by Tania Islas Weinstein and Agnes Mondragón

On July 1st, 2022, Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO) inaugurated the Dos Bocas oil refinery in his home state of Tabasco. The inauguration was a huge publicity coup for the president, who had promised to build the refinery when he first took office.

One of the highlights of the ceremony was the moment when the president unveiled—and fawned over—“La Aurora de México” (1947). La Aurora de Mexico [“The Dawn of Mexico”] is a painting depicting a woman embracing several oil towers as if these were her babies. La Aurora was painted by the late Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. It celebrates the expropriation of foreign oil companies and the nationalisation of the Mexican oil industry in 1938 by then-President Lazaro Cárdenas. Cárdenas appears at the top left of the painting together with Vicente Lombardo Toledano, a labour organiser who helped oil workers unionise. La Aurora harkens back to a product of an era in which the Mexican state actively supported artworks and monuments in public plazas, crossroads, and buildings around the country. That the authoritarian Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) was able to maintain a one-party rule for over seventy years (1929–2000) can, in part, be explained by its ability to tie its political achievements to those of the nation and ideologically interpellate the public into its political project through widespread political communication. The latter included supporting the production of artworks and monuments, many of which were was based on the idea of “art for the people” and, like La Aurora, are characterised by their “narrative style, realist aesthetic, populist iconography, and socialist politics”.[1] AMLO’s public celebration of La Aurora is noteworthy because the Mexican state’s support for the arts and its collaboration with artists has been waning for decades. This decline has accelerated in the wake of the country’s transition to a formal electoral democracy in 2000. Market-oriented reforms have enabled an unprecedented incursion of private corporations and collectors into the art world, who have increasingly supplanted the state as the arts’ main patron.[2] Despite AMLO’s declared opposition to the neoliberal turn in Mexican politics and his nationalist rhetoric that recalls the PRI era, this process has accelerated during his time in power. One of the most surprising characteristics of AMLO’s tenure has been his vocal disdain for artists and intellectuals. Rather than bringing artists back under the aegis of the state, the president has excluded them from his populist project by consistently accusing them of being members of a nebulous, neoliberal elite, and by cutting resources earmarked for artistic institutions as part of his fiscal policy of austeridad republicana or republican austerity.[3] In this context, the display of La Aurora de México during the Dos Bocas refinery’s inauguration is telling. Instead of commissioning a new artwork or monument for the new infrastructure, the government used an old painting that harkens back to the country’s post-Revolutionary authoritarian era and one that celebrates a key political accomplishment that has been framed by official history as a major act of anti-imperialist sovereignty. By displaying this painting at the inauguration, AMLO sought to signify a new era of assertive Mexican sovereignty and nostalgia for a time when Mexico’s economy grew rapidly through a politics of economic nationalisation. As he has argued repeatedly, the refinery will generate a “massive turn” (“un gran viraje”) back from the “neoliberal turn” of the 2000s and 2010s that had made Mexico dependent on imported petroleum.[4] In so doing, it will pave the way for the country to become more economically self-sufficient, which in turn suggests the return of an accompanying economic prosperity. The Aurora itself, meanwhile, is not actually publicly owned. Instead, it belongs to a private owner who loaned the piece to AMLO for the occasion. The Aurora will not remain at the refinery; the painting was returned to the owner as soon as the inauguration was over.[5] AMLO’s one-day exhibition of Siqueiros painting during the Dos Bocas inauguration is paradoxical. On the one hand, AMLO is using the Aurora to signify continuity with a past that is associated with the assertion of Mexican sovereignty and a state-driven economic policy, as a way to signal a break with neoliberal policy. On the other, the brevity of the display, and the fact that the artwork is privately owned also signifies the decline of the Mexican state’s support of public art and thus a continuity with the neoliberal turn rather than a break with it. But what if this interpretation is missing the point? What if rather than focusing on the Siqueiros’ painting as the refinery’s aesthetic and ideological locus we focused on the refinery itself? What if AMLO’s works of infrastructure—of which the Dos Bocas refinery is one among many—are the current administration’s monuments and works of art? Traditionally, monuments have been defined as interventions into the landscape that are built with the purpose of celebrating, commemorating, and glorifying a particular person or event and doing so by conveying a sense of permanence.[6] Extending J.L. Austin’s famous definition, Kaitlin Murphi argues that “monuments effectively function as speech acts: they are public proclamations of certain narratives that are intended to simultaneously reify that narrative and lay claim to the space in which the monument has been placed.”[7] In other words, Murphi maintains, in addition to conveying information, monuments also do things: they usher in or create a new state of affairs simply by laying claim to a space through their presence. While the Siqueiros painting cannot be said to have achieved this, given its impermanent presence, the refinery itself certainly did. Briefly framed by La Aurora, the refinery draws selectively from that celebrated past of oil nationalisation, thus operating like a monument. Indeed, works of infrastructure, much like monuments, possess a sign value that enables them to engage in similar meaning-making and political operations.[8] The Dos Bocas refinery instantiates the ways in which infrastructures may be attributed the symbolic power to effectively function as monuments. Monuments are “focal points of a complex dialogue between past and present,” connecting historical events that are worthy of monumentalisation and spectators who engage with the past via these objects.[9] The relationship that Dos Bocas establishes with that past and its glory is, crucially, mediated through the current political significance that this refinery is expected to have: it is not merely meant to be a repetition of the past, but rather another such moment of revolutionary change. This change, in the president’s words, is marked by a revival of the nationalised oil industry, which had been weakened by neoliberalisation, and thus a recovery of the nation’s lost dignity as a notable producer of oil. The refinery may then be mobilising the past of the Aurora towards its self-fashioning as part of an autonomous aesthetic-political project, making this infrastructure both a monument to the past and to itself. It is also, in many ways, a monument to an economic ideology that once proved to be quite fruitful and an attempt to revive the historical moment in which it did. However, when AMLO inaugurated the refinery, it was not yet ready to be used. Dos Bocas was rushed into being so as to mark a milestone of the current administration, but it was still at least a year away from beginning production. According to several news outlets, only the administrative part of the plant was ready, which represented 30% of the infrastructure. This was not lost on commentators, including prominent critical journalists who described the inauguration as a simulation, forcing AMLO to admit that the refinery was in fact just starting a trial period and would begin operations in earnest in 2023. In a sense, the incomplete—and, in a technical sense, useless—refinery merely constituted the staging of AMLO’s celebration of himself. By inaugurating it before it was finished, the president set the refinery in what Marrero-Guillamón calls a state of suspension, which is not “a temporary phase between the start of a project and its (successful) conclusion, but as a mode of existence in its own right.”[10] Without performing any technical function, the refinery’s power and meaning remain purely aesthetic and discursive, rendering it a monument. By being inaugurated in pieces, infrastructures may work as promises[11] and, therefore, as monuments to those who build them. For AMLO, this was not the first time he used Dos Bocas to stage a political event. On December 9, 2018, barely a week after his inauguration, AMLO laid the first stone at a massive event at the same site. This was marked by the attendance of several high-ranking politicians and a lengthy presidential speech that framed the refinery as part of an urgent solution to a profound crisis in Mexico’s oil industry, caused by waning investment in the state company, Pemex, and the failed effort to open the oil sector to private companies. This event circulated widely: its video was uploaded that same day to AMLO’s personal YouTube account, where it has been streamed over half a million times. The president has also frequently spoken about the refinery during his daily press conferences, showcasing other milestones in its construction, each time setting off discussions in the press and on social media. Following Isaac Marrero-Guillamón, we may see the materiality of Dos Bocas as “redistributed… into multiple instantiations other than its construction, such as exhibitions, technical documents, and public presentations.”[12] We can further extend this redistribution by considering how the extensive media coverage of these public events stretched the refinery’s visibility throughout the public sphere in its capacity as a monumental setting of presidential power. Indeed, a large part of the refinery’s public presence depends not on the concrete and steel of the infrastructure itself, but rather on the circulation of its representations. Given its remote location in a small coastal town in southwest Mexico, the refinery is only connected to most Mexican citizens in these highly indirect ways, much as the gasoline it will (eventually) produce will make its way through the pipelines and into the gas tanks of the vehicles transporting them. Like a monument, the meaning and experiences around Dos Bocas are produced in its abundant “verbal and textual sources.”[13] In official discourse, the refinery is meant to materialise the president’s project of soberanía energética, or energy sovereignty, which, in turn, points to a broader notion of sovereignty—that of an autonomous nation, no longer the object of its commercial partners’ imperial power. More than that, Dos Bocas is meant to be exemplary of the president’s political-economic project, dubbed the Fourth Transformation (4T). Though a precise definition of the 4T is lacking, the president usually invokes it “to describe a revindication of national pride, a political project of aligning the presidency with the popular will, and the creation of a social movement that could do away with the old party system, social inequality, and the economic status quo.”[14] It is meant to match the magnitude of three previous watershed moments in Mexican history: the Independence War (1810–1821), the Guerra de Reforma (Reform War, 1858–1861), and the Revolution (1910–1917). One could perhaps wonder whether the construction of a refinery can in fact be seen as revolutionary in an era of climate change, or whether it in fact constitutes an anticolonial, sovereign act. The refinery’s value rests less (if at all) in its technical function than in its performative capacity. Going back to Murphi’s definition of monuments, Dos Bocas, even in its unfinished stage, does things: it reifies the profound political transformation that AMLO claims to be spearheading and gives AMLO’s discourse concrete reality, thereby conjuring it into being. In so doing, the refinery ushers in a state of affairs that connects multiple temporalities. It draws on a glorified sovereign past and heroic struggle to shape a present that is rendered permanent through the infrastructure’s claim to space. In this scenario, artworks and monuments that celebrate AMLO’s political project are no longer needed, it is the infrastructure itself that does the work. The effectiveness of this infrastructure’s performative power vis-à-vis the old regime’s use of public art remains, however, an open question. To evaluate it, one may need to delve more deeply into the features of the ideological projects that each one is a part of and the conditions that have sustained them. These may include the actors involved in their orchestration and their aims; the distinct ways in which each project’s message has circulated—the former, for instance, privileging visual form in artistic representations of infrastructure, while the latter has resorted to discourse and spectacle; and the ways in which each has been taken up by those they are meant to address; as well as the possibilities for each message to be debated and challenged. But rather than thinking of these two projects separately, as competing endeavours, we must look at their mutual intertwinement as the source of their power. As we saw, La Aurora’s brief display at Dos Bocas’ inauguration meant to transfer its dense meaning to this infrastructure. The refinery’s symbolic force then hinged upon La Aurora’s own (historical) force, which AMLO sought to take in new directions. And, as he did so, he reaffirmed, perhaps reinvigorated, the force of an old, superseded medium, making it part of a new form of political communication. [1] Mary Coffey, How a revolutionary art became official culture (Durham: Duke University, 2012): 22. [2] Daniel Montero, El Cubo de Rubik. Arte Mexicano en los Años 90. (México, RM, 2014). [3] https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFAR_191119.pdf [4] Jon Martín Cullel. “López Obrador defiende la “autosuficiencia” en gasolinas en la inauguración de la refinería de Dos Bocas,” El País (July 1, 2022): https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-07-01/lopez-obrador-defiende-la-autosuficiencia-en-gasolinas-en-la-inauguracion-de-la-refineria-de-dos-bocas.html [5] Leticia Sánchez Medel. “Obra de Siqueiros es exhibida en la inauguración de la Refinería Dos Bocas,” Milenio (July 1, 2022): https://www.milenio.com/cultura/refineria-bocas-exponen-obra-siqueiros-inauguracion [6] James Young, The Texture of Memory (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993). [7] Kaitlin Murphy, “Fear and loathing in monuments: Rethinking the politics and practices of monumentality and monumentalisation,” Memory Studies 14 (6): 1143-1158. [8] Hannah Appel, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta, The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018) [9] Peter Carrier, Holocaust Monuments and National Memory Cultures in France and Germany since 1989 (New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2005, 7). [10] Isaac Marrero-Guillamón, “Monumental Suspension: Art, Infrastructure, and Eduardo Chillida’s Unbuilt Monument to Tolerance,” Social Analysis 64 (16): 28. [11] Appel, Anand, and Gupta 2018; and Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 327-343, 2013. [12] Marrero-Guillamón 2020, 28. [13] Carrier 2006, 22. [14] Humberto Beck, Carlos Bravo Regidor, and Patrick Iber, “Year One of AMLO’s Mexico,” Dissent (Winter 2020): https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/year-one-of-amlos-mexico by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. by Katy Brown, Aurelien Mondon, and Aaron Winter

Discussion and debate about the far right, its rise, origins and impact have become ubiquitous in academic research, political strategy, and media coverage in recent years. One of the issues increasingly underpinning such discussion is the relationship between the far right and the mainstream, and more specifically, the mainstreaming of the far right. This is particularly clear around elections when attention turns to the electoral performance of these parties. When they fare as well as predicted, catastrophic headlines simplify and hype what is usually a complex situation, ignoring key factors which shape electoral outcomes and inflate far-right results, such as trends in abstention and distrust towards mainstream politics. When these parties do not perform as well as predicted, the circus moves on to the next election and the hype starts afresh, often playing a role in the framing of, and potentially influencing, the process and policies, but also ignoring problems in mainstream, establishment parties and the system itself—including racism.

This overwhelming focus on electoral competition tends to create a normative standard for measurement and brings misperceptions about the extent and form of mainstreaming. Tackling the issue of mainstreaming beyond elections and electoral parties and more holistically does not only allow for more comprehensive analysis that addresses diverse factors, manifestations, and implications of far-right ideas and politics, but is much-needed in order to challenge some of the harmful discourses around the topic peddled by politicians, journalists, and academics. To do so, we must first understand and engage with the idea of the ‘mainstream’, a concept that has attracted very little attention to date; its widespread use has not been matched by definitional clarity or subjected to critical unpacking. It often appears simultaneously essentialised and elusive. Crucially then, we must stress two key points establishing its contingency and challenging its essentialised qualities. The first of these points is therefore that the mainstream is constructed, contingent, and fluid. We often hear how the ‘extreme’ is a threat to the ‘mainstream’, but this is not some objective reality with two fixed actors or positions. They are both contingent in themselves and in relation to one another. In any system, the construction and positioning of the mainstream necessitate the construction of an extreme, which is just as contingent and fluid. These are neither ontological nor historically-fixed phenomena and seeing them as such, which is common, is both uncritical and ahistorical. What is mainstream or extreme at one point in time does not have to be, nor remain, so. The second point is that the mainstream is not essentially good, rational, or moderate. While public discourse in liberal democracies tends to imbue the mainstream or ‘centre’ with values of reason and moderation, the reality can be quite different as is clearly demonstrated by the simple fact that what is mainstream one day can be reviled, as well as exceptionalised and externalised, as extreme the next, and vice versa. Racism would be one such example. As such, the mainstream is itself a normative, hegemonic concept that imbues a particular ideological configuration or system with authority to operate as a given or naturalise itself as the best or even only option, essential to govern or regulate society, politics and the economy. One of the main problems with the lack of clarity over the definition of the mainstream is that its contingency is masked through the assumption that it is common sense to know what it signifies, thus contributing to its reification as something with a fixed identity. Most people (including academics) feel they have a clear idea of what is mainstream; they position themselves according to what they feel/think it is and see themselves in relation to it. We argue that a critical approach to the mainstream, which challenges its status as a fixed entity with ontological status and essentialised ‘good’ and ‘normal’ qualities, is crucial for understanding the processes at play in the mainstreaming of the far right. To address various shortcomings, we define the process of mainstreaming as the process by which parties/actors, discourses and/or attitudes move from marginal positions on the political spectrum or public sphere to more central ones, shifting what is deemed to be acceptable or legitimate in political, media and public circles and contexts. The first aspect we draw attention to is the agency of parties and actors in the matter. Far-right actors are often positioned as agents, either unlocking their own success through internal strategies or pushing the mainstream to adopt positions that would otherwise be considered ‘unnatural’ to it. While we do not wish to dismiss the potential power of far-right actors to exert influence, it is essential to reflect on the capacity of the mainstream to shift the goalposts, especially given the heightened status and power that comes from the assumptions described above. What we highlight as particularly important is that shifts can take place independently and that the far right is not the sole actor which matters in understanding the process of mainstreaming. A far-right party can feel pressured or see an opportunity to become more extreme by mainstream parties moving rightward and thus encroaching on its territory. However, a far-right party can also be made more extreme without changing itself, but because the mainstream moves away from its ideas and politics. The issues associated with the assumed immovability and moderation of the mainstream have led towards a lack of engagement with the role of this group. It is therefore imperative to challenge these assumptions and capture the influence of mainstream elite actors, particularly with regard to discourse, in holistic accounts of mainstreaming. This leads on to one of the core tenets of our framework, which places discourse as a central feature with significant influence across other elements. Too often, discourse has been swallowed up within elections, seen solely as the means through which party success might be achieved, but we argue that it can stand alone and that the mainstreaming of far-right ideas is not something only of interest and concern when it is matched by electoral success. Our framework highlights the capacity of parties and actors from the far right or mainstream (though the latter has greatest influence) to enact discursive shifts that bring far-right and mainstream discourse closer or further from one another. Problematically, we argue, discourse is often seen solely in terms of its strategic effects for electoral outcomes. While we do not deny its importance in this regard, we suggest that discursive shifts may not always be connected in the ways we might expect with elections, and that the interpretation of electoral results can itself feed into the process of normalisation. First, changes at the discursive level do not always lead to a similar electoral trajectory, nor do the effects stop at elections: the mainstreaming of far-right ideas and narratives (including in and as policies) has the potential to both weaken the far right’s electoral performance if mainstream politicians compete over their traditional ground or bolster such parties by centring their ideas as the norm. Whatever the case, we must not lose sight of the effects on those groups targeted in such exclusionary discourse. The impact of mainstreaming does not stop at the ballot box. This feeds into the second key point about elections, in that the way they are interpreted can further contribute to normalisation, either through celebrating the perceived defeat of the far right or through hyping the position of far-right parties as democratic contenders. Certainly, this does not mean that we should not interrogate the reasons behind examples of increased electoral success among far-right parties, but that we must do so in a nuanced and critical manner. We must therefore guard against simplistic conclusions drawn from electoral, but also survey, data which we discuss at length in the article. Accounts of the electorate, often referred to through notions of ‘the people’ or ‘public opinion’, have tended to skew understandings of mainstreaming towards bottom-up explanations in which this group is portrayed as a collection of votes made outside the influence of elite actors. Through our framework, we seek to challenge these assumptions and instead underscore the critical role of discourse through mediation in constructing voter knowledge of the political context. Far from being a prescriptive framework or approach, our aim is to ensure that future engagement with the concept, process and implications of mainstreaming is based on a more critical, rounded approach. This does not mean that each aspect of our framework needs to be engaged with in great depth, but they should be considered to ensure criticality and rigour, as well as avoid both the uncritical reification of an essentially good mainstream against the far right, and the normalisation and mainstreaming of the far right and its ideas. We believe it is our responsibility as researchers to avoid the harmful effects of narrower interpretations of political phenomena which present an incomplete yet buzzword-friendly picture (i.e. ‘populist’ or ‘left behind’), often taken up in political and media discourse, and feed into further discursive normalisation. This brings us to the more epistemological, methodological, and political reason for the intervention and framework proposal: the need for a more reflective and critical approach from researchers, particularly where power and political influence are an issue. It is imperative that researchers reflect on their own role in contributing to the discourse around mainstreaming through their interpretations of related phenomena. This is important in the context of political and social sciences where, despite unavoidable assumptions, interests and influence, objectivity, and neutrality are often proclaimed. Necessarily, this demands from researchers an acknowledgement of their own positionality as not only researchers, but also as subjects within well-established and yet often invisibilised racialised, gendered, and classed power structures, notably those within and reproduced by our institutions, disciplines, and fields of study. by Blendi Kajsiu

There is a strong tendency to conflate populism and anti-politics. In the media every political actor or party that rejects the political status quo is labelled populist, regardless of their political ideology. In academia, on the other hand, the rejection of the existing political class and institutions is understood as the very essence of populism. According to one of the leading political theorists of populism, Margaret Canovan, ‘in its current incarnations populism does not express the essence of the political but instead of anti-politics.’[1] In similar fashion, Nadia Urbinati argues that anti-politics constitutes the basic structure of populist ideology.[2] Hence, the concept of populism has been ‘regularly used as a synonym for “anti-establishment”’.[3]

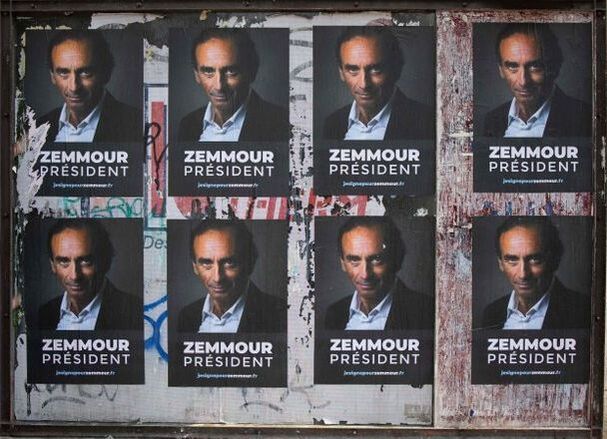

The conflation between populism and anti-politics is understandable given that anti- elitism constitutes one of the core features of populism in its dominant definitions, whether as a thin ideology or as a political logic.[4] In most contemporary populist movements anti- elitism has taken the specific form of anti-politics, whether in the rejection of traditional political parties (la partidocracia) by Alberto Fujimori in Peru, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, or the denunciation of the political establishment by Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece. The traditional political class has also been the main enemy of right-wing neo-populist movements in Latin America.[5] Likewise, dissatisfaction with the political establishment has constituted an important source of right-wing populism in Europe.[6] Hence, the confusion between anti-politics and populism, even when absent theoretically, can easily appear at the empirical level. Yet anti-politics and populism are two distinct phenomena. The rejection of the political status quo, the denunciation of the existing political class and institutions can be articulated from different ideological perspectives. Politics, politicians, and political institutions can be rejected for violating the popular will (populism), for undermining market competition (neoliberalism), for weakening the nation (nationalism), for undermining tradition and family values (conservatism), or for producing deep inequalities and high concentrations of wealth (socialism). Hence, there are populist, conservative, socialist, neoliberal, and liberal anti-political discourses, alongside many others, which combine various ideological perspectives in their rejection of the political class and political institutions. It is only when the rejection of politics, politicians, and the political status quo is combined with key concepts of populism that we can talk of populist anti-politics. Following Mudde, I understand populism as a “thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”[7] The antagonism between the honest people and the corrupt elite, the people as the underdog and the only source of political legitimacy, as well as popular sovereignty, constitute the conceptual core of any populist discourse because they are present in all its historical manifestations. Populism functions as an ideology insofar as it partially fixes the meaning of these concepts in relation to each other. Thus, from a populist perspective, democracy is understood primarily as a direct expression of ‘the’ people’s will rather than as a set of institutional or procedural arrangements (liberal democracy). Popular sovereignty here means that ‘the people are the only source of legitimate authority’. Political legitimacy is defined in terms of the will of the people, as opposed to tradition (conservatism) or procedures (liberalism). Within the people–elite antagonism, the people are defined vertically as the underdog (the plebs) against a corrupt elite. This is different from the horizontal definition ‘the-people-as-nation’ within nationalist ideology, where the people are defined primarily in opposition to non-members rather than against the elite.[8] The last point is important in order to distinguish between populism and nativism. The latter denotes an exclusionary type of nationalism ‘that holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by the members of the native group [….] and that non-native people and ideas are fundamentally threatening to the homogeneous nation-state.’[9] It is normally conflated with populism given that ‘both nationalism and populism revolve around the sovereignty of “the people”, with the same signifier being used to refer to both [“the people” and “the nation”] in many languages (e.g., “das Volk”).’[10] Although in practice these two ideologies are interweaved, they define ‘the people’ in distinctive ways. From a populist perspective, the people is defined vertically as the underdog against an oppressive elite. This is an open-ended definition which implies that all those social groups that are being oppressed by the elite could be part of the people. In other words, the ‘people’ is not defined positively through a fixed set of criteria, as much as negatively in opposition to the corrupt elite. The nativist ideology, on the other hand, defines the people horizontally as a nation in opposition to other nations, cultures, religions, or social groups. This is a closed definition that assigns a set of positive attributes to the people in terms of language, territory, religion, race, culture, or birth. Hence, from a nativist perspective the national elite remains ‘part of the nation even when they betray the interests of the nation and their allegiance to the nation is questioned.’[11] This is not true in the case of populism where ‘the elite’ by definition is not part of the ‘people’. Given that populism as a very thin ideology articulates a very limited number of key concepts, anti-politics can rarely be simply, or even primarily, populist. This is why a number of scholars have argued that although radical right-wing parties in Europe are often labelled populist they are primarily defined by ethnic nationalism or nativism.[12] In other words, their rejection of the existing political class and institutions is more nativist than populist. Yet despite the growing consensus that ethnic nationalism or nativism is the key ingredient of extreme right-wing parties in Europe, they are still labelled populist radical-right parties, and not nationalist or nativist radical-right parties. This is not to say that there cannot be right-wing political parties that articulate anti-politics primarily in a populist fashion, although they are hard to find in Europe. A number of leaders and political movements in Latin America, usually labelled neo-populists, have successfully combined a neoliberal ideology with populism. Presidents Alberto Fujimori in Peru (1990–2000), Carlos Menem in Argentina (1989–1999), and Fernando Collor (1990–1992) in Brazil combined populism and neoliberalism when in office.[13] In all these cases, populism, and not nativism, was the key element of their political articulation. Hence the articulation of populism with nativism in right-wing populist movements is contingent rather than necessary. It appears natural due to the Eurocentrism of most literature on radical right-wing populism, which focuses on Europe and often ignores right-wing populist movements in Latin America and beyond. Our obsession with populism can blind us to the ideological zeitgeist that fuels the current anti-politics. Instead of identifying the populist versus anti-populist cleavage that has supposedly displaced the left–right division, it could be more productive to clarify how ideological polarisation has been producing rejections of current politics, whether along the cosmopolitan–nationalist or the left–right ideological dimensions. Indeed, ideological polarisation along the left–right and the cosmopolitan–nationalist spectrums would tell us a lot more about the 2020 Presidential Elections in the USA than the populist–non-populist cleavage. A focus on nationalism would tell us a lot more about the emergence of radical-right parties in Europe, as well as the rise of extreme right-wing politicians such as Eric Zemmour in France, which mainstream media calls “populist”. Not to mention that populism, unlike nationalism, tells us very little about the current invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Focusing on populism diverts our attention from the multiple ideological dimensions of anti-politics discourses today. The rejection of politics, the political class, and political institutions is rarely developed simply from a populist perspective, especially in Europe. It is often justified in the name of tradition, equality, identity, and especially in the name of the nation. Equating populism with anti-politics tends to obscure the ideological dimension of the latter, especially when populism is understood as a non-ideological phenomenon that lies beyond the left–right spectrum. [1] M. Canovan, The People (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005), 78. [2] N. Urbinati, Me the People: How Populism Transforms Democracy (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2019), 62. [3] J. W. Müller, What Is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 1. [4] See C. Mudde, 'The populist zeitgeist', Government and Opposition 39:4 (2004), 542–563, at p. 543 and E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005). [5] K. Weyland, 'Neopopulism and Neoliberalism in Latin America: Unexpected Affinities', Studies in Comparative International Development 33:3(1996), 3–31, at p. 10. [6] See C. Fieschi & P. Heywood, 'Trust, cynicism and populist anti-politics', Journal of Political Ideologies 9:3 (2004), 289–309; as well as H. G. Betz, ‘Introduction’, In Hans-Georg Betz and Stefan Immerfall (Eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998). [7] C. Mudde, 'The populist zeitgeist', 543. [8] B. De Cleen and Y. Stavrakakis, 'Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism', Javnost – The Public 24:4 (2017), 301–319, at p. 312. [9] C. Mudde, ‘Why nativism not populism should be declared word of the year’, The Guardian, 7 December 2017, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/07/cambridge-dictionary-nativism-populism-word-year [10] B. De Cleen and Y. Stavrakakis, 'Distinctions and Articulations', 301. [11] B. De Cleen, ‘Populism and Nationalism’ in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 342–362, at p. 351. [12] See B. Moffit, ‘The populism/Anti-populism Divide in Western Europe’, Democratic Theory 5 (2018), 1–16; B. De Cleen, ‘Populism and Nationalism’, 349; J. Rydgren, ‘Radical right-wing parties in Europe: What’s populism got to do with it?’, Journal of Language and Politics 16:4 (2017), 485–496. [13] K. Weland, 'Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe', Comparative Politics 31 (1999), 379–401, at p. 379. by Federico Tarragoni

In an old textbook on populism, the psycho-sociologist Alexandre Dorna described the phenomenon as a 'volcanic eruption': a surge of the repressed impulses, instincts and fantasies of the masses onto the political scene.[1] This analysis is very common today, especially in relation to the so-called 'far-right populisms', such as the governments of Trump, Bolsonaro, or Orbán. We will not be talking here about the fantasies (in a Freudian sense) of which populism would be the political vector, but about those that it expresses in the speaker who speaks about it. What exactly are we saying when we categorise something as 'populist'? It is well known that the word is used more to stigmatise than to designate positively. Its proliferation in public debate over the past decade has been unprecedented: in 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary awarded it 'word of the year'. Its inflation in the public debate points to the undeniable re-emergence of the ‘people’ as political operator, especially since the subprime crisis of 2008. On the extreme right, this resurgence is expressed in xenophobic nativist movements that oppose the national people to immigration and to ethnic and sexual minorities. On the far left, it appears in plebeian movements that oppose the ‘people’ as a democratic subject to a ruling class, judged to be in collusion with neoliberal economic elites, and accused of corrupting democracy. Both renewals emerge in the global political space. While the former may be compatible with a neoliberal economic orientation, as in the cases of Trump and Bolsonaro, the latter is in frontal opposition.

The fantasies of populism Contemporary uses of populism, whether they see it as a threat or as a chance to radicalise democracy, assume that both phenomena lie in the same direction; that they are politically and historically univocal. This is the fantasy I am talking about: in the Freudian sense, the main imaginary production by which those who speak of populism today escape from reality. Here, the historical and sociological reality is that the 'people' of the extreme right have very little to do with the 'people' of the far left. Each of us can easily see that their projects, situated on opposite sides of the political spectrum, have more differences than similarities. In spite of this, the majority of studies in political science persist in seeing in these two phenomena some variants of the same reality: populism. This would be anchored in the extremes, which would therefore be strictly comparable in terms of their political use of the ‘people’. With a touch of irony, I call 'populology' the scholarly discourse structured around this thesis, which takes up the old 'horseshoe theory' in French political science.[2] A thesis that seems to describe, in a clear and transparent way, our political actuality in the 21st century. But its simplicity tends to oversimplify it to the point of obscuring its real socio-political dynamics for at least three reasons. The first reason is that the only thing in common between the extreme-right and the far-left 'populists' is nothing other than the opposition between the 'people' and the 'elites'. However, this opposition takes on such different and even opposite meanings in its two ‘variants’ that it is no longer sufficient to qualify something common. The 'people' is an extremely polysemous concept, since classical Greece, where there are about twenty words used to describe it: dèmos or the whole of the citizens, laos or the whole of the individuals sharing a common culture, ethnos or the whole of the members of a clan, genos or the whole of the individuals sharing a common ancestor, hoi polloi (‘the most numerous’) or the social majority of a population, ochlos or the people in tumult, ekklesia or the assembled people, etc. Each of these terms designated this intangible and ineffable entity that was the ‘people’, based on a specific property or operation that it is supposed to perform in the polis. This definitional difficulty has been further complicated by modern political ideologies, all of which have more or less adopted this central word of democratic modernity. This is why the term is now invoked to designate political projects that have more differences than similarities between the extreme right and the radical left. Unless we consider, as the vast majority of contemporary theorists of populism do, that it is an essentially discursive phenomenon. That it is therefore extremely plastic, reflecting the emptiness of the word ‘people’ and the appeals that invoke it. But are the affects and political behaviours that these populist appeals aggregate really comparable? In reality, if populism is discursive by nature, all politics is discursive; in the same way, liberalism would be a political discourse centered on the word 'freedom', which is also fundamentally ambiguous. Would we then be ready to assert that all political actors who have claimed or are claiming today 'freedom' against a regime that deprives them of it, whatever the political project defended, are comparable? Are we ready to compare feminists, socialists, Berlusconi, the Austrian FPÖ, and so many others? We should recognise that almost all the political phenomena of our modernity are 'liberal' in this sense. Just as today we end up thinking that everything is potentially populist, when we talk about the 'people' against the 'elites'. The second reason is that behind this idea that populism refers to any appeal to the ‘people’, we are in fact confusing distinct political phenomena: social movements, such as Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados or the Gilets jaunes, all structured by the opposition ‘people vs. elites’; political organisations, such as the Rassemblement national, Podemos, and the Labour-affiliated group Momentum, all calling for the ‘people’ against the establishment; modes of appealing to the electorate by the ruling class, more or less demagogic, such as those of Silvio Berlusconi, Nigel Farage, or Donald Trump; finally, political regimes based on the principle of the embodiment of the people by the Head of State, such as those of Erdogan, Putin, or Orbán. These phenomena are ontologically heterogeneous. Here the concept of populism is more confusing than elucidating, because it leads to abandon more precise historical concepts, such as demagogy, neo- or post-fascism, Bonapartism, and authoritarianism, in favour of a vague and fuzzy word. In other terms, there is more in common between authoritarian regimes, whatever their modes of legitimation, than between an authoritarian regime claiming to represent the people against corrupt elites, and a social movement claiming to constitute one against the ruling elites. Similarly, if populism describes modes of appealing to the electorate based on proximity, illusion, and overpromising, it would be more correct to speak of demagogy; it would then be necessary to question the reasons for its rise in contemporary political communication, as much among the establishment parties as among the anti-establishment ones. The third reason is that behind the idea that populism is a plastic discursive construction, there is a tendency to confuse positive and value judgements. The ‘people’, like all our political terms, is a controversial normative word: as a synonym for collective sovereignty, it can be seen as the quintessence of democracy, or as a symbol of an oppressive totality, representing a threat to individual freedoms. If we do not empirically observe the concrete practices that this 'people' produces in the social space, we can be led to take our own value-judgments about 'the people' as science. Depending on the different ways of defining democracy (this concept which is also inseparably descriptive and normative), one will thus make a different case for populism.[3] If, like Jan-Werner Müller, we define democracy as a procedural horizon for safeguarding individual liberties, the 'people' inevitably becomes suspect, both in the political discourse of the extreme right and the far left.[4] If, like Chantal Mouffe, we define democracy as an agonistic horizon of conflictuality, the ‘people’ becomes the very quintessence of the democratic dynamic, because it is always constructed by opposing groups claiming democracy against the elites.[5] Thus, on Müller's side, we lose sight of certain emancipatory uses of the ‘people’, which can radicalise a democracy conceived in a strictly procedural way. But on Mouffe's side, we lose sight of the fact that certain conflictual constructions of the ‘people’ are actually anti-democratic, such as those proposed by the neo-Nazi movement FPÖ in Austria or by the ‘Golden Dawn’ in Greece, because they challenge the liberal foundations of our democracies. A new genetic approach In fact, before we can even discuss whether populism is progressive or regressive for our democracies, we need to agree on what we are talking about. We need to clear up the many ambiguities to which contemporary uses of populism give rise: ambiguities in the classification and in the comparison that is proposed. In reality, we still do not know what populism is: not only do we not really know how to explain it, but we continue to disagree, among scholars, on what it encompasses empirically. Despite the huge inflation of books and articles on the subject, we are still at the first steps of a scientific method. This makes the enterprise questionable for those who consciously choose not to use the concept. But it also makes it exciting and thrilling for those who take the problems posed by the concept seriously, seeking new solutions to its enigma. I propose a new 'genetic' approach, which consists in going back to the founding experiences of populism: the Russian narodnichestvo (between 1840 and 1880), the American People's Party (at the end of the 19th century) and the national-popular regimes in Latin America (between 1930 and 1960).[6] Why them and not others? Why this return to the past when populism is such a current phenomenon? For one simple reason: these three historical experiences are defined by the entire scientific community as populist; they do not carry the ambiguities of what is too broadly called populism today. It is therefore a solid starting point for a new analysis. This is all the more true since historical distance makes it possible to look at current events in a more complex way. If there is one lesson of social sciences since Max Weber, it is this: we must analyse the present from the past, and not the opposite. Yet, concerning populism, we often move between presentism (the idea of the radical newness of our present, disjointed from the past) and anachronism (the distorted reading of past populisms from our present). By comparing these founding experiences of populism, we obtain an ideal type: in the sense of Max Weber, a 'logical utopia' resulting from the stylisation of reality and the deliberate accentuation of certain features, which help to understand empirical reality by comparison with the model. The first recurring feature, which will be accentuated, is that populism always appears within the crisis of governments claiming to be legitimated by the people, but excluding them socially, economically, and politically. The second recurring feature is that populism is structured by the opposition between the 'people' and the 'elite', but it gives an ideologically singular interpretation of this opposition, which defies any comparison between the far left and the extreme right. The 'people' appears as the name of a utopia: a democracy restored to its sovereign subject, involved in a dynamic of radicalisation of both freedom and equality. Populist democracy is conceived against the reduction of democracy to representative governments: an ‘elective aristocracy’ that is always potentially oligarchic.[7] The 'elite' is the force that opposes this project of founding a populist democracy. The 'people' and the 'elite' thus do not define two concrete social groups, but two forces of democratic modernity: the 'people' is associated with the insides, with life and tradition; the 'elite' with the outsides, with reason and modernisation. This idea is central to the writings of the founder of populist ideology, the Russian Alexander Herzen (1812–70), who provided a systematic version of it at about the same time as Marx and Engels were working on the idea of communism. The Russian populists (narodniki), who were to deeply influence Lenin (his brother had been one of them), were convinced that the peasantry, the social majority of the people, could provide the organisational forms on which the future democracy could be built. As a radical political ideology, populism is accompanied by the expression of a certain revolutionary charisma. This is the third recurrent feature of the phenomenon. In the Russian and American cases, this charisma is ‘available’ to the actors of the social movement, who can all aspire to embody the mobilisation: it is an ‘acephalous’ charisma. When the American farmers created their own party, the People's Party, this charisma was gradually personalised: the party acquired two brilliant charismatic leaders, James B. Weaver and William Jennings Bryan. The latter, a great critic of the financial system of the Gold Standard, deemed responsible for the American social crisis, gave a speech in 1896 with eschatological connotations: the ‘Cross of Gold’ Speech. This young lawyer from Nebraska attacked the idle holders of capital in the ‘great American cities’, accusing them of strangling the working classes and draining the country's ‘broad and fertile prairies’. ‘The humblest citizen in all the land’, he said, ‘when clad in the armor of a righteous cause, is stronger than all the whole hosts of error that they can bring. I come to speak to you in defense of a cause as holy as the cause of liberty, the cause of humanity’. ‘You come to us’, he replied to the supporters of the Gold Standard, ‘and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the Gold Standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country’. ‘If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the Gold Standard as a Good thing’, he concluded, ‘we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a Gold Standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold’. In the Latin American case, populism had powerful charismatic leaders too: Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina, Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico, Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in Colombia, Rómulo Betancourt in Venezuela, Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre in Peru, Víctor Paz Estenssoro in Bolivia, Carlos Ibáñez del Campo in Chile. Finally, a last recurring feature of populism is the socially heterogeneous nature of the mobilisations. They involve alliances between impoverished working classes and middle classes made precarious by the economic crisis: they all share the view that the ruling class is disconnected from the needs of the population's majority. Moreover, these mobilisations have no real class basis: they bring together different democratic causes carried by ‘subaltern groups’ in the sense of Antonio Gramsci, whose relations of domination go from class, to gender, to race.[8] Populism is therefore an ideology of crisis. It appears in a context of socio-economic crisis which becomes a legitimacy crisis of a government which, claiming to rule in the name of the people, appears collectively as the expression of an oligarchy's interests. Because of this context, populism operates as a crisis phenomenon. Thus, we can speak of 'populist moments' because populism can hardly survive beyond the crisis that institutes it. Despite its mobilising potential, because of the revolutionary charisma it brings to the stage and its capacity to federate several social demands, it is not sustainable. Why is this so? The Latin American case provides some answers to this tricky problem. From the outset, it is difficult to achieve a programme as ambitious and vague as founding a radical democracy. On the one hand, such a programme should cover all spheres of social life, from culture to education, employment, citizenship. Let's think of Perón's Partido Justicialista, founded in 1946 and charged with democratising Argentinian society in the areas of education, university, civic and social rights, work and social inequalities, gender, culture ... A project that can lead to many disappointments among the mobilised popular base once populism is in power. The radical wing of Peronism—the Montoneros—and the communist left constantly deplore public policies that do not meet the democratic expectations of the Argentinian people. On the other hand, such a maximalist project runs the risk of removing all obstacles to State intervention in society: an intervention which, adorned with the noble objective of radicalising democracy, may end up subjecting to it the preservation of certain freedoms, such as those of the press or the unions. In short, as much as populism is useful and necessary as a protest ideology, it is not very effective as an ideology in power. This is all the more the case because, by giving a central place to charisma, it leads, in the conditions of the organised competition for power, to a strong personalism. The mobilisation's leader who becomes the charismatic Head of State tends to introduce into populism a strongly vertical dimension, which is opposed to the horizontality of the social movement. The opposition between the 'people' and the 'elite' also tends to change once it is transformed into an ideology of public action: from a radically democratic opposition (deepening democracy by injecting more popular sovereignty), it tends to polarise society between 'friends' of the people and 'friends' of the elite. During my fieldwork in Venezuela (2007-11), one of the countries of the populist revival in the twenty-first century, I was confronted daily with the harmful effects of such polarisation, which ultimately undermines democratic communication.[9] In institutional politics as well as in ordinary life, people had stopped debating, and instead fought each other in the name of imaginary plots attributed to one part of society against the other. This logic, combined with personalism and statism, finally legitimated an authoritarian turn within the State that began in 2005 and was reinforced with Nicolas Maduro's election. What is left of populism? As the Latin American case shows, this is the main problem with populism in power: an ideology that aims to re-found or radicalise democracy quickly comes into conflict with the logic of the State. This reflection is useful when considering what to do with populism today. What remains of this historical ideology? What is left is clearly left-wing populism. From an ideological point of view, the so-called 'right-wing populism' refers to a completely different historical matrix: that of ethnic nationalism (or nativism), with strong antisemitic connotations, which was born in Europe at the end of the 19th century, irrigated the fascist movements, and was rebuilt in the 1980s against the migratory globalisation and the emancipatory struggles of the 1970s. Left-wing populism, by contrast, emerged in Europe and the United States after the Latin American ‘left turn’ in a similar context to that of past populisms: a socio-economic crisis, the subprime crisis, which revealed the disconnection of neoliberal elites from the social needs of the majority. The democratic socialism of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Labour Momentum, Podemos, the Five Star Movement, Syriza, La France insoumise: they have canalised the new populist mobilisations. For those of them that have come to power, the same structural problems of Latin American populisms can be observed, even if the danger of an out-of-control statism is less pronounced there, due to the smaller role of military elites in the socio-historical construction of States. Like past populisms, populisms of our time are very ephemeral: none of them are in the same place as they were three years ago. The concessions made to the establishment have almost erased some of them from the electoral map, like Syriza. All of them have strong internal cleavages. One is the opposition between a ‘pragmatist’ wing and a ‘radical’ wing, as in the Italian Five Star Movement during Mario Draghi's government. The other is the split between 'populist strategy' and 'leftist strategy', as in Podemos (between Íñigo Errejón and Pablo Iglesias) and La France insomise (between Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Clémentine Autain). In short, populism still appears as a singular political moment; a moment that already seems, in part, to be behind us. If the populist moment of 2008 has closed, with the disappointments that populist parties in power have generated in their falling electorates, another one may arise in the future. Two points should then be borne in mind. Firstly, populism does not remain the same between the destituting, contesting phase and the reinstituting phase in power; it changes politically. It is therefore necessary to control this mutation. Secondly, it is becoming urgent to separate the destiny of the extreme right and that of the radical left: the idea that there would be a populist dynamic common to both prevents us from thinking about the necessary renewal of a left-wing populism. On the contrary, this idea causes systematic haemorrhaging of left-wing voters who see in a supposedly common strategy with the extreme right a legitimate reason for disgust. Thinking about a left-wing populism for the years to come can only be done on the basis of these two analytical and strategic observations. [1] Alexandre Dorna, Le populisme (Paris : PUF, 1999). [2] Federico Tarragoni, L’esprit démocratique du populisme. Une nouvelle analyse sociologique (Paris : La Découverte, 2019). On the 'horseshoe theory', see Jean-Pierre Faye, Le siècle des idéologies (Paris : Press Pocket, 2002). For a critical point of view, cf. Annie Collovald and Brigitte Gaïti (eds), La démocratie aux extrêmes. Sur la radicalisation politique (Paris : La Dispute, 2006). [3] Quentin Skinner, ‘The Empirical Theorists of Democracy and Their Critics’, Political Theory, 1, Issue 3 (1973), pp. 287-306; John Dunn, Setting the People Free. The Story of Democracy (New York: Atlantic books, 2005). [4] Jan-Werner Müller, What is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). [5] Chantal Mouffe, For a Left Populism (London: Verso, 2018). [6] Federico Tarragoni, « Populism, an ideology without history? A new genetic approach », Journal of Political Ideologies, 26, Issue 3 (2021). DOI : 10.1080/13569317.2021.1979130. [7] Bernard Manin, The Principles of Representative Government (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). [8] Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks [25 §4, 1934] (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011). [9] Federico Tarragoni, L’Énigme révolutionnaire (Paris : Les Prairies ordinaires, 2015). 6/12/2021 There is always someone more populist than you: Insights and reflections on a new method for measuring populism with supervised machine learningRead Now by Jessica Di Cocco