|

29/4/2021 Alternative logics of ethnonationalism: Politics and anti-politics in Hindutva ideologyRead Now by Anuradha Sajjanhar

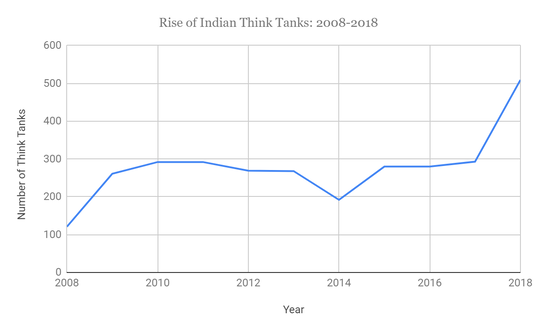

As in most liberal democracies, India’s national political parties work to gain the support of constituencies with competing and often contradictory perspectives on expertise, science, religion, democratic processes, and the value of politics itself. Political leaders, then, have to address and/or embody a web of competing antipathies and anxieties. While attacking left and liberal academics, universities, and the press, the current, Hindu-nationalist Indian government is building new institutions to provide authority to its particular historically-grounded, nationalist discourse. The ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, and its grassroots paramilitary organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), have a long history of sustained Hindu nationalist ideology. Certain scholars see the BJP moving further to the centre through its embrace of globalisation and development. Others argue that such a mainstream economic stance has only served to make the party’s ethno-centric nationalism more palatable. By oscillating between moderation and polarisation, the BJP’s ethno-nationalist views have become more normalised. They have effectively moved the centre of political gravity further to the right. Periods of moderation have allowed for democratic coalition building and wider resonance. At the same time, periods of polarisation have led to further anti-Muslim, Hindu majoritarian radicalisation. This two-pronged dynamic is also present in the Hindu Right’s cultivation of intellectuals, which is what my research is about. Over the last five to ten years, the BJP has been discrediting, attacking, and replacing left-liberal intellectuals. In response, alternative “right-wing” intellectuals have built a cultural infrastructure to legitimate their Hindutva ideology. At the same time, technical experts associated with the government and its politics project the image of apolitical moderation and economic pragmatism. The wide-ranging roles of intellectuals in social and political transformation beg fundamental questions: Who counts as an intellectual and why? How do particular forms of expertise gain prominence and persist through politico-economic conjunctures? How is intellectual legitimacy redefined in new political hegemonies? I examine the creation of an intellectual policy network, interrogating the key role of think tanks as generative proselytisers. Indian think tanks are still in their early stages, but have proliferated over the last decade. While some are explicit about their political and ideological leanings, others claim neutrality, yet pursue their agenda through coded language and resonant historical nationalist narratives. Their key is to effect a change in thinking by normalising it. Six years before winning the election in 2014, India’s Hindu-nationalist party, the BJP, put together its own network of policy experts from networks closely affiliated to the party. In a national newspaper, the former vice-president of the BJP described this as an intentional shift: from “being action-oriented to solidifying its ideological underpinnings in a policy framework”.[1] When the BJP came to power in 2014, people based in these think tanks filled key positions in the central government. The BJP has since been circulating dominant ideas of Hindu supremacy through regional parties, grassroots political organisations, and civil society organisations. The BJP’s ideas do not necessarily emerge from think tank intellectuals (as opposed to local leaders/groups), but the think tanks have the authority to articulate and legitimate Hindu nationalism within a seemingly technocratic policy framework. As primarily elite organisations in a vast and diversely impoverished country, a study of Indian think tanks begs several questions about the nature of knowledge dissemination. Primarily, it leads us to ask whether knowledge produced in relatively narrow elite circles seeps through to a popular consciousness; and, indeed, if not, what purpose it serves in understanding ideological transformation. While think tanks have become an established part of policy making in the US and Europe, Indian think tanks are still in their early stages. The last decade, however, has seen a wider professionalisation of the policy research space. In this vein, think tanks have been mushrooming over the last decade, making India the country with the second largest number of think tanks in the world (second only to the US). As evident from the graph below, while there were approximately 100 think tanks in 2008, they rose to more than 500 in 2018. The number of think tanks briefly dropped in 2014—soon after Modi was elected, the BJP government cracked down on civil society organisations with foreign funding—but has risen dramatically between 2016 and 2018. Fig. 1: Data on the rise of Indian think tanks from Think Tank Initiative (University of Pennsylvania) There are broadly three types of think tanks that are considered to have a seat at the decision-making table: 1) government-funded/affiliated to Ministries; 2) privately-funded; 3) think tanks attached to political parties (these may not identify themselves as think tanks but serve the purpose of external research-based advisors).[2] I do not claim a causal relationship between elite think tanks and popular consciousness, nor try to assert the primacy of top-down channels of political mobilisation above others. Many scholars have shown that the BJP–RSS network, for example, functions both from bottom-up forms of mobilisation and relies on grassroots intellectuals, as well as more recent technological forms of top-down party organisation (particularly through social media and the NaMo app, an app that allows the BJP’s top leadership to directly communicate with its workers and supporters). While the RSS and the BJP instil a more hierarchical and disciplinary party structure than the Congress party, the RSS has a strong grassroots base that also works independent of the BJP’s political elite.

It is important to note that what I am calling the “right-wing” in India is not only Hindu nationalists—the BJP and its supporters are not a coherent, unified group. In fact, the internal strands of the organisations in this network have vastly differing ideological roots (or, rather, where different strands of the BJP’s current ideology lean towards): it encompasses socially liberal libertarians; social and economic conservatives; firm believers in central governance and welfare for the “common man”; proponents of de-centralisation; followers of a World Bank inspired “good governance” where the state facilitates the growth of the economy; believers in a universal Hindu unity; strict adherers to the hierarchical Hindu traditionalism of the caste system; foreign policy hawks; principled sceptics of “the West”; and champions of global economic participation. Yet somehow, they all form part of the BJP–RSS support network. Mohan Bhagwat, the leader of the RSS, has tried to bridge these contradictions through a unified hegemonic discourse. In a column entitled “We may be on the cusp of an entitled Hindu consensus” from September 2018, conversative intellectual Swapan Dasgupta writes of Bhagwat: “It is to the credit of Bhagwat that he had the sagacity and the self-confidence to be the much-needed revisionist and clarify the terms of the RSS engagement with 21st century India...Hindutva as an ideal has been maintained but made non-doctrinaire to embrace three unexceptionable principles: patriotism, respect for the past and ancestry, and cultural pride. This, coupled with categorical assertions that different modes of worship and different lifestyles does not exclude people from the Hindu Rashtra, is important in reforging the RSS to confront the challenges of an India more exposed to economic growth and global influences than ever before. There is a difference between conservative and reactionary and Bhagwat spelt it out bluntly. Bhagwat has, in effect, tried to convert Hindu nationalism from being a contested ideological preoccupation to becoming India’s new common sense.” As Dasgupta lucidly attests, the project of the BJP encompasses not just political or economic power; rather, it attempts to wage ideological struggle at the heart of morality and common sense. There is no single coherent ideology, but different ideological intentions being played out on different fronts. While it is, at this point, difficult to see the pieces fitting together cohesively, the BJP is making an attempt to set up a larger ideological narrative under which these divergent ideas sit: fabricating a new understanding of belonging to the nation. This determines not just who belongs, but how they belong, and what is expected in terms of conduct to properly belong to the nation. I find two variants of the BJP’s attempts at building a new common sense through their think tanks: actively political and actively a-political. In doing so, I follow Reddy’s call to pay close attention to the different ‘vernaculars’ of Hindutva politics and anti-politics.[3] Due to the elite centralisation of policy making culture in New Delhi, and the relatively recent prominence of think tanks, their internal mechanisms have thus far been difficult to access. As such, these significant organisations of knowledge-production and -dissemination have escaped scholarly analysis. I fill this gap by examining the BJP’s attempt to build centres of elite, traditional intellectuals of their own through think tanks, media outlets, policy conventions, and conferences by bringing together a variety of elite stakeholders in government and civil society. Some scholars have characterised the BJP’s think tanks as institutions of ‘soft Hindutva’, that is, organisations that avoid overt association with the BJP and Hindu nationalist linkages but pursue a diffuse Hindutva agenda (what Anderson calls ‘neo-Hindutva’) nevertheless.[4] I build on these preliminary observations to examine internal conversations within these think tanks about their outward positioning, their articulation of their mission, and their outreach techniques. The double-sidedness of Hindutva acts as a framework for understanding the BJP’s wide-ranging strategy, but also to add to a comprehension of political legitimacy and the modern incarnation of ethno-nationalism in an era defined by secular liberalism. The BJP’s two most prominent think tanks (India Foundation and Chanakya Institute), show how the think tanks negotiate a fine balance between projecting a respectable religious conservatism along with an aggressive Hindu majoritarianism. These seemingly contradictory discourses become Hindutva’s strength. They allow it to function as a force that projects aggressive majoritarianism, while simultaneously claiming an anti-political ‘neutral’ face of civilisational purity and inter-religious inclusion. While some notions of ideology understand it as a systematic and coherent body of ideas, Hodge’s concept of ‘ideological complexes’ suggests that contradiction is key to how ideology achieves its effects. As Stuart Hall has shown, dominant and preferred meanings tend to interact with negotiated and oppositional meanings in a continual struggle.[5] Thus, as Hindutva becomes a mediating political discourse, it may risk incoherence, yet defines the terms through which the socio-political world is discussed. The BJP’s think tanks, then, attempt to legitimise its ideas and policies by building a base of both seemingly-apolitical expertise and what they call ‘politically interventionist’ intellectuals. Neo-Hindutva can thus be both explicitly political and anti-political at the same time: advocating for political interventionism while eschewing politics and forging an apolitical route towards cultural transformation. However, contrary to critical scholarship that tends to subsume claims of apolitical motivation within forms of false-consciousness or backdoor-politics, I note that several researchers at these organisations do genuinely see themselves as conducting apolitical, academic research. Rather than wilful ignorance, their acknowledgement of the organisation’s underlying ideology understands the heavy religious organisational undertones as more cultural than political. This distinction takes the cultural and religious parts of Hindutva ‘out of’ politics, allowing it to be practiced and consumed as a generalisable national ethos. [1] Nistula Hebbar, “At Mid-Term, Modi’s BJP on Cusp of Change.” The Hindu. The Hindu, June 12, 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/politics-and-policy/at-mid-term-modis-bjp-on-cusp-of-change/article18966137.ece [2] Anuradha Sajjanhar, “The New Experts: Populism, Technocracy, and the Politics of Expertise in Contemporary India”, Journal of Contemporary Asia (forthcoming 2021). [3] Deepa S. Reddy, “What Is Neo- about Neo-Hindutva?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 483–90. [4] Edward Anderson and Arkotong Longkumer. “‘Neo-Hindutva’: Evolving Forms, Spaces, and Expressions of Hindu Nationalism.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 26, no. 4 (October 2, 2018): 371–77. [5] Stuart Hall, “Encoding/decoding.” Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks 16676 (2001). by Gregory Claeys

Is utopianism an "ideology", in the loose sense of a coherent system of ideas, and if so where does it sit on the traditional spectrum of right-to-left ideas? Or does the "ism" merely describe a process of dreaming or speculating about ideal societies which in principle can never exist, as common language definitions usually imply? The former conception is relatively unproblematic, if too easily reduced to a psychological principle and then deemed deviant or pathological. Presuming the "ism" to imply the quest to attain or implement "utopia", however, we still encounter a vast number of often contradictory definitions, ranging from the common-language "impossible", "unrealistic", or without reasonable grounds to be supposed attainable, to "idealist" (as opposed to "realist"), to the "no-where" of Thomas More's original text, Utopia (1516), and its attendant pun, the "good place", or eutopia. Much confusion has resulted from inadequately separating these various definitions, two particular aspects of which, the non-existent/unreachable, and the realisable, are seemingly contradictory.

The "ism" is often divided today into three "faces", as Lyman Tower Sargent first termed them: utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice.[1] This typology is shared by another leading theorist, Krishan Kumar.[2] On this reckoning, one definition of utopian ideology would simply be utopian social theory, regardless of how we define the destination or ideal society itself, and whether it purports to be realistic or realisable, or remains an imagined ideal or norm which serves to inform action but which cannot be in principle be attained, because it continues to move forward even as its original vision comes to fruition. This approach allows us to describe every major ideology as harbouring its own utopia, or ideal type of self-realisation, while acknowledging the brand with varying degrees of reluctance. Modern liberalism, usually averse to the utopian label where it seemingly implies human perfectibility, might be supposed to entertain an ideal framed around free trade, private property, increasing opulence, and democracy.[3] Its most extreme form lies in the promise of eventual universal opulence. But it can extend further leftwards, for instance with the self-proclaimed utopian John Stuart Mill, towards socialism and much greater equality, as well as rightwards, with less state action to remedy inequality, as in libertarianism or neoliberalism.[4] Modern conservatism differs little from this, having yoked itself to commercial progress in the nineteenth century, though it sometimes retains deference to traditional elites, and greater aversion to democracy. Fascism certainly possesses utopian qualities, some rooted in the past and others in ideas of the future. Socialism inherits the Morean paradigm, with communism closer to More, and social democracy to liberalism. A specifically utopian ideology is thus more or less linked to More's paradigm of social equality, common property, substantial communal living, contempt for luxury, and a general practice of civic virtue. This can be termed utopian republicanism, and its origins traced to Spartan, Cretan, Platonic theory and Christian monastic practice.[5] Within this typology, to advert to Karl Mannheim's famous distinction in Ideology and Utopia (1936), we can also speak of utopianism having generally a critical function, and ideology a defensive one, vis-à-vis the status quo and class interest.[6] This involves a less neutral definition of ideology, not a system of ideas as such, but much closer to Marx's definition in the German Ideology (1845-6). These approaches to the utopian components in major ideologies are perfectly serviceable. They help to tease out the ultimate aspirations of systems of political ideas, as well as to reveal their whimsicalities and shortcomings. They give us a distinctive sense of More's paradigm of utopian republicanism, and of the continuity of one strand of political thought from Plato to Marx and beyond. They also reveal the more prominent role often played by fiction in the expression of utopianism compared to more overtly political ideologies. Nonetheless existing accounts of utopianism often leave us with two problems. Firstly, they do not reconcile the differences between the imaginary and realistic aspects of utopian ideals by adequately differentiating between the main functions of the concept. Secondly, they do not allow us to consider what the three "faces" share in common by way of content, or what the common goal of utopian movements, practices, and ideas alike might consist in. Let us briefly consider how these two problems might be solved.[7] Clearly ideal societies portrayed in literature and projected in social and political theory share much in common. Both are imaginary and textual, and sometimes only a thin veneer of fiction separates literary from theoretical forms of portraying ideas, particularly where "novels of ideas" are concerned. The chief definitional problem arises here from including the third, practical component. How should we categorise the content of utopian practice? That is, how do we describe what happens when people think their way of life actually approximates to utopia, rather than merely aspiring to it or dreaming of the benefits thereof? And how does this relate to the fictional and theoretical forms of utopianism? Utopian practice is usually conceived as communitarianism, or the foundation of intentional communities of mostly unrelated people who share common ideals. But it can also refer to other attempts to institutionalise the practices we associate with utopianism, most notably common or collectively-managed property, for example co-operation, or the promotion of solidarity in the workplace. Where the claim is made, we must cede to its proponents that what they practice is indeed a variant on the "good society", because they feel this is the case. That is to say, after a fashion, they have achieved, if only temporarily or conditionally, or in a relatively limited, perhaps "heterotopian", space, "utopia".[8] There is no contradiction between utopia possessing this realistic element and also implying the unrealisable if we concede that the concept serves a number of diverse purposes. It has historically had two main functions. One is to permit visionary social theory by hinting at possible futures on the basis of returning to lost or imaginary pasts, or extrapolating present trends to their logical conclusions. Once images of the Golden Age and Christian paradise served this purpose of providing an anchoring function, reminding us of what our original condition might have looked like, if for no other reason than to mock the follies and pretensions of the present and the fatuousness of any prospect of returning to a condition of natural liberty or primitive virtue. But from the late 18th century onwards utopianism began to turn towards future-oriented perfectibility, still conceived in terms of virtue, stability and social harmony, but now also more frequently linked to science and technology. So for the later modern period we can call this tendency towards imaginative projection the futurological function. By permitting us to think in terms of epochs and grand changes, the process allows us to burst asunder the bubbles of everyday life and push back the boundaries of the possible. It usually consists of one of two components. It may offer a blueprint, constitution, or programme which might actually be implemented. Or it may produce an image which allows us to criticise the present, but recedes like a mirage as we approach it, such that while we may realise past utopias we also constantly move the conceptual goal-posts, and our expectations of progress, forward. A second function of the idea of utopia is psychological, and is often addressed to explain the sources and motivation of utopian thinking. Here the concept satisfies an ingrained natural demand for progress or betterment, with which utopianism is often confused generically, and which corresponds to a personal mental space, a kind of interior greenhouse, in which the imagined improvements are conceived and nurtured. This function, associated with Martin Buber and even more Ernst Bloch, involves positing an ontological "principle of hope" or "wish-picture" where utopia functions to express a deep-seated longing for release from our anxieties.[9] This "desire" is sometimes regarded as the "essence" of utopianism.[10] This approach is often linked to religion, with which it has much in common, and in the early modern period with millenarianism in particular, and later with secular forms of millenarian thought. In Christianity both the Garden of Eden and Heaven function as ideal communities in which we participate at various levels. Our longings can be merely compensatory, alleviating the stress and anxiety of everyday life by positing a disappearance of our problems in any kind of displaced, idealised alterity. Here they may be non- or even anti-utopian, insofar as we wish our anxieties away by merely seeking distraction without social change. They may be satirical, mocking the pretensions of the wealthy and powerful. Or they may be emancipatory, demanding the alteration of reality to fit a higher ideal. This function permits escapism from oppressive everyday reality while also potentially fusing and igniting our desire for change. We can call this the alterity function, since it gives us a critical standpoint juxtaposed to our normal condition. Neither of these functions contradicts the prospect that utopia can be described as "nowhere" while also possessing a realistic dimension in communitarianism and other forms of utopian practice. They merely acknowledge the concept's multidimensional nature. This can be clarified further if we consider the problem of the content of utopianism, that is, the common normative core of the three "faces", and ask what utopian writers actually seek to realise when they actually propose restructuring society. This is easily portrayed if we remain within the loose parameters of the Morean paradigm. The existence of common property and a more communal way of life is the core of this ideal, and is shared by many forms of socialism and communism as well as many literary depictions of utopia, the best-known later modern example being Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888). Marx is of course its most famous non-literary expositor. Not all intentional communities have been communist, however. Charles Fourier, for example, proposed a reward for capitalist investors, who would receive a third, labour five-twelfths, and talent a quarter of any community's profits. Anarchist and individualist communities have sometimes promoted much less collectivist modes of organisation and social life than their socialist counterparts. But these still retain a core ideal which unites their "utopian" aspirations. All are clearly more egalitarian than the societies for which they purport to offer an alternative. They are also, or aim to be, much more closely-knit. They offer what sociologists from Ferdinand Tönnies onwards have usually referred to as a Gemeinschaft form of community, where social bonds are far stronger than in the looser and more self-interested Gesellschaft type of association which dominates everyday urban capitalist life. These more intense bonds constitute an "enhanced sociability", which epitomises utopian aspiration.[11] Normatively, utopia in general thus presents the ideal type of a much more sociable society, where something akin to friendship links many if not most of the inhabitants, and the aspiration to achieve it. But we need to give this shared content greater depth, specificity, and clarity. Not only are there many different forms of friendship, which exhibit varying degrees of solidarity, mutuality or altruism. It is readily apparent that merely consorting with others is not as such the aim of sociability. That is, we do not seek friendship, camaraderie, and other forms of intimate association and closer bonding purely for the sake of that connection, and merely out of loneliness or boredom, important though such motivations are. We aim rather at satisfying a deeper need, which can be described in terms of an elementary desire for "belongingness". This is the goal, usually conceived in terms of group membership, for which sociability is the means, and which utopian "hope" chiefly aims at. It can be described as the antidote to that alienation so often associated with the moderns, and which was at the core of the problematic the young Marx grappled with. But much of the rest of modern sociology, philosophy and political theory bears out the point. To the sociologists Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner, the "modern mind" has been described as typically a "homeless mind", a condition "psychologically hard to bear" which induces a "permanent identity crisis".[12] Buried under the blizzard of impulses modern urban life creates, moving frequently and thus often uprooted, isolated, driven apart by the dominant ethos of individualism and competition, we feel we have lost both a unity with our community and a wholeness in our inner selves. Longing to retrieve both, we search accordingly for symbolic places where we imagine we once possessed such unity. Here a Heimat - the German term evokes a richness and depth of feeling lacking in English - or "home", now lost to some other group, or just to time, easily becomes the focus of imaginary virtues, peace and fulfilment.[13] This can be projected backwards or forwards, as well as to distant locations or even outer space. Where homesickness or Heimweh lacks a definitive, objective past or place upon which to focus, it may be preferable to conceive our imaginary home as a future utopia, where Heimatslosigkeit, the feeling of loss, is conquered. If such a word existed, "homefulness" would define this domain. Another German term, Zusammengehörigkeitsgefühl, does part of the work of giving a sense of "togetherness" as well as belonging. "Belongingness" will do as well in English, and is a rich and somewhat open-ended concept which clearly invites greater scrutiny than is possible here. It enjoys a prominent position in modern group psychology, which is a key entry to point to the study of utopianism.[14] As elemental as "our need for water", Kelly-Ann Allen writes, it is so fundamental that its manifestations often passed unnoticed.[15] Some see the need to belong as the primordial source for our desire for power, intimacy, approval, and much else. It commences in infancy, drives our willingness to conform through life, and may haunt us in our dotage. It is reflected in an attachment to places as well as people, and extends by association to all our senses, including smell and taste. The sense of belonging or connectedness is a crucial component in solidarity, and is sometimes even portrayed as the basis of morality as such.[16] Everyone has experienced the anxiety of feeling alone, abandoned, ignored, friendless, rejected, shunned, dispossessed, displaced, foreign, alien, and alienated. Not being part of a group we aspire to join can be devastating. Exclusion cuts us to the bone. Not feeling part of a place also makes us uncomfortable and unwanted. By the effort to exclude others from the in-group, or "othering", belongingness can thus also play a fundamental role in the dystopian imagination.[17] So the aspiration for friendship, association, the feeling of neighbourliness, in a word belongingness, guides much of our behaviour through life. The condition of homelessness can inspire imaginary future ideal societies, and in utopian literary form has often done so during the past two centuries or so. But it also still often induces backward-looking perspectives. It "has therefore engendered its own nostalgias - nostalgias, that is, for a condition of 'being at home' in society, with oneself and, ultimately, in the universe".[18] This endangers more accurate and balanced accounts by encouraging a nostalgic rewriting of history, where we hearken back to an imagined superior past, and redact unpleasant facts which interfere with this vision. This process corresponds to an unfortunate desire, of which we have been reminded far too often in the past few years, to want to be told things which please us rather than those whose truths make us feel uncomfortable, and which we would rather ignore or forget. We are happy to be lied to if the lie makes us feel better, and rationalist conceptions of the inevitable conquest of error by truth are thus misguided where they fail to acknowledge this weakness. This process is aided by the fact that memory is often faulty and selective, and we can concoct an ideal starting-point without worrying about its accuracy. The further back we go, too, the poorer are the records which might contradict us. This makes propaganda the more readily successful. This has a bearing on one ideology more than any other. Nationalism in particular often depends heavily on and can indeed be defined as an "imagined community", in Benedict Anderson's well-known phrase, which makes it a distinctive form of utopian group.[19] It often adverts to periods when our nation was "great" and its enemies vanquished and subservient, and frequently demands a rewriting of history to accord with such narratives, as modern debates over imperialism and the statues of heroic conquerors and defenders of slavery make abundantly clear. To those not motivated by the search for more balanced stories, but who primarily seek ego reinforcement amidst their national identity crises, the glorious fictional history of the imagined nation is often preferable over its more likely inglorious and bloodstained real past. Whole nations feel a romantic nostalgia, "a painful yearning to return home", for their lost golden ages of innocence, virtue and equality, and for their mythical places of origin, or the peak of their global power and influence.[20] Denying the reality of the present and compensatory displacement are key here. But the same process occurs as nations age, become more urban and complex, and are more driven by capitalist competition, by consumerism and the anxiety to work ever harder. Personal relations suffer under all these forces. Increasingly, suggests Juliet B. Schor, we "yearn for what we see as a simpler time, when people cared less about money and more about each other".[21] Susan Stewart sees such nostalgia as a "social disease" which seeks "an authenticity of being" through presenting a new narrative, while denying the present.[22] We can readily see, then, that all major political ideologies advert to one or another glorious pasts or future images which recall or herald greater individual fulfilment, prosperity, and more powerful bonds of community. Not all address belongingness in the same manner, however. Liberalism tends from the early nineteenth century onwards to stress the value of individuality, and often under-theorises the need for and benefits of sociability.[23] Communitarian liberalism has made some effort to redress this omission, with varying degrees of success. Older forms of conservatism tended to locate the ideal state in the past and in more traditional systems of ranks, though this is not the case for more recent incarnations. Socialism is closest both semantically and programmatically to More's original utopian paradigm, and places great stress on the effort to rebuild communities around various artificially-constructed ideas of sociability and solidarity. To that inveterate critic of utopian aspiration, Leszek Kolakowski, Marxism-Leninism in particular shared a desire with all utopians "to institutionalize fraternity", adding that "an institutionally guaranteed friendship … is the surest way to totalitarian despotism", since a "conflictless order" can only exist "by applying totalitarian coercion".[24] To summarise the argument briefly presented here. What we can for short call the "3-2-1" definition of utopianism involves seeing the subject as possessing three faces or dimensions, utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice; two functions, that of providing a space of psychological alterity, and that of permitting the futurological dream of ideal societies; and one content, defined by belongingness. Utopianism is a stand-alone ideology insofar as it adopts variants on the Morean paradigm, but all major systems of ideas have utopian or ideal components which are used as reference points to suggest the goals of their systems. All forms of utopianism aim in particular at providing circumstances in which belongingness can be fulfilled. This ideal can be understood as the resolution of the central problem of alienation in modern life, an issue crucial to Marxism but equally to many other strands of modern social theory. The chief task now before us in the 2020s, to determine how it can achieve practical form in the face of the looming environmental catastrophe of the present century, can be addressed at another time. [1] Lyman Tower Sargent. Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 5. This typology dates from 1975, and is revised in Sargent's "The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited", Utopian Studies, 5 (1994), 1-37. See further Sargent's "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [2] Krishan Kumar. Utopianism (Open University Press, 1991). [3] On the aversion to adopting the utopian label, see David Estlund. Utopophobia. On the Limits (If Any) of Political Philosophy (Princeton University Press, 2020). Estlund argues that "a social proposal has the vice of being utopian if, roughly, there is no evident basis for believing that efforts to stably achieve it would have any significant tendency to succeed" (p. 11). [4] See my Mill and Paternalism (Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 123-72. [5] This typology is defended in my (and Christine Lattek) "Radicalism, Republicanism, and Revolutionism: From the Principles of '89 to Modern Terrorism", in Gareth Stedman Jones and Gregory Claeys, eds., The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 200-254. [6] See Lyman Tower Sargent. "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [7] I draw here on my After Consumerism: Utopianism for a Dying Planet (Princeton University Press, forthcoming). [8] This leaves aside the broader problem as to how far any ideal society rests on the labour or exploitation of some group(s), for whom the utopia of one group may thus become the dystopia of another. Decolonising utopia is an ongoing project. Some communes, like that founded by Josiah Warren in Ohio, have been called "Utopia". [9] See Martin Buber. Paths in Utopia, and Ernst Bloch. The Principle of Hope (3 vols, Basil Blackwell, 1986). Ludwig Feuerbach's idea of God as a projection of human desire, and of love as the essence of Christianity, formed the methodological starting-point for Marx's theory of alienation in the "Paris Manuscripts" of 1844. [10] Ruth Levitas. The Concept of Utopia (Syracuse University Press, 1990), p. 181. See also Fredric Jameson. Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (Verso, 2005). [11] An earlier version of this argument is offered in "News from Somewhere: Enhanced Sociability and the Composite Definition of Utopia and Dystopia", History, 98 (2013), 145-173. [12] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind. Modernization and Consciousness (Pelican Books, 1974), p. 74. [13] Its opposite is Heimatslosigkeit, which has no exact English equivalent, since "homefulness", sadly, is not a word and "homelessness" simply means being forced through poverty to live outside of a dwelling. Hence the use here of belongingness, despite its awkwardness. [14] It is acknowledged as such, however, chiefly in the literature on communitarianism. [15] Kelly-Ann Allen. The Psychology of Belongingness (Routledge, 2021), p. 1. [16] B. F. Skinner insists that "A person does not act for the good of others because of a feeling of belongingness or refuse to act because of feelings of alienation. His behaviour depends upon the control exerted by the social environment" (Beyond Freedom and Dignity, Penguin Books, 1973, p. 110). [17] See my Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 34-6. [18] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind, p. 77. [19] Benedict Anderson. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 1991). [20] Fred Davis. Yearning for Yesterday. A Sociology of Nostalgia (The Free Press, 1979), p. 1. [21] Juliet B. Schor. The Overspent American. Upscaling, Downshifting, and the New Consumer (Basic Books, 1998), p. 24. [22] Susan Stewart. On Longing (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), p. 23. [23] For a survey of this problem vis-à-vis John Stuart Mill, for instance, see my John Stuart Mill. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). [24] Leszek Kolakowski. Modernity on Endless Trial (University of Chicago Press, 1990), pp. 139, 143. The argument here turns largely on two assumptions, firstly that "human needs have no boundaries we could delineate; consequently, total satisfaction is incompatible with the variety and indefiniteness of human needs" (p. 138), and secondly opposition to "The utopian dogma stating that the evil in us has resulted from defective social institutions and will vanish with them is indeed not only puerile but dangerous; it amounts to the hope, just mentioned, for an institutionally guaranteed friendship". by Simon Julian Staufer

On 22 January 2021, Donald Trump’s term as President of the United States officially came to an end. Trump had been impeached and acquitted; had contracted and survived Covid-19; fought for re-election and lost, refused to accept the election outcome, and tried to overturn it. He had told supporters on January 6, the day the election results were certified, that “if you don't fight like hell, you're not going to have a country anymore,”[1] then watched as a mob of rioters broke into the Capitol in a last attempt to remake American history and secure him a second term; resulting in Trump being charged with incitement of insurrection, impeached for a second time, and finally acquitted once again, when his term had already expired.

All of this is very recent and very well-known history. The attack on the Capitol was the dramatic conclusion to four years that it can be described without hyperbole as the most turbulent and controversial single presidential term in American postwar history. It demonstrated in the starkest possible manner that Donald Trump was not only the most consistently unpopular US president since World War II[2], but that at the same time, he had built a devoted political base radical enough to physically try to stop a presidential transition by attacking a core institution of American democracy—even after Trump’s opponent had won as many electoral votes as Trump himself in 2016, clearly carried the popular vote and had his victory confirmed not just by the Electoral College but by judges and election officials across the nation, many of whom represented Trump’s own political party. Never in the country’s history had so many people turned out to vote for either giving a president a second term or ending his tenure.[3] ‘The people’ Donald Trump has very often been described as a populist, to the extent that the label can be considered widely accepted in describing his politics, his behaviour, and his approach. While driving out large numbers of voters either for or against oneself is not the definition of populism, it has been a result of Donald Trump’s style of both magnetising a large segment the voting population and repulsing another one. And if there is one element of a definition of populism that is universally acknowledged, it is its reference to ‘the people’—who, in the particularly turbulent final weeks of the Trump presidency were explicitly told that they had been robbed, and that election officials and judges were conspiring to misrepresent their will. But appealing to ‘the people’ is not sufficient to establish ‘populism’ in a meaningful sense. ‘The people’ can be a neutral term for any democratic politician’s constituency, and it seems safe to presume that every modern American president or presidential candidate has used it in some form. To understand how Donald Trump’s brand of politics is linked to the idea of populism as an approach to politics—and to study its relationship with recent events—it is worth looking at how we should define populism and what we should consider its key characteristics. Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders In 2018, in the earlier stages of Donald Trump’s term in office, I started researching Donald Trump’s success as a politician since the announcement of his presidential bid in June 2015, and the relative success of a politician at the other end of the left-right spectrum in American politics, Bernard (‘Bernie’) Sanders. While Sanders’s success never extended beyond good results in certain primaries and caucuses, it was still considered remarkable by many that a 74-year-old, self-proclaimed democratic socialist (who only joined the Democratic party temporarily to run for president) managed to win almost 2,000 primary delegates and move into the position of being a serious competitor to Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination for several months. Sanders accomplished a similar, if more short-lived, feat in 2020, leading the race for the Democratic nomination in its earliest stages. In 2016, Trump and Sanders campaigned on platforms that had little in common. Their ideas as to how to improve the economy—then, as in most election years, considered the most important issue by the American electorate—were radically different, as were their views on immigration, climate change, and a range of other topics. Yet the ‘populism’ label was applied liberally to both. Moreover, with the rise of many (purportedly) populist parties and movements in Europe in the 2010s, the story of Trump and Sanders, two ‘populists’ competing with ‘establishment’ figures like Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton, tied in with a broader debate about the state of democracy on either side of the Atlantic. Understanding populism Agreeing on the nature of populism, however, is tricky. While there is broad and systematic academic research into this topic, universal consensus on any aspect of it appears confined to the observation that political actors who can legitimately be deemed ‘populists’ in some way pit ‘the people’ against some other entity that they are opposed to. In addition, the notion is common—albeit not uncontested—that populism, whatever its exact nature, is systemically opposed to the tenets of a liberal democracy such as the United States, and much of the more recent research in populism studies has focused on actors on the far political right. On the other hand, there is no consensus on the nature of the entity the ‘people’ are juxtaposed with, on whether populism is a political ideology in its own right, and if not, on just what exactly it is. In a specifically American context, however, the term ‘populism’ predates contemporary usage and scholarship, and it is historically associated with the left-wing People’s Party of the 1890s, which championed smallholder farmers and labour unions. Only in the 1950s, in the era of what has come to be known as the Second Red Scare, aggressive campaigning against the alleged communist subversion of the United States put right-wing politics in the spotlight of the discussion about populism, and—as the historian Michael Kazin writes—‘the vocabulary of grassroots rebellion’ began serving ‘to thwart and revert social and cultural change rather than to promote it.’[4] On the other hand, politicians considered left-wing populists kept playing a major role in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, particularly in Latin America, with figures like Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales rising to prominence years after the end of the Cold War. This broad application across the political spectrum makes ‘populism’ even more elusive than it would be if applied chiefly to political movements on the contemporary right. It demonstrates that not only Donald Trump but also Bernie Sanders stands in a long tradition of politics associated with the concept. Their campaigning at the same time for the presidency during a timeframe of a little over a year—from 15 June 2015, when Trump announced his campaign, until 12 July 2016 when Sanders retired from the race—makes for an intriguing object of study in attempting to observe empirically whether, and to what extent, two politically fundamentally opposed actors can both be populists. If indeed two so wildly different actors should be populists, the question also arises whether the concept of populism may mean different things for different individual approaches to the political discourse. However, such research needs to first get back to the question of what populism in general is. Attempts to do so in academic studies have differed significantly. Ernesto Laclau[5] has constructed what is perhaps both the most wide-reaching and the most abstract theoretical framework for the topic, widely recognised for focusing on the essential characteristics of populism as such (rather than on elements only found in some forms of it) but also criticised for making it difficult to differentiate populism from other approaches to politics. An oft-cited alternative to dealing with this challenge is Cas Mudde’s definition of populism as a ‘thin-centred ideology’ based largely on a juxtaposition of ‘the people’ with an ‘elite’ against which populism rallies—which is thus malleable enough to fit a wide range of policy orientations and political platforms, while allowing for different types of mobilisation and political organisation.[6] However, applying the ‘ideology’ label to populism has been viewed rather critically by authors such as Michael Freeden, Donatella della Porta and Manuela Caiani, and Benjamin Moffitt and Simon Tormey[7]. Aiming to address the discussion on both populism’s ideational core and its amorphous nature, and to provide a foundation on which to build empirical research, I define populism as a political discursive logic whose normative ideational core is the juxtaposition of ‘the people’ as the group it claims to represent with one or several particular antagonists. This definition builds on a Laclauian approach but maintains that populism can be distinguished from other political discursive logics through this particular presentation of an antagonistic relationship, and of the people being the entity purportedly represented, rather than any other or more specific group (such as e.g. Christians, liberals, etc.). There are several elements of political discourse that can serve to express this relationship, which different populists may use differently. Based on the prior research in the field, I identified11 possible ways in which populism as a discursive logic articulates itself at the level of text (as opposed to non-textual or meta-textual levels such as the tone of speeches or visual elements of populists’ presentation), serving an instrumental function in expressing the people-antagonist dichotomy that lies at its core. The list of elements is not designed to exhaust all possibilities—and it bears stating that non-textual or even non-verbal elements would merit being studied through alternative or more extensive designs—but it is considered to feature most of what are considered populism’s most common traits on this level of analysis in the literature:

Two different kinds of populist Donald Trump’s and Bernie Sanders’s 2015 campaign announcement speeches were key elements of their political platform, as were two books written by them, or in their name, Great Again. How to Fix Our Crippled America (Trump) and Our Revolution (Sanders), both of which describe the platforms of their respective (attributed) author and their ideological positions and policy ideas.[8] The definition of and empirical framework for populism established was thus applied with a focus on this key discursive output in their campaigns. Speeches made by both candidates during the primary elections in 2016 were analysed to complement their books’ ideological content. The results offered new insight into the ideological malleability of populism, and into the challenge of pinning it down. The analysis found that both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders engage in a form of political discourse that features populist elements, but that they represent distinctly different approaches to articulating populism. Neither Donald Trump nor Bernie Sanders can be considered an ideal-type populist. For the discursive actions of both candidates during their respective 2015–2016 campaigns, some of the 11 elements identified were clearly present in the material analysed, some to a limited degree, and some, not at all. Both former presidential candidates’ discourse presented a normative juxtaposition of the people as a group with one or several antagonists, as has been considered constitutive for the definition of populism—in the case of Donald Trump, the antagonists are painted as external forces from countries like China, Mexico and Iran as well as politicians and bureaucrats whose most essential characteristic is incompetence in representing American interests against these outside forces; in the case of Bernie Sanders, the main antagonist is the ‘billionaire class’, whose schemes are aided and abetted by ‘establishment’ politicians from both major American parties. While Sanders makes a more explicit appeal to ‘the people’ and provides a more specific moral framework than Trump, a clash between populism and pluralism can textually be identified only in Trump’s discourse. Elements #6 and #7 of the framework—disregard for deliberative processes and a favourable view of swift executive action as well as promises of fast and wide-reaching change—are where Trump and Sanders differ most sharply. There is no evidence of these elements in Sanders’s speeches and book, and there is a substantial amount of evidence in Trump’s. Crucially, where in both the academic and the popular debate, especially in Europe, there is a tendency to equate ‘populism’ with the political far right, in a sense Bernie Sanders is more of a populist than Donald Trump—because his appeal to ‘the people’ is more explicit, reference to them as a group is more central to his discourse than to Trump’s, and the people-antagonist dichotomy is more clearly framed in normative terms. Populism and pluralism This finding has implications for the study of the relationship between populism and the political pluralism that is a fundamental tenet of liberal democracy. Considering that the people-antagonist conflict that forms the normative ideational core of populism is more clearly present in Bernie Sanders’s discourse than in Donald Trump’s, the idea seems questionable that populism, in and of itself, is at odds with liberal democracy, as proposed by a number of authors in populism research.[9] While this notion remains prevalent in the literature of authors seeking to establish definitions of populism that take account of its unique features vis-à-vis other political phenomena but are universally valid, other research has indeed claimed that, at the very least, a diverse electorate can be openly acknowledged by populists[10], and it may be that, even with a normative people-outgroup antagonism firmly in place, a denial of pluralism does not necessarily follow. Based on the example of Bernie Sanders, the argument could in fact be posited that populism can aim—or certainly profess to aim—at restoring the very mechanisms of liberal democracy that would make a campaign like that of Sanders unnecessary. The extent to which this correlates with Sanders’s position on the political left-right spectrum would be an interesting subject for further research on actors who position themselves similarly and use a similar, arguably populist discursive approach. What recent events have, in any case, emphatically demonstrated is how on the other hand a brand of populism that openly disdains institutionalism, multilateral decision-making and any opposition through the democratic process can unleash great destructive potential and have significant consequences for the stability of democratic institutions. The January 2021 storming of the United States Capitol is a stark reminder of that. [1] https://www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/donald-trump-speech-save-america-rally-transcript-january-6 [2] See also https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/ [3] This is true not only of the absolute number of voters but also of the percentage of the voting eligible population since the earliest data point available (the 1980 election), and of the percentage of the total voting age population since the 1960 election (when no incumbent ran). See https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/voter-turnout-in-presidential-elections for detailed statistics. [4] M. Kazin, The Populist Persuasion. An American History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 4. [5] See for example E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005). [6] See for example C. Rovira-Kaltwasser and C. Mudde, Populism. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). [7] See for example: M. Freeden, ‘After the Brexit referendum: revisiting populism as an ideology’, Journal of Political Ideologies 22(1) (2017), 1–11; M. Caiani and D. della Porta, ‘The elitist populism of the extreme right: A frame analysis of extreme right-wing discourses in Italy and Germany’, Acta Politica 46(2) (2011), 180–202; and B. Moffitt and S. Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style’, Political Studies 62(2) (2014), 381–97. [8] It may be noted that Donald Trump is reported to have employed a ghostwriter for his book, while Bernie Sanders is reported to have written his book himself. However, both books constitute textual output with which either respective politician is officially credited, to which he contributed, and which formalises his official positions and views. [9] See for example J.-W. Müller, ‘Populismus: Theorie . . . ’, in ibid. (ed.), Was ist Populismus? (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2017), pp. 25–67; and P. Rosanvallon, ‘The populist temptation’, in A. Goldhammer and P. Rosanvallon (eds.), Counter-Democracy: Politics in an Age of Distrust (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 265–73. [10] For a specific example and case study of ‘inclusive’ populism, see Y. Stavrakakis and G. Katsambekis, ‘Left-wing populism in the European periphery: the case of SYRIZA’, Journal of Political Ideologies 19(2) (2014), 119–42. by William Smith

Deliberative democracy has arguably become the dominant—perhaps even hegemonic—paradigm within contemporary democratic theory.[1] The family of views associated with it converge on the core idea that democratic decisions should be the outcome of an inclusive and respectful process of public discussion among equals. The paradigm has evolved considerably over the previous decades, with an initial emphasis on the philosophical contours of public reason gradually morphing into a more empirical analysis of democratic deliberation within a range of institutional and non-institutional settings.

The ideological assumptions underlying deliberative democracy have surprisingly not received much attention, either within the field of ideology studies or political theory. It is a mistake to approach deliberative democracy as an ideology in its own right, but the normative aspirations and empirical assumptions of its orthodox iterations are clearly informed by liberalism and social democracy. It takes from liberalism the idea of citizens as autonomous agents that are capable of engaging in a mutual exchange of reasons with their peers. It takes from social democracy a progressive aspiration to refashion, though ultimately not abolish, the institutional architecture of an ailing representative system. This ideological fusion can be seen, at least in part, as a reaction to the rise of new social movements and the resurgence of interest in civil society that accompanied the end of the Cold War. The deliberative paradigm emerged as an attempt on the part of thinkers such as Joshua Cohen, James Bohman, Seyla Benhabib, and—most influentially—Jürgen Habermas to steer liberalism in a more radical democratic direction, while insisting that emancipatory political projects must commit to the system of rights that underpin liberal constitutional orders. The relative lack of attention to the ideological moorings of deliberative democracy is unfortunate for at least two reasons. First, it diminishes our understanding of the rivalry between the deliberative approach and alternative theories of democracy. It is, for instance, difficult to fully grasp what is at stake in the debates between deliberative democrats and their agonistic, participatory or realist interlocutors without appreciating their underlying ideological differences. Deliberative opposition to a resurgent conservatism and the far right should also be understood as a manifestation of its ideological commitments, rather than a mere expression of technocratic distaste for anti-rationalist populism. Second, it clouds our view of the extent to which deliberative democracy is itself a site of ideological contestation. This is, at least in part, an upshot of internal tensions. The liberal influence on deliberative democracy heightens its concern for preserving order in the face of disagreement and conflict, such that achieving an accommodation between opposing societal perspectives is thought to take priority over the achievement of substantive political reforms.[2] The more overtly leftist and emancipatory social-democratic influence is a countervailing force, which motivates criticism of the status quo and support for political change notwithstanding the risk that this may exacerbate political divisions.[3] There is, though, another process of ideological contestation at work. This process is revealed when we turn our gaze away from, as it were, the ‘centre’ of the deliberative paradigm, toward developments at its ‘periphery’.[4] There have, in recent years, been numerous attempts to implement recognisably deliberative practices within settings that are radically different to liberal democratic regimes. The most striking, in many respects, are the experiments with deliberative mechanisms in regions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Officials have periodically experimented with custom-made deliberative forums, as well as importing mini-public designs pioneered elsewhere.[5] The ideological underpinnings of these developments are difficult to map, though the influence of the prevailing doctrines of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and ideas that can be associated with certain interpretations of Confucianism are evident. Baogang He and Mark Warren draw a connection between the use of deliberative forums in the PRC and a practice of consultation and elite discussion that has ‘deep roots within Chinese political culture’. They describe these experiments as instances of ‘authoritarian deliberation’, which is in turn presented as the core feature of a ‘deliberative authoritarianism’ that might serve as a potential pathway for political reform in the PRC.[6] The radical protest movements of the twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries have also emerged as unexpected but notable sites of deliberation.[7] The democratic practices of these movements have evolved through an iterated process of experimentation, spanning, among others, the women’s liberation movement, the New Hampshire Clamshell Alliance, the Abalone Alliance, ACT UP, Earth First!, the global justice movement, and the transnational wave of ‘Occupy’ movements. These movements are ideologically heterogenous, but anarchism is a particularly prominent influence on their politics, cultures, and internal practices. I contend that we can analyse these practices as a kind of ‘anarchist deliberation’, which corresponds to the emergence of ‘deliberative anarchism’ as a process of political mobilisation among decentred and autonomous movements.[8] There may be some reticence in referring to ‘deliberation’ in these authoritarian and activist contexts, rather than similar but distinct concepts like ‘consultation’ or ‘participation’. The concept is nonetheless salient, as the practices under consideration are constituted by the adoption of a ‘deliberative stance’ on the part of participants. This stance, as defined by David Owen and Graham Smith, requires agents to enter ‘a relation to others as equals engaged in mutual exchange of reasons oriented as if to reaching a shared practical judgement’.[9] The adoption of deliberative practices in various institutional or cultural settings is shaped, at least in part, through the various ways in which this core deliberative norm can be refracted through contrasting ideological prisms. In authoritarian deliberation, for instance, the egalitarian logic of deliberation is strictly limited to the internal relations of forum participants, against a systemic backdrop characterised by highly inegalitarian concentrations of power. Anarchist deliberation, by contrast, is an intersubjective practice among activists that is shaped by the core ideological values of anti-hierarchy, prefiguration, and freedom.[10] These values underpin a communicative process that is premised upon horizontal relations among participants recognised as equals, within autonomous spaces that emerge more-or-less spontaneously in the course of political mobilisation or mutual aid. These dialogic and expressive processes are instantiated within the networked organisational forms that have become synonymous with anarchist-influenced movements. Consensus decision-making is adopted within affinity group and spokes-councils as a means of both reaching decisions in the absence of hierarchy and prefiguring alternatives to the majoritarian procedures favored by parliamentary bodies. The consensus process is favoured because it is thought to amplify the voice of participants in various ways, allowing for the inclusion of diverse forms of expression against the backdrop of supportive activist cultures and shared political traditions. The deliberative process performs important functional roles in political environments where alternative coordination mechanisms are prohibited by ideological commitments. Authoritarian deliberation, for example, facilitates the expression and transmission of public opinion to elites in circumstances where open debate and multi-party elections are not permitted. Anarchist deliberation, by contrast, enables heterogenous protest movements to arrive at collective decisions about goals and tactics in the avowed absence of centralised or top-down power structures. The General Assembly (GA) in Occupy Wall Street (OWS), for instance, at least initially performed the functional role of allowing participants to clarify shared values, agree on processes, decide upon actions and discuss whether the movement should adopt ‘demands’.[11] The debates that occurred in the GA evolved into something of existential import for the movement, in that it was in and through the substance and symbolism of these large scale procedures that OWS forged a collective identity. The ideological underpinnings of deliberative practices inform their character and complexion, as well as attempts to ensure their operational integrity. Authoritarian deliberation, as the name suggests, is characterised by extensive control of issues and agendas by political elites, albeit with scope for citizen participation in selecting from a range of predetermined policy options. Anarchist deliberation, as one would expect, is characterised by extensive participant control over agendas and debates, though there are a range of informal cultural norms that aim to ensure the fairness and transparency of the process. These norms are typically seen as more flexible and organic than the more formal rules that lend structure to deliberation within mini-publics in authoritarian or democratic contexts. A recurring and much-discussed problem is nonetheless the emergence of informal networks of power and influence among activists, which tends to prompt much soul searching about whether more formalised rules or procedures should be adopted. David Graeber documents a particularly fraught meeting of Direct Action Network activists, where deep ideological divisions emerged over an apparently innocuous proposal to tackle gender inequalities in their ranks through the use of a ‘vibes watcher’ or ‘third facilitator’. These debates, he argues, may seem incomprehensible to outsiders, but are a matter of great significance to activists intent upon taming the corrosive influence of power while preserving the ideological integrity and ties of solidarity that underpin their political association.[12] The deliberative practices that emerge in authoritarian regimes and activist enclaves are treated as curiosities by deliberative democrats, but not as matters of primary concern. This is, for the most part, because neither authoritarian deliberation nor anarchist deliberation exhibits any sort of connection to democracy as it is understood within mainstream deliberative theorising. The extent to which ideas and practices associated with deliberative democracy can be adapted within authoritarian regimes and radical activist networks nonetheless demonstrates the ideological fluidity of the broader paradigm. It is, in fact, possible to place the deliberative views discussed here on an informal spectrum. Each view affirms deliberation as an optimum means of generating collective opinions or arriving at collective decisions, though each takes its bearings from contrasting assumptions:

This spectrum captures the contrasting ideological influences shaping deliberative practices across diverse political and cultural contexts, enabling us to tease out interesting similarities and differences. Deliberative authoritarianism and deliberative democracy, for instance, converge in treating deliberation as a discursive practice that should exert a positive influence on state institutions at local or national levels, albeit with diametrically opposed visions of how state power should be constituted. Deliberative anarchism, by contrast, tends to resist any association with authoritarian or liberal democratic institutions, adopting an antagonistic and insurrectionary orientation toward state and non-state sources of hierarchy. There are, to be sure, profound challenges confronting each of these perspectives, such that there must be at least some doubt about their future prospects. Deliberative authoritarianism, for instance, appears to be far less viable as a developmental pathway for the PRC in light of the recent tightening of political controls under the premiership of Xi Jinping.[14] Deliberative democracy retains considerable hold over the imaginations of democratic theorists, but it is not clear whether and how it can shape democratic practices in an era of post-truth politics and increasing polarisation. Deliberative anarchism, for its part, may suffer from an ongoing fall-out from the various movements of the squares, which has seen intensifying criticism of a perceived tendency among radical activists to fetishise process over outcomes.[15] There are, notwithstanding these challenges, at least two lessons that we can take from setting out this informal spectrum of deliberative positions. First, it illustrates the reach and appeal of deliberation across contrasting political traditions. In other words, the basic idea of deliberation as a means of including persons in a common enterprise, pooling their experiences and perspectives, and arriving at collective views or decisions appears to cohere surprisingly well with a broad range of political ideologies and frameworks. This should temper superficial critiques of deliberation that casually dismiss it as a creature of liberal political morality. Second—and I think more significantly—it reveals the contingency and contestability of the ideological basis of deliberative democracy in progressivist liberalism and social democracy. Deliberative authoritarianism and deliberative anarchism may not, in the end, pose an enduring challenge to mainstream interpretations of deliberative democracy, but their emergence nonetheless demonstrates that alternative iterations of its core ideas are possible. This should again give pause to those who are too quick to criticise the paradigm as inherently wedded to a broadly reformist or even quietist outlook. It should also, conversely, guard against political complacency on the part of its adherents, standing as a permanent reminder that tethering the idea of public deliberation to the political and institutional horizons of the present is neither necessary nor—perhaps—desirable.[16] [1] A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). [2] M. Freeden, The Political Theory of Political Thinking: The Anatomy of a Practice, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 219-222. [3] M. A. Neblo, Deliberative Democracy Between Theory and Practice, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 36. [4] J. Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, trans. W. Rehg, (Cambridge: Polity, 1996). [5] W. Smith, ‘Deliberation Without Democracy? Reflections, on Habermas, Mini-Publics and China’, in T. Bailey (Ed.), Deprovincializing Habermas: Global Perspectives (New Delhi: Routledge, 2013), pp. 96-114. [6] B. He and M. Warren, ‘Authoritarian Deliberation: The Deliberative Turn in Chinese Political Development’, Perspectives on Politics, 9 (2011), pp. 269-289. He and Warren discuss numerous examples of deliberative consultation at local or regional levels in the PRC, such as the use of deliberative polling to establish budgeting priorities in Wenling City. These mini-publics are comprised of ordinary citizens allowed to select policy recommendation after a structured process of deliberation, but their agenda and remit remains under the control of local CCP officials. [7] F. Polletta, Freedom is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements, (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2002). [8] W. Smith, ‘Anarchist Deliberation’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 27:2 (2022), forthcoming. [9] D. Owen and G. Smith, ‘Survey Article: Deliberation, Democracy, and the Systemic Turn’, Journal of Political Philosophy, 23 (2015), pp. 213-234, at p. 228. [10] B. Franks, N. Jun and L. Williams (Eds), Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach, (London: Routledge, 2018). [11] N. Schneider, Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013), pp. 56-64. [12] D. Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography, (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2009), pp. 336-352. [13] He and Warren, ‘Authoritarian Deliberation’, p. 269. [14] L‐C. Lo, ‘The Implications of Deliberative Democracy in Wenling for the Experimental Approach: Deliberative Systems in Authoritarian China’, Constellations (2021), https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12546 [15] M. Fisher, ‘Indirect Action: Some Misgivings about Horizontalism’, in P. Gielen (Ed.), Institutional Attitudes: Instituting Art in a Flat World, (Valiz: Amsterdam, 2013), pp. 101-114. [16] I’d like to thank Marius Ostrowski for the invitation to write this post for Ideology Theory Practice and for his generous comments on the initial draft. by Glyn Daly

What can porn shoots tell us about the functioning of ideology? This can be approached through a critique of externalism. In externalist thinking there is always the image of a full presence, something substantial to which all distortion can be referred. In modern discourse, this is ultimately the position occupied by the (mythic) phallus: an autonomous self-sustaining One that stands apart and effectively overdetermines all relations of distortion: desire, narcissism, envy, and so on as so many orientations toward it.[1] Put in other terms, it reflects Jacques Derrida’s critical charge of phallogocentrism—where the symbolic order tends always to centre on notions of (masculinised) presence and identity—that he levels against psychoanalysis.[2] But what this misses is the way in which the privileging of the phallus in psychoanalysis is simultaneously a non-privileging. What the phallus names in psychoanalysis is essentially movement and/or treachery: gaining an erection when one least wants it and losing it when it is most required. Far from any autonomy or positivity of presence, the phallus reflects an autonomy of negativity. In other words, the phallus is “privileged” only insofar as it signifies lack as such. This is why Jacques Lacan repeatedly refers to the phallus as a “wanderer” and as “elsewhere”: that which denotes a permanent alibi at the very heart of the symbolic order. Indeed the whole of psychoanalysis can be seen as predicated on the basic absence not only of phallic consistency (a phallogo-decentrism in this sense) but also all externality.