by Emily Katzenstein

Emily Katzenstein: You describe your own work in terms of ‘decolonising urban spaces’ through artistic interventions. Can you tell us what that decolonisation means in this context? What projects are you currently working on?

Yolanda Gutiérrez: At the moment, I have two different kinds of projects. One is the Urban Bodies Projects. That’s a project that deals with the colonial past of European cities. I am working with local dancers in each city. The next one will be in Mexico City, and then one, next year, in Kigali. My second project is the Decolonycities Project. That’s a project about dealing with the German colonial past in the city of Hamburg, through the eyes of those who were colonised. I am planning to do five projects in five countries—Togo, Cameroon, Tanzania, Namibia, and Rwanda [countries Germany colonised in the late 19th and early 20th century—eds.] And then I have the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project, which I started when this Bismarck controversy arose. In Hamburg, they are renovating the Bismarck monument for €9 million. It became a big controversy and overlapped with the Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S., and here in Germany. Here in Hamburg, activists started to paint or graffiti all kinds of colonial monuments and symbols of white supremacy. Suddenly, overnight, these monuments had been altered. But you can’t really do that with the Bismarck statue because they’re currently renovating it and it’s surrounded by protective walls. So, we’ve been having a two year long discussion about what should happen with the Bismarck monument. The discussion in Hamburg was driven by a lot of activists, especially people of colour. For me, however, it was important to see what would happen if we brought in the perspectives of artists from former German colonies (Namibia, Cameroon, Togo, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania—eds.) who are living with the consequences of Bismarck’s role in Germany’s colonial past. So I acted as a producer and curator, and I invited artists from the countries that Germany colonised in Africa to stage their own performances in Hamburg, at historical sites that are linked to Germany’s colonial past. The artists who participated were Isack Peter Abeneko[1], Dolph Banza, Vitjitua Ndjiharine, Stone, Moussa Issiaka, Fabian Villasana aka Calavera, Sarah Lasaki, Faizel Browny, Samwel Japhet, and Shabani Mugado. That’s a political statement. When the invited artists put themselves in the spaces that have some significance in Germany’s colonial history, they appropriate those spaces. The artists put on performances that reinterpreted the meaning of the places in which they performed. During the International Summer Festival, when the invited artists from Bismarck-Dekolonial put on their performances, for example, the audience could participate in what I call a decolonising audio-walk: you could see the artists’ performance while simultaneously listening to an audio track that plays the sounds of German troops leaving the Hamburg port, for example—a huge event at the time. So, the audio of German troops leaving from the Hamburg port is juxtaposed with the performance of the artists from Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Cameroon. You are listening to an audio track about the event of German colonial troops leaving from the Hamburg port, and, simultaneously, you see the performances of artists who are descendants of those who were most directly affected by Germany’s colonial policy. We often tend to think of history as something stale, dead—something that belongs in the past, that we don’t care about. In discussions of Germany’s colonial past, that is a reaction that you encounter quite often. People say: That’s in the past and there is nothing that we can do about it. The past cannot be undone. And my reaction is: Yes, the past cannot be undone but we can change the perspective of how we look at history. EK That is something that brings the different contributions of this series together—the sense that the past is, in a sense, contemporaneous, and that the stories that we tell about the past are crucial to our sense of who we are today. Can I come back to the question I asked earlier? What does decolonisation mean when it comes to artistic interventions? How do you conceive of decolonisation in your own work? YG: Yes, my work reflects on the fact that history has been written by the colonisers. For hundreds of years, the colonial gaze has shaped our understanding of the societies that Europeans colonised. For example, during the Spanish conquest of Latin America, Spanish priests often took on the role of historians. Their impressions of the societies they encountered was heavily influenced by the own cultural presuppositions. For example, they had certain notions about the role of women in society, notions about gender roles, etc. That coloured and distorted their view of the societies they tried to describe. In the case of women in Aztec society, for example, they confused expectation and reality, and described what they expected to find—they portrayed Aztec women as unemancipated and occupying a predominantly domestic role, because that’s the way they saw the role of women in Catholic Spain. But now there are new histories of indigenous societies. There was an amazing exhibition in the Linden Museum Stuttgart on Aztecs culture, for example, that reflected very critically on the ways of seeing that have shaped European impressions of Aztec society over generations. That is what I am trying to do in terms of my artistic interventions—to publicise and communicate ‘unwritten’ histories, untold stories, and marginalised historical perspectives. To do that, I work closely with historians. For example, my most recent project is situated in Namibia, which was colonised by Germany in the late 19th and early 20th century. From the beginning, I’ve collaborated with Jan Kawlath, a doctoral student in history at the University of Hamburg. His PhD investigates how the departure of German colonial troops was publicly celebrated to performatively construct images of Germany as a colonial power. And when we visit the historical sites at which we will stage performances, we listen to his writings about events that took place there, and his writing about these places and sites informs our choreography. In that sense, my work is influenced by Gloria Wekker’s work on the cultural archive.[2] Wekker writes so powerfully about the importance of the cultural archive. There’s also a James Baldwin quote that captures it well: “History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals.”[3] EK: In your work, you’ve experimented with different modes of presentation and media to stage decolonising artistic interventions. You already mentioned the ‘decolonising audio-walk’. Can you explain the concept of a decolonising audio walk? YG: Yes, I use the concept of decolonising audio walks in all my projects. The audience has head-phones, and walks to historical sites that have some significance in the colonial past of the city. When you arrive at a site, you see the performance while listening to the audio soundtrack. It is a combination of different types of information, historical facts, interviews with experts, statements by artists, music, etc. etc. Afterwards, you walk to the next site, and so on. It is a way to incorporate a lot of different elements: Dance, audio—it’s an embodied experience for the audience because they walk through the city. Walking through the city allows you to see familiar places with new eyes. I mean, normally, once you’ve lived in a city for a while, you assume you know the place and you’re not going to go on a tour of the city. But then, during the decolonising audio walk, you experience yourself not knowing the city that you assumed you knew, and that allows you to uncover the histories that are normally not talked about. EK On the website of the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project, you raise a question that I found fascinating, and that I wanted to put to you: namely, what kinds of artistic interventions are effective in contributing to decolonising urban spaces? How do you think about the different artistic strategies and interventions one can stage, and about the differences in the impact they have? With regards to the ‘decolonising audio-walk’, is there a tension between this momentary performative intervention and the monuments that embody permanence? Can performances effectively contest the built environment? YG: Performances in urban spaces are a way to reach people easily. By contrast, universities have, for a couple of years, been doing a lot of “Ringvorlesungen” (series of lectures by different speakers), where you have artists and academics talk to each other about decolonisation. I have been following all these discussions, and I think that’s also an interesting approach, but they don’t reach a broad audience. Similarly, in the arts, there are many exhibitions that deal with decolonisation, but they are framed in a very particular way, and it’s for a particular audience; they don’t reach as many people. And what I really love about dance is that it allows me to juxtapose different temporalities and sensory impressions—historical accounts or sounds from the past are juxtaposed with a performance that’s very much in the moment. You can connect the history to which you are listening to what you see. In that sense, it’s a way to demonstrate the contemporaneity of the past. It’s like puzzle pieces coming together. But audio walks, and performances more generally, are ephemeral, and that is my big challenge. You can put on as many performances as you like—for example, during the International Summer Festival 2021 in Hamburg, we put on five performances every day, which was already a lot. But even if you do a hundred performances per day, it doesn’t change the fact that it is ephemeral. So right now, my big question is how we can turn this into something more permanent. Because it’s all about memory, right? It’s about memorials and historical sites that need to be decolonised. And the challenge for me is: How can I, as an artist in the performing arts, leave a print that’s permanent? I am trying to get ‘into memory’ and I am still trying to figure out how far we can go with these performances and audio-walks in historical sites, what their impact is. So that’s my big next challenge. I always say that the fact that the artists who participated in the Bismarck-Dekolonial Project—Isack Peter Abeneko, Dolph Banza, Vitjitua Ndjiharine, Stone, Moussa Issiaka, Fabian Villasana aka Calave, Sarah Lasaki, Faizel Browny, Samwel Japhet, and Shabani Mugado—put on these performances around the Bismarck monument means that the space has been altered. It is no longer the same space, no longer holds the same meaning. The traces they left are ephemeral but they are there, nonetheless. There is a trace. That’s why I want to work on putting up a QR code or something similar. At the moment, my idea is to combine it with a visually appealing sculpture or something else that attracts passers-by, so that they say: “What’s that? I want to know more.” And then they can use the QR code to watch the performance that happened in the space. EK: One of the questions that always structures debates about contested monuments, it seems to me, is how we should think about the relationship between meaning and monuments. As an artist, how do you think about this relationship between monuments and meaning? Can we speak of a ‘hegemonic’ meaning of particular monuments or should we think about a multiplicity of meanings? Should we oppose hegemonic meanings with counter-hegemonic meanings, or prioritise showcasing the diversity and multiplicity of possible interpretations and meanings? What’s your approach to this? YG: In Germany, we haven’t spent enough time reflecting Germany’s colonial past. The Second World War is obviously a horrific part of Germany’s history, and it tends to overshadow everything else, including Germany’s colonial past. But that means that you miss crucial connections, and that people don’t know Germany’s colonial past. For example, that the idea of the concentration camps was first developed during the genocide of the Herero and Nama in Namibia, camps that were built in the beginning of the 20th century. For me, the representation of Bismarck is a symbol of the power that Germany had in the world at that time. In the case of Bismarck, this is dangerous, because it works as a magnet for the right-wing, and we experienced that in a very, very bad way. During the performance of Vitjitua Ndjiharine, a visual artist from Namibia, one person in the audience suddenly went up to her and gave the Hitlergruß. He was facing the Bismarck monument, and stood in front of her, and gave the Hitlergruß. So, trying to deal with this statue and with what it represents is exactly where the power is, for me. I mean, just look at it. The sheer measure of the monument is so imposing. And I think that’s the way that Germans were feeling when they colonised Namibia. If you read the writings of German colonial officials at the time, there is this feeling of supremacy. And that’s difficult to deal with, especially now, when they are polishing the Bismarck monument and literally making it whiter. EK: There have been many proposals as to what should happen with the Bismarck monument. Some have argued that the monument should be removed altogether, others have argued that it should be turned on its head, and yet others propose letting it crumble. I assume letting it crumble is not really an option for safety reasons, but I’ve always liked the symbolism of it. What do you think should happen with the monument? YG: I think if you vanish the Bismarck monument that doesn’t mean that you’ve vanished the meaning of Bismarck in the minds of people; what his figure means for people. And you can’t simply let the monument crumble—the size of the monument means that that is unfeasible. There were issues with the static of the monument, that’s why they’re renovating it. I mean with some monuments, you can let them crumble, no problem, but given the size of the Bismarck monument that’s not feasible. But you know what? I could see it happening in a video, a video that’s then projected unto the Bismarck monument. That’s something that we have experimented with, too. We didn’t pull the statue down but we did what we call ‘video mapping.’ We did it at night, and that’s when I really felt like an activist. I had a generator, and it was midnight, and we had to set everything up. That’s the first time where I had to inform the municipality and said: Hey, I'm going to do this at the Bismarck monument. And they said, OK, that’s fine. You're going to destroy it. Nothing is going to happen. But I mean, you could see the change—suddenly the Bismarck monument became the canvas instead of the symbol it usually represents. Of course, that’s a temporary intervention. But I am also convinced that we need a permanent artistic intervention. I think we need an open space for discussions. For example, I could imagine a garden around the monument, a place where we can keep this dialogue and this discussion going once the renovation is done. I am not a visual artist, obviously, but I was on a podium discussion[4] about decolonising and recontextualising the Bismarck statue with several other artists. There were two very interesting women, Dior Thiam, a visual artist from Berlin, and Joiri Minaya, a Dominican- American artist based in New York. Joiri Minaya has already covered two colonial statues at the port of Hamburg, a statue of Vasco da Gama and a statue of Christopher Columbus, with printed fabrics of her own design[5]—it’s very interesting work. As I said, I am not a visual artist, but I think that a permanent art intervention is necessary. Because what I do is so ephemeral, and I have the sense that we need to reach as broad an audience as possible. EK: The discussions about what to do with the Bismarck monument have been ongoing for the last two years. What impact has the debate had? Do you get the sense that the debate has contributed to a broader political awareness of Bismarck’s role in Germany’s colonial past in Hamburg? Or is this largely a debate amongst a relatively narrow set of actors? YG: Yes, the question about impact. What I got tired of were all these discussions on advisory boards, and advisory committees: People discuss a lot. I am a maker, and I sat at a lot of these discussions and said, yes, we can keep discussing but we also need to do something now. And people had a lot of reasons for why we couldn’t do anything until later. But to me it seemed wrong to wait until the renovations are finished. It seemed like a strange idea to stage an intervention once Bismarck’s shining in all his glory, you know. The discussions are good and all, but they are not enough. They don’t reach enough people; they don’t reach communities. I think it would be fantastic to have something like the project Monument Lab in the United States here in Germany. Monument Lab is combination of different layers of communities—they bring together artists, activists, municipal agencies, cultural institutions, and young people. That’s precisely what we need to do around the Bismarck statue. We need a multilayered participatory process that includes different groups in society. [1] Due to pandemic-related travel restrictions, Isack Peter Abeneko could only participate remotely from Dar es Salaam. [2] Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham, 2016. [3] As cited in I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck (2016; New York: Magnolia Pictures, 2017), Netflix. (1:26:32). [4] Behörde für Kultur und Medien Hamburg, “(Post) colonial Deconstruction: Artistic interventions towards a multilayered monument”, 16.09.2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6215&v=hRFzASv_ea4&feature=emb_logo [5] For images of the covered statues and an explanation about the symbolism of the printed fabrics, see the link above at 1:25-1:30. by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. by Luke Martell

Following the explosion of the internet since the 1990s, and of smartphones and the growth of big tech corporations more recently, the politics of the digital world has drawn much attention. The digital commons, open access and p2p sharing as alternatives to enclosures and copyrighting digitally are important and have been well covered, as providing free and open rather than privatised and restricted online resources.[1] Free and open-source software (FOSS) has been important in projects in the Global South.[2] Also discussed has been the use of social media in uprisings and protest, like the Arab Spring and the #MeToo movement. There is consideration of the anxiety of some when they are not connected by computer or phone, which raises questions of the right or perceived obligation to be connected and, on the other hand, the benefits of digital detox. There are many other important analyses in the digital politics literature about matters such as expression, access, equality, the digital divide, power, openness, and innovation.[3] I focus here on alternatives in the light of recent surveillance and privacy concerns that have come to the fore since the Snowden affair in 2013, the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018, and the Pegasus spyware revelations in 2021. US intelligence whistleblower Edward Snowden exposed widespread phone and internet surveillance by US and other security agencies. The firm Cambridge Analytica collected extensive personal data of tens of millions of Facebook users, without their consent, for political advertising, although they may have exaggerated what they did or were able to. The NSO technology company were found to have installed Pegasus surveillance spyware on the phones of politicians, journalists, and activists for number of states. There have been numerous hacks and mega-leaks of individual and company data.

Big tech corporations like GAFAM—Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Facebook (Meta), Apple, and Microsoft—have come to dominate and create oligopolies in the digital and tech worlds (another acronym FAANG includes Netflix but not Microsoft). More internationally communications social media like WeChat, Line, Discord, and QQ have become pervasive. GAFAM have an extensive hold over sectors such that we are constrained inside their walled gardens to get the online services we want or have come to rely on. Google is a prominent example; it is difficult, for instance, to operate an Android phone without using them, the company’s early motto ‘Don’t be Evil’ not to be seen any more these days. These companies’ oligopolies over tech and the digital are of concern because they limit our ability to choose and be free, and so is their invasion of personal spaces with surveillance and the capturing of personal information. Many of the corporations gather information about our digital activities, searches, our IP addresses, interests, contacts, and messaging, using algorithmic means. The information is captured and aggregated, and value is created from surveillance, the extractive process of data mining, the selling of personal information, and the creation of models of user behaviour for directing advertising and nudging. In this system, it is said, the user or consumer is the product, the audience the commodity. Data is seen as the new oil, where the oil of the digital economy is us. The produce is the models created to manipulate consumers. We are often so reliant on such providers it is difficult to avoid this information being collected, something done in a way which is complex and opaque, so hard for us to see and respond to. It is often in principle carried out with our consent but withdrawing consent is so complicated and the practices so obscure and normalised for many that in effect we are giving it without especially wanting to. The information gathered is also available on request, in many cases to varying degrees in different contexts, to governments and police. Sometimes states use the corporate databases of companies like Palantir, avoiding legal restrictions on government use of citizen data, especially in the USA, to monitor some of the most mainstream, benign, and harmless groups and individuals. There are reports of a ‘chilling effect’ where people are hesitant about saying things or using online resources like searches in a way they feel could attract unjustified government attention. Questioning approaches to this situation have focused on critique, and action has homed in on boycotts, e.g. of platforms like Facebook, and more general disconnection and unplugging. There is a ‘degoogling’ movement of people who wish to go online and use the Internet, computers and smartphones in ways that avoid organisations like Google. For many, degoogling (or de-GAFAMing) is a complex process, technically and in the amount of work and time involved. Privacy concerns are also followed through by the avoidance of non-essential cookies and using tracking blockers, encryption, and other privacy tools like browser extensions and Virtual Private Networks. Apple builds privacy and blocking means into its products to the consternation of Facebook who have an advertising-led approach. Mozilla has taken a lead in making privacy tools available for its Firefox browser and beyond. At state level, responses have been oriented to attempting to limit monopolisation and ensure competition, although these have not stopped oligopolies in digital information and tech. There is variation internationally in anti-monopoly attempts by states or the supranational EU. States have varying privacy laws limiting access to personal information digitally, with governments like the Swiss being more rigorous and outside the ‘eyes’ states that share intelligence, while states like the Dutch have moved from stronger to weaker privacy laws. The ‘five eyes’ states Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and USA have a multilateral agreement to spy on citizens and share the collected intelligence with one another. So, those beyond the ‘eyes’ states are not obligated to sharing citizens’ private data at the request of other powers. EU GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) legislation is important in this context. The radical politics of alternatives in the Arab Spring, and the Occupy and anti-austerity movements have often relied on social media such as Twitter to organise and act. Many in such movements believe in independence and autonomy including in conventional media but do not go much beyond critique to digital alternatives, which can remain the preserve still of the tech-minded and committed. The latter sometimes have a political critique and approach but often just privacy concerns within an effectively liberal or libertarian approach. One approach, ‘cyber-libertarianism’, is against obstacles to a free World Wide Web, such as government regulation and censorship, although Silicon Valley that it is identified with is also quite liberal, in the USA sense, and concerned with labour rights. An emphasis of activists on openness and transparency can be given as reason for not using means, such as encryption and other methods mentioned above, for greater privacy and anonymity in information and communication. There is less expansion beyond critique, boycotting and evasion of privacy incursions to alternatives. However, alternatives there are, and these involve decentralised federated digital spaces where individuals and groups can access internet resources for communication and media from means that are alternative to GAFAM and plural, so we are not reliant on single or few major corporations. Some of these alternatives promise greater emphasis on privacy, not collecting or supplying our information to commerce or the state and, to different degrees, encryption of communication or information in transit or ‘at rest’, stored on servers. In some cases, encryption in alternatives is not much more extensive than through more mainstream providers, but we are assured on trust that that our data will not be read, shared, or sold. Many alternatives build free and open-source software provided not for profit or gain and sometimes, but not always, by volunteers. Code is open source rather than proprietary so we can see and access it and assess how the alternatives operate and can use and adapt the code. Some provide alternatives to social media like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit (such as Mastodon, Diaspora, and Lemmur) and to mainstream cloud storage, messaging (e.g., Signal) and email, although some of the alternative fora have low levels of users and activity and many critical and alternatives-oriented activists are still pushed to using big corporate suppliers for quantity of content and users. Groups like Disroot, a collective of volunteers, provide alternative email which limits the collection, storage and sharing of personal details. Disroot offers links to many platforms alternative to the big corporations for email, messaging, chatting, social media and cloud hosting. Groups like Riseup, a leftist and activist platform, provide invite-only email, data storage on their own servers, and other means for digital activity beyond big corporations and prying eyes to whom they intend to not divulge information, although sometimes limited by levels of encryption and the laws of the states where they are sited. Email providers like Protonmail and Tutanota promise not to collect information about users and to encrypt our communication more rigorously so we can avoid both GAFAM and surveillance. Some of these are still capitalist corporations, but with a privacy emphasis, although semi-alternative companies like Runbox and Infomaniak are worker-owned. Autistici, like Disroot, is volunteer-run on non-capitalist lines, monetary aspects limited to voluntary donation. Both have an anarchist leaning, Autistici more explicitly committed to an autonomous anti-capitalist position. Some alternative providers (like Runbox, Tutanota, and Posteo) have green commitments, using renewable energy to reduce carbon emissions. Others go beyond a corporate form and have more of a social movement identity. There are campaigning organisations that focus on digital rights and freedom, and crypto-parties that help people adopt privacy and anonymity means in their digital activity. Some alternative privacy-oriented platforms gained more attention and users after the Snowden affair, but many otherwise alternatives-oriented people continue to use providers like Google because they do not know about the alternatives or switching to them is, sometimes justifiably, seen as a big job. Others are resigned to the belief that email and such online activity can never be private or take alternative tracking blocking measures while continuing to use mainstream resources in, for example, email. For some users there is much to be gained by what data harvesting allows, for instance personalisation of content and making connections with others across platforms like Facebook and Instagram, or they feel that most of the data collected is trivial for them and so accepted. In such cases the dangers and morality of data harvesting and selling are not worrying enough to resist or avoid it. There may also be less individualistic benefits for social research and improvement of tech and the digital that, for some, make some of the data gathering outweigh privacy incursions. Many of the alternatives are at the level of software and online providers, but this leaves the sphere of hardware and connectedness, where it is possible for states to stop resistance and rebellion by turning the internet off or censoring it, as in China, Egypt, and Iran amongst many other cases. There are alternatives for hardware, for instance in the open-source hardware movement, and for connectedness through devices linked independently in infrastructure or mesh networks. Interest in these lags behind that in software alternatives and their effectiveness depends on how many join such networks.[4] So, the alternatives are around a politics of privacy, independence and autonomy alongside anti-monopoly and sometimes non-capitalist and green elements. It has been argued that the digital world as it is requires the insertion of concepts of anonymity[5] alongside concerns such as equality, liberty, democracy, and community in the lexicon of political ideas and concerns, and anonymity rather than oft advocated openness or transparency, a key actor in digital alternatives having been the network ‘Anonymous’. While anonymity is desirable, just as it is when wished for in the offline world, it faces limits in the face of what has been called ‘surveillance capitalism’.[6] Firstly, this is because, as offline, anonymity and privacy are difficult to achieve if faced with a determined high-level authority like a government, as the Snowden and Pegasus affairs showed. Secondly, seeking anonymity is a reactive and evasive approach. For a better world what is needed is resistance and an alternative. Resistance involves tackling the power of big tech and the capturing of data they are allowed. Via social movements and states this needs to be challenged and turned back. And in the context of alternatives, alternative tech and an alternative digital world needs to be expanded. So, implied is a regulated and hauled back big tech and its replacement by a more plural tech and digital world, decentralised and federated. One advocate of the latter is Tim Berners-Lee, credited as the founder of the World Wide Web. Anonymity may be desirable individually and for groups, but collectively what is required is overturning of big intrusive tech by state power, through regulation, anti-monopoly activity and public ownership. The UK Labour Party went into the 2019 General Election with a policy of nationalising broadband, mainly for inclusivity and rights to connectedness reasons, but opening up the possibility of other ends public ownership can secure. But state power can be a problem as well as a tool so the alternative of decentralised, collectivist, democratic tech is needed too in a pluralist digital world. So, to recap and clarify key points. Oligopoly and the harvesting and selling of our digital lives has become a norm and a new economic sector of capitalism. State responses, to very different degrees, have been to resist monopolisation and ensure modest privacy protections or awareness. Individual responses and those of some organisations have been to use software that blocks tracking and aims to maintain privacy and anonymity. But positive as these methods are, they are in part defensive, limited in what they can achieve against high-level attempts at intrusion, and some of these individualise action. Alongside such state and individual processes, we need a more pro-active and collective approach. This includes stronger regulation and breaking up and taking tech into collective ownership. In the sphere of alternatives, it means expanding and strengthening a parallel sphere, decentralised and federated. And alternatives require putting control in the hands of those affected, so collective democracy with inclusive participation. Then oligopolies are challenged and there is a link between those affected and those in control. But alternatives must be made accessible and more easily understandable to the non-techy and beyond the expert, and do not just have to be an alternative but can be a prefigurative basis for spreading to the way the digital and tech world is more widely. This involves supplementing liberal individual privacy and rights approaches, often defensive within the status quo, with collective democracy and control approaches, more proactive and constructive of alternatives[7]. If there is an erosion of capitalism out of such an approach so there will be also to profit incentives in surveillance capitalism. With an extension of collective control not-for-profit, then motivations for surveillance and data capture are reduced. But this must be done through inclusive democratic control (by workers, users and the community) as much as possible rather than the traditional state, as the latter has its own reasons for surveillance. It should be supplemented by a pluralist, decentralised, federated, digital world to counter oligopoly and power. Democratisation that is inclusive globally is also suited to dealing with differences and divides digitally, e.g. by class or across the Global North and Global South. Taken together this approach implies pluralist democratic socialism as well as liberalism, rather than capitalism or the authoritarian state. I am grateful to David Berry for his very helpful advice on this article. [1] Berry, D. (2008) Copy, Rip, Burn: The Politics of Copyleft and Open Source, London: Pluto Press. [2] Pearce, J (2018) Free and Open Source Appropriate Technology, in Parker, M. et al (eds) The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, London: Routledge. [3] For a good overview and analysis of the area see Issin, E. and Ruppert, E. (2020) Being Digital Citizens, London: Rowman and Littlefield. See also Bigo, D., Issin, E., and Ruppert, E. (eds) (2019) Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London: Routledge, and Muldoon, J. (2022) Platform Socialism: How to Reclaim our Digital Future from Big Tech, London: Pluto Press. [4] See Lopez, A. and Bush, M.E.L., (2020) Technology for Transformation is the Path Forward, Global Tapestry of Alternatives Newsletter, July. https://globaltapestryofalternatives.org/newsletters:01:index [5] Rossiter, N. and Zehle, S., (2018) Towards a Politics of Anonymity: Algorithmic Actors in the Constitution of Collective Agency and the Implications for Global Economic Justice Movements, in Parker et al (eds) The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, London: Routledge. [6] Zuboff, S., (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, London: Profile Books. [7] See Liu, W. (2020) Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology from Capitalism, London: Repeater Books. 4/10/2021 Jean Grave, the First World War, and the memorialisation of anarchism: An interview with Constance Bantman, part 2Read Now by John-Erik Hansson

John-Erik Hansson: Let us now talk about the French and European contexts and turn to the First World War and to the relationship between anarchism and the French Third Republic. You discuss at length Jean Grave’s u-turn regarding the war and what leads him to draft and sign the Manifesto of the Sixteen, condemning him to oblivion, because he was one of the apostates—although other signatories like Kropotkin managed to remain in the good graces of a lot of people in the anarchist movement. There's an ongoing revision of our understanding of what exactly led to the split in the anarchist movement between the defencists, who were in favour of participating in the war, and those who simply opposed the First World War, exemplified by the recent edited collection Anarchism 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War.[1] For a long time being defencism was considered to be a betrayal of anarchist principles, but that view has changed over the last couple of years. What was Grave’s role in this debate? How does studying Grave help us rethink anarchism at that historical juncture?

Constance Bantman: The first thing to say is that the revision is very much an academic thing; that’s important to highlight when you talk about anarchism, which is of course a social movement with a very strong historical culture. The war will come up when you're talking to the activists who really know their history when you mention Grave. On France’s leading anarchist radio channel, Radio Libertaire, a few years ago, I heard him called a “social traître” [traitor to the cause]—I couldn't believe it! But within academic circles, the revision is underway and a great deal has come out: the volume that you mentioned and Ruth Kinna’s work on Kropotkin as well, all of which have been very important to revising this history. That’s courageous work as well, given all we’ve said about the enduringly sensitive nature of this discussion. Concerning Grave’s role in this, the first aspect to consider is the importance of daily interactions in people's lives. That’s an angle you get from a biography. So much has been said about Kropotkin’s own story and intellectual positions, and how this informed his stance during the war. Of course, that doesn't explain everything, especially if you look to the opponents to the war. Grave was initially really opposed to the war, his transition was really gradual but it was a U-turn, connected to his friendship with Kropotkin, who told him off quite fiercely for being opposed to the war. One thing we do see through Grave is this sense that some anarchists clearly predicted what would later be known revanchisme, the idea that there was so much militarism in French society that when the Entente won the war, there would be really brutal terms imposed on Germany, which would lead to another war. That’s something that Peter Ryley has written about in Anarchism 1914-18. Some anarchists were pretty lucid actually in their analysis and you do found traces of that in Grave. He really clearly understood the depth of the militarism of French society, and that's when he did a bit of a U-turn. He was also in Britain at the time, and didn't quite realise how difficult the situation was. He had left Les Temps Nouveaux and the paper was looked after by colleagues. They were receiving lots of letters from the front, from soldiers and, as has been analysed by other historians, this was crucial in the growth of an anti-war sentiment for them. They could see directly the horrors happening in the trenches, whereas Grave was immersed in upper-class British circles and had no clear sense of the brutality of the war. So, again, it's a mixture of ideas, ideology, and the contingencies of personal and activist lives when you try to assess positions that such complicated times. JEH: Again, this highlights the importance of personal connections in the formulation of political and ideological positions. While these positions might be influenced by personal connections, they then become rationalised into arguments that become part of the ideological vocabulary and the ideological fault lines in the movement itself… and that leads to the Manifesto of the Sixteen, in a sense. CB: Yes, absolutely that's very true. The manifesto was written as a document published initially in the press; it was not a placard. Arguments in favour of defencism as well as arguments by anti-war groups were published in the press in the form of letters meant to influence people. Grave once referred to the Manifesto of the Sixteen as the manifesto he wrote in 1917, whereas it had actually been written in 1916. This just shows that what is now regarded as this landmark document, this watershed moment in the history of Western anarchism was, for Grave, just one of the many articles that he had written. I think it took some time, maybe a decade or two, you can see that through Grave, for the Manifesto to be consolidated into the historical monument that it now is. Looking at this period through Grave brings out a degree of fluidity which is otherwise not apparent. JEH: This is very interesting point. In a way, anarchists built their own historical narrative and created a landmark out of something that was, as you mentioned, initially just another set of arguments between people who are connected and often knew one another personally. But this particular argument became much more important because of the way in which the anarchist movement memorialised itself. CB: Yes, absolutely and I think tracing it would be interested to trace how national historiographies and activist memories sort of converge to establish versions of history. In France, I would be really interested to see when exactly the Manifesto of the Sixteen congealed into this historic landmark. I wonder if it's Maitron and a mixture of activist circles and discussions. I haven't studied so much the period around the Second World War, but really, with activist memories in this period we may have a missing link here to understand the formation and how the 19th century was memorialised. JEH: From the First World War to the Third Republic, I would like to relate your book to a recent article by Danny Evans.[2] Evans argues that anarchism could or should be seen as “the movement and imaginary that opposed the national integration of working classes”. Grave is interesting in this respect because he becomes domesticated by the Third Republic. Would you say that anarchism and French republicanism are in a kind of dialectical relationship from 1870 until the Second World War, moving from hard-hitting repression to the domestication of a certain strand of anarchism seen as respectable or acceptable by French republicanism? CB: Now that's a very good point, and an important contribution by Danny Evans. Grave always had these links with progressive Republican figures and organisations like the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, Freethinkers, academics etc.… One of his assets as well among his networks is his ability to get on with people, to mobilise them, for instance, in protest again repression in Spain and the Hispanic world. Many progressive figures were involved in that. And when Grave himself fell foul of the law during the highly repressive episode of 1892–94, many Republicans supported him, which suggests that a degree of republican integration was always latent for Grave. Then the war happened and he picked the right side from the Republicans’ perspective, and by then you're right, domestication is indeed a good term. I would also add that many of these Republicans considered that anarchism had been an important episode in the history of the young Third Republic, which might have made more favourably inclined towards it. Now if we look at domestication, Grave is an example of a sort of willing domestication, as you might say that perhaps he does age into conservative anarchism. But a classic example is that of Louise Michel. Sidonie Verhaeghe has just written a really interesting book about this[3], because if you think about Louise Michel having her entry into the Pantheon being discussed in recent years, she would be absolutely horrified at the suggestion. Having a square named after her at the foot of the Sacré Coeur, that’s almost trolling! But anarchism really reflects the history of the Third Republic from the early days, when the Republic was very unstable. You had the Boulangiste episode, and anarchism was perceived to be such a threat initially, until the strand represented by Grave ceases to be seen in that way. After the war, we enter the phase of memorialisation and reinterpretation; Michel and Grave represent two slightly different facets of that process. Regarding the point about the integration of the working classes, the flip side of Danny’s argument has often been used by historians—I'm thinking about Wayne Thorpe,[4] in particular—to explain why everything fell apart for French anarchists at the start of the First World War. The war just revealed how integrated the French working classes were, beyond the rhetoric of defiance they displayed. It's an argument you find to explain the lack of numerical strength of the CGT too. The working classes had integrated and the Republic had taken root, and Thorpe explains what happens with the First World War in the anarchist and syndicalist movements across Europe by looking at the prism of integration. That's a very fruitful way of looking at it. That's also great explanation because it encompasses so many different factors—economics, political control, and the rise of the big socialist parties which was of course crucial at the time. JEH: Actually, I was also thinking of the historical memory of socialists, as mass party socialism becomes dominant in the 20th century. In the late 19th century in the early 20th century when socialism was formulated, anarchism was an important part of that broad ideological conversation. But by the end of the First World War, from the socialists’ perspective, that debate is over. The socialists have won the ideological battle, and they are able to mobilise in a way that the anarchists aren't able to anymore. And at that point, the socialists can look back and try to bring anarchists into the fold, paying a form of respect to anarchism as an important part of socialist history. CB: Yes, I think there is probably an element of that, perhaps even an element of nostalgia. Many of these socialist leaders had dabbled with anarchism themselves before the war, so there is this dimension of personal experience and sometimes affinity. And it was still fairly recent history for them, I suppose, which plays out in a number of ways. There’s also the question of what happens with revolutionary ideas—for us the revolution is a fairly distant event, but for them the Commune was not such a distant memory. So, there is also this question of what do you do with a genuine revolutionary movement, like anarchism, and I think it was probably something they had to consider. [1] Ruth Kinna and Matthew S. Adams, eds., Anarchism, 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020); see also Matthew S. Adams, “Anarchism and the First World War,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, ed. Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_23. [2] https://abcwithdannyandjim.substack.com/p/anarchism-as-non-integration [3] Sidonie Verhaeghe, Vive Louise Michel! Célébrité et postérité d’une figure anarchiste (Vulaines sur Seine: Editions du Croquant, 2021). [4] Wayne Thorpe, “The European Syndicalists and the War, 1914-1918”, Contemporary European History 10(1) (2001), 1–24; J.-J. Becker and A. Kriegel, 1914: La Guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français (Paris: Armand Colin, 1964). 27/9/2021 Jean Grave, print culture, and the networks of anarchist transnationalism: An interview with Constance BantmanRead Now by John-Erik Hansson

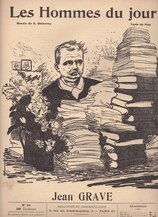

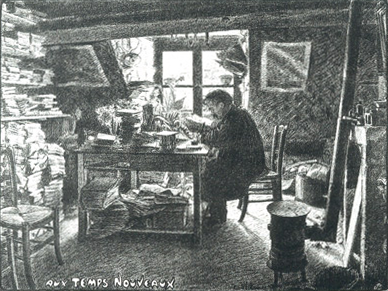

John-Erik Hansson: Let's start with a few introductory questions. Very broadly, who Jean Grave and why should we study him? What does he stand for? Does the book present a general case for studying minor figures in the history of anarchism, as Jean Grave is no longer necessarily so well known?