by Eileen M. Hunt

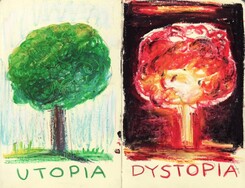

Mary Shelley is most famous for writing the original monster story of the modern horror genre, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). She was also the author of the pandemic novel that unleashed the dominant tropes of post-apocalyptic literature upon modern political science fiction. Her fourth completed novel, The Last Man (1826), pictured the near annihilation of the human species by an unprecedented and highly pathogenic plague that surfaces during a war between Greece and Turkey in the year 2092. Shelley’s dystopian worlds, in turn, have inspired Marxist social and political theorists in their Promethean critiques of capitalism. Both Frankenstein’s monster and Shelley’s monster pandemic resonate with us during the time of Covid-19 because of the power and prescience of her iconic critiques of human-made disasters.

While she lived in Italy with her husband Percy, Shelley helped him translate and transcribe Plato’s Symposium, which contains the etymological origin of the English word “pandemic” (in ancient Greek, πάνδημος).[1] In Plato’s philosophical dialogue on the meaning of love, the goddess “Pandemos” is the “earthly Aphrodite” who oversees the bodily loves of “all” (pan) “people” (demos), men and women alike.[2] In the aftermath of the 1642-51 English Civil Wars and the 1665–66 Great Plague of London, the adjective “pandemic” gained salience in both political and medical contexts in seventeenth-century English. It could refer to either the disorders of democratic government by all people (as in monarchist John Rogers’s 1659 condemnation of the “unjust Equality of Pandemick Government”), or the visitation of pestilence to undermine the stability of the entire body politic (as in doctor Gideon Harvey’s 1666 description of “Endemick or Pandemick” diseases that “haunt a Country”).[3] According to this conceptual genealogy sketched by literary theorist Justin Clemens, two important homophonic variants of “Pandemick” emerged in the aftermath of the English Civil Wars. Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) defined “Panique Terror” as a contagious “passion” of fear that happens to “none but in a throng, or a multitude of people.”[4] Then John Milton invented the word “pandaemonium” for his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) to depict Satan’s hell as a kingdom where all the little devils lived in sin-infected chaos.[5] Indebted to her deep reading of Plato, Hobbes, and Milton, Shelley’s The Last Man conceived the global plague as an “epidemic” that affects or touches upon (epi) all (pan) people (demos) precisely because it stems from the disruptions of collective human corruption, panic, and politics.[6] In her first novel, Shelley had metaphorically rendered the revenge of Frankenstein’s “monster” upon his uncaring scientist-maker as an unstoppable “curse,” “scourge,” and “pest” upon their family and potentially “the whole human race.”[7] This unnamed “creature” was nothing less than a “catastrophe,” brought to life by the chemist Victor Frankenstein from an artificial assemblage of the dead parts of human and nonhuman animals.[8] His dark motivation for using his knowledge of chemistry, anatomy, and electricity to bring the dead back to life was the sudden loss of his mother to scarlet fever while she cared for his sick sister, cousin, and bride-to-be, Elizabeth. In her second great work of “political science fiction,” Shelley found new horror in reversing the direction of the metaphor.[9] No longer was the monster a plague: the plague itself was the monster. Shelley not only wrote the origin story for modern sf with Frankenstein. She also laid down the ur-text for modern post-apocalyptic fiction in The Last Man. With her great pandemic novel, Shelley panned out to see all plagues as human-made monstrosities that leave “a scene of havoc and death” behind them.[10] What made plagues so ghastly was their exponential power to multiply—causing a concatenation of disasters for their human authors, other afflicted people, and their wider environments on “a scale of fearful magnitude.”[11] In The Last Man, Shelley conceived all plagues—real and metaphorical—as human contaminations of wider environments. Bad human behaviors corroded the people closest to them, then spread like toxins through the cultural atmosphere to destroy the health and happiness of others. The ancient plagues of erotic and familial conflict, war, poverty, and pestilence had reproduced together and persisted into modernity through centuries of modelling, imitation, and replication of humanity’s worst behaviors in culture, society, and politics. Midway through The Last Man, the Greek princess Evadne issues an apocalyptic prophecy: humanity would soon be incinerated in a vortex of war, passion, and betrayal.[12] As she dies of “crimson fever” on a pestilential battlefield, she curses her beloved and the leader of the Greek forces Lord Raymond for abandoning her for his wife Perdita. “Fire, war, and plague,” she cries, “unite for thy destruction!”[13] As if on cue, the seasonal “visitation” of “PLAGUE” in Constantinople escalates into an international pandemic. With her uncanny insight into the social genesis of epidemics and other plagues upon humanity, Shelley—through the voice of Evadne—anticipated the economic and political theory of pandemics that has gained currency in the twenty-first-century. Back in 2005, the Marxist historian Mike Davis warned the world that zoonotic viral pandemics like the avian flu and SARS-CoV—whose genetically mutated strains enabled them to leap from nonhuman animals to a mass of human victims—were The Monster at Our Door.[14] While Davis did not cite Shelley in his book, he didn’t need to: the allusion to Frankenstein was perfectly clear in the title. Davis was writing in a long tradition of reading the monster imagery of Frankenstein through the technological lenses of Marxism. Based in London for much of his career, Marx himself was likely influenced by the massive cultural impact of Shelley’s Frankenstein and her husband Percy’s radical political poetry, as they filtered through the nineteenth-century British socialist tradition.[15] Despite his stubborn dislike of Marxist hermeneutics and other social scientific readings of literature, the critic Harold Bloom was always the first to admit that “it is hardly possible to stand left of (Percy) Shelley.”[16] Given his revolutionary-era philosophical debts to Rousseau, Wollstonecraft, and Godwin, it is not surprising that Percy Shelley felt outraged by the news of the August 1819 “massacre at Manchester.”[17] The British calvary charged an assembly of 60,000 workers, killing some and injuring hundreds more. While living in exile in Italy with his pregnant wife, in deep mourning over the recent losses of their toddler William to malaria and infant Clara to dysentery, Percy composed a timeless lyric to summon the poor to non-violent protest. Not published until 1832 due to the poet's untimely death in 1822 and the poem's controversial argument, “The Mask of Anarchy” became an anthem for the peaceful liberation of people from the slavery of poverty and political oppression: "Rise like Lions after slumber In unvanquishable number-- Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you-- Ye are many—they are few."[18] Completed two years before Percy’s rousing defense of popular uprising against the power of the imperial state, Frankenstein made a parallel political point. Literary scholar Elsie B. Michie underscored that the tragic predicament of Frankenstein’s abandoned Creature fit what Marx would call, in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, the plight of “alienated labor.”[19] Modern capitalistic society cruelly severed the poor from the material sources and products of their own making. Frankenstein likewise left his Creature bereft of any benefits of the “bodies,” “work,” and “labours” by which “the being” had been shaped into “a thing” such as “even Dante could not have conceived.”[20] When read against the background of Shelley’s novel, Marx’s theory of alienated labor recalls the dynamic of confrontation and separation that drives the conflicted yet magnetic relationship of the Creature with his technological maker. Taken out of the context of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, some of Marx’s words could easily be mistaken for a commentary on Frankenstein, as in: “the object that labour produces, its product, confronts it as an alien being, as a power independent of the producer.”[21] While capitalism produced the workers from its elite economic control of the tools of science, technology, and economics, the workers received no benefit from those same tools that a truly benevolent maker might have otherwise bestowed upon them. What could such a creature do but confront their maker with a demand for the goods necessary for the development of their humanity? In his 1857-58 “Fragment on Machines” from the Grundrisse, Marx rather poetically captured the process of human alienation from the products of their own technological labors: "Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified."[22] Reworking the twin Greek myths of Prometheus, in which the titan molds humanity from clay and then forges the mortals’ rebellion from the gods through the gift of fire, Marx follows Shelley in depicting human beings as self-replicating machines: for they are artificial products of their own willful mind to dominate and transform nature through technology. As the political philosopher Marshall Berman argued in All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (1983), Marx’s bourgeoisie is a Promethean “sorcerer” akin to “Goethe’s Faust” and “Shelley’s Frankenstein,” for it created new and unruly forms of artificial life that in turn raised “the spectre of communism” for modern Europe.[23] What Mike Davis has done so brilliantly, in the spirit of both Marx and the Shelleys, is to use this nineteenth-century techno-political imaginary to conceptualise humanity’s responsibility for the self-destructive course of pandemics in our time. Generations of readers of Frankenstein have felt compelled to pity the Creature, despite his train of crimes, and come to view him as a product of the fevered madness of his father-scientist. In this rhetorically persuasive Shelleyan tradition, Davis pushes his readers to see Covid-19 and other pandemics as products of the myopic mindsets of the human beings who selfishly let them loose upon the world. With the rise of the novel coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, Davis stoically set up his home office in his garage. As most countries around the globe went under lockdown during the endless winter of 2020, he sat down to update his book The Monster at Our Door for the second time.[24] Like Shelley and many writers of political science fiction after her, from Octavia Butler to Margaret Atwood to Emily St. John Mandel, the historian had predicted that a new, deadly, and devastating severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) would visit the planet in the twenty-first century.[25] Reports from the World Health Organisation had sparked Davis’s concerns about the latest iteration of the avian flu, or H5N1 influenza.[26] H5N1 had fast and lethal outbreaks in 1997 and 2003—while exhibiting a terrifying 60% mortality rate.[27] It passed from chickens to humans in Hong Kong in 1997, and, on a much more alarming scale, through “commercial poultry farms” in South Korea, China, Thailand, Vietnam, and other regions of Southeast Asia in 2003, via a “highly pathogenic” and “novel strain,” H5N2.[28] Like the epidemiologists, ecologists, and anthropologists whose work he studied, the historian feared that the “Bird flu” could erupt into a pandemic that might kill more than the deadliest virus of the twentieth century.[29] Davis recounted that an estimated “40 to 100 million people”—including his “mother’s little brother”—had been taken by the H1N1 avian influenza of 1918.[30] The newspapers at the time described the pandemic as the “Spanish Flu,” even though it started in the United States and elsewhere.[31] Because Spain remained neutral during the First World War, its press went uncensored. Spanish newspapers took the lead in reporting cases of the rising international wave of influenza. Far from war-torn continental Europe, the first recorded human outbreak of this flu mutation—which swiftly flew from birds to people—in fact began in a rural farming community and military base in Kansas.[32] A dreadful re-run of 1918 loomed in our near future, Davis insisted, if nations did not prepare for the worst. Governments needed to reduce “the virulence of poverty,” improve health care, and stockpile medical and protective equipment.[33] They had to regulate international trade, factory farming, and flight travel with an eye toward protecting public health from a resurgence of uncontrolled zoonotic viral respiratory infections. And they must support the best virology and vaccine research before the next epidemic snowballed into a global economic and political disaster. Under lockdown last April, Davis changed the title of his updated book to The Monster Enters, to mark a shift in his historical perspective. Just a few weeks earlier, disease ecologist Peter Daszak announced in a New York Times op-ed that we had officially entered the “age of pandemics.”[34] The monster pandemic of our political nightmares was no longer the threat of the avian flu at our door. It had already entered our world as SARS-CoV-2—a novel coronavirus thought to have been initially transmitted from bats to humans near Wuhan, China—and it was leaving a mounting set of economic, social, and political disasters in its wake. More of these novel and volatile contagions stood on the horizon like shadows of Frankenstein’s creature cast over the Earth. “As the hour of the pandemic clock ominously approaches midnight,” Davis had reflected on the last page of The Monster at Our Door, “I recall those 1950s sci-fi thrillers of my childhood in which an alien menace or atomic monster threatened humanity.”[35] Without vaccines to stop their circulation across nations, these viral mutations threatened to destroy their human creators like Frankenstein’s creature had done. Ironically, they could upend the globalised economic and political systems that had proliferated their diseases through international trade, travel, and economic inequality. Never purely natural phenomena, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and the latest strain of the avian flu were in fact the products and “plagues of capitalism.”[36] In the chapter titled “Plague and Profit,” Davis made explicit his debt to both Marx and Shelley. He gave the name “Frankenstein GenZ” to the virulent “H5N1 superstrain—genotype Z.”[37] At the turn of the twenty-first century, poultry factories in China unwittingly bioengineered this deadlier strain of H5N1, in the aftermath of the 1997 outbreak in Hong Kong. By inoculating ducks with an “inactivated virus” and breeding them for slaughter in their processing plants, they created a new and potentially levelling form of the avian flu, H5N2.[38] Almost two centuries before our current historical seer Mike Davis, Mary Shelley saw the monster pandemic coming for us in the future. The concluding volume in my trilogy on Shelley and political philosophy for Penn Press--The Specter of Pandemic—is about why she and some of her followers in the tradition of political science fiction have been able to predict with uncanny accuracy the political and economic problems that have beset humanity in the “Plague Year” of two thousand and twenty to twenty-one.[39] For Shelley, the reasons were deeply personal. She experienced an epidemic of tragedies on a depth and scale that most people could not bear. During the five years she lived in Italy from 1818 to 1823, the young author, wife, and mother saw the infectious diseases of dysentery, malaria, and typhus fell three children she bore or cared for, before her husband Percy drowned, at age twenty-nine, in a sailing accident off the coast of Tuscany. Her emotional and intellectual resilience in the face of the many plagues upon her family is what made her a visionary sf novelist, existential writer, and political philosopher of pandemic. [1] Justin Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus; or, Pandemic, Panic, Pandaemonium,” Crisis & Critique 7:3 (2020), 41-60; Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert, eds., The Journals of Mary Shelley (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, [1987] 1995), 220. [2] Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus,” 47-48. [3] Ibid., 43, 45. [4] Ibid., 50. [5] Ibid., 52. [6] Shelley, The Last Man, 183. In March 1820, Shelley noted Percy’s reading Hobbes’s Leviathan, sometimes, it seems, “aloud” to her. See Shelley, Journals, 311-313, 345. The epigraph for Frankenstein is drawn from Book X of Milton’s Paradise Lost: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay/To mould me man? Did I solicit thee/From darkness to promote me?” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism, ed. J. Paul Hunter, second edition (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 2. [7] Shelley, Frankenstein, 69, 102, 119. [8] Ibid., 35. [9] Eileen Hunt Botting, Artificial Life After Frankenstein (Philadelphia: Penn Press, 2020), introduction. [10] Mary Shelley, The Last Man, in The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley, ed. Jane Blumberg with Nora Crook (London: Pickering & Chatto, [1996] 2001), vol. 4, 176. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid., 139. [13] Ibid., 144. [14] Mike Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu, and the Plagues of Capitalism (New York: OR, 2020). [15] Chris Baldick, In Frankenstein’s Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 132, 137. [16] Harold Bloom, Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The Power of the Reader’s Mind over a Universe of Death (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 183. [17] “Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘The Mask of Anarchy (1819),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/PShelley/anarchy.html. [18]Ibid. [19] “Elsie B. Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Articles/michie1.html. [20] Shelley, Frankenstein, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36. [21] “Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990).’” [22] Karl Marx, “The Fragment on Machines,” The Grundrisse (1857-58), 690-712, at 706. Accessed 28 November 2020 at https://thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf [23] Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983), 101. [24] Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu (New York: New Press, 2005); Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu. Revised and Expanded edition (New York: Macmillan, 2006). [25] Eileen Hunt Botting, "Predicting the Patriarchal Politics of Pandemics from Mary Shelley to COVID-19," Front. Sociol. 6:624909. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.624909 [26] Davis, The Monster Enters, 87-100. [27] Natalie Porter, Viral Economies: Bird Flu Experiments in Vietnam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 2. [28] Porter, Viral Economies, 1-2.; Davis, The Monster Enters, 120-23. [29] Ibid. [30] Davis, “Preface: The Monster Enters,” in The Monster at Our Door, 44-47. [31] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin, 2004), 171. [32] Ibid., 91. “1918 Pandemic Influenza Historic Timeline | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC,” April 18, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/pandemic-timeline-1918.htm. [33] Davis, The Monster Enters, 53. [34] Peter Daszak, “Opinion | We Knew Disease X Was Coming. It’s Here Now.,” The New York Times, February 27, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/opinion/coronavirus-pandemics.html. Davis cites Daszak’s article with David Morens and Jeffery Taubenberger, “Escaping Pandora’s Box: Another Novel Coronavirus,” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (2 April 2020) in his introduction to The Monster Enters, 3, 181. [35] Davis, The Monster Enters, 180. [36] See the subtitle of Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu and the Plagues of Capitalism. [37] Davis, The Monster Enters, 119, 122 [38] Ibid. [39] Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations Or Memorials of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as Well Publick as Private, Which Happened in London During the Last Great Visitation in 1665 (London: E. Nutt, 1722). by David Benbow

The concept of ideology seems to have been supplanted in contemporary critical theory by the concept of discourse.[1] Postmodernist scholars, such as Michel Foucault[2] and Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari,[3] have criticised the concept of ideology. Nonetheless, the two concepts are potentially compatible.[4] I believe that the concept of ideology is superior to the concept of discourse because, as David Hawkes noted, it mediates between the ideal and the material.[5] The work of the Frankfurt School philosopher, Theodor Adorno, and his conceptualisations of ideology, are particularly useful in examining the relationship between the ideal and the material in modern neoliberal societies.[6] The contemporary relevance of Adorno’s work is evident in the burgeoning literature concerning the philosopher—see, for example, Blackwell’s A Companion to Adorno, published in 2020, which contains the largest collection of essays by Adorno scholars in a single volume.[7] I have utilised Adorno’s conceptualisations of ideology, within my own work, to examine different aspects of the law relating to health and healthcare.

Adorno’s distinction between liberal ideology and positivist ideology,[8] and his conceptualisations of reification, informed my analysis of reforms which have marketised and privatised the English National Health Service (NHS).[9] I also made use of Adorno’s method of ideology critique to demonstrate how many public statements regarding the high-profile Charlie Gard[10] and Alfie Evans[11] cases (which involved disputes between parents and clinicians regarding the treatment of young infants), for example by United States (US) politicians (such as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz), were unjustifiably critical of socialised medicine.[12] The cases led to renewed proposals for the best interests test,[13] which is currently determinative in such cases, to be replaced with a significant harm test. I employed Adorno’s notion of the dialectic of enlightenment (the idea that reason can engender unreason[14]) to undermine the argument that parents would make better decisions in these types of cases.[15] I contended that the clinicians in such cases reflexively acknowledged the limits of medicine, in contrast to the parents, who appear to have suffered from false hope.[16] Adorno’s ideas are also informing my current research projects on vaccine confidence (and the influence of anti-vaccination ideology) and the potential of human rights to address health injustices in states within the Global South. In respect of the former, I have employed the psycho-social dialectic methodology that Adorno developed in his research into anti-Semitism[17] to identify the objective social factors which have influenced the increase in vaccine hesitancy.[18] In respect of the latter, Adorno noted that rights may be tacitly critical of existing conditions[19] and thus I am developing a paper regarding how they may be used to articulate present injustices within the Global South (and elsewhere) with a view to their remedy. In the chapter on the topic of the concept of ideology, published as part of the Frankfurt School’s book Aspects of Sociology, Adorno distinguished between liberal ideology and positivist ideology.[20] In Adorno’s view, positivist ideology, which he thought was becoming more prominent in modern societies, hardly says more than ‘things are the way they are’.[21] By contrast, the emphatic concepts of liberal ideology, such as freedom, equality and rights, are often used, within discourse, to justify certain states of affairs (or changes to them).[22] Such emphatic concepts can also be used to critique existing conditions. There are different modalities of the related concept of reification in Adorno’s work. One modality of reification in Adorno’s work is philosophical reification, which refers to phenomena being treated as fixed.[23] An example of philosophical reification is the exchange principle, which treats unlike things alike.[24] Another modality of reification in Adorno’s work is social reification, which refers to means becoming ends in themselves.[25] Both of these modes are evident in consumerism. Reification may lead to estrangement, whereby people become strangers or enemies to one another.[26] Estrangement is the opposite of solidarity, which Rahel Jaeggi defines as ‘standing up for each other because one recognises one’s own fate in the fate of the other’.[27] Reification may undermine the solidarity which has been pivotal in the creation and continuation of the NHS. I have analysed the emphatic concepts of freedom and equality and how they have been used within the discourse of successive governments regarding the English NHS. I have also considered the potential reifying effects of the market reforms that successive governments have implemented within the English NHS. When the NHS was established, in 1948, it was to be publicly answerable via ministerial accountability to Parliament. However, this was deemed to be a constitutional fiction.[28] Since the 1970s, there have been efforts to enhance patient and public involvement within the NHS via two types of mechanisms, identified by Albert Hirschman: voice and choice.[29] In the neoliberal era, the preference has been for choice mechanisms (although attenuated voice mechanisms have persisted). This preference is evident in the use of indicators and market mechanisms to facilitate competition among NHS providers. The internal market introduced by the Conservatives, in the 1990s,[30] was justified on the basis of enhancing patient choice,[31] although evidence indicates that it reduced the choices available to patients.[32] The mimic-market established in the English NHS by the New Labour governments, in the 2000s, afforded private healthcare companies increasing opportunities to deliver NHS services and gradually extended patient choice to any willing provider.[33] New Labour sought to naturalise the relationship between patients and the NHS as a consumerist one.[34] However, studies indicate that many patients were recalcitrant in this regard[35] and often did not utilise the opportunity to exercise choice when it was available to them.[36] The latest English NHS market was introduced by the Health and Social Care (HSC) Act 2012. This statute places duties on commissioners to act with a view to enabling patients to make choices.[37] Such commissioners are also required to comply with regulations passed pursuant to S.75 of the statute,[38] and, prior to Brexit, with European Union (EU) public procurement law,[39] in tendering services. Such laws have coaxed many commissioners into tendering services in circumstances where they did not think that it was best for patients, [40] which is symptomatic of social reification, as the market has become an end in itself. New methods for enabling patients to compare providers, such as friend and family test (FFT) scores, have also been introduced. These are symptomatic of philosophical reification, as the process of reducing quality (patient experiences) into quantity (a number) is one of abstraction,[41] which is unlikely to capture the complexity of patient experiences. In any event, patient choice, which was used to justify the coalition’s reforms, has taken a backseat,[42] and the market created by the HSC Act 2012 has primarily involved providers competing for tenders. The intention of many of the policymakers who designed the market reforms to the English NHS thus seems to have been to get private providers into the NHS, rather than to extend patient choice. I contend that voice mechanisms are a preferable method of empowering patients by allowing them to convey the complexity of their experiences and to influence clinical practices. Adorno was critical of the concept of equality, on the basis that it could obscure important differences.[43] Nonetheless, equality of access to the NHS (based on need) and the reduction of health inequalities are principles which, I contend, are compatible with an Adornian perspective. The Welsh Marxist theorist, Raymond Williams, helpfully distinguished between dominant, residual, and emergent norms within his work. [44] I have conceptualised neoliberal norms (such as competition and choice) as dominant norms, the founding principles of the NHS (such as equality of access, comprehensiveness, and universality) as residual norms (as they are remnants from the era of the social democratic consensus, which preceded the neoliberal era) and the reduction of health inequalities as an emergent norm.[45] In the neoliberal era, different UK governments have all articulated their support for the residual norm of equality of access. However, this has been undermined, for example, by the ability of foundation trusts to earn 49% of their income from private patients.[46] The other residual norms, such as comprehensiveness, have also been undermined by successive governments, within the neoliberal era, thereby extending the exchange principle (as patients are now required to pay for some health services). The issue of health inequalities was not a priority of the Conservative governments between 1979 and 1997, which sought to bury the Black Report[47] and which rebranded such inequalities, in a positivistic manner, as health variations.[48] In contrast, both the New Labour governments between 1997 and 2010 and the Conservative-led governments since 2010 have adopted the goal of reducing health inequalities. The HSC Act 2012 created statutory duties for different actors to have regard to the need to reduce such inequalities.[49] However, the impact of the main economic policy (austerity) pursued by governments since 2010, has increased such inequalities.[50] Austerity negatively affected NHS capacity and resources, as well as population health, rendering the NHS less resilient to the current Covid-19 pandemic.[51] The reduction of health inequalities requires alternative economic policies to austerity. Ultimately, I have identified both liberal and positivistic elements in the discourse of successive governments, in the neoliberal era, in relation to the English NHS. Consequently, government discourse pertaining to the English NHS has not become completely positivistic. Rather, there are liberal elements which provide members of the public and scholars with a basis for critique. The statements of successive governments that they were desirous of empowering patients, respecting the NHS’ founding principles and reducing health inequalities can be used to critique their policies (which have not empowered patients, have undermined the NHS’ founding principles and are likely to exacerbate health inequalities) and to conceive alternative policies. The development of sustainability and transformation plans (STPs), integrated care systems (ICSs) and integrated care providers (ICPs), and the increased emphasis on integration in the discourse of the government and NHS England (a non-departmental body which oversees the day-to-day operation of the NHS in England and commissions primary care and specialist services) has been interpreted by many as a move away from the competition that has dominated the English NHS in the neoliberal era.[52] A recent Kings Fund report found that there has been a move away from procurement to collaboration within the English NHS (with the former being used as a method of last resort).[53] However, some fear that the new structures being established within the English NHS may undermine its founding principles and afford new opportunities for private companies.[54] I have argued elsewhere that the policies of successive governments pertaining to the English NHS were indicative of market fetishism.[55] The recent award of many contracts to private companies under special powers that circumvent normal tendering rules, during the Covid-19 pandemic,[56] suggests a fetishism for private companies and not necessarily with competitive processes. I have identified the corporate influence on the reforms to the English NHS of successive governments.[57] Such corporate influence has ostensibly also affected the current government’s response to the pandemic.[58] Although I have identified several potential reifying effects of government reforms to the NHS, which could undermine the solidarity which led to its creation and continuation, the adherence of the public to unprecedented rules, such as national lockdowns, during the Covid-19 pandemic, to ‘Protect the NHS’ (as government slogans state), is a palpable contemporary manifestation of such solidarity. The pandemic has also exposed the impact of persistent health inequalities.[59] If efforts to undermine the founding principles of the NHS continue, the slogan ‘Protect the NHS’ will persist as a powerful means of providing an immanent critique of government policies. Additionally, growing awareness of health inequalities may lead to increased clamour for more action than government promises and statutory duties. [1] Rahel Jaeggi, ‘Rethinking Ideology’, in Boudewijn de Bruin and Christopher F. Zurn (eds.), New Waves in Political Philosophy (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 63. [2] Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977 (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1980), 118. [3] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Continuum, 1987), 76. [4] Trevor Purvis and Alan Hunt, ‘Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology...’, The British Journal of Sociology, 44(3) (1993), 498. [5] David Hawkes, Ideology: 2nd Edition (London: Routledge, 2003), 156. [6] See, for example, Charles A. Prusik, Adorno and Neoliberalism: The Critique of Exchange Society (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020); Deborah Cook, Adorno, Foucault and the Critique of the West (London: Verso, 2018). [7] Peter E. Gordon, Espen Hammer, and Max Pensky (eds.), A Companion to Adorno (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2020). [8] See Theodor Adorno, ‘Ideology’, in Frankfurt Institute of Social Research (ed.), Aspects of Sociology, (London: Heinemann, 1973), 202. [9] David Benbow, ‘An Adornian Ideology Critique of Neo-liberal Reforms to the English NHS’, Journal of Political Ideologies 26(1) (2021), 59–80. [10] Great Ormond Street Hospital v Constance Yates, Chris Gard and Charles Gard (A Child by his Guardian Ad Litem) [2017] EWHC 972 (Fam) [20]. [11] Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust v Mr Thomas Evans, Ms Kate James, Alfie Evans (A Child by his Guardian CAFCASS Legal) [2018] EWHC 308 (Fam) [6]. [12] David Benbow, ‘An Analysis of Charlie’s Law and Alfie’s Law’, Medical Law Review 28(2) (2020), 227. [13] Children Act 1989, S.1(1). [14] See Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), xvi. [15] Benbow, ‘An Analysis’, 237–8. [16] Ibid. [17] Theodor Adorno, The Psychological Technique of Martin Luther Thomas' Radio Addresses (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010). [18] The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared this to be a global health threat in 2019. See WHO, ‘Ten threats to global health in 2019’, available at https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed 29 October 2020). [19] Adorno and Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 141. [20] Adorno, ‘Ideology’, 202. [21] Ibid. [22] Deborah Cook, ‘Adorno, Ideology and Ideology Critique’, Philosophy & Social Criticism 27(1) (2001), 10. [23] Anita Chari, A Political Economy of the Senses: Neoliberalism, Reification, Critique (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2015), 144. [24] David Held, Introduction to Critical Theory: Horkheimer to Habermas (Cambridge: Polity, 2004), 220. [25] Chari, Political Economy of the Senses, 144. [26] John Torrance, Estrangement, Alienation and Exploitation: A Sociological Approach to Historical Materialism (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1977), 315. [27] Rahel Jaeggi, ‘Solidarity and Indifference’, in Ruud ter Meulen et al (eds.), Solidarity and Health Care in Europe (London: Kluwer, 2001), 291. [28] Alec Merrison, Report of the Royal Commission on the National Health Service, Cmnd 7615. (London: HMSO, 1979), 298. [29] Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organisations and States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970). [30] Via the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990. [31] Department of Health, Working for Patients (London: Stationery Office, 1989), 3–6. [32] Marianna Fotaki, ‘The Impact of Market-Oriented Reforms on Choice and Information: A Case Study of Cataract Surgery in Outer London and Stockholm’, Social Science & Medicine 48(100 (1999), 1430. [33] Department of Health (DOH), Principles and Rules for Co-operation and Competition (London: DOH, 2007), 10. [34] For example, the word consumer appeared more in Labour’s health policy documents than in its policy documents for other policy areas. See Catherine Needham, The Reform of Public Services under New Labour: Narratives of Consumerism (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), 115. [35] John Clarke, Janet Newman, and Louise Westmarland, ‘Creating Citizen-Consumers? Public Service Reform and (Un)willing Selves’ in Sabine Maasen and Barbara Sutter (eds.), On Willing Selves: Neoliberal Politics vis-à-vis the Neuroscientific Challenge (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), 136. [36] Anna Dixon, Patient Choice: How Patient’s Choose and How Providers Respond (London: Kings Fund, 2010), 20. [37] NHS Act (2006), S.13I and S.14V as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25. [38] National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations (No.2) (S.75 Regulations), SI 2013/500. [39] Directive 2014(24) EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on Public Procurement and repealing directive 2004/18/EC, OJ L. 94, 28 March 2014. This was implemented in the UK via the Public Contracts Regulations, SI 2015/102. Such regulations are still in force. [40] D. West, ‘CCGs open services to competition out of fear of rules’, Health Services Journal, 4 April 2014. [41] Theodor Adorno, Lectures on Negative Dialectics: Fragments of a Lecture Course 1965–1966 (Cambridge: Polity, 2008), 127. [42] Chris Ham et al., The NHS under the Coalition government part one: NHS Reform (London: Kings Fund, 2015), 18. [43] Theodor Adorno, Negative Dialectics (New York: Continuum, 1973), 309. [44] Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 122. [45] David Benbow, ‘The sociology of health and the NHS’, The Sociological Review 65(2) (2017), 416. [46] NHS Act (2006), S.43(2A) as amended by Health and Social Care (HSC) Act (2012), S.164(1). [47] Department of Health and Social Service (DHSS), Inequalities in Health: Report of a Research Working Group (London: DHSS, 1980). [48] Clare Bambra, Health Divides (Bristol: Policy Press, 2016), 185. [49] For example, the Secretary of State for Health is required to have regard to the need to reduce health inequalities in exercising their functions (NHS Act (2006), S.1C as amended by the HSC Act (2012), S.4.) and NHS England and CCGs are required to have regard to the need to reduce inequalities in respect of access (NHS Act (2006), S.13G(A) and S.14T(A) as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25) and outcomes (NHS Act (2006), S.13G(B) and S.14T(B) as amended by HSC Act (2012), S.23 and S.25). [50] Clare Bambra, ‘Conclusion: Health in Hard Times’ in Clare Bambra (ed.), Health in Hard Times: Austerity and Health Inequalities (Bristol: Policy Press, 2019), 244. [51] Chris Thomas, Resilient Health and Care: Learning the Lessons of Covid-19 in the English NHS (London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2020), 3. [52] Hugh Alderwick et al., Sustainability and Transformation Plans in the NHS: How are they being developed in practice? (London: Kings Fund, 2016), 7. [53] Ruth Robertson and Leo Ewbank, Thinking Differently about Commissioning (London: Kings Fund, 2020). [54] Allyson M. Pollock and Peter Roderick, ‘Why we should be concerned about Accountable Care Organisations in England’s NHS’. British Medical Journal 360 (2018). [55] Benbow, ‘The sociology of health and the NHS’, 420. [56] British Medical Association (BMA), The role of private outsourcing in the Covid-19 response (London: BMA, 2020), 4. [57] Benbow, ‘An Adornian Ideology Critique’, 66, 68. [58] Peter Geoghegan, ‘Cronyism and Clientelism’, London Review of Books 42 (2020). [59] Abi Rimmer, ‘Covid-19: Tackling health inequalities is more urgent than ever, says new alliance’. British Medical Journal 371 (2020). |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed