|

13/9/2021 'We are going to have to imagine our way out of this!': Utopian thinking and acting in the climate emergencyRead Now by Mathias Thaler

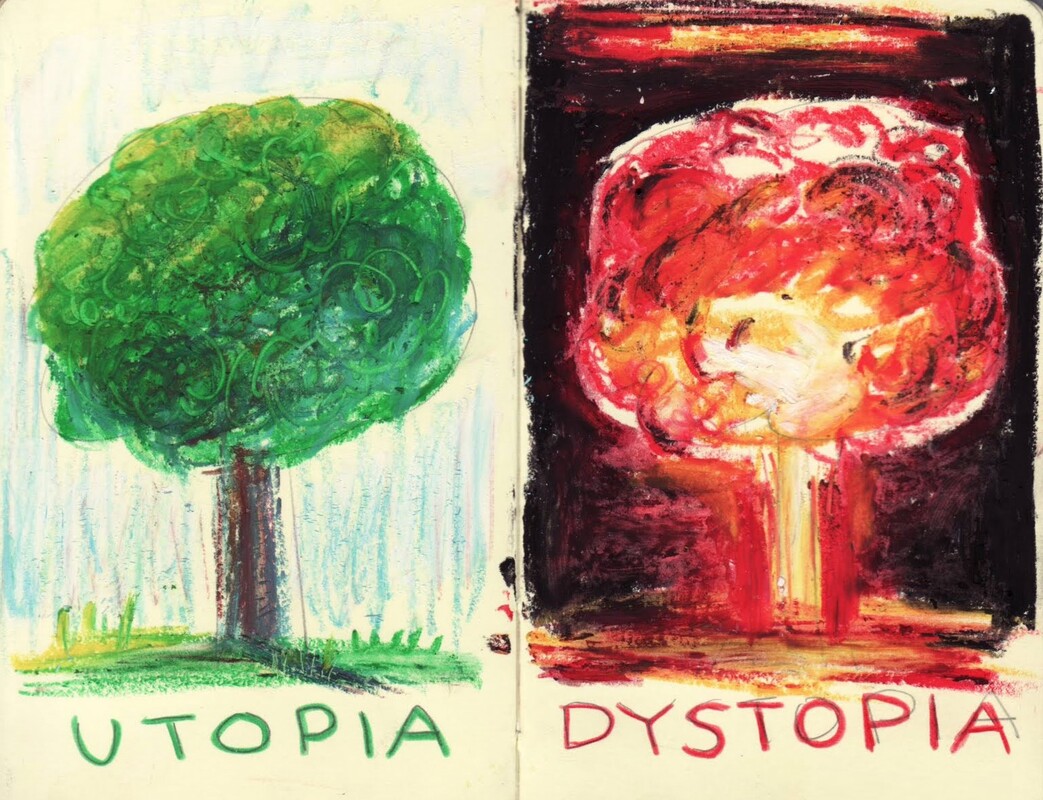

In the public debate, the climate emergency has broadly given rise to two opposing reactions: either resignation, grief, and depression in the face of the Anthropocene’s most devastating impacts[1]; or a self-assured, hubristic faith in the miraculous capacity of science and technology to save our species from itself.[2]

But, as Donna Haraway forcefully asserts, neither of these reactions, relatable as they are, will get us very far.[3] What is called for instead is a sober reckoning with the existential obstacles lying ahead; a reckoning that still leaves space for the “educated hope”[4] that our planetary future is not yet foreordained. To accomplish these twin goals, utopian thinking and acting are paramount.[5] What could be the place of utopias in dealing with the climate emergency? To answer this question, we first have to clear up a widespread misunderstanding about the basic purpose of utopianism. Many will suspect that the utopian imagination appears, in fact, uniquely unsuited for illuminating the perplexing realities of a climate-changed world. On this view, utopianism amounts to the kind of escapism we urgently need to eschew, if we are serious about facing up to the momentous challenges the present has in store for us. Indulging in blue-sky thinking when the planet is literally on fire might be seen as the ultimate sign of our species’ pathological predilection for self-delusion. The charge that utopias construct alluring alternatives in great detail, without, however, explaining how we might get there, possesses an impressive pedigree in the history of ideas. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels excoriated the so-called utopian socialists for being supremely naïve when they paid scant attention to the role that the revolutionary subject—the proletariat—would have to play in forcing the transition to communism.[6] It is important to remark that the authors of the Communist Manifesto did not take issue with the glorious ideal that the utopian socialists venerated, quite to the contrary. Their concern was rather that focusing on the wished-for end point in history alone would be deleterious from the point of view of a truly radical politics, for we should not merely conjure what social form might replace the current order, but outline the concrete steps that need to be taken to transform the untenable status quo of capitalism. Marx and Engels were, to some degree, right. There are many types of utopian vision that serve nothing but consolation, trying to render an agonising situation more bearable by magically transporting the readers into a wonderous, bright future. These utopias typically present us with perfect and static images of what is to come. As such, they leave not only the pivotal issue of transition untouched, they also restrict the freedom of those summoned to imaginatively dwell in this brave new world—an objection levelled against utopianism by liberals of various stripes, from Karl Popper to Raymond Aron and Judith Shklar.[7] Yet, not all utopias fail to reflect on what ought to be practically done to overcome the existential obstacles of the current moment. Non-perfectionist utopias are apprehensive about both the promise and the peril of social dreaming.[8] In the words of the late French philosopher Miguel Abensour, their goal consists in educating our desire for other ways of being and living.[9] This wide framing allows for the observation of a great variety of utopias within and across three dimensions of thinking and acting: theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, as paradigmatically enacted in intentional communities.[10] The interpretive shortcut that critics of utopianism take is that they conceive of this education purely in terms of conjuring perfect and static images of other worlds. However, utopianism’s pedagogical interventions can follow different routes as well.[11] From the 1970s onwards, science fiction writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Marge Piercy and Octavia Butler started to build into their visions of the future modes of critically interrogating the collective wish to become otherwise.[12] Doubt and conflict are ubiquitous in their complex narratives. Social dreaming of this type turns out to be the opposite of escapism: as a self-reflective endeavour, it remains part and parcel of any radical politics worth its salt.[13] The education of our desire for alternative ways of being and living amounts to an intrinsically uncertain enterprise, always at risk of going awry, of collapsing into totalitarian oppression. There is, hence, no getting away from the fact that utopias can have problematic effects. But this does not mean we should jettison them altogether. The risks of not engaging in social dreaming far outweigh its obvious benefits: any attempt to cling to business as usual, at this moment of utmost emergency, will surely trigger an ever more catastrophic breakdown of the planetary condition, as the latest IPCC draft report into various climate scenarios unambiguously establishes. The path forward, then, entails acknowledging the eminent dangers in all efforts to conjure alternatives; dangers that can be negotiated and accommodated via theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, but never fully eliminated. This insight is aptly expressed in Kim Stanley Robinson’s work: "Must redefine utopia. It isn’t the perfect end-product of our wishes, define it so and it deserves the scorn of those who sneer when they hear the word. No. Utopia is the process of making a better world, the name for one path history can take, a dynamic, tumultuous, agonising process, with no end. Struggle forever."[14] If we recast utopianism along Robinson’s lines, what might be its lessons for navigating our climate-changed world? To answer this question, I propose we distinguish between three mechanisms that utopias deploy: estranging, galvanising, and cautioning. All utopias aim to exercise their critique of the status quo by doing one or several of these things. This can be illustrated through a quick glance at recent instances of theory-building and storytelling that grapple directly with our climate-changed world. Let us commence with estranging. When utopias make the extraordinary look ordinary, they seek to unsettle the audience’s common sense and therefore open up possibilities for transformation. One way of interpreting Bruno Latour’s recent appropriation of the Gaia figure is, accordingly, to decipher it as a utopian vision that hopes to disabuse its readers of anthropocentric views of the planet.[15] While James Lovelock initially came up with the idea to envisage Earth in terms of a self-regulating system, baptising the entirety of feedback loops of which the planet is composed with the mythological name “Gaia”, Latour attempts to vindicate a political ecology that repudiates the binary opposition of nature and culture, which obstructs a responsible engagement with environmental issues. From this, a deliberately strange image of Earth emerges, wherein agency is radically dispersed across multiple forms of being.[16] In N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, to refer to an interesting case of politically generative fantasy, our home planet is depicted as a vindictive agent that wages permanent war on its human occupants.[17] The upshot of this portrayal of the planetary habitat as a living, raging being, rather than a passive, calm background to humanity’s sovereign actions, is that the readers’ expectations of their natural surroundings are held in abeyance. Jemisin’s work captures Earth and its inhabitants through powerful allegories of universal connectedness—neatly termed “planetary weirding”[18]. What is more, the Broken Earth trilogy also sheds light on the shifting intersections of class, gender, racial, and environmental harms.[19] Hence, narratives such as this unfold plotlines that produce estrangement: they come up with imagined scenarios, which defamiliarise us from what we habitually take for granted.[20] Galvanising stories casts utopian visions in a slightly different light. These narratives describe alternatives whose purpose resides in revealing optimistic perspectives about the future. In contemporary environmentalist discourse, ecomodernists enlist this kind of emplotment strategy, most notably through their provocative belief that science and technology might eventually expedite a “decoupling” of human needs from natural resource systems.[21] Kim Stanley Robinson’s Science in the Capital trilogy inspects this alluring proposition with inimitable insight.[22] In his account of how the American scientific community might marshal its expertise to redirect the entire Washington apparatus onto a sustainable policy platform, Robinson attempts to establish that viable paths out of the current impasse do already exist—if only all the actors involved finally recognised the severity of the situation. The chief ambition behind this utopian frame is thus to affectively galvanise an audience that is at the moment either apathetic about its capacity to transform the status quo or paralyzed by the many hurdles that lie ahead. Finally, cautionary tales follow a plotline that is predicated on a bleaker judgment: unless we change our settled ways of being and living, the apocalypse will not be averted. Dystopian stories pursue this instruction by excavating hazardous trends that remain concealed within the current moment. Commentators such as Roy Scranton[23] or David Wallace-Wells[24] maintain that there is little we can do to slow down the planetary breakdown and the eventual demise of our own species. Margaret Atwood’s dystopian MaddAddam trilogy takes one step further when she prompts the reader to imagine how life after the cataclysmic collapse of human civilisation might look like.[25] The main task of this sort of narrative is to warn an audience about risks that are already present right now, but whose scale has not yet been fully appreciated in the wider public.[26] These three compressed cases show that the utopian imagination has much to add to the public debate around climate change; a debate that is about so much more than just plausible theories or appealing stories. Conjuring alternatives is as much about the modelling of other ways of being and living as it is about spurring resistant action. Social dreaming does not only involve abstract thought experiments; it also prompts a restructuring of human behaviour and as such proves to be deeply practical.[27] The climate emergency has, among many terrible outcomes, triggered a profound crisis of the imagination and action.[28] In this context, and despite legitimate worries about the deleterious aspects of social dreaming, we cannot afford to discard the estranging, galvanising, and cautioning impact that utopias generate. As one of the protagonists of the Science in the Capital trilogy declares: “We’re going to have to imagine our way out of this one.”[29] Acknowledgments With many thanks to Richard Elliott for the invitation to write this piece as well as for useful comments; and to Mihaela Mihai for productive feedback on an earlier draft. The research for this text has benefitted from a Research Fellowship by the Leverhulme Trust (RF-2020-445) and draws on work from my forthcoming book No Other Planet: Utopian Visions for a Climate-Changed World (Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022). [1] For a useful compendium of resources on the rise of (negative) emotions during the current climate crisis, see: https://www.bbc.com/future/columns/climate-emotions [2] The best example of this attitude can probably be found in Bill Gates’ recent endorsement of such solutionism. See: How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021). [3] Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). [4] Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope: Volume 1, trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight, Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 7, 9. [5] For a groundbreaking study, see: Lisa Garforth, Green Utopias: Environmental Hope before and after Nature (Cambridge: Polity, 2018). [6] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The Communist Manifesto,” in Selected Writings, by Karl Marx, ed. David McLellan, 2nd ed. (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 245–71. [7] On the anti-utopianism of these so-called “Cold War liberals”, see: Richard Shorten, Modernism and Totalitarianism: Rethinking the Intellectual Sources of Nazism and Stalinism, 1945 to the Present (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 109–49. [8] Lucy Sargisson, Fool’s Gold? Utopianism in the Twenty-First Century (Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). [9] Miguel Abensour, “William Morris: The Politics of Romance,” in Revolutionary Romanticism: A Drunken Boat Anthology, ed. Max Blechman (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1999), 126–61. [10] Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” Utopian Studies 5, no. 1 (1994): 1–37. [11] Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia, Student Edition (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2011); Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstruction of Society (Houndmills/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [12] On Le Guin and especially her masterpiece The Dispossessed, see: Tony Burns, Political Theory, Science Fiction, and Utopian Literature: Ursula K. Le Guin and the Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008); Laurence Davis and Peter Stillman, eds., The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2005). [13] Tom Moylan, Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination, ed. Raffaella Baccolini, Classics Edition (1986; repr., Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014). [14] Kim Stanley Robinson, Pacific Edge, Three Californias Triptych 3 (New York: Orb, 1995), para. 8.10. [15] Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, E-book (Cambridge/Medford: Polity, 2017). [16] See also: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010). [17] The Fifth Season, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 1 (New York: Orbit, 2015); The Obelisk Gate, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 2 (New York: Orbit, 2016); The Stone Sky, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 3 (New York: Orbit, 2017). [18] Moritz Ingwersen, “Geological Insurrections: Politics of Planetary Weirding from China Miéville to N. K. Jemisin,” in Spaces and Fictions of the Weird and the Fantastic: Ecologies, Geographies, Oddities, ed. Julius Greve and Florian Zappe, Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 73–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28116-8_6. [19] Alastair Iles, “Repairing the Broken Earth: N. K. Jemisin on Race and Environment in Transitions,” Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 7, no. 1 (July 11, 2019): 26, https://doi.org/10/ghf4k5; Fenne Bastiaansen, “The Entanglement of Climate Change, Capitalism and Oppression in The Broken Earth Trilogy by N. K. Jemisin” (MA Thesis, Utrecht, Utrecht University, 2020), https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/399139. [20] Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: Studies in the Poetics and History of Cognitive Estrangement in Fiction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978). [21] John Asafu-Adjaye, et al., “An Ecomodernist Manifesto,” 2015, http://www.ecomodernism.org/; See also: Manuel Arias-Maldonado, “Blooming Landscapes? The Paradox of Utopian Thinking in the Anthropocene,” Environmental Politics 29, no. 6 (2020): 1024–41, https://doi.org/10/ggk4vj; Jonathan Symons, Ecomodernism: Technology, Politics and the Climate Crisis (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019). [22] Forty Signs of Rain, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 1 (New York: Bantham, 2004); Fifty Degrees Below, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 2 (New York: Bantham, 2005); Sixty Days and Counting, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 3 (New York: Bantham, 2007). [23] Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization, E-book (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015). [24] The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming, E-book (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019). [25] Oryx and Crake, E-book, vol. 1: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2003); The Year of the Flood, E-book, vol. 2: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2009); MaddAddam, E-book, vol. 3: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2013). [26] Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History: A Study of Modern Despotism, Its Antecedents, and Its Literary Diffractions, First edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). [27] In the 1970s, the Swiss sociologist Alfred Willener coined the term “imaginaction” to capture what is distinct about action facilitated through imagination and imagination stirred by action. See: Alfred Willener, The Action-Image of Society: On Cultural Politicization (London: Tavistock Publications, 1970). [28] Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, E-book (London: Penguin, 2016), para. 9.2. [29] Robinson, Sixty Days and Counting, para. 58.11. 14/6/2021 Ideology, Transformative Constitutionalism, and Science-Fiction: An Interview with Gautam BhatiaRead Now by Udit Bhatia and Bruno Leipold

Udit Bhatia: It might be useful for our readers if you could start off by saying what the idea of transformative constitution is and what work it does in your reading of the Indian constitution.

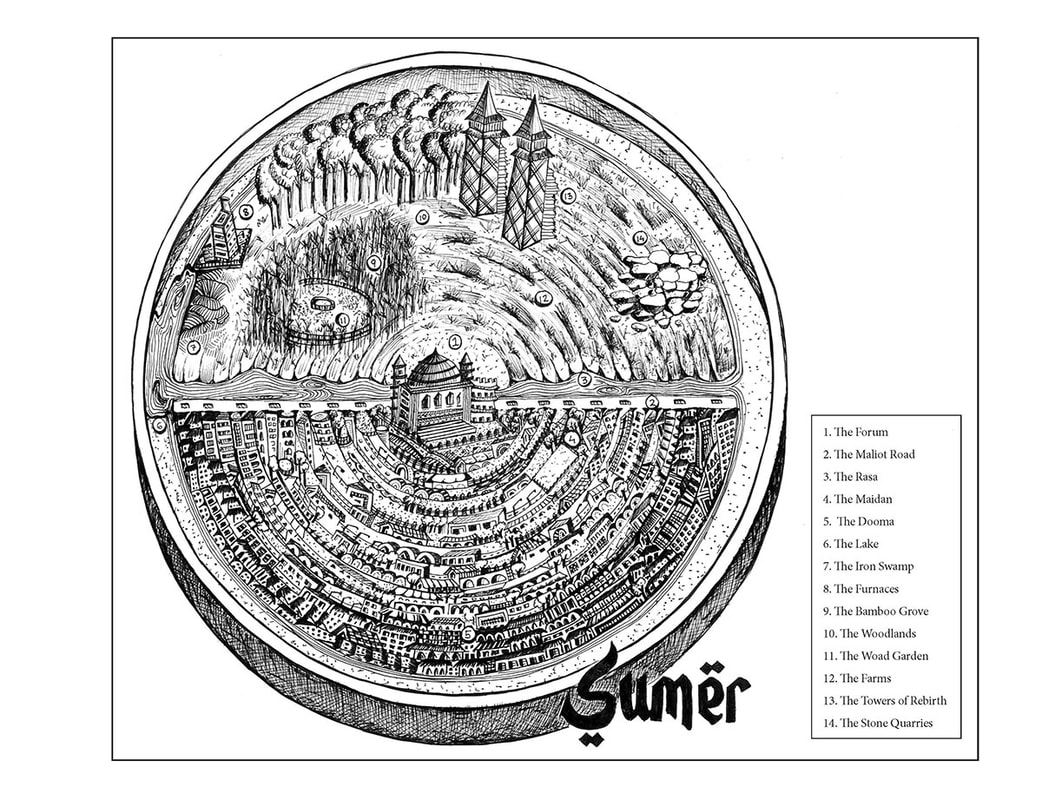

Gautam Bhatia: The term transformative constitutionalism or transformative constitution originated in post-apartheid South Africa and it had a, it is a contested term. My understanding of it is that there are basically two things about it. First, that it's distinctively post-liberal in its approach to constitutionalism. There was a certain classic understanding of constitutions as being about limiting state power. That is an understanding that comes from the American Constitution that has had a disproportionate influence on constitutionalism across time and across the world. Transformative constitutionalism is post-liberal in the sense that it understands the role of a Constitution to be more than containing the state and it actually involves directing the state towards achieving certain social goals. Another really fundamental tenet of liberal ideology is the idea of neutrality. For example, John Rawls’s ‘right over the good’, where we can disagree over goals but there are certain rights- based principles that are non-negotiable. But transformative constitutionalism specifically says that there’s a certain vision of society we're trying to get towards. In that sense, it’s also post-liberal that you could call it perfectionist again to use the term from analytical philosophy. But it has a certain blueprint of the society that it envisages as being the good society and it sees constitutions and constitutionalism as vehicles for getting there. And then it also calls for changing legal culture, so it's not just what a constitution can do. To make the constitution do that you have to then alter the way people argue in court, the things that courts can do and just the structure of legal argument and legal culture. So the original article by Karl Klare, a labour lawyer talked about both these things, and often a bit about legal culture is forgotten and in my book, the term transformative constitutionalism broadly does something similar in the sense that it specifically talks about the Indian Constitution as being post-liberal in the sense that it was understood to be an intervention, both with respect to containing state power and providing political and civil rights and transforming subjects into citizens. But also, it was meant to bring about a far-reaching transformation in Indian society and, specifically, tackling private power. So power that exercise through institutions, whether they are social institutions like caste or economic institutions like the marketplace or cultural institutions, various religions. The Constitution, constitutional law, ideas of rights were envisioned as applying to what we classically understand as the private domain. In that sense the Indian constitution was meant to challenge the ideology, so to say, of the public-private divide. That's how I understand the transformative constitution in the Indian context. UB: Perfect, thanks Gautam! I think one of the things that struck me was how much of the work of excavating these transformative elements happens through your reading of dissenting judgments. Now someone might look at that and think ‘well, great, there’re all these resources you’ve managed to identify in India’s legal history’. But on the other hand, one might think ‘why is this all just dissent—that’s worrying!’. So could you say a bit more about what's going on here? GB: Historically the constitution's transformative impulses have been submerged by the adjudicatory body that is charged with being the final word on the Constitution, which is the Supreme Court of India. The dominant interpretation that the Indian Supreme Court has placed upon the Constitution and its provisions has been a conservative one. The transformative interpretation exists, and I use Edward Said’s idea of the ‘contrapuntal canon’. So there is a canon—there is the Indian constitutional canon of judgments which, despite a contrary long-standing public perception, encouraged by the Court, and by various scholars, is conservative. But then there are these dissenting judgments, some High Court documents, and the odd majority judgements as well. If you read these against the grain, in a contrapuntal way, you can excavate the transformative impulses that are there in the Constitution’s text and structure. UB: As one reads the book, you get an idea of the substantive transformative elements in the constitution—especially their engagement with private regimes of power, or their focus on community ties that can infringe individual autonomy in all sorts of ways. But the other side of this story might be the conservatism of the constitutional text in procedural terms: the fact that the constitution set up elitist representative institutions with few opportunities for contestation by ordinary citizens. So, in a way, the transformative constitution was always likely to end up as a dissenting note. I wonder how wedded you are to the idea of transformative constitutionalism through the constitutional text. GB: The great thing about texts is that they’re always open to interpretation. Something like a constitutional text, given the complicated social histories leading up to the framing of the Constitution, given that constitutional texts are invariably in the language of the abstract principle and not concrete commitments, given that a constitutional text is always open to a diverse range of interpretation—all this makes the interpreters task to bring together different elements, text, history, structure and so on—and fashion the most persuasive reading possible of the constitutional document and I think it is eminently possible to fashion a conservative reading of the document, given its history, and given the text. And that project hasn't happened yet, in my view, although some of H.M. Seervai’s work gestures towards that—though I wouldn't call it necessarily a right-wing interpretation. It is conservative in just placing the boundaries of interpretation as being contained by the text and not beyond that. So it is an essentially a legally conservative reading that he provides, although ironically It is far more rights-protective than a lot of the supreme court's own judgments. But the task that I see for myself as the interpreter is to use these materials that are in existence to fashion a persuasive transformative reading of the text of the constitutional law. I don't think there is a view from nowhere, and there can’t be a non-engaged engaged standpoint. And my standpoint is from the internal perspective, which is that of a lawyer who works with the Constitution and who believes that there’s a set of important progressive goals that a Constitution is a vehicle towards achieving. It‘s a perspective which says that the Indian Constitution can and should be persuasively interpreted, so that it leads us towards those goals. I don't claim for myself the standpoint of an objective interpreter. I don't think there is any such standpoint but I am a participant and I'm saying ‘look, this is my argument and see if it's a good argument’. If somebody else has a better conservative argument for the Constitution, then fair enough. If that persuades you, as the public, then that’s perfectly fine. This is my argument I am placing before you and I hope that it persuades you. UB: You’ve made it quite clear in the book that you’re telling us only the judicial side of the story of transformative constitutionalism in India, and that’s not the whole story. But could you say more about the trajectory of this idea outside the courts? GB: I would recommend Rohit De’s book “A People's Constitution” that deals with the first decade after independence, throws light on how ordinary Indians understood the Constitution, leveraged it, and used it as a tool to expand their rights. And they weren't always successful but It really shows you how the Constitution became an idiom for language outside of the courts. In the last few years—and this is a really cliched example by now—but the CAA protests are a really good example of the constitutional idiom going beyond the courts. I think what was really interesting about the CAA protests was that the protesters were really clear about the fact that they were advancing an understanding of the Constitution that derived its legitimacy and validity, not in the hope that it would be one day accepted by the Supreme Court, but by the force of argument alone outside of the Court. They fashioned a certain reading of the preamble of the Constitution, a certain reading of Article 14, the equality clause, and they were very careful to decentre the Supreme Court. If you look at the history of those protests and how the Constitution was used, it was always a reliance upon the document and there was no reference to the fact that there were pending constitutional challenges in the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court might or might not vindicate this understanding. It was a reading of the construction that stood on its own legs. That is one of the I think standout examples of transformative constitutionalism that did not rely upon the court. If you look at a lot of work being done in Assam right now, in the aftermath of the NRC by lawyers like Aman Wadud, you find that they're setting up these Constitution centres in various places, explaining the Constitution. Again, they’re doing this without necessarily anchoring it to Supreme Court’s understandings of the constitution. UB: Over the last few years, commentators like yourself have noted the rise of authoritarianism in India—and the courts have not been immune from this. You’ve expressed concerns about the extent to which one can continue pretending the judiciary operates along the line of rule of law. According to you, what’s the role of the lawyer in such circumstances? GB: I think the role of the lawyer is a very difficult one, especially when it involves issues like the CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act), Kashmir, Aadhar—basically, issues involving state power and the constitution. You need a set of lawyers who will represent a client’s case as if everything was completely normal, as if this were a functioning democracy, with independent institutions. You need one set of lawyers, in my view, who will do that because that's work that needs doing. You also need a set of lawyers, whose knowledge of the practice of lawyering and judging, which is an internal perspective—because they've been in court—and no matter how careful an external analysis might be given, given the number of context-specific practices that can have developed over the years, there are things a lawyer sees just by virtue of being in court that are impossible to see from outside. So I think you also need a set of lawyers who draw upon that experience to mount a critique of the Court and the role the Court in checking or failing to check authoritarian tendencies and centralisation and so on. I think that you need both kinds because as long as courts exists as centres of power, you need people who will speak in the language of the institution. But if that is the only kind of speaker that there is, the perception will remain of a well-functioning institution. So you will also need to have people who will critique the functioning of the institution. Yet, if you only have people who do that then there'll be nobody left to make the case inside the court. You need a combination of both things, I think. It's every lawyer’s decision, a question of conscience, what role you want to occupy. You have to have one of the two roles, assuming you have the privilege, the resources, and the luxury of choosing. I think one of those two roles is important when the situation is one in which authoritarian tendencies are overwhelming institutions. Bruno Leipold: Oh, maybe I could jump in quickly and ask one question about the book. One thing that struck me is that you quite extensively draw on the idea of republican freedom. I would be quite interested to hear more the way in which debates about republican freedom were helpful to formulating your arguments about transformative constitutionalism? UB: It also seemed that this was also one of the shorter chapters, and the sense I was getting was this isn’t something that's come up much with the court—except in a judgment where exploitative economic conditions for workers is interpreted as something like forced labour. Could you give us a sense of the judiciary’s further engagement with this idea? Has this notion come up again in other cases? GB: Yeah so the second question is a shorter one so in brief, no, the PUDR judgement—which held that the right against forced labour includes a right to a minimum wage—is the only Supreme Court judgement to have given that interpretation to article 23. You find one High Court judgment 1994 in Allahabad that said something similar. But that's it, and I think it's just because the radical implications of that argument. So, after the PUDR judgement, there were a couple of Supreme Court judgements where people tried to rely upon PUDR as precedent and the court just shut them down and distinguished the case, and you know basically just kind of buried that that judgment. And I think it's obvious why because its just the implications are radical it, it would mean basically an anti-capitalist reading of the Constitution, which our courts or any set of courts anywhere are not willing to sanction. As far as the role of republicanism goes, I think that the insight that republicanism provides for that kind of a reading of the forced labour clause is the focus on freedom as non-domination. Now classical republican theorists still locate the source of domination in a personalised manner, so you still need an identifiable person to pin that dominating power on. Which, of course, is not feasible and that's where workplace republicanism comes in, that is expressed I think most powerfully in writings of scholars like Corey Robin and William Claire Roberts and so on, is a depersonalisation and institutional or structural view of domination and of power. So, if you just look at the classical understanding of fundamental rights and why they were applicable against the state, the idea was that the state has the has a monopoly over power. Right, and this idea of the monopoly then kind of runs through constitutionalism so when you want to affix liability for rights violations on a private party, a question that courts often ask is that does this private party exercise the monopoly over an important good or service, so if, for example, a body has monopoly over all the water supply, in an area or electricity in an area and it's discriminating and not say providing water to people of certain religion right, then the court can often argue that okay, because of its monopoly this private body has a state-like function, and therefore the constitutional rights provisions apply to it and therefore you know we are you know stopping this from going forward. What that ignores is that you don't need to have a monopoly, but it may still be impossible to exit from an institution—which is the classic you know the whole point about the workplace and about labour, the labour market is that no individual capitalist has a monopoly, in fact, you know the capitalist is as constrained by the demands of capitalism, as the worker, it is the capitalist that has to constantly ensure that you know they're cutting costs and increasing profits because otherwise they’ll get out of business, and that we know that going back to Marx. So it's not it's not an individual capitalist who is a monopolist but it is the kind of a structure or the institution of the labour market that’s exercising that power through individual capitalists. So workplace republicanism I think gives us a way or a method to frame that insight and constitutional language and to say that therefore workers have constitutional rights against their bosses, even though a boss, is not the state. UB: It's interesting you bring this up because there's so much in the book on private regimes of power, and that the book ends on the dangers of Adhaar (India’s biometric identity system). And it strikes me that one of the risks of Adhaar is very much it becoming something that private players start to emphasise; for instance, by linking private services to the Aadhar system. Is there a relationship of complicity between these private regimes of power and state power? GB: Yeah, so I think in the Aadhaar case private regimes are operating under delegated powers from the states because Aadhaar is ultimately a nationwide centralised biometric identification system where the centralisation is by the state; the UIDAI is a state body and to the extent that private players can use the database, they do it on sufferance under Section 57 which was struck down, but then, of course pretty shamelessly reenacted by the government. So in the Aadhaar case it's actually the state power that’s being parceled out to private parties now, of course, I mean there is an argument to be made that you know the State itself is a terrain of class conflict, and so, to what extent is actually distinct from private parties? So I think that’s a political theory argument, but in terms of at least Constitutionalism and the law, the Adhaar cases I think straightforwardly involves state power and private parties do have and continue to weaponise the database for you know data gathering, data collection and use of data and denial of service and so on, but that, but their authority still flows from a law whereas the argument on private regimes was more that if you have something like you know caste enforced you know, social boycotts, it’s not really relying on the state in at least formal terms. Of course, I mean there's a long argumentative tradition coming from the legal realists in the US, that ultimately the legal regime is gapless so you know I mean, even if there is no formal law, the state by its inaction is allowing things to happen so there's always the state involved and in that sense there's no real private action that is not either sanctioned by or the sufferance of the state. So you go down that route, then of course I mean the States always involved, you know in every private action or if you don't go down that route, then you know the distinction between state sanctioned law, as in the Adhaar case and the case of caste boycott, cases where private employers have not been paying a minimum wage, and so on. UB: Bruno I might let you take over now and may come back to them after you're done depending how much energy we leave him with. BL: So let’s turn to the literary side of things. I read The Wall in December and I want to start by saying what a fantastic achievement it is. There’s not many people in the world that can write both constitutional theory and beautiful, engaging science fiction! What I really loved about the book, and I think quite a few reviews of the book have picked up on this, is how impressive the level of world building is. You set out everything from the city’s origin myths, its constitutional history, its religions, its literary culture—it’s all there. Perhaps I could start by asking if you could give our readers a sense of what the book is about and also what led you to write it? Its, of course, quite a gear shift from your day job as a constitutional theorist! GB: Thank you! I’ll start with the second question. So while people might know me from my day job as a lawyer, I have actually been a science fiction fan since the age of 10 when my parents got me a copy of the Hobbit and then of Asimov's Foundation. Of course, the genre has moved beyond that now, but that was my introduction. So since the age of 10 I’ve been a huge fan and my teenage years were full of handwriting science fiction novels—pretty bad novels obviously! And then in 2015 I joined Strange Horizons the science fiction magazine as a non-fiction editor. I've been involved with them for the last five years now, five or six years. So my association with science fiction and fantasy, is something that is much older than my association with law and you know it's always been there and this novel actually began life back in 2008 when I was in college and I didn't at all know that I would go on to become you know, a full time lawyer and my day job or even stay with law, so its origins actually go back to even before I really got into law as a profession. As to what the book’s about to put it simply it's a speculative fiction somewhere at the borders of science fiction and fantasy. It is set in a city that is enclosed completely within a very high wall that nobody has crossed in living memory. There is abundant water (the source of which is unknown), but every other resource is scarce. But that scarcity is not an ideological imposition, it's actually physically scarce, and therefore, the food and the wood and the material required for clothes and so on are all actually limited quantities. And that influences the social, economic and cultural structures that are present in the city. It's not a dystopia because there is just about enough there for everyone to be able to live a life that is not a life of squalor or a life of want so it’s not a dystopic city, but it is stasis, and it is contained. And the core plot point is that there are a group of people who do want to find a way beyond the wall and know what lies beyond and the book is about their efforts to do that, in the face of hostility indifference and so on. BL: These are the Young Tarafians, right? Do you want to say something about the other ideological and political factions in the book and the underlying political structure? GB: At the broad level there are three factions in the city. One is the Governing Council of the city of Sumer, called the Council, or the Elders, which are a group of 300 people who govern the city. That political arrangement doesn't really borrow from any one thinker or historical example, but is most closely inspired by James Harrington the 17th century English philosopher, because of his idea of 300 people and how the balance between propertied and non-propertied classes is achieved. One interesting thing, for me at least, is that in Sumer they do democracy, but in a slightly different way, in that they are not elected, they are self-appointed, but every decision that they take is put to a referendum in the city. So although it's not democracy at the starting point as there are no elections, but it is a democracy at the at the end point, in that their decisions have to be put to a popular vote. However, there is one catch, which is that if you want to actually alter the property relations or underlying constitutional arrangements you have to have a two thirds majority. That’s an idea taken from Pinochet’s military constitution that enshrined neoliberalism, and that also gives you a clue about some of the underlying ideological debates in the book. So the Elders or the Council are the secular governing body of the city, and then there are the Shoortans—the religious group. That's drawn from the idea that if you have a city within a wall and its very clear that the wall is not natural, it was built by someone. And that someone gave to the citizens, the exact amount of resources in exactly the right balance to enable them to survive. So, clearly there is a governing intelligence or a governing hand behind this, which would lead to all kinds of duelling origin stories that are born from the realisation that there had to be a creator. So Shoortans have a set of beliefs about the creation and that the purpose of the wall is to keep them safe and therefore it should not be crossed. The final faction are the scientists, who are also called the Select, whose job it is to ensure that the city continues to run and to survive. They ensure that the proportions of the resources remain just right and that consumption remains at a level at which everyone can continue to survive. Because if you're living in a semi-closed system then a small change can lead to widespread devastation. So the scientist’s role is to ensure that things are kept on track and they're kind of exist with the other factions in a somewhat unstable equilibrium with each other, where you know there is a division of power, but it's a little uneasy and unstable. BL: Between these factions there's also ideological disagreement over what one of the central concepts of Sumer really means, that is the concept of ‘Smara’. GB: The idea of Smara is a bit of a cheat on my part because an Indian reader would kind of guess it’s meaning because it does draw from an Indian word. I'm sure when Udit reads the book when he sees the word Smara, he would have a rough idea of where that thought line is going but a non-Indian reader might not immediately. Smara, broadly is this idea of yearning or the yearning for a world without the wall, although what exactly it means is contested. It's a feeling that everyone has experienced, in the sense that everyone at certain times has this feeling of being enclosed, of being trapped, this yearning to know what's beyond that. To be able to see a world in which there is a horizon, because they also don't have a word for the horizon, but to see a world where actually you know everything you see isn't cut off by the wall. For some, this is actually a reason to go beyond the wall, to find out what's beyond that, so that they can put an end to this constant yearning and to understand what it means. For the Shoortans it's a signal that you're not supposed to go beyond the wall and you're supposed to remain within where life is stable. So this idea, as you said, plays an ideological role in the sense that for the dominant faction it becomes a reason to ensure the continuance of status-quo but for the Young Tarafians it becomes a reason to break the status quo. Later on in the novel you have certain dispute about its exact meaning and where it's coming from that enables, not to give away spoilers, some people to find a way to break the status quo. BL: I want to pick you up what you say about there being some specific cultural references that make more sense to an Indian reader. For me, when I was reading the book, one of the really enjoyable things was the many references to classical Greece and Rome. You already mentioned Harrington as one of your sources, and I wanted how these different literary and historical sources influenced your writing? GB: I think that this a function of growing up in India in the 1990s, where there is this whole range of influences that you're exposed to as a child. One set of influences is you know a lot of the classical Greek and Roman stuff in translation. You would have noticed that there is a progressive councillor, a social reformer who wants to democratise land ownership within the city and he's obviously based on Gracchus, the Roman tribune. But in my book his name is Sanchika and Sanchika was actually the pen name of E. M. S. Namboodiripad, the first Indian communist elected Chief Minister who also carried out land reform. There are also other myths in the book that are a blend of various influences. In an early part of the book there is this myth about two birds who try and fly up to the sun and one of them is about to have their wings burnt off but the other one protects them by shielding them. Now, this might sound like the Icarus myth, but it's actually a story from the Ramayana involving Jatayu and his elder brother, which shows you that there's a common source to all these myths and they evolve a little differently in different countries. But what may look like an Icarus myth to a western reader is actually slightly different, it has its own source in Indian myth. One specific reference that I want to point out, which speaks to the question of ideology and some of the underlying debates in the book. At one point in the book, one of the scientists, says that look, you can vote for or against decisions, you can have your referendum, but you can’t really vote against the wall. Because the wall is part of reality, it's always there. That's directly a reference to Jean-Claude Juncker saying in 2015 after the Greek election that ‘there can be no democratic choice against the European treaties’. What that’s basically saying is look, you can have your domestic votes, in your own little country, but you can’t vote against neoliberalism, against the governing philosophy of the EU. So, one of themes I'm exploring in The Wall is that neoliberalism, and capitalism in general, has this whole myth of scarcity. A lot of the edifice of neoliberalism depends upon this ideology of scarcity and there not being enough. But what if you had a situation in which that scarcity was not an ideological construct but was literally a key part baked into the world and there was an identifiable reason why there was scarcity. Then how would society evolve and what would the arguments be. BL: The global melding of myths is really one of the many strengths of the book. Another that really impressed me is how you managed to weave in discussions about the Sumer’s constitutional history and political structure and do so in a way that is plausible and never gets in the way of the narrative. There’s not that much sci-fi that really takes the politics of the world-building quite so seriously (China Mieville perhaps comes to mind). I suppose this bring us to the somewhat inevitable question about how your day-job, your academic work, relates to you science fiction writing. In some interviews you’ve been a little hesitant to draw those links. But when I was listening to your ideas on the transformative constitution in the first half of our interview, it did seem that there were some similarities in The Wall. Especially the idea that constitutionalism goes beyond the political and that it matters to social questions and the social sphere. So I guess I want to ask a quite open question, to what extent, if at all, there are these links between legal and constitutional work and your fictional writings? GB: I think that, first of all, it's just the fact that most science fiction writers have a day job. Apart from the lucky few who can make a living off their writing, they most have day jobs and that always bleeds into bleeds into the science fiction. A physicist, or an engineer, when they write science fiction they ensure that the spaceship has the right dimensions and can fly, and so similarly, when a lawyer writes science fiction, they will ensure that the underlying legal arrangements are persuasive and reflect the larger world. So in that sense, your professional specialisation will always bleed into your writing because you’re just aware of the role that plays in whatever you're writing. I think that, for me, the understanding that has come from many years of being in legal practice and also writing about law is how law and legal structures constitute the internal plumbing of the world and they're always there. We’re not always are aware of them, but they exist and they are what make actions certain actions possible or not possible. That’s the kind of thing that once you see you can't really unsee. So when you're doing world building for science fiction, you will factor in the law and constitutional arrangements into that world building. And where societies are under heightened stress, whether Brexit in the UK or what Trump did in the US or the Citizenship Amendment Act in India, people do talk about the constitution at that point of time. Because that's when it really comes to the fore, so it's quite natural for people living in societies that are undergoing a certain kind of stress to think about, reflect about and debate constitutional arrangements. And that is something that is reflected in the book, because it is a society under stress and it is destabilised by the Young Tarafians who want to get beyond the wall. They are claiming that they have good reasons to do so and people want to stop them. So obviously the issue of what is allowed, what isn't allowed, what the law allows, what the society’s political arrangements allow, would come to the fore and would be discussed. So in that sense, of course, being a lawyer influences the vocabulary, in which those claims might be framed. To that extent there is an overlap and influence. I think what I'm hesitant about, what I've been a little uncomfortable about, is people saying that this is legal science fiction or legal speculative fiction, that it is centered on law. Because, first of all, I'm telling a story, and that's what matters. As a writer you are trying to tell a good story and then you have all the things that go into making it a plausible world. Whether that is, for example, the understanding that in a semi-closed system, with no fauna, all your plants would need to be self-pollinating. So the only plants that your city can have are self-pollinating plants, so you then have to ask is cotton self-pollinating? It turns out it is, and therefore the clothes will be made of cotton. So just like you pay attention to that kind of thing to make your world building plausible, you also pay attention to law to make it plausible. The fact that the writer is a lawyer should not distract attention from the story. BL: We’re getting to the end of our time, so I wanted to ask how writing on the sequel is going. I think its called The Horizon? GB: Yes, part two is called the Horizon and was finished in January. It's supposed to come out in September but given the Indian covid situation I don't know if that will happen or if it will be delayed. I haven't yet followed up because things are bad right now, and I think nobody should be pushed right now to work in India. So the formal release date was September and I don't know if it will be September, maybe a couple of months after. BL: Of course. When it does appear I’m certainly going to buy it as soon as it's available. GB: Thank you! Thank you so much, I'm so glad you enjoyed the book. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed