by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. by Katy Brown, Aurelien Mondon, and Aaron Winter

Discussion and debate about the far right, its rise, origins and impact have become ubiquitous in academic research, political strategy, and media coverage in recent years. One of the issues increasingly underpinning such discussion is the relationship between the far right and the mainstream, and more specifically, the mainstreaming of the far right. This is particularly clear around elections when attention turns to the electoral performance of these parties. When they fare as well as predicted, catastrophic headlines simplify and hype what is usually a complex situation, ignoring key factors which shape electoral outcomes and inflate far-right results, such as trends in abstention and distrust towards mainstream politics. When these parties do not perform as well as predicted, the circus moves on to the next election and the hype starts afresh, often playing a role in the framing of, and potentially influencing, the process and policies, but also ignoring problems in mainstream, establishment parties and the system itself—including racism.

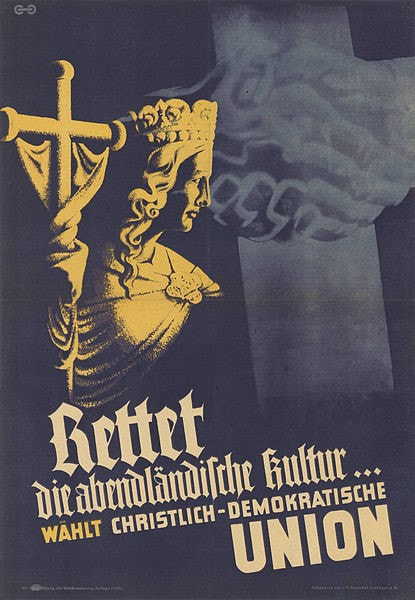

This overwhelming focus on electoral competition tends to create a normative standard for measurement and brings misperceptions about the extent and form of mainstreaming. Tackling the issue of mainstreaming beyond elections and electoral parties and more holistically does not only allow for more comprehensive analysis that addresses diverse factors, manifestations, and implications of far-right ideas and politics, but is much-needed in order to challenge some of the harmful discourses around the topic peddled by politicians, journalists, and academics. To do so, we must first understand and engage with the idea of the ‘mainstream’, a concept that has attracted very little attention to date; its widespread use has not been matched by definitional clarity or subjected to critical unpacking. It often appears simultaneously essentialised and elusive. Crucially then, we must stress two key points establishing its contingency and challenging its essentialised qualities. The first of these points is therefore that the mainstream is constructed, contingent, and fluid. We often hear how the ‘extreme’ is a threat to the ‘mainstream’, but this is not some objective reality with two fixed actors or positions. They are both contingent in themselves and in relation to one another. In any system, the construction and positioning of the mainstream necessitate the construction of an extreme, which is just as contingent and fluid. These are neither ontological nor historically-fixed phenomena and seeing them as such, which is common, is both uncritical and ahistorical. What is mainstream or extreme at one point in time does not have to be, nor remain, so. The second point is that the mainstream is not essentially good, rational, or moderate. While public discourse in liberal democracies tends to imbue the mainstream or ‘centre’ with values of reason and moderation, the reality can be quite different as is clearly demonstrated by the simple fact that what is mainstream one day can be reviled, as well as exceptionalised and externalised, as extreme the next, and vice versa. Racism would be one such example. As such, the mainstream is itself a normative, hegemonic concept that imbues a particular ideological configuration or system with authority to operate as a given or naturalise itself as the best or even only option, essential to govern or regulate society, politics and the economy. One of the main problems with the lack of clarity over the definition of the mainstream is that its contingency is masked through the assumption that it is common sense to know what it signifies, thus contributing to its reification as something with a fixed identity. Most people (including academics) feel they have a clear idea of what is mainstream; they position themselves according to what they feel/think it is and see themselves in relation to it. We argue that a critical approach to the mainstream, which challenges its status as a fixed entity with ontological status and essentialised ‘good’ and ‘normal’ qualities, is crucial for understanding the processes at play in the mainstreaming of the far right. To address various shortcomings, we define the process of mainstreaming as the process by which parties/actors, discourses and/or attitudes move from marginal positions on the political spectrum or public sphere to more central ones, shifting what is deemed to be acceptable or legitimate in political, media and public circles and contexts. The first aspect we draw attention to is the agency of parties and actors in the matter. Far-right actors are often positioned as agents, either unlocking their own success through internal strategies or pushing the mainstream to adopt positions that would otherwise be considered ‘unnatural’ to it. While we do not wish to dismiss the potential power of far-right actors to exert influence, it is essential to reflect on the capacity of the mainstream to shift the goalposts, especially given the heightened status and power that comes from the assumptions described above. What we highlight as particularly important is that shifts can take place independently and that the far right is not the sole actor which matters in understanding the process of mainstreaming. A far-right party can feel pressured or see an opportunity to become more extreme by mainstream parties moving rightward and thus encroaching on its territory. However, a far-right party can also be made more extreme without changing itself, but because the mainstream moves away from its ideas and politics. The issues associated with the assumed immovability and moderation of the mainstream have led towards a lack of engagement with the role of this group. It is therefore imperative to challenge these assumptions and capture the influence of mainstream elite actors, particularly with regard to discourse, in holistic accounts of mainstreaming. This leads on to one of the core tenets of our framework, which places discourse as a central feature with significant influence across other elements. Too often, discourse has been swallowed up within elections, seen solely as the means through which party success might be achieved, but we argue that it can stand alone and that the mainstreaming of far-right ideas is not something only of interest and concern when it is matched by electoral success. Our framework highlights the capacity of parties and actors from the far right or mainstream (though the latter has greatest influence) to enact discursive shifts that bring far-right and mainstream discourse closer or further from one another. Problematically, we argue, discourse is often seen solely in terms of its strategic effects for electoral outcomes. While we do not deny its importance in this regard, we suggest that discursive shifts may not always be connected in the ways we might expect with elections, and that the interpretation of electoral results can itself feed into the process of normalisation. First, changes at the discursive level do not always lead to a similar electoral trajectory, nor do the effects stop at elections: the mainstreaming of far-right ideas and narratives (including in and as policies) has the potential to both weaken the far right’s electoral performance if mainstream politicians compete over their traditional ground or bolster such parties by centring their ideas as the norm. Whatever the case, we must not lose sight of the effects on those groups targeted in such exclusionary discourse. The impact of mainstreaming does not stop at the ballot box. This feeds into the second key point about elections, in that the way they are interpreted can further contribute to normalisation, either through celebrating the perceived defeat of the far right or through hyping the position of far-right parties as democratic contenders. Certainly, this does not mean that we should not interrogate the reasons behind examples of increased electoral success among far-right parties, but that we must do so in a nuanced and critical manner. We must therefore guard against simplistic conclusions drawn from electoral, but also survey, data which we discuss at length in the article. Accounts of the electorate, often referred to through notions of ‘the people’ or ‘public opinion’, have tended to skew understandings of mainstreaming towards bottom-up explanations in which this group is portrayed as a collection of votes made outside the influence of elite actors. Through our framework, we seek to challenge these assumptions and instead underscore the critical role of discourse through mediation in constructing voter knowledge of the political context. Far from being a prescriptive framework or approach, our aim is to ensure that future engagement with the concept, process and implications of mainstreaming is based on a more critical, rounded approach. This does not mean that each aspect of our framework needs to be engaged with in great depth, but they should be considered to ensure criticality and rigour, as well as avoid both the uncritical reification of an essentially good mainstream against the far right, and the normalisation and mainstreaming of the far right and its ideas. We believe it is our responsibility as researchers to avoid the harmful effects of narrower interpretations of political phenomena which present an incomplete yet buzzword-friendly picture (i.e. ‘populist’ or ‘left behind’), often taken up in political and media discourse, and feed into further discursive normalisation. This brings us to the more epistemological, methodological, and political reason for the intervention and framework proposal: the need for a more reflective and critical approach from researchers, particularly where power and political influence are an issue. It is imperative that researchers reflect on their own role in contributing to the discourse around mainstreaming through their interpretations of related phenomena. This is important in the context of political and social sciences where, despite unavoidable assumptions, interests and influence, objectivity, and neutrality are often proclaimed. Necessarily, this demands from researchers an acknowledgement of their own positionality as not only researchers, but also as subjects within well-established and yet often invisibilised racialised, gendered, and classed power structures, notably those within and reproduced by our institutions, disciplines, and fields of study. 4/4/2022 The nationalism in Putin's Russia that scholars could not find but which invaded UkraineRead Now by Taras Kuzio

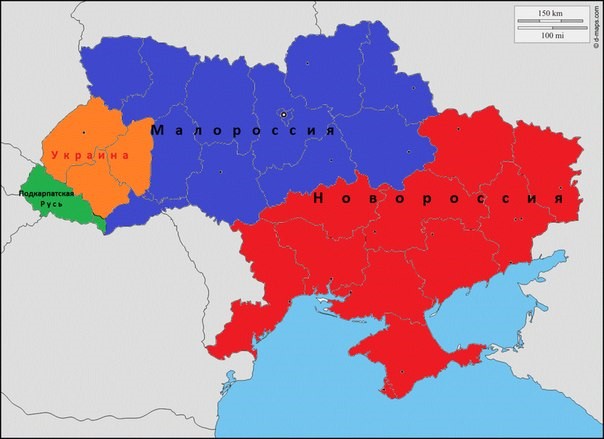

The roots of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are to be found in the elevation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré views, which deny the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[1] The Soviet Union recognised Ukrainians as a people separate but close to Russians. Russian imperial nationalists hold a Jekyll-and-Hyde view of Ukraine. While denigrating Ukraine in a colonial manner that would make even Soviet-era Communist Party leaders blush, Russian leaders at the same time claim to hold warm feelings towards Ukrainians, whom they see as the closest people to them. In this light, ‘bad’ Ukrainians are nationalists and neo-Nazis who want their country to be part of Europe; ‘good’ Ukrainians are obedient Little Russians who know their place in the east Slavic hierarchy and want to align themselves with Mother Russia. In other words, ‘good’ Ukrainians are those who wish their country to emulate Belarus. In practice, during the invasion, cities such as Kharkiv and Mariupol that have resisted the Russian incursion have been pulverised irrespective of the fact they are majority Russian-speaking. In turn, the fact of this resistance means to Russia’s leaders that these cities are inhabited by ‘Nazis’, not Little Russians who would have greeted Russian troops—and who should therefore be destroyed. Without an understanding of the deepening influence of Tsarist imperial nationalism in Russia since 2012, and especially following Crimea’s annexation in 2014, scholars will be unable to grasp or explain why Putin has been so obsessed with returning Ukraine to the Russian World—a concept created as long ago as 2007 as a body to unite the three eastern Slavs, which underpinned his invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Putin’s invasion did not come out of nowhere, but had been nurtured, discussed, and raised by Putin and Russian officials since the mid-2000s in derogatory dismissals of Ukrainians, and in territorial claims advanced against Ukraine. Unfortunately, few scholars took these at face value until summer 2021, when Putin published a long 6,000-word article[2] detailing his thesis about Russians and Ukrainians constituting one people with a single language, culture, and common history.[3] Ukrainians were a ‘brotherly nation’ who were ‘part of the Russian people.’ ‘Reunification’ would inevitably take place, Putin told the Valdai Club in 2017.[4] The overwhelming majority of scholarly books and journals have dismissed, ignored, or downplayed Russian nationalism as a temporary phenomenon.[5] Richard Sakwa claimed Putin was not dependent upon Russian nationalism, ‘and it is debatable whether the word is even applicable to him.’[6] Other scholars described it as a temporary phenomenon that had disappeared by 2015–16.[7] A major book on Russian nationalism published after the 2014 crisis included nothing on the incorporation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré discourse that dismissed the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[8] Russia’s invasion of Ukraine backed by Russian nationalist rhetoric has led to many Western academics suggesting that the Russian forces have ended up—or will end up—with egg on their faces. Why they felt the need to take this angle has varied, ranging from elaborate political science theories popular in North America about the nature of the Russian regime to the traditional Russophilia found among a significant number of Euro-American scholars writing about Russia.[9] As Petro Kuzyk pointed out, in writing extensively about Ukrainian regionalism, scholars have tended to exaggerate intra-Ukrainian regional divisions. [10] This has clearly been seen during the invasion, when Russia has found no support among Russian-speakers in cities such as Kharkiv, Mariupol, Odesa, and elsewhere. Furthermore, the prevailing consensus prior to the invasion among scholars and think tankers was eerily similar to that in Moscow; namely, that Ukraine would be quickly occupied, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy would flee, and Kyiv would be captured by Russian troops. That this did not happen again shows a a serious scholarly miscalculation about the strength of Ukrainian identity, and an overestimation of the strength of Russian military power.[11] Nationalism in Putin’s Russia has integrated Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms into an eclectic ruling ideology that drives the invasion. Putin, traditionally viewed as nostalgic for the Soviet Union, has also exhibited some pronounced anti-Soviet tendencies, above all in criticising Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin for creating a federal union of republics that included ‘Russian lands’ in the south-east, and artificially creating a ‘fake’ Ukrainian people. Putin’s invasion goal of ‘denazification’[12] aimed to correct this mistake by destroying the ‘anti-Russia’ nurtured by the West.[13] Both scholars and Russian leaders have been baffled as to how to understand and explain the tenacity of Ukrainian identity that has fought the Russian army to a standstill, and is now in the position of launching counterattacks. What is particularly difficult for Russian political leaders and media journalists to explain is how a people that supposedly does not exist (Ukrainians) could greet the ‘special military operation’ (Putin’s dystopian term for the invasion of Ukraine) not with bouquets of flowers but met it with armed resistance. Instrumentalism: Russian Nationalism as a Temporary Phenomenon Sakwa[14] writes that ‘the genie of Russian nationalism was firmly back in the bottle’ by 2016. Pal Kolstø and Marlene Laruelle, along similar lines, write that the nationalist rhetoric of 2014 was novel and subsequently declined.[15] Meanwhile, Henry Hale[16] also believes Putin was only a nationalist in 2014, not prior to the annexation of the Crimea or since 2015. Laruelle[17] concurs, writing that by 2016, Putin’s regime had ‘circled back to a more classic and pragmatic conservative vision’. Laruelle describes Putin’s regime as nationalistic only in the period 2013–16, arguing that ‘since then [it] has been curtailing any type of ideological inflation and has adopted a low profile, focusing on much more pragmatic and Realpolitik agendas at home and abroad.’[18] Paul Chaisty and Stephen Whitefield write, ‘Putin is not a natural nationalist’ and ‘[w]e do not see the man and the regime as defined by principled ideological nationalism.’[19] Sakwa[20] is among the foremost authors who deny that Putin is a nationalist, describing him as not an ideologue because he remains rational and pragmatic—which sharply contrasts with an invasion that most commentators view as irrational. Allegedly, moreover, there has been a ‘crisis’ in Russian nationalism.[21] Other scholars, meanwhile, believed that Putin ‘lost’ nationalist support.[22] In reality, the opposite took place. Russian imperial nationalism deepened, penetrated even further into Russian society and became dominant in Putin’s regime during the eight years between the invasions of Crimea and Ukraine. Russian imperial nationalist denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians became entrenched and have driven the invasion of Ukraine. Patriots and Conservatives - Not Nationalists Scholars described Russian nationalists as ‘patriots’ and western-style ‘conservatives.’ In the same year that the constitution was changed to allow Putin to remain president until 2036, Laruelle writes ‘the Putin regime still embodies a moderate centrist conservatism.’[23] Petro, Sakwa, and Robinson analogously describe a ‘conservative turn’ in Russian foreign policy.[24] If contemporary British conservatives annexed part of Ireland and denied the existence of the Irish people, “conservatism” would no longer fully capture the ideology they represented. By the same token, the Putin regime’s annexation of Crimea and denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians has sharply steered Russian conservatism towards the conceptual centrality of imperial nationalism. In their analyses, Sakwa and Anna Matveeva could only identify ‘militarised patriotism’ or elites divided into ‘westerners’ and ‘patriots.’[25] Following his 2012 re-election, Sakwa writes that Putin only spoke of ‘Russian identity discourse’ and Putin’s ‘conservative values’ which he believes should be not confused with a Russian nationalist agenda.[26] Sakwa has generally avoided using the term ‘nationalist’ when discussing Russian politicians. This created problems in explaining why a ‘non-nationalist’ Putin might choose to support a wide range of far-right and a smaller number of extreme left political movements in Europe and the US, ranging from national-conservatives, populist-nationalists, irredentist imperialists to neo-Nazis in Europe. Sakwa[27] attempts to circumvent this conundrum by relying on a portfolio of euphemistic alternatives, describing these far-right and extreme left movements as ‘anti-systemic forces,’ ‘radical left,’ ‘movements of the far right,’ ‘European populists,’ ‘traditional sovereigntists, peaceniks, anti-imperialists, critics of globalisation,’ ‘populists of left and right,’ and ‘values coalition.’ Putin’s Imperial Nationalist Obsession with Ukraine The Soviet regime recognised a separate Ukrainian people, albeit one that always retained close ties to Russians. The Ukrainian SSR was a ‘sovereign’ republic within the Soviet Union. In 1945, Joseph Stalin negotiated three seats at the UN for the USSR (representing the Russian SFSR), Ukrainian SSR, and Belarusian SSR. In the USSR, there was a Ukrainian lobby in Moscow, while this has been wholly absent under Putin.[28] Soviet nationality policy defined Ukrainians and Russians as related, but nevertheless separate peoples; this was no longer the case in Putin’s Russia. In the USSR, Ukraine, and the Ukrainian language ‘always had robust defenders at the very top. Under Putin, however, the idea of Ukrainian national statehood was discouraged.’[29] Although the USSR promoted Russification, it nevertheless recognised the existence of the Ukrainian language. For a decade prior to the invasion, the Ukrainian language was disparaged by the Russian media and political leaders as a dialect that was artificially made a language in the Soviet Union.[30] Russian nationalist myths and stereotypes underpinning the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had been raised, discussed, and threatened for over a decade prior to the ‘special military operation’. When Putin returned as president in 2012, he portrayed himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian [i.e., eastern Slavic] lands.’ Ukraine’s return to the Russian World, alongside Crimea and Belarus, was Putin’s unfinished business that he needed to accomplish before entering Russia’s history books. Ukraine, as a ‘Russian land’, should fall within the Russian World and remain closely aligned to Russia. Ukrainians, on this account, had no right to decide their own future. Russia sought to accomplish Ukraine’s return to the Russian World through the two Minsk peace agreements signed in 2014–15. Ukrainian leaders resisted Russian pressure to implement the agreements because they would have created a weak central government and federalised state where Russia would have inordinate influence through its proxy Donetsk Peoples Republic and Luhansk Peoples Republic. The failure of Russia’s diplomatic and military pressure led to a change in tactics in October 2021. Early that month, former President Dmitri Medvedev, now deputy head of Russia’s Security Council, penned a vitriolic attack on Ukrainian identity as well as an anti-Semitic attack on Jewish-Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ruling out further negotiations with Kyiv.[31] Medvedev claimed Ukrainian leaders were US puppets, and that therefore the Kremlin needed to negotiate directly with their alleged ‘puppet master’—Washington. Meanwhile, Russia would ‘wait for the emergence of a sane leadership in Ukraine,’ ‘who aims not at a total confrontation with Russia on the brink of war…but at building equal and mutually beneficial relations with Russia.’[32] Medvedev was revealing that Russia’s goal in any future military operation would be regime change, replacing an ‘anti-Russia’ leadership with a pro-Kremlin leader.[33] In early November 2021, Russia’s foreign policy machine mobilised and made stridently false accusations about threats from Ukraine and its ‘Western puppet masters.’ Russia began building up its military forces on the Ukrainian border and in Belarus. In December 2021, Russia issued two ultimatums to the West, demanding a re-working of European security architecture. The consensus within Euro-American commentary on the invasion has been that this crisis was completely artificial. NATO was not about to offer Ukraine membership, even though Ukraine had held periodic military exercises with NATO members for nearly three decades, while the US and NATO at no point planned to install offensive missiles in Ukraine. The real cause of the crisis was the failure of the Minsk peace process to achieve Ukraine’s capitulation to Russian demands that would have placed Ukraine within the Russian sphere of influence. After being elected president in April 2019, Zelenskyy had sought a compromise with Putin, but he had come round to understanding that this was not on offer. The failure of the Minsk peace process meant Ukraine’s submission would now be undertaken, in Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s words, by ‘military-technical means’—that is, the ‘special military operation’ that began on 24 February 2022. Russian Imperial and White Émigré Nationalism Captures Putin’s Russia Downplaying, marginalising, and ignoring Russian nationalism led to the ignoring of Russian nationalism’s incorporation of Tsarist and White Russian émigré denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Marginal nationalism in the 1990s became mainstream nationalism in Russia in the 2000s under Putin when the ‘emergence of a virulent nationalist opposition movement took the mainstream hostage.’[34] The 1993 coup d’état against President Boris Yeltsin was led by a ‘red-brown’ coalition of pro-Soviet and far-right nationalists and fascists. The failure of the coup d’état and the electoral defeat of the Communist Party leader Gennadiy Zyuganov in the 1996 elections condemned these groups to the margins of Russian political life. At the same time, from the mid 1990s, the Yeltsin presidency moved away from a liberal to a nationalist foreign and security approach within Eurasia and towards the West. This evolution was discernible in the support given to a Russian-Belarusian union during the 1996 elections and in the appointment of Yevgeny Primakov as foreign minister. Therefore, the capture of Russia by the Soviet siloviki began with the Chairman of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Primakov, four years before the chairman of the Federal Security Service (FSB), Putin, was elected president. Under Primakov, Russia moved from defining itself as part of the ‘common European home’ to the country at the centre of Eurasia. Under Putin, the marginalised ‘red-brown’ coalition gradually increased its influence and broadened to include ‘whites’ (i.e., nostalgic supporters of the Tsarist Empire). Prominent among the ideologists of the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition was the fascist and Ukrainophobe Alexander Dugin, who has nurtured national-Bolshevik and Eurasianist political projects.[35] In the 2014 crisis, Dugin, then a professor at Moscow State University, stated: ‘We should clean up Ukraine from the idiots,’ and ‘The genocide of these cretins is due and inevitable… I can’t believe these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are wonderful Slavonic people. And this is a race of bastards that emerged from the sewer manholes.’[36] During the 2000s the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition came to prominence and Putin increasingly identified with its denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Tsarist imperial nationalism was integrated with Soviet nostalgia, Soviet traditions and symbols and historical myths, such as the Great Patriotic War. Since the mid 2000s, only five years into his rule, Putin spearheaded the rehabilitation of the White Russian émigré movement and reburial of its military officers, writers, and philosophers in Russia. These reburials took place at the same time as the formation of the Russian World Foundation (April 2007) and unification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the émigré Russian Orthodox Church (May 2007). These developments supercharged nationalism in Putin’s Russia, reinforced the Tsarist element in the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition and fuelled the growing disdain of, and antipathy towards Ukraine and Ukrainians that was given state support in the media throughout the two decades before the invasion.[37] Putin personally paid for the re-burial of White Russian émigré nationalists and fascists Ivan Ilyin, Ivan Shmelev, and General Anton Deniken, who called Ukraine ‘Little Russia’ and denied the existence of a separate Ukrainian nation. These chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians were typical of White Russian émigrés. Serhy Plokhy[38] writes, ‘Russia was taking back its long-lost children and reconnecting with their ideas.’ Little wonder, one hundred descendants of White Russian émigré aristocrats living in Western Europe signed an open letter of support for Russia during the 2014 crisis. Putin was ‘particularly impressed’ with Ilyin, whom he first cited in an address to the Russian State Duma as long ago as 2006. Putin recommended Ilyin to be read by his governors, senior adviser Vladislav Surkov, and Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev. The intention was to use Ilyin’s publications in the Russian state programme to inculcate ‘patriotism’ and ‘conservative values’ in Russian children. Ilyin was integrated into Putin’s ideology during his re-election campaign in 2012 and influenced Putin’s re-thinking of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands;’ that is, integrating Belarus and Ukraine into the Russian World, and specifically his belief that the three eastern Slavs constituted a pan-Russian nation.[39] Laruelle has downplayed the importance of Ilyin’s ideology, writing that he did not always propagate fascism, and that Putin only quoted him five times.[40] Yet Putin has not only cited Ilyin, but also asked Russian journalists whether they had read Deniken’s diaries, especially the parts where ‘Deniken discusses Great and Little Russia, Ukraine.’[41] Deniken wrote in his diaries, ‘No Russian, reactionary or democrat, republican or authoritarian, will ever allow Ukraine to be torn away.’[42] In turn, Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré denials of Ukraine and Ukrainians were amplified in the Russian media and in its information warfare for over a decade prior to the invasion. Ukraine and Ukrainians were mocked in the Russian media in a manner ‘typical in coloniser-colonised relationships.’[43] Russia and Russians were cast as superior, modern, and advanced, while Ukraine and Ukrainians were portrayed as backward, uneducated, ‘or at least unsophisticated, lazy, unreliable, cunning, and prone to thievery.’ As a result of nearly two decades of Russian officials and media denigrating Ukraine and Ukrainians these Russian attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians ‘are widely shared across the Russian elite and populace.’[44] This is confirmed by a March 2022 survey conducted by Russia’s last remaining polling organisation, the Levada Centre, which found that an astronomical 81% of Russians supporting Russian military actions in Ukraine. Among these supporters, 43% believe the ‘special military operation’ was undertaken to protect Russophones, 43% to protect civilians in Russian-occupied Donbas, 25% to halt an attack on Russia, and 21% to remove ‘nationalists’ and ‘restore order.’[45] Russian Imperial Nationalist Denigration and Denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians Russian imperial nationalist views of Ukraine began to reappear as far back as the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections, when Russian political technologists worked for pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych’s election campaign, producing election posters designed to scare Russian speakers in south-eastern Ukraine about the prospect of an electoral victory by ‘fascist’ and ‘nationalist’ Viktor Yushchenko. This was when Russia revived Soviet ideological propaganda attacks against Ukrainian nationalists as ‘Nazi collaborators.’ Putin’s cult of the Great Patriotic War has been intricately linked to the promotion of Russia as the country that defeated Nazism in World War II (this is not true as all the Soviet nations contributed to the defeat) and which today is fighting contemporary Nazis in Ukraine, Poland, the three Baltic states, and beyond. Ukraine’s four de-communisation laws adopted in 2015 were despised in Moscow for many reasons. The most pertinent to this discussion was one law that equated Nazi and Soviet crimes against humanity (which contradicted Putin’s cult of Stalin[46]) and another law that moved the terminology of Ukraine’s wartime commemorations from the 1941–45 ‘Great Patriotic War’ to ‘World War II’ of 1939–45.[47] One of the 2004 election posters, reproduced below, imagines Ukraine in typical Russian imperial nationalist discourse as divided into three parts, with west Ukraine as ‘First Class’ (that is, the top of the pack), central Ukraine as ‘Second Class’ and south-eastern Ukraine as ‘Third Class’ (showing Russian speakers living in this region to be at the bottom of the hierarchy). Poster Prepared by Russian Political Technologists for Viktor Yanukovych’s 2004 Election Campaign Text:Yes! This is how THEIR Ukraine looks. Ukrainians, open your eyes! The map of Ukraine in the above 2004 election poster is remarkably similar to the traditional Russian nationalist image of Ukraine reproduced below: Map of Russian Imperial Nationalist Image of Ukraine Note: From right to left: ‘New Russia’ (south-eastern Ukraine in red), ‘Little Russia’ (central Ukraine in blue), ‘Ukraine’ (Galicia in orange), ‘Sub-Carpathian Rus’ (green).

Putin’s Growing Obsession with Ukraine Ignored by Scholars Imperial nationalism came to dominate Russia’s authoritarian political system, including the ruling United Russia Party. Putin’s political system copied that of the late USSR, which in turn had copied East European communist regimes that had created state-controlled opposition parties to provide a fake resemblance of a multi-party system. In 1990, the USSR gave birth to the Liberal Democratic Party of the Soviet Union, becoming in 1992 the Liberal Democratic Party of the Russian Federation (LDPRF). Led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the LDPRF repeatedly made loud bellicose statements about Ukraine and the West. The LDPRF’s goal has always been to attract nationalists who would have otherwise voted for far-right political parties not controlled by the state. In the 1993 elections following the failed coup d’état, the LDPRF received 22.9% - more than the liberal Russia’s Choice Party (15%) and the Communist Party (KPRF). Under Putin, these state-sponsored political projects expanded to the extreme left through the national-Bolshevik Motherland Party, whose programme was written by Dugin, and the Just Russia Party, which was active in Russian-occupied Donbas. Putin’s authoritarian regime needs internal fifth columnists and external enemies. Domestically, these include opposition leaders such as Alexei Navalny, and externally ‘anti-Russia’ Ukraine and the West. Changes to the Russian constitution in summer 2020 extended the ability of Putin to remain president for fifteen years, but in effect made him president for life. Political repression and the closure of independent media increased after these changes, as seen in the attempted poisoning of Navalny, and grew following the invasion of Ukraine. In 2017, The Economist said it was wrong to describe Russia as totalitarian;[48] five years later The Economist believed Russia had become a totalitarian state.[49] A similar evolution has developed over whether Putin’s Russia could be called fascist. In 2016, Alexander J. Motyl’s article[50] declaring Russia to be a fascist state met with a fairly tepid reception. and widespread scholarly criticism.[51] Laruelle devoted an entire book to decrying Russia as not being a fascist state, which was ironically published a few weeks after Russia’s invasion.[52] By the time of the invasion, all the ten characteristics Motyl had defined as constituting a fully authoritarian and fascist political system in Russia were in place:

Fascists rely on projection; that is, they accuse their enemies of the crimes which they themselves are guilty of. This has great relevance to Ukraine because Russia did not drop its accusation of Ukraine as a ‘Nazi’ state even after the election of Zelenskyy, who is of Jewish-Ukrainian origins and whose family suffered in the Holocaust.[54] Indeed, civilian and military Ukrainians describe Russian invaders as ‘fascists,’ ‘racists’, and ‘Orks’ (a fictional character drawn from the goblins found in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings). After shooting and severely wounding a Ukrainian civilian, the Russian soldier stood over him saying ‘We have come to protect you.’[55] Another Russian officer said to a young girl captive: ‘Don’t be afraid, little girl, we will liberate you from Nazis.’[56] Putin and the Kremlin’s justification for their ‘special military operation’ into Ukraine was based on many of the myths and chauvinistic attitudes to Ukraine and Ukrainians that had been disseminated by Russia’s media and information warfare since the mid 2000s. Of the 9,000 disinformation cases the EU database has collected since 2015, 40% are on Ukraine and Ukrainians.[57] The EU’s Disinformation Review notes, ‘Ukraine has a special place within the disinformation (un)reality,’[58] and ‘Ukraine is by far the most misrepresented country in the Russian media.[59] Russia’s information warfare and disinformation has gone into overdrive since the 2014 crisis. ‘Almost five years into the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the Kremlin’s use of the information weapon against Ukraine has not decreased; Ukraine still stands out as the most misrepresented country in pro-Kremlin media.’[60] Since the mid 2000s, Russian media and information warfare has dehumanised Ukraine and Ukrainians, belittling them as unable to exist without external support.[61] In colonialist discourse, Ukrainians were mocked as dumb peasants who had no identity, did not constitute a real nation, and needed an ‘elder brother’ (US, Russia) to survive. Such discourse was reminiscent of European imperialists when discussing their colonies prior to 1945. Ukraine was repeatedly ridiculed as an artificial country and a failed, bankrupt state. Putin first raised this claim as far back as in his 2008 speech to the NATO-Russia Council at the Bucharest NATO summit.[62] Ukraine as a failed state is also one of the most common themes in Russian information warfare.[63] In 2014, the Ukrainian state allegedly collapsed, requiring Russia’s military intervention. The Ukrainian authorities were incapable of resolving their problems because Ukraine is not a real state and could not survive without trade with Russia. Russian disinformation claimed that Ukraine’s artificiality meant it faced territorial claims from all its neighbours. Central-Eastern European countries would put forward territorial claims towards western Ukraine. Russia has made territorial claims to south-eastern Ukraine (Novorossiya [New Russia] and Prichernomorie [Black Sea Lands]) since as far back as the 2008 NATO summit[64] and increased in intensity following the 2014 invasion of Crimea. Putin repeatedly condemned Lenin for including south-eastern Ukraine within the Soviet Ukrainian republic, claiming the region was ancient ‘Russian’ land.[65] Another common theme in the Russian media was that Ukraine was a land of perennial instability and revolution where extremists run amok, Russian speakers were persecuted, and pro-Russian politicians and media were repressed and closed. Ukrainian ‘nationalist’ and ‘neo-Nazi’ rule over Ukraine created an existentialist threat to Russian speakers. Putin refused to countenance the return of Ukrainian control over the Russian-Ukrainian joint border because of the alleged threat of a new ‘Srebrenica-style’ genocide of Russian speakers.[66] Putin used the empirically unsubstantiated claim that Russian speakers were subject to an alleged ‘genocide’ as justification for the ‘special military operation.’ On 16 March, the UN’s highest court, the International Court of Justice, threw out the Russian claim of ‘genocide’ and demanded Russia halt its war.[67] Putin and the Kremlin adopted the discourse of an artificial Ukrainian nation created as an anti-Russian conspiracy. Putin said: ‘The Ukrainian factor was specifically played out on the eve of World War I by the Austrian special service. Why? This is well-known—to divide and rule (the Russian people).’[68] Putin and the Kremlin incorporated these views of Ukraine and Ukrainians a few years after they had circulated within the extreme right in Russia. The leader of the Russian Imperial Movement, Stanislav Vorobyev said, ‘Ukrainians are some socio-political group who do not have any ethnos. They are just a socio-political group that appeared at the end of the nineteenth century by means of manipulation of the occupying Austro-Hungarian administration, which occupied Galicia.’[69] Vorobyev and Putin agreed with one another that ‘Russians’ were the most divided people in the world and believed Ukrainians were illegally occupying ‘Russian’ lands.[70] These nationalist myths were closely tied to another, namely that the West created a Ukrainian puppet state in order to divide the pan-Russian nation. Russia’s ‘special military operation’ is allegedly not fighting the Ukrainian army but ‘nationalists,’ ‘neo-Nazis and drug addicts’ supported by the West.[71] Putin has even gone so far as to deny that his forces are fighting the Ukrainian army at all, and has called on Ukrainian soldiers to rebel against the supposed ‘Nazi’ regime led by Zelenskyy—an especially cruel slur given that several generations of the latter’s family were murdered during the Holocaust. The Russian nationalist myth of a Ukrainian puppet state is a reflection of viewing it as a country without real sovereignty that only exists because it is propped up by the West. Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns also depicted dissidents and nationalists as puppets of Western intelligence services. Russian information warfare frequently described former President Petro Poroshenko and President Zelenskyy as puppets of Ukrainian nationalists and the West. [72] These Russian nationalist views have also percolated through into the writings of some Western scholars. Stephen Cohen, a well-known US historian of Russia and the Soviet Union, described US Vice President Joe Biden as Ukraine’s ‘pro-consul overseeing the increasingly colonised Kyiv.’[73] President Poroshenko was not a Ukrainian leader, but ‘a compliant representative of domestic and foreign political forces,’’ who ‘resembles a pro-consul of a faraway great power’ running a ‘failed state.’[74] Cohen, who was contributing editor of the left-wing The Nation magazine, held a derogatory view towards Ukraine as a Western puppet state, which is fairly commonly found on the extreme left in the West, and which blamed the West (i.e., NATO, EU enlargement) for the 2014 crisis, rather than Putin and Russia. Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns routinely attacked dissidents and nationalist opposition as ‘bourgeois nationalists’ who were in cahoots with Nazis in the Ukrainian diaspora and in the pay of Western and Israeli secret services. Ukraine has been depicted in the Russian media since the 2004 Orange Revolution as a country ruled by ‘fascists’ and ‘neo-Nazis.’[75] A ‘Ukrainian nationalist’ in the Kremlin’s eyes is the same as in the Soviet Union; that is, anybody who supports Ukraine’s future outside the Russian World and USSR. All Ukrainians who supported the Orange and Euromaidan Revolutions and are fighting Russia’s ‘special military operation’ were therefore ‘nationalists’ and ‘Nazis.’ Conclusion Between the 2004 Orange Revolution and Putin’s re-election in 2012, Russian imperial nationalism rehabilitated Tsarist imperial and White Russian émigré dismissals of Ukraine and Ukrainians into official discourse, military aggression, and information warfare. In 2007, the Russian World Foundation was created and two branches of the Russian Orthodox Church were re-united. Returning to the presidency in 2012, Putin believed he would enter Russian history as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands’ which he proceeded to undertake with Crimea (2014), Belarus (2020), and Ukraine (2022). The origins of Putin’s obsession with Ukraine lie in his eclectic integration of Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms. The former provides the ideological bedrock for the denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians while the latter provides the ideological discourse to depict as Nazis all those Ukrainians who resist being defined as Little Russians. Putin believed his military forces would be greeted as liberators by Little Russians eager to throw off the US imposed nationalist and neo-Nazi yoke, the artificial Ukrainian state would quickly disintegrate, and the country and capital city of Kyiv would be taken within two days. Russian troops brought parade uniforms to march down Kyiv’s main thoroughfare and victory medals to be awarded to troops. This was not to be, because Putin’s denial of a Ukrainian people is—put simply—untrue. The Russo-Ukrainian war is a clash between twenty-first century Ukrainian patriotism and civic nationalism, as evidenced by Zelenskyy’s landslide election, and rooted in a desire to leave the USSR behind and be part of a future Europe, and nineteenth-century Russian imperial nationalism built on nostalgia for the past. Unfortunately, many scholars working on Russia ignored, downplayed, or denied the depth, direction, and even existence of nationalism in Putin’s Russia and therefore find unfathomable the ferocity, and goals behind the invasion of Ukraine. This was because many scholars wrongly viewed the 2014 crisis as Putin’s temporary, instrumental use of nationalism to annex Crimea and foment separatism in south-eastern Ukraine. Instead, they should have viewed the integration of Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms from the mid 2000s through to the invasion as a continuous, evolutionary process that has led to the emergence of a fascist, totalitarian, and imperialist regime seeking to destroy Ukrainian identity. [1] See Taras Kuzio, Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War: Autocracy-Orthodoxy-Nationality (London: Routledge, 2022). [2] Vladimir Putin, ‘Pro istorychnu yednist rosiyan ta ukrayinciv,’ 12 July 2021. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66182?fbclid=IwAR0Wj7W_7QL2-IFInLwl4kI1FOQ5RxJAemrvCwe04r8TIAm03rcJrycMSYY [3] Y.D. Zolotukhin, Bila Knyha. Spetsialnykh Informatsiynykh Operatsiy Proty Ukrayiny 2014-2018, 67-85. [4] Vladimir Putin, ‘Speech to the Valdai Club,’ 25 October 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvY184FQsiA [5] Anna Matveeva, A. (2018). Through Times of Trouble. Conflict in Southeastern Ukraine Explained From Within (Lanham, MA: Lexington Books, 2018), 182, 218, 221, 223, 224, 277. [6] Richard Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest. The Post-Cold War Crisis of World Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 125. [7] Pal Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again,’ Slavic Review, 75: 3 (2016), 702-725; Henry E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia,’ In: Pal Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud eds., The New Russian Nationalism. Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 221-248, at p.246; Marlene Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’ Journal of Democracy, 31: 3 (2020: 115-129. [8] P. Kolstø and H. Blakkisrud eds., The New Russian Nationalism. Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016). [9] For a full survey see T. Kuzio, ‘Euromaidan Revolution, Crimea and Russia-Ukraine War: Why it is Time for a Review of Ukrainian-Russian Studies,’ Eurasian Geography and Economics, 59: 3-4 (2018), 529-553 and Crisis in Russian Studies? Nationalism (Imperialism), Racism, and War (Bristol: E-International Relations, 2020), https://www.e-ir.info/publication/crisis-in-russian-studies-nationalism-imperialism-racism-and-war/ [10] See Petro Kuzyk, ‘Ukraine’s national integration before and after 2014. Shifting ‘East–West’ polarization line and strengthening political community,’ Eurasian Geography and Economics, 60: 6 (2019), 709-735/ [11] T. Kuzio, ‘Putin's three big errors have doomed this invasion to disaster,’ The Daily Telegraph, 15 March 2022. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/03/15/putins-three-big-errors-have-doomed-invasion-disaster/ [12] ‘Do not resist the liberation,’ EU vs Disinfo, 31 March 2022. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/do-not-resist-the-liberation/ [13] T. Kuzio, ‘Inside Vladimir Putin’s criminal plan to purge and partition Ukraine,’ Atlantic Council, 3 March 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/inside-vladimir-putins-criminal-plan-to-purge-and-partition-ukraine/ [14] R. Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 159. [15] P. Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again’ and M. Laruelle, ‘Is Nationalism a Force for Change in Russia?’ Daedalus, 146: 2 (2017, 89-100. [16] H. E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia.’ [17] M. Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’126. [18] M. Laruelle, ‘Ideological Complimentarity or Competition? The Kremlin, the Church, and the Monarchist Idea,’ Slavic Review, 79: 2 (2020), 345-364, at p.348. [19] Paul Chaisty and Stephen Whitefield, S. (2015). ‘Putin’s Nationalism Problem’ In: Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and R. Sakwa eds., Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives (Bristol: E-International Relations, 2015), 165-172, at pp. 157, 162. [20] R. Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine. Crisis in the Borderlands (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015) and Russia Against the Rest. [21] Robert Horvath, ‘The Euromaidan and the crisis of Russian nationalism,’ Nationalities Papers, 43: 6 (2015), 819-839. [22] P. Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again’ and H. E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia.’ [23] M. Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’126. [24] R. Sakwa, ‘Is Putin an Ism,’ Russian Politics, 5: 3 (2020): 255-282, at pp.276-277; Neil Robinson, ‘Putin and the Incompleteness of Putinism,’ Russian Politics, 5: 3 (2020): 283-300, at pp.284-285, 287, 289, 293, 299); Nicolai N. Petro, ‘How the West Lost Russia: Explaining the Conservative Turn in Russian Foreign Policy,’ Russian Politics, 3: 3 (2018): 305-332. [25] A. Matveeva, Through Times of Trouble, 277 and Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 119. [26] R. Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 125, 189. [27] Ibid., 60, 75, 275, 276. [28] Mikhail Zygar, All the Kremlin’s Men. Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin (New York: Public Affairs, 2016), 87. [29] Ibid., [30] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukrainian-literary-language-is-an-artificial-language-created-by-the-soviet-authorities/ [31] https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5028300 [32] Ibid., [33] Taras Kuzio, ‘Medvedev: The Russian-Ukrainian War will continue until Ukraine becomes a second Belarus,’ New Eastern Europe, 20 October 2021. https://neweasterneurope.eu/2021/10/20/medvedev-the-russian-ukrainian-war-will-continue-until-ukraine-becomes-a-second-belarus/ [34] Charles Clover, Black Wind, White Snow. The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), 287. [35] M. Laruelle, ‘The three colors of Novorossiya, or the Russian nationalist mythmaking of the Ukrainian crisis,’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 3: 1 (2016), 55-74. [36] Mykola Riabchuk, ‘On the “Wrong” and “Right” Ukrainians,’ The Aspen Review, 15 March 2017. https://www.aspen.review/article/2017/on-the-wrong-and-right-ukrainians/ [37] Anders Aslund, ‘Russian contempt for Ukraine paved the way for Putin’s disastrous invasion,’ Atlantic Council, 1 April 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russian-contempt-for-ukraine-paved-the-way-for-putins-disastrous-invasion/ [38] Serhy Plokhy, Lost Kingdom. A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin (London: Penguin Books, 2017), 327. [39] Ibid., 332. [40] M. Laruelle, ‘In Search of Putin’s Philosopher,’ Intersection, 3 March 2017. https:// www.ponarseurasia.org/article/search-putins-philosopher [41] S. Plokhy, Lost Kingdom, 326. [42] Ibid., [43] Alena Minchenia, Barbara Tornquist-Plewa and Yulia Yurchuk ‘Humour as a Mode of Hegemonic Control: Comic Representations of Belarusian and Ukrainian Leaders in Official Russian Media’ In: Niklas Bernsand and B. Tornquist-Plewa eds., Cultural and Political Imaginaries in Putin’s Russia (Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2018), 211-231, at p.225. [44] Ibid, 25 and Igor Gretskiy, ‘Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy – The Case of Ukraine,’ Saint Louis University Law Journal, 64:1 (2020), 1-22, at p.21. [45] https://www.levada.ru/2022/03/31/konflikt-s-ukrainoj/ [46] T. Kuzio, ‘Stalinism and Russian and Ukrainian National Identities,’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 50, 4 (2017), 289-302 . [47] Anna Oliynyk and T. Kuzio, ‘The Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity, Reforms and De-Communisation in Ukraine,’ Europe-Asia Studies, 73: 5 (2021), 807-836. [48] Masha Gessen is wrong to call Russia a totalitarian state,’ The Economist, 4 November 2017. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2017/11/02/masha-gessen-is-wrong-to-call-russia-a-totalitarian-state [49] ‘The Stalinisation of Russia,’ Economist, 12 March 2022. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/03/12/the-stalinisation-of-russia [50] Alexander J. Motyl, ‘Putin’s Russia as a fascist political system,’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 49: 1 (2016), 25-36. [51] I was guest editor of the special issue of Communist and Post-Communist Studies and remember the controversies very well as to whether to publish or not publish Motyl’s article. [52] M. Laruelle, Is Russia Fascist ? Unraveling Propaganda East and West (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2022). [53] Olga Kryshtanovskaya and Stephen White, ‘Putin's Militocracy,’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 19: 4 (2003), 289-306. [54] Zelenskyy is the grandson of the only surviving brother of four. The other 3 brothers were murdered by the Nazi’s in the Holocaust. [55] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/19/we-have-to-come-to-protect-you-russian-soldiers-told-ukrainian-man-theyd-shot [56] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/20/world/europe/russian-soldiers-video-kyiv-invasion.html [57] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-will-turn-into-a-banana-republic-ukrainian-elections-on-russian-tv/?highlight=ukraine%20land%20of%20fascists [58] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/what-didnt-happen-in-2017/?highlight=What%20didn%26%23039%3Bt%20happen%20in%202017%3F [59] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-under-information-fire/ [60] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-under-information-fire/?highlight=ukraine [61] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/dehumanizing-disinformation-as-a-weapon-of-the-information-war/?highlight=Ukraine%20has%20a%20special%20place%20within%20the%20disinformation%20%28un%29reality [62] https://www.unian.info/world/111033-text-of-putin-s-speech-at-nato-summit-bucharest-april-2-2008.html [63] Yuriy D. Zolotukhin Ed., Bila Knyha. Spetsialnykh Informatsiynykh Operatsiy Proty Ukrayiny 2014-2018 (Kyiv: Mega-Pres Hrups, 2018), 302-358. [64] https://www.unian.info/world/111033-text-of-putin-s-speech-at-nato-summit-bucharest-april-2-2008.html [65] T. Kuzio, Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War,1-34. [66] ‘Putin fears second “Srebrenica” if Kiev gets control over border in Donbass,’ Tass, 10 December 2019. https://tass.com/world/1097897 [67] https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/182 [68] V. Putin, ‘Twenty questions with Vladimir Putin. Putin on Ukraine,’ Tass, 18 March 2020. https://putin.tass.ru/en [69] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZD62ackWGFg [70] V. Putin, ‘Ukraina – samaya blyzkaya k nam strana,’ Tass, 29 September 2015. https://tass.ru/interviews/2298160 and ‘Speech to the Valdai Club,’ 25 October 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvY184FQsiA [71] ‘Putin references neo-Nazis and drug addicts in bizarre speech to Russian security council – video,’ The Guardian, 25 February 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2022/feb/25/putin-references-neo-nazis-and-drug-addicts-in-bizarre-speech-to-russian-security-council-video [72] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/zelenskyys-ruling-is-complete-failure-nazis-feel-well-ukraine-remains-anti-russia/ [73] Stephen Cohen, War with Russia?: From Putin & Ukraine to Trump and Russiagate (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2019), 145. [74] Ibid., p. 36. [75] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-will-turn-into-a-banana-republic-ukrainian-elections-on-russian-tv/?highlight=ukraine%20land%20of%20fascists by Federico Tarragoni

In an old textbook on populism, the psycho-sociologist Alexandre Dorna described the phenomenon as a 'volcanic eruption': a surge of the repressed impulses, instincts and fantasies of the masses onto the political scene.[1] This analysis is very common today, especially in relation to the so-called 'far-right populisms', such as the governments of Trump, Bolsonaro, or Orbán. We will not be talking here about the fantasies (in a Freudian sense) of which populism would be the political vector, but about those that it expresses in the speaker who speaks about it. What exactly are we saying when we categorise something as 'populist'? It is well known that the word is used more to stigmatise than to designate positively. Its proliferation in public debate over the past decade has been unprecedented: in 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary awarded it 'word of the year'. Its inflation in the public debate points to the undeniable re-emergence of the ‘people’ as political operator, especially since the subprime crisis of 2008. On the extreme right, this resurgence is expressed in xenophobic nativist movements that oppose the national people to immigration and to ethnic and sexual minorities. On the far left, it appears in plebeian movements that oppose the ‘people’ as a democratic subject to a ruling class, judged to be in collusion with neoliberal economic elites, and accused of corrupting democracy. Both renewals emerge in the global political space. While the former may be compatible with a neoliberal economic orientation, as in the cases of Trump and Bolsonaro, the latter is in frontal opposition.