by Sean Seeger

What is the relationship of queer theory to utopianism?

Given their mutual interest in challenging dominant norms, values, and institutions, it may seem obvious that queer theory would share affinities with utopian thought. Determining what precisely these affinities consist in is, however, a less straightforward matter. In order to understand them, we will need to consider the twin careers of queer theory and utopianism over the last few decades. It is a striking fact that the flourishing of the first wave of queer theory in the 1980s and 90s coincided with the demise of utopianism within wider culture. Theorists from David Harvey to Fredric Jameson have explained this drying up of utopian energy in terms of the turn toward post-Fordism followed by the rise of neoliberalism.[1] Others, such as Ruth Levitas and Slavoj Žižek, have emphasised the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 as key factors in the widely proclaimed ‘death’ of utopia.[2] Meanwhile, in their analyses of the cultural politics of the period, Franco Berardi and Mark Fisher each write of the widespread sense of ‘the cancellation of the future’ as it became increasingly hard to envisage plausible alternatives to capitalism during these decades.[3] As James Ingram notes, this anti-utopian sense of stagnation meant that critics of the status quo found it necessary to seize on ‘ever thinner, weaker, and vaguer’ utopian moments as the possibility of tangible, real-world change receded from view.[4] Utopianism thus tended to become highly abstract and emptied of content: rather than anticipating a better society or the liberation of specific human energies, the focus of much utopian discourse increasingly became the bare possibility of change itself – the intimation that things might, somehow, someday be otherwise. A case in point is that of Jameson’s Archaeologies of the Future, where it is suggested that, in light of the failed utopian projects of the twentieth century, ‘the slogan of anti-anti-Utopianism might well offer the best working strategy’ for those on the left today.[5] On this view, rearguard action against the dystopian tendencies of late capitalism, combined with fleeting glimpses of utopian hope found scattered amidst works of literature and popular culture, may be as close to utopia as we are able to come. This anti-utopian turn was arguably foreshadowed in certain respects by the work of Michel Foucault, who, in response to an interviewer’s question about why he had not sketched a utopia, notoriously replied that ‘to imagine another system is to extend our participation in the present system.’[6] In their book, The Last Man Takes LSD: Foucault and the End of Revolution, Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora show that this outlook was the result of a growing sense of exhaustion with system building, utopian dreaming, and grand visions of the future in the latter half of the twentieth century.[7] In place of revolution, they argue, Foucault proposed a turn toward the self and a focus on micro-political as opposed to systemic change. Foucault’s late masterwork, The History of Sexuality, published in several volumes between 1976 and 1984, is representative of this inward turn. It was also to be one of the main sources of inspiration for what was to become known as queer theory. In this context, it is worth noting that a related criticism to that levelled by Ingram at the diminished utopianism of the 80s and 90s has also been made of first-wave queer theory. A good example of this is Rosemary Hennessy’s book Profit and Pleasure, in which Hennessy criticises what she sees as the tendency of theorists like Judith Butler and Eve Sedgwick to separate gender and sexuality from capitalism and class.[8] Such an approach is problematic, firstly, because it dehistoricises gender and sexuality by untethering them from the development of capitalism, and, secondly, because it dematerialises them by emphasising their cultural construction while neglecting socioeconomic factors such as the changing nature of wage labour or the origins of the modern family. Hennessy is one of a number of critics who see queer theory’s way of engaging gender and sexuality as restrictive and as leading to difficulties in situating queer identity and politics in relation to broader social developments.[9] Although they do not generally frame these limitations in terms of a failure of the utopian imagination, a parallel may be drawn between these writers’ critique of queer theory, on the one hand, and critiques of the turn toward micro-politics during the 80s and 90s by commentators like Dean and Zamora, on the other. Just as utopianism dwindled to little more than a wisp of possibility during the neoliberal era, so first-wave queer theory represents for some of its critics a retreat from large-scale social critique in favour of a preoccupation with individual self-fashioning, leaving it susceptible to commodification and the dilution of its radical potential. These are serious charges. There are nevertheless a number of replies that queer theorists might make in response to them. A first would start by noting that, as queer theorists themselves, critics like Hennessy are contributors to the enterprise they find fault with. Insofar as their own class-based analysis of gender and sexuality is successful (as it arguably is), they thereby demonstrate that queer theory is able to encompass economic considerations. Although this does not constitute a defence of earlier theorists, it does help to demonstrate the flexibility of queer theory and the possibility of broadening its scope beyond the categories of gender and sexuality. Queer of color critique, which addresses the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race, has likewise contested some of queer theory’s guiding assumptions and highlighted further blindspots from a position within queer theory itself. A second reply would be to point out that some queer theorists have been concerned with capitalism and class since the inception of the field in the early 1980s. To take one prominent example, John D’Emilio was producing groundbreaking analysis of socioeconomic factors in the formation of queer subjectivity in articles such as ‘Capitalism and Gay Identity’ as early as 1983.[10] In the following decade, Lisa Duggan analysed the depoliticisation of gay identity in articles like ‘The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism.’[11] The main contention of D’Emilio’s ‘Capitalism and Gay Identity’ is that ‘only when individuals began to make their living through wage labor, instead of as parts of an interdependent family unit, was it possible for homosexual desire to coalesce into a personal identity – an identity based on the ability to remain outside the heterosexual family and to construct a personal life based on attraction to one’s own sex.’ This, in turn, ‘made possible the formation of urban communities of lesbians and gay men and, more recently, of a politics based on a sexual identity.’[12] D’Emilio’s account of the origin of gay identity is not deterministic: he does not claim that an alteration in economic life caused gay identity to come into existence. Rather, his argument is that until specific historical conditions arose there was no ‘social space’ for such an identity to occupy. D’Emilio shows that while same-sex desire is present in the historical record prior to the nineteenth century, homosexuality as an identity – as a way of being and of relating to others – is not. As even this brief sketch hopefully illustrates, D’Emilio’s work provides a prima facie reason to think that queer theory need not neglect economic considerations. A third reply to critics of queer theory’s limited political scope would be to reconsider some of its foundational texts. Reflecting on her classic study Gender Trouble a decade on from its original publication, Butler commented that ‘the aim of the text was to open up the field of possibility for gender without dictating which kinds of possibilities ought to be realized.’[13] The possibilities in question have to do with ways of performing gender, and the scope for subversion of established gender roles and styles. It is true, as Hennessy argues, that both Gender Trouble and its sequel, Bodies that Matter, focus almost exclusively on gender and sexuality and that neither offers anything like a systematic analysis of their relationship to capitalism or class. Whether this constitutes as decisive a shortcoming as Hennessy believes is less clear, however. ‘One might wonder,’ Butler writes, ‘what use “opening up possibilities” finally is, but no one who has understood what it is to live in the social world as what is “impossible,” illegible, unrealizable, unreal, and illegitimate is likely to pose that question.’[14] This is a suggestive observation that may point to a way of reappraising not only Gender Trouble but Butler’s work more generally. While taking the invalidation of certain ways of performing gender as its ostensible focus, the remark registers a concern with illegibility and illegitimacy that has continued to inform Butler’s work. In her books Precarious Life and Notes toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Butler incorporates economic marginalisation into her analysis and provides an insightful account of the condition of precarity, which she defines as differential exposure to economic insecurity, violence, and forced migration.[15] In light of these and other works, it has become possible to identify a persisting preoccupation on Butler’s part with the ways in which social value and legitimacy are assigned to or withheld from different groups, whether on the basis of gender, sexuality, race, class, immigration status, or some combination of these. The examples of D’Emilio and Butler serve to illustrate the social and political reach of queer theory. Recent years, however, have seen the rise of a more overtly utopian style of queer theory. Work in this vein explicitly repudiates the anti-utopianism of the neoliberal era and is influenced as much by traditions of radical queer activism and historical events such as the Compton’s Cafeteria riot and Stonewall as by Foucault’s History of Sexuality. Published in 2009, José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, an important example of queer of color critique, articulates a hopeful, future-oriented alternative to what Muñoz sees as the resignation and political timidity of queer culture since the turn of the millennium. Distinguishing between LGBT pragmatism and queer utopianism, Muñoz argues that in focusing on objectives like gay marriage or securing the right of trans people to serve in the military, the queer community has lost sight of the utopian aspirations that inspired activists of the 1960s and 70s. For Muñoz, the aim of queer politics ought to be nothing less than the achievement of a world no longer structured by heteronormativity or white supremacy, however remote such a goal may appear from our present dystopian vantage. Even if Cruising Utopia does not offer the kind of concrete detail required to realise such a project, it is clearly a long way from the micro-political tinkering associated with queer theory by some of its critics. A very different but no less utopian form of queer theory is found in The Xenofeminist Manifesto, originally published online in 2015 and authored by a collective of six authors working under the name Laboria Cuboniks. Characterised by Emily Jones as ‘a feminist ethics for the technomaterial world’,[16] xenofeminism is a queer technofeminism committed to trans liberation and gender abolition, by which is meant the construction of ‘a society where traits currently assembled under the rubric of gender, no longer furnish a grid for the asymmetric operation of power.’[17] The ethos of the manifesto is well captured by its subtitle: ‘a politics for alienation’. Those seeking radical change must embrace ‘alienation’ through the recognition that nothing is natural. While acknowledging the cultural construction of gender, the manifesto insists that materiality and biology must likewise not be taken as givens: they can be intervened in through surgery, hormone therapies, and alterations to the built environment. As experiments in free and open-source medicine on the part of feminists, gender hacktivists, and trans DIY-HRT forums demonstrate, technologies so far captured by capital may yet be repurposed as part of an anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal project in which ‘women, queers, and the gender non-conforming play an unparalleled role.’[18] Written in a self-consciously hyperbolic style and blending promethean rhetoric with quasi-science fictional projections of post-capitalist emancipation, The Xenofeminist Manifesto is as exhilarating as it is wildly ambitious. What, then, is the relationship of queer theory to utopianism? Based on our brief consideration of some of queer theory’s more utopian elements, it is reasonable to draw two provisional conclusions: that queer theory may have more in common with utopian thought than is often assumed, and that there are signs of a more explicit utopian turn taking place within queer theory today. It remains to be seen how far the latter will inform future queer politics. My thanks to Daniel Davison-Vecchione for his helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this essay. [1] See David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); and Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1991). [2] See Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia, 2nd edn. (Oxfordshire: Peter Lang, 2011), pp. ix–xv; and Slavoj Žižek, In Defense of Lost Causes (London: Verso, 2008). [3] See Franco Berardi, After the Future, eds. Gary Genosko and Nicholas Thoburn (Edinburgh and Oakland, Baltimore: AK Press, 2011); and Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (London: Zero, 2009). [4] James D. Ingram, Introduction, Political Uses of Utopia: New Marxist, Anarchist, and Radical Democratic Perspectives, eds. S. D. Chrostowska and James D. Ingram (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), p. xvi. [5] Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (London: Verso, 2007), xvi. [6] Michel Foucault, ‘Revolutionary Action: Until Now,’ in Language, Counter-Memory and Practice, ed. Donald F. Bouchard (New York: Cornell University Press, 1977), p. 230. [7] Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora, The Last Man Takes LSD: Foucault and the End of Revolution (London: Verso, 2021). [8] Rosemary Hennessy, Profit and Pleasure: Sexual Identities in Late Capitalism, 2nd edn. (New York: Routledge, 2017). [9] Related issues have been raised about queer theory by James Penney in After Queer Theory: The Limits of Sexual Politics (London: Pluto, 2014), which makes the case for the need for a critical return to Marxism on the part of queer theorists. [10] John D’Emilio, ‘Capitalism and Gay Identity’, in The Gay and Lesbian Studies Reader, eds. Michele Aina, Barale, David M. Halperin, and Henry Abelove (New York: Routledge, 1993), pp. 467–476. [11] Lisa Duggan, ‘The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism,’ in Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics, eds. Dana D. Nelson and Russ Castronovo (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2002), pp. 175–194. [12] D’Emilio, p. 470. [13] Judith Butler, Preface, Gender Trouble, 2nd edn. (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. vii–viii. [14] Butler, p. viii. [15] Judith Butler, Precarious Life (London: Verso, 2004) and Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015). [16] Emily Jones, ‘Feminist Technologies and Post-Capitalism: Defining and Reflecting Upon Xenofeminism,’ Feminist Review, Vol. 123, Issue. 1 (2019), p. 127. [17] Laboria Cuboniks, The Xenofeminist Manifesto (London: Verso, 2018), p. 55. [18] Cuboniks, p. 17. 21/6/2021 Fascism as a recurring possibility: Zeev Sternhell, the anti-Enlightenment, and the politics of an intellectual history of modernityRead Now by Tommaso Giordani

Examining the development of Zeev Sternhell’s work yields a precise impression: that of a movement from the particular to the general, from an intellectual history rooted in precise contexts to increasingly broad studies dealing with larger and less narrowly contextualised traditions of thought.

His first monograph, published in 1972, was titled Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français and examined the role of Barrès in transforming a French nationalism which was originally “Jacobin, open, grounded in the doctrine of natural rights” into an “organic nationalism, postulating a physiological determinism”.[1] In the decade between 1978 and 1989, Sternhell publishes the three works which created his reputation as one of the world’s most important historians of fascism: Ni droite ni gauche, La droite révolutionnaire, and Naissance de l’idéologie fasciste. Though still maintaining a focus on France, these studies—especially the last one—cannot be reduced to contributions to French history. They are instead an attempt to outline a theory of fascism centred on the importance of the ideological element, something which naturally brought the Israeli historian and his collaborators beyond the borders of the hexagon. Following this interpretative line, we can identify a third phase of Sternhell’s work starting from the 1996 collective volume The intellectual revolt against liberal democracy. Having first moved beyond the examination of French nationalism towards a more general theory of fascism, in this third phase Sternhell leaves the question of fascist ideology behind, embedding it in a larger narrative embracing the last three centuries of European intellectual history and revolving around the dichotomy between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment ideas. The high point is represented by his last and most ambitious study, Les Anti-Lumières, in which the Israeli historian traces the development of what he calls a “different modernity”, consisting in a “comprehensive revolt against the Enlightenment’s fundamental views”.[2] I. There is obviously a great deal of truth in this way of reading the Israeli historian’s trajectory, especially given the substantial growth of the materials treated and the enlargement of both chronology and geography. And yet, there is an important way in which this reading is wrong, namely if it is taken to claim that the large, meta-historical categories of “Enlightenment” and “Anti-Enlightenment” are inductive generalisations, synthesising decades of work in intellectual history and emerging from Sternhell’s previous studies. A summary look at Sternhell first book reveals, instead, that these categories have informed his work since the beginning. Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français is, as we have pointed out, not a simple intellectual biography, but a work which sees the significance of Barrès through the wider lens of a study of the transformation of French nationalism. Upon closer inspection, however, it is clear that even the framework of French nationalism is a very reductive description of Sternhell’s perspective, for it is a nationalism which is embedded in a wider current of ideas, both spatially and temporally. Spatially, Barrès participates in a tradition of thought which is continental. He is cast by Sternhell much more as a European than as a Frenchman. Barrès is “the child of his century: Baudelaire and Wagner fascinate him, he calls himself—and is—a disciple of Taine and Renan; he has read Nietzsche, Gobineau, and Dostoevsky. For his first trilogy, he claims to have been inspired by Schopenhauer, by Fichte, and by Hartmann”.[3] Temporally, this continental tradition to which Barrès belongs is cast as deploying itself over a broad chronology, as can be evinced by Sternhell’s insistence on its similarities with “another movement of revolt against the status quo: pre-1830, post-revolutionary romanticism”.[4] Without denying the decisive role of European fin de siècle culture, Sternhell finds common traits between this “neo-romanticism” and the older movement. In both cases, we have a “resurgence of irrational values”, the “cult of sentiment and instinct” and, finally, “the substitution of the ‘organic’ explanation of the world to the ‘mechanical’ one”.[5] Even if the connections are merely sketched, it is clear that the temporality in which Sternhell places his object is that of modernity. Barrès, in other words, is significant not just as a French nationalist, but as a member of a tradition marked by the “systematic rejection of the values inherited from the eighteenth century and from the French Revolution”.[6] Granted, the term “Anti-Enlightenment” does not appear in this work, and comparison of this initial sketch of the tradition with later versions yields some differences, such as a greater role he later ascribes to German and Italian historicism, as well as a tendency to read this current of ideas in an increasingly static and monolithic way. And yet, beyond these small differences, substantial similarities emerge: the broad chronology, the continental extension, and the dichotomous division of the last two centuries of European intellectual history into the two opposing camps of the Enlightenment and its enemies. II. This dichotomy informs virtually the entirety of Sternhell’s works in the history of political ideas. We see it at work in his trilogy on fascist ideology, and it is subtly yet unmistakeably active in his analysis of Zionism, in which Jewish nationalism is characterised, inter alia, as a “Herderian” response to the “challenge of emancipation”.[7] Underlying historical enquiry on particular political ideologies, in other words, is a theory of European modernity revolving around the opposition between what Sternhell came to label the universalistic “Franco-Kantian Enlightenment” and its particularistic opponents. Methodologically, the advantages of this approach are many: it allows the writing of a profoundly diachronic history of ideas, capable of embracing a multitude of contexts and spaces, and in theory able to trace the evolution of traditions of thought without losing sight of the underlying continuities. At the same time, various critics have underlined its limits. Sternhell has been accused of not having learnt the lessons of postmodernism, and of reconstructing the intellectual history of European modernity in the form of a “Manichean struggle” between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment.[8] General accusations of Manicheanism, approximation, and teleology are, in fact, amongst the most common directed against Sternhell. Shlomo Sand gives a more precise way to consider the limits of this approach, identifying the problem in Sternhell’s use of “narrow, static, unhistorical definitions”, that is, of meta-historical categories.[9] Here we come to the crux of the question: Sternhell’s way of proceeding is indeed marked by the use of categories of analysis which transcend the contexts in which historical actors developed their thought. Is this, however, enough to methodologically invalidate his analysis? The use of categories transcending narrow historical contextualisation is a necessity for any work with diachronic ambitions. Tracing the development of any tradition of thought over time, in other words, implies the use of descriptions and definitions which would have appeared bizarre to the thinkers of the time. The employment of a meta-language, and the anachronism, teleology, and de-contextualisation that come with it, are, to a point, a necessity of any genealogy, of any historical enquiry which aims to do more than simply take a synchronic snapshot of the past. Therefore, it seems incorrect to identify the problem in the mere use of categories such as Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment. The problem lies not in the mere presence of these meta-historical tools of analysis, but, rather, in the way in which Sternhell has come to employ them over time. As we have seen, in Maurice Barrès the anti-Enlightenment tradition was sketched with a certain nuance, insisting on its internal transformations over time, and paying attention to the crucial distinction between the work of an individual and its reception. Over time, however, much of this nuance disappears, and passages from his later works do seem, at times, to interpret two centuries of European intellectual history through the prism of what is, after all, a not too dynamic dichotomy between French universalistic culture and German romantic particularism. III. Take Sternhell’s analysis of Georges Sorel’s revision of Marxism at the beginning of the 20th century, for example. For the Israeli historian, it constitutes a crucial step towards the creation of fascist ideology. According to him, the key element of Sorelian revisionism is the destruction of the connection between the industrial working class and the revolution, something capable of altering “Marxism to such an extent that it immediately transformed it into a neutral weapon of war that could be used against the bourgeois order not only by the proletariat but by society as a whole”.[10] Sorelian revisionism thus consists in the removal of Marxian categories of analysis based on social antagonisms grounded in the positioning in the productive structure of society, which are then replaced by antagonisms grounded in an opposition to the decadence of bourgeois civilisation. As Sternhell puts it, “history, for Sorel, was finally not so much a chronicle of class warfare as an endless struggle against decadence”.[11] It follows that if the proletariat is unable to fulfil its struggle against bourgeois decadence, there is no reason why another historical agent, such as the national community, should not engage in the same struggle. The result is fascism. The problem with this reading is that, despite its apparent plausibility, it is historically inaccurate. Real Sorelian revisionism consists in a number of texts published in the 1890s in which the main thrust is epistemological and social scientific more than political. Its consequences are opposite to those drawn by Sternhell. Animated by the desire “show to sceptics that… socialism is worthy of belonging to the modern scientific movement”, Sorelian revisionism revolved around three main points: (1) the refusal of historical determinism; (2) the rejection of economic determinism; and consequently, (3) a vision of Marxism not as a predictive social science but as the intellectual articulation of the historical experience of the workers’ movement.[12] Even if this revisionism is much more concerned with Marxism as a social science than with Marxism as a political project, its political uptake is not the breaking of the connection between proletariat and revolution, but its strengthening. A Marxism which renounces its predictive capacity and the very idea of a necessary historical development cannot but evolve into what Sorel later called a “theory of the proletariat”. The removal of historical necessity means that the transition to socialism can only be yielded by the agency of the revolutionary subject—the proletariat. It should thus not be surprising that, as early as 1898, Sorel insists on working class autonomy, arguing that “the entire future of socialism resides in the autonomous development workers’ unions”.[13] The revision of Marxism does not exhaust Sorel’s production and there are parts of his trajectory, and of those of some of his disciples, which are more in line with Sternhell’s analysis. And yet, the fact remains that this analysis completely overlooks contexts which are crucial to Sorelian revisionism, resulting in an historically inaccurate picture. The point is not merely to underline the many substantial imprecisions which characterise Sternhell’s reading of Sorelian revisionism, but to emphasise how these misreadings derive directly from the indiscriminate use of the abovementioned meta-historical categories. “Marxism” writes Sternhell “was a system of ideas still deeply rooted in the philosophy of the eighteenth century. Sorelian revisionism replaced the rationalist, Hegelian foundations of Marxism with Le Bon’s new vision of human nature, with the anti-Cartesianism of Bergson, with the Nietzschean cult of revolt, and with Pareto’s most recent discoveries in political sociology”.[14] But is it plausible to speak of a rejection of Hegel for someone so profoundly influenced by Antonio Labriola, who represented one of Europe’s main Hegelian traditions? Is it correct to speak of the “Nietzschean cult of revolt” for a figure who wrote over 600 texts and yet discusses Nietzsche virtually only in a handful of pages in the Reflections on violence? Is it historically acceptable to suggest proximity to Paretian elitism for a political thinker who wrote vitriolic pages against the leadership of French socialism by bourgeois intellectuals? These misreadings derive from the fact that Sternhell’s dualistic approach, if taken rigidly, cannot make space for Sorelian revisionism, for that would imply accepting the possibility of a Marxism capable of incorporating elements of romanticism without ipso facto becoming a sworn enemy of the Enlightenment. But Marxism, for Sternhell, is “rooted in the philosophy of the eighteenth century”, and any deviation from this particular philosophical outlook is to be classified as anti-Enlightenment thought. Strictly speaking, for Sternhell, Sorelian revisionism is a betrayal. But here are the limits of Sternhell’s rigid application of his categories, limits which emerge not only in relation to Sorel, but also to Marxism more in general. Marxism is, from its beginnings, a politico-philosophical tradition which is transversal to the dichotomy between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment. The mere suggestion of reading a tradition derived from Hegel and Marx as in opposition to German romanticism shows the dangers of overreliance on these categories. The appropriate historical context for understanding Sorelian revisionism is the battle, internal to Marxism, between positivistic and humanistic interpretations of Marx’s work. Against Sorel’s insistence on the impossibility of historical laws there is Lafargue who advocates their existence; against Antonio Labriola who struggles to free historical materialism from positivism there is Enrico Ferri who goes in the opposite direction. To miss this transversality of the Marxist tradition cannot but yield serious mistakes. How would Sternhell judge Gramsci’s claim that Marxism is “the continuation of German and Italian idealism, which in Marx had been contaminated by naturalistic and positivistic incrustations”? Would he see a voluntaristic cult of revolt in the affirmation that “the main determinant of history is not lifeless economics, but man”?[15] IV. Why, in the face of much criticism, did Sternhell never even go close to admitting the risks of a certain way of employing an approach based on meta-historical categories? Why did he not only stick with it, but began using it in an increasingly rigid and passionate manner? To answer these questions, a preliminary point must be clarified. If the Enlighenment/anti-Enlightenment dualism is the conceptual centre of Sternhell’s work, its existential core is the question of fascism. Orphaned and turned refugee by anti-Semitic violence in his native Poland during World War II, Sternhell has always been very clear on the fact that for him the study of fascism went far beyond purely academic interest. Anyone who has read the pages he has written will be aware of the urgency of his prose, of the passionate tone of warning which permeates most of them, especially those on fascism. “Thinking about fascism” he wrote in 2008 “is not a reflection on a regime or a movement, but a reflection on the risks that might be involved for a whole civilisation when it rejects the notion of universal values, when it substitutes historical relativism for universalism, and substitutes various communitarian values for the autonomy of the individual”.[16] Aside from clarifying the relationship between fascism and anti-Enlightenment in Sternhell’s thought—with the former political option becoming possible only in an environment in which the latter’s ideas are present—this quotation sheds much light on Sternhell’s insistence on the Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment duality. To frame fascism as a political possibility enabled by the existence of certain anti-Enlightenment ideas means adopting a view of fascism as a recurring possibility of modernity. Fascism is thus not an abstract and a-historical ideal type, but neither is it an historical particularity inextricably linked to the specific, and unrepeatable, conditions of interwar Europe. To embed fascism in a theory of modernity, in other words, allows one to see it as a living political culture, perhaps at times dormant, but constantly capable of making the leap from cultural contestation to political project, at least as long as the particularistic ideas of the “alternative modernity” of the anti-Enlightenment continue to inform European intellectual life. Sternhell’s dismissal of the decisive role of World War I and his insistence that the fascist synthesis was already achieved in the belle époque substantiate this reading. The Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment framing, in short, stems from the fiercely held conviction that fascism is not a thing of the past, but of the present. It is a framing, thus, that at once emerges from the need for public engagement and simultaneously enables a mode of public intervention which could not as easily be sustained through a narrower contextualism or a taxonomical approach. Recent years have brought, together with the electoral victories of right-wing forces in Europe and the United States, a flurry of analyses on the return of fascism. Whether through taxonomies, historical parallels between the present and the interwar period, or analyses of fascist mentality, this literature has been animated by the same conviction that has long animated Zeev Sternhell’s work: that fascism is not a thing of the past. Eschewing these strategies, however, Sternhell has long pioneered a different way of thinking about fascism: not an historical particularity, not a mentality, not a list of criteria that regimes must possess, but instead a constant potentiality of European modernity, embedded in two centuries of anti-Enlightenment thought. By way of conclusion, a tentative answer to the obvious question: from where does Sternhell’s conviction that fascism is always possible emerge? It is true that the defeat of 1945 has not been the historical caesura one unreflectively imagines, and that fascism has continued to exist, in less ideologically assertive forms, in many countries of southern Europe. At the same time, before the recent, possibly short-lived, resurgence of the fascist spectre, academic analyses of fascism were rarely animated by this urgent conviction of its relevance. The answer to this conundrum is to be found in Sternhell’s political engagement in his country, Israel. In March 1978, together with other reservists of the Israeli army, Sternhell signed an open letter to then Prime Minister Menachem Begin, warning that a policy “which prefers settlements beyond the Green Line to terminating the historic conflict” was a dangerous one, which could “harm the Jewish-democratic character of the state”.[17] The letter established the organisation Peace Now, in which Sternhell continued to be active for the rest of his life. Over the years, the evolution of the political situation made the positions Sternhell supported increasingly minoritarian. But the Israeli historian did not back down. On the contrary, he continued to put forward his positions. This earned him a pipe bomb attack at his home in Jerusalem in 2008, from which he emerged substantially unscathed. Flyers offering over 1 million shekels to whoever killed a member of Peace Now found near his home left little doubt as to the motivations behind it. After Benjamin Netanyahu became prime minister in 2009, Sternhell became increasingly vocal, denouncing what he saw as a dangerous evolution of Israeli society. In his many public interventions, he uses the language with which we have been dealing here, that of the anti-Enlightenment. He saw the rise of the Israeli right as that of a “power-driven national movement, negating human rights, and rejecting universal rights, liberalism and democracy”.[18] In a 2014 interview in which he denounced signs of fascism in Israeli society, he framed that political option in familiar terms: as a “war against enlightenment and against universal values”.[19] In 2013, he was called as an expert witness in a defamation case put forward by the nationalist association Im Tirzu against some activists who had labelled it as fascist. In an exchange with Im Tirzu’s lawyer, we see, again, the same language: “…they are not conservatives, but revolutionary conservatives. What they seek is a cultural revolution. ‘Neo-Zionism’ as they define it is an anti-utilitarian, anti-western, anti-rational cultural revolution.”[20] Examples of this kind could be multiplied, but the point should by now be clear. Certain methodological options may seem puzzling when judged uniquely by the standards of academic practice, but the rationale for their employment may become more understandable when they are seen as connected to a concrete historical situation. The Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment dichotomy, with all the limits that Sternhell’s passionate use involved, is one such case: it must, at least partially, be seen as emerging from the imperative of engagement. Still, Sternhell’s historical works are not political pamphlets. Even if sometimes they possess the urgent tone of that genre of writing, they remain contributions to the study of European intellectual history, and should be judged also according to those standards. And yet, the separation of these two layers, engagement and scholarship, is not easy and, to a point, not desirable. To effect this separation would be to misunderstand the work of a scholar for whom the two were intertwined. As he argued in the most articulate defence of his method, “through contextualism, particularism, and linguistic relativism, in concentrating on what is specific and unique and denying the universal, one necessarily finds oneself on the side of anti-humanism and historical relativism”.[21] The author would like to thank Or Rosenboim for discussions on the Israeli context and for help with translations from Hebrew. All other translations from French and Italian sources are the author's. Research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under Grant Agreement No. 757873 (project BETWEEN THE TIMES). [1] Zeev Sternhell, Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français [1972], 3rd ed. (Paris: Fayard, 2016), 251. [2] Zeev Sternhell, The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition, trans. David Maisel (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 1. [3]Sternhell, Maurice Barrès, 56. [4] Ibid., 42. [5] Ibid., 43. [6] Ibid., 41. [7] Zeev Sternhell, The Founding Myths of Israel. Nationalism, Socialism, and the Making of the Jewish State, trans. David Maisel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 12. [8] David D. Roberts, ‘How not to think about Fascism and ideology, intellectual antecedents and historical meaning’, Journal of Contemporary History 35, no. 2 (2000): 189. [9] Shlomo Sand, ‘L’idéologie Fasciste en France’, L’Esprit, September 1983, 159. [10] Zeev Sternhell, Maia Asheri, and Mario Sznajder, The Birth of Fascist Ideology. From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution., trans. David Maisel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 37. [11] Ibid., 38 [12] Sorel to Croce, 20/12/1895, in Georges Sorel, ‘Lettere di Georges Sorel a Benedetto Croce’, La Critica 25 (1927): 38. [13] Georges Sorel, ‘L’avenir socialiste des syndicats’, L’humanité Nouvelle 2 (1898): 445. [14] Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology, 24. [15] Antonio Gramsci, ‘La rivoluzione contro il Capitale’, Avanti! 24 November 1917. [16] Zeev Sternhell, ‘How to Think about Fascism and Its Ideology’, Constellations 15, no. 3 (2008): 280. [17] Open letter to Prime Minister Menachem Begin, March 1978, https://peacenow.org/entry.php?id=2230#.YK5yjKGEY2w [18] Zeev Sternhell “Does Israel still need democracy”, Haaretz, 17 November 2011 [19] Gidi Weitz, ‘Signs of fascism in Israel reached new peak during Gaza op, says renowned scholar’, Haaretz, 13 August 2014. [20] Oren Persico, “Analyzing with an ax”, Ha-ain ha-shvi’it, 12 May 2013, https://www.the7eye.org.il/62652 [21] Sternhell, The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition, 35. 14/6/2021 Ideology, Transformative Constitutionalism, and Science-Fiction: An Interview with Gautam BhatiaRead Now by Udit Bhatia and Bruno Leipold

Udit Bhatia: It might be useful for our readers if you could start off by saying what the idea of transformative constitution is and what work it does in your reading of the Indian constitution.

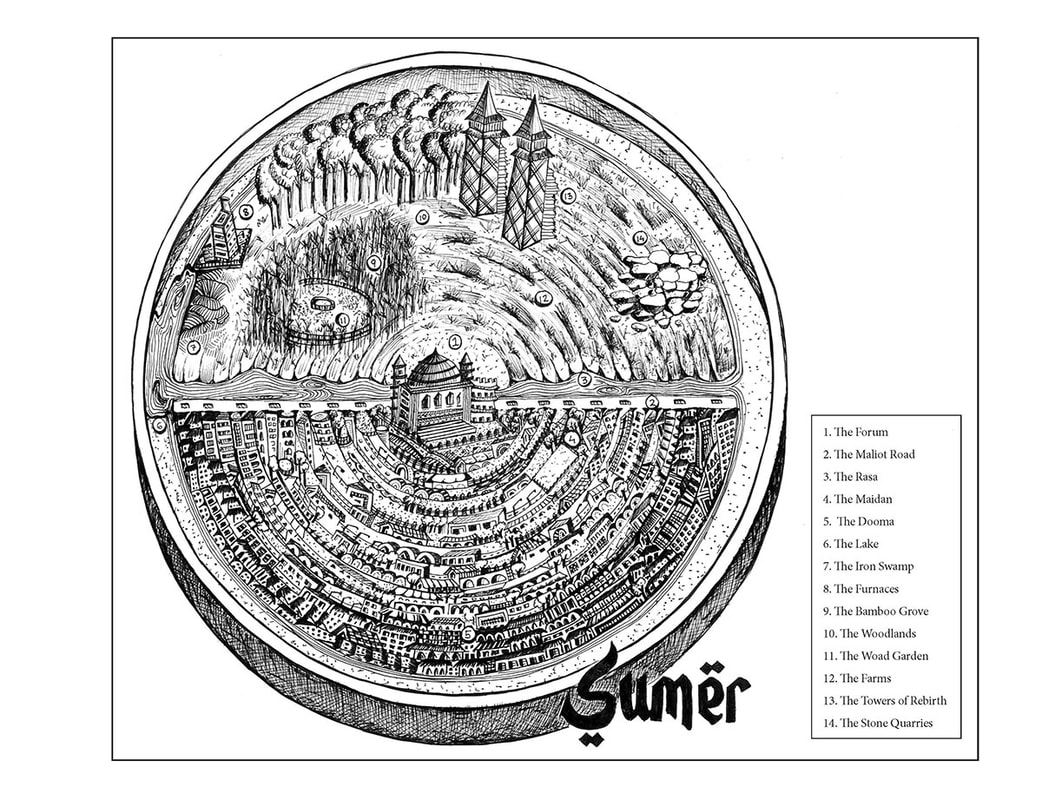

Gautam Bhatia: The term transformative constitutionalism or transformative constitution originated in post-apartheid South Africa and it had a, it is a contested term. My understanding of it is that there are basically two things about it. First, that it's distinctively post-liberal in its approach to constitutionalism. There was a certain classic understanding of constitutions as being about limiting state power. That is an understanding that comes from the American Constitution that has had a disproportionate influence on constitutionalism across time and across the world. Transformative constitutionalism is post-liberal in the sense that it understands the role of a Constitution to be more than containing the state and it actually involves directing the state towards achieving certain social goals. Another really fundamental tenet of liberal ideology is the idea of neutrality. For example, John Rawls’s ‘right over the good’, where we can disagree over goals but there are certain rights- based principles that are non-negotiable. But transformative constitutionalism specifically says that there’s a certain vision of society we're trying to get towards. In that sense, it’s also post-liberal that you could call it perfectionist again to use the term from analytical philosophy. But it has a certain blueprint of the society that it envisages as being the good society and it sees constitutions and constitutionalism as vehicles for getting there. And then it also calls for changing legal culture, so it's not just what a constitution can do. To make the constitution do that you have to then alter the way people argue in court, the things that courts can do and just the structure of legal argument and legal culture. So the original article by Karl Klare, a labour lawyer talked about both these things, and often a bit about legal culture is forgotten and in my book, the term transformative constitutionalism broadly does something similar in the sense that it specifically talks about the Indian Constitution as being post-liberal in the sense that it was understood to be an intervention, both with respect to containing state power and providing political and civil rights and transforming subjects into citizens. But also, it was meant to bring about a far-reaching transformation in Indian society and, specifically, tackling private power. So power that exercise through institutions, whether they are social institutions like caste or economic institutions like the marketplace or cultural institutions, various religions. The Constitution, constitutional law, ideas of rights were envisioned as applying to what we classically understand as the private domain. In that sense the Indian constitution was meant to challenge the ideology, so to say, of the public-private divide. That's how I understand the transformative constitution in the Indian context. UB: Perfect, thanks Gautam! I think one of the things that struck me was how much of the work of excavating these transformative elements happens through your reading of dissenting judgments. Now someone might look at that and think ‘well, great, there’re all these resources you’ve managed to identify in India’s legal history’. But on the other hand, one might think ‘why is this all just dissent—that’s worrying!’. So could you say a bit more about what's going on here? GB: Historically the constitution's transformative impulses have been submerged by the adjudicatory body that is charged with being the final word on the Constitution, which is the Supreme Court of India. The dominant interpretation that the Indian Supreme Court has placed upon the Constitution and its provisions has been a conservative one. The transformative interpretation exists, and I use Edward Said’s idea of the ‘contrapuntal canon’. So there is a canon—there is the Indian constitutional canon of judgments which, despite a contrary long-standing public perception, encouraged by the Court, and by various scholars, is conservative. But then there are these dissenting judgments, some High Court documents, and the odd majority judgements as well. If you read these against the grain, in a contrapuntal way, you can excavate the transformative impulses that are there in the Constitution’s text and structure. UB: As one reads the book, you get an idea of the substantive transformative elements in the constitution—especially their engagement with private regimes of power, or their focus on community ties that can infringe individual autonomy in all sorts of ways. But the other side of this story might be the conservatism of the constitutional text in procedural terms: the fact that the constitution set up elitist representative institutions with few opportunities for contestation by ordinary citizens. So, in a way, the transformative constitution was always likely to end up as a dissenting note. I wonder how wedded you are to the idea of transformative constitutionalism through the constitutional text. GB: The great thing about texts is that they’re always open to interpretation. Something like a constitutional text, given the complicated social histories leading up to the framing of the Constitution, given that constitutional texts are invariably in the language of the abstract principle and not concrete commitments, given that a constitutional text is always open to a diverse range of interpretation—all this makes the interpreters task to bring together different elements, text, history, structure and so on—and fashion the most persuasive reading possible of the constitutional document and I think it is eminently possible to fashion a conservative reading of the document, given its history, and given the text. And that project hasn't happened yet, in my view, although some of H.M. Seervai’s work gestures towards that—though I wouldn't call it necessarily a right-wing interpretation. It is conservative in just placing the boundaries of interpretation as being contained by the text and not beyond that. So it is an essentially a legally conservative reading that he provides, although ironically It is far more rights-protective than a lot of the supreme court's own judgments. But the task that I see for myself as the interpreter is to use these materials that are in existence to fashion a persuasive transformative reading of the text of the constitutional law. I don't think there is a view from nowhere, and there can’t be a non-engaged engaged standpoint. And my standpoint is from the internal perspective, which is that of a lawyer who works with the Constitution and who believes that there’s a set of important progressive goals that a Constitution is a vehicle towards achieving. It‘s a perspective which says that the Indian Constitution can and should be persuasively interpreted, so that it leads us towards those goals. I don't claim for myself the standpoint of an objective interpreter. I don't think there is any such standpoint but I am a participant and I'm saying ‘look, this is my argument and see if it's a good argument’. If somebody else has a better conservative argument for the Constitution, then fair enough. If that persuades you, as the public, then that’s perfectly fine. This is my argument I am placing before you and I hope that it persuades you. UB: You’ve made it quite clear in the book that you’re telling us only the judicial side of the story of transformative constitutionalism in India, and that’s not the whole story. But could you say more about the trajectory of this idea outside the courts? GB: I would recommend Rohit De’s book “A People's Constitution” that deals with the first decade after independence, throws light on how ordinary Indians understood the Constitution, leveraged it, and used it as a tool to expand their rights. And they weren't always successful but It really shows you how the Constitution became an idiom for language outside of the courts. In the last few years—and this is a really cliched example by now—but the CAA protests are a really good example of the constitutional idiom going beyond the courts. I think what was really interesting about the CAA protests was that the protesters were really clear about the fact that they were advancing an understanding of the Constitution that derived its legitimacy and validity, not in the hope that it would be one day accepted by the Supreme Court, but by the force of argument alone outside of the Court. They fashioned a certain reading of the preamble of the Constitution, a certain reading of Article 14, the equality clause, and they were very careful to decentre the Supreme Court. If you look at the history of those protests and how the Constitution was used, it was always a reliance upon the document and there was no reference to the fact that there were pending constitutional challenges in the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court might or might not vindicate this understanding. It was a reading of the construction that stood on its own legs. That is one of the I think standout examples of transformative constitutionalism that did not rely upon the court. If you look at a lot of work being done in Assam right now, in the aftermath of the NRC by lawyers like Aman Wadud, you find that they're setting up these Constitution centres in various places, explaining the Constitution. Again, they’re doing this without necessarily anchoring it to Supreme Court’s understandings of the constitution. UB: Over the last few years, commentators like yourself have noted the rise of authoritarianism in India—and the courts have not been immune from this. You’ve expressed concerns about the extent to which one can continue pretending the judiciary operates along the line of rule of law. According to you, what’s the role of the lawyer in such circumstances? GB: I think the role of the lawyer is a very difficult one, especially when it involves issues like the CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act), Kashmir, Aadhar—basically, issues involving state power and the constitution. You need a set of lawyers who will represent a client’s case as if everything was completely normal, as if this were a functioning democracy, with independent institutions. You need one set of lawyers, in my view, who will do that because that's work that needs doing. You also need a set of lawyers, whose knowledge of the practice of lawyering and judging, which is an internal perspective—because they've been in court—and no matter how careful an external analysis might be given, given the number of context-specific practices that can have developed over the years, there are things a lawyer sees just by virtue of being in court that are impossible to see from outside. So I think you also need a set of lawyers who draw upon that experience to mount a critique of the Court and the role the Court in checking or failing to check authoritarian tendencies and centralisation and so on. I think that you need both kinds because as long as courts exists as centres of power, you need people who will speak in the language of the institution. But if that is the only kind of speaker that there is, the perception will remain of a well-functioning institution. So you will also need to have people who will critique the functioning of the institution. Yet, if you only have people who do that then there'll be nobody left to make the case inside the court. You need a combination of both things, I think. It's every lawyer’s decision, a question of conscience, what role you want to occupy. You have to have one of the two roles, assuming you have the privilege, the resources, and the luxury of choosing. I think one of those two roles is important when the situation is one in which authoritarian tendencies are overwhelming institutions. Bruno Leipold: Oh, maybe I could jump in quickly and ask one question about the book. One thing that struck me is that you quite extensively draw on the idea of republican freedom. I would be quite interested to hear more the way in which debates about republican freedom were helpful to formulating your arguments about transformative constitutionalism? UB: It also seemed that this was also one of the shorter chapters, and the sense I was getting was this isn’t something that's come up much with the court—except in a judgment where exploitative economic conditions for workers is interpreted as something like forced labour. Could you give us a sense of the judiciary’s further engagement with this idea? Has this notion come up again in other cases? GB: Yeah so the second question is a shorter one so in brief, no, the PUDR judgement—which held that the right against forced labour includes a right to a minimum wage—is the only Supreme Court judgement to have given that interpretation to article 23. You find one High Court judgment 1994 in Allahabad that said something similar. But that's it, and I think it's just because the radical implications of that argument. So, after the PUDR judgement, there were a couple of Supreme Court judgements where people tried to rely upon PUDR as precedent and the court just shut them down and distinguished the case, and you know basically just kind of buried that that judgment. And I think it's obvious why because its just the implications are radical it, it would mean basically an anti-capitalist reading of the Constitution, which our courts or any set of courts anywhere are not willing to sanction. As far as the role of republicanism goes, I think that the insight that republicanism provides for that kind of a reading of the forced labour clause is the focus on freedom as non-domination. Now classical republican theorists still locate the source of domination in a personalised manner, so you still need an identifiable person to pin that dominating power on. Which, of course, is not feasible and that's where workplace republicanism comes in, that is expressed I think most powerfully in writings of scholars like Corey Robin and William Claire Roberts and so on, is a depersonalisation and institutional or structural view of domination and of power. So, if you just look at the classical understanding of fundamental rights and why they were applicable against the state, the idea was that the state has the has a monopoly over power. Right, and this idea of the monopoly then kind of runs through constitutionalism so when you want to affix liability for rights violations on a private party, a question that courts often ask is that does this private party exercise the monopoly over an important good or service, so if, for example, a body has monopoly over all the water supply, in an area or electricity in an area and it's discriminating and not say providing water to people of certain religion right, then the court can often argue that okay, because of its monopoly this private body has a state-like function, and therefore the constitutional rights provisions apply to it and therefore you know we are you know stopping this from going forward. What that ignores is that you don't need to have a monopoly, but it may still be impossible to exit from an institution—which is the classic you know the whole point about the workplace and about labour, the labour market is that no individual capitalist has a monopoly, in fact, you know the capitalist is as constrained by the demands of capitalism, as the worker, it is the capitalist that has to constantly ensure that you know they're cutting costs and increasing profits because otherwise they’ll get out of business, and that we know that going back to Marx. So it's not it's not an individual capitalist who is a monopolist but it is the kind of a structure or the institution of the labour market that’s exercising that power through individual capitalists. So workplace republicanism I think gives us a way or a method to frame that insight and constitutional language and to say that therefore workers have constitutional rights against their bosses, even though a boss, is not the state. UB: It's interesting you bring this up because there's so much in the book on private regimes of power, and that the book ends on the dangers of Adhaar (India’s biometric identity system). And it strikes me that one of the risks of Adhaar is very much it becoming something that private players start to emphasise; for instance, by linking private services to the Aadhar system. Is there a relationship of complicity between these private regimes of power and state power? GB: Yeah, so I think in the Aadhaar case private regimes are operating under delegated powers from the states because Aadhaar is ultimately a nationwide centralised biometric identification system where the centralisation is by the state; the UIDAI is a state body and to the extent that private players can use the database, they do it on sufferance under Section 57 which was struck down, but then, of course pretty shamelessly reenacted by the government. So in the Aadhaar case it's actually the state power that’s being parceled out to private parties now, of course, I mean there is an argument to be made that you know the State itself is a terrain of class conflict, and so, to what extent is actually distinct from private parties? So I think that’s a political theory argument, but in terms of at least Constitutionalism and the law, the Adhaar cases I think straightforwardly involves state power and private parties do have and continue to weaponise the database for you know data gathering, data collection and use of data and denial of service and so on, but that, but their authority still flows from a law whereas the argument on private regimes was more that if you have something like you know caste enforced you know, social boycotts, it’s not really relying on the state in at least formal terms. Of course, I mean there's a long argumentative tradition coming from the legal realists in the US, that ultimately the legal regime is gapless so you know I mean, even if there is no formal law, the state by its inaction is allowing things to happen so there's always the state involved and in that sense there's no real private action that is not either sanctioned by or the sufferance of the state. So you go down that route, then of course I mean the States always involved, you know in every private action or if you don't go down that route, then you know the distinction between state sanctioned law, as in the Adhaar case and the case of caste boycott, cases where private employers have not been paying a minimum wage, and so on. UB: Bruno I might let you take over now and may come back to them after you're done depending how much energy we leave him with. BL: So let’s turn to the literary side of things. I read The Wall in December and I want to start by saying what a fantastic achievement it is. There’s not many people in the world that can write both constitutional theory and beautiful, engaging science fiction! What I really loved about the book, and I think quite a few reviews of the book have picked up on this, is how impressive the level of world building is. You set out everything from the city’s origin myths, its constitutional history, its religions, its literary culture—it’s all there. Perhaps I could start by asking if you could give our readers a sense of what the book is about and also what led you to write it? Its, of course, quite a gear shift from your day job as a constitutional theorist! GB: Thank you! I’ll start with the second question. So while people might know me from my day job as a lawyer, I have actually been a science fiction fan since the age of 10 when my parents got me a copy of the Hobbit and then of Asimov's Foundation. Of course, the genre has moved beyond that now, but that was my introduction. So since the age of 10 I’ve been a huge fan and my teenage years were full of handwriting science fiction novels—pretty bad novels obviously! And then in 2015 I joined Strange Horizons the science fiction magazine as a non-fiction editor. I've been involved with them for the last five years now, five or six years. So my association with science fiction and fantasy, is something that is much older than my association with law and you know it's always been there and this novel actually began life back in 2008 when I was in college and I didn't at all know that I would go on to become you know, a full time lawyer and my day job or even stay with law, so its origins actually go back to even before I really got into law as a profession. As to what the book’s about to put it simply it's a speculative fiction somewhere at the borders of science fiction and fantasy. It is set in a city that is enclosed completely within a very high wall that nobody has crossed in living memory. There is abundant water (the source of which is unknown), but every other resource is scarce. But that scarcity is not an ideological imposition, it's actually physically scarce, and therefore, the food and the wood and the material required for clothes and so on are all actually limited quantities. And that influences the social, economic and cultural structures that are present in the city. It's not a dystopia because there is just about enough there for everyone to be able to live a life that is not a life of squalor or a life of want so it’s not a dystopic city, but it is stasis, and it is contained. And the core plot point is that there are a group of people who do want to find a way beyond the wall and know what lies beyond and the book is about their efforts to do that, in the face of hostility indifference and so on. BL: These are the Young Tarafians, right? Do you want to say something about the other ideological and political factions in the book and the underlying political structure? GB: At the broad level there are three factions in the city. One is the Governing Council of the city of Sumer, called the Council, or the Elders, which are a group of 300 people who govern the city. That political arrangement doesn't really borrow from any one thinker or historical example, but is most closely inspired by James Harrington the 17th century English philosopher, because of his idea of 300 people and how the balance between propertied and non-propertied classes is achieved. One interesting thing, for me at least, is that in Sumer they do democracy, but in a slightly different way, in that they are not elected, they are self-appointed, but every decision that they take is put to a referendum in the city. So although it's not democracy at the starting point as there are no elections, but it is a democracy at the at the end point, in that their decisions have to be put to a popular vote. However, there is one catch, which is that if you want to actually alter the property relations or underlying constitutional arrangements you have to have a two thirds majority. That’s an idea taken from Pinochet’s military constitution that enshrined neoliberalism, and that also gives you a clue about some of the underlying ideological debates in the book. So the Elders or the Council are the secular governing body of the city, and then there are the Shoortans—the religious group. That's drawn from the idea that if you have a city within a wall and its very clear that the wall is not natural, it was built by someone. And that someone gave to the citizens, the exact amount of resources in exactly the right balance to enable them to survive. So, clearly there is a governing intelligence or a governing hand behind this, which would lead to all kinds of duelling origin stories that are born from the realisation that there had to be a creator. So Shoortans have a set of beliefs about the creation and that the purpose of the wall is to keep them safe and therefore it should not be crossed. The final faction are the scientists, who are also called the Select, whose job it is to ensure that the city continues to run and to survive. They ensure that the proportions of the resources remain just right and that consumption remains at a level at which everyone can continue to survive. Because if you're living in a semi-closed system then a small change can lead to widespread devastation. So the scientist’s role is to ensure that things are kept on track and they're kind of exist with the other factions in a somewhat unstable equilibrium with each other, where you know there is a division of power, but it's a little uneasy and unstable. BL: Between these factions there's also ideological disagreement over what one of the central concepts of Sumer really means, that is the concept of ‘Smara’. GB: The idea of Smara is a bit of a cheat on my part because an Indian reader would kind of guess it’s meaning because it does draw from an Indian word. I'm sure when Udit reads the book when he sees the word Smara, he would have a rough idea of where that thought line is going but a non-Indian reader might not immediately. Smara, broadly is this idea of yearning or the yearning for a world without the wall, although what exactly it means is contested. It's a feeling that everyone has experienced, in the sense that everyone at certain times has this feeling of being enclosed, of being trapped, this yearning to know what's beyond that. To be able to see a world in which there is a horizon, because they also don't have a word for the horizon, but to see a world where actually you know everything you see isn't cut off by the wall. For some, this is actually a reason to go beyond the wall, to find out what's beyond that, so that they can put an end to this constant yearning and to understand what it means. For the Shoortans it's a signal that you're not supposed to go beyond the wall and you're supposed to remain within where life is stable. So this idea, as you said, plays an ideological role in the sense that for the dominant faction it becomes a reason to ensure the continuance of status-quo but for the Young Tarafians it becomes a reason to break the status quo. Later on in the novel you have certain dispute about its exact meaning and where it's coming from that enables, not to give away spoilers, some people to find a way to break the status quo. BL: I want to pick you up what you say about there being some specific cultural references that make more sense to an Indian reader. For me, when I was reading the book, one of the really enjoyable things was the many references to classical Greece and Rome. You already mentioned Harrington as one of your sources, and I wanted how these different literary and historical sources influenced your writing? GB: I think that this a function of growing up in India in the 1990s, where there is this whole range of influences that you're exposed to as a child. One set of influences is you know a lot of the classical Greek and Roman stuff in translation. You would have noticed that there is a progressive councillor, a social reformer who wants to democratise land ownership within the city and he's obviously based on Gracchus, the Roman tribune. But in my book his name is Sanchika and Sanchika was actually the pen name of E. M. S. Namboodiripad, the first Indian communist elected Chief Minister who also carried out land reform. There are also other myths in the book that are a blend of various influences. In an early part of the book there is this myth about two birds who try and fly up to the sun and one of them is about to have their wings burnt off but the other one protects them by shielding them. Now, this might sound like the Icarus myth, but it's actually a story from the Ramayana involving Jatayu and his elder brother, which shows you that there's a common source to all these myths and they evolve a little differently in different countries. But what may look like an Icarus myth to a western reader is actually slightly different, it has its own source in Indian myth. One specific reference that I want to point out, which speaks to the question of ideology and some of the underlying debates in the book. At one point in the book, one of the scientists, says that look, you can vote for or against decisions, you can have your referendum, but you can’t really vote against the wall. Because the wall is part of reality, it's always there. That's directly a reference to Jean-Claude Juncker saying in 2015 after the Greek election that ‘there can be no democratic choice against the European treaties’. What that’s basically saying is look, you can have your domestic votes, in your own little country, but you can’t vote against neoliberalism, against the governing philosophy of the EU. So, one of themes I'm exploring in The Wall is that neoliberalism, and capitalism in general, has this whole myth of scarcity. A lot of the edifice of neoliberalism depends upon this ideology of scarcity and there not being enough. But what if you had a situation in which that scarcity was not an ideological construct but was literally a key part baked into the world and there was an identifiable reason why there was scarcity. Then how would society evolve and what would the arguments be. BL: The global melding of myths is really one of the many strengths of the book. Another that really impressed me is how you managed to weave in discussions about the Sumer’s constitutional history and political structure and do so in a way that is plausible and never gets in the way of the narrative. There’s not that much sci-fi that really takes the politics of the world-building quite so seriously (China Mieville perhaps comes to mind). I suppose this bring us to the somewhat inevitable question about how your day-job, your academic work, relates to you science fiction writing. In some interviews you’ve been a little hesitant to draw those links. But when I was listening to your ideas on the transformative constitution in the first half of our interview, it did seem that there were some similarities in The Wall. Especially the idea that constitutionalism goes beyond the political and that it matters to social questions and the social sphere. So I guess I want to ask a quite open question, to what extent, if at all, there are these links between legal and constitutional work and your fictional writings? GB: I think that, first of all, it's just the fact that most science fiction writers have a day job. Apart from the lucky few who can make a living off their writing, they most have day jobs and that always bleeds into bleeds into the science fiction. A physicist, or an engineer, when they write science fiction they ensure that the spaceship has the right dimensions and can fly, and so similarly, when a lawyer writes science fiction, they will ensure that the underlying legal arrangements are persuasive and reflect the larger world. So in that sense, your professional specialisation will always bleed into your writing because you’re just aware of the role that plays in whatever you're writing. I think that, for me, the understanding that has come from many years of being in legal practice and also writing about law is how law and legal structures constitute the internal plumbing of the world and they're always there. We’re not always are aware of them, but they exist and they are what make actions certain actions possible or not possible. That’s the kind of thing that once you see you can't really unsee. So when you're doing world building for science fiction, you will factor in the law and constitutional arrangements into that world building. And where societies are under heightened stress, whether Brexit in the UK or what Trump did in the US or the Citizenship Amendment Act in India, people do talk about the constitution at that point of time. Because that's when it really comes to the fore, so it's quite natural for people living in societies that are undergoing a certain kind of stress to think about, reflect about and debate constitutional arrangements. And that is something that is reflected in the book, because it is a society under stress and it is destabilised by the Young Tarafians who want to get beyond the wall. They are claiming that they have good reasons to do so and people want to stop them. So obviously the issue of what is allowed, what isn't allowed, what the law allows, what the society’s political arrangements allow, would come to the fore and would be discussed. So in that sense, of course, being a lawyer influences the vocabulary, in which those claims might be framed. To that extent there is an overlap and influence. I think what I'm hesitant about, what I've been a little uncomfortable about, is people saying that this is legal science fiction or legal speculative fiction, that it is centered on law. Because, first of all, I'm telling a story, and that's what matters. As a writer you are trying to tell a good story and then you have all the things that go into making it a plausible world. Whether that is, for example, the understanding that in a semi-closed system, with no fauna, all your plants would need to be self-pollinating. So the only plants that your city can have are self-pollinating plants, so you then have to ask is cotton self-pollinating? It turns out it is, and therefore the clothes will be made of cotton. So just like you pay attention to that kind of thing to make your world building plausible, you also pay attention to law to make it plausible. The fact that the writer is a lawyer should not distract attention from the story. BL: We’re getting to the end of our time, so I wanted to ask how writing on the sequel is going. I think its called The Horizon? GB: Yes, part two is called the Horizon and was finished in January. It's supposed to come out in September but given the Indian covid situation I don't know if that will happen or if it will be delayed. I haven't yet followed up because things are bad right now, and I think nobody should be pushed right now to work in India. So the formal release date was September and I don't know if it will be September, maybe a couple of months after. BL: Of course. When it does appear I’m certainly going to buy it as soon as it's available. GB: Thank you! Thank you so much, I'm so glad you enjoyed the book. by Jonathan Joseph

Jacques Derrida died some 16 years ago and might seem an unlikely candidate for providing an analysis of the current Covid-19 epidemic. Yet I will summon Derrida here to provide a certain view of these exceptional times, drawing mainly on the arguments of his book Specters of Marx. Here, he remarkably refers to his philosophy of deconstruction—an approach more focused on text and meaning than on the material world—as a radicalisation of a certain spirit of Marxism.[1] Using Marx to question the smug triumphalism of capitalism’s liberal supporters, this intervention seemed as much a challenge to the postmodern indulgencies of his own followers.