by Joanne Paul

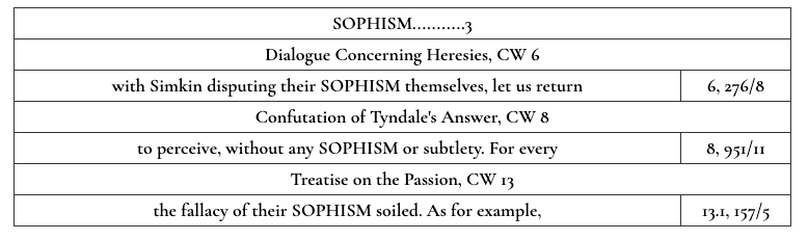

A lot can be said about the relationship between utopianism and ideology, and Gregory Claeys covered much of it in his comprehensive and detailed contribution to this blog.[1] As with all discussions of utopianism, however, participants cannot help but acknowledge the roots of the concept in the originator of the term, Thomas More’s masterfully enigmatic Utopia (full title: On the Best State of the Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia). Whether it was More himself who coined the term (it has been suggested it was in fact Erasmus), and acknowledging the longer (and global) history of imagined ideal states, any consideration of utopianism must at some point trace itself to More’s sixteenth-century text. This can make for some awkward anachronistic connections, especially for anyone concerned particularly with the importance of contextualism in the analysis of historic texts (as I am). Even the question of whether there is an ‘ideology’ present in More’s text can immediately be countered with the charge of anachronism. This is, of course, an issue with the term itself. However, much like we might acknowledge utopias (or utopian thinking) prior to 1516, we might also entertain the suggestion that ideology as a concept (if not a term) might have existed prior to the Enlightenment, and that various contemporary ideologies might also have their roots in the Renaissance, even if More would have been perplexed—but likely intrigued—by the term itself. The purpose of this piece, then, is to explore two interrelated questions. First, whether we can think about ideology and Utopia without giving ourselves entirely over to anachronism and thus a reading of the text that cannot be substantiated. Second, in a similar vein, to test the waters with a variety of ‘ideologies’ with which Utopia has been associated: republicanism, liberalism, totalitarianism/authoritarianism, socialism/communism, and, of course, utopianism. In this ‘testing’, the first criteria will be consistency within the text itself, but in establishing this, I will be reading the text in the context of More’s times and other works. Utopia is too frequently read as a stand-alone text despite—or perhaps because of—More’s substantial oeuvre. It is an intentionally ambiguous work, which is why so many different and even opposed ideologies can be read into it. In order to test the legitimacy of these readings, we must understanding Utopia in the context of More’s work more widely. A short caveat: none of this, of course, precludes the use of Utopia as an inspiration or foundation for a variety of ideological arguments, and Claeys has repeatedly made an impassioned and vitally important argument for the role of utopian thinking in meeting the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century (along with another contribution to this blog by Mathias Thaler)[2]. Political theorists and philosophers have—often very good—reasons for playing harder and faster with the ‘rules’ of historical contextualism (for more on this, see in particular the work of Adrian Blau).[3] There are, however, also good reasons to want to be attentive to the particularities of an utterance in its historical context, which I will not rehearse here, but which I hope are evident in what follows. Ideology and Utopia Does the idea of ‘ideology’ fit with a sixteenth-century intellectual mindset? More was not unfamiliar with the notion of ‘-isms’, often seen as the shorthand for identifying ideologies (though not in the explicitly modern sense).[4] Most of these ‘-isms’ were religious, not just less ‘ideological’ words like baptism, but those that more accurately fit the definition of a ‘system of beliefs’ such as ‘Judaism’, which More used in his Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer (1532).[5] It was the Reformation, Harro Höpfl has noted, which saw the widespread use of ‘isms’ to refer to ‘theological or religious positions considered heretical, and also to refer to the doctrines of various philosophical schools’.[6] Indeed More used the term ‘sophism’ (see the excerpt from the concordance above) in a way that arguably had ideological connotations, and not expressly or necessarily religious ones.[7] That being said, Ideology’s association with political ideas as wholly distinct from religious ones might have not squared with More’s worldview. Any religion can fit the definition of an ‘ideology’ and religious ideas permeated every aspect of More’s world, including—and especially—politics. The way in which Utopia can and has been read as an especially secular text is part of what makes it an enduringly popular text to study, certainly more than More’s other—obviously (and vehemently) religious—writings. There is something attractively secular about More’s pre-Christian island, which is based more obviously on classical pagan influences than medieval Christian ones. For this reason, it is temptingly easy to read a series of ideologies into this short book. The interesting question for a historian like myself becomes whether these were ideas available and attractive to More himself. Republicanism The island of Utopia is obviously and expressly a republic, and the neo-classical humanist More would have fully understood what this entailed. Both books of the text articulate, as Quentin Skinner has demonstrated, arguments for a Ciceronian vita activa, on which republicanism is based.[8] Although each Utopian city is ruled by a princeps, they are elected, and rule in consultation with an assembly of elected ‘tranibors’. The island as a whole is ruled by a General Council, made up of representatives elected from each city. This description of Utopia is framed by a discussion about the merits of the active life in the context of a monarchy, echoing similar discussions in Isocrates, Cicero, Erasmus, and others.[9] Does this align Utopia with ‘republicanism’ as an ideology? Certainly, the text deserves an important place in the development of that ideology from its ‘Athenian and Roman roots’, especially when read in the context of More’s other writings, which express a conciliarism that clearly has overlaps with classical republicanism. In his Latin Historia Richardi Tertii, More writes that parliament, which he calls a senatus, has ‘supreme and absolute’ authority, and in his religious polemics, he is keen to draw a connection between the parliament and the General Council.[10] The latter, he writes, has the power to depose the Pope and, whereas the Pope’s primacy can be held in doubt, ‘the general councils assembled lawfully… the authority thereof ought to be taken for undoubtable’.[11] Both parliament and the General Council are authorised representatives of the whole community, whether the church or the realm.[12] More also expresses ideas in line with what has come to be known as ‘republican liberty’: ‘non-domination’ or ‘that freedom within civil associations’, impling the lack of an ‘arbitrary power’ which would reduce ‘the status of free-man to that of slaves’.[13] In his justification of the importance of law, More writes, that ‘if you take away the laws and leave everything free to the magistrates… they will rule by the leading of their own nature… and then the people will be in no way freer, but, by reason of a condition of servitude, worse’.[14] This aligns with the Renaissance view of tyranny as ruling according to one’s own willful passions, rather than right reason. More certainly saw unfreedom in the rule of licentia (or license) over reason.[15] This could be found both in the rule of a single tyrant and in the anarchy of pluralism, a situation he feared would arise from Lutheranism.[16] As such, a firmly established structure of self-government, like that in Utopia, was the ideal way to ensure his notion of freedom, one that was largely in accordance with the republican tradition. Liberalism This is in contrast with notion of freedom advanced in Utopia by the character Raphael Hythloday, which we might think of as more in line with a ‘liberal’ perspective. He does not want to ‘enslave’ himself to a king and prefers to ‘live as I please’, certainly more ‘license’ than ‘liberty’ in More’s perspective.[17] There is an inherent contradiction between republican and liberal notions of liberty. In so far as More can be said to express something of the former, he is deeply against the latter. Individualism sits at the heart of liberalism; it is, as Michael Freeden and Marc Stears have suggested (though not without qualification), ‘an individualist creed’, seeking to enshrine ‘individual rights, social equality, and constraints on the interventions of social and political power’.[18] Liberalism was a product of the Enlightenment, and so More could not properly be said to be its opponent, but he did powerfully critique what we might see as its nascent constitute parts. In his other works, More often repeats a distinction between the people (populus) and ‘anyone whatever’ (quislibet), to the derision of the authority of the latter.[19] This lies at the heart of his fear of anarchy and Lutheranism, which he accuses of transferring ‘the authority of judging doctrines… from the people and deliver[ing] it to anyone whatever’.[20] In Utopia, we can see this critique of proto-individualism in his central message about pride, which he (with Augustine) takes to be the root of all sin, as it necessarily cuts across the bonds that should unite the populus. Pride is not just self-love, but self-elevation, a form of comparative arrogance that seeks to mark one out from others (a sin he associates with the scholastics, vice-ridden nobility, Lutherans, and indeed most of his opponents). Utopia has thus been read as a repressive regime which quashes—rather than upholds—freedom. This is from the perspective of post-Enlightenment liberalism, and takes Utopia perhaps more literally than it is meant. Read as a critique of the pride which we might associate with a sort of proto-individualism, it offers a powerful critique of an ideology which is—it must be acknowledged—in need of a reassessment. Totalitarianism/Authoritarianism It is for its anti-liberal qualities that Utopia has ended up associated with some of the darkest ideologies of the 20th century. More’s biographer, Richard Marius, called his views about education—certainly present in Utopia—‘an authoritarian concept, suitable for an authoritarian age’. Others have associated Utopia explicitly with totalitarianism.[21] Of the two, authoritarianism might be the more likely. There is a very clear desire in the setting out of the Utopian political and social system to have laws inculcated. The emphasis on what is referred to as ‘education’ or ‘training’ [institutis] might make 21st century readers think instead of socialisation or, more pessimistically, indoctrination. Priests, for example, are responsible for children’s education, and must ‘take the greatest pains from the very first to instil into children’s minds, while still tender and pliable, good opinions which are also useful for the preservation of the commonwealth.’[22] For this, not only are laws and institutions employed, but also public opinion. In a land where everything is public, nothing is private, and thus all is subject to public opinion: ‘being under the eyes of all, people are bound either to be performing the usual labor or to be enjoying their leisure in a fashion not without decency’.[23] This ‘universal behaviour’ is the secret to Utopia’s success. What I think More wanted to draw attention to in Utopia is the way in which this happens anyway, and to reorient the inculcation of values (or ‘opinions’) towards ‘truer’ or more ‘eternal’ (of course even ‘divine’) values. Utopians laugh at gems and precious metals because they associate them with fools and chamber pots. We value them because we associate them with the wealthy and powerful. The Utopians are ‘made’ to be dutiful citizens. As Book One suggests, ‘When you allow your youths to be badly brought up and their characters, even from early years, to become more and more corrupt, to be punished, of course, when, as grown-up men, they commit the crimes from boyhood they have shown every prospect of committing, what else, I ask, do you do but first create thieves and then become the very agents of their punishment?’.[24] In both cases, More suggests in Utopia and elsewhere, these values (or opinions) are built on a sort of ‘consensus’. The suggestion that this is authoritarian stems from a post-Enlightenment perspective that looks to see the liberal individual protected (as set out in part III above), of which More is many ways presenting a sort of ‘proto-critique’. While the republicanism of Utopia would, to some minds (and I would suspect to More’s), prevent it from being accurately labelled authoritarian—the citizenry is, after all, involved in its governance—to others this would not suffice. Would More have minded an ‘authoritarian’ society, if the values it inculcated with the ‘right’ ones? Perhaps not. More’s point, however, that we all submit to and are shaped by various sources of authority, and that the power to reorient the values cultivated by these authorities has been and continues to be a powerful one. Socialism/communism The early socialist thinkers were inspired by More to think that they might make people better through their organisation of society and its institutions (primarily education). In this historical context, we also have to contend, at least for a moment, with utilitarianism, and the Utopian’s ‘hedonism’ (or more properly Epicureanism). Jeremy Bentham, of course, held stock in the factory of utopian socialist Robert Owen. Helen Taylor (stepdaughter of J.S. Mill) wrote that in Utopia More ‘lays down a completely Utilitarian system of ethics’ as well as an ‘eloquently and yet closely reasoned defense of Socialism’. More was not an Epicurean (nor, of course, a utilitarian), though was interested to get back to more ‘real’ or ‘true’ pleasures over those false ones (we might think again of Utopians’ views of gems and precious metals). What I have called his republicanism might have also meant he was more interested in the good of the many over the few, though perhaps not quite in those terms (instead, the common good over any individual good). This emphasis on ‘common good’, of course, translates into ‘common goods’ in Utopia, where everything is held in common. This abolition of anything private (and thus private property) has led him to be read as a socialist and/or communist thinker, the latter not least by Marx and Engels. Beyond Utopia, however, More does make some very un-socialist comments. Through the central figure of Anthony in his Dialogue of Comfort (1534), More suggests in an Aristotelian vein that economic inequality is essential for the commonwealth; there must be ‘men of substance… for else more beggars shall you have’.[25] The golden hen must not be cut up for the few riches one might find inside. The larger point More wants to make in this text, however, is that even the richest do not ‘own’ their property. Property is a fiction and needs to be seen as such. Thus a rich man can keep his wealth so long as he recognises it is only his by the fictions of the society in which he lives, and ought (therefore) to be used to benefit the commonwealth. Wealth, position, and so on, More advocates, ‘by the good use thereof, to make them matter of our merit with God’s help in the life after.’ This is not a socialist nor a communist position, and it is certainly not materialist. More’s entire argument seeks to cultivate a conscious neglect of material realities in favour of the decidedly immaterial. Utopia, then, serves as a reminder of the immaterial realities underneath the social fictions generated in Europe (property, money, social hierarchy, etc). Living in that—shall we say—‘fictive reality’, however, means using those falsities towards the higher ends. As More’s friend John Colet put it: ‘use well temporal things. Desire eternal things.’ Utopianism Utopianism is at once an ideology, has characteristics similar to ideology, might encompass all ideologies, and is entirely opposed to it.[26] I will not rehearse the arguments of Sargent and Claeys here, but the three ‘faces’ that they speak of: utopian literature, utopian communities/practice, and utopian social theory are of course drawn from More’s 1516 text, and Sargent even suggests that ‘the meaning of [utopia] has not changed significantly from 1516 to the present’. So can we accept the obvious, then, that utopianism, as an ideology, is present in More’s text? Unfortunately, this question would seem to hinge on the fraught question of More’s sincerity in setting out the merits of the island of Utopia and the extent to which it is a community that he intended his readers to emulate. In many ways, our answer to this question has the power to overturn the very notion of any ideology being present in at least a surface reading of Utopia. If we were to conclude that Utopia is pure satire, and that the only arguments made in it are negative deconstructive ones, we would be hard-pressed to find any ideology within it at all.[27] I have made my own arguments about the central argument of Utopia, which I will not rehearse here, but the good news is that we can engage with the issue of utopianism in Utopia without answering this seemingly unanswerable question. Say what you will about the difficult question of More’s intentions, it would be difficult indeed to suggest that he was putting forward a blueprint of any kind for the construction of a practical community or endorsing the direct adoption of any of the practices exhibited in Utopia. The idea that Utopia exhibits—to use the words of Crane Brinton—‘a plan [that] must be developed and put into execution’ creates a sense of unease, to say the least. Afterall, More famously ends his text with the conclusion that ‘in the Utopian commonwealth there are very many features that in our own societies I would wish rather than expect to see’.[28] Despite the consensus that this passage is central to our understanding of Utopia, scholars have generally not attempted to read this statement in the context of More’s other works. When we do, we see that More applied this phrase elsewhere as well, and provided more of an explanation than he does in Utopia. In his Apology of 1533, More tells his reader that it would be wonderful if the world was filled with people who were ‘so good’ that there were no faults and no heresy needing punishment. Unfortunately, ‘this is more easy to wish, than likely to look for’.[29] Because of this reality, all one can do is ‘labour to make himself better’ and ‘charitably bear with others’ where he can. It is an internal reorganisation of priorities, drawn in large part from More’s reading of Augustine; what is common and shared must be prioritised over that which is one’s own. This, I have argued elsewhere, is what sits at the heart of More’s oeuvre, and we should be unsurprised to find it in Utopia as well. It is not the case, then, that More is advocating for what we might recognise as utopianism, but rather than Utopia is re-enforcing the arguments he makes elsewhere: the destructive power of pride and the personal need to prioritise the common over the individual. Conclusion: Moreanism? Does this mean, at last, we have come to an ideology in Utopia? A sort of republicanism-light, a proto-communitarianism, an anti-liberalism? I leave it to political theorists to hash out what More’s view might be termed—or indeed if a label is useful at all. Utopia can, indeed, be read in a variety of ways, which support a diversity of ideological positions. It becomes more difficult, I think, to read these positions into More’s thought as a whole. When we examine his corpus, we see a preoccupation with the common good, expressed through representative quasi-republican institutions, and the eternal/immaterial, but also a pragmatism (even ‘realism’?) about the artificialities of the world in which we live. It is the work of a much larger piece to flesh this out in whole, and this small article has instead focused largely on what More cannot be said to be. Hopefully, however, this is in itself a utopian exercise. In understanding Not-More, we might better understand More himself. [1] ‘Utopianism as a Political Ideology: An Attempt at Redefinition’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/04/utopianism-as-a-political-ideology-an-attempt-at-redefinition.html. [2] ‘“We Are Going to Have to Imagine Our Way out of This!”: Utopian Thinking and Acting in the Climate Emergency’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/09/we-are-going-to-have-to-imagine-our-way-out-of-this-utopian-thinking-and-acting-in-the-climate-emergency.html. [3] Adrian Blau, ‘Interpreting Texts’, in Methods in Analytical Political Theory, ed. Adrian Blau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 243–69, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316162576.013. [4] H. M. Höpfl, ‘Isms’, British Journal of Political Science 13, no. 1 (January 1983): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003112. [5] Thomas More, The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More: The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, ed. Louis A. Schuster, Richard C. Marius, and James P. Lusardi, vol. 8 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), 782. [6] Höpfl , ‘Isms’, 1; most of these do not appear in More’s work, though ‘papist’ does (24 times), which is a derivation of ‘papism’; likewise ‘donatists’ (26 times) from ‘donatism’ see https://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance/. Of course, this discussion is of English ‘isms’, and Utopia, along with a handful of More’s other writing, is Latin. Ism itself is a Latin (from Greek, and into French) derivation, for the suffix ‘-ismus’ (masculine). However, text-searches and concordances did not turn up many of these either, nor do ‘isms’ appear in the text of translations consulted. [7] ‘Concordances’, Thomas More Studies (blog), accessed 8 February 2022, http://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance-home/. [8] Quentin Skinner, ‘Thomas More’s Utopia and the Virtue of True Nobility’, in Visions of Politics: Volume 2: Renaissance Virtues (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 213–44. [9] Joanne Paul, Counsel and Command in Early Modern English Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), chapter 1. [10] More, Letters, 321. In the Confutation, 287 he justifies this approach, suggesting that ‘senatus Londinensis’ could be translated ‘as mayor, aldermen, and common council’. [11] More, Letters, 213. [12] More, Confutation, 146, 937. [13] Quentin Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), ix-x. This is not inconsistent with the fact that free-men could indeed become slaves in Utopia. In fact, the presence of slaves only highlights the emphasis on the sort of freedom enjoyed by law-abiding Utopian citizens.[13] Slaves are drawn from either within Utopia - those condemned of ‘some heinous offence’ - or without – captured prisoners of war, those who have been condemned to death in their own country or, thirdly, those who volunteer for it as a preferable option to poverty elsewhere.[13] Notably, in none of these cases is slavery hereditary and slaves cannot be purchased from abroad; Thomas More, More: Utopia, ed. George M. Logan and Robert M. Adams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 77. [14] More, Responsio Ad Lutherum, 277. All references to More’s works taken from the Yale Collected Works series, unless otherwise indicated. [15] Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty, 30-1. [16] Joanne Paul, Thomas More (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 98-9. [17] More, Utopia, 13. [18] Michael Freeden and Marc Stears, ‘Liberalism’, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [19] Paul, Thomas More, 99. [20] More, Responsio, 613. [21] Richard Marius, Thomas More: a biography (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 199), p. 235; Wolfgang E. H. Rudat, ‘Thomas More and Hythloday: Some Speculations on Utopia’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 43, no. 1 (1981): 123–27; J. C. Davis, Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Hanan Yoran, Between Utopia and Dystopia: Erasmus, Thomas More, and the Humanist Republic of Letters (Lexington Books, 2010), 13, 167, 174, 182-3. [22] More, Utopia, 229. [23] More, Utopia, 46. [24] More, Utopia, 71. [25] More, Dialogue of Comfort, 179. [26] Lyman Tower Sargent, ‘Ideology and Utopia’ in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [27] This leads me to address the Erasmus-shaped elephant in the room: what about humanism? Even if Utopia is entirely critical, then the ‘ism’ that might be left standing would be humanism. It’s important to note, however, that humanism has been rather unfortunately named, as scholars agree that it is most definitely not a defined or coherent system of beliefs, but rather a curriculum of learning, an approach to the study of texts and at most a series of questions to which ‘humanists’ provided a variety of answers. One of those question does indeed address the best state of the commonwealth, to which Utopia is a – thoroughly enigmatic – answer. [28] ‘in Utopiensium republica, quae in nostris civitatibus optarim verius, quam sperarim.’ [29] More, Apology, 166. by Daniel Davison-Vecchione

Social theorists are increasingly showing interest in the speculative—in the application of the imagination to the future. This hearkens back to H. G. Wells’ view that “the creation of Utopias—and their exhaustive criticism—is the proper and distinctive method of sociology”.[1] Like Wells, recent sociological thinkers believe that the kind of imagination on display in speculative literature valuably contributes to understanding and thinking critically about society. Ruth Levitas explicitly advocates a utopian approach to sociology: a provisional, reflexive, and dialogic method for exploring alternative possible futures that she terms the Imaginary Reconstitution of Society.[2] Similarly, Matt Dawson points to how social theorists like Émile Durkheim have long used the tools of sociology to critique and offer alternative visions of society.[3]

As these examples illustrate, this renewed social-theoretical interest in the speculative tends much more towards utopia than dystopia.[4] Unfortunately, this has meant an almost complete neglect of how dystopia can contribute to understanding and thinking critically about society. This neglect partly stems from how under-theorised dystopia is compared to utopia. Here I make the case for considering dystopia and social theory alongside each other.[5] In short, doing so helps illuminate (i) the kind of theorising about society that dystopian authors implicitly engage in and (ii) the kind of imagination implicitly at work in many classic texts of social theory. The characteristics and politics of dystopia A simple, initial definition of a dystopia might be an imaginative portrayal of a (very) bad place, as opposed to a utopia, which is an imaginative portrayal of a (very) good place. In Kingsley Amis’ oft-quoted words, dystopias draw “new maps of hell”.[6] Many leading theorists, including Krishan Kumar and Fredric Jameson, tend to conflate dystopia with anti-utopia.[7] It is true that numerous dystopias, such as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940), concern the horrifying consequences of attempted utopian schemes. However, not all dystopias are straightforwardly classifiable as anti-utopias. Take Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). The leaders of the patriarchal, theocratic Republic of Gilead present their regime as a utopia, which one might consider a kind of counter-utopia to what they see as the naïve and materialistic ideals of contemporary America, and at least some of these leaders sincerely believe in the set of values that the regime realises in part. One might therefore conclude that the novel is a warning that utopian thinking inevitably leads to and justifies oppressive practices. However, I would argue that The Handmaid’s Tale is not a critique of utopia as such, but rather of how actors with vested interests frame the actualisation of their ideologies as the attainment of utopia to discourage critical thinking. This reading is supported by how, for many members of Gilead’s ruling elite, the presentation of their society as a utopia is little more than self-serving rhetoric they use to brainwash the women they subjugate. Other dystopian works contain anti-utopian elements but subordinate these to the exploration of other themes. For instance, a subplot of Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan (2017) concerns a celebrity-turned-dictator’s dream of a technologically “improved” humanity, but resource wars, global warming, and other factors had already made the novel’s setting decidedly dystopian before this utopian scheme arose. Finally, there are major examples of dystopian literature, such as Octavia Butler’s Parable series (1993–1998), that depart from the anti-utopian template altogether. Tom Moylan has begun to rectify the dystopia/anti-utopia conflation via the concept of the critical dystopia. In his words, critical-dystopian texts “linger in the terrors of the present even as they exemplify what is needed to transform it”.[8] Put simply, critical dystopias are dystopias that retain a utopian impulse. Although this helps us understand many significant dystopian works, such as Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Gold Coast (1988) and Marge Piercey’s He, She and It (1991), the idea of the critical dystopia runs into its own problems. By labelling as “critical” only those dystopias that retain a utopian impulse, one makes it seem as if dystopia does not help us to understand and evaluate society in its own right—dystopia’s critical import becomes, so to speak, parasitic on utopia. To illustrate how this sells dystopia short, consider the extrapolative dystopia; that is, the kind of dystopia that identifies a current trend or process in society and then imaginatively extrapolates “to some conceivable, though not inevitable, future state of affairs”.[9] Many of Atwood’s novels fall into this subcategory. In her own words, The Year of the Flood (2009) is “fiction, but the general tendencies and many of the details in it are alarmingly close to fact”, and MaddAddam (2013) “does not include any technologies or biobeings that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory”.[10] These texts, which together with Oryx & Crake (2003) form Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, consider possible, wide-reaching changes that are rooted in present-day social and technological developments and raise pressing questions as to environmental degradation, reproduction and fertility, and the boundaries of humanity. Similarly, Butler constructs the dystopian future in her Parable series by extrapolating from familiar tendencies within American society, including racism, neoliberal capitalism, and religious fundamentalism. My point is not simply that these extrapolative dystopias are cautionary tales. It is that one cannot reduce their critical effect to either the negation or the retention of a utopian impulse. They identify certain empirically observable tendencies that have serious socio-political implications in the present and are liable to worsen over time. As such, they are critiques of present-day social phenomena and (more or less) plausible projections of how a given society might develop. The implicit message is that we can avoid the bad future in question through intervention in the present. This is how dystopia can translate into real-world political action. Taking perhaps the most famous twentieth century dystopia, in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) George Orwell was not simply satirising Stalin’s USSR or Hitler’s Germany. He was also considering the nature and prospects of the worldwide developments he associated with totalitarianism, including centralised but undemocratic economies that establish caste systems, “emotional nihilism”, and a total skepticism towards objective truth “because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuehrer”.[11] In Orwell’s words, “That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible”.[12] In the last couple of decades, dystopian texts have frequently sought to make similar points about global warming, digital surveillance, and the “new authoritarianisms”. One can certainly argue that taking dystopia too seriously as a means of critically understanding society risks sliding into a catastrophist outlook that emphasises averting worse outcomes rather than producing better ones. However, one should bear in mind that dystopia does not (and should not) aim to provide a comprehensive political program; rather, it provides a speculative frame one can use to consider current developments, thereby yielding intellectual resources for envisaging positive alternatives. The social theory in dystopia and the dystopia in social theory This brings us to the more direct affinities between dystopia and social theory. To begin with, protagonists in dystopian texts like Orwell’s Winston Smith, Atwood’s Offred, and Butler’s Lauren Olamina tend to be much more reflective and three-dimensional than their classical utopian counterparts. This is because, unlike the “tourist” style of narration common to utopias, dystopias tend to be narrated from the perspective of an inhabitant of the imagined society; someone whose subjectivity has been shaped by that society’s historical conditions, structural arrangements, and forms of life.[13] As Sean Seeger and I have argued, this makes dystopia a potent exercise in what the American sociologist C. Wright Mills termed “the sociological imagination”; that is, the quality of mind that “enables us to grasp [social] history and [personal] biography and the relations between the two”, thereby allowing us to see the intersection between “the personal troubles of milieu” and “the public issues of social structure”.[14] Since dystopian world-building takes seriously (i) how a future society might historically arise from existing, empirically observable tendencies, (ii) how that society might “hang together” in terms of its political, cultural, and economic arrangements, and (iii) how these historical and structural contexts might shape the inner lives and personal experiences of that society’s inhabitants, one can say that such world-building implicitly engages in social theorising. Conversely, the empirically observable tendencies from which dystopias commonly extrapolate, and the ethical, political, and anthropological-characterological questions dystopias frequently pose, are central to many classic texts of social theory. For instance, Max Weber saw his intellectual project as a cultural science concerned with “the fate of our times”.[15] He extrapolated from such related macrosocial tendencies as rationalisation and bureaucratisation to envisage modern humanity encased and constituted by a “shell as hard as steel” (“stahlhartes Gehäuse”) and feared that “no summer bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness”.[16] This would already place Weber’s social theory close to dystopia, but the resemblance becomes uncanny when one also considers Weber’s central interest in “the economic and social conditions of existence [Daseinsbendingungen]” that shape “the quality of human beings” and his related emphasis on the need to preserve human excellence and to avoid giving way to mere “satisfaction”.[17] This is a dystopian theme par excellence, as seen from such classics in the genre as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1951), which gives additional significance to the famous, Nietzsche-inspired moment at the end of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905). Here Weber wonders who might “live in that shell in the future”, including the ossified and self-important “last men”; those “specialists without spirit, hedonists without a heart” who “imagine they have attained a stage of humankind [Menschentum] never before reached”.[18] Like a good extrapolative-dystopian author, Weber provides a conceptually rich account of social phenomena by reflecting on what is currently happening and speculating about its further development and implications. It therefore seems that the dystopian imagination has always been at play within the sociological canon. While the extent of the overlap between dystopia and social theory is yet to be fully determined, much of this overlap no doubt stems from how central social subjectivity is to both endeavours. It is true that, in their representations of societies, dystopian authors as writers of fiction are not subject to the same demands of accuracy as social theorists. Nevertheless, the critical effect of much dystopian literature relies heavily on empirical connections with the world inhabited by the reader and, conversely, social theory often evaluates by speculating about the possible consequences of current tendencies. As such, one cannot consistently maintain a straightforward separation between the two enterprises. I am therefore confident that this nascent, interdisciplinary area of study will be productive and insightful for both social scientists and scholars of speculative literature. My thanks to Jade Hinchliffe, Sean Seeger, Sacha Marten, and Richard Elliott for their helpful comments on an early draft of this essay. [1] H. G. Wells, “The So-Called Science of Sociology,” Sociological Papers 3 (1907): 357–369, 167. [2] Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [3] Matt Dawson, Social Theory for Alternative Societies (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016). [4] Zygmunt Bauman is a partial exception. See Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity, 2000 [1989]), 137; Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity, 2000), 26, 53–64; Zygmunt Bauman, Retrotopia (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), 1–12. [5] This essay raises and builds on points Sean Seeger and I have made in our ongoing collaborative research on speculative literature and social theory. See Sean Seeger and Daniel Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” Thesis Eleven 155, no. 1 (2019): 45-63. [6] Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1960). [7] Krishan Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times (London: Blackwell, 1987), viii; Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future (London: Verso, 2005), 198. [8] Tom Moylan, Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia (New York: Routledge), 198-199. [9] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 55. [10] Quoted in Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 482. [11] Quoted in Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times, 292-93. [12] Ibid. [13] This is complicated by the “critical utopias” that arose in the 1960s and 70s, which emphasise subjects and political agency much more than their classical antecedents. [14] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 50; C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000 [1959]), 6, 8. [15] See, e.g., Lawrence A. Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage: Culture, Politics, and Modernity in the Thought of Max Weber (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1991); Wilhelm Hennis, Max Weber’s Central Question (Newbury: Threshold Press, 2000). [16] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trs. Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 121; Max Weber, “Politics as a Vocation,” in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, eds. H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005) 77-128, 128. “Iron cage” is Talcott Parsons’ mistranslation of “stahlhartes Gehäuse”. [17] Max Weber, “The National State and Economic Policy” (1895), quoted in Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage, 30. [18] Weber, Protestant Ethic, 121. 13/9/2021 'We are going to have to imagine our way out of this!': Utopian thinking and acting in the climate emergencyRead Now by Mathias Thaler

In the public debate, the climate emergency has broadly given rise to two opposing reactions: either resignation, grief, and depression in the face of the Anthropocene’s most devastating impacts[1]; or a self-assured, hubristic faith in the miraculous capacity of science and technology to save our species from itself.[2]

But, as Donna Haraway forcefully asserts, neither of these reactions, relatable as they are, will get us very far.[3] What is called for instead is a sober reckoning with the existential obstacles lying ahead; a reckoning that still leaves space for the “educated hope”[4] that our planetary future is not yet foreordained. To accomplish these twin goals, utopian thinking and acting are paramount.[5] What could be the place of utopias in dealing with the climate emergency? To answer this question, we first have to clear up a widespread misunderstanding about the basic purpose of utopianism. Many will suspect that the utopian imagination appears, in fact, uniquely unsuited for illuminating the perplexing realities of a climate-changed world. On this view, utopianism amounts to the kind of escapism we urgently need to eschew, if we are serious about facing up to the momentous challenges the present has in store for us. Indulging in blue-sky thinking when the planet is literally on fire might be seen as the ultimate sign of our species’ pathological predilection for self-delusion. The charge that utopias construct alluring alternatives in great detail, without, however, explaining how we might get there, possesses an impressive pedigree in the history of ideas. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels excoriated the so-called utopian socialists for being supremely naïve when they paid scant attention to the role that the revolutionary subject—the proletariat—would have to play in forcing the transition to communism.[6] It is important to remark that the authors of the Communist Manifesto did not take issue with the glorious ideal that the utopian socialists venerated, quite to the contrary. Their concern was rather that focusing on the wished-for end point in history alone would be deleterious from the point of view of a truly radical politics, for we should not merely conjure what social form might replace the current order, but outline the concrete steps that need to be taken to transform the untenable status quo of capitalism. Marx and Engels were, to some degree, right. There are many types of utopian vision that serve nothing but consolation, trying to render an agonising situation more bearable by magically transporting the readers into a wonderous, bright future. These utopias typically present us with perfect and static images of what is to come. As such, they leave not only the pivotal issue of transition untouched, they also restrict the freedom of those summoned to imaginatively dwell in this brave new world—an objection levelled against utopianism by liberals of various stripes, from Karl Popper to Raymond Aron and Judith Shklar.[7] Yet, not all utopias fail to reflect on what ought to be practically done to overcome the existential obstacles of the current moment. Non-perfectionist utopias are apprehensive about both the promise and the peril of social dreaming.[8] In the words of the late French philosopher Miguel Abensour, their goal consists in educating our desire for other ways of being and living.[9] This wide framing allows for the observation of a great variety of utopias within and across three dimensions of thinking and acting: theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, as paradigmatically enacted in intentional communities.[10] The interpretive shortcut that critics of utopianism take is that they conceive of this education purely in terms of conjuring perfect and static images of other worlds. However, utopianism’s pedagogical interventions can follow different routes as well.[11] From the 1970s onwards, science fiction writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Marge Piercy and Octavia Butler started to build into their visions of the future modes of critically interrogating the collective wish to become otherwise.[12] Doubt and conflict are ubiquitous in their complex narratives. Social dreaming of this type turns out to be the opposite of escapism: as a self-reflective endeavour, it remains part and parcel of any radical politics worth its salt.[13] The education of our desire for alternative ways of being and living amounts to an intrinsically uncertain enterprise, always at risk of going awry, of collapsing into totalitarian oppression. There is, hence, no getting away from the fact that utopias can have problematic effects. But this does not mean we should jettison them altogether. The risks of not engaging in social dreaming far outweigh its obvious benefits: any attempt to cling to business as usual, at this moment of utmost emergency, will surely trigger an ever more catastrophic breakdown of the planetary condition, as the latest IPCC draft report into various climate scenarios unambiguously establishes. The path forward, then, entails acknowledging the eminent dangers in all efforts to conjure alternatives; dangers that can be negotiated and accommodated via theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, but never fully eliminated. This insight is aptly expressed in Kim Stanley Robinson’s work: "Must redefine utopia. It isn’t the perfect end-product of our wishes, define it so and it deserves the scorn of those who sneer when they hear the word. No. Utopia is the process of making a better world, the name for one path history can take, a dynamic, tumultuous, agonising process, with no end. Struggle forever."[14] If we recast utopianism along Robinson’s lines, what might be its lessons for navigating our climate-changed world? To answer this question, I propose we distinguish between three mechanisms that utopias deploy: estranging, galvanising, and cautioning. All utopias aim to exercise their critique of the status quo by doing one or several of these things. This can be illustrated through a quick glance at recent instances of theory-building and storytelling that grapple directly with our climate-changed world. Let us commence with estranging. When utopias make the extraordinary look ordinary, they seek to unsettle the audience’s common sense and therefore open up possibilities for transformation. One way of interpreting Bruno Latour’s recent appropriation of the Gaia figure is, accordingly, to decipher it as a utopian vision that hopes to disabuse its readers of anthropocentric views of the planet.[15] While James Lovelock initially came up with the idea to envisage Earth in terms of a self-regulating system, baptising the entirety of feedback loops of which the planet is composed with the mythological name “Gaia”, Latour attempts to vindicate a political ecology that repudiates the binary opposition of nature and culture, which obstructs a responsible engagement with environmental issues. From this, a deliberately strange image of Earth emerges, wherein agency is radically dispersed across multiple forms of being.[16] In N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, to refer to an interesting case of politically generative fantasy, our home planet is depicted as a vindictive agent that wages permanent war on its human occupants.[17] The upshot of this portrayal of the planetary habitat as a living, raging being, rather than a passive, calm background to humanity’s sovereign actions, is that the readers’ expectations of their natural surroundings are held in abeyance. Jemisin’s work captures Earth and its inhabitants through powerful allegories of universal connectedness—neatly termed “planetary weirding”[18]. What is more, the Broken Earth trilogy also sheds light on the shifting intersections of class, gender, racial, and environmental harms.[19] Hence, narratives such as this unfold plotlines that produce estrangement: they come up with imagined scenarios, which defamiliarise us from what we habitually take for granted.[20] Galvanising stories casts utopian visions in a slightly different light. These narratives describe alternatives whose purpose resides in revealing optimistic perspectives about the future. In contemporary environmentalist discourse, ecomodernists enlist this kind of emplotment strategy, most notably through their provocative belief that science and technology might eventually expedite a “decoupling” of human needs from natural resource systems.[21] Kim Stanley Robinson’s Science in the Capital trilogy inspects this alluring proposition with inimitable insight.[22] In his account of how the American scientific community might marshal its expertise to redirect the entire Washington apparatus onto a sustainable policy platform, Robinson attempts to establish that viable paths out of the current impasse do already exist—if only all the actors involved finally recognised the severity of the situation. The chief ambition behind this utopian frame is thus to affectively galvanise an audience that is at the moment either apathetic about its capacity to transform the status quo or paralyzed by the many hurdles that lie ahead. Finally, cautionary tales follow a plotline that is predicated on a bleaker judgment: unless we change our settled ways of being and living, the apocalypse will not be averted. Dystopian stories pursue this instruction by excavating hazardous trends that remain concealed within the current moment. Commentators such as Roy Scranton[23] or David Wallace-Wells[24] maintain that there is little we can do to slow down the planetary breakdown and the eventual demise of our own species. Margaret Atwood’s dystopian MaddAddam trilogy takes one step further when she prompts the reader to imagine how life after the cataclysmic collapse of human civilisation might look like.[25] The main task of this sort of narrative is to warn an audience about risks that are already present right now, but whose scale has not yet been fully appreciated in the wider public.[26] These three compressed cases show that the utopian imagination has much to add to the public debate around climate change; a debate that is about so much more than just plausible theories or appealing stories. Conjuring alternatives is as much about the modelling of other ways of being and living as it is about spurring resistant action. Social dreaming does not only involve abstract thought experiments; it also prompts a restructuring of human behaviour and as such proves to be deeply practical.[27] The climate emergency has, among many terrible outcomes, triggered a profound crisis of the imagination and action.[28] In this context, and despite legitimate worries about the deleterious aspects of social dreaming, we cannot afford to discard the estranging, galvanising, and cautioning impact that utopias generate. As one of the protagonists of the Science in the Capital trilogy declares: “We’re going to have to imagine our way out of this one.”[29] Acknowledgments With many thanks to Richard Elliott for the invitation to write this piece as well as for useful comments; and to Mihaela Mihai for productive feedback on an earlier draft. The research for this text has benefitted from a Research Fellowship by the Leverhulme Trust (RF-2020-445) and draws on work from my forthcoming book No Other Planet: Utopian Visions for a Climate-Changed World (Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022). [1] For a useful compendium of resources on the rise of (negative) emotions during the current climate crisis, see: https://www.bbc.com/future/columns/climate-emotions [2] The best example of this attitude can probably be found in Bill Gates’ recent endorsement of such solutionism. See: How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021). [3] Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). [4] Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope: Volume 1, trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight, Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 7, 9. [5] For a groundbreaking study, see: Lisa Garforth, Green Utopias: Environmental Hope before and after Nature (Cambridge: Polity, 2018). [6] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The Communist Manifesto,” in Selected Writings, by Karl Marx, ed. David McLellan, 2nd ed. (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 245–71. [7] On the anti-utopianism of these so-called “Cold War liberals”, see: Richard Shorten, Modernism and Totalitarianism: Rethinking the Intellectual Sources of Nazism and Stalinism, 1945 to the Present (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 109–49. [8] Lucy Sargisson, Fool’s Gold? Utopianism in the Twenty-First Century (Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). [9] Miguel Abensour, “William Morris: The Politics of Romance,” in Revolutionary Romanticism: A Drunken Boat Anthology, ed. Max Blechman (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1999), 126–61. [10] Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” Utopian Studies 5, no. 1 (1994): 1–37. [11] Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia, Student Edition (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2011); Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstruction of Society (Houndmills/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [12] On Le Guin and especially her masterpiece The Dispossessed, see: Tony Burns, Political Theory, Science Fiction, and Utopian Literature: Ursula K. Le Guin and the Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008); Laurence Davis and Peter Stillman, eds., The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2005). [13] Tom Moylan, Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination, ed. Raffaella Baccolini, Classics Edition (1986; repr., Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014). [14] Kim Stanley Robinson, Pacific Edge, Three Californias Triptych 3 (New York: Orb, 1995), para. 8.10. [15] Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, E-book (Cambridge/Medford: Polity, 2017). [16] See also: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010). [17] The Fifth Season, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 1 (New York: Orbit, 2015); The Obelisk Gate, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 2 (New York: Orbit, 2016); The Stone Sky, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 3 (New York: Orbit, 2017). [18] Moritz Ingwersen, “Geological Insurrections: Politics of Planetary Weirding from China Miéville to N. K. Jemisin,” in Spaces and Fictions of the Weird and the Fantastic: Ecologies, Geographies, Oddities, ed. Julius Greve and Florian Zappe, Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 73–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28116-8_6. [19] Alastair Iles, “Repairing the Broken Earth: N. K. Jemisin on Race and Environment in Transitions,” Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 7, no. 1 (July 11, 2019): 26, https://doi.org/10/ghf4k5; Fenne Bastiaansen, “The Entanglement of Climate Change, Capitalism and Oppression in The Broken Earth Trilogy by N. K. Jemisin” (MA Thesis, Utrecht, Utrecht University, 2020), https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/399139. [20] Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: Studies in the Poetics and History of Cognitive Estrangement in Fiction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978). [21] John Asafu-Adjaye, et al., “An Ecomodernist Manifesto,” 2015, http://www.ecomodernism.org/; See also: Manuel Arias-Maldonado, “Blooming Landscapes? The Paradox of Utopian Thinking in the Anthropocene,” Environmental Politics 29, no. 6 (2020): 1024–41, https://doi.org/10/ggk4vj; Jonathan Symons, Ecomodernism: Technology, Politics and the Climate Crisis (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019). [22] Forty Signs of Rain, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 1 (New York: Bantham, 2004); Fifty Degrees Below, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 2 (New York: Bantham, 2005); Sixty Days and Counting, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 3 (New York: Bantham, 2007). [23] Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization, E-book (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015). [24] The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming, E-book (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019). [25] Oryx and Crake, E-book, vol. 1: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2003); The Year of the Flood, E-book, vol. 2: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2009); MaddAddam, E-book, vol. 3: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2013). [26] Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History: A Study of Modern Despotism, Its Antecedents, and Its Literary Diffractions, First edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). [27] In the 1970s, the Swiss sociologist Alfred Willener coined the term “imaginaction” to capture what is distinct about action facilitated through imagination and imagination stirred by action. See: Alfred Willener, The Action-Image of Society: On Cultural Politicization (London: Tavistock Publications, 1970). [28] Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, E-book (London: Penguin, 2016), para. 9.2. [29] Robinson, Sixty Days and Counting, para. 58.11. by Eileen M. Hunt

Mary Shelley is most famous for writing the original monster story of the modern horror genre, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). She was also the author of the pandemic novel that unleashed the dominant tropes of post-apocalyptic literature upon modern political science fiction. Her fourth completed novel, The Last Man (1826), pictured the near annihilation of the human species by an unprecedented and highly pathogenic plague that surfaces during a war between Greece and Turkey in the year 2092. Shelley’s dystopian worlds, in turn, have inspired Marxist social and political theorists in their Promethean critiques of capitalism. Both Frankenstein’s monster and Shelley’s monster pandemic resonate with us during the time of Covid-19 because of the power and prescience of her iconic critiques of human-made disasters.

While she lived in Italy with her husband Percy, Shelley helped him translate and transcribe Plato’s Symposium, which contains the etymological origin of the English word “pandemic” (in ancient Greek, πάνδημος).[1] In Plato’s philosophical dialogue on the meaning of love, the goddess “Pandemos” is the “earthly Aphrodite” who oversees the bodily loves of “all” (pan) “people” (demos), men and women alike.[2] In the aftermath of the 1642-51 English Civil Wars and the 1665–66 Great Plague of London, the adjective “pandemic” gained salience in both political and medical contexts in seventeenth-century English. It could refer to either the disorders of democratic government by all people (as in monarchist John Rogers’s 1659 condemnation of the “unjust Equality of Pandemick Government”), or the visitation of pestilence to undermine the stability of the entire body politic (as in doctor Gideon Harvey’s 1666 description of “Endemick or Pandemick” diseases that “haunt a Country”).[3] According to this conceptual genealogy sketched by literary theorist Justin Clemens, two important homophonic variants of “Pandemick” emerged in the aftermath of the English Civil Wars. Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) defined “Panique Terror” as a contagious “passion” of fear that happens to “none but in a throng, or a multitude of people.”[4] Then John Milton invented the word “pandaemonium” for his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) to depict Satan’s hell as a kingdom where all the little devils lived in sin-infected chaos.[5] Indebted to her deep reading of Plato, Hobbes, and Milton, Shelley’s The Last Man conceived the global plague as an “epidemic” that affects or touches upon (epi) all (pan) people (demos) precisely because it stems from the disruptions of collective human corruption, panic, and politics.[6] In her first novel, Shelley had metaphorically rendered the revenge of Frankenstein’s “monster” upon his uncaring scientist-maker as an unstoppable “curse,” “scourge,” and “pest” upon their family and potentially “the whole human race.”[7] This unnamed “creature” was nothing less than a “catastrophe,” brought to life by the chemist Victor Frankenstein from an artificial assemblage of the dead parts of human and nonhuman animals.[8] His dark motivation for using his knowledge of chemistry, anatomy, and electricity to bring the dead back to life was the sudden loss of his mother to scarlet fever while she cared for his sick sister, cousin, and bride-to-be, Elizabeth. In her second great work of “political science fiction,” Shelley found new horror in reversing the direction of the metaphor.[9] No longer was the monster a plague: the plague itself was the monster. Shelley not only wrote the origin story for modern sf with Frankenstein. She also laid down the ur-text for modern post-apocalyptic fiction in The Last Man. With her great pandemic novel, Shelley panned out to see all plagues as human-made monstrosities that leave “a scene of havoc and death” behind them.[10] What made plagues so ghastly was their exponential power to multiply—causing a concatenation of disasters for their human authors, other afflicted people, and their wider environments on “a scale of fearful magnitude.”[11] In The Last Man, Shelley conceived all plagues—real and metaphorical—as human contaminations of wider environments. Bad human behaviors corroded the people closest to them, then spread like toxins through the cultural atmosphere to destroy the health and happiness of others. The ancient plagues of erotic and familial conflict, war, poverty, and pestilence had reproduced together and persisted into modernity through centuries of modelling, imitation, and replication of humanity’s worst behaviors in culture, society, and politics. Midway through The Last Man, the Greek princess Evadne issues an apocalyptic prophecy: humanity would soon be incinerated in a vortex of war, passion, and betrayal.[12] As she dies of “crimson fever” on a pestilential battlefield, she curses her beloved and the leader of the Greek forces Lord Raymond for abandoning her for his wife Perdita. “Fire, war, and plague,” she cries, “unite for thy destruction!”[13] As if on cue, the seasonal “visitation” of “PLAGUE” in Constantinople escalates into an international pandemic. With her uncanny insight into the social genesis of epidemics and other plagues upon humanity, Shelley—through the voice of Evadne—anticipated the economic and political theory of pandemics that has gained currency in the twenty-first-century. Back in 2005, the Marxist historian Mike Davis warned the world that zoonotic viral pandemics like the avian flu and SARS-CoV—whose genetically mutated strains enabled them to leap from nonhuman animals to a mass of human victims—were The Monster at Our Door.[14] While Davis did not cite Shelley in his book, he didn’t need to: the allusion to Frankenstein was perfectly clear in the title. Davis was writing in a long tradition of reading the monster imagery of Frankenstein through the technological lenses of Marxism. Based in London for much of his career, Marx himself was likely influenced by the massive cultural impact of Shelley’s Frankenstein and her husband Percy’s radical political poetry, as they filtered through the nineteenth-century British socialist tradition.[15] Despite his stubborn dislike of Marxist hermeneutics and other social scientific readings of literature, the critic Harold Bloom was always the first to admit that “it is hardly possible to stand left of (Percy) Shelley.”[16] Given his revolutionary-era philosophical debts to Rousseau, Wollstonecraft, and Godwin, it is not surprising that Percy Shelley felt outraged by the news of the August 1819 “massacre at Manchester.”[17] The British calvary charged an assembly of 60,000 workers, killing some and injuring hundreds more. While living in exile in Italy with his pregnant wife, in deep mourning over the recent losses of their toddler William to malaria and infant Clara to dysentery, Percy composed a timeless lyric to summon the poor to non-violent protest. Not published until 1832 due to the poet's untimely death in 1822 and the poem's controversial argument, “The Mask of Anarchy” became an anthem for the peaceful liberation of people from the slavery of poverty and political oppression: "Rise like Lions after slumber In unvanquishable number-- Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you-- Ye are many—they are few."[18] Completed two years before Percy’s rousing defense of popular uprising against the power of the imperial state, Frankenstein made a parallel political point. Literary scholar Elsie B. Michie underscored that the tragic predicament of Frankenstein’s abandoned Creature fit what Marx would call, in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, the plight of “alienated labor.”[19] Modern capitalistic society cruelly severed the poor from the material sources and products of their own making. Frankenstein likewise left his Creature bereft of any benefits of the “bodies,” “work,” and “labours” by which “the being” had been shaped into “a thing” such as “even Dante could not have conceived.”[20] When read against the background of Shelley’s novel, Marx’s theory of alienated labor recalls the dynamic of confrontation and separation that drives the conflicted yet magnetic relationship of the Creature with his technological maker. Taken out of the context of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, some of Marx’s words could easily be mistaken for a commentary on Frankenstein, as in: “the object that labour produces, its product, confronts it as an alien being, as a power independent of the producer.”[21] While capitalism produced the workers from its elite economic control of the tools of science, technology, and economics, the workers received no benefit from those same tools that a truly benevolent maker might have otherwise bestowed upon them. What could such a creature do but confront their maker with a demand for the goods necessary for the development of their humanity? In his 1857-58 “Fragment on Machines” from the Grundrisse, Marx rather poetically captured the process of human alienation from the products of their own technological labors: "Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified."[22] Reworking the twin Greek myths of Prometheus, in which the titan molds humanity from clay and then forges the mortals’ rebellion from the gods through the gift of fire, Marx follows Shelley in depicting human beings as self-replicating machines: for they are artificial products of their own willful mind to dominate and transform nature through technology. As the political philosopher Marshall Berman argued in All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (1983), Marx’s bourgeoisie is a Promethean “sorcerer” akin to “Goethe’s Faust” and “Shelley’s Frankenstein,” for it created new and unruly forms of artificial life that in turn raised “the spectre of communism” for modern Europe.[23] What Mike Davis has done so brilliantly, in the spirit of both Marx and the Shelleys, is to use this nineteenth-century techno-political imaginary to conceptualise humanity’s responsibility for the self-destructive course of pandemics in our time. Generations of readers of Frankenstein have felt compelled to pity the Creature, despite his train of crimes, and come to view him as a product of the fevered madness of his father-scientist. In this rhetorically persuasive Shelleyan tradition, Davis pushes his readers to see Covid-19 and other pandemics as products of the myopic mindsets of the human beings who selfishly let them loose upon the world. With the rise of the novel coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, Davis stoically set up his home office in his garage. As most countries around the globe went under lockdown during the endless winter of 2020, he sat down to update his book The Monster at Our Door for the second time.[24] Like Shelley and many writers of political science fiction after her, from Octavia Butler to Margaret Atwood to Emily St. John Mandel, the historian had predicted that a new, deadly, and devastating severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) would visit the planet in the twenty-first century.[25] Reports from the World Health Organisation had sparked Davis’s concerns about the latest iteration of the avian flu, or H5N1 influenza.[26] H5N1 had fast and lethal outbreaks in 1997 and 2003—while exhibiting a terrifying 60% mortality rate.[27] It passed from chickens to humans in Hong Kong in 1997, and, on a much more alarming scale, through “commercial poultry farms” in South Korea, China, Thailand, Vietnam, and other regions of Southeast Asia in 2003, via a “highly pathogenic” and “novel strain,” H5N2.[28] Like the epidemiologists, ecologists, and anthropologists whose work he studied, the historian feared that the “Bird flu” could erupt into a pandemic that might kill more than the deadliest virus of the twentieth century.[29] Davis recounted that an estimated “40 to 100 million people”—including his “mother’s little brother”—had been taken by the H1N1 avian influenza of 1918.[30] The newspapers at the time described the pandemic as the “Spanish Flu,” even though it started in the United States and elsewhere.[31] Because Spain remained neutral during the First World War, its press went uncensored. Spanish newspapers took the lead in reporting cases of the rising international wave of influenza. Far from war-torn continental Europe, the first recorded human outbreak of this flu mutation—which swiftly flew from birds to people—in fact began in a rural farming community and military base in Kansas.[32] A dreadful re-run of 1918 loomed in our near future, Davis insisted, if nations did not prepare for the worst. Governments needed to reduce “the virulence of poverty,” improve health care, and stockpile medical and protective equipment.[33] They had to regulate international trade, factory farming, and flight travel with an eye toward protecting public health from a resurgence of uncontrolled zoonotic viral respiratory infections. And they must support the best virology and vaccine research before the next epidemic snowballed into a global economic and political disaster. Under lockdown last April, Davis changed the title of his updated book to The Monster Enters, to mark a shift in his historical perspective. Just a few weeks earlier, disease ecologist Peter Daszak announced in a New York Times op-ed that we had officially entered the “age of pandemics.”[34] The monster pandemic of our political nightmares was no longer the threat of the avian flu at our door. It had already entered our world as SARS-CoV-2—a novel coronavirus thought to have been initially transmitted from bats to humans near Wuhan, China—and it was leaving a mounting set of economic, social, and political disasters in its wake. More of these novel and volatile contagions stood on the horizon like shadows of Frankenstein’s creature cast over the Earth. “As the hour of the pandemic clock ominously approaches midnight,” Davis had reflected on the last page of The Monster at Our Door, “I recall those 1950s sci-fi thrillers of my childhood in which an alien menace or atomic monster threatened humanity.”[35] Without vaccines to stop their circulation across nations, these viral mutations threatened to destroy their human creators like Frankenstein’s creature had done. Ironically, they could upend the globalised economic and political systems that had proliferated their diseases through international trade, travel, and economic inequality. Never purely natural phenomena, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and the latest strain of the avian flu were in fact the products and “plagues of capitalism.”[36] In the chapter titled “Plague and Profit,” Davis made explicit his debt to both Marx and Shelley. He gave the name “Frankenstein GenZ” to the virulent “H5N1 superstrain—genotype Z.”[37] At the turn of the twenty-first century, poultry factories in China unwittingly bioengineered this deadlier strain of H5N1, in the aftermath of the 1997 outbreak in Hong Kong. By inoculating ducks with an “inactivated virus” and breeding them for slaughter in their processing plants, they created a new and potentially levelling form of the avian flu, H5N2.[38] Almost two centuries before our current historical seer Mike Davis, Mary Shelley saw the monster pandemic coming for us in the future. The concluding volume in my trilogy on Shelley and political philosophy for Penn Press--The Specter of Pandemic—is about why she and some of her followers in the tradition of political science fiction have been able to predict with uncanny accuracy the political and economic problems that have beset humanity in the “Plague Year” of two thousand and twenty to twenty-one.[39] For Shelley, the reasons were deeply personal. She experienced an epidemic of tragedies on a depth and scale that most people could not bear. During the five years she lived in Italy from 1818 to 1823, the young author, wife, and mother saw the infectious diseases of dysentery, malaria, and typhus fell three children she bore or cared for, before her husband Percy drowned, at age twenty-nine, in a sailing accident off the coast of Tuscany. Her emotional and intellectual resilience in the face of the many plagues upon her family is what made her a visionary sf novelist, existential writer, and political philosopher of pandemic. [1] Justin Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus; or, Pandemic, Panic, Pandaemonium,” Crisis & Critique 7:3 (2020), 41-60; Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert, eds., The Journals of Mary Shelley (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, [1987] 1995), 220. [2] Clemens, “Morbus Anglicus,” 47-48. [3] Ibid., 43, 45. [4] Ibid., 50. [5] Ibid., 52. [6] Shelley, The Last Man, 183. In March 1820, Shelley noted Percy’s reading Hobbes’s Leviathan, sometimes, it seems, “aloud” to her. See Shelley, Journals, 311-313, 345. The epigraph for Frankenstein is drawn from Book X of Milton’s Paradise Lost: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay/To mould me man? Did I solicit thee/From darkness to promote me?” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism, ed. J. Paul Hunter, second edition (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 2. [7] Shelley, Frankenstein, 69, 102, 119. [8] Ibid., 35. [9] Eileen Hunt Botting, Artificial Life After Frankenstein (Philadelphia: Penn Press, 2020), introduction. [10] Mary Shelley, The Last Man, in The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley, ed. Jane Blumberg with Nora Crook (London: Pickering & Chatto, [1996] 2001), vol. 4, 176. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid., 139. [13] Ibid., 144. [14] Mike Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu, and the Plagues of Capitalism (New York: OR, 2020). [15] Chris Baldick, In Frankenstein’s Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 132, 137. [16] Harold Bloom, Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The Power of the Reader’s Mind over a Universe of Death (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 183. [17] “Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘The Mask of Anarchy (1819),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/PShelley/anarchy.html. [18]Ibid. [19] “Elsie B. Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990),’” accessed November 28, 2020, http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Articles/michie1.html. [20] Shelley, Frankenstein, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36. [21] “Michie, ‘Frankenstein and Marx’s Theories (1990).’” [22] Karl Marx, “The Fragment on Machines,” The Grundrisse (1857-58), 690-712, at 706. Accessed 28 November 2020 at https://thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf [23] Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983), 101. [24] Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu (New York: New Press, 2005); Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of the Avian Flu. Revised and Expanded edition (New York: Macmillan, 2006). [25] Eileen Hunt Botting, "Predicting the Patriarchal Politics of Pandemics from Mary Shelley to COVID-19," Front. Sociol. 6:624909. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.624909 [26] Davis, The Monster Enters, 87-100. [27] Natalie Porter, Viral Economies: Bird Flu Experiments in Vietnam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 2. [28] Porter, Viral Economies, 1-2.; Davis, The Monster Enters, 120-23. [29] Ibid. [30] Davis, “Preface: The Monster Enters,” in The Monster at Our Door, 44-47. [31] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin, 2004), 171. [32] Ibid., 91. “1918 Pandemic Influenza Historic Timeline | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC,” April 18, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/pandemic-timeline-1918.htm. [33] Davis, The Monster Enters, 53. [34] Peter Daszak, “Opinion | We Knew Disease X Was Coming. It’s Here Now.,” The New York Times, February 27, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/opinion/coronavirus-pandemics.html. Davis cites Daszak’s article with David Morens and Jeffery Taubenberger, “Escaping Pandora’s Box: Another Novel Coronavirus,” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (2 April 2020) in his introduction to The Monster Enters, 3, 181. [35] Davis, The Monster Enters, 180. [36] See the subtitle of Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu and the Plagues of Capitalism. [37] Davis, The Monster Enters, 119, 122 [38] Ibid. [39] Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations Or Memorials of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as Well Publick as Private, Which Happened in London During the Last Great Visitation in 1665 (London: E. Nutt, 1722). by Sean Seeger

What is the relationship of queer theory to utopianism?