by Fabio Wolkenstein

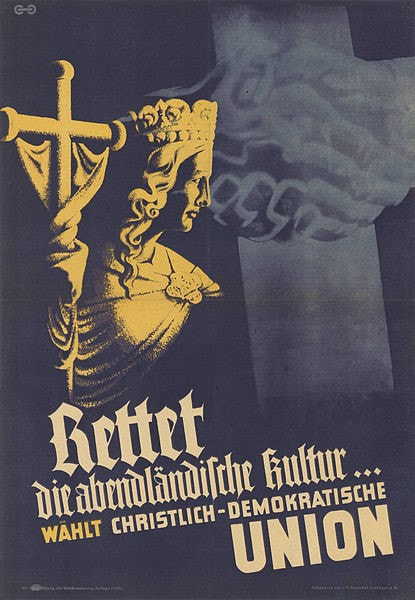

One of the more interesting political developments in contemporary Europe is the migration of the language that has originally been used to describe what Europe is. This language has migrated from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, who were committed to unifying Europe and creating a more humane political order on the continent, to the speeches and campaigns of nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. The idea of “Christian Europe” Consider to start with the notion of Abendland, which may be translated as “occident” or, more accurately, “Christian West.” In the immediate post-war era, the term had been a shorthand for Europe in the predominantly Catholic Christian-democratic milieu whose political representatives played a central role in the post-war unification of Europe; indeed, the “founding fathers” of European integration, Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi, were convinced that – as De Gasperi put it in a 1954 speech – “Christianity lies at the origin of … European civilisation.”[1] By Christianity was primarily meant a common European cultural heritage. De Gasperi, an Italian educated in Vienna around 1900, whose first political job was in the Imperial Council of Austria-Hungary, spoke of a “shared ethical vision that fosters the inviolability and responsibility of the human person with its ferment of evangelic brotherhood, its cult of law inherited from the ancients, its cult of beauty refined through the centuries, and its will for truth and justice sharpened by an experience stretching over more than a thousand years.”[2] All of this, many Christian Democratic leaders thought, demarcates Europe from the superficial consumerism of the United States – however welcome the help of the American allies was after WW2 – and, even more importantly, the materialist totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. Europe is culturally distinctive, and that distinctiveness must be affirmed and preserved to unite the continent at avoid a renewed descent into chaos. This image of Europe figured prominently in the Christian Democrats’ early election campaigns. In 1946, a campaign poster of the newly-founded Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) featured the slogan “Rettet die abendländische Kultur” – “Save abendländische culture.” The poster boasts a bright depiction of the allegorical figure Ecclesia from Bamberg Cathedral, which is meant to represent the superiority of the Church. And Ecclesia faces the logo of the SED, the East German Communist Party, which was founded the same year. The message was clear: a democracy “rooted in the Christian-abendländisch worldview, in Christian natural law, in the principles of Christian ethics,” as Adenauer himself put it in a famous speech at the University of Cologne, had to be cultivated and defended against so-called “materialist” worldviews that represented nothing less than the negation of Christian principles, and by extension the negation of moral truth. In Adenauer’s view, Europe was “only possible” if the different peoples of Europe came together to contribute not only economically to recovering from the war, but also culturally to “abendländisch thinking, poetry.”[3]

This idea of Europe also resonated with General Charles De Gaulle, who served as the first French president after the founding of the Fifth Republic, and who became a natural ally for Adenauer and German Catholic Christian Democrats. De Gaulle certainly had a more nation-centric vision of European integration than Adenauer, and he resisted the idea that supranational institutions should play a central role in the integration processes – but he likewise envisioned a concert of European peoples that shared a common Christian civilisation. These nations should, in De Gaulle’s words, become “an extension of each other,” and their shared cultural roots should facilitate this process. The Italian historian Rosario Forlenza aptly summarised De Gaulle’s views on Europe as follows: “When le général famously spoke of a Europe ‘from the Atlantic to the Urals’ he was in fact conjuring up, quite in line with the Abendland tradition, a continental western European bloc based on a Franco-German entente that could stand on its own both militarily and politically: a Europe independent from the United States and Russia.”[4] In his memoirs, moreover, De Gaulle asserted that the European nations have “the same Christian origins and the same way of life, linked to one another since time immemorial by countless ties of thought, art, science, politics and trade.”[5] No wonder many Christian Democrats saw Gaullism as “a kind of Christian Democracy without Christ.”[6] European integration from shared culture to markets However, those political leaders who conceived Europe as a cultural entity were gradually disappearing. De Gasperi died already in 1954, Adenauer died in 1967, and De Gaulle resigned his presidency in 1969 and died one year later. Robert Schuman, the other famous Christian Democratic “founding father,” who has been put on the path to sainthood by Pope Francis in June 2021, died in 1963. Replacing them were younger and more pragmatic political leaders, many of whom believed that free trade was better able to bring the nations of Europe closer to each other than shared cultural roots.[7] Culture was not considered irrelevant, to be sure – this is why hardly anyone considered admitting a Muslim country like Turkey to the European Communities. But the idea of a Christian Europe whose member countries shared a distinctive heritage, which performed the important function of unifying an earlier generation of centre-right politicians, was gradually superseded by the much less concrete notion of “freedom” as a sort of telos of European integration.[8] Already in the late 1970s, powerful conservative leaders such as Helmut Kohl and Margaret Thatcher converged on the vision that European integration should secure freedom. “Freedom instead of socialism” was the CDU’s 1976 election slogan, which was quite different from “Save abendländische culture” in 1946. Socialism remained the primary enemy – but it should be fought with free markets, not Christian ethics and natural law, as Adenauer believed. Importantly, foregrounding the notion of freedom and de-emphasising thick conceptions of a shared European culture also facilitated the gradual expansion of the pan-European network of conservative parties from the mid-1970s onwards. Transnationally-minded Realpolitiker like Kohl realised already in the mid-1970s that integrating “Christian democratic and conservative traditions and parties” from non-Catholic countries into the European People’s Party and related transnational organisations was crucial to avoid political marginalisation in the constantly expanding European Communities.[9] And many new potential allies, perhaps most notably Scandinavian conservative parties who obviously had no Catholic pedigree, would have shrunk from the idea of joining a Christian Abendland modelled in the image of Charlemagne’s empire. The re-emergence of the language of Christian Europe At any rate, while the language of a Europe defined by shared culture gradually disappeared from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, decades later it re-appeared elsewhere. It was adopted by political actors who are often categorised as “right-wing populists” – more accurately, we might call them nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. These sorts of political movements have discovered and re-purposed the culturalist narrative of a “Christian Europe.” In the German-speaking world, even the notion of Abendland made a comeback on the right fringes. The Alternative für Deutschland (or AfD), Germany’s moderately successful hard-right party, commits itself in its main party manifesto to the “preservation” of “abendländisch Christian culture.”[10] The closely related anti-immigrant movement PEGIDA even has Abendland in its name: the acronym stands for “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamicisation of the Abendland.” The Austrian Freedom Party, one of the more long-standing ultraconservative nationalist parties in Europe, used the Slogan “Abendland in Christenhand,” meaning “Abendland in the hands of Christians” in the 2009 European Elections. Even more striking are the increasing appeals to the idea of Christian Europe that resound in Central and Eastern Europe. The political imaginaries of the likes of Viktor Orbán – the pugnacious Hungarian prime minister who has transformed Hungary into an “illiberal democracy” – and Jarosław Kaczyński and his Polish Law and Justice party, are defined by an understanding of Europe as a culturally Christian sphere. And they claim to preserve and defend this Europe, especially against the superficial, culturally corrosive social liberalism of the West, which they consider a major threat to its shared values and traditions. Orbán even seeks to link the notion of Christian Europe to the ideological tradition of Christian Democracy. Not only has he repeatedly called for a “Christian Democratic renaissance” that should involve a return to the values and ideas of the post-war era.[11] In February 2020, when the European People’s Party – the European alliance of Christian Democratic parties – seemed increasingly willing to expel Orbán’s party Fidesz due to the undemocratic developments in Hungary, he even drafted a three-page memorandum for the European Christian Democrats. In this memorandum, a most remarkable document for anyone interested in political ideologies, he listed all the sort of things that Christian Democrats “originally” stood for – from being “anti-communist” and “pro-subsidiarity” to being “committed representatives … of the Christian family model and the matrimony of one man and one woman.” However, he added, “We have created an impression that we are afraid to declare and openly accept who we are and what we want, as if we were afraid of losing our share of governmental authority because of ourselves.”[12] To save itself, and to save Europe, a return to the ideological roots of Christian Democracy is needed; or so Orbán argued. In sum, the language of Europe as a thick cultural community, the idea of a Christian Europe, and indeed some core elements of the ideology of Christian Democracy itself – all this has migrated to other sectors of the political spectrum and to Eastern Europe. Ideas and concepts that after WWII were part of the centre-right’s ideological repertoire are now used by nativists and ultraconservative nationalists, and used in order to justify their exclusivist Christian identity politics.[13] Note that the Eastern European parties and politicians who today reach for the narrative of Christian Europe stand for a broader backlash against the previously-hegemonic, unequivocally market-liberal and pro-Western forces that made many Western European centre-right leaders enthusiastically support Eastern Enlargement in the early 2000s. For the Polish Law and Justice party not only rejects liberal views about same sex-marriage, abortion, etc.; several of its redistributive policies also mark “a rupture with neoliberal orthodoxy,” and thus a departure from the policies of the business-friendly, pro-EU Civic Platform government of Donald Tusk, which Kaczyński’s party replaced in 2015.[14] In Orbán’s Hungary, free-market policies have largely remained in place – especially when Orbán and his cronies profited from them – yet the recent “renationalisation of the pension system [and] significantly increased spending on active labour market policies … point towards an increasing … role of the state in social protection.”[15] Understanding the migration of language One interesting interpretation of this development frames it in terms of a revolt of Eastern – and indeed Western – European nativists and nationalists against a perceived imperative to be culturally liberal and anti-nationalist. Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes perceptively note that “[t]he ultimate revenge of the Central and East European populists against Western liberalism is not merely to reject the ‘imitation imperative’, but to invert it. We are the real Europeans, Orbán and Kaczyński claim, and if the West wants to save itself, it will have to imitate the East.”[16] While there is much to be learned from this analysis, another reading of the eastward and rightward migration of culturalist understandings of Europe is available. This starts from the observation that talking about Europe as a geographical space defined by a deeply rooted common culture implies talking also about where Europe ends, where its cultural borders lie. Recall that the Europe envisaged by the Christian Democratic “founding fathers” and by De Gaulle was a much smaller, more limited entity than today’s European Union with its 27 member states. They believed, for example, that there were profound cultural differences between the abendländisch, predominantly Catholic Europe and Protestant Britain and Scandinavia. De Gaulle was in fact fervently opposed to admitting Britain to the European Communities and famously vetoed Britain’s applications to join in 1963 and 1967. If talking about Europe in cultural terms necessarily involves talking about cultural boundaries, then it is perhaps not surprising that today’s nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives came to endorse a culturalist understanding of Europe. After all, these are virtually the only political actors who indulge in talking about borders and attribute utmost importance to problematising and politicising cultural difference. Seen in this light, it is only natural that the once-innocuous notion that Europe has, as it were, “cultural borders” finds a home with them. Revisiting the question of European culture One need not endorse the political projects of Viktor Orbán, Jarosław Kaczyński and their allies to acknowledge that the questions they confront us with merit attention. What is Europe, if it is an entity defined by shared culture? And, by extension, where does Europe end? Not only those who simply do not want to leave it up to nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives to define what Europe is, culturally speaking, will need to ponder these questions. Where Europe ends is also a highly pertinent issue in current European geopolitics, and interestingly, it seems as though key EU figures are gradually converging on a position that structurally resembles a view that was prominent on the centre-right in the post-war era – without linking it to narratives about shared culture. Indeed, with the Von der Leyen Commission’s commitment to “strategic autonomy” and the objective to ascertain European sovereignty over China, the original Christian Democratic and Gaullist theme of Europe as independent “third” global power has returned with a vengeance – just that independence today means independence from the United States and China, not the United States and Soviet Russia (though Russia remains a menacing presence).[17] However, whereas De Gaulle and Christian Democratic “Gaullists” saw Europe’s Christian origins and a shared way of life as the backbone of geopolitical autonomy, the President of the Commission limits herself to mentioning the “unique single market and social market economy, a position as the world’s first trading superpower and the world’s second currency” as the sort of things that make Europe distinctive.[18] Much like earlier pragmatically-minded politicians, then, von der Leyen mostly speaks the language of markets – and of moral universalism: “We must always continue to call out human rights abuses,” she routinely insists with an eye to China.[19] But it is doubtful whether human rights talk or free market ideology are sufficient to render plausible claims to “strategic autonomy.” Being by definition boundary-insensitive and global in outlook, they are little able to furnish a convincing argument for why Europe should be more autonomous.[20] Perhaps the notion of “strategic autonomy” is actually much more about a shared European “way of life” than present EU leaders, unlike their post-war predecessors, are willing to admit. Why else would von der Leyen also want to appoint a “vice president for protecting our European way of life,” whilst describing China as “systemic rival” and even cautiously expressing uncertainty about the ally-credentials of post-Trump America? Here, the twin questions of European culture and where Europe ends, come into view again. And it seems by all means worthwhile to speak more about that – without adopting the narrow and exclusionary narratives of Orbán and Kaczyński or wishing for a return to post-war Christian Democracy or Gaullism. [1] Cited in Rosario Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland: Christian Democracy and the Idea of Europe after the Second World War’, Contemporary European History 26(2) (2017), 269. [2] Ibid. [3] Konrad Adenauer, (1946) Rede in der Aula der Universität zu Köln, 24 March 1946. Available at https://www.konrad-adenauer.de/quellen/reden/1946-03-24-uni-koeln, accessed 15 May 2020. [4] Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland’, 270. [5] Charles de Gaulle, Memoirs of Hope: Renewal and Endeavor (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971), 171. [6] Ronald J. Granieri, ‘Politics in C Minor: The CDU/CSU between Germany and Europe since the Secular Sixties’, Central European History 42(1) (2009), 18. [7] Josef Hien and Fabio Wolkenstein, ‘Where Does Europe End? Christian Democracy and the Expansion of Europe’, Journal of Common Market Studies (forthcoming). [8] Martin Steber, Die Hüter der Begriffe: Politische Sprachen des Konservativen in Großbritannien und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1945-1980 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), 410-422. [9] Wolfram Kaiser, Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 316. [10] Alternative für Deutschland, Programm für Deutschland (2016) Available at https://cdn.afd.tools/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2018/01/Programm_AfD_Druck_Online_190118.pdf, accessed 16 September 2020. [11] Cabinet Office of the Hungarian Prime Minister, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s speech at a conference held in memory of Helmut Kohl (16 June 2018), Available at: http://www.miniszterelnok.hu/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-speech-at-a-conference-held-in-memory-of-helmut-kohl/, accessed 10 June 2020. [12] Fidesz, Memorandum on the State of the European People’s Party, February 2020. [13] Olivier Roy, Is Europe Christian? (London: Hurst, 2019), 118-214. [14] Gavin Rae, ‘In the Polish Mirror’, New Left Review 124 (July/Aug 2020), 99. [15] Dorothee Bohle and Béla Greskovits, ‘Politicising embedded neoliberalism: continuity and change in Hungary’s development model’, West European Politics, 1072. [16] Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes, ‘Imitation and its Discontents’, Journal of Democracy 29(3) (2018), 127. [17] Jolyon Howorth, Europe and Biden: Towards a New Transatlantic Pact? (Brussels: Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, 2021). [18] Speech by President von der Leyen at the EU Ambassadors’ Conference 2020, 10 November 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_2064, accessed 22 June 2021. [19] Ibid. [20] As Quinn Slobodian convincingly argues, free market ideology ultimately seeks to achieve a global market with minimal governmental regulations, see Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed