|

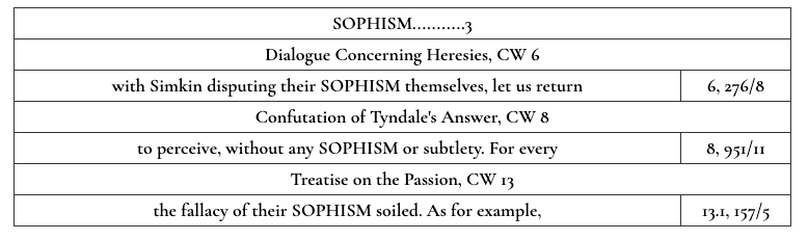

17/4/2023 (Re)inventing the nation on the centenary of the Turkish Republic: A Rhetorical Political Analysis of Erdogan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’Read Now by Arife Köse

History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogeneous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now [Jetztzeit].

- Walter Benjamin - On 28 October 1923, dining with his friends, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is said to have declared ‘Gentlemen! We are going to announce the Republic tomorrow.’ The next day, he proclaimed the following law: ‘The form of government of the Turkish state is the republic.’[1] Once the law passed by the Turkish Parliament later the same day, the State of Türkiye as republic, which is now a century old, came into being. From one perspective, that date—29 October 1923—is just a place on the calendar, ‘chronos’, or quantitative time. However, as Benjamin argued, calendars are also ‘monuments of historical consciousness,’[2] marking out moments of what rhetoricians call ‘kairos’—measuring not quantity of time but a quality of timely action. Kairos points to the ‘interpretation of historical events’ because it is about the significance and meaning assigned to them.[3] It is also about the opportunity to be grasped now for action that cannot be grasped under different conditions or situations. Thus, kairos always has an argumentative character since the significance given to historical events are always contested and temporarily decontested in specific ways. In this respect, due to the significance and meaning assigned to it, the foundation of the Turkish Republic can be understood as a moment when ‘chronos is turned into kairos’.[4] Now, 100 years since its foundation, the country’s incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is seeking to create a moment of kairos again, using it to reinvent the idea of ‘Turkishness’ itself and to turn it into a time of action in the service of continuity of his rule. This is a rhetorical act that requires ideological analysis. In this article, I examine how Erdoğan fulfils such a rhetorical act through Rhetorical Political Analysis (RPA) of the speech he delivered on 28 October 2022. This speech was intended to set forth his vision for the future of the country on the day that the Turkish Republic entered its centenary and was entitled a ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. I will begin by providing some historical and theoretical background, followed by a rhetorical analysis of his political thinking around the centenary. My argument is not only that his ideological thinking shapes his actions but also his understanding of Turkishness in the context of the centenary is shaped by his strategic action, aiming at winning the elections in Türkiye in 2023 and consolidating his and his party’s leadership position in the future. Background As 29 October 2023 marks the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Erdoğan, as both President of Türkiye and leader of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), delivered a speech on 28 October 2022 to set out the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’. The gathering was held in the capital Ankara, in Ankara Sports Hall which accommodates 4,500 people. 11 political parties were invited to the event. The only party that was not invited was the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), the Kurdish-led, left-wing party which has been denounced by Erdoğan as a ‘terrorist’ entity due to its alleged connection with PKK, the Kurdish paramilitary organisation. Alongside the political parties, AKP Members of Parliament, mayors, party members, and supporters were invited to the event—as well as some artists, NGOs, academics, and journalists (unusually including notable dissident journalists). The event, at which Erdoğan spoke for 1 hour 40 minutes, lasted 2 hours overall.[5] Like the morphological approach to ideological analysis pioneered by Michael Freeden,[6] rhetorical approaches to ideologies start from the position that political ideologies are ubiquitous, and a necessary part of political life. However, unlike morphological analysis, they focus on ideological arguments rather than ideological concepts, on the grounds that ideologies are ‘shaped by and respond to external events and externally generated contestation from alternative ideologies’.[7] Accordingly, Alan Finlayson suggests using RPA to analyse ideologies, in order to pay attention not only to the semantic and structural configuration of ideologies but also to political action, such as the strategies that political actors develop to intervene in specific situations. Further, RPA focuses on the performative aspect of political ideologies by drawing attention to how performativity becomes part of the morphology of the ideology in-question through foregrounding specific political concepts.[8] Alongside the concepts provided by the rhetorical tradition, RPA also draws on kinds of proof classically categorised as ethos, pathos and logos.[9] Whereas ethos indicates appeal to the character of the speaker with whom the audience is invited to identify, pathos is about appeal to the emotions. Lastly, logos indicates appeal to reason by political actors in their attempt to have the audience reach particular conclusions by following certain implicit or explicit premises in their discourse. Overall, RPA commits to the analysis of politics ‘as it appears in the wild’.[10] The rhetorical situation Analysis of political speeches begins with the analysis of the rhetorical situation, since every political speech is created and situated in a particular context. In this respect, every political speech, alongside its verbal manifestation, performs an act by intervening in a particular situation.[11] Those situations are characterised by both possibilities and restrictions for the orator, and it is one of the primary characteristics of skilled orators to know how to employ the opportunities and overcome the restrictions embedded in the situation. In such situations, political ideologies are not only deployed by political actors to intervene in and shape the situation, but they are also shaped through the act of intervention when addressing the challenges or trying to persuade others of a particular action. In the case of Erdoğan’s ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ there are two exigencies: first, for him, it is a moment of kairos to be grasped and put in the service of his strategic aim of winning the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023. For this, evidently, he needs to prove to the people beyond his supporters that he is the leader of the whole country who can carry it into the future. Thus, it is an opportunity for him to amplify his rule as President of Türkiye, which is a position that he gained as a result of regime change in Türkiye 2017. On 16th April 2017, Turkish voters approved by a narrow margin constitutional amendments which would transform the country into a presidential system. This was followed by the re-election of Erdoğan as the President of the country on 24 June 2018 with the support of MHP (Nationalist Movement Party). Since then, AKP and MHP work together under the alliance called People’s Alliance. The new system has been widely criticised on the grounds that it weakens the parliament and other institutions and undermines the separation of powers through politicisation of the judiciary and concentration of executive power in a single person. Overall, this has led to an increasingly authoritarian governance.[12] The second exigency for Erdoğan is the enduring economic crisis from which the country has been suffering since June 2018. In that year, as a result of Erdoğan’s insistence on lowering interest rates, Türkiye experienced an economic shock, resulting in a dramatic loss in the value of Turkish Lira against Dollar. Since then, three Turkish Central Bank governors have been successively dismissed by Erdoğan. For example, in March 2021, Erdoğan fired then governor Naci Ağbal after he hiked the interest rates against Erdoğan’s persistence on not increasing them no matter what. Erdoğan replaced him with Şahap Kavcıoğlu, known for his loyalty to Erdoğan. Such a move made the economic situation in Türkiye even worse. One of the economic commentators in the Financial Times wrote, ‘Erdoğan’s move leaves little doubt that all the power in Türkiye rests with him, and this will result in rate cuts. This will simply make Türkiye’s inflation problem even worse.’[13] The overall consequence of this turmoil has been rising prices as the Lira collapsed and wages remained stagnant, causing a dramatic drop in people’s purchasing power. By August 2022, according to research, 69.3 percent of the Turkish population were struggling to pay for food.[14] In November 2022, after Erdoğan delivered the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’, the inflation rate reached 85.5%.[15] Erdoğan had to address these two exigencies while he was under heavy criticism not only from international actors and his national opponents but also from the rank and file of his own party about Türkiye’s economy and democracy. His leadership has also been weakening for some time. Erdoğan’s loss in the two big municipalities—Ankara and Istanbul—in the local elections in 2019 exposed the myth that he is a leader who never loses an election. This was the context in which the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ event was held. It was a kairological moment for Erdoğan, where he attempted to reinvent Turkishness and decontest its meaning through an ideological speech-act manifested through various rhetorical moves to position him and his party as the only option in the upcoming elections. The arrangement of the speech Political speeches are significant for the analysis of ideologies not only because of what political leaders say but also because they provide us with the opportunity to observe how the political leader in-question, the nation, and the audience are positioned both in the speech and on the stage. Therefore, paying attention to the arrangement of the speech is as important as the text of the speech. ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ begins with a performance including video clips with narrations, dance performances, songs, and poems. The decoration of the hall can also be thought of as part of this performance. This part of the event can be considered as what is called the ‘prologue’ of the speech in the rhetorical tradition and is also part of ideological analysis. The second part of the event consists of Erdoğan’s speech, where he begins by saluting people in the hall and then praising the Republic and those who fought in the War of Salvation for five minutes. He talks for 35 minutes about the significance of the AKP in the context of the centenary by explaining what it has achieved so far. Following this, he drones on about his party’s achievements by marshalling the services provided by the AKP under his leadership, which lasts for about 20 minutes. After that, he talks about his promises for the ‘Century for Türkiye’ for 20 minutes. In the closing section of the speech, he asks everyone in the hall to stand up and take a nationalist oath with him by repeating his words: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be great! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ In sum, the whole speech consists of two main parts of which the first is about glorifying the Turkish nation and the second part is primarily concerned with the AKP and Erdoğan himself. The speech is therefore arranged in a way which conflates the nation with AKP and Erdoğan and argues for an indispensable bond between them. History without contingency The event begins with a narration by a male presenter accompanied by sentimental music, speaking about the ‘limitless’ and ‘mystical’ universe that operates with self-evident ‘balance’ and ‘order’. We are told that all we do is ‘to find our place within this universe’, and ‘whatever we do, do it right’. Then, around 25 people representing different age groups, genders, and occupations stage a dance performance, embodying the Turkish nation: comprised of a variety of people yet performing the same movements harmoniously under the same flag. In this part, first and foremost, the Turkish nation is situated in its place in time and history. We only hear a narration without seeing the actual person speaking and this narration is accompanied by a video show. The voice asks us to commence history with ‘the moment that the horizon was first looked at’; with the moment that ‘the humanity became humanity’. Within this transcendental history whose origin is undeterminable, the beginning of the Turkish nation is also rendered ambiguous. We are told: If you are asked when this journey began, your response should be ready: When the love of the homeland began! Thus, the origin of Turkish nation is situated into a self-evident kairos without chronos as if its existence is free from the contingent flow of events throughout history. This arrest of contingency is further amplified through the topos of a ‘nation who always does the right thing’: You had forty paths, and maybe forty horses too. If you had not chosen the right thing, you would not have been able to arrive at your homeland, today, now. You chose the right thing even if it was the hard one. Moreover, according to the narration, Turkish nation is a nation which acts now through considering the future; thus, its now is always oriented to the future: You have always envisaged tomorrow. Your history has been written with your choices. Hence, the future also means you. Here we see a nation that always knows what it is doing, always does the right thing and has the power to shape history through the choices it makes. Its actions are always determined by its vision for the future and its future is not contingent but is destiny; a ‘journey’ with its own telos. Then, the narrator asks, ‘when does the future begin?’ and adds, ‘this is the biggest question. The most important question is where the future begins.’ But, this time, we are not left in ambiguity. We are told that it begins ‘here,’ ‘today,’ ‘now’. Strikingly, today is only meaningful as a point of beginning of the future. Hence, our present is also arrested by both our past and our future. We do not have the right to choose our own kairos—our right time for action for a future that is designated by us—but are destined to conform to the already designated kairos for us within, again, already designated chronos: our possibility to have alternative ‘now’ and alternative ‘future’ is taken from us. The ethos of Turkishness Such an articulation of transcendental Turkishness with time and history is amplified with the further delineation of the ethos of the nation. Accordingly, for Erdoğan, the Turkish nation consists of ‘siblings’ who are united under and through the same ‘crescent’—the crescent on the Turkish flag. This is a nation who has the courage and strength to challenge the entire world. Connoting the lyrics of Turkish National Anthem, the lyrics of one of the songs that performed in the event reads: Who shall put me in chains Who shall put me in my place. Then the song continues by saying: There is no difference between us under the crescent We are not scared of coal-black night We are not scared of villains Nevertheless, nowhere in the speech are we told who those ‘villains’, or people who want to ‘put us in chains’ are. Although they cannot stop us from our way, we are expected to consider their existence when we act. Here, we see the manifestation of the ethos of Turkishness through its association with the concepts of freedom, understood as sovereignty, and the Turkish flag. Türkiye is presented as a nation where differences between its members perish under the uniting power of the Turkish flag, and when acting, it always prioritises the protection of its sovereignty. Furthermore, it is argued, the most definitive characteristic of the Turkish nation is that it never stops; it is always in motion, walking towards the future. Thus, the current Turkish Republic constitutes just a small part of its ‘thousand years of life’ so far. However, the Republic is important because it proves what the Turkish nation is capable of: it can achieve the unachievable, and it can overcome the toughest obstacles. But Turkish nation’s ambitions cannot be limited to the current Republic, and no matter how much it suffers now it must keep moving towards the future. In his speech, Erdoğan also uses the metaphor of a bridge, which can be thought together with this topos of ‘nation in motion’. He says, ‘We will raise the Turkish Century by strengthening the bridge we have built from the past to the future with humanistic and moral pillars’. Here, the ‘bridge’ signifies the uninterrupted continuity between past and future built by Erdoğan and his party, where the present is only characterised as a transition point in the ‘journey’ of the Turkish nation towards the future. The performative construction of Turkishness is also accompanied by its articulation with its state, flag and homeland which are the core concepts of Erdoğan’s nationalism that he summaries with the motto ‘one nation, one flag, one state, one homeland.’ For example, in the middle of the hall, there is a huge sundial hanging from the roof, and there is a huge star and crescent on the floor under it that represent the Turkish flag and the homeland. Furthermore, there are 16 balls hanging around the sundial, representing the 16 states founded by Turks throughout history. In Erdoğan’s political thinking, ‘one nation’ signifies indivisible community where the nation is characterised by its ethnic and religious origins- namely being a Turkish and Sunni Muslim. ‘One flag’, on the other hand, signifies the Turkish flag, consisting of red representing the blood of martyrs killed in the Turkish War of Independence, and the white crescent and the star representing the independence and the sovereignty of the country. While ‘one homeland’ represents the land of Türkiye, ‘one state’ signifies the powerful and united Turkish state. The role of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) So far, we have been told who we are, where we are coming from and where we are going, and now, the stage is Erdoğan’s. Erdoğan’s speech consists of three points: situating his party and himself within the history of the Republic by explaining what they have done so far, emphasising his role in this process, then, explaining his promises for the next ‘Century for Türkiye’. For Erdoğan, the AKP is the guarantee of continuity between the past and the future. Accordingly, after beginning his speech by praising Atatürk and the people who fought in the War of Independence, he continues by saying: Of course, there were good things initiated in the first 80 years of our Republic, some of which have been brought to a conclusion. However, the gap between the level of democracy and development that our country should have attained and where we were was so great. Then AKP came into power, his story goes on, and ‘made Türkiye bigger, stronger and richer’ despite all the ‘coup attempts’ and ‘traps’. It was the AKP who actualised ‘the most critical democratic and developmental leap with common sense, common will and common consciousness going beyond all types of political or social classifications’ by including everyone who has been oppressed and discriminated in Türkiye, from Kurds to Jews. Hence, we are told, it is the AKP who will build the Century for Türkiye through the ‘bridge that it establishes from the past to the future’. The ethos of Erdoğan Erdoğan also positions himself as the leader who has brought Türkiye up to date and, thus, the person who can take it into the future. Erdoğan claims that today he is there as a ‘brother’, ‘politician’, and ‘administrator’, as someone who has devoted all his life to the service of his country and the nation. He emphasises that he is there with the confidence that stems from his ‘experience’ in running the country. He then situates himself within other significant or founding leaders in Turkish history by saying, I am here, in front of you with the claim of representing a trust stretching out from Sultan Alparslan to Osman Bey, from Mehmet the Conqueror to Sultan Selim the Stern, from Abdulhamid Han to Gazi Mustafa Kemal. Thus, he is not only one of the leaders in the 100 years of the Turkish Republic but is part of a line of leaders beginning with Sultan Alparslan who led the entrance of Turks to Anatolia with the Battle of Malazgirt in 1071. Moreover, for him, We are at such a critical conjuncture that, with the steps that we take, we are either going to take our place in the forefront of this league or we are going to be faced with the risk of falling back again. This is the task awaiting the leader, one that is so crucial and important that it cannot be undertaken by just any leader. It requires, first and foremost, experience. As proof of his and his party’s level of experience and ability to undertake big and important tasks, he reels off a lengthy list of services provided by the AKP under his leadership in the last 20 years. He gives detailed figures from education, health, transportation, sport etc., such as how AKP has increased the number of classrooms from 343,000 to 612,000, or the number of airports in the country from 26 to 57, or the gross domestic product from 40 billion Lira to 407 billion Lira. Thus, he seeks to close the debate around his way of governance and leadership by depoliticising the discussion through relying on inarguable statistics. Then, he again draws attention to the experience when at the same time emphasising the inexperience of the opposition in running the country and warns, ‘if we do not continue our way by putting one work on top of another one, it is inevitable that we are going to vanish’. Consequently, as happened during the process that led to the independence of Türkiye and the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago, we are put in a position of choosing between two options, this time presented by Erdoğan: either we are going to do the right thing, or we are going to disappear. Concepts of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ Then, Erdoğan moves onto explaining the ‘spirit’, ‘philosophy’, and ‘essence’ of the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ that he suggests as a vision for future not only to Türkiye but to the entire world and humanity. He summaries the Vision with 16 core concepts—namely, sustainability, tranquility, development, values, power, success, peace, science, the ones who are right, efficiency, stability, compassion, communication, digital, production, and future. At the core of those 16 concepts lies the claim and promise to make Türkiye a great regional and global power. Such an assertion consists of two dimensions: first, liberal economic developmentalism, which has a prominent place in the Turkish neoliberal conservative political tradition and is structured around the adjacent concepts such as growth, progress, investment, and enhancing competitive power. For example, Erdoğan says, We will make Türkiye one of the largest global industrial and trade centres by supporting the right production areas based on advanced technology, with high added value, wide markets, and increasing employment. According to Erdoğan, the second dimension of making Türkiye great consists of security and stability. For him, Türkiye has become a global and regional power under his rule thanks to the stability and security guaranteed by the presidential system that came into force in 2017. The continuation of this power, he argues, depends on the maintenance of this security and stability, which is also the guarantee for a continuously prosperous economy and the provision of more work and service to the country. When doing this, for him, we are also responsible for the protection of the values belonging to the whole of humanity—not only the Turkish nation—thus we will also ensure ‘cultural and social harmony’. When considered together with the whole speech, this section conforms with Erdoğan’s understanding of Turkishness articulated with himself and his party. According to the reasoning that we are asked to follow throughout the event, instead of being occupied with the present infrastructural problems of the country that have led to the deterioration of the economy and democracy, our thinking and actions must always be future-oriented. In this respect, for example, what matters is not the present economic situation but the economy in the future as presented in the Vision. We might be starving and struggling to continue our daily lives yet still we should continue growing, competing with our rivals, and building bridges and airports. And such a shining future cannot be arrived through change and but only through security and stability ensured by the leadership of the ‘right man’. Then, he makes a call to ‘everybody’ to contribute to the ‘Century for Türkiye’, to ‘discuss’ it, to ‘put forward proposals’, and to ‘create’ and ‘build’ the vision for a Century of Türkiye together. However, it is not clear how people are to contribute to the ‘Vision for a Century of Türkiye’ when our past, present, and path to the future are turned into a destiny where we are not agents but prisoners. In fact, such a tension between the closure and opening of the political space can be witnessed throughout the whole speech. For example, Erdoğan says, Today we have come together for the promise of strengthening the first-class citizenship of the 85 million, except the ones committing hate crimes, crimes of terror and crimes of violence. Here, he draws his antagonistic boundaries around who is included and excluded from the nation. When doing this, he uses tellingly vague terms such as ‘crimes of terror’, which can potentially include anyone depending on how far the definition of ‘terror’ becomes stretched. However, despite this, he promises ‘to put aside all the discussions and divisions that have polarised our country for years and damaged the climate of conversation that is the product of our people's unity, solidarity and brotherhood’. This should be understood as part of his effort to secure his existence in the future of the country as the leader of the whole nation, yet still seeking to do this by persuading people of his way of doing politics. Here, the art does not lie in the total closure and opening of the political space but in the ability to convince people that he is the leader who can do both any time he sees convenient—this is a crucial dimension of Erdoğan’s leadership style. Finally, he ends the speech with an oath as he usually does. He asks around 5,000 people in the hall stand up and repeat his words after him: ‘One nation, one flag, one homeland, one state! We shall be one! We shall be big! We shall be alive! We shall be siblings! Altogether we shall be Türkiye!’ This is his signature; thus, the speech has been signed. Conclusion Erdoğan’s nationalist political thinking in the context of the centenary of the Turkish Republic is shaped by his particular way of intervening in the political situation and has become part of his strategic action. Erdoğan employs the centenary to assert the continuity of his and his party’s leadership by establishing an analogical continuity between the foundation of the Turkish Republic 100 years ago and his leadership today. He turns the kairological moment in the past into his kairological moment for himself. He does this by articulating Turkishness, time and history in a way that enables him to situate himself and his party as the only figure that can guarantee such continuity on which the existence of Turkish nation depends—otherwise, we are going to ‘vanish’. Returning to Benjaminian analysis, Erdoğan takes a ‘tiger’s leap into the past’[16] to establish such continuity, however, as history has also shown us, there is a limit for every jump. [1] I quoted this phrase from the amended version of the Turkish Constitution in 1923 known as Teskilat-i Esasiye Kanunu. The Constitution can be reached from: TESKILATI_ESASIYE.pdf (tbmm.gov.tr), p. 373. [2] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, pp. 264. Jonathan Cape. [3] Smith, J. E. (2002). ‘Time and Qualitative Time’, in Sipiora, P. and Baumlin, J. S. (eds.), p. 47, Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in History, Theory and Praxis, pp. 46-57. State University of New York Press. [4] Ewing, B. (2021). ‘Conceptual history, contingency and the ideological politics of time’, in Journal of Political Ideologies, 26:3, p.271. [5] Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan "Türkiye Yüzyılı" vizyonunu açıkladı - YouTube [6] Freeden, M. (1996). Ideologies and Political Theory. Clarendon Press. [7] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.757. [8] Finlayson, A. (2021). ‘Performing Political Ideologies’, in Rai, S. (ed.) et al, The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance, pp. 471-484. Oxford University Press. [9] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, pp. 751-767. [10] Finlayson, A. (2012). ‘Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies’, in Political Studies. 60:4, p.751. [11] Martin, J. (2015). Situating Speech: A Rhetorical Approach to Political Strategy. Political Studies, 63:1, pp. 25-42. [12] Adar, S. and Seufert, G. (2021). Turkey’s Presidential System after Two and a Half Years. Stiftung Wissenchaft und Politik (SWP) Research Paper 2. [13] Erdogan ousts Turkey central bank governor days after rate hike | Financial Times [14] 70 percent of Turkey struggling to pay for food, survey finds | Ahval (ahvalnews.com) [15] Turkey's inflation hits 24-year high of 85.5% after rate cuts | Reuters [16] Benjamin, W. (1970). ‘Thesis on the Philosophy of History’, in Arendt, H. (ed.) Illuminations, p.263. Jonathan Cape. by Emily Katzenstein

Emily Katzenstein: You describe your own work in terms of ‘decolonising urban spaces’ through artistic interventions. Can you tell us what that decolonisation means in this context? What projects are you currently working on?

Yolanda Gutiérrez: At the moment, I have two different kinds of projects. One is the Urban Bodies Projects. That’s a project that deals with the colonial past of European cities. I am working with local dancers in each city. The next one will be in Mexico City, and then one, next year, in Kigali. My second project is the Decolonycities Project. That’s a project about dealing with the German colonial past in the city of Hamburg, through the eyes of those who were colonised. I am planning to do five projects in five countries—Togo, Cameroon, Tanzania, Namibia, and Rwanda [countries Germany colonised in the late 19th and early 20th century—eds.] And then I have the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project, which I started when this Bismarck controversy arose. In Hamburg, they are renovating the Bismarck monument for €9 million. It became a big controversy and overlapped with the Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S., and here in Germany. Here in Hamburg, activists started to paint or graffiti all kinds of colonial monuments and symbols of white supremacy. Suddenly, overnight, these monuments had been altered. But you can’t really do that with the Bismarck statue because they’re currently renovating it and it’s surrounded by protective walls. So, we’ve been having a two year long discussion about what should happen with the Bismarck monument. The discussion in Hamburg was driven by a lot of activists, especially people of colour. For me, however, it was important to see what would happen if we brought in the perspectives of artists from former German colonies (Namibia, Cameroon, Togo, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania—eds.) who are living with the consequences of Bismarck’s role in Germany’s colonial past. So I acted as a producer and curator, and I invited artists from the countries that Germany colonised in Africa to stage their own performances in Hamburg, at historical sites that are linked to Germany’s colonial past. The artists who participated were Isack Peter Abeneko[1], Dolph Banza, Vitjitua Ndjiharine, Stone, Moussa Issiaka, Fabian Villasana aka Calavera, Sarah Lasaki, Faizel Browny, Samwel Japhet, and Shabani Mugado. That’s a political statement. When the invited artists put themselves in the spaces that have some significance in Germany’s colonial history, they appropriate those spaces. The artists put on performances that reinterpreted the meaning of the places in which they performed. During the International Summer Festival, when the invited artists from Bismarck-Dekolonial put on their performances, for example, the audience could participate in what I call a decolonising audio-walk: you could see the artists’ performance while simultaneously listening to an audio track that plays the sounds of German troops leaving the Hamburg port, for example—a huge event at the time. So, the audio of German troops leaving from the Hamburg port is juxtaposed with the performance of the artists from Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Cameroon. You are listening to an audio track about the event of German colonial troops leaving from the Hamburg port, and, simultaneously, you see the performances of artists who are descendants of those who were most directly affected by Germany’s colonial policy. We often tend to think of history as something stale, dead—something that belongs in the past, that we don’t care about. In discussions of Germany’s colonial past, that is a reaction that you encounter quite often. People say: That’s in the past and there is nothing that we can do about it. The past cannot be undone. And my reaction is: Yes, the past cannot be undone but we can change the perspective of how we look at history. EK That is something that brings the different contributions of this series together—the sense that the past is, in a sense, contemporaneous, and that the stories that we tell about the past are crucial to our sense of who we are today. Can I come back to the question I asked earlier? What does decolonisation mean when it comes to artistic interventions? How do you conceive of decolonisation in your own work? YG: Yes, my work reflects on the fact that history has been written by the colonisers. For hundreds of years, the colonial gaze has shaped our understanding of the societies that Europeans colonised. For example, during the Spanish conquest of Latin America, Spanish priests often took on the role of historians. Their impressions of the societies they encountered was heavily influenced by the own cultural presuppositions. For example, they had certain notions about the role of women in society, notions about gender roles, etc. That coloured and distorted their view of the societies they tried to describe. In the case of women in Aztec society, for example, they confused expectation and reality, and described what they expected to find—they portrayed Aztec women as unemancipated and occupying a predominantly domestic role, because that’s the way they saw the role of women in Catholic Spain. But now there are new histories of indigenous societies. There was an amazing exhibition in the Linden Museum Stuttgart on Aztecs culture, for example, that reflected very critically on the ways of seeing that have shaped European impressions of Aztec society over generations. That is what I am trying to do in terms of my artistic interventions—to publicise and communicate ‘unwritten’ histories, untold stories, and marginalised historical perspectives. To do that, I work closely with historians. For example, my most recent project is situated in Namibia, which was colonised by Germany in the late 19th and early 20th century. From the beginning, I’ve collaborated with Jan Kawlath, a doctoral student in history at the University of Hamburg. His PhD investigates how the departure of German colonial troops was publicly celebrated to performatively construct images of Germany as a colonial power. And when we visit the historical sites at which we will stage performances, we listen to his writings about events that took place there, and his writing about these places and sites informs our choreography. In that sense, my work is influenced by Gloria Wekker’s work on the cultural archive.[2] Wekker writes so powerfully about the importance of the cultural archive. There’s also a James Baldwin quote that captures it well: “History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals.”[3] EK: In your work, you’ve experimented with different modes of presentation and media to stage decolonising artistic interventions. You already mentioned the ‘decolonising audio-walk’. Can you explain the concept of a decolonising audio walk? YG: Yes, I use the concept of decolonising audio walks in all my projects. The audience has head-phones, and walks to historical sites that have some significance in the colonial past of the city. When you arrive at a site, you see the performance while listening to the audio soundtrack. It is a combination of different types of information, historical facts, interviews with experts, statements by artists, music, etc. etc. Afterwards, you walk to the next site, and so on. It is a way to incorporate a lot of different elements: Dance, audio—it’s an embodied experience for the audience because they walk through the city. Walking through the city allows you to see familiar places with new eyes. I mean, normally, once you’ve lived in a city for a while, you assume you know the place and you’re not going to go on a tour of the city. But then, during the decolonising audio walk, you experience yourself not knowing the city that you assumed you knew, and that allows you to uncover the histories that are normally not talked about. EK On the website of the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project, you raise a question that I found fascinating, and that I wanted to put to you: namely, what kinds of artistic interventions are effective in contributing to decolonising urban spaces? How do you think about the different artistic strategies and interventions one can stage, and about the differences in the impact they have? With regards to the ‘decolonising audio-walk’, is there a tension between this momentary performative intervention and the monuments that embody permanence? Can performances effectively contest the built environment? YG: Performances in urban spaces are a way to reach people easily. By contrast, universities have, for a couple of years, been doing a lot of “Ringvorlesungen” (series of lectures by different speakers), where you have artists and academics talk to each other about decolonisation. I have been following all these discussions, and I think that’s also an interesting approach, but they don’t reach a broad audience. Similarly, in the arts, there are many exhibitions that deal with decolonisation, but they are framed in a very particular way, and it’s for a particular audience; they don’t reach as many people. And what I really love about dance is that it allows me to juxtapose different temporalities and sensory impressions—historical accounts or sounds from the past are juxtaposed with a performance that’s very much in the moment. You can connect the history to which you are listening to what you see. In that sense, it’s a way to demonstrate the contemporaneity of the past. It’s like puzzle pieces coming together. But audio walks, and performances more generally, are ephemeral, and that is my big challenge. You can put on as many performances as you like—for example, during the International Summer Festival 2021 in Hamburg, we put on five performances every day, which was already a lot. But even if you do a hundred performances per day, it doesn’t change the fact that it is ephemeral. So right now, my big question is how we can turn this into something more permanent. Because it’s all about memory, right? It’s about memorials and historical sites that need to be decolonised. And the challenge for me is: How can I, as an artist in the performing arts, leave a print that’s permanent? I am trying to get ‘into memory’ and I am still trying to figure out how far we can go with these performances and audio-walks in historical sites, what their impact is. So that’s my big next challenge. I always say that the fact that the artists who participated in the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project—Isack Peter Abeneko, Dolph Banza, Vitjitua Ndjiharine, Stone, Moussa Issiaka, Fabian Villasana aka Calave, Sarah Lasaki, Faizel Browny, Samwel Japhet, and Shabani Mugado—put on these performances around the Bismarck monument means that the space has been altered. It is no longer the same space, no longer holds the same meaning. The traces they left are ephemeral but they are there, nonetheless. There is a trace. That’s why I want to work on putting up a QR code or something similar. At the moment, my idea is to combine it with a visually appealing sculpture or something else that attracts passers-by, so that they say: “What’s that? I want to know more.” And then they can use the QR code to watch the performance that happened in the space. EK: One of the questions that always structures debates about contested monuments, it seems to me, is how we should think about the relationship between meaning and monuments. As an artist, how do you think about this relationship between monuments and meaning? Can we speak of a ‘hegemonic’ meaning of particular monuments or should we think about a multiplicity of meanings? Should we oppose hegemonic meanings with counter-hegemonic meanings, or prioritise showcasing the diversity and multiplicity of possible interpretations and meanings? What’s your approach to this? YG: In Germany, we haven’t spent enough time reflecting Germany’s colonial past. The Second World War is obviously a horrific part of Germany’s history, and it tends to overshadow everything else, including Germany’s colonial past. But that means that you miss crucial connections, and that people don’t know Germany’s colonial past. For example, that the idea of the concentration camps was first developed during the genocide of the Herero and Nama in Namibia, camps that were built in the beginning of the 20th century. For me, the representation of Bismarck is a symbol of the power that Germany had in the world at that time. In the case of Bismarck, this is dangerous, because it works as a magnet for the right-wing, and we experienced that in a very, very bad way. During the performance of Vitjitua Ndjiharine, a visual artist from Namibia, one person in the audience suddenly went up to her and gave the Hitlergruß. He was facing the Bismarck monument, and stood in front of her, and gave the Hitlergruß. So, trying to deal with this statue and with what it represents is exactly where the power is, for me. I mean, just look at it. The sheer measure of the monument is so imposing. And I think that’s the way that Germans were feeling when they colonised Namibia. If you read the writings of German colonial officials at the time, there is this feeling of supremacy. And that’s difficult to deal with, especially now, when they are polishing the Bismarck monument and literally making it whiter. EK: There have been many proposals as to what should happen with the Bismarck monument. Some have argued that the monument should be removed altogether, others have argued that it should be turned on its head, and yet others propose letting it crumble. I assume letting it crumble is not really an option for safety reasons, but I’ve always liked the symbolism of it. What do you think should happen with the monument? YG: I think if you vanish the Bismarck monument that doesn’t mean that you’ve vanished the meaning of Bismarck in the minds of people; what his figure means for people. And you can’t simply let the monument crumble—the size of the monument means that that is unfeasible. There were issues with the static of the monument, that’s why they’re renovating it. I mean with some monuments, you can let them crumble, no problem, but given the size of the Bismarck monument that’s not feasible. But you know what? I could see it happening in a video, a video that’s then projected unto the Bismarck monument. That’s something that we have experimented with, too. We didn’t pull the statue down but we did what we call ‘video mapping.’ We did it at night, and that’s when I really felt like an activist. I had a generator, and it was midnight, and we had to set everything up. That’s the first time where I had to inform the municipality and said: Hey, I'm going to do this at the Bismarck monument. And they said, OK, that’s fine. You're going to destroy it. Nothing is going to happen. But I mean, you could see the change—suddenly the Bismarck monument became the canvas instead of the symbol it usually represents. Of course, that’s a temporary intervention. But I am also convinced that we need a permanent artistic intervention. I think we need an open space for discussions. For example, I could imagine a garden around the monument, a place where we can keep this dialogue and this discussion going once the renovation is done. I am not a visual artist, obviously, but I was on a podium discussion[4] about decolonising and recontextualising the Bismarck statue with several other artists. There were two very interesting women, Dior Thiam, a visual artist from Berlin, and Joiri Minaya, a Dominican- American artist based in New York. Joiri Minaya has already covered two colonial statues at the port of Hamburg, a statue of Vasco da Gama and a statue of Christopher Columbus, with printed fabrics of her own design[5]—it’s very interesting work. As I said, I am not a visual artist, but I think that a permanent art intervention is necessary. Because what I do is so ephemeral, and I have the sense that we need to reach as broad an audience as possible. EK: The discussions about what to do with the Bismarck monument have been ongoing for the last two years. What impact has the debate had? Do you get the sense that the debate has contributed to a broader political awareness of Bismarck’s role in Germany’s colonial past in Hamburg? Or is this largely a debate amongst a relatively narrow set of actors? YG: Yes, the question about impact. What I got tired of were all these discussions on advisory boards, and advisory committees: People discuss a lot. I am a maker, and I sat at a lot of these discussions and said, yes, we can keep discussing but we also need to do something now. And people had a lot of reasons for why we couldn’t do anything until later. But to me it seemed wrong to wait until the renovations are finished. It seemed like a strange idea to stage an intervention once Bismarck’s shining in all his glory, you know. The discussions are good and all, but they are not enough. They don’t reach enough people; they don’t reach communities. I think it would be fantastic to have something like the project Monument Lab in the United States here in Germany. Monument Lab is combination of different layers of communities—they bring together artists, activists, municipal agencies, cultural institutions, and young people. That’s precisely what we need to do around the Bismarck statue. We need a multilayered participatory process that includes different groups in society. [1] Due to pandemic-related travel restrictions, Isack Peter Abeneko could only participate remotely from Dar es Salaam. [2] Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham, 2016. [3] As cited in I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck (2016; New York: Magnolia Pictures, 2017), Netflix. (1:26:32). [4] Behörde für Kultur und Medien Hamburg, “(Post) colonial Deconstruction: Artistic interventions towards a multilayered monument”, 16.09.2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6215&v=hRFzASv_ea4&feature=emb_logo [5] For images of the covered statues and an explanation about the symbolism of the printed fabrics, see the link above at 1:25-1:30. 4/4/2022 The nationalism in Putin's Russia that scholars could not find but which invaded UkraineRead Now by Taras Kuzio

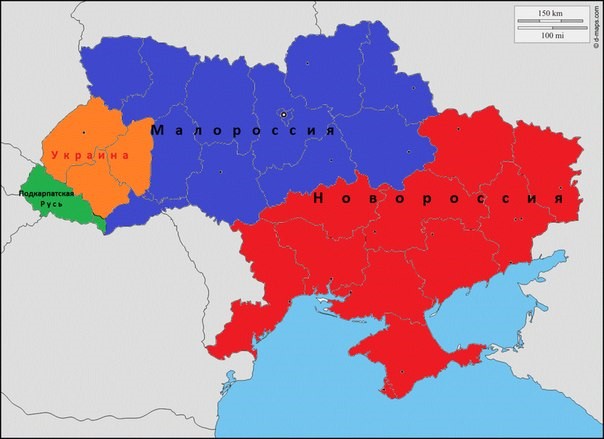

The roots of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are to be found in the elevation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré views, which deny the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[1] The Soviet Union recognised Ukrainians as a people separate but close to Russians. Russian imperial nationalists hold a Jekyll-and-Hyde view of Ukraine. While denigrating Ukraine in a colonial manner that would make even Soviet-era Communist Party leaders blush, Russian leaders at the same time claim to hold warm feelings towards Ukrainians, whom they see as the closest people to them. In this light, ‘bad’ Ukrainians are nationalists and neo-Nazis who want their country to be part of Europe; ‘good’ Ukrainians are obedient Little Russians who know their place in the east Slavic hierarchy and want to align themselves with Mother Russia. In other words, ‘good’ Ukrainians are those who wish their country to emulate Belarus. In practice, during the invasion, cities such as Kharkiv and Mariupol that have resisted the Russian incursion have been pulverised irrespective of the fact they are majority Russian-speaking. In turn, the fact of this resistance means to Russia’s leaders that these cities are inhabited by ‘Nazis’, not Little Russians who would have greeted Russian troops—and who should therefore be destroyed. Without an understanding of the deepening influence of Tsarist imperial nationalism in Russia since 2012, and especially following Crimea’s annexation in 2014, scholars will be unable to grasp or explain why Putin has been so obsessed with returning Ukraine to the Russian World—a concept created as long ago as 2007 as a body to unite the three eastern Slavs, which underpinned his invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Putin’s invasion did not come out of nowhere, but had been nurtured, discussed, and raised by Putin and Russian officials since the mid-2000s in derogatory dismissals of Ukrainians, and in territorial claims advanced against Ukraine. Unfortunately, few scholars took these at face value until summer 2021, when Putin published a long 6,000-word article[2] detailing his thesis about Russians and Ukrainians constituting one people with a single language, culture, and common history.[3] Ukrainians were a ‘brotherly nation’ who were ‘part of the Russian people.’ ‘Reunification’ would inevitably take place, Putin told the Valdai Club in 2017.[4] The overwhelming majority of scholarly books and journals have dismissed, ignored, or downplayed Russian nationalism as a temporary phenomenon.[5] Richard Sakwa claimed Putin was not dependent upon Russian nationalism, ‘and it is debatable whether the word is even applicable to him.’[6] Other scholars described it as a temporary phenomenon that had disappeared by 2015–16.[7] A major book on Russian nationalism published after the 2014 crisis included nothing on the incorporation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré discourse that dismissed the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[8] Russia’s invasion of Ukraine backed by Russian nationalist rhetoric has led to many Western academics suggesting that the Russian forces have ended up—or will end up—with egg on their faces. Why they felt the need to take this angle has varied, ranging from elaborate political science theories popular in North America about the nature of the Russian regime to the traditional Russophilia found among a significant number of Euro-American scholars writing about Russia.[9] As Petro Kuzyk pointed out, in writing extensively about Ukrainian regionalism, scholars have tended to exaggerate intra-Ukrainian regional divisions. [10] This has clearly been seen during the invasion, when Russia has found no support among Russian-speakers in cities such as Kharkiv, Mariupol, Odesa, and elsewhere. Furthermore, the prevailing consensus prior to the invasion among scholars and think tankers was eerily similar to that in Moscow; namely, that Ukraine would be quickly occupied, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy would flee, and Kyiv would be captured by Russian troops. That this did not happen again shows a a serious scholarly miscalculation about the strength of Ukrainian identity, and an overestimation of the strength of Russian military power.[11] Nationalism in Putin’s Russia has integrated Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms into an eclectic ruling ideology that drives the invasion. Putin, traditionally viewed as nostalgic for the Soviet Union, has also exhibited some pronounced anti-Soviet tendencies, above all in criticising Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin for creating a federal union of republics that included ‘Russian lands’ in the south-east, and artificially creating a ‘fake’ Ukrainian people. Putin’s invasion goal of ‘denazification’[12] aimed to correct this mistake by destroying the ‘anti-Russia’ nurtured by the West.[13] Both scholars and Russian leaders have been baffled as to how to understand and explain the tenacity of Ukrainian identity that has fought the Russian army to a standstill, and is now in the position of launching counterattacks. What is particularly difficult for Russian political leaders and media journalists to explain is how a people that supposedly does not exist (Ukrainians) could greet the ‘special military operation’ (Putin’s dystopian term for the invasion of Ukraine) not with bouquets of flowers but met it with armed resistance. Instrumentalism: Russian Nationalism as a Temporary Phenomenon Sakwa[14] writes that ‘the genie of Russian nationalism was firmly back in the bottle’ by 2016. Pal Kolstø and Marlene Laruelle, along similar lines, write that the nationalist rhetoric of 2014 was novel and subsequently declined.[15] Meanwhile, Henry Hale[16] also believes Putin was only a nationalist in 2014, not prior to the annexation of the Crimea or since 2015. Laruelle[17] concurs, writing that by 2016, Putin’s regime had ‘circled back to a more classic and pragmatic conservative vision’. Laruelle describes Putin’s regime as nationalistic only in the period 2013–16, arguing that ‘since then [it] has been curtailing any type of ideological inflation and has adopted a low profile, focusing on much more pragmatic and Realpolitik agendas at home and abroad.’[18] Paul Chaisty and Stephen Whitefield write, ‘Putin is not a natural nationalist’ and ‘[w]e do not see the man and the regime as defined by principled ideological nationalism.’[19] Sakwa[20] is among the foremost authors who deny that Putin is a nationalist, describing him as not an ideologue because he remains rational and pragmatic—which sharply contrasts with an invasion that most commentators view as irrational. Allegedly, moreover, there has been a ‘crisis’ in Russian nationalism.[21] Other scholars, meanwhile, believed that Putin ‘lost’ nationalist support.[22] In reality, the opposite took place. Russian imperial nationalism deepened, penetrated even further into Russian society and became dominant in Putin’s regime during the eight years between the invasions of Crimea and Ukraine. Russian imperial nationalist denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians became entrenched and have driven the invasion of Ukraine. Patriots and Conservatives - Not Nationalists Scholars described Russian nationalists as ‘patriots’ and western-style ‘conservatives.’ In the same year that the constitution was changed to allow Putin to remain president until 2036, Laruelle writes ‘the Putin regime still embodies a moderate centrist conservatism.’[23] Petro, Sakwa, and Robinson analogously describe a ‘conservative turn’ in Russian foreign policy.[24] If contemporary British conservatives annexed part of Ireland and denied the existence of the Irish people, “conservatism” would no longer fully capture the ideology they represented. By the same token, the Putin regime’s annexation of Crimea and denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians has sharply steered Russian conservatism towards the conceptual centrality of imperial nationalism. In their analyses, Sakwa and Anna Matveeva could only identify ‘militarised patriotism’ or elites divided into ‘westerners’ and ‘patriots.’[25] Following his 2012 re-election, Sakwa writes that Putin only spoke of ‘Russian identity discourse’ and Putin’s ‘conservative values’ which he believes should be not confused with a Russian nationalist agenda.[26] Sakwa has generally avoided using the term ‘nationalist’ when discussing Russian politicians. This created problems in explaining why a ‘non-nationalist’ Putin might choose to support a wide range of far-right and a smaller number of extreme left political movements in Europe and the US, ranging from national-conservatives, populist-nationalists, irredentist imperialists to neo-Nazis in Europe. Sakwa[27] attempts to circumvent this conundrum by relying on a portfolio of euphemistic alternatives, describing these far-right and extreme left movements as ‘anti-systemic forces,’ ‘radical left,’ ‘movements of the far right,’ ‘European populists,’ ‘traditional sovereigntists, peaceniks, anti-imperialists, critics of globalisation,’ ‘populists of left and right,’ and ‘values coalition.’ Putin’s Imperial Nationalist Obsession with Ukraine The Soviet regime recognised a separate Ukrainian people, albeit one that always retained close ties to Russians. The Ukrainian SSR was a ‘sovereign’ republic within the Soviet Union. In 1945, Joseph Stalin negotiated three seats at the UN for the USSR (representing the Russian SFSR), Ukrainian SSR, and Belarusian SSR. In the USSR, there was a Ukrainian lobby in Moscow, while this has been wholly absent under Putin.[28] Soviet nationality policy defined Ukrainians and Russians as related, but nevertheless separate peoples; this was no longer the case in Putin’s Russia. In the USSR, Ukraine, and the Ukrainian language ‘always had robust defenders at the very top. Under Putin, however, the idea of Ukrainian national statehood was discouraged.’[29] Although the USSR promoted Russification, it nevertheless recognised the existence of the Ukrainian language. For a decade prior to the invasion, the Ukrainian language was disparaged by the Russian media and political leaders as a dialect that was artificially made a language in the Soviet Union.[30] Russian nationalist myths and stereotypes underpinning the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had been raised, discussed, and threatened for over a decade prior to the ‘special military operation’. When Putin returned as president in 2012, he portrayed himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian [i.e., eastern Slavic] lands.’ Ukraine’s return to the Russian World, alongside Crimea and Belarus, was Putin’s unfinished business that he needed to accomplish before entering Russia’s history books. Ukraine, as a ‘Russian land’, should fall within the Russian World and remain closely aligned to Russia. Ukrainians, on this account, had no right to decide their own future. Russia sought to accomplish Ukraine’s return to the Russian World through the two Minsk peace agreements signed in 2014–15. Ukrainian leaders resisted Russian pressure to implement the agreements because they would have created a weak central government and federalised state where Russia would have inordinate influence through its proxy Donetsk Peoples Republic and Luhansk Peoples Republic. The failure of Russia’s diplomatic and military pressure led to a change in tactics in October 2021. Early that month, former President Dmitri Medvedev, now deputy head of Russia’s Security Council, penned a vitriolic attack on Ukrainian identity as well as an anti-Semitic attack on Jewish-Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ruling out further negotiations with Kyiv.[31] Medvedev claimed Ukrainian leaders were US puppets, and that therefore the Kremlin needed to negotiate directly with their alleged ‘puppet master’—Washington. Meanwhile, Russia would ‘wait for the emergence of a sane leadership in Ukraine,’ ‘who aims not at a total confrontation with Russia on the brink of war…but at building equal and mutually beneficial relations with Russia.’[32] Medvedev was revealing that Russia’s goal in any future military operation would be regime change, replacing an ‘anti-Russia’ leadership with a pro-Kremlin leader.[33] In early November 2021, Russia’s foreign policy machine mobilised and made stridently false accusations about threats from Ukraine and its ‘Western puppet masters.’ Russia began building up its military forces on the Ukrainian border and in Belarus. In December 2021, Russia issued two ultimatums to the West, demanding a re-working of European security architecture. The consensus within Euro-American commentary on the invasion has been that this crisis was completely artificial. NATO was not about to offer Ukraine membership, even though Ukraine had held periodic military exercises with NATO members for nearly three decades, while the US and NATO at no point planned to install offensive missiles in Ukraine. The real cause of the crisis was the failure of the Minsk peace process to achieve Ukraine’s capitulation to Russian demands that would have placed Ukraine within the Russian sphere of influence. After being elected president in April 2019, Zelenskyy had sought a compromise with Putin, but he had come round to understanding that this was not on offer. The failure of the Minsk peace process meant Ukraine’s submission would now be undertaken, in Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s words, by ‘military-technical means’—that is, the ‘special military operation’ that began on 24 February 2022. Russian Imperial and White Émigré Nationalism Captures Putin’s Russia Downplaying, marginalising, and ignoring Russian nationalism led to the ignoring of Russian nationalism’s incorporation of Tsarist and White Russian émigré denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Marginal nationalism in the 1990s became mainstream nationalism in Russia in the 2000s under Putin when the ‘emergence of a virulent nationalist opposition movement took the mainstream hostage.’[34] The 1993 coup d’état against President Boris Yeltsin was led by a ‘red-brown’ coalition of pro-Soviet and far-right nationalists and fascists. The failure of the coup d’état and the electoral defeat of the Communist Party leader Gennadiy Zyuganov in the 1996 elections condemned these groups to the margins of Russian political life. At the same time, from the mid 1990s, the Yeltsin presidency moved away from a liberal to a nationalist foreign and security approach within Eurasia and towards the West. This evolution was discernible in the support given to a Russian-Belarusian union during the 1996 elections and in the appointment of Yevgeny Primakov as foreign minister. Therefore, the capture of Russia by the Soviet siloviki began with the Chairman of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Primakov, four years before the chairman of the Federal Security Service (FSB), Putin, was elected president. Under Primakov, Russia moved from defining itself as part of the ‘common European home’ to the country at the centre of Eurasia. Under Putin, the marginalised ‘red-brown’ coalition gradually increased its influence and broadened to include ‘whites’ (i.e., nostalgic supporters of the Tsarist Empire). Prominent among the ideologists of the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition was the fascist and Ukrainophobe Alexander Dugin, who has nurtured national-Bolshevik and Eurasianist political projects.[35] In the 2014 crisis, Dugin, then a professor at Moscow State University, stated: ‘We should clean up Ukraine from the idiots,’ and ‘The genocide of these cretins is due and inevitable… I can’t believe these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are wonderful Slavonic people. And this is a race of bastards that emerged from the sewer manholes.’[36] During the 2000s the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition came to prominence and Putin increasingly identified with its denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Tsarist imperial nationalism was integrated with Soviet nostalgia, Soviet traditions and symbols and historical myths, such as the Great Patriotic War. Since the mid 2000s, only five years into his rule, Putin spearheaded the rehabilitation of the White Russian émigré movement and reburial of its military officers, writers, and philosophers in Russia. These reburials took place at the same time as the formation of the Russian World Foundation (April 2007) and unification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the émigré Russian Orthodox Church (May 2007). These developments supercharged nationalism in Putin’s Russia, reinforced the Tsarist element in the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition and fuelled the growing disdain of, and antipathy towards Ukraine and Ukrainians that was given state support in the media throughout the two decades before the invasion.[37] Putin personally paid for the re-burial of White Russian émigré nationalists and fascists Ivan Ilyin, Ivan Shmelev, and General Anton Deniken, who called Ukraine ‘Little Russia’ and denied the existence of a separate Ukrainian nation. These chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians were typical of White Russian émigrés. Serhy Plokhy[38] writes, ‘Russia was taking back its long-lost children and reconnecting with their ideas.’ Little wonder, one hundred descendants of White Russian émigré aristocrats living in Western Europe signed an open letter of support for Russia during the 2014 crisis. Putin was ‘particularly impressed’ with Ilyin, whom he first cited in an address to the Russian State Duma as long ago as 2006. Putin recommended Ilyin to be read by his governors, senior adviser Vladislav Surkov, and Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev. The intention was to use Ilyin’s publications in the Russian state programme to inculcate ‘patriotism’ and ‘conservative values’ in Russian children. Ilyin was integrated into Putin’s ideology during his re-election campaign in 2012 and influenced Putin’s re-thinking of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands;’ that is, integrating Belarus and Ukraine into the Russian World, and specifically his belief that the three eastern Slavs constituted a pan-Russian nation.[39] Laruelle has downplayed the importance of Ilyin’s ideology, writing that he did not always propagate fascism, and that Putin only quoted him five times.[40] Yet Putin has not only cited Ilyin, but also asked Russian journalists whether they had read Deniken’s diaries, especially the parts where ‘Deniken discusses Great and Little Russia, Ukraine.’[41] Deniken wrote in his diaries, ‘No Russian, reactionary or democrat, republican or authoritarian, will ever allow Ukraine to be torn away.’[42] In turn, Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré denials of Ukraine and Ukrainians were amplified in the Russian media and in its information warfare for over a decade prior to the invasion. Ukraine and Ukrainians were mocked in the Russian media in a manner ‘typical in coloniser-colonised relationships.’[43] Russia and Russians were cast as superior, modern, and advanced, while Ukraine and Ukrainians were portrayed as backward, uneducated, ‘or at least unsophisticated, lazy, unreliable, cunning, and prone to thievery.’ As a result of nearly two decades of Russian officials and media denigrating Ukraine and Ukrainians these Russian attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians ‘are widely shared across the Russian elite and populace.’[44] This is confirmed by a March 2022 survey conducted by Russia’s last remaining polling organisation, the Levada Centre, which found that an astronomical 81% of Russians supporting Russian military actions in Ukraine. Among these supporters, 43% believe the ‘special military operation’ was undertaken to protect Russophones, 43% to protect civilians in Russian-occupied Donbas, 25% to halt an attack on Russia, and 21% to remove ‘nationalists’ and ‘restore order.’[45] Russian Imperial Nationalist Denigration and Denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians Russian imperial nationalist views of Ukraine began to reappear as far back as the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections, when Russian political technologists worked for pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych’s election campaign, producing election posters designed to scare Russian speakers in south-eastern Ukraine about the prospect of an electoral victory by ‘fascist’ and ‘nationalist’ Viktor Yushchenko. This was when Russia revived Soviet ideological propaganda attacks against Ukrainian nationalists as ‘Nazi collaborators.’ Putin’s cult of the Great Patriotic War has been intricately linked to the promotion of Russia as the country that defeated Nazism in World War II (this is not true as all the Soviet nations contributed to the defeat) and which today is fighting contemporary Nazis in Ukraine, Poland, the three Baltic states, and beyond. Ukraine’s four de-communisation laws adopted in 2015 were despised in Moscow for many reasons. The most pertinent to this discussion was one law that equated Nazi and Soviet crimes against humanity (which contradicted Putin’s cult of Stalin[46]) and another law that moved the terminology of Ukraine’s wartime commemorations from the 1941–45 ‘Great Patriotic War’ to ‘World War II’ of 1939–45.[47] One of the 2004 election posters, reproduced below, imagines Ukraine in typical Russian imperial nationalist discourse as divided into three parts, with west Ukraine as ‘First Class’ (that is, the top of the pack), central Ukraine as ‘Second Class’ and south-eastern Ukraine as ‘Third Class’ (showing Russian speakers living in this region to be at the bottom of the hierarchy). Poster Prepared by Russian Political Technologists for Viktor Yanukovych’s 2004 Election Campaign Text:Yes! This is how THEIR Ukraine looks. Ukrainians, open your eyes! The map of Ukraine in the above 2004 election poster is remarkably similar to the traditional Russian nationalist image of Ukraine reproduced below: Map of Russian Imperial Nationalist Image of Ukraine Note: From right to left: ‘New Russia’ (south-eastern Ukraine in red), ‘Little Russia’ (central Ukraine in blue), ‘Ukraine’ (Galicia in orange), ‘Sub-Carpathian Rus’ (green).

Putin’s Growing Obsession with Ukraine Ignored by Scholars Imperial nationalism came to dominate Russia’s authoritarian political system, including the ruling United Russia Party. Putin’s political system copied that of the late USSR, which in turn had copied East European communist regimes that had created state-controlled opposition parties to provide a fake resemblance of a multi-party system. In 1990, the USSR gave birth to the Liberal Democratic Party of the Soviet Union, becoming in 1992 the Liberal Democratic Party of the Russian Federation (LDPRF). Led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the LDPRF repeatedly made loud bellicose statements about Ukraine and the West. The LDPRF’s goal has always been to attract nationalists who would have otherwise voted for far-right political parties not controlled by the state. In the 1993 elections following the failed coup d’état, the LDPRF received 22.9% - more than the liberal Russia’s Choice Party (15%) and the Communist Party (KPRF). Under Putin, these state-sponsored political projects expanded to the extreme left through the national-Bolshevik Motherland Party, whose programme was written by Dugin, and the Just Russia Party, which was active in Russian-occupied Donbas. Putin’s authoritarian regime needs internal fifth columnists and external enemies. Domestically, these include opposition leaders such as Alexei Navalny, and externally ‘anti-Russia’ Ukraine and the West. Changes to the Russian constitution in summer 2020 extended the ability of Putin to remain president for fifteen years, but in effect made him president for life. Political repression and the closure of independent media increased after these changes, as seen in the attempted poisoning of Navalny, and grew following the invasion of Ukraine. In 2017, The Economist said it was wrong to describe Russia as totalitarian;[48] five years later The Economist believed Russia had become a totalitarian state.[49] A similar evolution has developed over whether Putin’s Russia could be called fascist. In 2016, Alexander J. Motyl’s article[50] declaring Russia to be a fascist state met with a fairly tepid reception. and widespread scholarly criticism.[51] Laruelle devoted an entire book to decrying Russia as not being a fascist state, which was ironically published a few weeks after Russia’s invasion.[52] By the time of the invasion, all the ten characteristics Motyl had defined as constituting a fully authoritarian and fascist political system in Russia were in place: