|

17/4/2023 (Re)inventing the nation on the centenary of the Turkish Republic: A Rhetorical Political Analysis of Erdogan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’Read Now by Arife Köse

History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogeneous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now [Jetztzeit].

- Walter Benjamin - On 28 October 1923, dining with his friends, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is said to have declared ‘Gentlemen! We are going to announce the Republic tomorrow.’ The next day, he proclaimed the following law: ‘The form of government of the Turkish state is the republic.’[1] Once the law passed by the Turkish Parliament later the same day, the State of Türkiye as republic, which is now a century old, came into being. From one perspective, that date—29 October 1923—is just a place on the calendar, ‘chronos’, or quantitative time. However, as Benjamin argued, calendars are also ‘monuments of historical consciousness,’[2] marking out moments of what rhetoricians call ‘kairos’—measuring not quantity of time but a quality of timely action. Kairos points to the ‘interpretation of historical events’ because it is about the significance and meaning assigned to them.[3] It is also about the opportunity to be grasped now for action that cannot be grasped under different conditions or situations. Thus, kairos always has an argumentative character since the significance given to historical events are always contested and temporarily decontested in specific ways. In this respect, due to the significance and meaning assigned to it, the foundation of the Turkish Republic can be understood as a moment when ‘chronos is turned into kairos’.[4] Now, 100 years since its foundation, the country’s incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is seeking to create a moment of kairos again, using it to reinvent the idea of ‘Turkishness’ itself and to turn it into a time of action in the service of continuity of his rule. This is a rhetorical act that requires ideological analysis. In this article, I examine how Erdoğan fulfils such a rhetorical act through Rhetorical Political Analysis (RPA) of the speech he delivered on 28 October 2022. This speech was intended to set forth his vision for the future of the country on the day that the Turkish Republic entered its centenary and was entitled a ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. I will begin by providing some historical and theoretical background, followed by a rhetorical analysis of his political thinking around the centenary. My argument is not only that his ideological thinking shapes his actions but also his understanding of Turkishness in the context of the centenary is shaped by his strategic action, aiming at winning the elections in Türkiye in 2023 and consolidating his and his party’s leadership position in the future. Background As 29 October 2023 marks the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Erdoğan, as both President of Türkiye and leader of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), delivered a speech on 28 October 2022 to set out the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. The gathering was held in the capital Ankara, in Ankara Sports Hall which accommodates 4,500 people. 11 political parties were invited to the event. The only party that was not invited was the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), the Kurdish-led, left-wing party which has been denounced by Erdoğan as a ‘terrorist’ entity due to its alleged connection with PKK, the Kurdish paramilitary organisation. Alongside the political parties, AKP Members of Parliament, mayors, party members, and supporters were invited to the event—as well as some artists, NGOs, academics, and journalists (unusually including notable dissident journalists). The event, at which Erdoğan spoke for 1 hour 40 minutes, lasted 2 hours overall.[5] Like the morphological approach to ideological analysis pioneered by Michael Freeden,[6] rhetorical approaches to ideologies start from the position that political ideologies are ubiquitous, and a necessary part of political life. However, unlike morphological analysis, they focus on ideological arguments rather than ideological concepts, on the grounds that ideologies are ‘shaped by and respond to external events and externally generated contestation from alternative ideologies’.[7] Accordingly, Alan Finlayson suggests using RPA to analyse ideologies, in order to pay attention not only to the semantic and structural configuration of ideologies but also to political action, such as the strategies that political actors develop to intervene in specific situations. Further, RPA focuses on the performative aspect of political ideologies by drawing attention to how performativity becomes part of the morphology of the ideology in-question through foregrounding specific political concepts.[8] Alongside the concepts provided by the rhetorical tradition, RPA also draws on kinds of proof classically categorised as ethos, pathos and logos.[9] Whereas ethos indicates appeal to the character of the speaker with whom the audience is invited to identify, pathos is about appeal to the emotions. Lastly, logos indicates appeal to reason by political actors in their attempt to have the audience reach particular conclusions by following certain implicit or explicit premises in their discourse. Overall, RPA commits to the analysis of politics ‘as it appears in the wild’.[10] The rhetorical situation Analysis of political speeches begins with the analysis of the rhetorical situation, since every political speech is created and situated in a particular context. In this respect, every political speech, alongside its verbal manifestation, performs an act by intervening in a particular situation.[11] Those situations are characterised by both possibilities and restrictions for the orator, and it is one of the primary characteristics of skilled orators to know how to employ the opportunities and overcome the restrictions embedded in the situation. In such situations, political ideologies are not only deployed by political actors to intervene in and shape the situation, but they are also shaped through the act of intervention when addressing the challenges or trying to persuade others of a particular action. In the case of Erdoğan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ there are two exigencies: first, for him, it is a moment of kairos to be grasped and put in the service of his strategic aim of winning the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023. For this, evidently, he needs to prove to the people beyond his supporters that he is the leader of the whole country who can carry it into the future. Thus, it is an opportunity for him to amplify his rule as President of Türkiye, which is a position that he gained as a result of regime change in Türkiye 2017. On 16th April 2017, Turkish voters approved by a narrow margin constitutional amendments which would transform the country into a presidential system. This was followed by the re-election of Erdoğan as the President of the country on 24 June 2018 with the support of MHP (Nationalist Movement Party). Since then, AKP and MHP work together under the alliance called People’s Alliance. The new system has been widely criticised on the grounds that it weakens the parliament and other institutions and undermines the separation of powers through politicisation of the judiciary and concentration of executive power in a single person. Overall, this has led to an increasingly authoritarian governance.[12] The second exigency for Erdoğan is the enduring economic crisis from which the country has been suffering since June 2018. In that year, as a result of Erdoğan’s insistence on lowering interest rates, Türkiye experienced an economic shock, resulting in a dramatic loss in the value of Turkish Lira against Dollar. Since then, three Turkish Central Bank governors have been successively dismissed by Erdoğan. For example, in March 2021, Erdoğan fired then governor Naci Ağbal after he hiked the interest rates against Erdoğan’s persistence on not increasing them no matter what. Erdoğan replaced him with Şahap Kavcıoğlu, known for his loyalty to Erdoğan. Such a move made the economic situation in Türkiye even worse. One of the economic commentators in the Financial Times wrote, ‘Erdoğan’s move leaves little doubt that all the power in Türkiye rests with him, and this will result in rate cuts. This will simply make Türkiye’s inflation problem even worse.’[13] The overall consequence of this turmoil has been rising prices as the Lira collapsed and wages remained stagnant, causing a dramatic drop in people’s purchasing power. By August 2022, according to research, 69.3 percent of the Turkish population were struggling to pay for food.[14] In November 2022, after Erdoğan delivered the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’, the inflation rate reached 85.5%.[15] Erdoğan had to address these two exigencies while he was under heavy criticism not only from international actors and his national opponents but also from the rank and file of his own party about Türkiye’s economy and democracy. His leadership has also been weakening for some time. Erdoğan’s loss in the two big municipalities—Ankara and Istanbul—in the local elections in 2019 exposed the myth that he is a leader who never loses an election. This was the context in which the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ event was held. It was a kairological moment for Erdoğan, where he attempted to reinvent Turkishness and decontest its meaning through an ideological speech-act manifested through various rhetorical moves to position him and his party as the only option in the upcoming elections. The arrangement of the speech Political speeches are significant for the analysis of ideologies not only because of what political leaders say but also because they provide us with the opportunity to observe how the political leader in-question, the nation, and the audience are positioned both in the speech and on the stage. Therefore, paying attention to the arrangement of the speech is as important as the text of the speech. ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ begins with a performance including video clips with narrations, dance performances, songs, and poems. The decoration of the hall can also be thought of as part of this performance. This part of the event can be considered as what is called the ‘prologue’ of the speech in the rhetorical tradition and is also part of ideological analysis. The second part of the event consists of Erdoğan’s speech, where he begins by saluting people in the hall and then praising the Republic and those who fought in the War of Salvation for five minutes. He talks for 35 minutes about the significance of the AKP in the context of the centenary by explaining what it has achieved so far. Following this, he drones on about his party’s achievements by marshalling the services provided by the AKP under his leadership, which lasts for about 20 minutes. After that, he talks about his promises for the ‘Century for Türkiye’ for 20 minutes. In the closing section of the speech, he asks everyone in the hall to stand up and take a nationalist oath with him by repeating his words: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be great! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ In sum, the whole speech consists of two main parts of which the first is about glorifying the Turkish nation and the second part is primarily concerned with the AKP and Erdoğan himself. The speech is therefore arranged in a way which conflates the nation with AKP and Erdoğan and argues for an indispensable bond between them. History without contingency The event begins with a narration by a male presenter accompanied by sentimental music, speaking about the ‘limitless’ and ‘mystical’ universe that operates with self-evident ‘balance’ and ‘order’. We are told that all we do is ‘to find our place within this universe’, and ‘whatever we do, do it right’. Then, around 25 people representing different age groups, genders, and occupations stage a dance performance, embodying the Turkish nation: comprised of a variety of people yet performing the same movements harmoniously under the same flag. In this part, first and foremost, the Turkish nation is situated in its place in time and history. We only hear a narration without seeing the actual person speaking and this narration is accompanied by a video show. The voice asks us to commence history with ‘the moment that the horizon was first looked at’; with the moment that ‘the humanity became humanity’. Within this transcendental history whose origin is undeterminable, the beginning of the Turkish nation is also rendered ambiguous. We are told: If you are asked when this journey began, your response should be ready: When the love of the homeland began! Thus, the origin of Turkish nation is situated into a self-evident kairos without chronos as if its existence is free from the contingent flow of events throughout history. This arrest of contingency is further amplified through the topos of a ‘nation who always does the right thing’: You had forty paths, and maybe forty horses too. If you had not chosen the right thing, you would not have been able to arrive at your homeland, today, now. You chose the right thing even if it was the hard one. Moreover, according to the narration, Turkish nation is a nation which acts now through considering the future; thus, its now is always oriented to the future: You have always envisaged tomorrow. Your history has been written with your choices. Hence, the future also means you. Here we see a nation that always knows what it is doing, always does the right thing and has the power to shape history through the choices it makes. Its actions are always determined by its vision for the future and its future is not contingent but is destiny; a ‘journey’ with its own telos. Then, the narrator asks, ‘when does the future begin?’ and adds, ‘this is the biggest question. The most important question is where the future begins.’ But, this time, we are not left in ambiguity. We are told that it begins ‘here,’ ‘today,’ ‘now’. Strikingly, today is only meaningful as a point of beginning of the future. Hence, our present is also arrested by both our past and our future. We do not have the right to choose our own kairos—our right time for action for a future that is designated by us—but are destined to conform to the already designated kairos for us within, again, already designated chronos: our possibility to have alternative ‘now’ and alternative ‘future’ is taken from us. The ethos of Turkishness Such an articulation of transcendental Turkishness with time and history is amplified with the further delineation of the ethos of the nation. Accordingly, for Erdoğan, the Turkish nation consists of ‘siblings’ who are united under and through the same ‘crescent’—the crescent on the Turkish flag. This is a nation who has the courage and strength to challenge the entire world. Connoting the lyrics of Turkish National Anthem, the lyrics of one of the songs that performed in the event reads: Who shall put me in chains Who shall put me in my place. Then the song continues by saying: There is no difference between us under the crescent We are not scared of coal-black night We are not scared of villains Nevertheless, nowhere in the speech are we told who those ‘villains’, or people who want to ‘put us in chains’ are. Although they cannot stop us from our way, we are expected to consider their existence when we act. Here, we see the manifestation of the ethos of Turkishness through its association with the concepts of freedom, understood as sovereignty, and the Turkish flag. Türkiye is presented as a nation where differences between its members perish under the uniting power of the Turkish flag, and when acting, it always prioritises the protection of its sovereignty. Furthermore, it is argued, the most definitive characteristic of the Turkish nation is that it never stops; it is always in motion, walking towards the future. Thus, the current Turkish Republic constitutes just a small part of its ‘thousand years of life’ so far. However, the Republic is important because it proves what the Turkish nation is capable of: it can achieve the unachievable, and it can overcome the toughest obstacles. But Turkish nation’s ambitions cannot be limited to the current Republic, and no matter how much it suffers now it must keep moving towards the future. In his speech, Erdoğan also uses the metaphor of a bridge, which can be thought together with this topos of ‘nation in motion’. He says, ‘We will raise the Turkish Century by strengthening the bridge we have built from the past to the future with humanistic and moral pillars’. Here, the ‘bridge’ signifies the uninterrupted continuity between past and future built by Erdoğan and his party, where the present is only characterised as a transition point in the ‘journey’ of the Turkish nation towards the future. The performative construction of Turkishness is also accompanied by its articulation with its state, flag and homeland which are the core concepts of Erdoğan’s nationalism that he summaries with the motto ‘one nation, one flag, one state, one homeland.’ For example, in the middle of the hall, there is a huge sundial hanging from the roof, and there is a huge star and crescent on the floor under it that represent the Turkish flag and the homeland. Furthermore, there are 16 balls hanging around the sundial, representing the 16 states founded by Turks throughout history. In Erdoğan’s political thinking, ‘one nation’ signifies indivisible community where the nation is characterised by its ethnic and religious origins- namely being a Turkish and Sunni Muslim. ‘One flag’, on the other hand, signifies the Turkish flag, consisting of red representing the blood of martyrs killed in the Turkish War of Independence, and the white crescent and the star representing the independence and the sovereignty of the country. While ‘one homeland’ represents the land of Türkiye, ‘one state’ signifies the powerful and united Turkish state. The role of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) So far, we have been told who we are, where we are coming from and where we are going, and now, the stage is Erdoğan’s. Erdoğan’s speech consists of three points: situating his party and himself within the history of the Republic by explaining what they have done so far, emphasising his role in this process, then, explaining his promises for the next ‘Century for Türkiye’. For Erdoğan, the AKP is the guarantee of continuity between the past and the future. Accordingly, after beginning his speech by praising Atatürk and the people who fought in the War of Independence, he continues by saying: Of course, there were good things initiated in the first 80 years of our Republic, some of which have been brought to a conclusion. However, the gap between the level of democracy and development that our country should have attained and where we were was so great. Then AKP came into power, his story goes on, and ‘made Türkiye bigger, stronger and richer’ despite all the ‘coup attempts’ and ‘traps’. It was the AKP who actualised ‘the most critical democratic and developmental leap with common sense, common will and common consciousness going beyond all types of political or social classifications’ by including everyone who has been oppressed and discriminated in Türkiye, from Kurds to Jews. Hence, we are told, it is the AKP who will build the Century for Türkiye through the ‘bridge that it establishes from the past to the future’. The ethos of Erdoğan Erdoğan also positions himself as the leader who has brought Türkiye up to date and, thus, the person who can take it into the future. Erdoğan claims that today he is there as a ‘brother’, ‘politician’, and ‘administrator’, as someone who has devoted all his life to the service of his country and the nation. He emphasises that he is there with the confidence that stems from his ‘experience’ in running the country. He then situates himself within other significant or founding leaders in Turkish history by saying, I am here, in front of you with the claim of representing a trust stretching out from Sultan Alparslan to Osman Bey, from Mehmet the Conqueror to Sultan Selim the Stern, from Abdulhamid Han to Gazi Mustafa Kemal. Thus, he is not only one of the leaders in the 100 years of the Turkish Republic but is part of a line of leaders beginning with Sultan Alparslan who led the entrance of Turks to Anatolia with the Battle of Malazgirt in 1071. Moreover, for him, We are at such a critical conjuncture that, with the steps that we take, we are either going to take our place in the forefront of this league or we are going to be faced with the risk of falling back again. This is the task awaiting the leader, one that is so crucial and important that it cannot be undertaken by just any leader. It requires, first and foremost, experience. As proof of his and his party’s level of experience and ability to undertake big and important tasks, he reels off a lengthy list of services provided by the AKP under his leadership in the last 20 years. He gives detailed figures from education, health, transportation, sport etc., such as how AKP has increased the number of classrooms from 343,000 to 612,000, or the number of airports in the country from 26 to 57, or the gross domestic product from 40 billion Lira to 407 billion Lira. Thus, he seeks to close the debate around his way of governance and leadership by depoliticising the discussion through relying on inarguable statistics. Then, he again draws attention to the experience when at the same time emphasising the inexperience of the opposition in running the country and warns, ‘if we do not continue our way by putting one work on top of another one, it is inevitable that we are going to vanish’. Consequently, as happened during the process that led to the independence of Türkiye and the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago, we are put in a position of choosing between two options, this time presented by Erdoğan: either we are going to do the right thing, or we are going to disappear. Concepts of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ Then, Erdoğan moves onto explaining the ‘spirit’, ‘philosophy’, and ‘essence’ of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ that he suggests as a vision for future not only to Türkiye but to the entire world and humanity. He summaries the Vision with 16 core concepts—namely, sustainability, tranquility, development, values, power, success, peace, science, the ones who are right, efficiency, stability, compassion, communication, digital, production, and future. At the core of those 16 concepts lies the claim and promise to make Türkiye a great regional and global power. Such an assertion consists of two dimensions: first, liberal economic developmentalism, which has a prominent place in the Turkish neoliberal conservative political tradition and is structured around the adjacent concepts such as growth, progress, investment, and enhancing competitive power. For example, Erdoğan says, We will make Türkiye one of the largest global industrial and trade centres by supporting the right production areas based on advanced technology, with high added value, wide markets, and increasing employment. According to Erdoğan, the second dimension of making Türkiye great consists of security and stability. For him, Türkiye has become a global and regional power under his rule thanks to the stability and security guaranteed by the presidential system that came into force in 2017. The continuation of this power, he argues, depends on the maintenance of this security and stability, which is also the guarantee for a continuously prosperous economy and the provision of more work and service to the country. When doing this, for him, we are also responsible for the protection of the values belonging to the whole of humanity—not only the Turkish nation—thus we will also ensure ‘cultural and social harmony’. When considered together with the whole speech, this section conforms with Erdoğan’s understanding of Turkishness articulated with himself and his party. According to the reasoning that we are asked to follow throughout the event, instead of being occupied with the present infrastructural problems of the country that have led to the deterioration of the economy and democracy, our thinking and actions must always be future-oriented. In this respect, for example, what matters is not the present economic situation but the economy in the future as presented in the Vision. We might be starving and struggling to continue our daily lives yet still we should continue growing, competing with our rivals, and building bridges and airports. And such a shining future cannot be arrived through change and but only through security and stability ensured by the leadership of the ‘right man’. Then, he makes a call to ‘everybody’ to contribute to the ‘Century for Türkiye’, to ‘discuss’ it, to ‘put forward proposals’, and to ‘create’ and ‘build’ the vision for a Century of Türkiye together. However, it is not clear how people are to contribute to the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ when our past, present, and path to the future are turned into a destiny where we are not agents but prisoners. In fact, such a tension between the closure and opening of the political space can be witnessed throughout the whole speech. For example, Erdoğan says, Today we have come together for the promise of strengthening the first-class citizenship of the 85 million, except the ones committing hate crimes, crimes of terror and crimes of violence. Here, he draws his antagonistic boundaries around who is included and excluded from the nation. When doing this, he uses tellingly vague terms such as ‘crimes of terror’, which can potentially include anyone depending on how far the definition of ‘terror’ becomes stretched. However, despite this, he promises ‘to put aside all the discussions and divisions that have polarised our country for years and damaged the climate of conversation that is the product of our people's unity, solidarity and brotherhood’. This should be understood as part of his effort to secure his existence in the future of the country as the leader of the whole nation, yet still seeking to do this by persuading people of his way of doing politics. Here, the art does not lie in the total closure and opening of the political space but in the ability to convince people that he is the leader who can do both any time he sees convenient—this is a crucial dimension of Erdoğan’s leadership style. Finally, he ends the speech with an oath as he usually does. He asks around 5,000 people in the hall stand up and repeat his words after him: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be big! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ This is his signature; thus, the speech has been signed. Conclusion Erdoğan’s nationalist political thinking in the context of the centenary of the Turkish Republic is shaped by his particular way of intervening in the political situation and has become part of his strategic action. Erdoğan employs the centenary to assert the continuity of his and his party’s leadership by establishing an analogical continuity between the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago and his leadership today. He turns the kairological moment in the past into his kairological moment for himself. He does this by articulating Turkishness, time and history in a way that enables him to situate himself and his party as the only figure that can guarantee such continuity on which the existence of Turkish nation depends—otherwise, we are going to ‘vanish’. Returning to Benjaminian analysis, Erdoğan takes a ‘tiger’s leap into the past’[16] to establish such continuity, however, as history has also shown us, there is a limit for every jump. [1] I quoted this phrase from the amended version of the Turkish Constitution in 1923 known as Teskilat-i Esasiye Kanunu. The Constitution can be reached from: TESKILATI_ESASIYE.pdf (tbmm.gov.tr), p. 373. [2] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, pp. 264. Jonathan Cape. [3] Smith, J. E. (2002). ‘Time and Qualitative Time’, in Sipiora, P. and Baumlin, J. S. (eds.), p. 47, Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in History, Theory and Praxis, pp. 46-57. State University of New York Press. [4] Ewing, B. (2021). ‘Conceptual history, contingency and the ideological politics of time’, in Journal of Political Ideologies, 26:3, p.271. [5] Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan "Türkiye Yüzyılı" vizyonunu açıkladı - YouTube [6] Freeden, M. (1996). Ideologies and Political Theory. Clarendon Press. [7] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.757. [8] Finlayson, A. (2021). ‘Performing Political Ideologies’, in Rai, S. (ed.) et al, The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance, pp. 471-484. Oxford University Press. [9] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, pp. 751-767. [10] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.751. [11] Martin, J. (2015). Situating Speech: A Rhetorical Approach to Political Strategy. Political Studies, 63:1, pp. 25-42. [12] Adar, S. and Seufert, G. (2021). Turkey’s Presidential System after Two and a Half Years. Stiftung Wissenchaft und Politik (SWP) Research Paper 2. [13] Erdogan ousts Turkey central bank governor days after rate hike | Financial Times [14] 70 percent of Turkey struggling to pay for food, survey finds | Ahval (ahvalnews.com) [15] Turkey's inflation hits 24-year high of 85.5% after rate cuts | Reuters [16] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, p.263. Jonathan Cape. by Sergei Akopov

In this essay I will discuss the philosophical, political, and cultural insights that we may gain through a continued debate on an existential approach to political ideology, and on ‘loneliness’ as one of its key concepts. In my previous research, I have attempted to open a wider discussion and show the connection between the ideology of sovereigntism and different forms of what I call “vertically” and “horizontally” organised loneliness. The ‘vertical’ management of loneliness anxiety is usually carried out through an enactment of statism and strong vertical power. By contrast, its ‘horizontal’ equivalent is more associated with non-state lateral transnational networking. There are also risks of a disbalance between the development of ‘vertical’ politics if loneliness arises at the expense of ‘horizontal’ politics, including risks for human freedom[1].

There are three specific themes that I kept in my mind while writing this article. However, before I turn to that, it might be useful to say about where the theme of loneliness came from in the first place. I started to work on this theme in 2018 before COVID-19 made social alienation and loneliness even more popular topic of study. I was originally inspired by my observations of key social characteristics of people who voted in favour of Russian sovereigntism. Sociologically speaking, many of those people had district features and experiences of political alienation and atomisation. For example, social opinion polls signalled that Russia’s 2018 elections and 2020 constitutional amendments referendum were heavily dependent on the mobilisation of elderly voters (77% of those who voted ‘yes’ were above 55 years old)[2]. At the same time, there is data that reveals higher levels of loneliness among Russian pensioners and senior citizens[3]. Was it a pure coincidence that ‘lonely citizens’ voted in favour of further Russia’s ‘geopolitical loneliness’? As I worked through the article in 2019 and 2020 I saw how the theme of loneliness ‘underwent a bit of a renaissance ’ within the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Readers might consequently think that after the pandemic is over, the motivational force of a ‘politics of loneliness’ might lose its relevance. Instead, I am convinced that the pandemic has only ensured that manipulations of human loneliness anxiety are here to stay for the foreseeable future. Moreover, they will remain one of the core topics of human and consequently social life. Therefore, we should not underestimate the role of existential aspects of political processes, including the so-called ‘emotional turn’ in political science. Emotions like loneliness and anxieties about the ontological security of humans and states will not disappear. They will continue to shape ontological insecurities in our societies in even more sophisticated and complex ways. Further into our ‘digital era’, the human drive to get rid of loneliness will remain as vital as it has been since Plato and Laozi, but perhaps in different historical ways. Theorising loneliness politically Returning to the first potential step in my research program, we should build a firm theoretical framework whereby loneliness would be theorised within the web of other, what Felix Berenskoetter called supporting, cognate, and contrasting political concepts’[4]. My synthetic novelty lies in theorising loneliness as a new concept in existential IR and political theory will, for example, require drawing deeper connections between loneliness and its opposites. While some say today that the opposite of negative loneliness can be a creative solitude, others instead consider that to be ‘intimacy’[5]. We need to systematically explore political loneliness as a foundational concept and an umbrella term for empirical phenomena usually described as ‘social isolation’, ‘atomisation’, ‘marginalisation’, ‘silencing’, ‘uprootedness’, ‘commodification’, ‘silencing’, ‘оbjectification’ (or ‘subjectivation’ in terms of Michel Foucault), and so on. We also need to systematise already existing research on loneliness and its links to ‘supporting’ concepts like ‘identity’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘state’, ‘ontological security’, ‘subalternity’ (loneliness in a postcolonial perspective), ‘political power’, and ‘ideology’. I see three blocks of such theoretical analysis. The first corpus of literature I label as ‘psychological’, since loneliness is a political emotion, which requires taking into consideration the apparatus currently applied in political psychology. Here pioneers of psychological research on loneliness include, for example, Clark Moustakas, Ronald Laing, Ben Mijuskovic, Michael Bader, Jacqueline Olds and Richard Schwartz. The second ‘cluster’ of authors is focused more on the sociological and political dimensions of loneliness, which include works on ideology by Gregory Zilborg, Hannah Arendt, Erich Fromm, Zygmunt Bauman, but also the governmentality and biopolitics of Foucault and Agamben. Here I would also put literature on ontological security studies in modern international relations, as well as contemporary research on the existential turn in IR[6]. I would also include in this ‘political’ group case studies on particular geopolitical loneliness in different countries, like ‘taking back control’ during Brexit, ‘making America great again’ in the US under Trump, and so on.[7] The third block of ‘loneliness literature’ comes from philosophical and cultural studies, particularly its phenomenological and existential traditions. Before Foucault, the problem of human liberation from subjectification and commodification was considered by a number of thinkers. Søren Kierkegaard and Paul Tillich, for example, looked at the religious dimension, which should never be disregarded when talking about loneliness anxiety as an existential reservoir for political ideology. Russian philosopher Nikolay Berdyaev explored four modes of loneliness in relation to human conformism and non-conformism. Jean Baudrillard addressed the issue of loneliness as a result of a replacement of reality with the so-called ‘simulacrum’. This idea was developed by Cynthia Weber in her notion of ‘state simulacrum’, by which she understood performative practices of imitation of state sovereignty through politically charged talks on sovereignty and intervention[8]. That raises the problem of what ‘reality’ is, who is ‘the authentic subject’ in more general terms[9], and in Heideggerian and Sartrean terms ‘how can the individual live authentically in a society steeped in inauthenticity’[10]. I find these three blocks of literature vital since they should enable us to outline connections between loneliness anxiety and concepts such as ‘shame’, ‘trauma’, ‘ontological insecurity’, ‘collective identity’, ‘sovereigntism’, and ‘political exceptionalism’ (the latter as a consequence/condition of ‘geopolitical loneliness’). The political manipulation of loneliness As for critical scholars, our second step of research into organised forms of political loneliness should include, in my view, the deconstruction of the existing political manipulations of loneliness. With further ‘digitalisation’ of human life, including its ideological aspects through sophisticated technologies of surveillance, internet trolling, etc., human loneliness and self-objectification may only become more and more camouflaged under the guise of ‘digital efficiency and happiness’. Therefore, a cross-comparative study of ‘trickeries’ with human loneliness are required to uncover the mechanisms that underpin ideological legitimisations of power in different cultural contexts. In my research, I have mostly focused on links between ‘vertical’ national politics of loneliness and ideology within Russian sovereigntism, comparing it, very briefly, with Brexit in the UK. I proposed three discursive models of vertically organised loneliness--historical, psychological, and religious—for the sake of illustrating the theoretical argument, not to claim that such models are either final or all-encompassing. However, links between loneliness and ideology can only be fully considered in the dialectics of (1) a comparative domestic perspective and (2) the implications they have for ‘foreign policy’ in countries that try to justify their geopolitical loneliness in world politics. I mostly concentrated on the ‘undertones’ of Russia’s loneliness in its domestic ideological configurations. However, sooner or later, the domestic politics of loneliness may turn into ‘geopolitical loneliness’ in foreign affairs. In 2018, Vladislav Surkov, one of the former main ideologists of the Kremlin, repeated the slogan of Tsar Alexander III: ‘Russia has only two allies: its army and navy’ – ‘the best-worded description of the geopolitical loneliness which should have long been accepted as our fate’.[11] Beyond the politics of loneliness Two areas that should be developed further are (1) how we can further develop non-vertical, lateral ‘transnational politics of loneliness’; and also (2) how we can demasculinise this ‘vertical politics of loneliness’. The first problem of the underdevelopment of horizontal ties of overcoming loneliness is aggravated by the resurgence of nation states and national borders against the background of COVID-19 vaccine nationalism, with the latter only very weakly resisted by supranational organisations like the World Health Organisation. Concerning the second question: how we can demasculinise the ‘vertical politics of loneliness’, a few things have to be considered. The first issue is to make more visible masculine practices that establish cultural hegemony and try to turn women into ‘nice girls’ (Ellen Willis) whose political role is passive, and whose freedom is taken away through mechanisms of the ‘management of female loneliness’ (with side-effects like the objectification and commodification of women). Another important thing, in my view, is to ‘extract’ from our routines the ‘male gaze’[12] that monopolises our optics of loneliness studies. The same ‘male gaze’ also underpins and reinforces what Marysia Zalewski described as ‘masculine methods’, which might not necessarily be the best ones to reflect our reality. In my view, an alternative methodology of loneliness research can include the epistemology of interpretivism (including, for example Michael Shapiro’s postpositivist analysis of war films and photos). Another way to explore the horizontal politics of loneliness is by conducting autoethnographic writing (including fiction) and in this way building positive ties of solitude (and intimacy) together with colleagues across the globe. Certainly, the 2022 military escalation of conflict in Ukraine only proves that the existential foundations of sovereigntism and its deep links with attempts to overcome ‘geopolitical loneliness’ anxiety both on the domestic and international arena must be considered very seriously. The analysis of political discourse and the ‘politics of loneliness’ during these events is to become a subject of new upcoming research. However, it is evident that we are entering a period when new ‘bubbles’ of ontological insecurities create the conditions for more complicated ideological manipulations with human loneliness anxiety. The new manifestations of sovereigntisms during the current international crisis are unfortunately only likely to provide a wealth of new empirical data for new analysis in the near future. [1] S. Akopov. Sovereignty as ‘organized loneliness’: an existential approach to the sovereigntism of Russian ‘state-civilization’, Journal of Political Ideologies, (published on line October 25, 2021). DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2021.1990560 [2] L. Gudkov. ‘Kto I kak golosoval za popravki v Konstituciyu: zavershaushii opros’, Yuri Levada Analytical Centre, July 8 2020 https://www.levada.ru/2020/08/07/kto-i-kak-golosoval-za-popravki-v-konstitutsiyu-zavershayushhij-opros/, [11 November 2020]. [3] ‘Odinochestvo, i kak s nim borot’sya?,’ Russia’s Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM), February 15 2018, https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=116698, [12 November 2020]. [4] F. Berenskoetter ‘Approaches to Concept Analysis.’ Millennium: Journal of International Studies 45 (2), 2016. p. 151 [5] B. Mijuskoviс Loneliness in Philosophy, Psychology, and Literature. Bloomington: iUniverse, 2012.p. xl. [6] For example, Subotić, Jelena, and Filip Ejdus. “Towards the existentialist turn in IR: introduction to the symposium on anxiety.” Journal of international relations and development, 1-6. 24 Aug. 2021, doi:10.1057/s41268-021-00233-z [7] See, for instance, P. Spiro, ‘The New Sovereigntists: American Exceptionalism and Its False Prophets, Foreign affairs, 79(6), (2000), pp. 9-15; M. Freeden, ‘After the Brexit referendum: revisiting populism as an ideology’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 22 (1), (2017), pp. 4-5. [8] C. Weber, ‘Reconsidering Statehood: Examining the Sovereignty/Intervention Boundary,’ Review of International Studies 18 (3), (1992), p. 216 [9] A. Levi, ‘The Meaning of Existentialism for Contemporary International Relations’. Ethics, 72 (4) (1962), p. 234 [10]. Umbach and Humphrey, ibid., p. 39. [11] V. Surkov, ‘The Loneliness of the Half-Breed’, Russia in Global Affairs (2), March 28 2018, Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/book/The-Loneliness-of-the-Half-Breed-19575, [14 November 2020]. [12] C. Masters. 2016. Handbook on Gender in World Politics. Steans, J. & Tepe-Belfrage, D. (eds.). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, p.322. by Feng Chen

Ideology has been a central force shaping labour movements across the world. However, the role of ideologies in labour activism in contemporary China has received scant scholarly attention. Previous studies on Chinese labour tend to hold that in China’s authoritarian political context, ideologically driven labour activities have rarely existed because they are politically risky; they also assume that ideologies are only related to organised labour movements, which are largely absent in the country. In contrast to these views, I argue that ideologies are important for understanding Chinese labour activism and, in fact, account for the emergence of different patterns of labour activism.

By applying framing theory, this piece examines how ideologies shape the action frames of labour activism in China. Social movements construct action frames by drawing from their societies’ multiple cultural stocks, such as religions, beliefs, traditions, myths, narratives, etc.; ideologies are one of the primary sources that provide ideational materials for the construction of frames. However, frames do not grow automatically out of ideologies. Constructing frames entails processing the extant ideational materials and recasting them into narratives providing “diagnosis” (problem identification and attribution) and “prognosis” (the solutions to problems). Framing theory is largely built on the experiences of Western (i.e., Euro-American) social movements. When social movement scholars acknowledge that action frames can be derived from extant ideologies, they assume that movements have multiple ideational resources from which to choose when constructing their action frames. Movement actors in liberal societies may construct distinct action frames from various sources of ideas, which may even be opposed to each other. Differing ideological dispositions lead to different factions within a movement. Nevertheless, understanding the role of ideology in Chinese labour activism requires us to look into the framing process in an authoritarian setting. In this context, the state’s ideological control has largely shut out alternative interpretations of events. It is thus common for activists to frame and legitimise their claims within the confines of the official discourse in order to avoid the suspicion and repression of the state. Nevertheless, the Chinese official ideology has become fragmented since the market reforms of the late 1970s and 1980s, becoming broken into a set of tenets mixed with orthodox, pragmatic, and deviant components, as a result of incorporating norms and values associated with the market economy. From Deng Xiaoping’s “Let some people get rich first”, the “Socialist market economy” proposed by the 14th National Congress of the CCP, to Jiang Zeming’s “Three Represents”, the party’s official ideology has absorbed various ideas associated with the market economy, though it has retained its most fundamental tenets (i.e., upholding the Party Leadership, Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought, Socialism Road, and Proletariat Dictatorship) crucial for regime legitimacy. Correspondingly, China’s official ideology on labour has since evolved into three strands of discourse: (1) Communist doctrines about socialism vs. capitalism as well as the status of the working-class. (2) Rule of law discourse, which highlights the importance of laws in regulating labour relations and legal procedures as the primary means to protect workers’ individual rights regarding contracts, wages, benefits, working conditions, and so on. (3) The notions of collective consultation, tripartism, and the democratic management of enterprises. These notions are created to address collective disputes arising from market-based labour relations and maintain industrial peace. These three strands of the official discourse, which are mutually conflicting in many ways, reflect the changes as well as the continuity within Chinese official ideology on labour. Framing Chinese labour ideology The fragmentation of the official ideology provides activists with opportunities to selectively exploit it to construct their action frames around labour rights, which have produced moderate, liberal, and radical patterns of labour activism. To be sure, as there is no organised labour movement under China's authoritarian state, the patterns of labour activism should not be understood in strict organisational terms, or as factions or subgroups that often exist within labour movements in other social contexts. The terms are heuristic, and should be used to map and describe scattered and discrete activities that try to steer labour resistance toward different directions. Moderate activism, while embracing the market economy, advocates the protection of workers’ individual rights stipulated by labour laws, and seeks to redress workers’ grievances through legal proceedings. One might object to regarding this position as ideological—after all, it only focuses on legal norms and procedures. However, from the perspective of critical labour law, it can be argued that labour law articulates an ideology, as it aims to legitimate the system of labour relations that subjects workers to managerial control.[1] Moreover, moderates’ adherence to officially sanctioned grievance procedures restrains workers' collective actions and individualises labour disputes, which serves the purpose of the state in controlling labour. Radical activism is often associated with leftist leanings and calls for the restoration of socialism. Radical labour activists have expressed their views on labour in the most explicit socialist/communist or anti-capitalist rhetoric. They condemn labour exploitation in the new capitalistic economy and issue calls to regain the rights of the working class through class struggle. Unsurprisingly, such positions are more easily identified as ideological than others. Liberal activists advocate collective bargaining and worker representation. They are liberal in the sense that their ideas echo the view of “industrial pluralism” that originated in Western market economies. This view envisions collective bargaining as a form of self-government within the workplace, in which management and labour are equal parties who jointly determine the condition of the sale of labour-power.[2] Liberals have also promoted a democratic practice called “worker representation” to empower workers in collective bargaining. To make their action frames legitimate within the existing political boundaries, each type of activist group has sought to appropriate the official discourse through a specific strategy of “framing alignment”.[3] Moderate Activism: Accentuation and Extension Accentuation refers to the effort to “underscore the seriousness and injustice of a social condition”.[4] Movement activists punctuate certain issues, events, beliefs, or contradictions between realities and norms, with the aim of redressing problematic conditions. Moderate labour activists have taken this approach. Adopting a position that is not fundamentally antagonistic to the market economy and state labour policies, they seek to protect and promote workers’ individual rights within the existing legal framework, and correct labour practices where these deviate from existing laws. Thus, their frame is constructed by accentuating legal rights stipulated by labour laws and regulations and developing a legal discourse on labour standards. Moderate activists’ diagnostic narrative attributes labour rights abuses to poor implementation of labour laws, as well as workers’ lack of legal knowledge. Their prognostic frame calls for effective implementation of labour laws and raising workers' awareness of their rights. Extension involves a process that extends a frame beyond its original scope to include issues and concerns that are presumed to be important to potential constituents.[5] Some moderate activists have attempted to extend workers’ individual labour rights to broad “citizenship rights”, which mainly refer to social rights in the Chinese context, stressing that migrant workers’ plight is rooted in their lack of citizenship rights—the rights only granted to urban inhabitants. They advocate social and institutional reforms for fair and inclusionary policies toward migrant workers. While demand for citizenship rights can be seen as moderate in the sense that they are just an extension of individual rights, it contains liberal elements, because such new rights will inevitably entail institutional changes. To extend rights protection beyond the legal arena, moderate activists are instrumental in disseminating the idea of “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) and promoting it to enterprises. This aims to protect workers’ individual rights by disciplining enterprises and making them comply with labour standards. Liberal Activism: Bridging Frame bridging refers to the linking of two or more narratives or movements that have a certain affinity but have been previously formally unconnected. While the existing literature has paid more attention to “ideologically congruent but structurally unconnected frames regarding a particular issue or problem”,[6] “bridging” can also be understood as a means of “moral cover”.[7] That is, it splices alternative views to the official discourse, as a way of creating legitimacy for the former. This is a tactic that China’s liberal labour activism has used fairly frequently. Liberals support market reforms and seek to improve workers’ conditions within the current institutional framework, but they differ from moderates in that their diagnostic narrative attributes workers’ vulnerable position in labour relations to their absence of collective rights. Meanwhile, their prognostic narrative advocates collective bargaining, worker representation, and collective action as the solution to labour disputes. The ideas liberal activists promote largely come from the experiences of Western labour movements and institutional practices. As a rule, the Chines government regards these ideas as unsuited to China’s national conditions. To avoid being labelled as embracing “Western ideology”, liberal activists try to bridge these ideas and practices with China’s official notions of collective consultation, tripartism, and enterprise democracy, justifying workers’ collective role in labour disputes by extensive references to the provisions of labour laws, the civil law, and official policies. These are intended to legitimise their frame as compatible with the official discourse. Radical Activism: Amplification Amplification involves a process of idealising, embellishing, clarifying, or invigorating existing values or beliefs.[8] While the strategy may be necessary for most movement mobilisations, “it appears to be particularly relevant to movements reliant on conscience constituents”.[9] In the Chinese context, radical activists are typically adherents of the orthodox doctrines of the official ideology, either because they used to be beneficiaries of the system in the name of communism or they are sincerely committed to communist ideology in the Marxist conception. Unlike moderates and liberals, who do not oppose the market economy, radicals’ diagnostic frames point to the market economy as the fundamental cause of workers’ socioeconomic debasement. They craft the “injustice frame” in terms of the Marxian concept of labour exploitation, and their prognostic frame calls for building working-class power and waging class struggles. Although orthodox communist doctrines have less impact on economic policies, they have remained indispensable for regime legitimacy. Radical activists capture them as a higher political moral ground on which to construct their frames. Their amplification of the ideological doctrines of socialism, capitalism, and the working class not only provide strong justification for their claims in terms of their consistency with the CCP’s ideological goal; it is also a way of forcefully expressing the view that current economic and labour policies have deviated from the regime’s ideological promises. Conclusion These three action frames have offered their distinct narratives of labour rights (i.e., in terms of the individual, collective, and class), and attributed workers’ plights to the lack of these rights as well as proposing strategies to realise them. However, this does not mean that the three action frames are mutually exclusive. All of them view Chinese workers as being a socially and economically disadvantaged group and stress the crying need to protect individuals’ rights through legal means. Both moderates and liberals support market-based labour relations, while both liberals and radicals share the view that labour organisations and collective actions are necessary to protect workers’ interests. For this reason, however, moderates have often regarded both liberals and radicals as “radical”, as they see their conceptions of collective actions as fundamentally too confrontational. On the other hand, it is not surprising that in the eyes of liberals, radicals are “true” radicals, in the sense that they regard their goals as idealistic and impractical. It is also worth noting that activist groups have tended to switch their action frame from one to another. Some groups started with the promotion of individual rights but later turned into champions for collective rights. The three types of labour activism reflect the different claims of rights that have emerged in China’s changing economic as well as legal and institutional contexts. While the way that labour activists have constructed their frames indicates the common political constraints facing labour activists, their emphasis on different categories of labour rights and strategies to achieve them demonstrates that they did not share a common vision about the structure and institutions of labour relations that would best serve workers’ interests. The lack of a meaningful public sphere under tight ideological control has discouraged debates and dialogues across different views on labour rights and labour relations. Activists with different orientations have largely operated in isolation, and often view other groups as limited and unrealistic—a symptom of the sheer fragmentation of Chinese labour activism. Yet the evidence shows that, although they have resonated with workers to a varying degree, these three patterns of activism have faced different responses from the government because of their different prognostic notions. Both liberal and radical activism have been met with state suppression, because of their advocacy of collective action and labour organising. Their fate attests to the fundamental predicament facing labour movements in China. [1] For this perspective, see J. Conaghan, ‘Critical Labour Law: The American Contribution’, Journal of Law and Society, 14: 3 (1987), pp. 334-352. [2] K. Stone, ‘The Structure of Post-War Labour Relations’, New York University Review of Law and Social Change, 11 (1982), p. 125. [3] R. Benford and D. Snow, ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment’, Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp. 611–639. [4] S. Tarrow, Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012). [5] R. Benford and D. Snow, ‘Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment’, Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp. 611–639. [6] Ibid. [7] D. Westby, ‘Strategic Imperative, Ideology, and Frames.” In Hank Johnstone and John Noakes (Eds.), Frames of Protest (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), pp. 217–236. [8] R. Benford and D. Snow, “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp.611–639. [9] Ibid. 29/4/2021 Alternative logics of ethnonationalism: Politics and anti-politics in Hindutva ideologyRead Now by Anuradha Sajjanhar

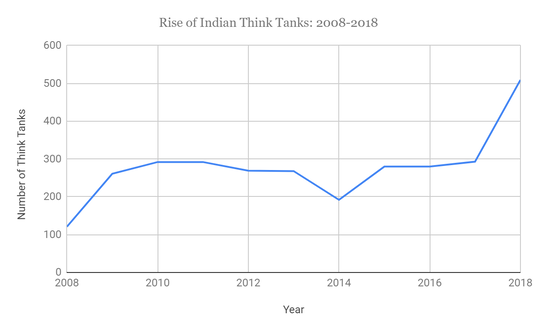

As in most liberal democracies, India’s national political parties work to gain the support of constituencies with competing and often contradictory perspectives on expertise, science, religion, democratic processes, and the value of politics itself. Political leaders, then, have to address and/or embody a web of competing antipathies and anxieties. While attacking left and liberal academics, universities, and the press, the current, Hindu-nationalist Indian government is building new institutions to provide authority to its particular historically-grounded, nationalist discourse. The ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, and its grassroots paramilitary organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), have a long history of sustained Hindu nationalist ideology. Certain scholars see the BJP moving further to the centre through its embrace of globalisation and development. Others argue that such a mainstream economic stance has only served to make the party’s ethno-centric nationalism more palatable. By oscillating between moderation and polarisation, the BJP’s ethno-nationalist views have become more normalised. They have effectively moved the centre of political gravity further to the right. Periods of moderation have allowed for democratic coalition building and wider resonance. At the same time, periods of polarisation have led to further anti-Muslim, Hindu majoritarian radicalisation. This two-pronged dynamic is also present in the Hindu Right’s cultivation of intellectuals, which is what my research is about. Over the last five to ten years, the BJP has been discrediting, attacking, and replacing left-liberal intellectuals. In response, alternative “right-wing” intellectuals have built a cultural infrastructure to legitimate their Hindutva ideology. At the same time, technical experts associated with the government and its politics project the image of apolitical moderation and economic pragmatism. The wide-ranging roles of intellectuals in social and political transformation beg fundamental questions: Who counts as an intellectual and why? How do particular forms of expertise gain prominence and persist through politico-economic conjunctures? How is intellectual legitimacy redefined in new political hegemonies? I examine the creation of an intellectual policy network, interrogating the key role of think tanks as generative proselytisers. Indian think tanks are still in their early stages, but have proliferated over the last decade. While some are explicit about their political and ideological leanings, others claim neutrality, yet pursue their agenda through coded language and resonant historical nationalist narratives. Their key is to effect a change in thinking by normalising it. Six years before winning the election in 2014, India’s Hindu-nationalist party, the BJP, put together its own network of policy experts from networks closely affiliated to the party. In a national newspaper, the former vice-president of the BJP described this as an intentional shift: from “being action-oriented to solidifying its ideological underpinnings in a policy framework”.[1] When the BJP came to power in 2014, people based in these think tanks filled key positions in the central government. The BJP has since been circulating dominant ideas of Hindu supremacy through regional parties, grassroots political organisations, and civil society organisations. The BJP’s ideas do not necessarily emerge from think tank intellectuals (as opposed to local leaders/groups), but the think tanks have the authority to articulate and legitimate Hindu nationalism within a seemingly technocratic policy framework. As primarily elite organisations in a vast and diversely impoverished country, a study of Indian think tanks begs several questions about the nature of knowledge dissemination. Primarily, it leads us to ask whether knowledge produced in relatively narrow elite circles seeps through to a popular consciousness; and, indeed, if not, what purpose it serves in understanding ideological transformation. While think tanks have become an established part of policy making in the US and Europe, Indian think tanks are still in their early stages. The last decade, however, has seen a wider professionalisation of the policy research space. In this vein, think tanks have been mushrooming over the last decade, making India the country with the second largest number of think tanks in the world (second only to the US). As evident from the graph below, while there were approximately 100 think tanks in 2008, they rose to more than 500 in 2018. The number of think tanks briefly dropped in 2014—soon after Modi was elected, the BJP government cracked down on civil society organisations with foreign funding—but has risen dramatically between 2016 and 2018. Fig. 1: Data on the rise of Indian think tanks from Think Tank Initiative (University of Pennsylvania) There are broadly three types of think tanks that are considered to have a seat at the decision-making table: 1) government-funded/affiliated to Ministries; 2) privately-funded; 3) think tanks attached to political parties (these may not identify themselves as think tanks but serve the purpose of external research-based advisors).[2] I do not claim a causal relationship between elite think tanks and popular consciousness, nor try to assert the primacy of top-down channels of political mobilisation above others. Many scholars have shown that the BJP–RSS network, for example, functions both from bottom-up forms of mobilisation and relies on grassroots intellectuals, as well as more recent technological forms of top-down party organisation (particularly through social media and the NaMo app, an app that allows the BJP’s top leadership to directly communicate with its workers and supporters). While the RSS and the BJP instil a more hierarchical and disciplinary party structure than the Congress party, the RSS has a strong grassroots base that also works independent of the BJP’s political elite.

It is important to note that what I am calling the “right-wing” in India is not only Hindu nationalists—the BJP and its supporters are not a coherent, unified group. In fact, the internal strands of the organisations in this network have vastly differing ideological roots (or, rather, where different strands of the BJP’s current ideology lean towards): it encompasses socially liberal libertarians; social and economic conservatives; firm believers in central governance and welfare for the “common man”; proponents of de-centralisation; followers of a World Bank inspired “good governance” where the state facilitates the growth of the economy; believers in a universal Hindu unity; strict adherers to the hierarchical Hindu traditionalism of the caste system; foreign policy hawks; principled sceptics of “the West”; and champions of global economic participation. Yet somehow, they all form part of the BJP–RSS support network. Mohan Bhagwat, the leader of the RSS, has tried to bridge these contradictions through a unified hegemonic discourse. In a column entitled “We may be on the cusp of an entitled Hindu consensus” from September 2018, conversative intellectual Swapan Dasgupta writes of Bhagwat: “It is to the credit of Bhagwat that he had the sagacity and the self-confidence to be the much-needed revisionist and clarify the terms of the RSS engagement with 21st century India...Hindutva as an ideal has been maintained but made non-doctrinaire to embrace three unexceptionable principles: patriotism, respect for the past and ancestry, and cultural pride. This, coupled with categorical assertions that different modes of worship and different lifestyles does not exclude people from the Hindu Rashtra, is important in reforging the RSS to confront the challenges of an India more exposed to economic growth and global influences than ever before. There is a difference between conservative and reactionary and Bhagwat spelt it out bluntly. Bhagwat has, in effect, tried to convert Hindu nationalism from being a contested ideological preoccupation to becoming India’s new common sense.” As Dasgupta lucidly attests, the project of the BJP encompasses not just political or economic power; rather, it attempts to wage ideological struggle at the heart of morality and common sense. There is no single coherent ideology, but different ideological intentions being played out on different fronts. While it is, at this point, difficult to see the pieces fitting together cohesively, the BJP is making an attempt to set up a larger ideological narrative under which these divergent ideas sit: fabricating a new understanding of belonging to the nation. This determines not just who belongs, but how they belong, and what is expected in terms of conduct to properly belong to the nation. I find two variants of the BJP’s attempts at building a new common sense through their think tanks: actively political and actively a-political. In doing so, I follow Reddy’s call to pay close attention to the different ‘vernaculars’ of Hindutva politics and anti-politics.[3] Due to the elite centralisation of policy making culture in New Delhi, and the relatively recent prominence of think tanks, their internal mechanisms have thus far been difficult to access. As such, these significant organisations of knowledge-production and -dissemination have escaped scholarly analysis. I fill this gap by examining the BJP’s attempt to build centres of elite, traditional intellectuals of their own through think tanks, media outlets, policy conventions, and conferences by bringing together a variety of elite stakeholders in government and civil society. Some scholars have characterised the BJP’s think tanks as institutions of ‘soft Hindutva’, that is, organisations that avoid overt association with the BJP and Hindu nationalist linkages but pursue a diffuse Hindutva agenda (what Anderson calls ‘neo-Hindutva’) nevertheless.[4] I build on these preliminary observations to examine internal conversations within these think tanks about their outward positioning, their articulation of their mission, and their outreach techniques. The double-sidedness of Hindutva acts as a framework for understanding the BJP’s wide-ranging strategy, but also to add to a comprehension of political legitimacy and the modern incarnation of ethno-nationalism in an era defined by secular liberalism. The BJP’s two most prominent think tanks (India Foundation and Chanakya Institute), show how the think tanks negotiate a fine balance between projecting a respectable religious conservatism along with an aggressive Hindu majoritarianism. These seemingly contradictory discourses become Hindutva’s strength. They allow it to function as a force that projects aggressive majoritarianism, while simultaneously claiming an anti-political ‘neutral’ face of civilisational purity and inter-religious inclusion. While some notions of ideology understand it as a systematic and coherent body of ideas, Hodge’s concept of ‘ideological complexes’ suggests that contradiction is key to how ideology achieves its effects. As Stuart Hall has shown, dominant and preferred meanings tend to interact with negotiated and oppositional meanings in a continual struggle.[5] Thus, as Hindutva becomes a mediating political discourse, it may risk incoherence, yet defines the terms through which the socio-political world is discussed. The BJP’s think tanks, then, attempt to legitimise its ideas and policies by building a base of both seemingly-apolitical expertise and what they call ‘politically interventionist’ intellectuals. Neo-Hindutva can thus be both explicitly political and anti-political at the same time: advocating for political interventionism while eschewing politics and forging an apolitical route towards cultural transformation. However, contrary to critical scholarship that tends to subsume claims of apolitical motivation within forms of false-consciousness or backdoor-politics, I note that several researchers at these organisations do genuinely see themselves as conducting apolitical, academic research. Rather than wilful ignorance, their acknowledgement of the organisation’s underlying ideology understands the heavy religious organisational undertones as more cultural than political. This distinction takes the cultural and religious parts of Hindutva ‘out of’ politics, allowing it to be practiced and consumed as a generalisable national ethos. [1] Nistula Hebbar, “At Mid-Term, Modi’s BJP on Cusp of Change.” The Hindu. The Hindu, June 12, 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/politics-and-policy/at-mid-term-modis-bjp-on-cusp-of-change/article18966137.ece [2] Anuradha Sajjanhar, “The New Experts: Populism, Technocracy, and the Politics of Expertise in Contemporary India”, Journal of Contemporary Asia (forthcoming 2021). [3] Deepa S. Reddy, “What Is Neo- about Neo-Hindutva?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 483–90. [4] Edward Anderson and Arkotong Longkumer. “‘Neo-Hindutva’: Evolving Forms, Spaces, and Expressions of Hindu Nationalism.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 371–77. [5] Stuart Hall, “Encoding/decoding.” Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks 16676 (2001). |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed