by Emmanuel Siaw

Although there is a popular drive towards a much-touted ‘pragmatic’ understanding of global events, an ideological theory of international relations has become more important due to the complexity of these events. This means the creation of new methodologies and conceptions to demonstrate that the adaptability and everydayness of ideologies has become even more essential in a dynamic world. One way of doing this is to treat ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. What this also means is to further enhance the bid to see ideologies as phenomena that are “necessary, normal, and [which] facilitate (and reflect) political action”.[1] In this piece, I argue that a contextualisation of socialism and classical liberalism into the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological debate, respectively, has been the ideological binary pervading Ghanaian politics since independence despite the changes in government and personnel.

Making a case for thought and action through ideological contextualisation Many African governments have not hidden their love for or association with existing macro-ideologies like liberalism, Marxism, and socialism. Yet, for most of the journey of ideological studies, since its beginnings with Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Africa has been overlooked due to the preoccupation with the assumption that African states have little room for policy manoeuvre due to foreign influence—a position captured in the extraversion and dependency arguments.[2] This has been consolidated by the view that the rhetoric and actions of policymakers do not conform to dominant ideologies, or external influences appear to override the ideological objectives of African governments. In this article, I argue against this position, emphasising that dependency is not akin to a lack of ideology; and demonstrate that ideology is indeed relevant in Ghanaian politics as it will be in the rest of Africa. What I suggest is that although the ideas of Ghanaian governments may not be pure or conform fully to the core tenets of existing macro-ideologies, paying attention to contextually relevant ideological variables and how they interact with macro-ideologies is a viable way of understanding the dynamic role of ideas in Ghanaian and African politics, in general. Several studies have shown that events and politics in Africa are as dynamic and interesting as politics elsewhere.[3] Hence, I agree with Thompson that “if the study of ideology helps political scientists to understand the politics of the West, then the same should also be true for post-colonial Africa. Any book seeking to explain the politics of this continent, therefore, needs to identify and explore the dominant ideologies that are at work in this environment”.[4] I first admit that the African context is unconventional and atypical. Unconventional because ideologies are embedded in context and the existing macro-ideologies evolved from contexts and situations outside the African conditions. Interestingly, in a lecture by Vijay Prashad (Indian historian) he demonstrated how India and China have integrated Euro-American ideologies, similar to the point I am making here.[5] Second, I acknowledge the tight spaces in terms of structural institutional constraints, history and the level of dependency of African states that makes it quite unique from the politics of the global North. Therefore, to embark on this analysis of ideology in an unconventional setting requires certain theoretical adjustments to reflect the dynamic conditions of the politics in African states. My approach to these adjustments is what I call an Ideological Contextualisation Framework (ICF). Ideological contextualisation is a coined concept that connotes that ideologies and ideological analyses should consider the immediate environment and historical experience of the cases being explored. It is inspired mainly by the works of Michael Freeden and Jonathan Leader Maynard on ideology. In the process of policy-making, large abstract political ideas must be translated into actual decisions, policy documents, plans, and programmes of action. To do that, ideological concepts need to be made to ‘fit’ a particular place, time, and cultural context. Part of this bid to make ideologies ‘practicable’ in different contexts flows from the field of comparative social and political thought to a more recent conception of comparative ideological morphology by Marius Ostrowski.[6] For instance, James McCain’s experimental analyses of scientific socialism in Ghana, published in 1975 and 1979, reveal that it does not conform to the assumptions of orthodox ‘African Socialism’.[7] Instead, what a leader like Nkrumah meant with this ideology was to exploit its political mobilisation feature within the Ghanaian cultural context. This is because it was a response to the needs at the time. Emphasis is, therefore, placed on the “native point of view” and “whatever that happens to be at any point in time”.[8] The essence of contextualising ideas is to avoid the analytical shortfalls dominant in the African context occasioned by analyses that focus on either the overbearing role of ideology, which leads to policy failures, or the non-existence of ideologies at all. These analyses fail to capture the dynamics of ideology and what falls in-between these extremes. While Ghana is unique, its conditions resemble what happens in many African countries. This year, Ghana’s celebrates 65 years of gaining its independence and of being the first sub-Saharan African country to do so in 1957. Since independence, there have been highs and lows on the development spectrum. Ghana has experienced military, authoritarian, civilian, and democratic governments over the last six and half decades. At independence, Ghana was among the most economically promising countries in the world, but the 2020 Human Development Index Report ranked Ghana 138th in the world. Ghana has not experienced a full-blown civil war or war with other countries but has had pockets of internal conflicts. Over the years, Ghana’s politics and policy-making have also been a dynamic mix of successes and challenges that characterises many African states. Just like many exegeses of politics in other African states, it is common to hear commentary in Ghana about how genuine commitment to ideology has ended or how it has lost its traction for understanding Ghanaian politics, especially after the Nkrumah era. In one of such instances Ransford Gyampo, in his study on Ghanaian youth, emphasises that ideology does very little in orienting party members, especially the youth.[9] He further insisted on ideological purity as a conduit for organising the youth members. However, scholars like George Bob-Milliar have argued that political parties supply ideologies for their better-informed members who vote based on ideological differences.[10] For Franklin Obeng-Odoom and Lindsay Whitefield, such ideological differences rarely exist as neoliberalism has become a supra-ideology that pervades the different ‘isms’ to which parties subscribe.[11] Although the challenge here lies in the mischaracterisation of ideology, the jury is still out on ideology and its role in Ghanaian politics, just like many other African countries. A recalibrated look at the history of Ghanaian politics from the perspective of contextualisation presents a situation where ideology stretches far beyond magniloquence. Ideology and the history of Ghanaian politics What I do here is to briefly explore Ghana’s political history and demonstrate that ideology is and has indeed been relevant to Ghanaian politics. This ideology is typified by the ideological dichotomy between Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, which has lasted from the late 1940s to date. As I will explain below, the late pre and early post-independence period was characterised by two groups: one led by Dr Kwame Nkrumah, leader of the Convention People’s Party (CPP) that eventually won independence for Ghana in 1957. On the other hand was the opposition United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC)—the party that brought Nkrumah to Ghana from London—led by Joseph Boakye Danquah, and later by Kofi Abrefa Busia and Simon Diedong Dombo. These two groups agreed and disagreed on many policy issues based on their ideologies and such duality has characterised Ghana’s political milieu since independence. I limit this discussion to the period from independence to the end of Kufuor’s administration in January 2009. The beginnings of the politics of ideas in Ghana was more profound during the late colonial period after the split between Kwame Nkrumah and other members of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) that manifested in the formation of different political parties till Nkrumah’s overthrow in 1966. After this split in 1949, Nkrumah formed the Conventions Peoples Party (CPP) and went ahead to win independence for Ghana in 1957. The UGCC, on the other hand, transformed into different parties which contested and lost to Nkrumah in all the pre and early post-independence elections (1951, 1954, 1956 and 1960).[12] On the internalised level, the two groups were split by their commitment to socialism, African socialism, scientific socialism, or what later came to be known as Nkrumaism for the CPP and classical liberalism or what came to be known as property-owning democracy for the UGCC. One thing to note here is that the changes in vocabularies, as mentioned above and a common feature across subsequent administrations, is a practical manifestation of the constant search not just for a vocabulary that fits the Ghanaian context but ideas that reflects the aspirations of governments. These party formation dynamics have even deeper ideological outcomes for the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo group on some key issues. For instance, beyond their internalised socialist ideas, the CPP had what they called ‘African personality’ while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred the ‘Ghanaian personality’ beyond classical liberalism. What the CPP or Nkrumah administration meant by ‘African personality’ was for “recognising that Africa now has its personality, its own history and its own culture and that it has made valuable contributions to world history and world culture”.[13] According to Nkrumah, ‘African personality’ was to demonstrate to the world Africa’s “optimism, cheerfulness and an easy, confident outlook in tackling the problems of life, but also disdain for vanities and a sense of social obligation which will make our society an object of admiration and of example”.[14] The Danquah-Busia-Dombo group introduced the idea of Ghanaian personality counter the CPP’s African personality. By Ghanaian personality, they meant “giving more meaning to this freedom [republican status] to express our innermost selves”.[15] This meaning was contextual as it was the period after two harsh laws were passed by the Nkrumah government, CPP. The Avoidance of Discrimination Act (ADA) of 1957 banned all regionally based political parties and forced all opposition parties to merge into the United Party (UP). The Preventive Detention Act (PDA) of 1958 allowed for people to be detained without trial for five years if their actions were deemed a threat to national security. For the opposition, the best way to project an African personality, in the spirit of freedom (decolonisation) and unity (African integration), was first to project a Ghanaian personality that prioritised the same rights. The two ideas—African and Ghanaian personality—represented their contextual aspirations and significantly impacted their policy preferences and approach. They manifested in policy differences in issues such as how and when independence should be granted, how much Ghana should be involved in the politics of other African states, perceptions about colonial metropoles and future relations with them, how to approach regional integration, economic diplomacy and foreign policy, in general. It also influenced the domestic development goals and approaches. To give some few policy examples, the CPP fundamentally wanted independence ‘now’ regardless of the consequences while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo wanted independence within the shortest possible period through what they perceived as legal and legitimate means. Parsimoniously on regional integration, while the CPP preferred rapid regional political unity on the continent with all African states, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred functional regional integration starting with economic and from within the West African subregion. In terms of domestic developmental approach, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group always preferred alternative routes to Nkrumah’s state-led and managed Import Substitution Industrialisation and common or state ownership. Throughout this period, the interpretation of ideological components such as economic independence was a key part of the ideologies of the two groups. Even though they both considered it a crucial concept, their interpretations varied, leading to some significant differences in policies and approaches. However, the growing power of contextual structures such as the Bretton Woods has occasioned similar ideas and policy path-dependence over time since the overthrow of Nkrumah in 1966. A cursory look at the IMF and World Bank interventions in Ghana since 1967 shows a common neoliberal trend in approaches to resuscitate Ghana’s economy. This has later accounted for some sort of ideological convergence that some scholars have identified in their study of Ghana’s Fourth Republic (since January 1993). For a developing country that is yet to address some of its basic needs, like infrastructure and education, there are points of convergence in terms of common components that address basic developmental needs. They translate into policies that can, in most cases, appear similar because they have similar inspirations. One of such examples is how even the different ideological factions within the CPP and other political parties acknowledged the need for independence and formed some sort of ideological convergence on that regardless of their fundamental ideological differences. This late colonial and early post-independence period of ideological dichotomy and similarities set the stage for subsequent administrations amidst variations. I explain these dynamics below. The National Liberation Council (NLC) that overthrew the CPP government pursued policies that showed ideological consistency with the anti-Nkrumah group, Danquah-Busia-Dombo. This was buttressed by the fact that a one-time opposition leader during the CPP administration, who later went into exile, Prof. Kofi Abrefa Busia, became a leading member of the administration and headed the Centre for Civic Education—an organisation responsible for public education on civil liberties and democracy. The administration shifted Ghana’s domestic and foreign policy based on that ideological dichotomy flowing from the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo debate. More instructively, they shifted to framing liberal-oriented development programmes and building stronger relations with the West—something the Nkrumah-led CPP administration was wary of. When the Progress Party (PP) took power in 1969, it continued what the NLC began after the overthrow of Nkrumah’s CPP in 1966. Led by Prof. Busia himself, the PP government pursued policies that were ideologically at variance with Nkrumah but in line with ideas espoused by the UGCC before independence. For instance, the belief in non-violent decolonisation occasioned their policy to discontinue Ghana’s financial support for the African nationalists in South Africa, preferring dialogue with apartheid South Africa instead. In 1969, the Aliens Compliance Order promulgated by the government to return undocumented migrants affected many Africans and had implications for Ghana-Nigeria relations under subsequent governments had to address. For instance, in 1983 the Shehu Shagari government of Nigeria’s decision to deport undocumented migrants (half of the about three million deportees were Ghanaians) was popularly interpreted as a retaliation for Ghana’s 1969 deportation policy.[16] Although economic reasons were cited for Nigeria’s decision, it is obvious that what Ghana, or the PP government did in 1969 made the Nigerian government and people more relentless to follow through with their decision in what came to be known popularly as ‘Ghana must go’—a name also associated with the type of bag the migrants travelled with.[17] Based on Nkrumah’s relations with African settlers, the Aliens Compliance Order is a policy the CPP government would not have embarked on or fully encouraged.[18] Under the CPP government, Ghana was touted as the Mecca for African nationalists due to the government’s warm reception. Another point of difference between the two groups was the disagreement of large-scale industries of Nkrumah and the role of the state their building and operation. Therefore, a lot of Nkrumah’s industries were either discontinued or privatised. Some of these industries include the Glass Manufacturing Company at Aboso, in the Western Region, GIHOC Fibre Products Company and the Tema Food Complex Corporation, both in the Greater Accra Region.[19] The PP government was overthrown by an Nkrumaist oriented junta, the National Redemption Council (NRC), who tried to restore Ghana to its putative glorious years under Nkrumah by resuming Ghana’s contribution to African nationalist movement against Apartheid South Africa, supporting African states in several endeavours, resuming Nkrumah’s industrialisation agenda, pursing a domestication policy that aims to at food self-sufficiency, and repudiating foreign (especially Western) debts. These policies were grounded in the contextual ideological components of economic independence and Pan-Africanism, whose interpretations were closer to the CPP administration’s intentions. This Acheampong-led NRC government, and later Supreme Military Council (SMC I) administration, was overthrown by an Edward Akuffo-led Supreme Military Council (SMC II) who, though they orchestrated a palace coup to overthrow Acheampong, did not deviate much from the previous administration’s pro-Nkrumah policies. Instead, they were more focused on restoring Ghana to multiparty elections. However, this administration lasted for only eleven months and was overthrown by a group of young militants, the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), who took power until after the 1979 elections and handed over to a democratically-elected People’s National Party (PNP). The PNP government, led by Dr Hilla Limann, was one of the latter attempts to bring introduce a full-fledged Nkrumaist party after the CPP was banned before the 1969 elections. Although to the disappointment of many Nkrumaists, this government did not pursue politics based on the ideas of Nkrumah’s CPP, its policies were somewhat closer to what the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred—for instance, in attempting to the IMF for bailouts and broader pro-West economic relations. This was one of the reasons why the Rawlings-led military junta, now the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), returned to overthrow the PNP government in 1981. Although this group (PNDC) was generally touted as radical and anti-West, their internal ideological dynamics resembled the broader ideological dichotomy between the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo groups. Within the PNDC government was a group that aligned itself to Nkrumah’s CPP ideology and, for instance, were wary of the West, former colonial metropoles and programmes like the Structural Adjustment Policies. On the other side were those who were touted as less radical and ideologically closer to the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, who were rather willing to engage the World Bank and IMF through the Structural Adjustment Programmes. This internal dialectic shaped the government’s domestic and foreign policy. However, from 1984, there seemed to be a broader consensus within the party as one whose ideology and politics was shaped by contextual structures, which made it difficult for the government to pursue policies just based on its internalised ideology. The PNDC later metamorphosed into the National Democratic Congress (NDC) when the government, under several domestic and international pressures, adopted multiparty democracy and elections from December 1992. After leading Ghana democratically for eight years, the NDC lost the December 2000 elections to the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Coming directly from the Danquah-Busia-Dombo tradition, the NPP government led by John Agyekum Kufuor pursued policies mainly in line with what the forerunners have proffered, especially against Nkrumah’s policies. For instance, they created an enabling environment for private property ownership and entrepreneurial development, including encouraging foreign investors, a strengthened relationship with the West, and for a greater emphasis on its economic and democratic values. To further the idea of Ghanaian personality that was based on respect for humanity and human rights, the government opened itself up for review by other African states through the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), and took steps to pursue regional integration from a functional economic perspective. From the discussions above, a few things must be clarified regarding Ghana’s ideological history. Socialism (for Nkrumaists) and classical liberalism (for the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group) have been the two dominant internalised macro-ideological leanings in Ghana, since independence. However, in an ever-changing, developing, and dynamic context like Ghana and the rest of Africa, these ideologies cannot function in their pure form, in their influence on policies. Therefore, in Ghana and Africa, I argue that context matters. Looking at the Ghanaian case teaches us three main things analytically about the African continent. First is the dominance macro-ideologies or the fact that we cannot ignore ideologies like liberalism, Marxism and socialism as they are usually primary to the ideological structure of many governments. Second is the power and relevance of contextual structures, like regional organisations and the Bretton Woods, to produce ideas that African governments take on or adjust to because of their putatively weaker position. Constructivists have long emphasised the learning function of states. Third is existence of historical conditions that have evolved into ideas over time. Chatterjee Miller’s study of India and China’s foreign policy reveals a longue durée ‘post-imperial ideology’, comprising a sense of victimisation and driven by the goal of recognition and empathy as a victim of the international system to maximise territorial sovereignty and status.[20] In the Ghanaian case, some of these conditions include economic independence, Africa consciousness and good neighbourliness. While these conditions pervade across different governments, the interpretations and approaches vary. Across the continent, these conditions of ideological value may vary, but they are very relevant to any analysis of ideology. This affords us the laxity to focus on ideological components, treating the macro-ideologies as part of the components. One of the reasons why ideology has been overlooked is the assumption that African states are weaker and have very little policy options because a lot of their policies are dictated by foreign powers. However, looking at ideology in itself is a bid to explore existing spaces, shed more light on those that have so far been neglected, and begin analyses of African politics from a perspective that acknowledges a certain contextual relevance and policy constraints. To do this, we should see ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. Conclusion The place of ideology in global politics has been evolving in methodologies and vocabularies. This article is borne out of the bid to take Africa more seriously in that conversation by paying more attention to the contextualisation of ideas. This is not to say that ideologies explain everything, but it is to highlight the relationship between the interpretive value of ideology and contexts, and to emphasise that such relationships have a significant effect on African politics. The Ghanaian ideological context has been dominated by different shades of the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological dichotomy, characterised by an interaction between big-isms, contextual components and structures. These varieties of Ghanaian nationalism is bound to manifest differently in other African cases, but its conceptual proposition of interaction between context and ideas is very relevant. It demonstrates an understanding of African politics from within. Therefore, while this application gives us an indication and confidence to probe more into ideologies and policy-making in other African states, it also responds to the agency question which is fundamental to domestic and foreign policies. [1] Freeden, M. (2006). Ideology and Political Theory. Journal of Political Ideologies, 11(1), p. 19. [2] Bayart, J. F. (2000). Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion. African Affairs, 99, 217–267; Robertson, J., & East, M. A. (Eds.). (2005). Diplomacy and Developing Nations: Post-Cold War Foreign-Policy Structures and Processes. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [3] Brown, W., & Harman, S. (Eds.). (2013). African Agency in International Politics. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [4] Thompson, A. (2016). An Introduction to African Politics. In Routledge Handbook of African Politics (4th Edition). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p. 32. [5] Vijay Prashad (2021) What's the Left to Do in a World on Fire? | China and the Left. Public Lecture Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vd8w3ONjv6Y&t=453s Accessed 13th March 2022 [6] Ostrowski, M. S. (2022). Ideology Studies and Comparative Political Thought. Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), 1–10. [7] McCain, J. (1975). Ideology in Africa: Some Perceptual Types. African Studies Review, 18(1), 61–87; McCain, J. (1979). Perceptions of Socialism in Post-Socialist Ghana: An Experimental Analysis. African Studies Review, 22(3), p. 45. [8] Ibid, p. 46 [9] Gyampo, R. E. Van. (2012). The Youth and Political Ideology in Ghanaian Politics: The Case of the Fourth Republic. Africa Development, XXXVII(2), 137–165. [10] Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2012). Political Party Activism in Ghana: Factors Influencing the Decision of the Politically Active to Join a Political Party. Democratization, 19(4), 668–689. [11] Whitfield, L. (2009). “Change for a Better Ghana”: Party Competition, Institutionalisation and Alternation in Ghana’s 2008 Elections. African Affairs, 108(433), 621–641; Obeng-Odoom, F. (2013). The Nature of Ideology in Ghana’s 2012 Elections. Journal of African Elections, 12(2), 75–95 [12] Frempong, A. K. D. (2017). Elections in Ghana (1951-2016). In Ghana Elections Series (2nd Edition). Digibooks. [13] Potekhin, I. (1968). Pan-Africanism and the struggle of the Two Ideologies. Communist, p. 39. [14] Kwame Nkrumah: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 4th July, 1960, col. 19 [15] S. D. Dombo: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 30th June 1960, col. 250 [16] Aluko, O. (1985). The Expulsion of Illegal Aliens from Nigeria: A Study in Nigeria’s Decision-Making. African Affairs, 84(337), 539–560. [17] Graphic Showbiz (21st May, 2020) Ghana Must Go: The ugly history of Africa’s most famous bag. Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/entertainment/features/ghana-must-go-the-ugly-history-of-africa-s-most-famous-bag.html#&ts=undefined Accessed 13th March 2022 [18] Although in 1954, when Nkrumah was the Prime Minister and three years before Ghana’s independence, some Nigerians were deported; but not on the scale, in terms of number and government’s involvement, of what happened in 1969. After independence, Nkrumah’s support for African immigrants and other African states seems to have overshadowed the 1954 deportation of Nigerians. [19] Ghana News Agency (28th September 2020) Ghana: 'Revive Nkrumah's Industries'. Retrieved from https://allafrica.com/stories/202009280728.html Accessed 13th March 2022 [20] Miller, C. M. (2013). Post-Imperial Ideology and Foreign Policy in India and China. Stanford University Press. by Erik van Ree

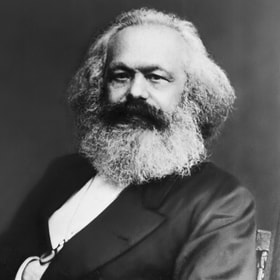

Measured against the number of those who called themselves his followers, and given the speed with which these “Marxists” after 1917 laid hands on a substantial part of the globe, Karl Marx, in death if not in life, was one of the most successful people that ever lived. He falls in the category of conquerors, Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan, or of religious prophets with the stature of Jesus of Nazareth and Mohammed. The spectacular collapse of much of the communist world, of course, substantially detracts from Marx’s posthumous success, but it doesn’t annul “Marxism’s” earlier triumphs.

Marx’s twentieth-century followers reconfigured his ideas (as far as these were available to them at all) to the point of unrecognisability. The fact that both Pol Pot and Mikhail Gorbachev could wrap themselves in the master’s flag speaks volumes. But the fact remains that on whatever grounds and with whatever degree of justification, dozens of millions worldwide, on an historically rather abrupt time scale, began to call themselves “Marxists”. We follow Karl Marx. Why did these millions make this person their emblem? The question has no easy answer, if only because Marx’s worldwide success is part of the larger question of why communism, Marxist or not, for a time became the world’s wave of the future. The fact that the radically estranged twins, social democracy and communism, made spectacular strides in the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, as such, surely, has little to do with anything Karl Marx ever did or wrote. But why did so many socialists precisely select him and not, for example, Ferdinand Lassalle, Mikhail Bakunin or any other well-known radical onto whom to project their hopes and aspirations? I know why I did. If I remember correctly, I regarded myself as a Marxist from the age of eighteen. Undergoing a rapid process of radicalisation, I served as a member of various Maoist groups in the Netherlands between 1973 and 1981. In the wake of this experience I lost my sympathies not only for the Chairman but also for the alleged founder of the movement, Karl Marx. But I do remember what attracted me to him. My first political love as a youth was anarchism. What, in my imagination, made Marx so much more attractive was the way he managed to combine radical combativeness, also found in anarchism, with a sober, scientific perspective. Obviously, personal experiences of half a century ago represent nothing more than that—one person’s history. But not only do memories and experiences inevitably colour any researcher’s work, they may even be quite helpful in formulating hypotheses. I believe with Karl Popper that, as long as hypotheses are testable, their original inspiration can never be held against them.[1] What, then, did Marx have to offer potential “followers”? He was, I believe, one of the modern era’s great visionaries. Marx was a man of unusually broad interests and activities, engaging as he did in philosophy, economics, law, political analysis, journalism, and radical activism. What made him stand out among other potential world-level socialist gurus was the breadth and enormous diversity and scope of his vision, the extraordinarily multifaceted quality of his work, potentially appealing to people living in very different kinds of societies and of very different social position, views and temperament. Many Marxes The literature about Marx’s life and thought is so extensive that it is impossible to oversee even for researchers who have dedicated their whole life to the subject, a category the present author does not belong to. But it seems to me that the main existing academic interpretations of Karl Marx insufficiently bring out what made this man special and fascinating to so many people. I find four interpretations of Marx of special interest and interpretive power, even though I do not feel completely comfortable with any of them. The first, Social Democratic Marx is to be met, for example, in Geoff Eley’s Forging Democracy. This Marx recognised the futility of Blanquist secret societies and insurrectionary committees, while instead embracing the model of the political party of the working class. Marxist Social Democratic parties wisely made good use of their parliamentary positions.[2] This Marx furthermore made socialism dependent on the material conditions created by industrial capitalism, thus altogether ruling out proletarian revolution outside the industrialised world. Wolfgang Leonhard was one authoritatively (and quite rigidly) to characterise Marx thus, back in 1962.[3] That Marx predicated proletarian revolution upon the conditions of developed industrialism has become something of an established truth. Recently the thesis was repeated, for example, by Terry Eagleton and Steve Paxton.[4] Social Democratic Marx was, furthermore, a radical democrat. If he sporadically referred to the “dictatorship of the proletariat” he was merely referring to the rule of the working class, i.e. to majority rule.[5] The second, Revolutionary Marx was a Bolshevik avant la lettre. This frame is less well represented in the academic literature but is certainly not to be ignored. Central in Michael Löwy’s reading of the insurrectionist Marx is the “permanent revolution”. Löwy’s Marx accepted that, in principle, proletarian-socialist revolution was doomed to remain a fantasy without a preceding, protracted stage of capitalist development and/or a bourgeois revolution. However, Marx nurtured some “brilliant but unsystematised intuitions”[6] to the effect that the proletariat might yet induce a “telescoped sequence”[7] compressing the two stages into one and seizing power before the bourgeoisie had completed its historical task.[8] Reidar Larsson perceptively observes that, when between 1846 and 1852 Marx was creating strategies for proletarian revolution in Germany and France these countries were still industrially backward themselves. According to Larsson, Marx believed that by the 1840s, capitalism, even if still underdeveloped, yet had reached the limit of its capacity for development, which is what made the proletarian revolution timely even then.[9] Even if I personally find the Revolutionary reading of Marx more convincing than the Social Democratic one, both readings are convincing enough, referring us as they do to different aspects of Marx’s thinking and practice. Alvin Gouldner’s attractive thesis of “The Two Marxisms” is built on the idea of two spirits coexisting in Marx’s breast, both real, the one objectivist, relying on historical-economic laws, and the other voluntarist and emphasising human agency. Gouldner leaves open the question of whether Marx’s ambivalent ideas were irreducibly fragmented or, perhaps, expressive of some deeper coherence. The great merit of his work from my point of view lies in clearly establishing the multifaceted, diverse quality of Marx’s thinking.[10] The third Marx, Man of the Nineteenth Century, was born in 2013. Biographer Jonathan Sperber reads Marx’s life and thought as the product of an era impressed with the French Revolution, philosophically coloured by G.W.F. Hegel, and shaken out of balance by early industrialisation. This biographer sidesteps the whole question of the possible influence of Marx’s ideas on the modern world, as essentially irrelevant.[11] Sperber’s focus on what caused “Marxism” rather than on what it brought about seems to echo Quentin Skinner’s suggestion that historians do better to explore what authors meant to convey and achieve in their own times, than to lose themselves in imaginary, universal, and timeless elements of these authors’ ideas beyond their context of origination.[12] But, then again, irrespective of what historians may believe, millions of others did think that Marx’s ideas were worth following, and they patterned their actions on what they believed were his guiding thoughts. Even if they may have been misrepresenting these thoughts, we must discover the secret of their extraordinary attractiveness. Finally, the fourth, Demystified Marx, created by Terrell Carver, was an activist journalist locked in everyday life. His “thinking” was valuable enough, even for radicals today, but it was action-oriented and lacked the academic rigour even to be called a “thought”. Most of Marx’s more theoretical writings were never published in his lifetime and were mere messy fragments without much coherence or consistency. After Marx’s death in 1883 an everyday activist was souped-up into the great, world-class philosopher that he never was.[13] It seems to me that Carver does the thinker Marx less than complete justice. Even if, for example, The German Ideology (1845–6) was never more than a collection of fragments, to my mind that doesn’t change much. Even as fragments the texts remain fascinating and contain insights of great theoretical and sociological interest.[14] Marx’s posthumous fame rested on his ideas, compressed into theories, rather than on any activist achievements. His less than spectacular activities for the Communist League and the First International had little to offer the creators of his cult. Friedrich Engels, Karl Kautsky, Georgy Plekhanov and the others, framed Marx as the creator of their doctrine, not as their original super-activist or exemplary underground fighter.[15] That returns us to the question of what it was in these ideas that attracted so many. Marx For All Marx’s intuitive genius, which after his death made his name victorious for a time, consisted in an uncanny ability to combine what seemed uncombinable and to spread his wings to the maximum. While he vigorously denied that he was a utopian, he assuredly was one. In the new communist world envisioned by him all means of production would be socialised under self-managing democratic communes; the state and the great societal divisions of labour would be overcome; scarcity itself would be overcome, and with it money, ending in a condition where all would receive according to their needs. Marx countered accusations of utopianism by offering proofs that the new communist order was inscribed in history by the sociological laws he had discovered. He thought of himself as a man of science. It doesn’t really matter whether Marx’s philosophical exploits were of sufficient stature to call him a philosopher; or whether Das Kapital is to be regarded as a scientific or as a metaphysical work, whether on our present standards or on those of 1867. What matters here is only that Marx projected an image of himself as a scientist. Whether we call it “Marxism” or not, what Marx worked out represented an unusually attractive proposition, appealing to those caught in the romantic allure of communist utopianism as much as to the less euphoric radical attracted to science and rationality. This pattern of balance repeats itself over and over again. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx called out the proletariat for the battle of democracy. In his comments on the Paris Commune he embraced radical participatory democracy. But Marx also accepted the need of repressive measures to ward off “slave-owners’ rebellions” against the victorious proletariat, while over the years, together with Engels, referring to a future “dictatorship of the proletariat”. The power of Marx’s formula rested precisely in this ambivalence. Both radical democrats and those temperamentally inclined to harsh measures and dictatorship could feel represented by him. Not surprisingly, Social Democrats and Bolsheviks alike were happy to recognise this man as their founder. Again, if Marx insisted that communism can strike root only in highly-developed industrial societies, he did not in fact rule out proletarian revolution in backward countries, thus accommodating socialists both from advanced, industrial and from economically backward nations. Marx represented modern capitalism as a system of exploitation of wage-labour resulting in the gradual pauperisation of the industrial workers. The notion of “surplus value”, produced by the workers but appropriated by the capitalist class, possesses great mobilising power in conditions where exploitation and poverty reign. But Marx’s conceptual apparatus was encompassing enough to allow his followers to cast their nets far beyond these conditions. The concepts of “alienation” and “commodity fetishism” allowed later Marxists to remain in business to critique conditions in prosperous, post-industrial consumer societies, a form of society not even in existence in Marx’s own lifetime. Coherence The question remains of how to define the structure of Marx’s thought. How did Marx himself deal with his own thinking’s remarkably wide range and its concomitant ambivalence and contradictoriness? Where all these many ambivalent elements somehow welded together into an overarching intellectual structure, or were the contradictions indeed irreducible? Was there a system in Marx at all? There was surely not, insofar as his views on philosophy, history, politics, and economics do not hang together logically, but are best seen as separate endeavours. But it does not follow that he would not have been bothered by obvious inconsistencies and incoherence. Marx’s preoccupations shifted. Whereas the “Young Marx” was preoccupied with the problem of alienation, that theme later receded into the background, with the question of exploitation taking centre stage. But shifting interests are a far cry from contradiction. Marx regarded exploitation and alienation as the two downsides of the same coin of any social order based on private ownership, division of labour and the state. “Marxism” can, then, easily be framed as a single theoretical perspective speaking to the two conditions of exploitation and consumerism. It does not seem to have bothered Marx overly much that many of his extraordinary insights remained mere attempts, false starts, and fragments. Nobody stopped him from working out a formal definition of “class”, a crucial concept in his work. Marx could easily have accomplished that task, but he never did. Neither did he work out theories of the state or the nation, entities he wrote about all the time. Even his expositions of what came to be called “historical materialism” remained few and far between, and they were formulated loosely, sometimes downright sloppily, and in very general terms. Not a system builder, then. But this is not the whole story. Das Kapital follows a carefully crafted, deductive plan, based on clear and unequivocal definitions of “value”. Marx was immensely proud about his “discovery” that workers sell not their “labour” but their “labour power”, a conclusion that made his system logically flawless and allowed him to deduce “surplus value”. His argument that the expropriation of surplus value, i.e. capitalist exploitation, is based on equal exchange between workers and capitalists betrays great logical elegance. Marx was certainly not uninterested in coherence across the board. Achieving it could even be an obsession. All my three recent articles on Marx touch on the problem of coherence. They discuss, respectively, “permanent revolution”; Marx’s racism, which I argue was substantial and to a point theoretically grounded; and his views on the human passions as drivers of the developing productive forces and of revolution.[16] My particular interest goes out to such elements in Marx’s work as might be regarded as marginal but which on a closer look were significant. I find it especially interesting to explore how and if Marx made such eccentricities consistent with his other views more familiar to us, i.e. the problem of coherence. In exploring a historical personality’s thought, my primary interest goes out to its structure, how and to what degree it all hangs together—if at all. I realise that “finding coherence” not only carries the risk of finding what one seeks but also goes against the grain: the spirit of the times is rather about finding incoherence. Those affected with the postmodern sensitivity take pleasure in demonstrating that the apparent order we discover in theoretical structures really exists only the eye of the beholder. With the postmodern primacy of language and the discarding of the author as centred subject, the coherence-seeking thinker becomes a deeply counter-intuitive proposition. Postmodernity echoes the Buddhist view of the mind as a loose collection of fragments only weakly monitored by an illusionary sense of self. On the contrary, I work under the assumption that the individual mind to a point is centred and will attempt to hold the fragments together to avoid disintegration. This is never more than a hypothesis. Sometimes I have to admit defeat; as when, after much fruitless puzzling, I had to conclude that, whether the elderly Joseph Stalin’s political philosophy was more of the Marxist or of the Russian-patriot cast was a question he did not know the answer to any more than we do.[17] Permanent Revolution, Race, the Passions Back to Marx. In Löwy’s reading, “permanent revolution” is a highly significant element of Marx’s thought, but at basis remains an alien body. Capitalism must run its course. It must create a developed industrial infrastructure and must have exhausted its capacity for development for conditions of proletarian revolution to become mature. In economically backward conditions proletarian revolution is, then, at best, an odd occurrence—something that really couldn’t happen. Löwy solves the problem by assuming that Marx believed the capitalist and socialist stages exceptionally could be “telescoped” into one. But even then, the revolution must be saved from certain doom by revolutions in other, more developed nations. On this reading, Marx’s permanent revolution remains a very conditional, messy, and ad hoc proposition, inspired by revolutionary impatience. I believe there was considerably more logic and consistency to Marx’s revolutionism. As Larsson argues, in the 1840s Marx was under the impression that, even if industrialisation in most European nations, at best, was only beginning, crisis-prone capitalism had already lost its capacity for developing the productive forces much further. Fifty years later, in 1895, Engels admitted that he and Marx had made that mistaken appraisal.[18] So, Marx’s expectations of proletarian revolution in backward Germany and France did in fact not run counter to his stated view that capitalism must first run its course. Capitalism had run its course! And now that the bourgeoisie had lost its capacity to create the industrial infrastructure necessary for a communist economy, it was only logical for the proletariat to assume that responsibility and take over. “Permanent revolution” did not run counter to Marx’s insights about capitalism and the productive forces; rather, it seems logically to follow from them.[19] As for Marx’s racist views, he and with some different accents Engels too, worked under the assumption that human “races” differ in their inherited talents. Some races possess more excellence than others. Inherited differences in mental make-up between human races supposedly were caused by several factors, such as the soil on which people live; nutrition patterns; hybridisation; and—the Lamarckian hypothesis—adaptation to the environment and the heredity of acquired characteristics. Marx and Engels not infrequently stooped to derogatory and degrading characterisations of nations and races for whom had a low appreciation. Marx’s racism is acknowledged and deplored in the existing literature, but authors tend to read it as a strange anomaly incompatible with Marx’s overall system and, therefore, as an embarrassment rather than a fundamental shortcoming of his thought.[20] This is hard to maintain. As Marx and Engels saw it, systems of production are rooted in certain “natural conditions”—geological, climatic, and so on. Race represents one of these conditions, referring as it does to the quality of the human material. The inherited mental faculties of races, whether excellent or shoddy, help determine whether these races manage to develop their economies successfully. But, crucially, this does not undo or even affect the dependence of “superstructural” phenomena on economic infrastructures. Race is simply not about the relationship between these two great societal spheres. In Marx’s own imagination the race factor added a dimension of understanding to how or if economies come to flourish, but without in any way affecting the deterministic order of his economic materialism, running from the economy to state and political institutions. No incoherence here.[21] Something similar was the case with Marx’s remarkable views about the passions, which I have explored for the early years 1841 to 1846. In my interpretation of the philosophical fragments written in these years, Marx cast humanity as a productive force driven by creative passions: an impassioned productive force. If this reading is correct, this helps us understand why Marx assumed that economic and technological productive forces manifest an inherent tendency to accumulate and improve: it is because we passionately want them to. Conversely, it also helps explain why Marx believed productive stagnation makes revolution inevitable: humanity is too passionate a being to accept being slowed down. Marx’s “materialist” scheme of productive forces and relations of production, then, was predicated upon an essentially psychological hypothesis, a formula of materialised desire and subjectivity.[22] And once again, no incoherence here: the hypothesis of a creative, passionate urge fuelling the productive forces in no way conflicts with the “materialist” assumption of a chain of causation running from stagnating productive forces to the emergence of new relations of production to a new political and ideological order. Marx had remarkable integrative gifts; he was the master of combining the uncombinable. He managed to keep many of his wide-ranging intuitions, running in so many different directions, together in a single frame. Even if that frame often was incomplete and formulated in ramshackle ways, yet he managed to avoid all too glaring inconsistencies and keep a degree of underlying logic intact. Future Marx Does Marx have a future? There is much to suggest that he doesn’t and that the days of his posthumous success are finally over. Whether or not “actually-existing” communism reflected his ideas and ideals, its collapse and discreditation might be impossible for Marx’s ghost to recover from. Some deep processes have further contributed to Marxism’s demise. Marx’s core business was the industrial proletariat and the class struggle. But contrary to his predictions, the manual workers’ share in the industrialised world’s labour force sharply decreased in the second half of the twentieth century. What is more, far from becoming impoverished, the relatively small class of manual workers became spectacularly better off. Newly industrialising countries likely will manifest the same pattern. The new “precariat” of marginal and not well-off workers, often consisting of ethnically-mixed migrant populations, are more difficult to organise than the old proletariat concentrated in large factories. Marxism’s consolidated proletarian basis has, then, largely fallen away. Marxism thrived, too, on national-liberation struggles. National emancipation was an ambition Marx could sympathise with, even if never in a principled way. But he did support German, Italian, Hungarian, Polish, and other struggles for democracy and state independence. Not only class warriors, twentieth-century national-liberation warriors, too, could relate to him. However, with the end of colonialism the heydays of national-liberation wars are now long over. There is an end even to Marx’s scope. Present-day activists have a hard time reconnecting with him. In the new post-modern condition, emancipatory struggles have shifted towards issues of gender, sexual preference, race, ethnicity and religion, and, importantly, the environment—themes Marx’s voluminous works have little if any positive connection with. The new times have at last begun to make the man irrelevant. This is how things look now. But I am not absolutely convinced that Marx is irretrievably on the way out. The structural downsides of capitalism are such that, even if we regard that system as a lesser evil compared to communism, critiques of its downsides will continue to be formulated. Those interested in the more radical critiques of capitalism will unavoidably pick up Marx, still the most radical critic of that system available on the market of ideas. The theory of “surplus value” allows Marx to argue that capitalism exploits wage labour not because of any particularly atrocious excesses but quite irrespective of wage and working conditions. Wage labour is exploitation (and alienation). Marx was all for reforms, but in his book, reforms change nothing in capitalism’s exploitative and alienation-producing nature. That the theoretical basis of this uniquely radical critique of capitalism, the “labour theory of value”, is an empirically untestable, metaphysical construction hardly matters: stranger things have been believed. Whether Marxism will ever make a comeback depends on now unpredictable changing circumstances that would refocus global radical activism to once again target capitalist, rather than, for example, racist or patriarchal structures. Should that happen, Marx’s rediscovery as radical guide is likely. Marx’s ghost is waiting for us in the wings, happy and ready once more to offer us his services. [1] Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (London, New York: Routledge, 2005), 7–9. [2] Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy. The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000 (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), chapter 2. For a similar interpretation, see for example: Gary P. Steenson, After Marx, Before Lenin. Marxism and Socialist Working-Class Parties in Europe, 1884–1914 (London: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991), 20–1. [3] Wolfgang Leonhard, Sowjetideologie heute, vol. 2, Die politischen Lehren (/Frankfurt M., Hamburg: Fischer Bücherei, 1962), 106. [4] Terry Eagleton, Why Marx was Right (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2011), 16; Steve Paxton, Unlearning Marx. Why the Soviet Failure was a Triumph for Marx (Winchester, Washington: Zero Books, 2021), chapter 1. [5] See: Eley, 2002, 40, 509. Though emphasising the significance of the term “dictatorship of the proletariat” in Marx’s work, Hal Draper agrees that that it signified nothing more than “rule of the proletariat”: The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” from Marx to Lenin (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987), 22–7. [6] Michael Löwy, The Politics of Combined and Uneven Development. The Theory of Permanent Revolution (London: Verso, 1981), 189. [7] Ibid., 7–8. [8] Ibid., chapter 1. [9] Reidar Larsson, Theories of Revolution. From Marx to the First Russian Revolution (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1970), 9–11, 24–31. [10] Alvin W. Gouldner, The Two Marxisms. Contradictions and Anomalies in the Development of Theory (London, Basingstoke: MacMillan, 1980). [11] Jonathan Sperber, Karl Marx. A Nineteenth-Century Life (New York, London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2013), introduction. [12] Quentin Skinner (1969), “Meaning and understanding in the history of ideas”, History and Theory, 8(1): 3–53. [13] Terrell Carver, Marx (Cambridge, Medford: Polity Press, 2018). [14] On The German Ideology see: Terrell Carver (2010), “The German Ideology never took place”, History of Political Thought, 31(1): 107–27. [15] For the creation of the Marx cult and “Marxism”: Christina Morina, Die Erfindung des Marxismus. Wie eine Idee die Welt eroberte (München: Siedler, 2017). [16] Erik van Ree (2013), “Marxism as permanent revolution”, History of Political Thought, 34(3), 540–63; “Marx and Engels’s theory of history: making sense of the race factor”, (2019) Journal of Political Ideologies, 24(1), 54–73; (2020) “Productive forces, the passions and natural philosophy: Karl Marx, 1841–1846”, Journal of Political Ideologies, 25(3), 274–93. [17] Erik van Ree, The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin. A Study in Twentieth-Century Revolutionary Patriotism (London, New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002), 282. [18] 1895 introduction to “Class struggles in France”, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, vol. 27, Engels: 1890–95 (New York: International Publishers, 1990), 512. [19] van Ree, 2013. More on the permanent revolution in Marx: Erik van Ree, Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin (London, New York: Routledge, 2015), chapter 5. [20] See for example: Roman Rosdolsky, Engels and the “Nonhistoric” Peoples. The National Question in the Revolution of 1848 (Glasgow: Critique Books, 1986), especially chapter 8; Michael Löwy, Fatherland or Mother Earth? Essays on the National Question (London, Sterling: Pluto Press, 1998), 23–7; Kevin B. Anderson, Marx at the Margins. On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies (Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 52 and passim. [21] See for this argumentat in more detail: van Ree, 2019. [22] See for these conclusions: van Ree, 2020. by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger

Few words still offer a more tantalising, but also frustratingly vague, indication of our contemporary era than “populism”. The statistics speak for themselves: from 1970 to 2010, the number of Anglophone publications containing the term rose from 300 to more than 800, creeping over a thousand in the 2010s[1]. The semantic inflation was not only the result of a growing and emboldened nationalist radical right, however. Instead, the 2010s also saw a specifically left-wing variant of populism gain foothold on European shores. This new group of political contenders took, tacitly or explicitly, their inspiration from previous experiences in the South American continent, of which left populism had long been cast as an exclusive specimen. Where did this sudden upsurge come from?

In addition to cataclysmic crisis management, without doubt the most important thinker in this transfer was the Argentinian philosopher, Ernesto Laclau—light tower to left populists like Podemos, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, and even Syriza. Before he went properly political, Laclau was already a mainstay of academic debates in the 1990s and 2000s. Laclau’s theory of populism—formulated from 1977 to 2012, spanning books such as Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory (1977) to On Populist Reason (2005)—has fascinated a whole generation of scholars dissatisfied by either positivist or mainstream Marxist approaches. To them, Laclau provided a full theory of populism that stands out by its conceptual strength, internal coherence, and direct political appeal. Contrary to many other approaches, there also was intense two-way traffic between his populism theory and its activist uptake by movements, from Latin America (Chavism, Kirchnerism, etc.) to the more recent political experiments in the post-2008 Europe (Podemos, Syriza, La France insoumise, etc.). In the 2010s, this two-way traffic took off in Europe. Laclau’s vision of populism is as short as it is appealing. In his view, ‘populism’ is not an ideology, strategy, or designated worldview. Rather, ‘populism’ is an ever-present ‘political logic’, which tends to unify unfulfilled demands based on shared opposition to a common enemy—elites, castes, classes, parasitical outsiders. Populists condense the space of the social by reducing all oppositions to an antagonistic relation between ‘the people’ and a power bloc, the latter consisting of a politically, economically, and culturally dominant group held responsible for frustrating the demands of the former. To Laclau, the unity of this ‘people’ is always constructed and a given. This construction is both discursive and negative: because there is no pre-given to the ‘people’, cohesion is necessarily achieved through condensation in the figure of a leader—one of the most controversial aspects of Laclau’s theory. Populism, in this perspective, is also bereft of any intrinsic programmatic content. Instead, it only refers to the formal way in which political demands are articulated: those demands, in turn, can be of any type, and can be voiced by extremely disparate groups. For Laclau populism can thus take many forms, ranging from the most progressive to the most reactionary one—both Hitler and Marx have their ‘populist’ moments. Like any grand theory, however, Laclau’s theory has also become subject to two symmetric processes: either dogmatic mutation or automatic rejection. These mirror the treatment of left populism in the public sphere in general. Academics either uncritically endorse these movements as democratically redemptive, or unfairly blame them for jeopardising democratic norms. Increasingly, disciples of the Laclauian approach themselves have express their dissatisfactions vis-à-vis Laclau’s theory and the current state of the field. Save a few exceptions calling for an earnest assessment of its balance sheet[2], however, these critiques—both theoretical and practical—are made from perspectives external to the Laclauian theory (mainly liberalism and Marxism). From the liberal perspective, Laclau’s theory is criticised for its alleged illiberal and authoritarian/plebiscitarian political consequences. Marxists, on the other hand, tend to resist the ‘retreat from class’ that his theory implies[3]. Contrary to these criticisms, we propose an internal assessment. To paraphrase Chantal Mouffe’s famous quip about Carl Schmitt, we can reflect upon left populist theory both ‘with’ and ‘against’ Laclau, submitting his theory to closer scrutiny while sticking to most of its basic assumptions. Four aspects of Laclau’s theory are granted particular scrutiny: the articulation of ‘horizontality’ and ‘verticality’, a deficit of historicity, an excessive formalism and a lack of reflexivity. The first point moves from the abstract to the concrete. For Laclau, any populist ‘people’ needs to be constructed and moulded, something that will have to be done through a central agency—here taken up by the figure of the leader. In the view of ‘horizontal’ theorists, Laclau’s theory of populism supresses the natural spontaneity of groups, disregards their organisational capacity, and always runs the risk of sliding into an autocratic path. On the descriptive side, the central role of the leader encounters many counterexamples across historical and contemporary populist experiences, from the American People’s Party, the farmers’ alliance that shook up US politics at the end of the nineteenth century, to the contemporary Yellow Vests, the recent social upsurge against Emmanuel Macron’s politics in France. On the normative side, left populism does indeed live in the perpetual shadow of a Caesarist derailing—as recently shown in the extremely autocratic management of Podemos and la France insoumise by Pablo Iglesias and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, respectively. Yet, in a context where European parties are losing members and politics is becoming more liquid and impermanent, the importance of leaders to organisations seems to be an obstacle to patient organisation-building and mass mobilisation. In this sense, they tend to encourage rather than decelerate the anti-democratic trends they purport to critique. A second problem in Laclau’s oeuvre is its treatment of historicity. Although Laclau makes recurrent references to historical episodes, his work as a whole consistently suffers from a chronic incapacity to relate his findings to a coherent theory of historical change. The poststructuralist language he takes on leads to a relative randomisation of history, placing him at pains to explain large-scale historical changes. Without falling back on a teleological and deterministic conception of history, it is necessary to pay greater attention to the structural transformations of global capitalism and parliamentary democracy to understand our current ‘populist moment’. The history of the 2010s as the European populist decade can not be understood only through the triptych dislocation-contingency-politicisation but must be replaced within a much broader context: the declining structures of political representation across Western democracies, whose roots, in turn, must be found in the changing political economy of late capitalism. Finally, we claim that Laclau and his disciples lack a properly performative theory of populism. Recent research carried out by Essex School scholars (the current started by Laclau) have compensated for this problem, focusing on the intellectual history of populism as a signifier, and showing the performative effects its use by scholars and politicians can have[4]. These show anti-populist researchers and political actors tend to consolidate the coming of a populist/anti-populist cleavage as a central axis of conflict by endorsing a specific reading of contemporary politics and setting out a terrain of battle that superimposes itself on older ones, such as the left-right distinction. However, Essex School theorists remain surprisingly silent on the thin frontier between description and prescription from a Laclauian perspective, and thus on their own inevitable role in creating the reality they purport to merely describe. Finally, Laclau’s extremely formal definition of populism can easily turn into hypergeneralism. His endorsement of a strictly formal conception of populism creates an inability to account both for the similarities and differences between the left- and right populisms. It then becomes dangerously easy to overstretch the concept ad absurdum and even to depict contemporary anti-populism—such as Macron’s—as a form of populism, simply because of the latter’s antagonistic character towards established political parties, even though this antagonism is rooted in a liberal-technocratic conception of politics. As appealing as this overstretch might look—it rightly grasps that Macron and Mélenchon, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, for instance, have ‘something’ in common—it adds to the confusion around ‘populism’ rather than providing a satisfying answer to it. It also distracts the attention from what really unites these political actors: the fact that their emergence in the French party system represents a moment of political disruption (not necessarily populist) made possible by the decline of traditional, organised party politics. To end on a hopeful note, we propose a renewed approach to populism that builds on Laclau’s strengths while re-embedding them in a more robust analytic framework. Such a reassessment could lead to a more careful balance between a general theory of populism (based on, but not reducible to, Laclau’s political ontology) and the concrete appraisal of its empirical manifestations. We can here deploys the metaphor of an ‘ecosystem’: populism is simply one political species (amongst many) particularly adept at adapting itself to the new environmental setting of our increasingly disorganised democracy. In scientific jargon, Laclau’s ‘populism’ is a bio-indicator: a species which can reveal the quality and nature of the environment, while also depending on it. Only when we take this step back, we claim, can we see the silhouette of populism against the wider democratic canvas. [1] The most prolific schools of thought, besides the Laclauian perspective (C. Mouffe, For a Left Populism, London: Verso, 2018; G. Katsambekis & A. Kioupkiolis (eds.), The Populist Radical Left in Europe, Oxon & New York: Routledge, 2019) have undoubtedly been the approaches to populism as a ‘thin-centred ideology’ (C. Mudde and C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy?, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012; J-W. Müller, What is Populism?, London: Penguin Books, 2016) and as a ‘political style’ (B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism : Performance, Political Style and Representation, Standford : Standford University Press, 2016). [2] For an early criticism of this sort, see B. Arditi, ‘Review essay: populism is hegemony is politics? On Ernesto Laclau’s On Populist Reason’, Constellations, 17(3) (2010), 488–497 and Y. Stavrakakis, ‘Antinomies of formalism: Laclau’s theory of populism and the lessons from religious populism in Greece’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3) (2004), 253–267. Recent initiatives to go beyond theoretical immobilism within the Essex school can be found, for instance, in the special issue of the Journal of Language and Politics edited by Benjamin De Cleen and al. (« Discourse Theory : Ways forward for theory development and research practice », January 2021), as well as in a 15th year anniversary symposium for On Populist Reason, edited by Lasse Thomassen, Theory & Event, vol. 23 (July 2020). [3] Good examples of liberal and marxist critiques of Laclau’s theory can be found respectively in P. Rosanvallon, Le siècle du populisme. Histoire, théorie, critique, Paris : Seuil, 2020 and S. Žižek, « Against the Populist Temptation », Critical Inquiry, 32(3), Spring 2006, 551-574. [4] See for instance: A. Jäger, ‘The Myth of “Populism”’, Jacobin, January 3 2018, available at https://www. jacobinmag.com/2018/01/populism-douglas-hofstadter-donald-trump-democracy; B. De Cleen, J. Glynos and A. Mondon, ‘Critical research on populism: Nine rules of engagement’, Organization, 25(5) (2018), 651; Y. Stavrakakis et al., ‘Populism, anti-populism and crisis’, Contemporary Political Theory, 17(1) (2018), 4–27; B. Moffitt, ‘The Populism/Anti-Populism Divide in Western Europe’, Democratic Theory, 5(2) (2018), 1–16; A. Mondon and J. Glynos, ‘The political logic of populist hype: The case of right-wing populism’s “meteoric rise” and its relation to the status quo’, Populismus Working Papers 4 (2016), 1–20. by Bruno Leipold

Bruno Leipold: This book is the culmination of a long engagement of yours with the German council movement that emerged during the Revolution of 1918-19. You wrote your PhD on Hannah Arendt’s account of council democracy and have also edited two volumes on the subject: Council Democracy: Towards a Democratic Socialist Politics (2018) and, with Gaard Kets, The German Revolution and Political Theory (2019). What is it about the councils that keeps drawing you back to them?