd, Memoirs (London: Abacus, 2003), 388. [19] Richard Boyd, ‘The Unsteady and Precarious Contribution of Individuals’: Edmund Burke's Defence of Civil Society’. The Review of Politics, 61 (1999), 485. [20] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to General Assembly to the Church of Scotland, 21 May 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107246. [21] Douglas Hurd, Tamworth Manifesto, 17 March 1988, London Review of Books: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v10/n06/douglas-hurd/douglas-hurds-tamworth-manifesto. [22] Douglas Hurd, article for Church Times, 8 September 1988. THCR /1/17/111B. Churchill Archives, Churchill College, Cambridge University. [23] Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (1978), Op. Cit. [24] Margaret Thatcher, apud Matthew Grimley. Thatcherism, Morality and Religion. In: Ben Jackson; Robert Saunders (Ed.). Making Thatcher’s Britain. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2012), 90. [25] Many meetings emphasised this issue throughout 1986. CRD 4/307/4-7. Conservative Party Archives, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University. [26] ‘Papers to end of July’, 18 June 1987. PREM 19/3494. National Archives, London. [27] Edmund Neill, ‘British Political Thought in the 1990s: Thatcherism, Citizenship, and Social Democracy’, Mitteilungsblatt des Instituts fur soziale Bewegungen, 28 (2002), 171. [28] Margaret Thatcher, ‘Speech to Finchley Inter-church luncheon club’, 17 November 1969. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/101704. [29] Margaret Thatcher, interview to the Daily Mail, 22 May 2001, apud Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher, Vol. III Herself Alone (London: Penguin Books, 2019), 825. [30] Margaret Thatcher, TV Interview for Granada World in Action ("rather swamped"), 27 January 1978. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103485. [31] Oliver Letwin blocked help for black youth after 1985 riots. The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/dec/30/oliver-letwin-blocked-help-for-black-youth-after-1985-riots. [32] Paul Gilroy apud Simon Peplow. Race and riots in Thatcher’s Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 213. [33] Grimley, Op. Cit., 92. [34] Thatcher’s interview to Frank Field, apud Eliza Filby. God & Mrs Thatcher. The battle for Britain’s soul (London: Biteback, 2015), 348. [35] Neill, Op. Cit., 181. by Katy Brown, Aurelien Mondon, and Aaron Winter

Discussion and debate about the far right, its rise, origins and impact have become ubiquitous in academic research, political strategy, and media coverage in recent years. One of the issues increasingly underpinning such discussion is the relationship between the far right and the mainstream, and more specifically, the mainstreaming of the far right. This is particularly clear around elections when attention turns to the electoral performance of these parties. When they fare as well as predicted, catastrophic headlines simplify and hype what is usually a complex situation, ignoring key factors which shape electoral outcomes and inflate far-right results, such as trends in abstention and distrust towards mainstream politics. When these parties do not perform as well as predicted, the circus moves on to the next election and the hype starts afresh, often playing a role in the framing of, and potentially influencing, the process and policies, but also ignoring problems in mainstream, establishment parties and the system itself—including racism.

This overwhelming focus on electoral competition tends to create a normative standard for measurement and brings misperceptions about the extent and form of mainstreaming. Tackling the issue of mainstreaming beyond elections and electoral parties and more holistically does not only allow for more comprehensive analysis that addresses diverse factors, manifestations, and implications of far-right ideas and politics, but is much-needed in order to challenge some of the harmful discourses around the topic peddled by politicians, journalists, and academics. To do so, we must first understand and engage with the idea of the ‘mainstream’, a concept that has attracted very little attention to date; its widespread use has not been matched by definitional clarity or subjected to critical unpacking. It often appears simultaneously essentialised and elusive. Crucially then, we must stress two key points establishing its contingency and challenging its essentialised qualities. The first of these points is therefore that the mainstream is constructed, contingent, and fluid. We often hear how the ‘extreme’ is a threat to the ‘mainstream’, but this is not some objective reality with two fixed actors or positions. They are both contingent in themselves and in relation to one another. In any system, the construction and positioning of the mainstream necessitate the construction of an extreme, which is just as contingent and fluid. These are neither ontological nor historically-fixed phenomena and seeing them as such, which is common, is both uncritical and ahistorical. What is mainstream or extreme at one point in time does not have to be, nor remain, so. The second point is that the mainstream is not essentially good, rational, or moderate. While public discourse in liberal democracies tends to imbue the mainstream or ‘centre’ with values of reason and moderation, the reality can be quite different as is clearly demonstrated by the simple fact that what is mainstream one day can be reviled, as well as exceptionalised and externalised, as extreme the next, and vice versa. Racism would be one such example. As such, the mainstream is itself a normative, hegemonic concept that imbues a particular ideological configuration or system with authority to operate as a given or naturalise itself as the best or even only option, essential to govern or regulate society, politics and the economy. One of the main problems with the lack of clarity over the definition of the mainstream is that its contingency is masked through the assumption that it is common sense to know what it signifies, thus contributing to its reification as something with a fixed identity. Most people (including academics) feel they have a clear idea of what is mainstream; they position themselves according to what they feel/think it is and see themselves in relation to it. We argue that a critical approach to the mainstream, which challenges its status as a fixed entity with ontological status and essentialised ‘good’ and ‘normal’ qualities, is crucial for understanding the processes at play in the mainstreaming of the far right. To address various shortcomings, we define the process of mainstreaming as the process by which parties/actors, discourses and/or attitudes move from marginal positions on the political spectrum or public sphere to more central ones, shifting what is deemed to be acceptable or legitimate in political, media and public circles and contexts. The first aspect we draw attention to is the agency of parties and actors in the matter. Far-right actors are often positioned as agents, either unlocking their own success through internal strategies or pushing the mainstream to adopt positions that would otherwise be considered ‘unnatural’ to it. While we do not wish to dismiss the potential power of far-right actors to exert influence, it is essential to reflect on the capacity of the mainstream to shift the goalposts, especially given the heightened status and power that comes from the assumptions described above. What we highlight as particularly important is that shifts can take place independently and that the far right is not the sole actor which matters in understanding the process of mainstreaming. A far-right party can feel pressured or see an opportunity to become more extreme by mainstream parties moving rightward and thus encroaching on its territory. However, a far-right party can also be made more extreme without changing itself, but because the mainstream moves away from its ideas and politics. The issues associated with the assumed immovability and moderation of the mainstream have led towards a lack of engagement with the role of this group. It is therefore imperative to challenge these assumptions and capture the influence of mainstream elite actors, particularly with regard to discourse, in holistic accounts of mainstreaming. This leads on to one of the core tenets of our framework, which places discourse as a central feature with significant influence across other elements. Too often, discourse has been swallowed up within elections, seen solely as the means through which party success might be achieved, but we argue that it can stand alone and that the mainstreaming of far-right ideas is not something only of interest and concern when it is matched by electoral success. Our framework highlights the capacity of parties and actors from the far right or mainstream (though the latter has greatest influence) to enact discursive shifts that bring far-right and mainstream discourse closer or further from one another. Problematically, we argue, discourse is often seen solely in terms of its strategic effects for electoral outcomes. While we do not deny its importance in this regard, we suggest that discursive shifts may not always be connected in the ways we might expect with elections, and that the interpretation of electoral results can itself feed into the process of normalisation. First, changes at the discursive level do not always lead to a similar electoral trajectory, nor do the effects stop at elections: the mainstreaming of far-right ideas and narratives (including in and as policies) has the potential to both weaken the far right’s electoral performance if mainstream politicians compete over their traditional ground or bolster such parties by centring their ideas as the norm. Whatever the case, we must not lose sight of the effects on those groups targeted in such exclusionary discourse. The impact of mainstreaming does not stop at the ballot box. This feeds into the second key point about elections, in that the way they are interpreted can further contribute to normalisation, either through celebrating the perceived defeat of the far right or through hyping the position of far-right parties as democratic contenders. Certainly, this does not mean that we should not interrogate the reasons behind examples of increased electoral success among far-right parties, but that we must do so in a nuanced and critical manner. We must therefore guard against simplistic conclusions drawn from electoral, but also survey, data which we discuss at length in the article. Accounts of the electorate, often referred to through notions of ‘the people’ or ‘public opinion’, have tended to skew understandings of mainstreaming towards bottom-up explanations in which this group is portrayed as a collection of votes made outside the influence of elite actors. Through our framework, we seek to challenge these assumptions and instead underscore the critical role of discourse through mediation in constructing voter knowledge of the political context. Far from being a prescriptive framework or approach, our aim is to ensure that future engagement with the concept, process and implications of mainstreaming is based on a more critical, rounded approach. This does not mean that each aspect of our framework needs to be engaged with in great depth, but they should be considered to ensure criticality and rigour, as well as avoid both the uncritical reification of an essentially good mainstream against the far right, and the normalisation and mainstreaming of the far right and its ideas. We believe it is our responsibility as researchers to avoid the harmful effects of narrower interpretations of political phenomena which present an incomplete yet buzzword-friendly picture (i.e. ‘populist’ or ‘left behind’), often taken up in political and media discourse, and feed into further discursive normalisation. This brings us to the more epistemological, methodological, and political reason for the intervention and framework proposal: the need for a more reflective and critical approach from researchers, particularly where power and political influence are an issue. It is imperative that researchers reflect on their own role in contributing to the discourse around mainstreaming through their interpretations of related phenomena. This is important in the context of political and social sciences where, despite unavoidable assumptions, interests and influence, objectivity, and neutrality are often proclaimed. Necessarily, this demands from researchers an acknowledgement of their own positionality as not only researchers, but also as subjects within well-established and yet often invisibilised racialised, gendered, and classed power structures, notably those within and reproduced by our institutions, disciplines, and fields of study. by Ben Williams

A burgeoning area of political research has focused on how the ideas and practical politics arising from the theories of the ‘New Right’ have had a major impact and legacy not only on a globalised political level, but also in relation to the domestic politics of specific nations. From a British perspective, the New Right’s impact dates from the mid-1970s when Margaret Thatcher became Leader of the Conservative Party (1975), before ascending to the office of Prime Minister in 1979. The New Right essentially rejected the post-war ‘years of consensus’ and advocated a smaller state, lower taxes and greater individual freedoms. On an international dimension, such political developments dovetailed with the emergence of Ronald Reagan as US President, who was elected in late 1980 and formally took office in early 1981. Within this timeframe, there was also associated pro- market, capitalist reforms in countries as diverse as Chile and China. While the ideas of New Right intellectual icons Friedrich von Hayek[1] and Milton Friedman[2] date back to earlier decades of the 20th century and their rejection of central planning and totalitarian rule, until this point in time they had never seen such forceful advocates of their theories in such powerful frontline political roles.

Thatcher and Reagan’s explicit understanding of New Right theory was variable, but they nevertheless successively emerged as two political titans aligned by their committed free-market beliefs and ideology, forming a dominant partnership in world politics throughout the 1980s. Consequently, the Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ that had traditionally incorporated shared cultural values and military and security co-operation, reached new heights amidst a decade very much dominated by New Right ideology. However, as we now look back over forty years on, debate has arisen as to what extent the ideas and values of the New Right are still relevant in the context of more contemporary political events, namely in relation to how the free market can appropriately react to major global crises. This has been notably applied to how various governments have reacted to both the 2007–8 global economic crash and the ongoing global Covid-19 pandemic, where significant levels of state intervention have challenged conventional New Right orthodoxies that ‘the free market knows best’. The New Right’s effect on British politics (1979-97) In my doctoral research into the evolution of contemporary Conservative Party social policy, the legacy and impact of the New Right on British politics formed a pivotal strand of the thesis, specifically how the UK Conservative Party sought to evolve both its image and policy agenda from the New Right’s free market economic emphasis into a more socially oriented direction. [3] Yet my research focus began at the tail end of the New Right’s period of hegemony, in the aftermath of the Conservative Party’s most devastating and humiliating electoral defeat for almost 100 years at the 1997 general election.[4] From this perspective of hindsight that looked back on eighteen years of continuous Conservative rule, the New Right’s influence had ultimately been a source of both rejuvenation and decline in relation to Conservative Party fortunes at different points of the electoral and historical cycle. In a positive sense, in the 1970s it appeared to revitalise the Conservative Party’s prospects while in opposition under the new leadership of Thatcher, and instilled a flurry of innovative, radical and eye-catching policies into its successful 1979 manifesto, which in subsequent years would be described as reflecting ‘popular capitalism’. Such policies would form the basis of the party’s accession to national office and consequent period of hegemonic rule throughout the 1980s in particular. The nature of such party-political hegemony as a conceptual term has been both analysed and explained in terms of its rise and fall by Andrew Gamble among others, who identified various core values that the Conservatives had traditionally stood for, namely ‘the defence of the Union, the defence of the Empire, the defence of the Constitution, and the defence of property’[5]. However, in a negative sense, by the mid to late 1990s, as Gamble identifies, the party appeared to have lost its way and had entered something of a post-Thatcher identity crisis, with the ideological dynamic instilled by the New Right’s legacy fatally undermining its previously stable equilibrium and eroding the traditional ‘pillars’ of hegemony’ as identified above. While Thatcher’s successor John Major was inclined to a more social as opposed to economic policy emphasis and between 1990-97 sought to distance himself from some of her harsher ideological policy positions, it was perhaps the case that the damage to the party’s electoral prospects had already been done. Not only had the Conservatives defied electoral gravity and won a fourth successive term in office in 1992, but the party’s broader ethos appeared to have become distorted by New Right ideology, and it became increasingly detached from its traditional instincts for pragmatic moderation located at the political centre, and notably its capacity to read the mood with regards the British public’s instinctive tendencies towards social conservatism, as has been argued by Oakeshott in particular. [6] Critics also commented that the New Right’s often harsh economic emphasis was out of touch with a more compassionate public opinion that was emerging in wider public polling by the mid-1990s, and which expressed increasing concerns for the condition of core public services. This was specifically evident in documented evidence that between ‘1995-2007 opinion polls identified health care as one of the top issues for voters.[7] The New Right’s focus on retrenchment and the free market was now blamed for creating such negative conditions by some, both within and outside the Conservative Party. Coupled with a steady process of Labour Party moderation over the late 1980s and 1990s, such trends culminated in major and repeated electoral losses inflicted on the Conservative Party between 1997 and 2005 (with an unprecedented three general election defeats in succession and thirteen years out of government). The shifting spectrum and New Labour When once asked what her greatest political achievement was, Margaret Thatcher did not highlight her three electoral victories but mischievously responded by pointing to “Tony Blair and New Labour”. It is certainly the case that Blair’s premiership from 1997 onwards was very different from previous Labour governments of the 1960s and 1970s, and arguably bore the imprint of Thatcherism far more than any traces of socialist doctrine. This would strongly suggest that the impact and legacy of the New Right went far beyond the end of Conservative rule and continued to wield influence into the new century, despite the Conservative Party being banished from national office. This was evident by the fact that Blair’s Labour government pledged to “govern as New Labour”, which in practice entailed moderate politics that explicitly rejected past socialist doctrines, and by adhering to the political framework and narrative established during the Thatcher period of New Right hegemony. This included an acceptance of the privatisation of former state-owned industries, tougher restrictions to trade union powers, markedly reduced levels of government spending and direct taxation, and overall, far less state intervention in comparison to the ‘years of consensus’ that existed between approximately 1945-75 (shaped by the crisis experience of World War Two). Most of these policies had been strongly opposed by Labour during the 1980s, but under New Labour they were now pragmatically accepted (for largely electoral and strategic purposes). Blair and his Chancellor Gordon Brown tinkered around the edges with some progressive social reforms and there were steadily growing levels of tax and spend in his later phase in office, but not on the scale of the past, and the New Right neoliberal ‘settlement’ remained largely intact throughout thirteen years of Labour in office. Indeed, Labour’s truly radical changes were primarily at constitutional level; featuring policies such as devolution, judicial reform (introduction of the Supreme Court), various parliamentary reforms (House of Lords), Freedom of Information legislation, as well as key institutional changes such as Bank of England independence. The nature of this reforming policy agenda could be seen to reflect the reality that following the New Right’s ideological and political victories of the 1980s, New Labour had to look away from welfarism and political economy for its major priorities. Conservative modernisation (1997 onwards) Given the electoral success of Tony Blair and New Labour from 1997 onwards, the obvious challenge for the Conservatives was how to respond and readjust to unusual and indeed unprecedented circumstances. Historically referred to as ‘the natural party of government’, being out of power for a long time was a situation the Conservatives were not used to. However, from the late 1990s onwards, party modernisers broadly concluded that it would be a long haul back, and that to return to government the party would have to sacrifice some, and perhaps all, of its increasingly unpopular New Right political baggage. This determinedly realistic mood was strengthened by a second successive landslide defeat to Blair in 2001, and a further—albeit less resounding—defeat in 2005. Key and emerging figures in this ‘modernising’ and ‘progressive’ wing of the party included David Cameron, George Osborne and Theresa May, none of whom had been MPs prior to 1997 (i.e., crucially, they had no explicit connections to the era of New Right hegemony) and all of whom would take on senior governmental roles after 2010. Such modernisers accepted that the party required a radical overhaul in terms of both image and policy-making, and in global terms were buoyed by the victory of ‘compassionate’ conservative George W. Bush in the US presidential election in late 2000. Consequently, ‘Compassionate Conservatism’ became an increasingly used term among such advocates of a new style of Conservative policy-making (see Norman & Ganesh, 2006).[8] My doctoral thesis analysed in some depth precisely what the post-1997 British Conservative Party did in relation to various policy fronts connected to this ‘compassionate’ theme, most notably initiating a revived interest in the evolution of innovative social policy such as free schools, NHS reform, and the concept of ‘The Big Society’. This was in response to both external criticism and self-reflection that such policy emphasis and focus had been frequently neglected during the party’s eighteen years in office between 1979 and 1997.[9] Yet the New Right legacy continued to haunt the party’s identity, with many Thatcher loyalists reluctant to let go of it, despite feedback from the likes of party donor Lord Ashcroft (2005)[10] that ‘modernisation’ and acceptance of New Labour’s social liberalism and social policy investment were required if the party was to make electoral progress, while ultimately being willing to move on from the (albeit triumphant) past. Overview of The New Right and post-2008 events: (1) The global crash (2) austerity (3) Brexit (4) the pandemic During the past few decades of British and indeed global politics, the New Right’s core principles of the small state and limited government intervention have remained clearly in evidence, with its influence at its peak and most firmly entrenched in various western governments during the 1980s and 90s. However, within the more contemporary era, this legacy has been fundamentally rocked and challenged by two major episodes in particular, namely the economic crash of 2007–8, and more recently the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Both of these crises have featured a fundamental rebuke to the New Right’s established solutions as aligned with the culture of the reduced state, as had been cemented in the psyche of governance and statecraft within both Britain and the USA for several decades. In the context of the global economic slump, the immediate and instinctive reaction of Brown’s Labour government in Britain and Barack Obama’s Democrat administration in the USA was to focus on a primary role for the state to intervene and stimulate economic recovery, which entailed that large-scale ‘Keynesian’ government activity made a marked comeback as the preferred means of tackling it. While both such politicians were less ideologically wedded to the New Right pedigree (since they were attached to parties traditionally more of the liberal left), this scenario nevertheless marked a significant crossroads for the New Right’s legacy for global politics. However, once the dust had settled and the economic situation began to stabilise, the post-2010 austerity agenda that emerged in the UK (as a longer-term response to managing the global crash) provided New Right advocates with an opportunistic chance to reassert its former hegemony, given the setback to its influence in the immediate aftermath of 2008. Although Prime Minister David Cameron rejected criticism that austerity marked a reversion to harsh Thatcherite economics, having repeatedly distanced himself from the former Conservative Prime Minister since becoming party leader in 2005, there were certainly similarities in the emphasis on ‘balancing the books’ and reducing the size of government between 2010-15. Cameron argued this was not merely history repeating itself, and sought to distinctively identify himself as a more socially-oriented conservative who embraced an explicit social conscience that differed from the New Right’s primarily economic focus, as evident in his ‘Big Society’ narrative entailing a reduced state and more localised devolution and voluntarism (yet which failed to make his desired impact).[11] Cameron argued that “there was such a thing as society” (unlike Thatcher’s quote from 1987)[12], yet it was “not the same as the state”. [13] Following Cameron’s departure as Prime Minister in 2016, the issue that brought him down, Brexit, could also be viewed from the New Right perspective as a desirable attempt to reduce, or ideally remove, the regulatory powers of a European dimension of state intervention, with the often suggested aspiration of post-Brexit Britain becoming a “Singapore-on-Thames” that would attract increased international capital investment due to lower taxes, reduced regulations and streamlined bureaucracy. It was perhaps no coincidence that many of the most ardent supporters of Brexit were also those most loyal to the Thatcher policy legacy that lingered on from the 1980s, representing a clear ideological overlap and inter-connection between domestic and foreign policy issues.[14] On this premise, the New Right’s influence dating from its most hegemonic decade of the 1980s certainly remained. However, from a UK perspective at least, the Covid-19 pandemic arguably ‘heralded the further relative demise of New Right influence after its sustained period of hegemonic ascendancy’.[15] This is because, in a similar vein to the 2007–8 economic crash, the reflexive response to the global pandemic from Boris Johnson’s Conservative government in the UK and indeed other western states (including the USA), was a primarily a ‘statist’ one. This was evidently the preferred governmental option in terms of tackling major emergencies in the spheres of both the economy and public health, and was perhaps arguably the only logical and practical response available in the context of requiring such co-ordination at both a national and international level, which the free market simply cannot provide to the same extent. Having said that, during the pandemic there was evidence of some familiar neoliberal ‘public-private partnership’ approaches in the subcontracting-out of (e.g.) mask and PPE production, lateral flow tests, vaccine research and production, testing, or app creation, which suggests Johnson’s administration sought to put some degree of business capacity at the heart of their policy response. Nevertheless, the revived interventionist role for the state will possibly be difficult to reverse once the crisis has subsided, just as was the case in the aftermath of World War Two. Whether this subsequently creates a new variant of state-driven consensus politics (as per the UK 1945-75) remains to be seen, but in the wake of various key political events there is clear evidence that the New Right’s legacy, while never being eradicated, certainly seems to have been diluted as the world progresses into the 2020s. How the post-pandemic era will evolve remains uncertain, and in their policy agendas various national governments will seek to balance both the role of the state and the input of private finance and free market imperatives. The nature of the balance remains a matter of speculation and conjecture until we move into a more certain and stable period, yet it would be foolish to write off the influence of the New Right and its resilient legacy completely. [1] Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, (1944) [2] Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, (1962) [3] Ben Williams, The Evolution of Conservative Party Social Policy, (2015) [4] BBC ON THIS DAY | 2 | 1997: Labour routs Tories in historic election (2nd May 1997) [5] Andrew Gamble, The Crisis of Conservatism, New Left Review, (I/214, November–December 1995) [6] Michael Oakeshott, On Human Conduct, (1975) [7] Rob Baggott, ‘Conservative health policy: change, continuity and policy influence’, cited in Hugh Bochel (ed.), The Conservative Party and Social Policy, (2011), Ch.5, p.77 [8] Jesse Norman & Janan Ganesh, Compassionate conservatism- What it is, why we need it (2006), https://www.policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/compassionate-conservatism-june-06.pdf [9] Ben Williams, Warm words or real change? Examining the evolution of Conservative Party social policy since 1997 (PhD thesis, University of Liverpool), https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/11633/1/WilliamsBen_Apr2013_11633.pdf [10] Michael A. Ashcroft, Smell the coffee: A wake-up call for the Conservative Party, (2005) [11] Ben Williams, The Big Society: Ten Years On, Political Insight, Volume: 10 issue: 4, page(s) 22-25 (2019) [12] Margaret Thatcher, interview with ‘Woman’s Own Magazine’, published 31 October 1987. Source: Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689 [13] Society and the Conservative Party - BBC News (9th January 2017) [14] Ben Williams, Brexit: The Links Between Domestic and Foreign Policy, Political Insight, Volume: 9 issue: 2, page(s): 36-39 (2018) [15] Ben Williams, The ‘New Right’ and its legacy for British conservatism, Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021) by Joshua Dight

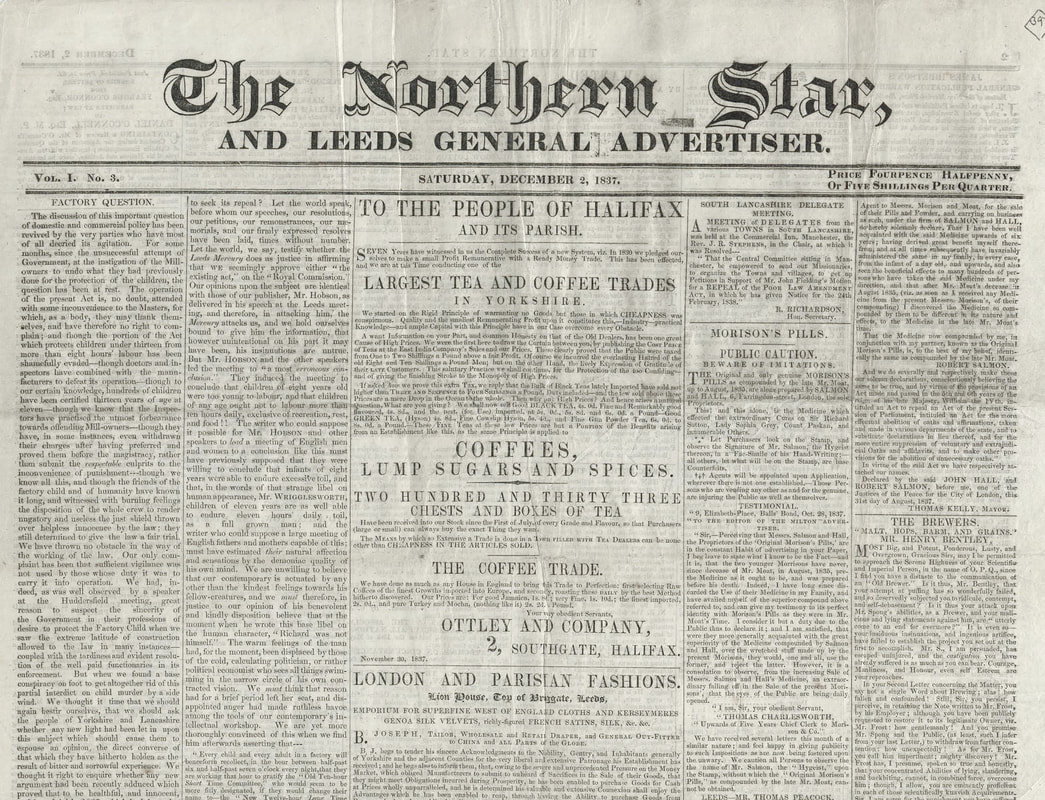

Today, you do not need to go far to locate debates on how to remember the past. From public squares in Glasgow to parks in Australia, questions over statues have been drawn into an open contest. However, this opposition over meaning, and the fight for one reading of history over another is not a new phenomenon. As the title of this piece of writing suggests—How to Read History?—it comes not from the latest newspaper headline, but rather, the past itself. Printed in the Chartist newspaper the Northern Liberator in 1837 at the outset of this mass working- and middle-class movement, the article spoke to the mood of radicals by rejecting established historical narratives that favoured elites. ‘George the third’ for instance, is portrayed as a ‘cold hearted tyrant’ and a ‘cruel despot’, not an uncommon refrain amongst radicals and their chosen lexicon in the unrepresentative political structure of Britain during this period and George III’s reign (1760-1820).[1] Yet, this reimagining does strike upon the issue of locating ‘truths’ within the past, and, by inference, falsehoods. As this article explores, Chartist responses to the existing composition of an anti-radical historical narratives gave them the opportunity to voice their ideology and make commemoration am instrument of their opposition.