by Peter Staudenmaier

In September 2018, a perceptive article in the left-leaning British magazine New Statesman offered a rare glimpse of the obscure milieu of explicitly racist environmentalism: an anonymous “online community” of “nature-obsessed, antisemitic white supremacists who argue that racial purity is the only way to save the planet.” Made up largely of younger enthusiasts of the far right, this new generation of self-described “eco-fascists” identifies strongly with deep ecology, animal rights, and veganism, opposes industrialisation and urbanisation, and denounces immigration, “overpopulation” and “multiculturalism” as dire threats to the natural world. They celebrate “blood and soil” and look back on Nazi Germany as a paragon of environmental responsibility, casting the Third Reich’s obsession with “Lebensraum” in ecological terms.[1]

Within months, this incongruous ideology burst the boundaries of internet anonymity and made headlines around the world. Two horrific anti-immigrant attacks in 2019, in Christchurch and El Paso, showed that such ideas could have lethal consequences. Both atrocities, which claimed a total of 74 victims, were motivated by environmental concerns. The Christchurch perpetrator declared himself an “eco-fascist.”[2] In the wake of these massacres it became harder to dismiss right-wing ecology as a marginal set of far-fetched beliefs confined to online forums; the combination of environmentalism, nationalism, and anti-immigrant violence proved too virulent to ignore.[3] It nonetheless remains difficult to understand. More thorough consideration of the historical background to right-wing ecology and its contemporary resonance can help make better sense of an enigmatic phenomenon, one that disrupts standard expectations about both environmentalism and right-wing politics. Though environmental issues have been conventionally associated with the left since the 1960s, the longer history of ecological politics is far more ambivalent. From the emergence of modern environmentalism in the nineteenth century, ecological questions have taken either emancipatory or reactionary form depending on their political context.[4] Early conservationists in the United States often held authoritarian, nationalist, and xenophobic views linked with the predominant racial theories of the era. As a standard study observes, “The conservation movement arose against a backdrop of racism, sexism, class conflicts, and nativism that shaped the nation in profound ways.”[5] Already in the 1870s, American environmental writers blamed “the influx of immigrants” for the decline of natural rural life.[6] For eminent figures like George Perkins Marsh and John Muir, racial biases and hostility toward immigration went hand in hand with protecting the natural world.[7] Such stances hardened by the early twentieth century. In his 1913 classic Our Vanishing Wild Life, William Temple Hornaday portrayed immigrants as “a dangerous menace to our wild life.”[8] Hornaday, who has been called the “father of the American conservation movement,” was a friend and colleague of Madison Grant, an equally influential conservationist, race theorist, and zealous proponent of eugenics. Racial anxieties were a constituent element in the development of environmentalism in the US. “Perceiving a direct link between the decline of America’s wildlife and the degeneration of the white American race, prominent nature advocates often pushed as hard for the passage of immigration restriction and eugenics legislation as they did for wildlife preservation. For these reformers the three movements became inextricably linked.”[9] This legacy continued throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, impacting everything from wilderness campaigns to pollution regulation to global population programs. Today, “racial narratives are deeply embedded in American environmentalist approaches to international population policy advocacy.”[10] In Germany, where the term “ecology” was first introduced, early environmental movements shared a similar history. Sometimes considered the homeland of green politics, Germany experienced rapid industrialisation and urbanisation in the decades around 1900, with attendant forms of environmental dissent. Many of these proto-green tendencies incorporated authoritarian social views along with powerful national and racial myths. From vegetarianism to organic agriculture to nature protection organisations, race was an essential part of the search for more natural ways of life.[11] Proponents of the “life reform” movement mixed appeals for animal rights, natural health, and alternative nutrition with racist and antisemitic themes.[12] This is the tradition that latter-day “ecofascists” hope to reclaim.[13] For some contemporary advocates of right-wing ecology, Nazi Germany represents the epitome of environmental ideals in fascist form. In light of the Nazi regime’s appalling record of human and ecological destruction, this adulation strikes many observers as grotesque. As paradoxical as it may seem, however, Nazism included several significant environmental strands. Historians of the Third Reich have increasingly come to recognise “the links between antisemitism, eugenics, and environmentalism that became integral to National Socialism.”[14] To admirers, Nazism’s “green” achievements were embodied above all in the figure of Richard Walther Darré, who served as Hitler’s minister of agriculture and “Reich Peasant Leader” from 1933 to 1942. Far right author Troy Southgate characterises Darré as Nazi Germany’s “finest ecological pioneer,” a committed environmentalist who was “truly the patriarch of the modern Greens.” Southgate writes: "At Goslar, an ancient medieval town in the Harz mountains, Darré established a peasants’ capital and launched a series of measures designed to regenerate German agriculture by encouraging organic farming and replanting techniques. […] But Darré’s overall strategy was even more radical, and he intended to abolish industrial society altogether and replace it with a series of purely peasant-based communities."[15] Though thoroughly distorted, this tale contains a kernel of truth. Darré did promote organic agriculture during the final years of his tenure; after initial opposition, he became one of the major Nazi patrons of the biodynamic movement, the most successful variant of organic farming in the Third Reich.[16] But he was hardly the only Nazi leader to do so. Rudolf Hess supported biodynamics more consistently, and even Heinrich Himmler and the SS sponsored biodynamic projects. By the time he adopted the biodynamic cause, moreover, Darré had effectively lost power to rival factions within the party. Organic farming initiatives nevertheless found many backers in various parts of the Nazi apparatus, at local, regional, and national levels, from interior minister Wilhelm Frick to antisemitic propagandist Julius Streicher. Sustainable agriculture offered fertile ground for ideological crossover and practical cooperation. As a Nazi “life reform” official explained in 1936: “Artificial fertilisers interrupt the natural metabolism between man and his environment, between blood and soil.”[17] Despite his stature among devotees of right-wing ecology today, Darré was not the most effective example of ecofascism in action in the Nazi era. That dubious honor belongs not to the Reich Peasant Leader but to his sometime ally Alwin Seifert, who bore the equally grandiose title of Reich Advocate for the Landscape. Seifert oversaw a corps of “landscape advocates” with responsibility for environmental planning on Nazi public works projects, most famously the construction of the Autobahn system. As with Darré, Seifert’s position has often been misunderstood. A recent account claims that “the barest minima of ecological politics” were “completely missing” from Nazism, offering this description of Seifert’s team: "A group of designers with Heimat ideals, called ‘landscape advocates’, imagined that they were embedding the motorways in the landscape, drawing the curves gently, adorning the concrete and asphalt with local stone and freshly planted native flora: perhaps the original greenwashers. Their advice was neglected nearly all the time, and Hitler would not hear of valuable forest groves slowing down his roads. If any peacetime project rode roughshod over conservation, it was the autobahn."[18] This one-sided image simplifies a complex history and misconstrues the political context. Unlike traditional conservationists, Seifert and his colleagues used their work to advance modern principles of ecological restoration, rehabilitating degraded environments and applying organic techniques across a wide range of landscapes. Their remit extended far beyond the Autobahn, encompassing rivers and wetlands, reforestation projects, urban green space and rural reclamation, military installations, and “settlement” activities in the occupied East. From France to Ukraine, from Norway to Greece, the environmental efforts of the landscape advocates were woven into the fabric of Nazi occupation policy, which aimed to remake Eastern European lands racially as well as ecologically. Under the auspices of the Third Reich, Seifert and his cohort fused environmental ideals with Nazi tenets and put them into practice in hundreds of concrete instances.[19] They were not alone. Endorsing Seifert’s work, German naturalists proclaimed that ecology was “a true science of blood and soil.”[20] The experience of both the biodynamic movement and the landscape advocates between 1933 and 1945, in the shadow of Germany’s war of annihilation, shows that Nazi ecology was not an oxymoron but a historical reality. In spite of a growing body of research examining the details of this history, many misconceptions persist about the environmental aspects of Nazism and about the political evolution of green endeavors worldwide. The problem is not new. A quarter of a century ago, ecological philosopher Michael Zimmerman pointed out that “most Americans do not realise that the Nazis combined eugenics with mystical ecology into the perverted ‘green’ ideology of Blut und Boden.” It was not merely a historical question, he explained, but crucial for our future: “in periods of ecological stress and social breakdown, preachers of a ‘green’ fascism might once again find a sympathetic audience.”[21] The attacks in Christchurch and El Paso have tragically confirmed his point, demonstrating that some of those inspired by such ideas are willing to turn words into deeds. But the breadth of right-wing environmental politics is not reducible to the single category of fascism. Many elements on the established right, particularly in the English-speaking world, maintain a stance of climate change denial and denounce green concerns as frivolous, even as younger and more dynamic forces on the far right push for growing appropriation of environmental themes. In this context, ecofascism is best seen as an especially aggressive tendency within the broader continuum of right-wing ecology.[22] Since most of the right is not fascist, there are relatively few outright ecofascists in most times and places. This does not mean we can safely ignore them. When historical conditions change, currents that were previously marginal can quickly become powerful. For societies like the contemporary US, that is a sobering lesson to keep in mind.[23] How can scholars respond to this challenge? Resisting the revival of blood and soil politics and countering the appeal of anti-immigrant arguments in green garb calls for informed and reflective participation in public debates. This will involve critically re-examining inherited assumptions about ecology and its social significance. The protean nature of environmental politics, viewed in historical perspective, presents a remarkable spectrum of possibilities, and those concerned about the climate crisis and our broader ecological plight will eventually need to decide where to stand. Alongside the legacy of right-wing environmentalism, there has always been a lively counter-current, an anti-authoritarian, inclusive, and radically democratic strand within ecological thought and practice. That alternative tradition of environmental politics has many proponents within today’s climate movement, and it points toward a promising future in spite of the bleak present. An ecological approach that affirms social diversity across borders and actively welcomes all communities can withstand the resentments and anxieties of the current moment. Against the callous retreat into exclusion, scarcity, and fear, it advances a profoundly different vision of sustainability and renewal, one that offers hope for people and for the planet we share. [1] Sarah Manavis, “Eco-fascism: The ideology marrying environmentalism and white supremacy thriving online” New Statesman 21 September 2018. The article signaled renewed media attention to a previously neglected subject. Another thorough analysis was published a month later: Matthew Phelan, “The Menace of Eco-Fascism” New York Review of Books Daily 22 October 2018. [2] Natasha Lennard, “The El Paso Shooter Embraced Eco-Fascism: We Can’t Let the Far Right Co-Opt the Environmental Struggle” The Intercept 5 August 2019; Bernhard Forchtner, “Eco-fascism: Justifications of terrorist violence in the Christchurch mosque shooting and the El Paso shooting” Open Democracy 13 August 2019; Susie Cagle, “The environmentalist roots of anti-immigrant bigotry” The Guardian 16 August 2019; Joel Achenbach, “Two mass murders a world apart share a common theme: ‘Ecofascism’” Washington Post 18 August 2019; Sam Adler-Bell, “Eco-fascism is fashionable again on the far right” New Republic 24 September 2019. [3] For recent international coverage see Neil Mackay, “Eco-fascism: how the environment could be a green light for the far right” The Herald 18 April 2020; Daniel Trilling, “How the far right is exploiting climate change for its own ends: Eco-fascists have donned green garb in pursuit of their sinister cause” Prospect Magazine 28 August 2020; Emma Horan, “Eco-Fascism: A Smouldering, Dark Presence in Environmentalism” University Times 23 October 2020; Louise Boyle, “The rising threat of eco-fascism: Far right co-opting environmentalism to justify anti-immigration and anti-Semitic views” The Independent 20 March 2021; Francisca Rockey, “The dangers of eco-fascism” Euronews 21 March 2021; Andy Fleming, “The meanings of eco-fascism” Overland 9 June 2021. [4] Adrian Parr, Birth of a New Earth: The Radical Politics of Environmentalism (Columbia University Press 2018), 84; see the full chapter “Fascist Earth” (65-90) for her larger argument. [5] Dorceta Taylor, The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection (Duke University Press 2016), 9. [6] Ibid., 89; see also 213-19 on anti-immigrant resentment as a core feature of the US conservation movement in the early twentieth century. For an influential instance from the latter half of the century see John Tanton, “International Migration as an Obstacle to Achieving World Stability” Ecologist July 1976, 221-27. [7] See the fine overview by Carolyn Merchant, “Shades of Darkness: Race and Environmental History” Environmental History 8 (2003), 380-94. [8] William Temple Hornaday, Our Vanishing Wild Life (Scribner’s 1913), 100. Similar anti-immigrant passages can be found in Hornaday’s 1914 Wild Life Conservation in Theory and Practice. Scholars from a variety of fields have noted the role of racial beliefs within his environmental worldview: “Hornaday’s conservation was closely linked to his racism and sense of Anglo-Saxon superiority. He viewed Native Americans, Mexicans, blacks, and immigrants as major threats to wildlife, and he began showing disdain for nonwhites early in his career.” Robert Wilson, American Association of Geographers Review of Books 2 (2014), 48-50. [9] Miles Powell, Vanishing America: Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation (Harvard University Press 2016), 83. Powell shows that turn of the century conservation leaders “developed racially charged preservationist arguments that influenced the historical development of scientific racism, eugenics, immigration restriction, and population control, and helped lay the groundwork for the modern environmental movement.” (5) Compare Lisa Sun-Hee Park and David Naguib Pellow, The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants vs. the Environment in America’s Eden (New York University Press 2011); John Hultgren, Border Walls Gone Green: Nature and Anti-Immigrant Politics in America (University of Minnesota Press 2015); Carl Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (New York University Press 2016) [10] Jade Sasser, “From Darkness into Light: Race, Population, and Environmental Advocacy” Antipode 46 (2014), 1240-57, quote on 1242. Cf. Jael Silliman and Ynestra King, eds., Dangerous Intersections: Feminist Perspectives on Population, Environment, and Development (South End Press 1999); Rajani Bhatia, “Green or Brown? White Nativist Environmental Movements” in Abby Ferber, ed., Home-Grown Hate: Gender and Organized Racism (Routledge 2004), 194-213; Jade Sasser, On Infertile Ground: Population Control and Women’s Rights in the Era of Climate Change (New York University Press 2018); Jordan Dyett and Cassidy Thomas, “Overpopulation Discourse: Patriarchy, Racism, and the Specter of Ecofascism” Perspectives on Global Development & Technology 18 (2019), 205-24; Diana Ojeda, Jade Sasser, and Elizabeth Lunstrum, “Malthus’s Specter and the Anthropocene: Towards a Feminist Political Ecology of Climate Change” Gender, Place & Culture 27 (2020), 316-32. [11] Examples include Gustav Simons, “Rasse und Ernährung” Kraft und Schönheit 4 (1904), 156-59; Hermann Löns, “Naturschutz und Rasseschutz” in Löns, Nachgelassene Schriften vol. 1 (Leipzig 1928), 486-91; Paul Krannhals, Das organische Weltbild (Munich 1928); Werner Altpeter, “Erneuerung oder Rassetod?” Neuform-Rundschau January 1934, 8-10. [12] Compare Joseph Huber, “Fortschritt und Entfremdung: Ein Entwicklungsmodell des ökologischen Diskurses” in Dieter Hassenpflug, ed., Industrialismus und Ökoromantik: Geschichte und Perspektiven der Ökologisierung (Wiesbaden 1991), 19-42; Ulrich Linse, “Das ‘natürliche’ Leben: Die Lebensreform” in Richard van Dülmen, ed., Erfindung des Menschen (Vienna 1998), 435-56; Bernd Wedemeyer, “‘Zurück zur deutschen Natur’: Theorie und Praxis der völkischen Lebensreformbewegung” in Rolf Brednich, ed., Natur – Kultur: Volkskundliche Perspektiven auf Mensch und Umwelt (Münster 2001), 385-94; Jost Hermand, “Die Lebensreformbewegung um 1900 - Wegbereiter einer naturgemäßeren Daseinsform oder Vorboten Hitlers?” in Marc Cluet and Catherine Repussard, eds., “Lebensreform”: Die soziale Dynamik der politischen Ohnmacht (Tübingen 2013), 51-62. [13] See the extended argument in Peter Staudenmaier, “Right-wing Ecology in Germany: Assessing the Historical Legacy” in Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, Ecofascism Revisited (New Compass 2011), 89-132. [14] Robert Gellately, Hitler’s True Believers: How Ordinary People Became Nazis (Oxford University Press 2020), 22; cf. Simo Laakkonen, “Environmental Policies of the Third Reich” in Laakkonen, ed., The Long Shadows: A Global Environmental History of the Second World War (Oregon State University Press 2017), 55-74; Charles Closmann, “Environment” in Shelley Baranowski, ed., A Companion to Nazi Germany (Wiley 2018), 413-28. [15] Troy Southgate, “Blood & Soil: Revolutionary Nationalism as the Vanguard of Ecological Sanity” in Southgate, Tradition & Revolution (Arktos 2010), 74-84, quotes on 78-79. Southgate’s account draws heavily on the work of Anna Bramwell, whose 1985 book Blood and Soil: Richard Walther Darré and Hitler’s ‘Green Party’ is the source of a number of legends about Darré. Among other fundamental problems, Bramwell’s book downplays Darré’s fervent antisemitism and denies his role in promoting expansionist aims in Eastern Europe. [16] Peter Staudenmaier, “Organic Farming in Nazi Germany: The Politics of Biodynamic Agriculture, 1933-1945” Environmental History 18 (2013), 383-411. [17] Franz Wirz quoted in Corinna Treitel, Eating Nature in Modern Germany: Food, Agriculture and Environment, c. 1870-2000 (Cambridge University Press 2017), 212. Nazi enthusiasm for organic practices was not as surprising as it may appear. “In early twentieth century Germany,” Treitel notes, “ecological agriculture and its biological approach to farming belonged decisively to the right.” (188) The same pattern can be traced in France, Britain, Australia, and elsewhere, with significant overlap between the early organic milieu and the far right. [18] Andreas Malm and the Zetkin Collective, White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism (Verso 2021), 462 and 466. They insist that “no ecological Nazism could possibly have existed” (470). [19] For a detailed view of the current state of research see Peter Staudenmaier, “Advocates for the Landscape: Alwin Seifert and Nazi Environmentalism” German Studies Review 43 (2020), 271-90. Some of the existing scholarship on Seifert and his associates displays a curious tendency to portray these figures as either not really environmentalists or not really Nazis, reluctant to acknowledge that they were both at once. [20] Karl Friederichs, Ökologie als Wissenschaft von der Natur (Leipzig 1937), 79. [21] Michael Zimmerman, “The Threat of Ecofascism” Social Theory and Practice 21 (1995), 207-38, quotes on 222 and 231. “Blut und Boden” is the original German phrase meaning “blood and soil.” [22] As Bernhard Forchtner and Balša Lubarda aptly observe, “eco-fascism should not dominate our understanding of the wider radical right’s relationship with nature.” (Forchtner and Lubarda, “Eco-fascism ‘proper’” Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right 25 June 2020) For a range of perspectives on these complex questions compare Efadul Huq and Henry Mochida, “The Rise of Environmental Fascism and the Securitization of Climate Change” Projections 30 March 2018; Betsy Hartmann, “The Ecofascists” Columbia Journalism Review Spring 2020, 18-19; Hilary Moore, Burning Earth, Changing Europe: How the Racist Right Exploits the Climate Crisis and What We Can Do about It (Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung 2020); Sam Knights, “The Climate Movement Must Be Ready To Challenge Rising Right-Wing Environmentalism” Jacobin 16 November 2020; Balša Lubarda, “Beyond Ecofascism? Far-Right Ecologism as a Framework for Future Inquiries” Environmental Values 29 (2020), 713-32. [23] On the US see Blair Taylor, “Alt-right ecology: Ecofascism and far-right environmentalism in the United States” in Bernhard Forchtner, ed., The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication (Routledge 2019), 275-92; Kevan Feshami, “A Mighty Forest Is Our Race: Race, Nature, and Environmentalism in White Nationalist Thought” Drain Magazine February 2020; Beth Gardiner, “White Supremacy Goes Green” New York Times 1 March 2020; Daniel Rueda, “Neoecofascism: The Example of the United States” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 14 (2020), 95-125; Alex Amend, “Blood and Vanishing Topsoil: American Ecofascism Past, Present, and in the Coming Climate Crisis” Political Research Associates 9 July 2020; April Anson, “No One Is A Virus: On American Ecofascism” Environmental History Now 21 October 2020. by Fabio Wolkenstein

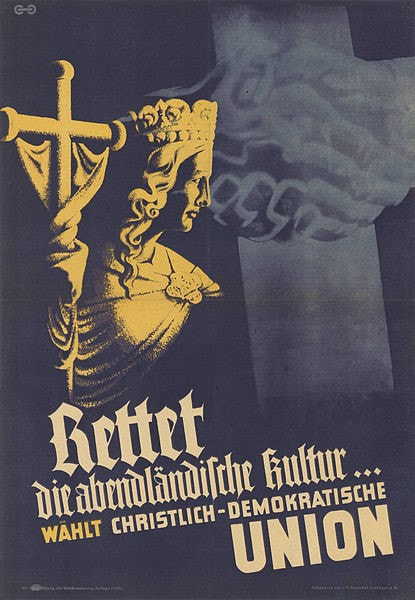

One of the more interesting political developments in contemporary Europe is the migration of the language that has originally been used to describe what Europe is. This language has migrated from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, who were committed to unifying Europe and creating a more humane political order on the continent, to the speeches and campaigns of nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. The idea of “Christian Europe” Consider to start with the notion of Abendland, which may be translated as “occident” or, more accurately, “Christian West.” In the immediate post-war era, the term had been a shorthand for Europe in the predominantly Catholic Christian-democratic milieu whose political representatives played a central role in the post-war unification of Europe; indeed, the “founding fathers” of European integration, Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi, were convinced that – as De Gasperi put it in a 1954 speech – “Christianity lies at the origin of … European civilisation.”[1] By Christianity was primarily meant a common European cultural heritage. De Gasperi, an Italian educated in Vienna around 1900, whose first political job was in the Imperial Council of Austria-Hungary, spoke of a “shared ethical vision that fosters the inviolability and responsibility of the human person with its ferment of evangelic brotherhood, its cult of law inherited from the ancients, its cult of beauty refined through the centuries, and its will for truth and justice sharpened by an experience stretching over more than a thousand years.”[2] All of this, many Christian Democratic leaders thought, demarcates Europe from the superficial consumerism of the United States – however welcome the help of the American allies was after WW2 – and, even more importantly, the materialist totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. Europe is culturally distinctive, and that distinctiveness must be affirmed and preserved to unite the continent at avoid a renewed descent into chaos. This image of Europe figured prominently in the Christian Democrats’ early election campaigns. In 1946, a campaign poster of the newly-founded Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) featured the slogan “Rettet die abendländische Kultur” – “Save abendländische culture.” The poster boasts a bright depiction of the allegorical figure Ecclesia from Bamberg Cathedral, which is meant to represent the superiority of the Church. And Ecclesia faces the logo of the SED, the East German Communist Party, which was founded the same year. The message was clear: a democracy “rooted in the Christian-abendländisch worldview, in Christian natural law, in the principles of Christian ethics,” as Adenauer himself put it in a famous speech at the University of Cologne, had to be cultivated and defended against so-called “materialist” worldviews that represented nothing less than the negation of Christian principles, and by extension the negation of moral truth. In Adenauer’s view, Europe was “only possible” if the different peoples of Europe came together to contribute not only economically to recovering from the war, but also culturally to “abendländisch thinking, poetry.”[3]

This idea of Europe also resonated with General Charles De Gaulle, who served as the first French president after the founding of the Fifth Republic, and who became a natural ally for Adenauer and German Catholic Christian Democrats. De Gaulle certainly had a more nation-centric vision of European integration than Adenauer, and he resisted the idea that supranational institutions should play a central role in the integration processes – but he likewise envisioned a concert of European peoples that shared a common Christian civilisation. These nations should, in De Gaulle’s words, become “an extension of each other,” and their shared cultural roots should facilitate this process. The Italian historian Rosario Forlenza aptly summarised De Gaulle’s views on Europe as follows: “When le général famously spoke of a Europe ‘from the Atlantic to the Urals’ he was in fact conjuring up, quite in line with the Abendland tradition, a continental western European bloc based on a Franco-German entente that could stand on its own both militarily and politically: a Europe independent from the United States and Russia.”[4] In his memoirs, moreover, De Gaulle asserted that the European nations have “the same Christian origins and the same way of life, linked to one another since time immemorial by countless ties of thought, art, science, politics and trade.”[5] No wonder many Christian Democrats saw Gaullism as “a kind of Christian Democracy without Christ.”[6] European integration from shared culture to markets However, those political leaders who conceived Europe as a cultural entity were gradually disappearing. De Gasperi died already in 1954, Adenauer died in 1967, and De Gaulle resigned his presidency in 1969 and died one year later. Robert Schuman, the other famous Christian Democratic “founding father,” who has been put on the path to sainthood by Pope Francis in June 2021, died in 1963. Replacing them were younger and more pragmatic political leaders, many of whom believed that free trade was better able to bring the nations of Europe closer to each other than shared cultural roots.[7] Culture was not considered irrelevant, to be sure – this is why hardly anyone considered admitting a Muslim country like Turkey to the European Communities. But the idea of a Christian Europe whose member countries shared a distinctive heritage, which performed the important function of unifying an earlier generation of centre-right politicians, was gradually superseded by the much less concrete notion of “freedom” as a sort of telos of European integration.[8] Already in the late 1970s, powerful conservative leaders such as Helmut Kohl and Margaret Thatcher converged on the vision that European integration should secure freedom. “Freedom instead of socialism” was the CDU’s 1976 election slogan, which was quite different from “Save abendländische culture” in 1946. Socialism remained the primary enemy – but it should be fought with free markets, not Christian ethics and natural law, as Adenauer believed. Importantly, foregrounding the notion of freedom and de-emphasising thick conceptions of a shared European culture also facilitated the gradual expansion of the pan-European network of conservative parties from the mid-1970s onwards. Transnationally-minded Realpolitiker like Kohl realised already in the mid-1970s that integrating “Christian democratic and conservative traditions and parties” from non-Catholic countries into the European People’s Party and related transnational organisations was crucial to avoid political marginalisation in the constantly expanding European Communities.[9] And many new potential allies, perhaps most notably Scandinavian conservative parties who obviously had no Catholic pedigree, would have shrunk from the idea of joining a Christian Abendland modelled in the image of Charlemagne’s empire. The re-emergence of the language of Christian Europe At any rate, while the language of a Europe defined by shared culture gradually disappeared from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, decades later it re-appeared elsewhere. It was adopted by political actors who are often categorised as “right-wing populists” – more accurately, we might call them nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. These sorts of political movements have discovered and re-purposed the culturalist narrative of a “Christian Europe.” In the German-speaking world, even the notion of Abendland made a comeback on the right fringes. The Alternative für Deutschland (or AfD), Germany’s moderately successful hard-right party, commits itself in its main party manifesto to the “preservation” of “abendländisch Christian culture.”[10] The closely related anti-immigrant movement PEGIDA even has Abendland in its name: the acronym stands for “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamicisation of the Abendland.” The Austrian Freedom Party, one of the more long-standing ultraconservative nationalist parties in Europe, used the Slogan “Abendland in Christenhand,” meaning “Abendland in the hands of Christians” in the 2009 European Elections. Even more striking are the increasing appeals to the idea of Christian Europe that resound in Central and Eastern Europe. The political imaginaries of the likes of Viktor Orbán – the pugnacious Hungarian prime minister who has transformed Hungary into an “illiberal democracy” – and Jarosław Kaczyński and his Polish Law and Justice party, are defined by an understanding of Europe as a culturally Christian sphere. And they claim to preserve and defend this Europe, especially against the superficial, culturally corrosive social liberalism of the West, which they consider a major threat to its shared values and traditions. Orbán even seeks to link the notion of Christian Europe to the ideological tradition of Christian Democracy. Not only has he repeatedly called for a “Christian Democratic renaissance” that should involve a return to the values and ideas of the post-war era.[11] In February 2020, when the European People’s Party – the European alliance of Christian Democratic parties – seemed increasingly willing to expel Orbán’s party Fidesz due to the undemocratic developments in Hungary, he even drafted a three-page memorandum for the European Christian Democrats. In this memorandum, a most remarkable document for anyone interested in political ideologies, he listed all the sort of things that Christian Democrats “originally” stood for – from being “anti-communist” and “pro-subsidiarity” to being “committed representatives … of the Christian family model and the matrimony of one man and one woman.” However, he added, “We have created an impression that we are afraid to declare and openly accept who we are and what we want, as if we were afraid of losing our share of governmental authority because of ourselves.”[12] To save itself, and to save Europe, a return to the ideological roots of Christian Democracy is needed; or so Orbán argued. In sum, the language of Europe as a thick cultural community, the idea of a Christian Europe, and indeed some core elements of the ideology of Christian Democracy itself – all this has migrated to other sectors of the political spectrum and to Eastern Europe. Ideas and concepts that after WWII were part of the centre-right’s ideological repertoire are now used by nativists and ultraconservative nationalists, and used in order to justify their exclusivist Christian identity politics.[13] Note that the Eastern European parties and politicians who today reach for the narrative of Christian Europe stand for a broader backlash against the previously-hegemonic, unequivocally market-liberal and pro-Western forces that made many Western European centre-right leaders enthusiastically support Eastern Enlargement in the early 2000s. For the Polish Law and Justice party not only rejects liberal views about same sex-marriage, abortion, etc.; several of its redistributive policies also mark “a rupture with neoliberal orthodoxy,” and thus a departure from the policies of the business-friendly, pro-EU Civic Platform government of Donald Tusk, which Kaczyński’s party replaced in 2015.[14] In Orbán’s Hungary, free-market policies have largely remained in place – especially when Orbán and his cronies profited from them – yet the recent “renationalisation of the pension system [and] significantly increased spending on active labour market policies … point towards an increasing … role of the state in social protection.”[15] Understanding the migration of language One interesting interpretation of this development frames it in terms of a revolt of Eastern – and indeed Western – European nativists and nationalists against a perceived imperative to be culturally liberal and anti-nationalist. Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes perceptively note that “[t]he ultimate revenge of the Central and East European populists against Western liberalism is not merely to reject the ‘imitation imperative’, but to invert it. We are the real Europeans, Orbán and Kaczyński claim, and if the West wants to save itself, it will have to imitate the East.”[16] While there is much to be learned from this analysis, another reading of the eastward and rightward migration of culturalist understandings of Europe is available. This starts from the observation that talking about Europe as a geographical space defined by a deeply rooted common culture implies talking also about where Europe ends, where its cultural borders lie. Recall that the Europe envisaged by the Christian Democratic “founding fathers” and by De Gaulle was a much smaller, more limited entity than today’s European Union with its 27 member states. They believed, for example, that there were profound cultural differences between the abendländisch, predominantly Catholic Europe and Protestant Britain and Scandinavia. De Gaulle was in fact fervently opposed to admitting Britain to the European Communities and famously vetoed Britain’s applications to join in 1963 and 1967. If talking about Europe in cultural terms necessarily involves talking about cultural boundaries, then it is perhaps not surprising that today’s nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives came to endorse a culturalist understanding of Europe. After all, these are virtually the only political actors who indulge in talking about borders and attribute utmost importance to problematising and politicising cultural difference. Seen in this light, it is only natural that the once-innocuous notion that Europe has, as it were, “cultural borders” finds a home with them. Revisiting the question of European culture One need not endorse the political projects of Viktor Orbán, Jarosław Kaczyński and their allies to acknowledge that the questions they confront us with merit attention. What is Europe, if it is an entity defined by shared culture? And, by extension, where does Europe end? Not only those who simply do not want to leave it up to nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives to define what Europe is, culturally speaking, will need to ponder these questions. Where Europe ends is also a highly pertinent issue in current European geopolitics, and interestingly, it seems as though key EU figures are gradually converging on a position that structurally resembles a view that was prominent on the centre-right in the post-war era – without linking it to narratives about shared culture. Indeed, with the Von der Leyen Commission’s commitment to “strategic autonomy” and the objective to ascertain European sovereignty over China, the original Christian Democratic and Gaullist theme of Europe as independent “third” global power has returned with a vengeance – just that independence today means independence from the United States and China, not the United States and Soviet Russia (though Russia remains a menacing presence).[17] However, whereas De Gaulle and Christian Democratic “Gaullists” saw Europe’s Christian origins and a shared way of life as the backbone of geopolitical autonomy, the President of the Commission limits herself to mentioning the “unique single market and social market economy, a position as the world’s first trading superpower and the world’s second currency” as the sort of things that make Europe distinctive.[18] Much like earlier pragmatically-minded politicians, then, von der Leyen mostly speaks the language of markets – and of moral universalism: “We must always continue to call out human rights abuses,” she routinely insists with an eye to China.[19] But it is doubtful whether human rights talk or free market ideology are sufficient to render plausible claims to “strategic autonomy.” Being by definition boundary-insensitive and global in outlook, they are little able to furnish a convincing argument for why Europe should be more autonomous.[20] Perhaps the notion of “strategic autonomy” is actually much more about a shared European “way of life” than present EU leaders, unlike their post-war predecessors, are willing to admit. Why else would von der Leyen also want to appoint a “vice president for protecting our European way of life,” whilst describing China as “systemic rival” and even cautiously expressing uncertainty about the ally-credentials of post-Trump America? Here, the twin questions of European culture and where Europe ends, come into view again. And it seems by all means worthwhile to speak more about that – without adopting the narrow and exclusionary narratives of Orbán and Kaczyński or wishing for a return to post-war Christian Democracy or Gaullism. [1] Cited in Rosario Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland: Christian Democracy and the Idea of Europe after the Second World War’, Contemporary European History 26(2) (2017), 269. [2] Ibid. [3] Konrad Adenauer, (1946) Rede in der Aula der Universität zu Köln, 24 March 1946. Available at https://www.konrad-adenauer.de/quellen/reden/1946-03-24-uni-koeln, accessed 15 May 2020. [4] Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland’, 270. [5] Charles de Gaulle, Memoirs of Hope: Renewal and Endeavor (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971), 171. [6] Ronald J. Granieri, ‘Politics in C Minor: The CDU/CSU between Germany and Europe since the Secular Sixties’, Central European History 42(1) (2009), 18. [7] Josef Hien and Fabio Wolkenstein, ‘Where Does Europe End? Christian Democracy and the Expansion of Europe’, Journal of Common Market Studies (forthcoming). [8] Martin Steber, Die Hüter der Begriffe: Politische Sprachen des Konservativen in Großbritannien und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1945-1980 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), 410-422. [9] Wolfram Kaiser, Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 316. [10] Alternative für Deutschland, Programm für Deutschland (2016) Available at https://cdn.afd.tools/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2018/01/Programm_AfD_Druck_Online_190118.pdf, accessed 16 September 2020. [11] Cabinet Office of the Hungarian Prime Minister, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s speech at a conference held in memory of Helmut Kohl (16 June 2018), Available at: http://www.miniszterelnok.hu/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-speech-at-a-conference-held-in-memory-of-helmut-kohl/, accessed 10 June 2020. [12] Fidesz, Memorandum on the State of the European People’s Party, February 2020. [13] Olivier Roy, Is Europe Christian? (London: Hurst, 2019), 118-214. [14] Gavin Rae, ‘In the Polish Mirror’, New Left Review 124 (July/Aug 2020), 99. [15] Dorothee Bohle and Béla Greskovits, ‘Politicising embedded neoliberalism: continuity and change in Hungary’s development model’, West European Politics, 1072. [16] Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes, ‘Imitation and its Discontents’, Journal of Democracy 29(3) (2018), 127. [17] Jolyon Howorth, Europe and Biden: Towards a New Transatlantic Pact? (Brussels: Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, 2021). [18] Speech by President von der Leyen at the EU Ambassadors’ Conference 2020, 10 November 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_2064, accessed 22 June 2021. [19] Ibid. [20] As Quinn Slobodian convincingly argues, free market ideology ultimately seeks to achieve a global market with minimal governmental regulations, see Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). by Iain MacKenzie

Twenty years ago, the lines of debate between different versions of critically-oriented social and political theory were a tangled mess of misunderstandings and obfuscations. The critics of historicist metanarratives were often merged under the banner of postmodernism, grouped together in (sometimes surprising) couplings—postmodernism and poststructuralism, poststructuralism and post-Marxism, deconstruction and postmodernism—or strung together in a lazy list of these terms (and others) that usually ended with the customary ‘etc.’. Although this was partly the result of ‘posties’ still figuring out the detail of their respective challenges to and positions within modern critical thought, it was also a way of finding shelter together in a not altogether welcoming intellectual environment.

This is because it was not only the proponents of various post-isms who were unsure of what they were defending, it was also that the critics of these post-isms were indiscriminately attacking all the post-isms as one. They would cast their critical responses far and wide seeking to catch all in the nets of performative contradiction, cryptonormativism and quietism. ‘Unravelling the knots’ proposed one way of clarifying one post-ism—poststructuralism—as a small step toward inviting other posties to clarify their own position and critics to take care to avoid bycatch as they trawled the political seas.[1] That was twenty years ago: has anything changed? In many respects, yes; but not always for the better. Within the academy, taking course and module content as a rough indicator, poststructuralism has become domesticated. Once a wild and unruly animal within the house of ideas, it is now a rascally but beloved pet that we all know how to handle.[2] In political studies, this domestication has come in two ways.[3] First, it has become customary to acknowledge one’s embeddedness within regimes of power/knowledge, such that almost everyone of a critical orientation is (apparently) a Foucauldian now. Second, it has become commonplace to study discourses and how they shape identities, adding this to the methodological repertoire of political science. These two simple gestures often merit the titular rubric ‘A Poststructuralist Approach’ and yet they often remain undertheorised in the manner discussed in the original article. Often, there is neither a fully-fledged account of the emergence of structures nor an account of how meaning is constituted through the relations of difference that define linguistic and other structures. Without such in-depth accounts, we are left with empirically rich but ultimately descriptive accounts of how social forces impinge on meaning, which can have its place, or the treatment of language as a data source to be mined in search of attractive word clouds (or equivalents), which can also have its place. Whatever these claims and methods produce, however, it is not helpful to call them ‘poststructuralist’. There is still a need for the exclusive but non-deadening definition of this term, so that it is not confused with the tame house pet with which it is associated today. Part of the problem is that the discussion of how structures of meaning emerge and how they function through processes of differentiation before any dynamics of identification requires, let’s say in a Foucauldian tone, the hard work of genealogy: the patient, gray and meticulous work of the archivist combined with the lively critical work of the engaged activist.[4] But, these days, who has the patience, and the energy, for genealogy? And, in many respects, the difficulties associated with constructing intricate ‘histories of the present’ have led to a tendency to short-circuit the genealogical process (and other poststructuralist methods[5]) under the name of ‘social constructivism’. It is a shorthand, however, that has generated new entanglements, new knots, that have come to define what those of us with a long enough memory can only regret are now frequently labelled the culture wars. On one side, there are the alleged heirs of the posties, awake to the constructed nature of everything and the subtleties of all forms of oppression. On the other side, there are the new defenders of Enlightenment maturity striving to protect science from constructivism and to guard free-speech from the ‘cultural Marxists’. This epithet, of course, is the surest sign that we are in a phoney war—albeit one with real casualties—as it mimics the trawling habits of previous critics but industrialises them on a massive scale. Claims about the deleterious effects of ‘cultural Marxists’ and their social constructivist premisses simply scrape the seabed and leave it barren. But much like the debate twenty years ago, those seeking to defend ‘social constructivism’ cannot swim out of the way unless they specify that this, and other phrases like it, should never be used to end an argument. There is no use in proclaiming a social constructivism if, after all, the social itself is constructed. Shorthand is always helpful but only if we know that it is exactly that and that it will always need careful exposition and explication when critics raise the call. Moreover, what is often forgotten, in the heat of battle, is that the task is not simply to clarify one’s own claims in response to critics but to reflect upon the nature of critical exchange itself. One side of the culture wars take lively spirited debate as the signal of a flourishing marketplace of ideas. Those on the side of social construction appear to agree, simply wanting it to be a regulated marketplace of ideas. What poststructuralism brings to market is succour for neither side. Forms of critical engagement bereft of analyses of the current structures of socially mediated critical practice will always fall short of the poststructuralist project and typically dissolve into the impoverished forms of communicative exchange that never rise above the to-and-fro of opinion. It is incumbent, therefore, on poststructuralists to have a view on the nature of public interaction through social media and how these interlock with different forms of algorithmic governmentality.[6] In this way, the social constructivist shorthand can be given real critical purchase by delving deeply into the nature of public discourse and the technological forms that sustain it, particularly because these make state intervention in the name of ‘the public’ increasingly difficult (even though they can also be used, to a certain extent, for statist purposes). That said, the culture wars obfuscate a deeper misunderstanding about poststructuralism. To grasp this, however, it is important to be reminded of the overarching project of poststructuralism: it is a project aimed at completing the structuralist critique of humanism. It is important to specify this a little further. Humanism can be understood as the project of bringing meaning ‘down to earth’ so that it is in human rather than divine hands. Given this, we can articulate structuralism in a particular way: it was a series of responses to the ways in which humanism tended to treat the human being as a surreptitiously God-like entity and source of all meaning. Structuralism was the project aimed at completing the founding gesture of humanism. Poststructuralism simply recognises that there are tendencies within structuralism that similarly treat structures as analogous to God-like entities that serve as the basis of all meaning. In this respect, poststructuralism is the attempt to complete the project of structuralism, which was itself aimed at completing the project of humanism. When we understand poststructuralism in this manner it is an approach to thinking (and doing) that seeks to remove the last vestiges of enchanted, supernatural, forces, entities and explanations from all theoretical and practical activity, including science but also philosophy and the arts (broadly understood). Given this, there is no room for a pseudo-divine notion of the social that often haunts ‘social constructivism’. Indeed, given this articulation of its project, poststructuralism is hardly anti-science (as some in the culture wars might claim); rather, it is a project of understanding meaning in every respect without reinstating a source of meaning that stands ‘outside’ or ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the world that we inhabit. In fact, poststructuralists (though not all posties) are rather fond of science and they certainly do not want to undermine the natural sciences in the name of lazy ‘social constructivism’. It is, in fact, a way of seeking better science with help of philosophy, and a way of seeking better philosophy with the help of science (and for the full sense of what’s at stake, this gesture should be triangulated through inclusion of the arts). But how can there be a ‘better’ if the posties, including the poststructuralists, are sceptical of metanarratives? This question brings us to one of the more fruitful aspects that has changed in the last twenty years. The most interesting challenge faced by poststructuralists in recent times has come from the emergence of forms of neo-rationalism looking to reinvigorate critical philosophy through pragmatically oriented forms of Kantianism and non-totalising forms of Hegelianism.[7] From the neo-rationalist perspective, poststructuralism has failed in its attempts to naturalise meaning, to take it away from explanations that rely upon supernatural forces, to the extent that it is reliant upon a transcendent notion of Life that treats the priority of becoming over being as given. This immanent critique of poststructuralism cuts much closer to the bone than the Critical Theory inspired fishing which cast their nets wide but always from the harbour of their own shores. At the heart of this dispute is whether or not what we know about the world and how we know what we know about the world can be articulated within a single theoretical framework. For the neo-rationalist, it is (in principle, at least) possible to work on the assumption that there is an underlying unity between ontology and epistemology founded upon a specific conception of reason-giving. For poststructuralists, exploration of the conditions of experience suggests a dynamic distance between the what and the how, such that the task is to secure the claims of philosophy, art and science as equal routes into our understanding of both. While this reconstitutes a certain return to the pre-critical debates between rationalists and empiricists, it is equally indebted to the critical turn with respect to the shared task of legitimating knowledge claims, but with a pragmatic or practical twist. Both the neo-rationalists and the poststructuralists pragmatically assess the worth of the knowledge produced by virtue of the challenges they proffer to arguments that rely upon a transcendent God-like entity and the dominant form of this today; namely, the sense of self-identity that underpins capitalist endeavours to maximise profit. This critical perspective, perhaps surprisingly, was seeded within the fertile soil of American pragmatism. For the pragmatists—and we might think especially of Pierce, Sellars, and Dewey—it is the practical application of philosophy that engenders standards of truth, rightness and value. Admittedly, in the hands of its founding fathers, this practical application was often guided by the idea of maintaining the status quo. But that is not essential. Neo-rationalists and poststructuralists have found a shared concern with the idea that philosophical practice should be guided by the critique of capitalist forms of thought and life. As such, they share a common ground upon which meaningful discussion can be forged, aside from the culture wars (which are simply a reflex of capitalist identitarian thinking). While deep-seated divisions remain—does the knowledge generated by social practices of reason giving trump the experience of creative learning or are they on the same cognitive footing?—the shared sense of seeking a critical but non-final standard for what counts as better (better than the identity-oriented thinking sustaining capitalism) is driving much of the most productive debate and discussion at the present time. Work of this kind reminds us that poststructuralism is still a wild animal rather than a domesticated house pet, that it is a critical project but also one that has political intent. That said, it is not always easy to convey the political dimension of poststructuralism, especially given the vexed question of its relationship to ideology. As discussed in the original article, part of the initial excitement about poststructuralism was that its major figures distanced themselves from the idea of ideology critique. However, this was only ever the beginning of a complex story about the relationship of poststructuralism to ideology and never the end.[8] While Marxist notions of ideology were critiqued for the ways in which they incorporated notions of the transcendental subject, naïve versions of what counts as real and over-inflated notions of truth, poststructuralists have always endorsed the power of individual subjects to express complex notions of reality and historically sensitive and effective notions of truth, and to do so against dominant social and political formations. These formations are often given unusual names—dispositif, assemblages, discourses, and such like—but the aim of unsettling and ultimately unseating the dogmatic images and frozen practices of social and political life is not too distant from that animating Marxism. Of course, as Deleuze and Guattari expressed it, any revised Marxism needs to be informed by significant doses of Nietzscheanism and Freudianism (just as these need large doses of Marxism if they are to avoid becoming critically quietest and practically relevant for the critique of capitalism).[9] What results, though, is an immanent version of ideology critique rather than a rejection of it tout court: there are many assemblages/ideologies that dominate our thoughts, feelings and behaviour and it is possible to learn how they operate by making a difference to how they function and reproduce themselves. In searching for the natural bases of meaningful worlds it is no surprise that poststructuralists have become adept at diagnoses of how natural processes can lead to systems of meaning that import supernatural fetishes into our everyday lives, and how these are sustained in ways even beyond merely serving the interests of the economically powerful. There appear to be an endless number of these knots that need untying. If we want to untie at least some of them, then unravelling the knots that currently have poststructuralism tangled up in a phoney culture war is another small step on the road to bringing a meaningful life fully down to earth. [1] I.MacKenzie, ‘Unravelling the knots: post-structuralism and other “post-isms”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 6 (3), 2001, pp. 331–45. [2] I. MacKenzie and R. Porter, ‘Drama out of a crisis? Poststructuralism and the Politics of Everyday Life’, Political Studies Review, 15 (4), 2017, pp. 528–38. [3] One of the interesting features of the recent history of poststructuralism is that it is not the same across disciplines. Of course, this need for disciplinary specificity with respect to how knowledge is disrupted, new forms of knowledge established and then domesticated is part of what poststructuralism offers. That said, much of what follows can be read across various disciplines in the arts, humanities, sciences and social sciences to the extent that the legacies of humanism and historicism traverse these disciplines. [4] M. Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in D. Bouchard (ed.) Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault (New York: Cornell University Press, 1992 [1971]), pp. 139–64. [5] B. Dillet, I. MacKenzie and R. Porter (eds) The Edinburgh Companion to Poststructuralism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013). [6] A. Rouvroy, ‘The End(s) of Critique: data-behaviourism vs due-process’ in M. Hildebrandt and E. De Vries (eds), Privacy, Due Process and the Computational Turn. Philosophers of Law Meet Philosophers of Technology (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 143–68. [7] See R. Brassier’s engagment with the work of Wilfrid Sellars, for example: 'Nominalism, Naturalism, and Materialism: Sellars' Critical Ontology' in B. Bashour and H. Muller (eds) Contemporary Philosophical Naturalism and its Implications (Routledge: London, 2013). [8] R. Porter, Ideology: Contemporary Social, Political and Cultural Theory (Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2006) and S. Malešević and I. MacKenzie (eds), Ideology After Poststructuralism (Oxford: Pluto Press, 2002). [9] G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (New York: Viking Press, 1977). This triangulation of the philosophers of suspicion, with a view to completing the Kantian project of critique, is one especially insightful way of reading this provocative text: see E. Holland, Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis (London: Routledge, 2002). by Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien

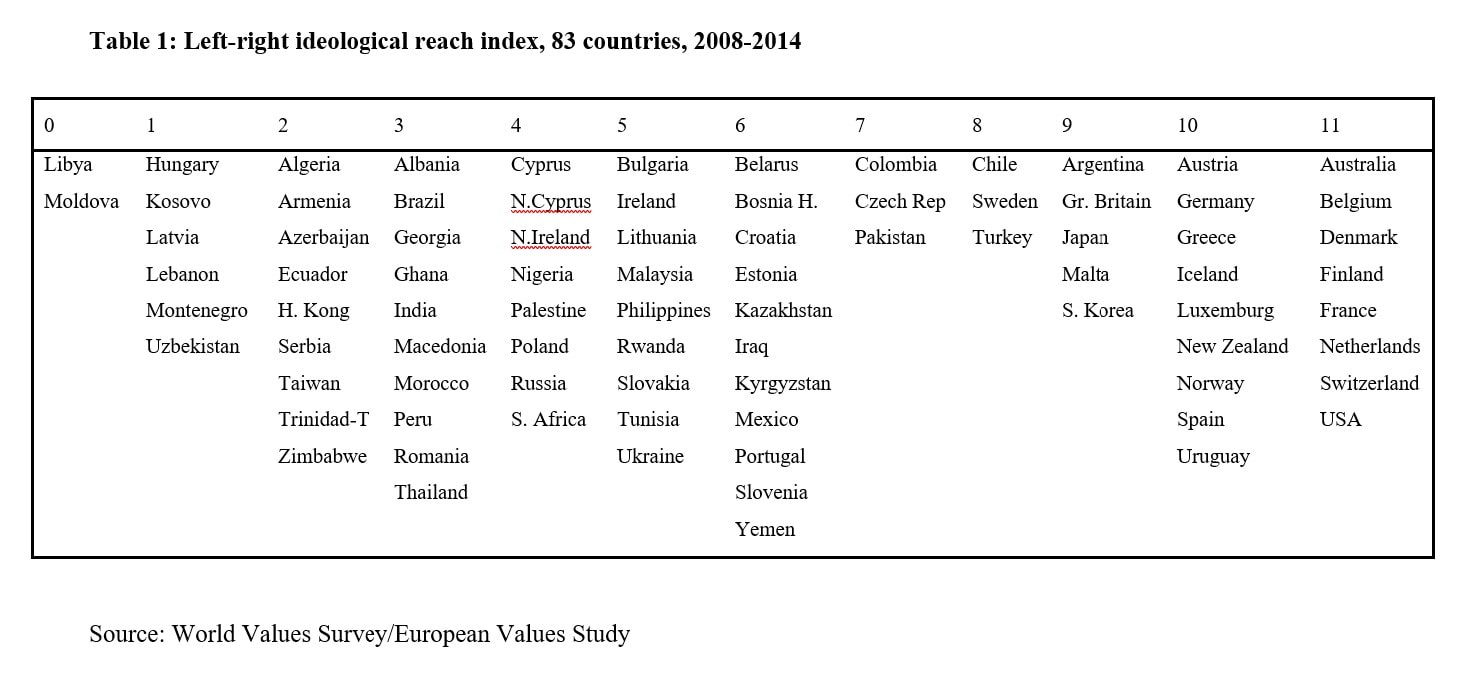

In recent years, several analysts have contended that the old cleavage between left and right has faded gradually, to become less central politically than it once was. The end of communism, the unchallenged victory of market capitalism, and the rise of neoliberalism narrowed the distance between parties of the left and of the right, and reduced the range of options available in political debates. Yet, although the left-right distinction may have become blunter as a cognitive instrument for politicians and voters, numerous studies show that it has not been replaced. In fact, no ideological cleavage is more encompassing and ubiquitous than the opposition between the left and the right.[1] When asked, most people across the world are able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, which basically divides those who support or oppose social change in the direction of greater equality. Ideological self-positioning also tends to be in line with the values and policy preferences associated with one of the two sides. The strength of this left-right schema, however, varies significantly among countries. In some cases, left-right positions correlate strongly with expected attitudes about equality, the state, the market, or social diversity; in others, they do not. We know little about the factors that make the left-right opposition more or less effective in structuring national debates. At best, existing studies suggest that left-right ideology is a more powerful constraint in Western democracies than elsewhere. To assess this question, we have taken the measure of cross-national variations in left-right ideology in 83 societies, and linked them to various factors, including economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy. Instead of focusing on individual determinants of ideology such as social class, gender or education, as scholars generally do, our analysis looks at country-level survey evidence and evaluates how, in each country, political debates are framed, or not framed, in left-right terms. The idea, along the lines suggested by Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, is to take the mass attitudes measured by large-N comparative survey projects as “stable attributes of given societies,” and as indicative of a country’s elites’ success in structuring politics along left-right dimensions. More specifically, we consider answers to twelve survey questions that capture the standard dimensions of the left-right political distinction. All answers were collected between 2008 and 2014 through the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS). The twelve questions include, for each society, one on individual left-right self-positioning, and eleven related to issues that have historically divided the two sides. The varying degree of ideological consistency in citizens’ responses then makes it possible to assess the architecture of a country's political debates and make cross-national comparisons. This approach to the workings of left-right ideology has two advantages. First, it moves the discussion of ideology beyond Western countries, and makes it possible to draw an extensive map of national ideological patterns. Second, and more importantly, because we use aggregate survey evidence, we can assess national-level causal mechanisms, and weigh, in particular, the respective influence of economic, social, and political factors on the constitution of the left-right cleavage. Our results indicate that the left-right opposition is unevenly effective in structuring national politics. Individual answers to questions about equality, personal responsibility, homosexuality, the army, churches, or major companies correlate with left-right self-positioning in more than half of the countries considered. But answers to questions about abortion, government ownership of industry, competition, trade unions, or environmental groups correlate with ideological self-positioning in only a third of the cases. In line with the expectations of Inglehart and Welzel, we also find that economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy are the best predictors of a structured left-right debate. Theorising left and right The construction of ideological identities is both a top-down and a bottom-up process, whereby people adopt political orientations defined by elites and institutions in line with their own personal predispositions. Psychologists have naturally paid more attention to the bottom-up, personal determinants of ideology, while political scientists have been more interested in the top-down, collective process. As a top-down process, the building of the left-right divide hinges on a country’s elites’ and institutions’ capacity to propose to voters what Paul Sniderman and John Bullock call a “menu of choices.” For these authors, political institutions—most notably parties—give consistency to the views of ordinary citizens, by providing coherent menus from which they can choose. As left-right self-positioning is strongly correlated with partisanship, we can hypothesise that a long-established, institutionalised party system contributes to structure ideological debates along left-right lines, compared to the more volatile politics of countries with fragile democracies. To evaluate if the “menu of choices” proposed by a country’s elites and parties and adopted by voters is organised along left and right lanes, we test whether divisions in a country’s public opinion appear consistent with individual left-right self-positioning. People on the left are likely to be more favourable to equality, state intervention, public ownership, and trade unions, and people on the right better disposed toward markets, individual incentives, competition, and major companies. The left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion and more supportive of environmental organisations, and the right more at ease with churches and the armed forces. In countries where the menu of choices is strongly structured by the left-right opposition, there should be significant relationships between individual left-right self-positioning and the expected attitudes on these questions; in countries with a less powerful left-right schema, these relationships should be weaker. Moreover, one should expect a connection between the structure of left-right discourse and the human development sequence identified by Inglehart and Welzel. Economic development, secularisation, and democratisation broaden the possibility, the willingness, and the rights of people to consider social alternatives. Economic development fosters the material capacity of a people to make choices, secularisation expands the moral frontiers of available choices, and democratic consolidation allows political parties and groups to define over time a menu of choices ordered around the usual left-right patterns. Left-right patterns should thus be associated with these three dimensions of human development. Methodology 83 societies have a complete set of WVS/EVS answers for the questions we select. The core question of interest concerns left-right self-positioning, and it is addressed by asking respondents to locate themselves on a 1 to 10 scale going from left to right. Although the rate of response varies significantly across countries, overall, about three-quarter of respondents proved able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, allowing for valid inferences about ideology. To verify whether this left-right positioning corresponds to consistent ideological stances, we correlate left-right positioning to responses on substantive political issues. Some of our eleven ideological questions refer to the core socio-economic components of the left-right cleavage (attitudes about equality, private or public ownership, the role of government, or competition), others concern cultural or social values (attitudes about homosexuality and abortion), and others tap respondents’ views about various organisations (churches, the armed forces, labor unions, major companies, and environmental organisations). We expect people on the left to be more favourable to equal incomes, public ownership of business or industry, and the government’s responsibility “to ensure that everyone is provided for,” and less likely to consider that “competition is good.” Respondents on the left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion, and more confident in labour unions and environmental organisations, but less so in the churches, the armed forces, and major companies. Using national responses to our eleven questions on substantive issues, we build a composite dependent variable, called left-right ideological reach. This variable measures the extent to which, in a given country, left-right self-positioning predicts the expected ideological stances on substantive political issues. If, in country A, the relationship between self-positioning and, say, attitudes about equality is significant (p < 0.05) and in the expected direction, we give a score of 1, and if not of 0. Adding results for eleven questions, a country’s score for left-right ideological reach can then range from 0, when self-positioning never correlates in the expected direction with a substantive left-right political division, to 11, when the expected relationships are present for all questions. To account for national differences in ideological reach, we use indicators for economic development, secularisation, and democratic experience, as well as a number of control variables, for cultural differences in particular. Results Left-right ideological reach varies significantly across countries, from 0 for Libya and Moldova to 11 for a number of Western countries, including France and the United States. As Table 1 shows, there are 27 countries with scores of 0 to 3, where left-right self-positioning hardly predicts respondents’ positions on traditional issues dividing the left and the right; 31 where left-right ideological reach is moderate, with scores of 4 to 7; and 25 where a person’s ideological self-positioning predicts her position on most issues, most of the time, with scores of 8 to 11. This is a new, multidimensional, and country-scale representation of left and right public attitudes across the world, and the idea of a relationship between left-right self-positioning and substantive political orientations appears validated, at least for nearly two thirds of our sample.

A cursory look at the data suggests, in line with the literature and with our theory, that left-right ideological reach is influenced by economic and democratic development. Countries with high scores in Table 1 are predominantly rich, established democracies; countries at the low end of the scale tend to be poorer, with authoritarian regimes or newer democracies. Indeed, economic development, measured by GDP per capita, is strongly correlated with ideological reach, and so are our indicators of secularisation and democracy. In multiple regressions, the three explanatory variables considered are significant, with democracy coming first. Control variables for cultural differences (religiosity and civilisations) are non-significant. These results are consistent with our interpretation of the left-right divide as a political construct that has global resonance but is clearly more structured in countries that have long experienced economic development, secularisation, and democratic politics. They also dispose of the seemingly common sense but misleading argument that would jump from a look at the cases in Table 1 to the conclusion that left and right are a Western specificity. Looking closely at the same table, one can see countries like Uruguay, Argentina, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Pakistan with scores of 7 or more, and countries like Hungary, Taiwan, and Brazil with low scores. Fostered by economic development and to some extent by secularisation, the left-right cleavage remains, first and foremost, a product of the enduring democratic conflict for control of the government. Not surprisingly, a host of comparative politics writings lend support to this conclusion, and suggests that the left-right divide is more structuring in countries with a strongly institutionalised party system. Conclusion The evidence from cross-national surveys is rather clear: around the world, most people are able and willing to locate themselves on a left-right scale and when they do, they tend to understand what this self-positioning implies. Their understanding, however, tends to be more comprehensive in countries that are more advanced economically, more secular, and more solidly democratic. As political parties compete for the popular vote, they construct an ideological pattern that makes sense for both elites and voters, and that gives structure to politics. When they fail to do so, or when democracy is non-existent, political discourse remains more haphazard, driven by context and personalities. To go beyond these conclusions, we would need to probe further the political mechanisms that contribute to the development of ideology. Looking systematically at the party system institutionalisation hypothesis, in particular, would seem promising. For now, however, we can be satisfied that the language of the left and the right seems to function as an imperfect but critical unifying element in global politics. [1] Russell J. Dalton, ‘Social Modernization and the End of Ideology Debate: Patterns of Ideological Polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7:1 (2006), pp. 1-22; John T. Jost, ‘The End of the End of Ideology’, American Psychologist, 61:7 (2006), pp. 651-670; Peter Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 206-222; Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien, Left and Right in Global Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); André Freire and Kats Kivistik, ‘Western and Non-Western Meanings of the Left-Right Divide across Four Continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18:2 (2013), pp. 171-199. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed