|

4/10/2021 Jean Grave, the First World War, and the memorialisation of anarchism: An interview with Constance Bantman, part 2Read Now by John-Erik Hansson

John-Erik Hansson: Let us now talk about the French and European contexts and turn to the First World War and to the relationship between anarchism and the French Third Republic. You discuss at length Jean Grave’s u-turn regarding the war and what leads him to draft and sign the Manifesto of the Sixteen, condemning him to oblivion, because he was one of the apostates—although other signatories like Kropotkin managed to remain in the good graces of a lot of people in the anarchist movement. There's an ongoing revision of our understanding of what exactly led to the split in the anarchist movement between the defencists, who were in favour of participating in the war, and those who simply opposed the First World War, exemplified by the recent edited collection Anarchism 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War.[1] For a long time being defencism was considered to be a betrayal of anarchist principles, but that view has changed over the last couple of years. What was Grave’s role in this debate? How does studying Grave help us rethink anarchism at that historical juncture?

Constance Bantman: The first thing to say is that the revision is very much an academic thing; that’s important to highlight when you talk about anarchism, which is of course a social movement with a very strong historical culture. The war will come up when you're talking to the activists who really know their history when you mention Grave. On France’s leading anarchist radio channel, Radio Libertaire, a few years ago, I heard him called a “social traître” [traitor to the cause]—I couldn't believe it! But within academic circles, the revision is underway and a great deal has come out: the volume that you mentioned and Ruth Kinna’s work on Kropotkin as well, all of which have been very important to revising this history. That’s courageous work as well, given all we’ve said about the enduringly sensitive nature of this discussion. Concerning Grave’s role in this, the first aspect to consider is the importance of daily interactions in people's lives. That’s an angle you get from a biography. So much has been said about Kropotkin’s own story and intellectual positions, and how this informed his stance during the war. Of course, that doesn't explain everything, especially if you look to the opponents to the war. Grave was initially really opposed to the war, his transition was really gradual but it was a U-turn, connected to his friendship with Kropotkin, who told him off quite fiercely for being opposed to the war. One thing we do see through Grave is this sense that some anarchists clearly predicted what would later be known revanchisme, the idea that there was so much militarism in French society that when the Entente won the war, there would be really brutal terms imposed on Germany, which would lead to another war. That’s something that Peter Ryley has written about in Anarchism 1914-18. Some anarchists were pretty lucid actually in their analysis and you do found traces of that in Grave. He really clearly understood the depth of the militarism of French society, and that's when he did a bit of a U-turn. He was also in Britain at the time, and didn't quite realise how difficult the situation was. He had left Les Temps Nouveaux and the paper was looked after by colleagues. They were receiving lots of letters from the front, from soldiers and, as has been analysed by other historians, this was crucial in the growth of an anti-war sentiment for them. They could see directly the horrors happening in the trenches, whereas Grave was immersed in upper-class British circles and had no clear sense of the brutality of the war. So, again, it's a mixture of ideas, ideology, and the contingencies of personal and activist lives when you try to assess positions that such complicated times. JEH: Again, this highlights the importance of personal connections in the formulation of political and ideological positions. While these positions might be influenced by personal connections, they then become rationalised into arguments that become part of the ideological vocabulary and the ideological fault lines in the movement itself… and that leads to the Manifesto of the Sixteen, in a sense. CB: Yes, absolutely that's very true. The manifesto was written as a document published initially in the press; it was not a placard. Arguments in favour of defencism as well as arguments by anti-war groups were published in the press in the form of letters meant to influence people. Grave once referred to the Manifesto of the Sixteen as the manifesto he wrote in 1917, whereas it had actually been written in 1916. This just shows that what is now regarded as this landmark document, this watershed moment in the history of Western anarchism was, for Grave, just one of the many articles that he had written. I think it took some time, maybe a decade or two, you can see that through Grave, for the Manifesto to be consolidated into the historical monument that it now is. Looking at this period through Grave brings out a degree of fluidity which is otherwise not apparent. JEH: This is very interesting point. In a way, anarchists built their own historical narrative and created a landmark out of something that was, as you mentioned, initially just another set of arguments between people who are connected and often knew one another personally. But this particular argument became much more important because of the way in which the anarchist movement memorialised itself. CB: Yes, absolutely and I think tracing it would be interested to trace how national historiographies and activist memories sort of converge to establish versions of history. In France, I would be really interested to see when exactly the Manifesto of the Sixteen congealed into this historic landmark. I wonder if it's Maitron and a mixture of activist circles and discussions. I haven't studied so much the period around the Second World War, but really, with activist memories in this period we may have a missing link here to understand the formation and how the 19th century was memorialised. JEH: From the First World War to the Third Republic, I would like to relate your book to a recent article by Danny Evans.[2] Evans argues that anarchism could or should be seen as “the movement and imaginary that opposed the national integration of working classes”. Grave is interesting in this respect because he becomes domesticated by the Third Republic. Would you say that anarchism and French republicanism are in a kind of dialectical relationship from 1870 until the Second World War, moving from hard-hitting repression to the domestication of a certain strand of anarchism seen as respectable or acceptable by French republicanism? CB: Now that's a very good point, and an important contribution by Danny Evans. Grave always had these links with progressive Republican figures and organisations like the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, Freethinkers, academics etc.… One of his assets as well among his networks is his ability to get on with people, to mobilise them, for instance, in protest again repression in Spain and the Hispanic world. Many progressive figures were involved in that. And when Grave himself fell foul of the law during the highly repressive episode of 1892–94, many Republicans supported him, which suggests that a degree of republican integration was always latent for Grave. Then the war happened and he picked the right side from the Republicans’ perspective, and by then you're right, domestication is indeed a good term. I would also add that many of these Republicans considered that anarchism had been an important episode in the history of the young Third Republic, which might have made more favourably inclined towards it. Now if we look at domestication, Grave is an example of a sort of willing domestication, as you might say that perhaps he does age into conservative anarchism. But a classic example is that of Louise Michel. Sidonie Verhaeghe has just written a really interesting book about this[3], because if you think about Louise Michel having her entry into the Pantheon being discussed in recent years, she would be absolutely horrified at the suggestion. Having a square named after her at the foot of the Sacré Coeur, that’s almost trolling! But anarchism really reflects the history of the Third Republic from the early days, when the Republic was very unstable. You had the Boulangiste episode, and anarchism was perceived to be such a threat initially, until the strand represented by Grave ceases to be seen in that way. After the war, we enter the phase of memorialisation and reinterpretation; Michel and Grave represent two slightly different facets of that process. Regarding the point about the integration of the working classes, the flip side of Danny’s argument has often been used by historians—I'm thinking about Wayne Thorpe,[4] in particular—to explain why everything fell apart for French anarchists at the start of the First World War. The war just revealed how integrated the French working classes were, beyond the rhetoric of defiance they displayed. It's an argument you find to explain the lack of numerical strength of the CGT too. The working classes had integrated and the Republic had taken root, and Thorpe explains what happens with the First World War in the anarchist and syndicalist movements across Europe by looking at the prism of integration. That's a very fruitful way of looking at it. That's also great explanation because it encompasses so many different factors—economics, political control, and the rise of the big socialist parties which was of course crucial at the time. JEH: Actually, I was also thinking of the historical memory of socialists, as mass party socialism becomes dominant in the 20th century. In the late 19th century in the early 20th century when socialism was formulated, anarchism was an important part of that broad ideological conversation. But by the end of the First World War, from the socialists’ perspective, that debate is over. The socialists have won the ideological battle, and they are able to mobilise in a way that the anarchists aren't able to anymore. And at that point, the socialists can look back and try to bring anarchists into the fold, paying a form of respect to anarchism as an important part of socialist history. CB: Yes, I think there is probably an element of that, perhaps even an element of nostalgia. Many of these socialist leaders had dabbled with anarchism themselves before the war, so there is this dimension of personal experience and sometimes affinity. And it was still fairly recent history for them, I suppose, which plays out in a number of ways. There’s also the question of what happens with revolutionary ideas—for us the revolution is a fairly distant event, but for them the Commune was not such a distant memory. So, there is also this question of what do you do with a genuine revolutionary movement, like anarchism, and I think it was probably something they had to consider. [1] Ruth Kinna and Matthew S. Adams, eds., Anarchism, 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020); see also Matthew S. Adams, “Anarchism and the First World War,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, ed. Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_23. [2] https://abcwithdannyandjim.substack.com/p/anarchism-as-non-integration [3] Sidonie Verhaeghe, Vive Louise Michel! Célébrité et postérité d’une figure anarchiste (Vulaines sur Seine: Editions du Croquant, 2021). [4] Wayne Thorpe, “The European Syndicalists and the War, 1914-1918”, Contemporary European History 10(1) (2001), 1–24; J.-J. Becker and A. Kriegel, 1914: La Guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français (Paris: Armand Colin, 1964). 27/9/2021 Jean Grave, print culture, and the networks of anarchist transnationalism: An interview with Constance BantmanRead Now by John-Erik Hansson

John-Erik Hansson: Let's start with a few introductory questions. Very broadly, who Jean Grave and why should we study him? What does he stand for? Does the book present a general case for studying minor figures in the history of anarchism, as Jean Grave is no longer necessarily so well known?

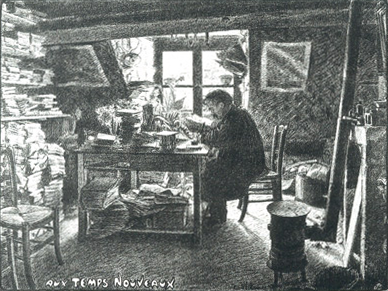

Constance Bantman: Jean Grave was a French anarchist—he was really quite famous until his death in 1939. He was mainly known as the editor of three highly influential anarchist periodicals. First of all, Le Révolté, which was set up in 1879 in Geneva by Peter Kropotkin and a few others, chiefly Elisée Reclus. It was handed over to Grave around the 1883 and he kept it going until 1885, when the paper was relocated to Paris. It was eventually discontinued and relaunched in 1887 as La Révolte, which was forced to close in 1894, in times of really intense anarchist persecution in France. It was relaunched again in 1895 as Les Temps Nouveaux, which more or less ceased business in 1914 when the war started. Grave was also involved in several other publications post-war and until his death. So Grave is primarily known for being a newspaper editor, one might say one of the most influential editors in the global anarchist movement. And he was really quite well known at the time, and was also a theorist in his own right. That's one aspect of his work that completely sank into oblivion. I think you'd really struggle to find anyone reading Grave nowadays. There might be somebody popping up on social media every now and then, but that's about it! But at the time, he was a really influential theorist of anarchism, not quite on par with Kropotkin or say Malatesta or Reclus, but people did read him. His work was translated into numerous languages and published in multiple editions. He was a theorist of anarchist communism very broadly speaking. He was interested in education, and educationalism. It's hard to assess the specificity of his work, really. I would say educationalism within the broader anarchist communist framework was important. He was quite critical of syndicalism, and he was, as we’ll discuss later, pro Entente during the war. He is worth studying not only because he was influential person, but also because of his remarkably long career in anarchism. He became a politicised at the time of the Paris Commune, when he was a teenager. I think his father was quite political and the young Grave was distantly involved in the commune—he was 17 at the time. By the late 1870s, he was politically active, and he never stopped until his death. His long political career mirrors the history of French and international anarchism, and the place of anarchism within the French Third Republic. Grave wrote his autobiography with the title Quarante Ans de Propagande Anarchiste [Forty Years of Anarchist Propaganda], and when I wrote the book, I was thinking, “maybe I could call it Seventy Years of Anarchist Propaganda?”, because that's more accurate. Grave was being quite humble. Concerning your question about the relevance of studying minor figures, I think there is something interesting in resurrecting figures who have fallen from grace—Grave especially because of his position during World War One. But I think Grave was an intermediary, not quite a minor figure, because he was so well known and the time. These intermediaries, who were really close to highly influential historical figures, allow us to get new historical insights into figures like a Kropotkin, who was a really close friend of his, or Reclus, with whom he sparred quite a lot. They also allow us to piece back together the social history of anarchism, to shed light on the history of ideas in many different ways, and to reflect on more canonical history as well. JEH: Your book is a biography of Grave but it's also a biography of his periodicals, especially La Révolte and Les Temps Nouveaux. What led you to that focus? What brought you to take that angle on Grave and on anarchism more generally? CB: That's also related to your first question—which was “why study Grave?”. One of the main drivers of my study was a reflection on the concept of anarchist transnationalism, which I’ve been interested in for a long time, like many historians have. My work to date was focused on exile and I was absolutely fascinated with Grave who pretty much never left Paris at a time of intense anarchist forced mobility. Lots of French anarchists went into exile and there was a great deal of labour migration. But Grave was pretty much always in Paris, and yet, he was everywhere. If syndicalism was being discussed in Latin America, you could be sure that Grave would be part of that conversation. Same in Japan, same in discussions of political violence in the UK, where there were many French anarchists. What I realised is that Grave presents us with what we might call an example of immobile or rooted transnationalism and the fact that it was absolutely fine or feasible for somebody to be sedentary and to stay in Paris whilst having global influence. The reason for this, what solves the problem, is print culture and the mobility of print in this period. So that's how I came to be interested in the papers, because they were agents of circulation of mobility. As Pierre-Yves Saunier, an influential historian of transnationalism, wrote, for the international circulation of ideas to happen, you don't necessarily need personal mobility, you need connectors. The papers were the great connectors. In addition to that, the papers are absolutely fascinating. They are remarkable cultural documents, because one of Grave’s salient features was that he was connected with so many writers and visual artists. He was really adept at enlisting the support for the movement, and the papers really reflect that. The papers had a supplément littéraire, which was sometimes illustrated and many illustrations were sold for charity purposes, alongside the paper, by artists who are nowadays extremely famous for some of them (for instance Grave’s friend Paul Signac), or by illustrators. So there was this really lush visual and literary culture associated with the papers, which was just pleasant to study as well. JEH: This is a great segue into the next set of questions. You’ve emphasised the importance of print culture throughout the book and in your answers up to now. So, how would you characterise the relationship between anarchism and print culture in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries? CB: Well, I’ve thought about this a lot, and I think I would use the term symbiotic. I think it was a very symbiotic relationship, they fed off and into each other. There are many ways in which this imbrication of anarchism with print culture functioned. A few examples: print culture existed through periodicals, in particular, but also pamphlets which were sold and printed separately. All of these were the sites where anarchist ideology was elaborated and constructed dialogically. These publications were fora, there was a great deal of discussions within and around the papers and other publications. Print culture was the prime place of ideological elaboration. It was also the key place for the dissemination of ideology. We've discussed illustrations—and Grave’s papers were famously very dry, very theoretical—but if we think of papers like the Père Peinard, a really engaging contemporary publication, there was a language, there was also a visual style, which was incredibly effective in conveying very complex, occasionally dry ideas to their target audiences. So that's another aspect in this relationship between anarchism and print culture. Because, precisely, there was no party framework, the press was the main forum. Another aspect is also that the press and owning anarchist print was regarded by the authorities as the ultimate sign of anarchist belonging. This was very much acknowledged that the time, and this was a way of self-identification as well. The historian Jean Maitron has written extensively about anarchist being a very bookish culture in this respect, and this notion of print ownership as a sign of anarchist belonging is striking when you look at police records. This idea that owning and reading anarchist material was a sign of being an anarchist is really important. Print culture had other functions as well. For instance, I've mentioned the global influence of Grave, it was also through the press that anarchism was developed as a global movement. The press also facilitated the daily organisation of anarchist circles, connecting activists with one another. So, there are so many practical, organisational, ideological and cultural ways in which print culture made anarchism possible. In return, anarchism fostered this absolutely remarkable print culture, which is one of our main sources today in documenting the history of the movement. JEH: When I was reading the book, I was fascinated by the discussion of the formation of an anarchist identity alongside that of an anarchist ideology. I was wondering if you could comment, a little bit about the kind of dynamics of the relationship between the formation of an anarchist identity and at the same time, the formation of an anarchist ideology. CB: Yes, I think that's such an interesting approach, because at the moment the great buzzword among historians of anarchism is “communities”, which makes me think that this notion of anarchist identity is somewhat under-explored. Paradoxically, we tend to think about anarchist identity through the collective prism of community and they’re not quite the same thing. Of course, the biography is a good entry way into these questions. Grave was somebody who was interested in ideas, but being an anarchist was a praxis as well. It was about taking part in gatherings in ‘Cercles’ or local groups, it was very much a sociability; it fed on this social identity and that's how it developed in the aftermath of the Second Industrial Revolution. Grave’s own itinerary shows that anarchism was very much a place where new identities, individual and collective, were created. It's been a matter of debate, to what extent anarchists actually identified with the ideology or recognised it, or were well versed in it. For many people, it was more practical—if we think about the many sorts of petty criminals that the police identified as anarchist were probably not particularly familiar with Kropotkin’s ideas or say Stirner’s, but to somebody like Grave, Kropotkin—and more generally, ideas and theories—were, of course, very important. JEH: To continue at the intersection of identity and ideology, bringing print culture back in, one of the things that struck me when I was reading your book is how you show the way in which different editors of anarchist papers interacted with and responded to one another. There is this debate between Jean Grave and Benjamin Tucker taking place throughout the pages of Liberty and La Révolte—mirroring the broader debate between anarchist individualists and anarchist communists. Yet, they maintained a veneer of unity as anarchists and actively sought to continue collaborating. This seems to have been common, especially before 1900, but it that changes over time, and you are able to track the subsequent process of ideological reconfiguration and division. So, I was wondering, firstly, what you thought this could tell us about anarchism at the time, and secondly, why you think things changed in the early 20th century. CB: It's a striking story to follow. What we can see with anarchism, in particular through periodicals in the 1880s, is the case of an ideology emerging and constituting itself as a social movement. There is a sense of shared identity and affinities between, say Tucker and Grave—occasionally there are bitter fallouts, but still the sense of commonality of interests, for instance in the face of repression, is quite important. In the late 1890s, post ‘propaganda by the deed’, it's quite established that there is a transition, which Jean Maitron has called “la dispersion des tendances” [the scattering of tendencies]. We can see that things become a bit more ideologically polarised especially, I think, because of the advent of new brands of anarchist individualism and lifestyle experiments which more conservative anarchists like Grave were horrified by. Vegetarianism, women's emancipation, free love colonies—all that was an absolute nightmare for them. And then you have les gueulards [the loudmouths] of La Guerre Sociale who also have a lot of misgivings and hostility towards figures, especially like Grave, who claim to have so much power and ascendancy in the movement. At this stage, it becomes quite fixed and this feeling of unity dissolves. Then the war exposes deep ideological rifts. I’ve never quite thought of it in those terms, but it’s also absolutely striking to see such a condensed history of a highly influential social movement from emergence, unity, to the shattering blows of the First World War. JEH: And in this way, I think what you show in the book is how periodicals help us track and reflect on these processes of ideological formation ideological differentiation which take place in a very short amount of time. Anarchism, then, can be seen as a microcosm for the study of ideological differentiation more broadly. CB: Absolutely, that is really interesting. There’d have to be a comparative study to really identify the specificities of anarchist print culture. In the case of anarchism, the main ideological debates play out in major periodicals. The doctrine of syndicalism was elaborated, if you look at Europe, in the dialogue between a number of publications: Freedom in London, Le Père Peinard and then La Sociale when Pouget comes back to Paris, La Révolte, Les Temps Nouveaux, the Italian publications coming out in London, Italy, and the US at the same time. These debates and discussions unfold the big theoretical pieces as well as pamphlets, but what is also interesting is how it plays out in the paratextual elements of the periodicals—in one footnote you might find a commentary, or the report of a meeting where these questions were also being discussed I find that one of the joys of studying that press is how they argue with each other. Conflicts between Grave and, say, Émile Armand (L’Anarchie) were such that they could be really vile with each other, and it could go on for weeks—the squabbling and the pettiness and “you said that…” and “the spy in London was doing this…”, all of which might be echoed by placards and manifestoes… These are arguments reflected in various elements of print culture to which we might not necessarily pay attention, but which were really important in this process of differentiation. JEH: Thinking about another dimension of anarchism and thinking about Grave’s practice as an editor and publisher. In anarchism it's common to say that prefiguration, prefigurative politics are central. Anarchists want to enact the kinds of social relations they would like to see in a revolutionary future as much as possible in their day to day lives. How do Jean Grave and his publications fit that? How does he enact—or does he enact—the kind of anarchist relations that presumably he would have wanted to see in a revolutionary society? CB: That's a very problematic area for Grave. The papers were notorious—perhaps unfairly so—for being places where Grave shared his point of view, and allowed people with whom he agreed to share their point of view. So, you might say, if we go with a prefigurative hypothesis, that his vision of an anarchist society was very much ‘everybody does what Grave has said should be done’. He was infamously nicknamed the Pope on rue Mouffetard [the place where his publications were printed] by the anarchist Charles Malato, in reference to this alleged dogmatism. That’s one aspect which I’ve tried to correct in the book. The papers were actually quite collective, collaborative endeavours. I've mentioned syndicalism and Grave’s defiance toward syndicalism, and yet the pro-syndicalism anarchist and labour activist Paul Delesalle had a syndicalist column there for a very long time, and Grave really engaged with it. More broadly, if we look at some of his archives, his letters, he did reject some material submitted to the paper. For the literary supplement, I remember one letter where he says “I can’t publish this, the quality of the verse is insufferable, I’m not going to publish this!”. He was also prone to excommunication and personal quarrels but in the broader milieu of anarchism this was not specific to Grave. When things soured, relationships could become quite embittered and then individuals would be kicked out of groups… But I don't think Grave was necessarily as intolerant of personal and ideological difference as he's been portrayed. As I’ve mentioned, the papers were dialogic spaces: there were letters, and I must really emphasise again the paratextual elements, which allowed many voices and different currents into the paper. The last two pages were announcements for local meetings, book reviews written by different people… The contributions are very dialogic in that space, and I think that's one of the reasons why there was successful—and this was very much a deliberate approach on Grave’s part. And another aspect of this is the place where the papers were produced: his attic in the Rue Mouffetard. That was famously really, very open, including to spy infiltration. There was a limit to how many people could be there, because the attic was really small, but this was a very open space. There are so many stories shared by Grave or others of intruders, spies trying to infiltrate this space, there was a bit of dark tourism around it, but so many contemporary commentators stressed the openness of this place, and it seems clear that this shows a certain pedagogical outlook on what anarchism should be, and how important dialogue was to its construction. JEH: And I suppose it also fits in with the discussion about anarchist identity and what it meant to be an anarchist publisher in that in that period. Moving on to the theme of personal connections. One of the things that seems to be key to your study of anarchism through Jean Grave is the way in which his personal connections as well as his material position—his work, his way of working and his networks—made it possible for him to not only be a theorist of anarchism, but also a kind of unavoidable character at the time in the reconfiguration of anarchism in the late 19th and early 20th century. How important do you think investigating networks of personal relations is to the study of anarchism specifically or political ideologies more broadly? CB: I think it is really important. To take the example of Grave, one obvious aspect which has been under-explored is his friendship with Kropotkin, although there is a good deal of social history around Kropotkin at the moment—it’s the centenary of his passing. But looking at networks really allows us to show different sides of the movement and its protagonists, and the great deal of dialogue and collaboration that existed in anarchism. This is not specific to my research. Fairly recently, Iain McKay has studied how important these French periodicals were for the dissemination and elaboration of Kropotkin’s ideas.[1] So, if you bypass the friendship with Grave and the editorial partnership, which was so central and completely ignored until a few years ago, you really do miss on a really important aspect of the creation and diffusion of anarchist communism. It’s the same between Grave and Reclus: looking at egodocuments and less formal sources (typically letters and autobiographies), you can uncover many arguments about violence, and also debates about ivory tower anarchism, of which Grave was repeatedly accused. These seemingly casual discussions and letter exchanges shed light on the big debates which form the more official intellectual and political history of anarchism. With Grave, I became really interested in the course of my research in his second wife, Mabel Holland Grave. She was an absolutely fascinating character in the anarchist movement, in the fine British tradition of upper middle-class women’s anarchism. She comes a bit out of nowhere, after Kropotkin introduced them, with no clear journey to anarchism, for instance. She came from a very affluent background, was boarding-school educated, which was not necessarily a given even for a privileged woman in this period, and she became a regular partner of Grave, both personally and politically. She collaborated with him and contributed to the paper. Anarcha-feminism was not something Grave really engaged with at all, but then we look at the praxis and the way he dedicated a book to her, stressing that they’d worked on it together, for instance, the fact that she was clearly a partner and the beautiful illustrations which she contributed, along with her editorial input… You could say that’s even worse: he used and silenced the labour of his wife. However, that's not the way I interpreted it. I thought that it was interesting how, in his daily life, so if we talk about prefiguration, he seems to have been far more progressive than his writings might have let on. So, I do think these networks are crucial. And here I'm really talking about private life—but there are so many ways you can look at this: friendship, casual acquaintances… I loved reading Grave’s memoir, how he wrote about bumping into people in the street—activists he knew, anarchist or not—and how they would discuss this or that. That's the daily life of a social movement. And I think for anarchism this is so important. If you're looking at a movement—perhaps like Marxism, where the doctrine is elaborated in conferences, basically where there is a sense of strict sense of orthodoxy, where there are formal institutions at various levels and gatekeepers often occupying official roles, it's far more problematic. The same was probably true of the socialist parties emerging at the time. This is about the frameworks of political creation and channels of political dissemination. Anarchists did not have parties, and rarely had binding official documents. And so this allowed that kind of flexibility, whereby informal interactions become essential. For historians, this means that the social history of politics is immediately essential. This is true of any political movement, of course, but the because of the predominantly (an-)organisational character of anarchism, the social milieu is more obviously relevant. JEH: This is nicely tied to the next question I wanted to ask, which returns to prefigurative politics and the way in which personal connections and networks are linked to prefiguration. As you show, it's these networks and personal connections that put Grave on the map. It's because he is able to create and foster these connections that he is a key figure in late 19th-century anarchism. How does this role as a kind of rhizome, as a node in the network sit with anarchist politics? Does it lead to the kind of problems you were talking about, like gatekeeping? How does it fit with anarchism’s argument in favour decentralisation and the diffusion of power? CB: Yes, that's a very problematic point and is one of the things I really set out to investigate with the book. I've come to the perhaps generous conclusion that Grave was primarily genuinely interested in sharing knowledge and sharing anarchist ideas—sharing his own vision, one might say, but I don't think that's necessarily true. I think really the emphasis for him was on enabling discussion and spreading anarchist communism. I have come across discussions with Kropotkin where he says, “have you seen the number of ads we have in the paper this week?”, and that’s of course not commercial advertising but ads where people communicate and share information about local organisations. That was on the national scale, and Grave would also advertise meetings internationally. Grave was conscious of the authoritarian potential of centrality. He was definitely aware of the criticism that was levelled at him, and he does say this autobiography: “I did this because, basically, I was quite certain of what I was saying, and I had my vision and the paper had a special place in the global anarchist movement…”, that was his argument in upholding what might be considered a very dogmatic approach to anarchism and its daily politics. But, alongside this, and there was so much effort towards diffusion, toward sharing the paper, reporting on and encouraging local movements. The suspicion levelled at Grave, that he was focused on spreading his own, somewhat narrow conception of anarchism is obviously what we would call know diffusionism—this idea that French anarchism shone all over the world, from Paris, from the attic on the rue Mouffetard, and occasionally from London but that's about it. But there are discussions, in particular from Max Nettlau, that are absolutely staggering in how contemporary they sound in their critique of such diffusionist assumptions. There are records of Nettlau expressing that “sending a few dozen copies of La Révolte to Brazil is not going to bring about revolution in Brazil, you need to adjust your ideas a little…”. He was quite aware that sharing print material was not enough, and was also fraught with ideological assumptions. However, what is interestingly being discussed by historians of anarchism working on non-European areas—I'm thinking of Brazil and Asia, in particular—is the great effort that went into and adapting anarchist material to local circumstances. You can see from Grave and others that there was a great deal of effort spent in seeking information about international movements, to reflect their activities in the paper, but also to have the knowledge to discuss their situations. I think it's far more nuanced and horizontal vision that appears. This is really interesting for us, as contemporary historians looking at these circulations in the light of all the discussions about provincialising Europe, and I would say the anarchists didn't do too badly actually. JEH: Indeed, one of the other points that struck me when reading your book was how you seek to challenge the diffusionist narrative even as you focus on a Paris-based node for the circulation of anarchism. Do you think that the study of someone like Grave and his periodicals—who are, as you’ve said, connectors—and of anarchist print culture, more generally, may lead us to rethink the way in which anarchism circulated and reconfigured itself at the transnational and global levels? How can studying anarchist print culture help us provincialise Europe and European anarchism? CB: What is really great at the moment is that there are so many studies from a non-European perspective, discussing all of this. I'm thinking, for instance of and Nadine Willems’s work on Japanese anarchism and Ishikawa Sanshirō, but also Laura Galián’s work on anarchism in a range of (post-)colonial contexts in the South of the Mediterranean[2]. This is really fascinating work in showing different anarchist traditions, exploring new areas, showing how they've engaged with these European movements, but also questioning the very notion of anarchism. Of course, when French anarchism is exported, say to Argentina, where a book by Grave might be translated, its meaning changes automatically through this change of context. So, the more empirical data we have, the more studies we have, then the more we can start revising and understanding what happens in translation, and in a variety of cultural contexts. Print culture is a very good way of entering this because print was the prime medium for the global circulation of anarchism. And if you had people being mobile, they would set up or import papers, most of the time, so print culture is probably the best source that we have to study this. This also includes translations of major theoretical works and the international sale of pamphlets—these aspects are less well-known, for now at least, but can really help us understanding processes of local appropriation. [1] Iain McKay, "Kropotkin, Woodcock and Les Temps Nouveaux", Anarchist Studies 23(1) (2015), 62ff. [2] Nadine Willems, Ishikawa Sanshirō's Geographical Imagination: Transnational Anarchism and the Reconfiguration of Everyday Life in Early Twentieth-Century Japan (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020); Laura Galián, Colonialism, Transnationalism, and Anarchism in the South of the Mediterranean, (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). by William Smith

Deliberative democracy has arguably become the dominant—perhaps even hegemonic—paradigm within contemporary democratic theory.[1] The family of views associated with it converge on the core idea that democratic decisions should be the outcome of an inclusive and respectful process of public discussion among equals. The paradigm has evolved considerably over the previous decades, with an initial emphasis on the philosophical contours of public reason gradually morphing into a more empirical analysis of democratic deliberation within a range of institutional and non-institutional settings.

The ideological assumptions underlying deliberative democracy have surprisingly not received much attention, either within the field of ideology studies or political theory. It is a mistake to approach deliberative democracy as an ideology in its own right, but the normative aspirations and empirical assumptions of its orthodox iterations are clearly informed by liberalism and social democracy. It takes from liberalism the idea of citizens as autonomous agents that are capable of engaging in a mutual exchange of reasons with their peers. It takes from social democracy a progressive aspiration to refashion, though ultimately not abolish, the institutional architecture of an ailing representative system. This ideological fusion can be seen, at least in part, as a reaction to the rise of new social movements and the resurgence of interest in civil society that accompanied the end of the Cold War. The deliberative paradigm emerged as an attempt on the part of thinkers such as Joshua Cohen, James Bohman, Seyla Benhabib, and—most influentially—Jürgen Habermas to steer liberalism in a more radical democratic direction, while insisting that emancipatory political projects must commit to the system of rights that underpin liberal constitutional orders. The relative lack of attention to the ideological moorings of deliberative democracy is unfortunate for at least two reasons. First, it diminishes our understanding of the rivalry between the deliberative approach and alternative theories of democracy. It is, for instance, difficult to fully grasp what is at stake in the debates between deliberative democrats and their agonistic, participatory or realist interlocutors without appreciating their underlying ideological differences. Deliberative opposition to a resurgent conservatism and the far right should also be understood as a manifestation of its ideological commitments, rather than a mere expression of technocratic distaste for anti-rationalist populism. Second, it clouds our view of the extent to which deliberative democracy is itself a site of ideological contestation. This is, at least in part, an upshot of internal tensions. The liberal influence on deliberative democracy heightens its concern for preserving order in the face of disagreement and conflict, such that achieving an accommodation between opposing societal perspectives is thought to take priority over the achievement of substantive political reforms.[2] The more overtly leftist and emancipatory social-democratic influence is a countervailing force, which motivates criticism of the status quo and support for political change notwithstanding the risk that this may exacerbate political divisions.[3] There is, though, another process of ideological contestation at work. This process is revealed when we turn our gaze away from, as it were, the ‘centre’ of the deliberative paradigm, toward developments at its ‘periphery’.[4] There have, in recent years, been numerous attempts to implement recognisably deliberative practices within settings that are radically different to liberal democratic regimes. The most striking, in many respects, are the experiments with deliberative mechanisms in regions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Officials have periodically experimented with custom-made deliberative forums, as well as importing mini-public designs pioneered elsewhere.[5] The ideological underpinnings of these developments are difficult to map, though the influence of the prevailing doctrines of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and ideas that can be associated with certain interpretations of Confucianism are evident. Baogang He and Mark Warren draw a connection between the use of deliberative forums in the PRC and a practice of consultation and elite discussion that has ‘deep roots within Chinese political culture’. They describe these experiments as instances of ‘authoritarian deliberation’, which is in turn presented as the core feature of a ‘deliberative authoritarianism’ that might serve as a potential pathway for political reform in the PRC.[6] The radical protest movements of the twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries have also emerged as unexpected but notable sites of deliberation.[7] The democratic practices of these movements have evolved through an iterated process of experimentation, spanning, among others, the women’s liberation movement, the New Hampshire Clamshell Alliance, the Abalone Alliance, ACT UP, Earth First!, the global justice movement, and the transnational wave of ‘Occupy’ movements. These movements are ideologically heterogenous, but anarchism is a particularly prominent influence on their politics, cultures, and internal practices. I contend that we can analyse these practices as a kind of ‘anarchist deliberation’, which corresponds to the emergence of ‘deliberative anarchism’ as a process of political mobilisation among decentred and autonomous movements.[8] There may be some reticence in referring to ‘deliberation’ in these authoritarian and activist contexts, rather than similar but distinct concepts like ‘consultation’ or ‘participation’. The concept is nonetheless salient, as the practices under consideration are constituted by the adoption of a ‘deliberative stance’ on the part of participants. This stance, as defined by David Owen and Graham Smith, requires agents to enter ‘a relation to others as equals engaged in mutual exchange of reasons oriented as if to reaching a shared practical judgement’.[9] The adoption of deliberative practices in various institutional or cultural settings is shaped, at least in part, through the various ways in which this core deliberative norm can be refracted through contrasting ideological prisms. In authoritarian deliberation, for instance, the egalitarian logic of deliberation is strictly limited to the internal relations of forum participants, against a systemic backdrop characterised by highly inegalitarian concentrations of power. Anarchist deliberation, by contrast, is an intersubjective practice among activists that is shaped by the core ideological values of anti-hierarchy, prefiguration, and freedom.[10] These values underpin a communicative process that is premised upon horizontal relations among participants recognised as equals, within autonomous spaces that emerge more-or-less spontaneously in the course of political mobilisation or mutual aid. These dialogic and expressive processes are instantiated within the networked organisational forms that have become synonymous with anarchist-influenced movements. Consensus decision-making is adopted within affinity group and spokes-councils as a means of both reaching decisions in the absence of hierarchy and prefiguring alternatives to the majoritarian procedures favored by parliamentary bodies. The consensus process is favoured because it is thought to amplify the voice of participants in various ways, allowing for the inclusion of diverse forms of expression against the backdrop of supportive activist cultures and shared political traditions. The deliberative process performs important functional roles in political environments where alternative coordination mechanisms are prohibited by ideological commitments. Authoritarian deliberation, for example, facilitates the expression and transmission of public opinion to elites in circumstances where open debate and multi-party elections are not permitted. Anarchist deliberation, by contrast, enables heterogenous protest movements to arrive at collective decisions about goals and tactics in the avowed absence of centralised or top-down power structures. The General Assembly (GA) in Occupy Wall Street (OWS), for instance, at least initially performed the functional role of allowing participants to clarify shared values, agree on processes, decide upon actions and discuss whether the movement should adopt ‘demands’.[11] The debates that occurred in the GA evolved into something of existential import for the movement, in that it was in and through the substance and symbolism of these large scale procedures that OWS forged a collective identity. The ideological underpinnings of deliberative practices inform their character and complexion, as well as attempts to ensure their operational integrity. Authoritarian deliberation, as the name suggests, is characterised by extensive control of issues and agendas by political elites, albeit with scope for citizen participation in selecting from a range of predetermined policy options. Anarchist deliberation, as one would expect, is characterised by extensive participant control over agendas and debates, though there are a range of informal cultural norms that aim to ensure the fairness and transparency of the process. These norms are typically seen as more flexible and organic than the more formal rules that lend structure to deliberation within mini-publics in authoritarian or democratic contexts. A recurring and much-discussed problem is nonetheless the emergence of informal networks of power and influence among activists, which tends to prompt much soul searching about whether more formalised rules or procedures should be adopted. David Graeber documents a particularly fraught meeting of Direct Action Network activists, where deep ideological divisions emerged over an apparently innocuous proposal to tackle gender inequalities in their ranks through the use of a ‘vibes watcher’ or ‘third facilitator’. These debates, he argues, may seem incomprehensible to outsiders, but are a matter of great significance to activists intent upon taming the corrosive influence of power while preserving the ideological integrity and ties of solidarity that underpin their political association.[12] The deliberative practices that emerge in authoritarian regimes and activist enclaves are treated as curiosities by deliberative democrats, but not as matters of primary concern. This is, for the most part, because neither authoritarian deliberation nor anarchist deliberation exhibits any sort of connection to democracy as it is understood within mainstream deliberative theorising. The extent to which ideas and practices associated with deliberative democracy can be adapted within authoritarian regimes and radical activist networks nonetheless demonstrates the ideological fluidity of the broader paradigm. It is, in fact, possible to place the deliberative views discussed here on an informal spectrum. Each view affirms deliberation as an optimum means of generating collective opinions or arriving at collective decisions, though each takes its bearings from contrasting assumptions:

This spectrum captures the contrasting ideological influences shaping deliberative practices across diverse political and cultural contexts, enabling us to tease out interesting similarities and differences. Deliberative authoritarianism and deliberative democracy, for instance, converge in treating deliberation as a discursive practice that should exert a positive influence on state institutions at local or national levels, albeit with diametrically opposed visions of how state power should be constituted. Deliberative anarchism, by contrast, tends to resist any association with authoritarian or liberal democratic institutions, adopting an antagonistic and insurrectionary orientation toward state and non-state sources of hierarchy. There are, to be sure, profound challenges confronting each of these perspectives, such that there must be at least some doubt about their future prospects. Deliberative authoritarianism, for instance, appears to be far less viable as a developmental pathway for the PRC in light of the recent tightening of political controls under the premiership of Xi Jinping.[14] Deliberative democracy retains considerable hold over the imaginations of democratic theorists, but it is not clear whether and how it can shape democratic practices in an era of post-truth politics and increasing polarisation. Deliberative anarchism, for its part, may suffer from an ongoing fall-out from the various movements of the squares, which has seen intensifying criticism of a perceived tendency among radical activists to fetishise process over outcomes.[15] There are, notwithstanding these challenges, at least two lessons that we can take from setting out this informal spectrum of deliberative positions. First, it illustrates the reach and appeal of deliberation across contrasting political traditions. In other words, the basic idea of deliberation as a means of including persons in a common enterprise, pooling their experiences and perspectives, and arriving at collective views or decisions appears to cohere surprisingly well with a broad range of political ideologies and frameworks. This should temper superficial critiques of deliberation that casually dismiss it as a creature of liberal political morality. Second—and I think more significantly—it reveals the contingency and contestability of the ideological basis of deliberative democracy in progressivist liberalism and social democracy. Deliberative authoritarianism and deliberative anarchism may not, in the end, pose an enduring challenge to mainstream interpretations of deliberative democracy, but their emergence nonetheless demonstrates that alternative iterations of its core ideas are possible. This should again give pause to those who are too quick to criticise the paradigm as inherently wedded to a broadly reformist or even quietist outlook. It should also, conversely, guard against political complacency on the part of its adherents, standing as a permanent reminder that tethering the idea of public deliberation to the political and institutional horizons of the present is neither necessary nor—perhaps—desirable.[16] [1] A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). [2] M. Freeden, The Political Theory of Political Thinking: The Anatomy of a Practice, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 219-222. [3] M. A. Neblo, Deliberative Democracy Between Theory and Practice, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 36. [4] J. Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, trans. W. Rehg, (Cambridge: Polity, 1996). [5] W. Smith, ‘Deliberation Without Democracy? Reflections, on Habermas, Mini-Publics and China’, in T. Bailey (Ed.), Deprovincializing Habermas: Global Perspectives (New Delhi: Routledge, 2013), pp. 96-114. [6] B. He and M. Warren, ‘Authoritarian Deliberation: The Deliberative Turn in Chinese Political Development’, Perspectives on Politics, 9 (2011), pp. 269-289. He and Warren discuss numerous examples of deliberative consultation at local or regional levels in the PRC, such as the use of deliberative polling to establish budgeting priorities in Wenling City. These mini-publics are comprised of ordinary citizens allowed to select policy recommendation after a structured process of deliberation, but their agenda and remit remains under the control of local CCP officials. [7] F. Polletta, Freedom is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements, (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2002). [8] W. Smith, ‘Anarchist Deliberation’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 27:2 (2022), forthcoming. [9] D. Owen and G. Smith, ‘Survey Article: Deliberation, Democracy, and the Systemic Turn’, Journal of Political Philosophy, 23 (2015), pp. 213-234, at p. 228. [10] B. Franks, N. Jun and L. Williams (Eds), Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach, (London: Routledge, 2018). [11] N. Schneider, Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013), pp. 56-64. [12] D. Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography, (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2009), pp. 336-352. [13] He and Warren, ‘Authoritarian Deliberation’, p. 269. [14] L‐C. Lo, ‘The Implications of Deliberative Democracy in Wenling for the Experimental Approach: Deliberative Systems in Authoritarian China’, Constellations (2021), https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12546 [15] M. Fisher, ‘Indirect Action: Some Misgivings about Horizontalism’, in P. Gielen (Ed.), Institutional Attitudes: Instituting Art in a Flat World, (Valiz: Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 101-114. [16] I’d like to thank Marius Ostrowski for the invitation to write this post for Ideology Theory Practice and for his generous comments on the initial draft. by John-Erik Hansson

The pages of the Journal of Political Ideologies testify to the resurgence of interest in anarchism in the last couple of decades. The number of articles on anarchism in the journal has increased rapidly in recent years; the last five years alone has seen articles covering everything from punk collectives and non-domination to anarchist hybridisation with other ideologies. This suggests that there is more work to be done to reconsider anarchism as a dynamic ideology concerned with contemporary political problems.

Three recent works on anarchism, the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (2019), Anarchism: A Conceptual History (2018) and Kropotkin, Read and the Intellectual History of British Anarchism (2015), show how the field of anarchist studies has benefited from engaging with Michael Freeden’s morphological approach to the study of ideologies. They have done so in two ways. Firstly, from the perspective of political theory, these works—and especially the first two—have helped clarify the conceptual constellations of anarchism. This is useful for rethinking what contemporary anarchism is, even if the precise morphological structure of anarchism may still be up for debate. Secondly, from a more historical perspective, these works—and especially the first and third—have foregrounded the dynamic process of the constestation and decontestation of concepts. This helps us understand the agency of anarchist thinkers and activists in their geographical and chronological contexts and offers fresh and much needed perspectives on the intellectual history of anarchism. Beyond anarchism, this latter point hints at the potential rewards of a closer collaboration between historians of political thought and scholars in ideology studies. The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, edited by Carl Levy and Matthew Adams, is an essential resource for anyone interested in contemporary developments in anarchist studies. Its four parts provide a masterful overview of the theory, history, and practice of anarchism from a global perspective. Eschewing the well-trodden path of reconstructing anarchism and anarchist political theory on the basis of a set of canonical thinkers, the first part of the handbook introduces the subject through nine chapters dedicated to what the editors consider to be the “core problems / problématiques” of anarchism. This provides a solid base for understanding anarchism in the variety of traditions, historical circumstances, and applications presented in the rest of the work. The second, “core traditions”, outlines the diversity of intellectual and political tendencies in anarchism, from mutualism to anarcha-feminism, green anarchism, and post-anarchism. Part III of the handbook then deals with the history of the anarchist movement through a set of “key events” and moments from the late 18th to the 21st centuries; from the revolutions that form the historical perspective of early anarchism to the alterglobalisation movement. The last part explores the applications and limits of anarchist theories and perspectives. It explores the breadth of anarchist studies and suggests possible trajectories for the development of the field. Issues broached include, for example, anarchism’s relation to post-colonialism, indigeneity, food security, and digital society. As a whole, the handbook successfully delivers what the editors wanted: a “rich tour d’horizon” of anarchism and anarchist studies. Although the editors do not frame it this way, the first part provides one plausible way of considering the morphological structure of anarchism. It even might be seen as progressing from core to peripheral concepts. In this reading, the state, the individual, the community, and freedom stand at the core (chapters 2, 3, and 4). They constitute the basis of the identity of anarchism throughout its history and remain stable components of anarchism today, regardless of internal divisions between, for instance, anarcho-syndicalists, mutualists, and anarcho-communists. Political economy, social change, revolution, and organisation (chapters 5 and 6) can then be seen as adjacent concepts that help understand the grounds for internal divisions within anarchism. The emergence of different perspectives and arguments on the desirability and viability of an anarchist market society, for instance, explain the split between mutualists and anarcho-communists. Finally, cosmopolitanism, anti-imperialism, religion, and science appear as peripheral concepts (chapters 7–10). These are concepts that became part of anarchism’s morphology in more specific circumstances and that informed political action and fostered dialogue with other ideologies and intellectual traditions. Whether this is the best or most accurate conceptual characterisation of anarchism may be a matter of legitimate debate. As we will see with Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach, others exist. Still, it is a reasonable morphology. It accounts for the diversity of anarchist traditions and the distinctiveness of anarchism. To do so, it highlights many of the fault lines within anarchism and between anarchism and other major ideologies—such as liberalism or socialism—that have emerged over the last century and a half. The authors thus show that anarchism has been and remains a dynamic ideology, developed by a diverse set of actors in a variety of political and intellectual contexts. Moreover, chapters in this section are both analytical and programmatic. In his chapter on “Freedom” (chapter 4), Alex Prichard suggests that seeing anarchist freedom as a (radicalised) version of freedom as non-domination helps make sense of and overcome debates on the nature of liberty in anarchism. Contributors to the handbook not only track the different ways of thinking about the central concepts of anarchism, they also offer new perspectives on these concepts, thus feeding the process of (de)contestation. In that sense, part I of the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism both describes anarchism as an ideology but also intervenes in contemporary debates about its nature and identity. In Freeden’s terms, the handbook is at once interpretative and prescriptive; that is one of its strengths.[1] Although the editors of the handbook do not frame it as such, the perspective that emerges may usefully be seen as a historically inclined response to a slightly earlier volume: Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach, edited by Benjamin Franks, Nathan Jun, and Leonard Williams. Whereas the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism is a wide-ranging overview of the field of anarchist studies, the explicit purpose of this latter volume is to present anarchism’s morphological structure of core, adjacent, and peripheral concepts. Among the core concepts are to be found what the editors identify as anarchism’s “basic values”—anti-hierarchy, freedom, and prefiguration (chapters 1–3), and the concepts that ground what anarchists do—agency, direct action, and revolution (chapters 4–6).[2] Adjacent concepts—horizontalism, organisation, micropolitics. and economy (chapters 7–10)—complement the core and provide a more nuanced understanding of how anarchists think and act politically together. Finally, the peripheral concepts—intersectionality, reform, work, DIY [Do It Yourself], and ecocentrism (chapters 11–15)—relate the conceptual core of the ideology to more concrete forms of political actions given contemporary political concerns. As is to be expected, there is much overlap between the two morphologies. However, one of the central differences between may be the absence of a chapter entirely dedicated to the State in Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Other differences of note regard what I have identified as the peripheral concepts of the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism’s morphology. In Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach, they include notions such as intersectionality (chapter 11), DIY (chapter 14), and ecocentrism (chapter 15). By contrast, peripheral concepts of the handbook include, for example, religion and science (chapters 9 and 10). This suggests important differences of ideological commitments within anarchism—and there are—but there is another explanation for such variation. In my view, this has to do with the different intellectual projects related to anarchism that these two works pursue. The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism seems to me to be more concerned with anarchism’s history than Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. While the former volume builds a morphology that is perhaps more appropriate to understanding anarchism in the longue durée, the latter provides a morphology that is especially appropriate for both interpreting 21st century anarchism and defining possible political strategies for anarchists. By proposing a more systematic analysis of key concepts in anarchism, Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach suggests a definition of anarchism as a political ideology deeply embedded in contemporary politics. This proposed morphological structure, the editors hope, can then be used to spark further discussions in the field as well as suggest “the possibilities for developing solidarities based on shared norms and practices”.[3] However, this does not mean that the morphological structure proposed in The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism is solely historical and interpretative. While it recasts anarchism in its conceptual history, it suggests new paths to explore for contemporary scholars of anarchism and for anarchists alike. If Prichard’s account of anarchist freedom is correct, then new “solidarities” and discussions could emerge between contemporary anarchists and republicans and anarchists might be encouraged to rethink their approach to rulemaking in relation to those of other activists. Taken together, then, Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach and the first part of the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism offer two distinct perspectives on anarchism as a political ideology, by considering its relationship to different if broadly overlapping concepts. In and of itself, this is a valuable addition to discussions of contemporary anarchist political theory. What it also provides is a framework for recasting the intellectual history of anarchism. The development of anarchist ideology can be understood in terms of two intertwined dynamics: (1) that of the contestation and decontestation of concepts (including their adoption and abandonment), and (2) that of the ordering of concepts as core, adjacent, or peripheral. Late nineteenth-century debates in the First International, which led to clearer distinctions within socialism between Marxists and anarchists, are classic instances of particularly intense processes of ideological contestation and decontestation. Matthew Adams, in his chapter on “Anarchism and the First World War” in Part III of the Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism (chapter 23), makes the case that the diversity of anarchist responses to the First World War also constitutes a peculiarly intense moment of ideological contestation. He demonstrates how the disagreement on the war between Pëtr Kropotkin and his supporters (who supported the Entente) and Errico Malatesta and his supporters (who opposed the war altogether) was not so much a betrayal of anarchist ideas and ideals as a reconfiguration based on local circumstances. What makes Adams’s chapter particularly compelling, however, is what the framework of ideology studies lacks from theoretical perspective: an understanding and account of context. Against what social, cultural, political, and intellectual backdrop do the morphological structures of ideologies change? What local problems were thinkers and activists trying to solve? Combining the study of ideology and a broadly contextualist approach to intellectual history gives us the tools to rethink the development of traditions of thought as they become essential parts of political ideologies. Matthew Adams’s Kropotkin, Read, and the Intellectual History of British Anarchism, is a prime example of such a successful combination. It is an attempt to shed new light on and account for the development of (British) anarchism through the sustained contextualisation of the Pëtr Kropotkin’s and Herbert Read’s anarchist theories. It shows both continuities and discontinuities in the British anarchist tradition. Kropotkin and Read reformulated their commitments to “the rejection of authority encapsulated in the modern state, trust in the constructive abilities of free individuals, faith in the unitary potential of communalist ethics, and belief in the equity of communised distribution” to respond to locally specific circumstances and political languages. The consequence was that, while such core claims remained, new adjacent and peripheral claims were made. As Read contributed to the re-circulation of Kropotkin’s thought, he developed anarchist theory in directions which would either not have been available to or contextually strategic for Kropotkin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For instance, although Adams considers that Herbert Read developed a more systematic anarchism than is often recognised, he also demonstrates that the language and concepts of nineteenth-century sociology, so useful to Kropotkin, “could be an impediment” to the further circulation of his philosophy, which emphasised culture, art and aesthetics. Reviving Kropotkin’s ideas in the mid-twentieth century led Read to reformulate them and bring them in relation to new concepts in a new context, in which “systematic ambitions were unfashionable and brought to mind a particularly uninspiring form of Marxism”. The relative stability of the core claims of anarchism from Kropotkin to Read is then best understood as an agent-driven reconstruction of anarchism’s conceptual constellations, its morphological structure, given new political, social, and cultural contexts. The key to Adams’s insights into the intellectual history of (British) anarchism is methodological. His work testifies to the fruitfulness of the combination of a contextualist approach to the history of political thought and a morphological approach to the study of ideologies. The history of anarchism has benefited from this methodological insight, but other ideologies should as well. The field of the history of political thought as a whole would benefit from greater engagement with Freeden’s approach to ideologies. Conversely, the field of ideology studies would likely also benefit from greater engagement with more historical approaches, from contextualism to Begriffsgeschichte. Further embracing interdisciplinarity and such methodological combinations can only sharpen our understanding of the political ideologies and traditions that structured and continue to structure our worldviews. [1] Michael Freeden, “Interpretative Realism and Prescriptive Realism”, Journal of Political Ideologies 17(1) (2012), 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2012.651883. [2] Benjamin Franks, Nathan J. Jun, and Leonard A. Williams (eds.), “Introduction”, in Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach (New York: Routledge, 2018), 8. [3] Franks, Jun, and Williams, 10. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed