by Richard Shorten

Author's Note: The expectation to communicate from personal experience is a crucial driver of modern politics. A recent book I have written, The Ideology of Political Reactionaries, shows how reactionaries have mastered, but subverted, this expectation. Therefore, progressives need to do better. Voice has ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘what’ aspects that need exploring both more explicitly and more creatively. My short discussion distils voice into six foremost elements: argument style, emotional tone, metaphor, prioritising, humour, and personality. Together, these can be wrested into ways for exercising voice in greater (and more meaningful) equality, co-operation, and solidarity: respectively, to reflect, to feel, to connect, to weigh, to confide, and to become energised.

* * * Academics used to like to define politics as a matter of ‘who gets what, when, and how’. Lately, it has become a matter of who can say what. And how, and when. ‘Culture wars’, ‘wokeism’, and ‘cancel culture’ are all names for things that make people more aware that there is nothing irrelevant or nondescript about voice. Nor is there anything innocent about it. Voice is what people—not just politicians—use to make them real for others. And, it might be added, for themselves. Hence the two parallel expressions, to ‘find one’s voice’, and to ‘give voice’ to others (via an originating act of the giver’s own voice, that is). But ever since the global financial crisis of 2008, progressives have surrendered this ground, and done so meekly. So, in relation to predictable but also unpredictable public issues, reactionaries have grown mutating and enlarging constituencies of support, many proving storm-like and short-lived, but some showing worrying signs of being longer-lasting: enthusiasts for Trumpism post-Trump; immigration and climate change deniers morphing into Covid vaccine sceptics; Zemmouristes, as well as Lepenistes, outlasting the gilets jaunes in France. The Ideology of Political Reactionaries tries to distill the reactionary voice, to break it down into its ingredients and make it plain. There is a baseline unity to reactionary ideology, notwithstanding its varying content across particular iterations: all reactionary ideology (from Euroscepticism in its mild form to neofascism at its strongest) participates in the prominent sounding of a rhetorical core comprising indignation, decadence, and conspiracy. Aside from the getting the historical and contemporary records straight (reactionism has a shady border with conservatism; reactionary ‘nostalgia’ is chimerical because the message is always more embittered than melancholic; the explanation by post-truth ignores the persistent fetishisation of facts), the study is intended as a nudge towards building a more desirable rhetorical public culture. How do language, tone, and style connect reactionaries in and across Europe and America’s past and present? What starts to look enduring at least once the fascination with the apparent novelty of digital media is scaled back just a bit? And what do things look like when we lay out beside one another quite diverse packages of words and gestures for comparison and inspection? Such examination ought to be revealing, even if the lessons for progressives will, in the first instance, have to emerge by default inversion. And equally, it will show that ‘who can say what, when, and how’ is not simply a topical problem of politics and culture. It is actually quite an old one. Reactionaries do not reject the in-vogue imperative to communicate from personal experience. Publicly, and on the surface, they might demean it. But, in truth, they subvert it. Reactionaries know that the authority to speak is closely bound up with personal involvement in what is spoken (i.e., having skin in the game); timing (e.g., taking care not to speak before others have been heard); and manner. They know this, even if their ‘knowing’ should really be understood more as the product of habit and inclination than of implausibly all-seeing calculative intent. On a tentative estimate, they know, and subvert, voice in at least six ways. Argument style Perhaps the first rule of voice in politics is that the task is to make space. Reactionaries recognise this, and one thing they are always sure to do is to make space to reflect. They upend progressive calls to reflection. They do their best, in written and spoken word, to steer any thinking about politics whatsoever through the prior filter of a story about the unstoppability of decline. Such stories—which technically are ‘narratives’ (in the meaningful way, not in the way dulled by generalised over-use to refer to any sense-making exercise whatsoever)—vary in content. But invariably, they are all-absorbing. Progressives ought to do nothing so grandiose as to craft sweeping counter-narratives. But they must find ways to open up, and in due course expand, alternative spaces for reflection, spaces that that are focused around objects of concern that are simultaneously human and humane. Human, because they will resist being formed around immovable abstractions (which is the historical case of adaptable reactionary fixation around ‘revolution’, ‘defeat’, ‘feminism’, etc.).[1]). Humane, because space-shaped reflection would be unapologetically ethical, impatient with the conjuring of ‘liberalism’ into the enemy, or with the celebration of conflict for opposition’s sake. Emotional tone Not only as an afterthought, making the space to feel must take up an important place next to making the space to reflect. The objects of concern created by the reactionary voice are self-referencing: reactionaries pity themselves and those like them. This is the glue that binds. It is also the basis for feelings that are externally directed towards what are made into targets, specifically, targets of anger. The sense conveyed that this anger is not something that has been heard to date—that it has been suppressed, unacknowledged, allowed to fester—is how a circle is squared with the timing rule: licence for reactionaries to speak is to have successfully created the impression that those people being spoken ‘for’ have long been unheard, and remain still unheard. But used creatively in collective life, emotional tone of voice makes people attentive—thereafter receptive—to the vulnerability of others, who, moreover, are others in their fullest diversity. Hence moral philosophers talk of the ‘circle’ of concern. The task, by modulating tone of voice, is to expand that circle, and to do so without de-intensifying attachments in the process. Uplift, good will, faith in others: the promotion of all these things is often made to seem trite, a pathology of the extension of psychotherapeutic language into politics. But that itself is a function of the snare of cynicism in contemporary rhetorical public culture; in turn, a complex cause and effect of reactionary ‘edginess’ in its particular alt-right incarnation. Feelings liable to be dismissed as trite in any case do not exhaust the range of emotions far more likely to be timely to any moment than unspent self-pity: sorrow at wasted lives and livelihoods; outrage, not festering anger, at perpetration, complicity, or indifference. Metaphor Making the space to connect is another capability of voice. Metaphor connects the person to other people; it also helps that person to connect things to things. Reactionaries cement fellow-feeling with others who are not really like them, not in a way that couldn’t be challenged by more plausible connections; connections far more immanent in the the structures of social and political experience. Reactionaries do so by act of making the particular universal, or the part into whole (which more technically belongs to the branch of metaphor that is metonymy). In this way, dethroned monarchs, culturally-mocked millionaires, and failed artists can all be made mirrors to the hardships of the truly vulnerable, because the suffering in each of these scenarios—and the suffering of individuals—becomes representative: not statistically or descriptively representative, but symbolically representative. (Victimhood becomes the state of being belittled in whichever way makes meaning reflect back in this conveniently dangled mirror.) How reactionaries connect things-to-things is by metaphors that are dominantly naturalist and hyper-masculinist. Metaphors from ecology or biology, in particular, dramatise what thereby becomes deep-rooted, health-threatening decline, in idioms that can extend to the frankly carnal. An under-appreciated aspect of the ideology of Eric Zemmour, for example, is the loss of male virility (which, inside his 2014 book The French Suicide, is far more a trope than the national ‘suicide’ of the title). Decoding reactionaries by metaphor is one step towards disarming them, but the next task is to turn the metaphors inside out, to craft them to more humane purpose and effect. One way of doing this is by explicitly reclaiming bodily metaphor, for it is the body which provides human vulnerability with its shared site. Another way of doing so is to take the structure of analogical reasoning (which works on the idea that because you accept something similar already, you will accept something else proposed), to wrest it away from its dominant reactionary or conservative uses (in idealisation of the status quo or status quo ante), and to place it into progressive use. Co-opted analogical reasoning would work on the idea that what has most meaningful prior acceptance is not overtly bound to parochial culture: people’s most pre-existing commitment of all is to be their best selves. Prioritising Prioritising by voice is identifying issues and embracing the task to weigh. Reactionaries weigh issues often with outward portent, but, ultimately, trivially. They do so habitually by lists, or by acts of either linguistic or literary brutalism. List arrangements of projected wrongs and grievances allow for the heaping up of externally-directed criticism and censure, fabricating the illusion of rising gravity. By imagined actions (or sometimes by sheer temerity of existing) migrants, ethnic Others or cartoonised social justice warriors can made to bask in the negative spotlight, and on that basis be made to shoulder blame for whole unlikely catalogues of sins. Brutalism in words and sentences is the creation of heightened urgency by graceless transition, jolting an audience into attention; and, by unfortunate correlation, repeated jolting has the simultaneous effect of deadening human sensitivity. Lists plus brutalism may not exhaust reactionary techniques for deleteriously amplifying concerns, but above all this is a faux seriousness, a seriousness of the shrill or the pompous. What it doesn’t need is more of the same in reply. In the political act of prioritising—which is necessary not primarily because decision-making capacity is finite, but rather because the political imagination is drawn towards specific things and/ or specific persons—the practice of hierarchical ordering is hard to dispel in its entirety, but comes with downsides that may nevertheless be counter-acted. To be sure, listing bona fide wrongs has a dignity that listing imagined injustices does not. However, within contemporary culture, bona fide wrongs have frozen into competitive victimhoods: injury by racism versus class; by sex-based versus gender-based oppression; by historical fascism versus historical colonialism. And one way of chipping away at this (by wakening metaphor again) is to try to introduce alternative spatial orientations into public language: suffering that is neither ‘above’ and ‘below’, nor ‘before’ and ‘after’. Are there ways of juxtaposing experiences that are more consensual than conflictual? Ways that will not cancel out sympathy generated, but render sympathy liable to be reproduced in many directions, even perhaps in ever more fine-grained complexions? Humour Humour in voice is, or can be, a way by which to commune: to confide, to reassure. In reactionary voice, it is anything but. Psychologists of humour talk of humour style, and reactionary styles of humour tend strongly towards the maladaptive, i.e., aggressive. Rarely do reactionaries participate in the affiliative style of humour which (to play upon the original religious meaning of ‘to commune’ from communion) is capable of firming up human relationships by exchange of thoughts and feelings. Reactionary humour is the humour of put-downs and jibes at out-groups, destructive of bridge-building between people. Fairly recently, in the United States, Sarah Palin—the vice-presidential contender and under-emphasised forerunner of Donald Trump—developed a political style that gave a lot of time to unkind mimicry. In British politics, Nigel Farage experimented with a humour style that drifted into bullying, offset only partially by the kind of jocularity that gestured beyond the aggressive by virtue of being self-effacing and buffoonish: the notional punches-upwards could be unceremoniously dumped for punches-sidewards, soon becoming punches-downwards (recall the public humiliation of Herman van Rompuy in the European Parliament). In the terms of theories canvassed across the history of thought, then conspicuously often—to the point of being a rule—the humour of reactionaries matches the comedy identified by Hobbes, operating by ridicule and superiority; not the tension-release by laughter observed by Freud, and still less the comedy that arises out of incongruity (between expectation and occurrence, between unconventionally paired ideas). Alternatively, non-Hobbesian humour is only at a very crude level urbane and elitish, or metropolitan because cosmopolitan. And it is very far from being exclusive since (in a last piece of humour taxonomy) it is open to expression in whole range of types: from the dark, dry and droll, through to the satirical, slapstick, and screwball. In France, currently, Eric Zemmour does possess a more stylish line in witticism. His niche in The French Suicide is to observe paradox, presented as incongruity between the intentions of both leftists and liberals and the effects of their policies. But his paradoxes are not really paradoxes: they are wilfully dark contrasts (such as that gay people were freer when encouraged to be discreet about their sexuality, or that straight women could be less guilty about sex when there existed rigid social norms to police their access to it). And in the process, there may be an instructive lesson about the need to unpick nuances in the uses of dark humour: Zemmour’s are wilful contrasts not only in the sense of being false, but also in the sense of being, ultimately, victim- (and not victimiser-)mocking. As such, shorn of the more appealing victim-empathising quality of ‘gallows humour’, the humour in his book is reduced to word-play. Which is clever, but not funny. Personality Voice also offers, lastly, the chance to inspire, in the possibility of positive response to the comportment of others. This last thing reactionaries know is that expressing viewpoint is simultaneously opportunity to display the virtues one carries. In reactionary practice, those are shallow virtues at best, and misguided inspiration. Charisma is more often bombast. Authenticity is double-edged, and in any event is contradictory to charisma. Bravery is martyring. Bragging should not be mistaken for much inspirational at all. And publicising insider knowledge—Trump’s business prowess, Farage’s Brussels days, Joseph McCarthy’s dogged curiosity—is (as well as in tension with flagging outsider credentials to denigrate ‘expertise’) the accomplice of community-destroying conspiracy claims that are reliably present. This is not collegiality; not integrity or honesty; not gentleness and generosity; not constancy or meaningful self-knowledge. There is, to appreciate, an intrinsic difficulty in trying to craft the progressive articulation of personality in voice: the infra-person location of vocal chords, or the hand-gripped wielding of the pen, point to the hazard of carrying over-exaltation of individual action into the securing of new collective space, pushing against the collective exchange of perspectives. So, minimally, one part of comportment must tasked with trying to find a balance with modesty, as well as with trying to achieve a particular split: between twin tasks of showing one’s skin in the game and bringing others into it. It is here, finally, that some existing conceptualisations of voice on the progressive side of politics are suspect. To be sure, from out of the conventions of academic political science, these present accounts improve vastly on the most established, most frequently-cited account: a 1970 text which makes voice into an alternative to ‘exit’, into a grossly individualised phenomenon, and, fundamentally, a matter of interest, not principle (in effect: ‘I’m not very happy about this, so I’m saying so’). But the dominant, progressive accounts are suspect nevertheless, and suspect, specifically, in respect to the conceptualisation of movement. Rightly, they contest the uniform flatness—the stuckness—of reactionary representations of ‘vox populi’: instead, at their best, they stress the importances of co-creating the meaning of experience, and fashioning demands on that basis. And rightly (albeit from a distinct angle), they stress the ‘situatedness’ of voice. Yet working against these stresses, they tend to portray the who-ness of voice as if the issue were pre-settled. Plus, on the issue of what people ought to do with voice once they get there, they are hesitant, such that they under-estimate the complexities of ‘when’ and ‘how’. Enabling voice, whether for progressives of either a moderate or more radical kind, presently tends to be understood as a single movement: either to or from a single location. Just the direction is reversed. For moderates, the movement is dominantly ‘toward’—in which voice is something graciously presented to somebody, as though receiving a gift-giving guest (‘there you go, here is voice, now use it’). For radicals, the movement is ‘away from’—by beseechment to join something at some distance from a starting point (‘“come to voice” with us’)—and with just a hint that before being exercised, the new joiners’ voices will need to pass through a final stage of screening by older occupants. The future situational pressures on voice cannot, by nature, be foretold. But if the inverted lessons from reactionary practice are instructive, then the desiderata for better voice will—centrally—comprise maximal inclusion, minimal coercion, or pluralism in balance with empathy. From this starting set of features: to reflect, to feel, to connect, to weigh, to confide, be energised. To genuinely co-create. To use voice so that it sounds—then echoes—in a multitude of directions. Above all, to use voice to make space so that others might find space in it of their own. [1] Note that this immovability by abstraction can even be a risk for contemporary progressives, who, following a very timely call for an appreciation of what is ordinary (cf. Marc Stears, Out of the Ordinary: How Everyday Life Inspired a Nation and How It Can Again [Belknap Press, 2021]), can often be drawn towards abstractifying the value of the ‘everyday’. 4/4/2022 The nationalism in Putin's Russia that scholars could not find but which invaded UkraineRead Now by Taras Kuzio

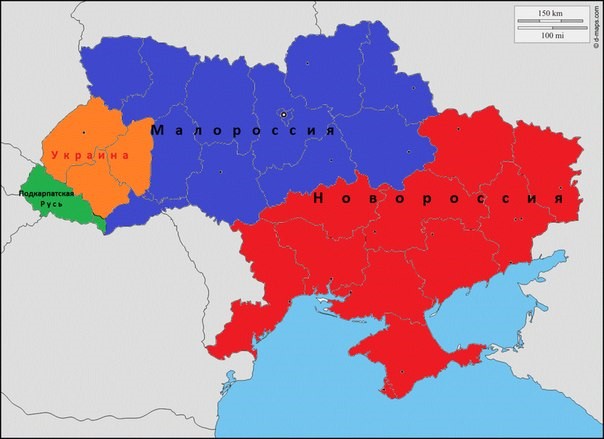

The roots of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are to be found in the elevation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré views, which deny the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[1] The Soviet Union recognised Ukrainians as a people separate but close to Russians. Russian imperial nationalists hold a Jekyll-and-Hyde view of Ukraine. While denigrating Ukraine in a colonial manner that would make even Soviet-era Communist Party leaders blush, Russian leaders at the same time claim to hold warm feelings towards Ukrainians, whom they see as the closest people to them. In this light, ‘bad’ Ukrainians are nationalists and neo-Nazis who want their country to be part of Europe; ‘good’ Ukrainians are obedient Little Russians who know their place in the east Slavic hierarchy and want to align themselves with Mother Russia. In other words, ‘good’ Ukrainians are those who wish their country to emulate Belarus. In practice, during the invasion, cities such as Kharkiv and Mariupol that have resisted the Russian incursion have been pulverised irrespective of the fact they are majority Russian-speaking. In turn, the fact of this resistance means to Russia’s leaders that these cities are inhabited by ‘Nazis’, not Little Russians who would have greeted Russian troops—and who should therefore be destroyed. Without an understanding of the deepening influence of Tsarist imperial nationalism in Russia since 2012, and especially following Crimea’s annexation in 2014, scholars will be unable to grasp or explain why Putin has been so obsessed with returning Ukraine to the Russian World—a concept created as long ago as 2007 as a body to unite the three eastern Slavs, which underpinned his invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Putin’s invasion did not come out of nowhere, but had been nurtured, discussed, and raised by Putin and Russian officials since the mid-2000s in derogatory dismissals of Ukrainians, and in territorial claims advanced against Ukraine. Unfortunately, few scholars took these at face value until summer 2021, when Putin published a long 6,000-word article[2] detailing his thesis about Russians and Ukrainians constituting one people with a single language, culture, and common history.[3] Ukrainians were a ‘brotherly nation’ who were ‘part of the Russian people.’ ‘Reunification’ would inevitably take place, Putin told the Valdai Club in 2017.[4] The overwhelming majority of scholarly books and journals have dismissed, ignored, or downplayed Russian nationalism as a temporary phenomenon.[5] Richard Sakwa claimed Putin was not dependent upon Russian nationalism, ‘and it is debatable whether the word is even applicable to him.’[6] Other scholars described it as a temporary phenomenon that had disappeared by 2015–16.[7] A major book on Russian nationalism published after the 2014 crisis included nothing on the incorporation of Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré discourse that dismissed the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians.[8] Russia’s invasion of Ukraine backed by Russian nationalist rhetoric has led to many Western academics suggesting that the Russian forces have ended up—or will end up—with egg on their faces. Why they felt the need to take this angle has varied, ranging from elaborate political science theories popular in North America about the nature of the Russian regime to the traditional Russophilia found among a significant number of Euro-American scholars writing about Russia.[9] As Petro Kuzyk pointed out, in writing extensively about Ukrainian regionalism, scholars have tended to exaggerate intra-Ukrainian regional divisions. [10] This has clearly been seen during the invasion, when Russia has found no support among Russian-speakers in cities such as Kharkiv, Mariupol, Odesa, and elsewhere. Furthermore, the prevailing consensus prior to the invasion among scholars and think tankers was eerily similar to that in Moscow; namely, that Ukraine would be quickly occupied, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy would flee, and Kyiv would be captured by Russian troops. That this did not happen again shows a a serious scholarly miscalculation about the strength of Ukrainian identity, and an overestimation of the strength of Russian military power.[11] Nationalism in Putin’s Russia has integrated Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms into an eclectic ruling ideology that drives the invasion. Putin, traditionally viewed as nostalgic for the Soviet Union, has also exhibited some pronounced anti-Soviet tendencies, above all in criticising Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin for creating a federal union of republics that included ‘Russian lands’ in the south-east, and artificially creating a ‘fake’ Ukrainian people. Putin’s invasion goal of ‘denazification’[12] aimed to correct this mistake by destroying the ‘anti-Russia’ nurtured by the West.[13] Both scholars and Russian leaders have been baffled as to how to understand and explain the tenacity of Ukrainian identity that has fought the Russian army to a standstill, and is now in the position of launching counterattacks. What is particularly difficult for Russian political leaders and media journalists to explain is how a people that supposedly does not exist (Ukrainians) could greet the ‘special military operation’ (Putin’s dystopian term for the invasion of Ukraine) not with bouquets of flowers but met it with armed resistance. Instrumentalism: Russian Nationalism as a Temporary Phenomenon Sakwa[14] writes that ‘the genie of Russian nationalism was firmly back in the bottle’ by 2016. Pal Kolstø and Marlene Laruelle, along similar lines, write that the nationalist rhetoric of 2014 was novel and subsequently declined.[15] Meanwhile, Henry Hale[16] also believes Putin was only a nationalist in 2014, not prior to the annexation of the Crimea or since 2015. Laruelle[17] concurs, writing that by 2016, Putin’s regime had ‘circled back to a more classic and pragmatic conservative vision’. Laruelle describes Putin’s regime as nationalistic only in the period 2013–16, arguing that ‘since then [it] has been curtailing any type of ideological inflation and has adopted a low profile, focusing on much more pragmatic and Realpolitik agendas at home and abroad.’[18] Paul Chaisty and Stephen Whitefield write, ‘Putin is not a natural nationalist’ and ‘[w]e do not see the man and the regime as defined by principled ideological nationalism.’[19] Sakwa[20] is among the foremost authors who deny that Putin is a nationalist, describing him as not an ideologue because he remains rational and pragmatic—which sharply contrasts with an invasion that most commentators view as irrational. Allegedly, moreover, there has been a ‘crisis’ in Russian nationalism.[21] Other scholars, meanwhile, believed that Putin ‘lost’ nationalist support.[22] In reality, the opposite took place. Russian imperial nationalism deepened, penetrated even further into Russian society and became dominant in Putin’s regime during the eight years between the invasions of Crimea and Ukraine. Russian imperial nationalist denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians became entrenched and have driven the invasion of Ukraine. Patriots and Conservatives - Not Nationalists Scholars described Russian nationalists as ‘patriots’ and western-style ‘conservatives.’ In the same year that the constitution was changed to allow Putin to remain president until 2036, Laruelle writes ‘the Putin regime still embodies a moderate centrist conservatism.’[23] Petro, Sakwa, and Robinson analogously describe a ‘conservative turn’ in Russian foreign policy.[24] If contemporary British conservatives annexed part of Ireland and denied the existence of the Irish people, “conservatism” would no longer fully capture the ideology they represented. By the same token, the Putin regime’s annexation of Crimea and denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians has sharply steered Russian conservatism towards the conceptual centrality of imperial nationalism. In their analyses, Sakwa and Anna Matveeva could only identify ‘militarised patriotism’ or elites divided into ‘westerners’ and ‘patriots.’[25] Following his 2012 re-election, Sakwa writes that Putin only spoke of ‘Russian identity discourse’ and Putin’s ‘conservative values’ which he believes should be not confused with a Russian nationalist agenda.[26] Sakwa has generally avoided using the term ‘nationalist’ when discussing Russian politicians. This created problems in explaining why a ‘non-nationalist’ Putin might choose to support a wide range of far-right and a smaller number of extreme left political movements in Europe and the US, ranging from national-conservatives, populist-nationalists, irredentist imperialists to neo-Nazis in Europe. Sakwa[27] attempts to circumvent this conundrum by relying on a portfolio of euphemistic alternatives, describing these far-right and extreme left movements as ‘anti-systemic forces,’ ‘radical left,’ ‘movements of the far right,’ ‘European populists,’ ‘traditional sovereigntists, peaceniks, anti-imperialists, critics of globalisation,’ ‘populists of left and right,’ and ‘values coalition.’ Putin’s Imperial Nationalist Obsession with Ukraine The Soviet regime recognised a separate Ukrainian people, albeit one that always retained close ties to Russians. The Ukrainian SSR was a ‘sovereign’ republic within the Soviet Union. In 1945, Joseph Stalin negotiated three seats at the UN for the USSR (representing the Russian SFSR), Ukrainian SSR, and Belarusian SSR. In the USSR, there was a Ukrainian lobby in Moscow, while this has been wholly absent under Putin.[28] Soviet nationality policy defined Ukrainians and Russians as related, but nevertheless separate peoples; this was no longer the case in Putin’s Russia. In the USSR, Ukraine, and the Ukrainian language ‘always had robust defenders at the very top. Under Putin, however, the idea of Ukrainian national statehood was discouraged.’[29] Although the USSR promoted Russification, it nevertheless recognised the existence of the Ukrainian language. For a decade prior to the invasion, the Ukrainian language was disparaged by the Russian media and political leaders as a dialect that was artificially made a language in the Soviet Union.[30] Russian nationalist myths and stereotypes underpinning the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had been raised, discussed, and threatened for over a decade prior to the ‘special military operation’. When Putin returned as president in 2012, he portrayed himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian [i.e., eastern Slavic] lands.’ Ukraine’s return to the Russian World, alongside Crimea and Belarus, was Putin’s unfinished business that he needed to accomplish before entering Russia’s history books. Ukraine, as a ‘Russian land’, should fall within the Russian World and remain closely aligned to Russia. Ukrainians, on this account, had no right to decide their own future. Russia sought to accomplish Ukraine’s return to the Russian World through the two Minsk peace agreements signed in 2014–15. Ukrainian leaders resisted Russian pressure to implement the agreements because they would have created a weak central government and federalised state where Russia would have inordinate influence through its proxy Donetsk Peoples Republic and Luhansk Peoples Republic. The failure of Russia’s diplomatic and military pressure led to a change in tactics in October 2021. Early that month, former President Dmitri Medvedev, now deputy head of Russia’s Security Council, penned a vitriolic attack on Ukrainian identity as well as an anti-Semitic attack on Jewish-Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ruling out further negotiations with Kyiv.[31] Medvedev claimed Ukrainian leaders were US puppets, and that therefore the Kremlin needed to negotiate directly with their alleged ‘puppet master’—Washington. Meanwhile, Russia would ‘wait for the emergence of a sane leadership in Ukraine,’ ‘who aims not at a total confrontation with Russia on the brink of war…but at building equal and mutually beneficial relations with Russia.’[32] Medvedev was revealing that Russia’s goal in any future military operation would be regime change, replacing an ‘anti-Russia’ leadership with a pro-Kremlin leader.[33] In early November 2021, Russia’s foreign policy machine mobilised and made stridently false accusations about threats from Ukraine and its ‘Western puppet masters.’ Russia began building up its military forces on the Ukrainian border and in Belarus. In December 2021, Russia issued two ultimatums to the West, demanding a re-working of European security architecture. The consensus within Euro-American commentary on the invasion has been that this crisis was completely artificial. NATO was not about to offer Ukraine membership, even though Ukraine had held periodic military exercises with NATO members for nearly three decades, while the US and NATO at no point planned to install offensive missiles in Ukraine. The real cause of the crisis was the failure of the Minsk peace process to achieve Ukraine’s capitulation to Russian demands that would have placed Ukraine within the Russian sphere of influence. After being elected president in April 2019, Zelenskyy had sought a compromise with Putin, but he had come round to understanding that this was not on offer. The failure of the Minsk peace process meant Ukraine’s submission would now be undertaken, in Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s words, by ‘military-technical means’—that is, the ‘special military operation’ that began on 24 February 2022. Russian Imperial and White Émigré Nationalism Captures Putin’s Russia Downplaying, marginalising, and ignoring Russian nationalism led to the ignoring of Russian nationalism’s incorporation of Tsarist and White Russian émigré denials of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Marginal nationalism in the 1990s became mainstream nationalism in Russia in the 2000s under Putin when the ‘emergence of a virulent nationalist opposition movement took the mainstream hostage.’[34] The 1993 coup d’état against President Boris Yeltsin was led by a ‘red-brown’ coalition of pro-Soviet and far-right nationalists and fascists. The failure of the coup d’état and the electoral defeat of the Communist Party leader Gennadiy Zyuganov in the 1996 elections condemned these groups to the margins of Russian political life. At the same time, from the mid 1990s, the Yeltsin presidency moved away from a liberal to a nationalist foreign and security approach within Eurasia and towards the West. This evolution was discernible in the support given to a Russian-Belarusian union during the 1996 elections and in the appointment of Yevgeny Primakov as foreign minister. Therefore, the capture of Russia by the Soviet siloviki began with the Chairman of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Primakov, four years before the chairman of the Federal Security Service (FSB), Putin, was elected president. Under Primakov, Russia moved from defining itself as part of the ‘common European home’ to the country at the centre of Eurasia. Under Putin, the marginalised ‘red-brown’ coalition gradually increased its influence and broadened to include ‘whites’ (i.e., nostalgic supporters of the Tsarist Empire). Prominent among the ideologists of the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition was the fascist and Ukrainophobe Alexander Dugin, who has nurtured national-Bolshevik and Eurasianist political projects.[35] In the 2014 crisis, Dugin, then a professor at Moscow State University, stated: ‘We should clean up Ukraine from the idiots,’ and ‘The genocide of these cretins is due and inevitable… I can’t believe these are Ukrainians. Ukrainians are wonderful Slavonic people. And this is a race of bastards that emerged from the sewer manholes.’[36] During the 2000s the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition came to prominence and Putin increasingly identified with its denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians. Tsarist imperial nationalism was integrated with Soviet nostalgia, Soviet traditions and symbols and historical myths, such as the Great Patriotic War. Since the mid 2000s, only five years into his rule, Putin spearheaded the rehabilitation of the White Russian émigré movement and reburial of its military officers, writers, and philosophers in Russia. These reburials took place at the same time as the formation of the Russian World Foundation (April 2007) and unification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the émigré Russian Orthodox Church (May 2007). These developments supercharged nationalism in Putin’s Russia, reinforced the Tsarist element in the ‘red-white-brown’ coalition and fuelled the growing disdain of, and antipathy towards Ukraine and Ukrainians that was given state support in the media throughout the two decades before the invasion.[37] Putin personally paid for the re-burial of White Russian émigré nationalists and fascists Ivan Ilyin, Ivan Shmelev, and General Anton Deniken, who called Ukraine ‘Little Russia’ and denied the existence of a separate Ukrainian nation. These chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians were typical of White Russian émigrés. Serhy Plokhy[38] writes, ‘Russia was taking back its long-lost children and reconnecting with their ideas.’ Little wonder, one hundred descendants of White Russian émigré aristocrats living in Western Europe signed an open letter of support for Russia during the 2014 crisis. Putin was ‘particularly impressed’ with Ilyin, whom he first cited in an address to the Russian State Duma as long ago as 2006. Putin recommended Ilyin to be read by his governors, senior adviser Vladislav Surkov, and Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev. The intention was to use Ilyin’s publications in the Russian state programme to inculcate ‘patriotism’ and ‘conservative values’ in Russian children. Ilyin was integrated into Putin’s ideology during his re-election campaign in 2012 and influenced Putin’s re-thinking of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands;’ that is, integrating Belarus and Ukraine into the Russian World, and specifically his belief that the three eastern Slavs constituted a pan-Russian nation.[39] Laruelle has downplayed the importance of Ilyin’s ideology, writing that he did not always propagate fascism, and that Putin only quoted him five times.[40] Yet Putin has not only cited Ilyin, but also asked Russian journalists whether they had read Deniken’s diaries, especially the parts where ‘Deniken discusses Great and Little Russia, Ukraine.’[41] Deniken wrote in his diaries, ‘No Russian, reactionary or democrat, republican or authoritarian, will ever allow Ukraine to be torn away.’[42] In turn, Tsarist imperial nationalist and White Russian émigré denials of Ukraine and Ukrainians were amplified in the Russian media and in its information warfare for over a decade prior to the invasion. Ukraine and Ukrainians were mocked in the Russian media in a manner ‘typical in coloniser-colonised relationships.’[43] Russia and Russians were cast as superior, modern, and advanced, while Ukraine and Ukrainians were portrayed as backward, uneducated, ‘or at least unsophisticated, lazy, unreliable, cunning, and prone to thievery.’ As a result of nearly two decades of Russian officials and media denigrating Ukraine and Ukrainians these Russian attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians ‘are widely shared across the Russian elite and populace.’[44] This is confirmed by a March 2022 survey conducted by Russia’s last remaining polling organisation, the Levada Centre, which found that an astronomical 81% of Russians supporting Russian military actions in Ukraine. Among these supporters, 43% believe the ‘special military operation’ was undertaken to protect Russophones, 43% to protect civilians in Russian-occupied Donbas, 25% to halt an attack on Russia, and 21% to remove ‘nationalists’ and ‘restore order.’[45] Russian Imperial Nationalist Denigration and Denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians Russian imperial nationalist views of Ukraine began to reappear as far back as the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections, when Russian political technologists worked for pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych’s election campaign, producing election posters designed to scare Russian speakers in south-eastern Ukraine about the prospect of an electoral victory by ‘fascist’ and ‘nationalist’ Viktor Yushchenko. This was when Russia revived Soviet ideological propaganda attacks against Ukrainian nationalists as ‘Nazi collaborators.’ Putin’s cult of the Great Patriotic War has been intricately linked to the promotion of Russia as the country that defeated Nazism in World War II (this is not true as all the Soviet nations contributed to the defeat) and which today is fighting contemporary Nazis in Ukraine, Poland, the three Baltic states, and beyond. Ukraine’s four de-communisation laws adopted in 2015 were despised in Moscow for many reasons. The most pertinent to this discussion was one law that equated Nazi and Soviet crimes against humanity (which contradicted Putin’s cult of Stalin[46]) and another law that moved the terminology of Ukraine’s wartime commemorations from the 1941–45 ‘Great Patriotic War’ to ‘World War II’ of 1939–45.[47] One of the 2004 election posters, reproduced below, imagines Ukraine in typical Russian imperial nationalist discourse as divided into three parts, with west Ukraine as ‘First Class’ (that is, the top of the pack), central Ukraine as ‘Second Class’ and south-eastern Ukraine as ‘Third Class’ (showing Russian speakers living in this region to be at the bottom of the hierarchy). Poster Prepared by Russian Political Technologists for Viktor Yanukovych’s 2004 Election Campaign Text:Yes! This is how THEIR Ukraine looks. Ukrainians, open your eyes! The map of Ukraine in the above 2004 election poster is remarkably similar to the traditional Russian nationalist image of Ukraine reproduced below: Map of Russian Imperial Nationalist Image of Ukraine Note: From right to left: ‘New Russia’ (south-eastern Ukraine in red), ‘Little Russia’ (central Ukraine in blue), ‘Ukraine’ (Galicia in orange), ‘Sub-Carpathian Rus’ (green).

Putin’s Growing Obsession with Ukraine Ignored by Scholars Imperial nationalism came to dominate Russia’s authoritarian political system, including the ruling United Russia Party. Putin’s political system copied that of the late USSR, which in turn had copied East European communist regimes that had created state-controlled opposition parties to provide a fake resemblance of a multi-party system. In 1990, the USSR gave birth to the Liberal Democratic Party of the Soviet Union, becoming in 1992 the Liberal Democratic Party of the Russian Federation (LDPRF). Led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the LDPRF repeatedly made loud bellicose statements about Ukraine and the West. The LDPRF’s goal has always been to attract nationalists who would have otherwise voted for far-right political parties not controlled by the state. In the 1993 elections following the failed coup d’état, the LDPRF received 22.9% - more than the liberal Russia’s Choice Party (15%) and the Communist Party (KPRF). Under Putin, these state-sponsored political projects expanded to the extreme left through the national-Bolshevik Motherland Party, whose programme was written by Dugin, and the Just Russia Party, which was active in Russian-occupied Donbas. Putin’s authoritarian regime needs internal fifth columnists and external enemies. Domestically, these include opposition leaders such as Alexei Navalny, and externally ‘anti-Russia’ Ukraine and the West. Changes to the Russian constitution in summer 2020 extended the ability of Putin to remain president for fifteen years, but in effect made him president for life. Political repression and the closure of independent media increased after these changes, as seen in the attempted poisoning of Navalny, and grew following the invasion of Ukraine. In 2017, The Economist said it was wrong to describe Russia as totalitarian;[48] five years later The Economist believed Russia had become a totalitarian state.[49] A similar evolution has developed over whether Putin’s Russia could be called fascist. In 2016, Alexander J. Motyl’s article[50] declaring Russia to be a fascist state met with a fairly tepid reception. and widespread scholarly criticism.[51] Laruelle devoted an entire book to decrying Russia as not being a fascist state, which was ironically published a few weeks after Russia’s invasion.[52] By the time of the invasion, all the ten characteristics Motyl had defined as constituting a fully authoritarian and fascist political system in Russia were in place:

Fascists rely on projection; that is, they accuse their enemies of the crimes which they themselves are guilty of. This has great relevance to Ukraine because Russia did not drop its accusation of Ukraine as a ‘Nazi’ state even after the election of Zelenskyy, who is of Jewish-Ukrainian origins and whose family suffered in the Holocaust.[54] Indeed, civilian and military Ukrainians describe Russian invaders as ‘fascists,’ ‘racists’, and ‘Orks’ (a fictional character drawn from the goblins found in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings). After shooting and severely wounding a Ukrainian civilian, the Russian soldier stood over him saying ‘We have come to protect you.’[55] Another Russian officer said to a young girl captive: ‘Don’t be afraid, little girl, we will liberate you from Nazis.’[56] Putin and the Kremlin’s justification for their ‘special military operation’ into Ukraine was based on many of the myths and chauvinistic attitudes to Ukraine and Ukrainians that had been disseminated by Russia’s media and information warfare since the mid 2000s. Of the 9,000 disinformation cases the EU database has collected since 2015, 40% are on Ukraine and Ukrainians.[57] The EU’s Disinformation Review notes, ‘Ukraine has a special place within the disinformation (un)reality,’[58] and ‘Ukraine is by far the most misrepresented country in the Russian media.[59] Russia’s information warfare and disinformation has gone into overdrive since the 2014 crisis. ‘Almost five years into the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the Kremlin’s use of the information weapon against Ukraine has not decreased; Ukraine still stands out as the most misrepresented country in pro-Kremlin media.’[60] Since the mid 2000s, Russian media and information warfare has dehumanised Ukraine and Ukrainians, belittling them as unable to exist without external support.[61] In colonialist discourse, Ukrainians were mocked as dumb peasants who had no identity, did not constitute a real nation, and needed an ‘elder brother’ (US, Russia) to survive. Such discourse was reminiscent of European imperialists when discussing their colonies prior to 1945. Ukraine was repeatedly ridiculed as an artificial country and a failed, bankrupt state. Putin first raised this claim as far back as in his 2008 speech to the NATO-Russia Council at the Bucharest NATO summit.[62] Ukraine as a failed state is also one of the most common themes in Russian information warfare.[63] In 2014, the Ukrainian state allegedly collapsed, requiring Russia’s military intervention. The Ukrainian authorities were incapable of resolving their problems because Ukraine is not a real state and could not survive without trade with Russia. Russian disinformation claimed that Ukraine’s artificiality meant it faced territorial claims from all its neighbours. Central-Eastern European countries would put forward territorial claims towards western Ukraine. Russia has made territorial claims to south-eastern Ukraine (Novorossiya [New Russia] and Prichernomorie [Black Sea Lands]) since as far back as the 2008 NATO summit[64] and increased in intensity following the 2014 invasion of Crimea. Putin repeatedly condemned Lenin for including south-eastern Ukraine within the Soviet Ukrainian republic, claiming the region was ancient ‘Russian’ land.[65] Another common theme in the Russian media was that Ukraine was a land of perennial instability and revolution where extremists run amok, Russian speakers were persecuted, and pro-Russian politicians and media were repressed and closed. Ukrainian ‘nationalist’ and ‘neo-Nazi’ rule over Ukraine created an existentialist threat to Russian speakers. Putin refused to countenance the return of Ukrainian control over the Russian-Ukrainian joint border because of the alleged threat of a new ‘Srebrenica-style’ genocide of Russian speakers.[66] Putin used the empirically unsubstantiated claim that Russian speakers were subject to an alleged ‘genocide’ as justification for the ‘special military operation.’ On 16 March, the UN’s highest court, the International Court of Justice, threw out the Russian claim of ‘genocide’ and demanded Russia halt its war.[67] Putin and the Kremlin adopted the discourse of an artificial Ukrainian nation created as an anti-Russian conspiracy. Putin said: ‘The Ukrainian factor was specifically played out on the eve of World War I by the Austrian special service. Why? This is well-known—to divide and rule (the Russian people).’[68] Putin and the Kremlin incorporated these views of Ukraine and Ukrainians a few years after they had circulated within the extreme right in Russia. The leader of the Russian Imperial Movement, Stanislav Vorobyev said, ‘Ukrainians are some socio-political group who do not have any ethnos. They are just a socio-political group that appeared at the end of the nineteenth century by means of manipulation of the occupying Austro-Hungarian administration, which occupied Galicia.’[69] Vorobyev and Putin agreed with one another that ‘Russians’ were the most divided people in the world and believed Ukrainians were illegally occupying ‘Russian’ lands.[70] These nationalist myths were closely tied to another, namely that the West created a Ukrainian puppet state in order to divide the pan-Russian nation. Russia’s ‘special military operation’ is allegedly not fighting the Ukrainian army but ‘nationalists,’ ‘neo-Nazis and drug addicts’ supported by the West.[71] Putin has even gone so far as to deny that his forces are fighting the Ukrainian army at all, and has called on Ukrainian soldiers to rebel against the supposed ‘Nazi’ regime led by Zelenskyy—an especially cruel slur given that several generations of the latter’s family were murdered during the Holocaust. The Russian nationalist myth of a Ukrainian puppet state is a reflection of viewing it as a country without real sovereignty that only exists because it is propped up by the West. Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns also depicted dissidents and nationalists as puppets of Western intelligence services. Russian information warfare frequently described former President Petro Poroshenko and President Zelenskyy as puppets of Ukrainian nationalists and the West. [72] These Russian nationalist views have also percolated through into the writings of some Western scholars. Stephen Cohen, a well-known US historian of Russia and the Soviet Union, described US Vice President Joe Biden as Ukraine’s ‘pro-consul overseeing the increasingly colonised Kyiv.’[73] President Poroshenko was not a Ukrainian leader, but ‘a compliant representative of domestic and foreign political forces,’’ who ‘resembles a pro-consul of a faraway great power’ running a ‘failed state.’[74] Cohen, who was contributing editor of the left-wing The Nation magazine, held a derogatory view towards Ukraine as a Western puppet state, which is fairly commonly found on the extreme left in the West, and which blamed the West (i.e., NATO, EU enlargement) for the 2014 crisis, rather than Putin and Russia. Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns routinely attacked dissidents and nationalist opposition as ‘bourgeois nationalists’ who were in cahoots with Nazis in the Ukrainian diaspora and in the pay of Western and Israeli secret services. Ukraine has been depicted in the Russian media since the 2004 Orange Revolution as a country ruled by ‘fascists’ and ‘neo-Nazis.’[75] A ‘Ukrainian nationalist’ in the Kremlin’s eyes is the same as in the Soviet Union; that is, anybody who supports Ukraine’s future outside the Russian World and USSR. All Ukrainians who supported the Orange and Euromaidan Revolutions and are fighting Russia’s ‘special military operation’ were therefore ‘nationalists’ and ‘Nazis.’ Conclusion Between the 2004 Orange Revolution and Putin’s re-election in 2012, Russian imperial nationalism rehabilitated Tsarist imperial and White Russian émigré dismissals of Ukraine and Ukrainians into official discourse, military aggression, and information warfare. In 2007, the Russian World Foundation was created and two branches of the Russian Orthodox Church were re-united. Returning to the presidency in 2012, Putin believed he would enter Russian history as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands’ which he proceeded to undertake with Crimea (2014), Belarus (2020), and Ukraine (2022). The origins of Putin’s obsession with Ukraine lie in his eclectic integration of Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms. The former provides the ideological bedrock for the denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians while the latter provides the ideological discourse to depict as Nazis all those Ukrainians who resist being defined as Little Russians. Putin believed his military forces would be greeted as liberators by Little Russians eager to throw off the US imposed nationalist and neo-Nazi yoke, the artificial Ukrainian state would quickly disintegrate, and the country and capital city of Kyiv would be taken within two days. Russian troops brought parade uniforms to march down Kyiv’s main thoroughfare and victory medals to be awarded to troops. This was not to be, because Putin’s denial of a Ukrainian people is—put simply—untrue. The Russo-Ukrainian war is a clash between twenty-first century Ukrainian patriotism and civic nationalism, as evidenced by Zelenskyy’s landslide election, and rooted in a desire to leave the USSR behind and be part of a future Europe, and nineteenth-century Russian imperial nationalism built on nostalgia for the past. Unfortunately, many scholars working on Russia ignored, downplayed, or denied the depth, direction, and even existence of nationalism in Putin’s Russia and therefore find unfathomable the ferocity, and goals behind the invasion of Ukraine. This was because many scholars wrongly viewed the 2014 crisis as Putin’s temporary, instrumental use of nationalism to annex Crimea and foment separatism in south-eastern Ukraine. Instead, they should have viewed the integration of Tsarist imperial and Soviet nationalisms from the mid 2000s through to the invasion as a continuous, evolutionary process that has led to the emergence of a fascist, totalitarian, and imperialist regime seeking to destroy Ukrainian identity. [1] See Taras Kuzio, Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War: Autocracy-Orthodoxy-Nationality (London: Routledge, 2022). [2] Vladimir Putin, ‘Pro istorychnu yednist rosiyan ta ukrayinciv,’ 12 July 2021. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66182?fbclid=IwAR0Wj7W_7QL2-IFInLwl4kI1FOQ5RxJAemrvCwe04r8TIAm03rcJrycMSYY [3] Y.D. Zolotukhin, Bila Knyha. Spetsialnykh Informatsiynykh Operatsiy Proty Ukrayiny 2014-2018, 67-85. [4] Vladimir Putin, ‘Speech to the Valdai Club,’ 25 October 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvY184FQsiA [5] Anna Matveeva, A. (2018). Through Times of Trouble. Conflict in Southeastern Ukraine Explained From Within (Lanham, MA: Lexington Books, 2018), 182, 218, 221, 223, 224, 277. [6] Richard Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest. The Post-Cold War Crisis of World Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 125. [7] Pal Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again,’ Slavic Review, 75: 3 (2016), 702-725; Henry E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia,’ In: Pal Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud eds., The New Russian Nationalism. Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 221-248, at p.246; Marlene Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’ Journal of Democracy, 31: 3 (2020: 115-129. [8] P. Kolstø and H. Blakkisrud eds., The New Russian Nationalism. Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016). [9] For a full survey see T. Kuzio, ‘Euromaidan Revolution, Crimea and Russia-Ukraine War: Why it is Time for a Review of Ukrainian-Russian Studies,’ Eurasian Geography and Economics, 59: 3-4 (2018), 529-553 and Crisis in Russian Studies? Nationalism (Imperialism), Racism, and War (Bristol: E-International Relations, 2020), https://www.e-ir.info/publication/crisis-in-russian-studies-nationalism-imperialism-racism-and-war/ [10] See Petro Kuzyk, ‘Ukraine’s national integration before and after 2014. Shifting ‘East–West’ polarization line and strengthening political community,’ Eurasian Geography and Economics, 60: 6 (2019), 709-735/ [11] T. Kuzio, ‘Putin's three big errors have doomed this invasion to disaster,’ The Daily Telegraph, 15 March 2022. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/03/15/putins-three-big-errors-have-doomed-invasion-disaster/ [12] ‘Do not resist the liberation,’ EU vs Disinfo, 31 March 2022. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/do-not-resist-the-liberation/ [13] T. Kuzio, ‘Inside Vladimir Putin’s criminal plan to purge and partition Ukraine,’ Atlantic Council, 3 March 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/inside-vladimir-putins-criminal-plan-to-purge-and-partition-ukraine/ [14] R. Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 159. [15] P. Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again’ and M. Laruelle, ‘Is Nationalism a Force for Change in Russia?’ Daedalus, 146: 2 (2017, 89-100. [16] H. E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia.’ [17] M. Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’126. [18] M. Laruelle, ‘Ideological Complimentarity or Competition? The Kremlin, the Church, and the Monarchist Idea,’ Slavic Review, 79: 2 (2020), 345-364, at p.348. [19] Paul Chaisty and Stephen Whitefield, S. (2015). ‘Putin’s Nationalism Problem’ In: Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and R. Sakwa eds., Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives (Bristol: E-International Relations, 2015), 165-172, at pp. 157, 162. [20] R. Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine. Crisis in the Borderlands (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015) and Russia Against the Rest. [21] Robert Horvath, ‘The Euromaidan and the crisis of Russian nationalism,’ Nationalities Papers, 43: 6 (2015), 819-839. [22] P. Kolsto, ‘Crimea vs. Donbas: How Putin Won Russian Nationalist Support—and Lost It Again’ and H. E. Hale, ‘How nationalism and machine politics mix in Russia.’ [23] M. Laruelle, ‘Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism,’126. [24] R. Sakwa, ‘Is Putin an Ism,’ Russian Politics, 5: 3 (2020): 255-282, at pp.276-277; Neil Robinson, ‘Putin and the Incompleteness of Putinism,’ Russian Politics, 5: 3 (2020): 283-300, at pp.284-285, 287, 289, 293, 299); Nicolai N. Petro, ‘How the West Lost Russia: Explaining the Conservative Turn in Russian Foreign Policy,’ Russian Politics, 3: 3 (2018): 305-332. [25] A. Matveeva, Through Times of Trouble, 277 and Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 119. [26] R. Sakwa, Russia Against the Rest, 125, 189. [27] Ibid., 60, 75, 275, 276. [28] Mikhail Zygar, All the Kremlin’s Men. Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin (New York: Public Affairs, 2016), 87. [29] Ibid., [30] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ukrainian-literary-language-is-an-artificial-language-created-by-the-soviet-authorities/ [31] https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5028300 [32] Ibid., [33] Taras Kuzio, ‘Medvedev: The Russian-Ukrainian War will continue until Ukraine becomes a second Belarus,’ New Eastern Europe, 20 October 2021. https://neweasterneurope.eu/2021/10/20/medvedev-the-russian-ukrainian-war-will-continue-until-ukraine-becomes-a-second-belarus/ [34] Charles Clover, Black Wind, White Snow. The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), 287. [35] M. Laruelle, ‘The three colors of Novorossiya, or the Russian nationalist mythmaking of the Ukrainian crisis,’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 3: 1 (2016), 55-74. [36] Mykola Riabchuk, ‘On the “Wrong” and “Right” Ukrainians,’ The Aspen Review, 15 March 2017. https://www.aspen.review/article/2017/on-the-wrong-and-right-ukrainians/ [37] Anders Aslund, ‘Russian contempt for Ukraine paved the way for Putin’s disastrous invasion,’ Atlantic Council, 1 April 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russian-contempt-for-ukraine-paved-the-way-for-putins-disastrous-invasion/ [38] Serhy Plokhy, Lost Kingdom. A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin (London: Penguin Books, 2017), 327. [39] Ibid., 332. [40] M. Laruelle, ‘In Search of Putin’s Philosopher,’ Intersection, 3 March 2017. https:// www.ponarseurasia.org/article/search-putins-philosopher [41] S. Plokhy, Lost Kingdom, 326. [42] Ibid., [43] Alena Minchenia, Barbara Tornquist-Plewa and Yulia Yurchuk ‘Humour as a Mode of Hegemonic Control: Comic Representations of Belarusian and Ukrainian Leaders in Official Russian Media’ In: Niklas Bernsand and B. Tornquist-Plewa eds., Cultural and Political Imaginaries in Putin’s Russia (Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2018), 211-231, at p.225. [44] Ibid, 25 and Igor Gretskiy, ‘Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy – The Case of Ukraine,’ Saint Louis University Law Journal, 64:1 (2020), 1-22, at p.21. [45] https://www.levada.ru/2022/03/31/konflikt-s-ukrainoj/ [46] T. Kuzio, ‘Stalinism and Russian and Ukrainian National Identities,’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 50, 4 (2017), 289-302 . [47] Anna Oliynyk and T. Kuzio, ‘The Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity, Reforms and De-Communisation in Ukraine,’ Europe-Asia Studies, 73: 5 (2021), 807-836. [48] Masha Gessen is wrong to call Russia a totalitarian state,’ The Economist, 4 November 2017. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2017/11/02/masha-gessen-is-wrong-to-call-russia-a-totalitarian-state [49] ‘The Stalinisation of Russia,’ Economist, 12 March 2022. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/03/12/the-stalinisation-of-russia [50] Alexander J. Motyl, ‘Putin’s Russia as a fascist political system,’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 49: 1 (2016), 25-36. [51] I was guest editor of the special issue of Communist and Post-Communist Studies and remember the controversies very well as to whether to publish or not publish Motyl’s article. [52] M. Laruelle, Is Russia Fascist ? Unraveling Propaganda East and West (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2022). [53] Olga Kryshtanovskaya and Stephen White, ‘Putin's Militocracy,’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 19: 4 (2003), 289-306. [54] Zelenskyy is the grandson of the only surviving brother of four. The other 3 brothers were murdered by the Nazi’s in the Holocaust. [55] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/19/we-have-to-come-to-protect-you-russian-soldiers-told-ukrainian-man-theyd-shot [56] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/20/world/europe/russian-soldiers-video-kyiv-invasion.html [57] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-will-turn-into-a-banana-republic-ukrainian-elections-on-russian-tv/?highlight=ukraine%20land%20of%20fascists [58] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/what-didnt-happen-in-2017/?highlight=What%20didn%26%23039%3Bt%20happen%20in%202017%3F [59] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-under-information-fire/ [60] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-under-information-fire/?highlight=ukraine [61] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/dehumanizing-disinformation-as-a-weapon-of-the-information-war/?highlight=Ukraine%20has%20a%20special%20place%20within%20the%20disinformation%20%28un%29reality [62] https://www.unian.info/world/111033-text-of-putin-s-speech-at-nato-summit-bucharest-april-2-2008.html [63] Yuriy D. Zolotukhin Ed., Bila Knyha. Spetsialnykh Informatsiynykh Operatsiy Proty Ukrayiny 2014-2018 (Kyiv: Mega-Pres Hrups, 2018), 302-358. [64] https://www.unian.info/world/111033-text-of-putin-s-speech-at-nato-summit-bucharest-april-2-2008.html [65] T. Kuzio, Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War,1-34. [66] ‘Putin fears second “Srebrenica” if Kiev gets control over border in Donbass,’ Tass, 10 December 2019. https://tass.com/world/1097897 [67] https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/182 [68] V. Putin, ‘Twenty questions with Vladimir Putin. Putin on Ukraine,’ Tass, 18 March 2020. https://putin.tass.ru/en [69] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZD62ackWGFg [70] V. Putin, ‘Ukraina – samaya blyzkaya k nam strana,’ Tass, 29 September 2015. https://tass.ru/interviews/2298160 and ‘Speech to the Valdai Club,’ 25 October 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvY184FQsiA [71] ‘Putin references neo-Nazis and drug addicts in bizarre speech to Russian security council – video,’ The Guardian, 25 February 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2022/feb/25/putin-references-neo-nazis-and-drug-addicts-in-bizarre-speech-to-russian-security-council-video [72] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/zelenskyys-ruling-is-complete-failure-nazis-feel-well-ukraine-remains-anti-russia/ [73] Stephen Cohen, War with Russia?: From Putin & Ukraine to Trump and Russiagate (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2019), 145. [74] Ibid., p. 36. [75] https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-will-turn-into-a-banana-republic-ukrainian-elections-on-russian-tv/?highlight=ukraine%20land%20of%20fascists by Juliette Faure

Since the mid-2010s, ‘tradition’ has become a central concept in political discourses in Russia. Phrases such as ‘the tradition of a strong state’, ‘traditional values’, ‘traditional family’, ‘traditional sexuality’, or ‘traditional religions’ are repeatedly heard in Vladimir Putin’s and other high-ranking officials’ speech.[1] Paralleling a visible conservative rhetoric hinging on traditional values, the Russian regime demonstrates a clear commitment to technological hypermodernisation. The increased budget for research and development in technological innovation, together with the creation of national infrastructures meant to foster investments in new technologies such as Rusnano or Rostec, and the National Technology Initiative (2014) show a firm intent from the regime.