|

27/9/2021 Jean Grave, print culture, and the networks of anarchist transnationalism: An interview with Constance BantmanRead Now by John-Erik Hansson

John-Erik Hansson: Let's start with a few introductory questions. Very broadly, who Jean Grave and why should we study him? What does he stand for? Does the book present a general case for studying minor figures in the history of anarchism, as Jean Grave is no longer necessarily so well known?

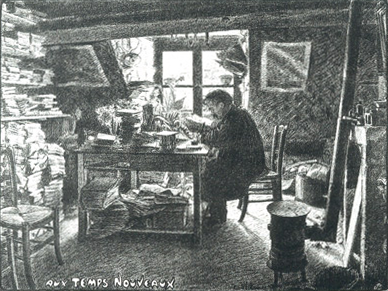

Constance Bantman: Jean Grave was a French anarchist—he was really quite famous until his death in 1939. He was mainly known as the editor of three highly influential anarchist periodicals. First of all, Le Révolté, which was set up in 1879 in Geneva by Peter Kropotkin and a few others, chiefly Elisée Reclus. It was handed over to Grave around the 1883 and he kept it going until 1885, when the paper was relocated to Paris. It was eventually discontinued and relaunched in 1887 as La Révolte, which was forced to close in 1894, in times of really intense anarchist persecution in France. It was relaunched again in 1895 as Les Temps Nouveaux, which more or less ceased business in 1914 when the war started. Grave was also involved in several other publications post-war and until his death. So Grave is primarily known for being a newspaper editor, one might say one of the most influential editors in the global anarchist movement. And he was really quite well known at the time, and was also a theorist in his own right. That's one aspect of his work that completely sank into oblivion. I think you'd really struggle to find anyone reading Grave nowadays. There might be somebody popping up on social media every now and then, but that's about it! But at the time, he was a really influential theorist of anarchism, not quite on par with Kropotkin or say Malatesta or Reclus, but people did read him. His work was translated into numerous languages and published in multiple editions. He was a theorist of anarchist communism very broadly speaking. He was interested in education, and educationalism. It's hard to assess the specificity of his work, really. I would say educationalism within the broader anarchist communist framework was important. He was quite critical of syndicalism, and he was, as we’ll discuss later, pro Entente during the war. He is worth studying not only because he was influential person, but also because of his remarkably long career in anarchism. He became a politicised at the time of the Paris Commune, when he was a teenager. I think his father was quite political and the young Grave was distantly involved in the commune—he was 17 at the time. By the late 1870s, he was politically active, and he never stopped until his death. His long political career mirrors the history of French and international anarchism, and the place of anarchism within the French Third Republic. Grave wrote his autobiography with the title Quarante Ans de Propagande Anarchiste [Forty Years of Anarchist Propaganda], and when I wrote the book, I was thinking, “maybe I could call it Seventy Years of Anarchist Propaganda?”, because that's more accurate. Grave was being quite humble. Concerning your question about the relevance of studying minor figures, I think there is something interesting in resurrecting figures who have fallen from grace—Grave especially because of his position during World War One. But I think Grave was an intermediary, not quite a minor figure, because he was so well known and the time. These intermediaries, who were really close to highly influential historical figures, allow us to get new historical insights into figures like a Kropotkin, who was a really close friend of his, or Reclus, with whom he sparred quite a lot. They also allow us to piece back together the social history of anarchism, to shed light on the history of ideas in many different ways, and to reflect on more canonical history as well. JEH: Your book is a biography of Grave but it's also a biography of his periodicals, especially La Révolte and Les Temps Nouveaux. What led you to that focus? What brought you to take that angle on Grave and on anarchism more generally? CB: That's also related to your first question—which was “why study Grave?”. One of the main drivers of my study was a reflection on the concept of anarchist transnationalism, which I’ve been interested in for a long time, like many historians have. My work to date was focused on exile and I was absolutely fascinated with Grave who pretty much never left Paris at a time of intense anarchist forced mobility. Lots of French anarchists went into exile and there was a great deal of labour migration. But Grave was pretty much always in Paris, and yet, he was everywhere. If syndicalism was being discussed in Latin America, you could be sure that Grave would be part of that conversation. Same in Japan, same in discussions of political violence in the UK, where there were many French anarchists. What I realised is that Grave presents us with what we might call an example of immobile or rooted transnationalism and the fact that it was absolutely fine or feasible for somebody to be sedentary and to stay in Paris whilst having global influence. The reason for this, what solves the problem, is print culture and the mobility of print in this period. So that's how I came to be interested in the papers, because they were agents of circulation of mobility. As Pierre-Yves Saunier, an influential historian of transnationalism, wrote, for the international circulation of ideas to happen, you don't necessarily need personal mobility, you need connectors. The papers were the great connectors. In addition to that, the papers are absolutely fascinating. They are remarkable cultural documents, because one of Grave’s salient features was that he was connected with so many writers and visual artists. He was really adept at enlisting the support for the movement, and the papers really reflect that. The papers had a supplément littéraire, which was sometimes illustrated and many illustrations were sold for charity purposes, alongside the paper, by artists who are nowadays extremely famous for some of them (for instance Grave’s friend Paul Signac), or by illustrators. So there was this really lush visual and literary culture associated with the papers, which was just pleasant to study as well. JEH: This is a great segue into the next set of questions. You’ve emphasised the importance of print culture throughout the book and in your answers up to now. So, how would you characterise the relationship between anarchism and print culture in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries? CB: Well, I’ve thought about this a lot, and I think I would use the term symbiotic. I think it was a very symbiotic relationship, they fed off and into each other. There are many ways in which this imbrication of anarchism with print culture functioned. A few examples: print culture existed through periodicals, in particular, but also pamphlets which were sold and printed separately. All of these were the sites where anarchist ideology was elaborated and constructed dialogically. These publications were fora, there was a great deal of discussions within and around the papers and other publications. Print culture was the prime place of ideological elaboration. It was also the key place for the dissemination of ideology. We've discussed illustrations—and Grave’s papers were famously very dry, very theoretical—but if we think of papers like the Père Peinard, a really engaging contemporary publication, there was a language, there was also a visual style, which was incredibly effective in conveying very complex, occasionally dry ideas to their target audiences. So that's another aspect in this relationship between anarchism and print culture. Because, precisely, there was no party framework, the press was the main forum. Another aspect is also that the press and owning anarchist print was regarded by the authorities as the ultimate sign of anarchist belonging. This was very much acknowledged that the time, and this was a way of self-identification as well. The historian Jean Maitron has written extensively about anarchist being a very bookish culture in this respect, and this notion of print ownership as a sign of anarchist belonging is striking when you look at police records. This idea that owning and reading anarchist material was a sign of being an anarchist is really important. Print culture had other functions as well. For instance, I've mentioned the global influence of Grave, it was also through the press that anarchism was developed as a global movement. The press also facilitated the daily organisation of anarchist circles, connecting activists with one another. So, there are so many practical, organisational, ideological and cultural ways in which print culture made anarchism possible. In return, anarchism fostered this absolutely remarkable print culture, which is one of our main sources today in documenting the history of the movement. JEH: When I was reading the book, I was fascinated by the discussion of the formation of an anarchist identity alongside that of an anarchist ideology. I was wondering if you could comment, a little bit about the kind of dynamics of the relationship between the formation of an anarchist identity and at the same time, the formation of an anarchist ideology. CB: Yes, I think that's such an interesting approach, because at the moment the great buzzword among historians of anarchism is “communities”, which makes me think that this notion of anarchist identity is somewhat under-explored. Paradoxically, we tend to think about anarchist identity through the collective prism of community and they’re not quite the same thing. Of course, the biography is a good entry way into these questions. Grave was somebody who was interested in ideas, but being an anarchist was a praxis as well. It was about taking part in gatherings in ‘Cercles’ or local groups, it was very much a sociability; it fed on this social identity and that's how it developed in the aftermath of the Second Industrial Revolution. Grave’s own itinerary shows that anarchism was very much a place where new identities, individual and collective, were created. It's been a matter of debate, to what extent anarchists actually identified with the ideology or recognised it, or were well versed in it. For many people, it was more practical—if we think about the many sorts of petty criminals that the police identified as anarchist were probably not particularly familiar with Kropotkin’s ideas or say Stirner’s, but to somebody like Grave, Kropotkin—and more generally, ideas and theories—were, of course, very important. JEH: To continue at the intersection of identity and ideology, bringing print culture back in, one of the things that struck me when I was reading your book is how you show the way in which different editors of anarchist papers interacted with and responded to one another. There is this debate between Jean Grave and Benjamin Tucker taking place throughout the pages of Liberty and La Révolte—mirroring the broader debate between anarchist individualists and anarchist communists. Yet, they maintained a veneer of unity as anarchists and actively sought to continue collaborating. This seems to have been common, especially before 1900, but it that changes over time, and you are able to track the subsequent process of ideological reconfiguration and division. So, I was wondering, firstly, what you thought this could tell us about anarchism at the time, and secondly, why you think things changed in the early 20th century. CB: It's a striking story to follow. What we can see with anarchism, in particular through periodicals in the 1880s, is the case of an ideology emerging and constituting itself as a social movement. There is a sense of shared identity and affinities between, say Tucker and Grave—occasionally there are bitter fallouts, but still the sense of commonality of interests, for instance in the face of repression, is quite important. In the late 1890s, post ‘propaganda by the deed’, it's quite established that there is a transition, which Jean Maitron has called “la dispersion des tendances” [the scattering of tendencies]. We can see that things become a bit more ideologically polarised especially, I think, because of the advent of new brands of anarchist individualism and lifestyle experiments which more conservative anarchists like Grave were horrified by. Vegetarianism, women's emancipation, free love colonies—all that was an absolute nightmare for them. And then you have les gueulards [the loudmouths] of La Guerre Sociale who also have a lot of misgivings and hostility towards figures, especially like Grave, who claim to have so much power and ascendancy in the movement. At this stage, it becomes quite fixed and this feeling of unity dissolves. Then the war exposes deep ideological rifts. I’ve never quite thought of it in those terms, but it’s also absolutely striking to see such a condensed history of a highly influential social movement from emergence, unity, to the shattering blows of the First World War. JEH: And in this way, I think what you show in the book is how periodicals help us track and reflect on these processes of ideological formation ideological differentiation which take place in a very short amount of time. Anarchism, then, can be seen as a microcosm for the study of ideological differentiation more broadly. CB: Absolutely, that is really interesting. There’d have to be a comparative study to really identify the specificities of anarchist print culture. In the case of anarchism, the main ideological debates play out in major periodicals. The doctrine of syndicalism was elaborated, if you look at Europe, in the dialogue between a number of publications: Freedom in London, Le Père Peinard and then La Sociale when Pouget comes back to Paris, La Révolte, Les Temps Nouveaux, the Italian publications coming out in London, Italy, and the US at the same time. These debates and discussions unfold the big theoretical pieces as well as pamphlets, but what is also interesting is how it plays out in the paratextual elements of the periodicals—in one footnote you might find a commentary, or the report of a meeting where these questions were also being discussed I find that one of the joys of studying that press is how they argue with each other. Conflicts between Grave and, say, Émile Armand (L’Anarchie) were such that they could be really vile with each other, and it could go on for weeks—the squabbling and the pettiness and “you said that…” and “the spy in London was doing this…”, all of which might be echoed by placards and manifestoes… These are arguments reflected in various elements of print culture to which we might not necessarily pay attention, but which were really important in this process of differentiation. JEH: Thinking about another dimension of anarchism and thinking about Grave’s practice as an editor and publisher. In anarchism it's common to say that prefiguration, prefigurative politics are central. Anarchists want to enact the kinds of social relations they would like to see in a revolutionary future as much as possible in their day to day lives. How do Jean Grave and his publications fit that? How does he enact—or does he enact—the kind of anarchist relations that presumably he would have wanted to see in a revolutionary society? CB: That's a very problematic area for Grave. The papers were notorious—perhaps unfairly so—for being places where Grave shared his point of view, and allowed people with whom he agreed to share their point of view. So, you might say, if we go with a prefigurative hypothesis, that his vision of an anarchist society was very much ‘everybody does what Grave has said should be done’. He was infamously nicknamed the Pope on rue Mouffetard [the place where his publications were printed] by the anarchist Charles Malato, in reference to this alleged dogmatism. That’s one aspect which I’ve tried to correct in the book. The papers were actually quite collective, collaborative endeavours. I've mentioned syndicalism and Grave’s defiance toward syndicalism, and yet the pro-syndicalism anarchist and labour activist Paul Delesalle had a syndicalist column there for a very long time, and Grave really engaged with it. More broadly, if we look at some of his archives, his letters, he did reject some material submitted to the paper. For the literary supplement, I remember one letter where he says “I can’t publish this, the quality of the verse is insufferable, I’m not going to publish this!”. He was also prone to excommunication and personal quarrels but in the broader milieu of anarchism this was not specific to Grave. When things soured, relationships could become quite embittered and then individuals would be kicked out of groups… But I don't think Grave was necessarily as intolerant of personal and ideological difference as he's been portrayed. As I’ve mentioned, the papers were dialogic spaces: there were letters, and I must really emphasise again the paratextual elements, which allowed many voices and different currents into the paper. The last two pages were announcements for local meetings, book reviews written by different people… The contributions are very dialogic in that space, and I think that's one of the reasons why there was successful—and this was very much a deliberate approach on Grave’s part. And another aspect of this is the place where the papers were produced: his attic in the Rue Mouffetard. That was famously really, very open, including to spy infiltration. There was a limit to how many people could be there, because the attic was really small, but this was a very open space. There are so many stories shared by Grave or others of intruders, spies trying to infiltrate this space, there was a bit of dark tourism around it, but so many contemporary commentators stressed the openness of this place, and it seems clear that this shows a certain pedagogical outlook on what anarchism should be, and how important dialogue was to its construction. JEH: And I suppose it also fits in with the discussion about anarchist identity and what it meant to be an anarchist publisher in that in that period. Moving on to the theme of personal connections. One of the things that seems to be key to your study of anarchism through Jean Grave is the way in which his personal connections as well as his material position—his work, his way of working and his networks—made it possible for him to not only be a theorist of anarchism, but also a kind of unavoidable character at the time in the reconfiguration of anarchism in the late 19th and early 20th century. How important do you think investigating networks of personal relations is to the study of anarchism specifically or political ideologies more broadly? CB: I think it is really important. To take the example of Grave, one obvious aspect which has been under-explored is his friendship with Kropotkin, although there is a good deal of social history around Kropotkin at the moment—it’s the centenary of his passing. But looking at networks really allows us to show different sides of the movement and its protagonists, and the great deal of dialogue and collaboration that existed in anarchism. This is not specific to my research. Fairly recently, Iain McKay has studied how important these French periodicals were for the dissemination and elaboration of Kropotkin’s ideas.[1] So, if you bypass the friendship with Grave and the editorial partnership, which was so central and completely ignored until a few years ago, you really do miss on a really important aspect of the creation and diffusion of anarchist communism. It’s the same between Grave and Reclus: looking at egodocuments and less formal sources (typically letters and autobiographies), you can uncover many arguments about violence, and also debates about ivory tower anarchism, of which Grave was repeatedly accused. These seemingly casual discussions and letter exchanges shed light on the big debates which form the more official intellectual and political history of anarchism. With Grave, I became really interested in the course of my research in his second wife, Mabel Holland Grave. She was an absolutely fascinating character in the anarchist movement, in the fine British tradition of upper middle-class women’s anarchism. She comes a bit out of nowhere, after Kropotkin introduced them, with no clear journey to anarchism, for instance. She came from a very affluent background, was boarding-school educated, which was not necessarily a given even for a privileged woman in this period, and she became a regular partner of Grave, both personally and politically. She collaborated with him and contributed to the paper. Anarcha-feminism was not something Grave really engaged with at all, but then we look at the praxis and the way he dedicated a book to her, stressing that they’d worked on it together, for instance, the fact that she was clearly a partner and the beautiful illustrations which she contributed, along with her editorial input… You could say that’s even worse: he used and silenced the labour of his wife. However, that's not the way I interpreted it. I thought that it was interesting how, in his daily life, so if we talk about prefiguration, he seems to have been far more progressive than his writings might have let on. So, I do think these networks are crucial. And here I'm really talking about private life—but there are so many ways you can look at this: friendship, casual acquaintances… I loved reading Grave’s memoir, how he wrote about bumping into people in the street—activists he knew, anarchist or not—and how they would discuss this or that. That's the daily life of a social movement. And I think for anarchism this is so important. If you're looking at a movement—perhaps like Marxism, where the doctrine is elaborated in conferences, basically where there is a sense of strict sense of orthodoxy, where there are formal institutions at various levels and gatekeepers often occupying official roles, it's far more problematic. The same was probably true of the socialist parties emerging at the time. This is about the frameworks of political creation and channels of political dissemination. Anarchists did not have parties, and rarely had binding official documents. And so this allowed that kind of flexibility, whereby informal interactions become essential. For historians, this means that the social history of politics is immediately essential. This is true of any political movement, of course, but the because of the predominantly (an-)organisational character of anarchism, the social milieu is more obviously relevant. JEH: This is nicely tied to the next question I wanted to ask, which returns to prefigurative politics and the way in which personal connections and networks are linked to prefiguration. As you show, it's these networks and personal connections that put Grave on the map. It's because he is able to create and foster these connections that he is a key figure in late 19th-century anarchism. How does this role as a kind of rhizome, as a node in the network sit with anarchist politics? Does it lead to the kind of problems you were talking about, like gatekeeping? How does it fit with anarchism’s argument in favour decentralisation and the diffusion of power? CB: Yes, that's a very problematic point and is one of the things I really set out to investigate with the book. I've come to the perhaps generous conclusion that Grave was primarily genuinely interested in sharing knowledge and sharing anarchist ideas—sharing his own vision, one might say, but I don't think that's necessarily true. I think really the emphasis for him was on enabling discussion and spreading anarchist communism. I have come across discussions with Kropotkin where he says, “have you seen the number of ads we have in the paper this week?”, and that’s of course not commercial advertising but ads where people communicate and share information about local organisations. That was on the national scale, and Grave would also advertise meetings internationally. Grave was conscious of the authoritarian potential of centrality. He was definitely aware of the criticism that was levelled at him, and he does say this autobiography: “I did this because, basically, I was quite certain of what I was saying, and I had my vision and the paper had a special place in the global anarchist movement…”, that was his argument in upholding what might be considered a very dogmatic approach to anarchism and its daily politics. But, alongside this, and there was so much effort towards diffusion, toward sharing the paper, reporting on and encouraging local movements. The suspicion levelled at Grave, that he was focused on spreading his own, somewhat narrow conception of anarchism is obviously what we would call know diffusionism—this idea that French anarchism shone all over the world, from Paris, from the attic on the rue Mouffetard, and occasionally from London but that's about it. But there are discussions, in particular from Max Nettlau, that are absolutely staggering in how contemporary they sound in their critique of such diffusionist assumptions. There are records of Nettlau expressing that “sending a few dozen copies of La Révolte to Brazil is not going to bring about revolution in Brazil, you need to adjust your ideas a little…”. He was quite aware that sharing print material was not enough, and was also fraught with ideological assumptions. However, what is interestingly being discussed by historians of anarchism working on non-European areas—I'm thinking of Brazil and Asia, in particular—is the great effort that went into and adapting anarchist material to local circumstances. You can see from Grave and others that there was a great deal of effort spent in seeking information about international movements, to reflect their activities in the paper, but also to have the knowledge to discuss their situations. I think it's far more nuanced and horizontal vision that appears. This is really interesting for us, as contemporary historians looking at these circulations in the light of all the discussions about provincialising Europe, and I would say the anarchists didn't do too badly actually. JEH: Indeed, one of the other points that struck me when reading your book was how you seek to challenge the diffusionist narrative even as you focus on a Paris-based node for the circulation of anarchism. Do you think that the study of someone like Grave and his periodicals—who are, as you’ve said, connectors—and of anarchist print culture, more generally, may lead us to rethink the way in which anarchism circulated and reconfigured itself at the transnational and global levels? How can studying anarchist print culture help us provincialise Europe and European anarchism? CB: What is really great at the moment is that there are so many studies from a non-European perspective, discussing all of this. I'm thinking, for instance of and Nadine Willems’s work on Japanese anarchism and Ishikawa Sanshirō, but also Laura Galián’s work on anarchism in a range of (post-)colonial contexts in the South of the Mediterranean[2]. This is really fascinating work in showing different anarchist traditions, exploring new areas, showing how they've engaged with these European movements, but also questioning the very notion of anarchism. Of course, when French anarchism is exported, say to Argentina, where a book by Grave might be translated, its meaning changes automatically through this change of context. So, the more empirical data we have, the more studies we have, then the more we can start revising and understanding what happens in translation, and in a variety of cultural contexts. Print culture is a very good way of entering this because print was the prime medium for the global circulation of anarchism. And if you had people being mobile, they would set up or import papers, most of the time, so print culture is probably the best source that we have to study this. This also includes translations of major theoretical works and the international sale of pamphlets—these aspects are less well-known, for now at least, but can really help us understanding processes of local appropriation. [1] Iain McKay, "Kropotkin, Woodcock and Les Temps Nouveaux", Anarchist Studies 23(1) (2015), 62ff. [2] Nadine Willems, Ishikawa Sanshirō's Geographical Imagination: Transnational Anarchism and the Reconfiguration of Everyday Life in Early Twentieth-Century Japan (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020); Laura Galián, Colonialism, Transnationalism, and Anarchism in the South of the Mediterranean, (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). by Waqar H. Zaidi

If you were to ask someone about the drivers of globalisation, you would probably be told that it is caused by faster, greater, and more accessible transport and communications. These have allowed for greater international travel, faster movement of people and information, and the greater circulation of trade, commerce, and capital more generally. Questioning further, you will learn that the speeding up and spread of transport and communications have in turn been driven by transformative new inventions: most recently the internet, but going backwards in time: the aeroplane, the telephone, the steam-ship, and the telegraph.

Such ideas are so deeply embedded in our consciousness that there is little questioning them. But what if they could be questioned: problematised, analysed, historicised? That’s exactly what historians have begun to do. One line of enquiry has been to examine culture and boosterism in relation to particular technologies as they emerged and spread at particular time periods. By technological culture I mean widespread assumptions and beliefs about particular technologies and technological spectacles. By technological boosterism I mean publicity and rhetoric specifically created to boost these technologies and their positive impact. Important case studies of this ilk include studies of the telegraph in the late 19th century and aviation in the first half of the twentieth century.[1] But what if we could go further, and see these types of beliefs as ideological: that is as part of wider political ideologies, or cohesive enough to be considered as ideologies in and within themselves? In my new book, Technological Internationalism and World Order: Aviation, Atomic Energy, and the Search for International Peace, 1920–1950, I do exactly that. I argue that aviation and atomic energy were seen by liberal internationalists as internationalising technologies, and were incorporated into both their political projects for political transformation at the transnational level, and their beliefs about the nature of international relations.[2] The book explores US and British proposals for the international control of aviation between 1920 and 1945, and proposals for the international control of atomic energy in 1946. These proposals, I suggest, need to be seen not only as attempts at arms control (which they undoubtedly were) but also as parts of wider ideologies seeking to remake international relations, and as manifestations of internationalising beliefs about various sciences, technologies, and technical experts. These proposals, I suggest, point to a wider technological internationalism that was not only prominent amongst intellectuals and practice at the time but also more widely distributed in society. This technological internationalism was not uniform in its characteristics, and nor was it unchanging: rather it was heterogeneous, waxed and waned over time, and focused on different technologies and techniques at different points in time. The period 1920 to 1950 was a tumultuous time socially and politically, with ideas and discourses also emerging, changing, and/or dissipating. It is no surprise, then, that technological internationalism was also subject to the same push and pull of domestic and international politics, as well as social, economic, and technological transformations. Yet it retained an essential unity in terms of core beliefs and commitments. What, then, is technological internationalism, and where might we find it? What’s to be gained by introducing this concept, and what aspects of our world might it allow us to understand better? Two terms currently used by historians shed light on how this notion might function: scientific internationalism and technological nationalism. Scientific internationalism is usually seen as both an activity and an underlying ethos: the activity being scientific cooperation across national boundaries with little regard for political and cultural differences, and the ethos behind it the notion that science as an unhindered knowledge-producing activity is, and should be, inherently international. Scientists, as carriers of scientific internationalism, are said to embody this ethos.[3] Technological nationalism is also both an activity and an ethos, though is generally located in the policymaking sphere, and understood to be the pursual of national technological projects for prestige rather than economic or other rational reasons. It usually includes an ascription to particular technologies of qualities linked to the nation and national prestige.[4] So, for example, in my study of the celebrated British engineer Barnes Wallis I showed that he ascribed aerial qualities to the English nation, and in turn saw his aeroplane designs as peculiarly English.[5] Technological internationalism, I suggest, is akin to both. Like technological nationalism it focuses on particular technologies, inserts them into historical narratives, and ascribes to them particular transformative properties. More than just artifacts, these technologies are political in that they are thought to naturally achieve, or have the potential to achieve, particular social and political outcomes. Like the science in scientific internationalism, the technology in technological internationalism also helps (so it is believed) to bring people together by transcending national boundaries and political differences. The attribution of internationalising abilities to technologies first emerged most forcefully in the 19th century as part of a wider attribution of internationalising attributes to international trade and commerce. As the argument that free trade and commerce brought countries together and so spread peace started to spread, boosters of particular new technologies promoted them through these ideas. So, for example, the telegraph was touted as a great internationalising technology bringing the nations of the world together.[6] Similarly the steamship drove hopes for a closer integration of the British empire and English-speaking peoples.[7] As a ‘new internationalism’ spread in the first two decades of the twentieth century, so did the roster of technologies with these Cobdenite properties.[8] For internationalist Norman Angell, writing just before the First World War, the steam engine and the telegraph were now joined by the railway, printing, and electricity in deepening interdependence. War, he concluded, was an increasingly irrational choice for nations whose commercial interests were so globally intertwined.[9] These lists of technologies kept pace with the latest inventions in transport and communications. By the 1920s it was aviation which was seen as the leading world-changing technology. Radio was soon added too. One list, published by internationalist legal scholar Clyde Eagleton in 1932 read: ‘steam and electronic railways and ships, telegraphs and telephone, newspapers, and now aviation, radio, and moving pictures’.[10] Technological internationalism consequently emerged as an important component in liberal internationalist rhetoric and imagination because the artifacts that it placed at its center both encapsulated some of the central tenants of liberal internationalism and made them accessible to a wider public. Indeed, by talking about internationalist projects through technologies activists reflected back many society-wide assumptions about these technologies and the world more broadly. It was widely accepted that the aeroplane was ‘making the world smaller’ or ‘bringing people together’. Through technological internationalism internationalists could connect their calls for an international society or greater international organisation to such public ideas. The interwar years, incubators of extreme ideologies and movements, produced radical liberal internationalisms which incorporated such technological internationalisms.[11] These technological internationalisms functioned on two registers in liberal internationalist activist and intellectual output in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. The first, noted above, connected straightforwardly to widely held notions of communications and transport-driven international connectivity. The second consisted of particular political proposals for the international governance of technology in the public sphere. These built on and amplified ideas about the inherently pacifying effects of technologies and the perverting nature of militarism, but developed them towards radical proposals that spoke to liberal internationalist agendas on arms control and collective security. Building on the emergent liberal internationalism of the period (including earlier calls for international naval policing and international organisation), these proposals emerged in Europe after the First World War in the form of calls for the formation of an international police force. This was to consist largely or solely of military aircraft, and was supposed to create collective security by enforcing peace and disarmament. These proposals expanded further during the 1932 Geneva disarmament conference, at which European delegates discussed proposals for the internationalisation of civil aviation as well. Both military and civil aviation, it was argued, needed to be taken out of the control of nation-states and instead controlled by the League. In most proposals nation-states were to retain fighters and small transport aircraft only, with bombers and civilian airliners being handed to the League to create a League air force and airline. Once the disarmament conference collapsed, and rearmament accelerated into the latter half of the 1930s, hopes for internationalised aviation dwindled, but were rekindled during the Second World War. A United Nations air force was widely discussed in US and British internationalist policymaking and internationalist circles (prominent proponents included James T. Shotwell and Quincy Wright in the US, and Philip Noel-Baker in Britain), and even raised at the 1944 Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the formation of a United Nations organisation. Although no air force was formed, the finalised Charter of the organisation retained some scope for its organisation. Although these proposals were sustained by a number of social processes, they were also founded on a number of particular beliefs about the nature of science and technology. First, it was believed that modern science-based technologies, such as aviation, were inherently civilian with the potential for great positive impact, but could be, and often were, perverted for militaristic and nationalist ends. Human thinking and institutions were not advanced enough to understand or cope with these negative effects, and so needed to be developed further in an internationalist direction. In August 1945 a powerful new technology was introduced to the world, atomic energy, which clearly had the potential for great destruction but also promised (so it was believed) cheap energy and other benefits. The internationalist impulse towards international organisation was rejuvenated, though atomic energy now replaced aviation as the great transformative technology in world affairs. The foundational beliefs about the nature of science and technology continued, transferred now from aviation to atomic energy, and from the League of Nations to the United Nations. Internationalists turned to call for the transfer of atomic plant and equipment from the control of nation-states to international organisations, and official proposals (such as the Baruch Plan) were tabled and discussed at the United Nations. It ‘seems inescapable’, announced Manhattan Project physical chemist Harold Urey at a major internationalist conference in 1946, ‘that within a relatively short time a world government must be established if we are to avoid the major catastrophe of a Third World War’.[12] Although these visions and proposals did not come to pass, and liberal internationalism declined in fervor as the Cold War deepened, notions of communications and transport-driven international connectivity survived. It is still commonplace to hear today that the aeroplane, alongside newer inventions such as the internet, is shrinking the world.[13] But perhaps the aeroplane, the internet, and other technologies have indeed shrunk the world, and brought about greater globalisation and globalised interactions. If this is so, what benefit do we gain by marking these beliefs as ideological, rather than as common sensical commentary on reality? My book suggests that many such beliefs about these technologies go far beyond simple shrinkage. They focus on the implications of shrinkage, which are generally taken to mean a heightened possibility of both peace and war. These beliefs are thus inherently politically, and allow these technologies to be referenced in or be incorporated as touchstones of political programs or rhetoric that promise international peace and the abolition of war. Today, the integrationist properties of modern technologies such as the aeroplane and the internet are so widely taken for granted that they are often assumed rather than explicitly stated, and are sometimes even seen as cliched. Yet challenges to technological internationalist assumptions have emerged over the years, especially as the allure of globalisation wore off in the 2000s and people turned to question the meaning and benefits of global integration. More recently, we have discovered that the internet can just as easily spread disinformation, hate, and fear as it can spread understanding. So we continue to grapple today with the questions to which technological internationalists once thought they had the answer: what are the inherent potentials of new technologies, and how can they be use to bring about our utopias and avoid our nightmares. The answers to these questions, I would suggest, are more ideological than one might care to admit. [1] Simone M. Müller, Wiring the World: The Social and Cultural Creation of Global Telegraph Networks (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); David Edgerton, England and the Aeroplane: Militarism, Modernity and Machines, 2nd ed. (London: Penguin, 2013); Robert Wohl, The Spectacle of Flight: Aviation and the Western Imagination, 1920-1950 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005); Jenifer Van Vleck, Empire of the Air: Aviation and the American Ascendancy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013); Joseph J. Corn, The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation, 1900–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983). [2] Waqar Zaidi, Technological Internationalism and World Order: Aviation, Atomic Energy, and the Search for International Peace, 1920–1950 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021). [3] There is a large literature on scientific internationalism, for an overview see: Brigitte Schroeder-Gudehus, ‘Nationalism and Internationalism’, in R.C. Olby, G.N. Cantor, J.R.R. Christie, and M.J.S. Hodge (eds.), Companion to the History of Modern Science (London: Routledge, 1990), 909-919. [4] The term was coined in the seminal paper: Maurice Charland, ‘Technological Nationalism’, Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory X 1-2 (1986): 196-212. [5] Waqar Zaidi, ‘The Janus-face of Techno-nationalism: Barnes Wallis and the ‘Strength of England’’, Technology and Culture 49,1 (January 2008): 62-88. [6] Müller, Wiring the World), chapter 3. [7] Duncan Bell, ‘Dissolving Distance: Technology, Space, and Empire in British Political Thought, 1770–1900’, The Journal of Modern History 77,3 (September 2005): 523–562. [8] Following from the nineteenth-century liberal intellectual Richard Cobden, Cobdenism was a commitment to international free trade and commerce as an antidote to war. Peter Cain, ‘Capitalism, War and Internationalism in the Thought of Richard Cobden’, British Journal of International Studies 5,3 (1979): 229-47. [9] Norman Angell, The Great Illusion: A Study of the Relation of Military Power to National Advantage, 4th ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1913), 142, 277. [10] Clyde Eagleton, International Government (New York: Ronald Press, 1932), 10. [11] I take liberal internationalism to mean, broadly, a belief in a community of nations and a commitment to peace and international order through international trade, commerce, and organisation. See for example: Fred Halliday, ‘Three Concepts of Internationalism’, International Affairs 64,2 (Spring, 1988): 187-198. [12] Harold C. Urey, ‘Atomic Energy, Master or Servant?’, World Affairs 109,2 (June 1946): 99–108. [13] On the internet, see for example the work of historian and social theorist Mark Poster. E.g. Mark Poster, ‘National Identities and Communications Technologies’, The Information Society 15,4 (1999): 235-240. 13/9/2021 'We are going to have to imagine our way out of this!': Utopian thinking and acting in the climate emergencyRead Now by Mathias Thaler

In the public debate, the climate emergency has broadly given rise to two opposing reactions: either resignation, grief, and depression in the face of the Anthropocene’s most devastating impacts[1]; or a self-assured, hubristic faith in the miraculous capacity of science and technology to save our species from itself.[2]

But, as Donna Haraway forcefully asserts, neither of these reactions, relatable as they are, will get us very far.[3] What is called for instead is a sober reckoning with the existential obstacles lying ahead; a reckoning that still leaves space for the “educated hope”[4] that our planetary future is not yet foreordained. To accomplish these twin goals, utopian thinking and acting are paramount.[5] What could be the place of utopias in dealing with the climate emergency? To answer this question, we first have to clear up a widespread misunderstanding about the basic purpose of utopianism. Many will suspect that the utopian imagination appears, in fact, uniquely unsuited for illuminating the perplexing realities of a climate-changed world. On this view, utopianism amounts to the kind of escapism we urgently need to eschew, if we are serious about facing up to the momentous challenges the present has in store for us. Indulging in blue-sky thinking when the planet is literally on fire might be seen as the ultimate sign of our species’ pathological predilection for self-delusion. The charge that utopias construct alluring alternatives in great detail, without, however, explaining how we might get there, possesses an impressive pedigree in the history of ideas. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels excoriated the so-called utopian socialists for being supremely naïve when they paid scant attention to the role that the revolutionary subject—the proletariat—would have to play in forcing the transition to communism.[6] It is important to remark that the authors of the Communist Manifesto did not take issue with the glorious ideal that the utopian socialists venerated, quite to the contrary. Their concern was rather that focusing on the wished-for end point in history alone would be deleterious from the point of view of a truly radical politics, for we should not merely conjure what social form might replace the current order, but outline the concrete steps that need to be taken to transform the untenable status quo of capitalism. Marx and Engels were, to some degree, right. There are many types of utopian vision that serve nothing but consolation, trying to render an agonising situation more bearable by magically transporting the readers into a wonderous, bright future. These utopias typically present us with perfect and static images of what is to come. As such, they leave not only the pivotal issue of transition untouched, they also restrict the freedom of those summoned to imaginatively dwell in this brave new world—an objection levelled against utopianism by liberals of various stripes, from Karl Popper to Raymond Aron and Judith Shklar.[7] Yet, not all utopias fail to reflect on what ought to be practically done to overcome the existential obstacles of the current moment. Non-perfectionist utopias are apprehensive about both the promise and the peril of social dreaming.[8] In the words of the late French philosopher Miguel Abensour, their goal consists in educating our desire for other ways of being and living.[9] This wide framing allows for the observation of a great variety of utopias within and across three dimensions of thinking and acting: theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, as paradigmatically enacted in intentional communities.[10] The interpretive shortcut that critics of utopianism take is that they conceive of this education purely in terms of conjuring perfect and static images of other worlds. However, utopianism’s pedagogical interventions can follow different routes as well.[11] From the 1970s onwards, science fiction writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Marge Piercy and Octavia Butler started to build into their visions of the future modes of critically interrogating the collective wish to become otherwise.[12] Doubt and conflict are ubiquitous in their complex narratives. Social dreaming of this type turns out to be the opposite of escapism: as a self-reflective endeavour, it remains part and parcel of any radical politics worth its salt.[13] The education of our desire for alternative ways of being and living amounts to an intrinsically uncertain enterprise, always at risk of going awry, of collapsing into totalitarian oppression. There is, hence, no getting away from the fact that utopias can have problematic effects. But this does not mean we should jettison them altogether. The risks of not engaging in social dreaming far outweigh its obvious benefits: any attempt to cling to business as usual, at this moment of utmost emergency, will surely trigger an ever more catastrophic breakdown of the planetary condition, as the latest IPCC draft report into various climate scenarios unambiguously establishes. The path forward, then, entails acknowledging the eminent dangers in all efforts to conjure alternatives; dangers that can be negotiated and accommodated via theory-building, storytelling, and shared practices of world-making, but never fully eliminated. This insight is aptly expressed in Kim Stanley Robinson’s work: "Must redefine utopia. It isn’t the perfect end-product of our wishes, define it so and it deserves the scorn of those who sneer when they hear the word. No. Utopia is the process of making a better world, the name for one path history can take, a dynamic, tumultuous, agonising process, with no end. Struggle forever."[14] If we recast utopianism along Robinson’s lines, what might be its lessons for navigating our climate-changed world? To answer this question, I propose we distinguish between three mechanisms that utopias deploy: estranging, galvanising, and cautioning. All utopias aim to exercise their critique of the status quo by doing one or several of these things. This can be illustrated through a quick glance at recent instances of theory-building and storytelling that grapple directly with our climate-changed world. Let us commence with estranging. When utopias make the extraordinary look ordinary, they seek to unsettle the audience’s common sense and therefore open up possibilities for transformation. One way of interpreting Bruno Latour’s recent appropriation of the Gaia figure is, accordingly, to decipher it as a utopian vision that hopes to disabuse its readers of anthropocentric views of the planet.[15] While James Lovelock initially came up with the idea to envisage Earth in terms of a self-regulating system, baptising the entirety of feedback loops of which the planet is composed with the mythological name “Gaia”, Latour attempts to vindicate a political ecology that repudiates the binary opposition of nature and culture, which obstructs a responsible engagement with environmental issues. From this, a deliberately strange image of Earth emerges, wherein agency is radically dispersed across multiple forms of being.[16] In N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, to refer to an interesting case of politically generative fantasy, our home planet is depicted as a vindictive agent that wages permanent war on its human occupants.[17] The upshot of this portrayal of the planetary habitat as a living, raging being, rather than a passive, calm background to humanity’s sovereign actions, is that the readers’ expectations of their natural surroundings are held in abeyance. Jemisin’s work captures Earth and its inhabitants through powerful allegories of universal connectedness—neatly termed “planetary weirding”[18]. What is more, the Broken Earth trilogy also sheds light on the shifting intersections of class, gender, racial, and environmental harms.[19] Hence, narratives such as this unfold plotlines that produce estrangement: they come up with imagined scenarios, which defamiliarise us from what we habitually take for granted.[20] Galvanising stories casts utopian visions in a slightly different light. These narratives describe alternatives whose purpose resides in revealing optimistic perspectives about the future. In contemporary environmentalist discourse, ecomodernists enlist this kind of emplotment strategy, most notably through their provocative belief that science and technology might eventually expedite a “decoupling” of human needs from natural resource systems.[21] Kim Stanley Robinson’s Science in the Capital trilogy inspects this alluring proposition with inimitable insight.[22] In his account of how the American scientific community might marshal its expertise to redirect the entire Washington apparatus onto a sustainable policy platform, Robinson attempts to establish that viable paths out of the current impasse do already exist—if only all the actors involved finally recognised the severity of the situation. The chief ambition behind this utopian frame is thus to affectively galvanise an audience that is at the moment either apathetic about its capacity to transform the status quo or paralyzed by the many hurdles that lie ahead. Finally, cautionary tales follow a plotline that is predicated on a bleaker judgment: unless we change our settled ways of being and living, the apocalypse will not be averted. Dystopian stories pursue this instruction by excavating hazardous trends that remain concealed within the current moment. Commentators such as Roy Scranton[23] or David Wallace-Wells[24] maintain that there is little we can do to slow down the planetary breakdown and the eventual demise of our own species. Margaret Atwood’s dystopian MaddAddam trilogy takes one step further when she prompts the reader to imagine how life after the cataclysmic collapse of human civilisation might look like.[25] The main task of this sort of narrative is to warn an audience about risks that are already present right now, but whose scale has not yet been fully appreciated in the wider public.[26] These three compressed cases show that the utopian imagination has much to add to the public debate around climate change; a debate that is about so much more than just plausible theories or appealing stories. Conjuring alternatives is as much about the modelling of other ways of being and living as it is about spurring resistant action. Social dreaming does not only involve abstract thought experiments; it also prompts a restructuring of human behaviour and as such proves to be deeply practical.[27] The climate emergency has, among many terrible outcomes, triggered a profound crisis of the imagination and action.[28] In this context, and despite legitimate worries about the deleterious aspects of social dreaming, we cannot afford to discard the estranging, galvanising, and cautioning impact that utopias generate. As one of the protagonists of the Science in the Capital trilogy declares: “We’re going to have to imagine our way out of this one.”[29] Acknowledgments With many thanks to Richard Elliott for the invitation to write this piece as well as for useful comments; and to Mihaela Mihai for productive feedback on an earlier draft. The research for this text has benefitted from a Research Fellowship by the Leverhulme Trust (RF-2020-445) and draws on work from my forthcoming book No Other Planet: Utopian Visions for a Climate-Changed World (Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022). [1] For a useful compendium of resources on the rise of (negative) emotions during the current climate crisis, see: https://www.bbc.com/future/columns/climate-emotions [2] The best example of this attitude can probably be found in Bill Gates’ recent endorsement of such solutionism. See: How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021). [3] Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). [4] Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope: Volume 1, trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight, Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 7, 9. [5] For a groundbreaking study, see: Lisa Garforth, Green Utopias: Environmental Hope before and after Nature (Cambridge: Polity, 2018). [6] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The Communist Manifesto,” in Selected Writings, by Karl Marx, ed. David McLellan, 2nd ed. (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 245–71. [7] On the anti-utopianism of these so-called “Cold War liberals”, see: Richard Shorten, Modernism and Totalitarianism: Rethinking the Intellectual Sources of Nazism and Stalinism, 1945 to the Present (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 109–49. [8] Lucy Sargisson, Fool’s Gold? Utopianism in the Twenty-First Century (Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). [9] Miguel Abensour, “William Morris: The Politics of Romance,” in Revolutionary Romanticism: A Drunken Boat Anthology, ed. Max Blechman (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1999), 126–61. [10] Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” Utopian Studies 5, no. 1 (1994): 1–37. [11] Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia, Student Edition (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2011); Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstruction of Society (Houndmills/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [12] On Le Guin and especially her masterpiece The Dispossessed, see: Tony Burns, Political Theory, Science Fiction, and Utopian Literature: Ursula K. Le Guin and the Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008); Laurence Davis and Peter Stillman, eds., The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2005). [13] Tom Moylan, Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination, ed. Raffaella Baccolini, Classics Edition (1986; repr., Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014). [14] Kim Stanley Robinson, Pacific Edge, Three Californias Triptych 3 (New York: Orb, 1995), para. 8.10. [15] Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, E-book (Cambridge/Medford: Polity, 2017). [16] See also: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010). [17] The Fifth Season, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 1 (New York: Orbit, 2015); The Obelisk Gate, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 2 (New York: Orbit, 2016); The Stone Sky, E-book, Broken Earth Trilogy 3 (New York: Orbit, 2017). [18] Moritz Ingwersen, “Geological Insurrections: Politics of Planetary Weirding from China Miéville to N. K. Jemisin,” in Spaces and Fictions of the Weird and the Fantastic: Ecologies, Geographies, Oddities, ed. Julius Greve and Florian Zappe, Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 73–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28116-8_6. [19] Alastair Iles, “Repairing the Broken Earth: N. K. Jemisin on Race and Environment in Transitions,” Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 7, no. 1 (July 11, 2019): 26, https://doi.org/10/ghf4k5; Fenne Bastiaansen, “The Entanglement of Climate Change, Capitalism and Oppression in The Broken Earth Trilogy by N. K. Jemisin” (MA Thesis, Utrecht, Utrecht University, 2020), https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/399139. [20] Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: Studies in the Poetics and History of Cognitive Estrangement in Fiction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978). [21] John Asafu-Adjaye, et al., “An Ecomodernist Manifesto,” 2015, http://www.ecomodernism.org/; See also: Manuel Arias-Maldonado, “Blooming Landscapes? The Paradox of Utopian Thinking in the Anthropocene,” Environmental Politics 29, no. 6 (2020): 1024–41, https://doi.org/10/ggk4vj; Jonathan Symons, Ecomodernism: Technology, Politics and the Climate Crisis (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019). [22] Forty Signs of Rain, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 1 (New York: Bantham, 2004); Fifty Degrees Below, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 2 (New York: Bantham, 2005); Sixty Days and Counting, E-book, Science in The Capital Trilogy 3 (New York: Bantham, 2007). [23] Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization, E-book (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015). [24] The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming, E-book (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019). [25] Oryx and Crake, E-book, vol. 1: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2003); The Year of the Flood, E-book, vol. 2: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2009); MaddAddam, E-book, vol. 3: MaddAddam Trilogy (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2013). [26] Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History: A Study of Modern Despotism, Its Antecedents, and Its Literary Diffractions, First edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). [27] In the 1970s, the Swiss sociologist Alfred Willener coined the term “imaginaction” to capture what is distinct about action facilitated through imagination and imagination stirred by action. See: Alfred Willener, The Action-Image of Society: On Cultural Politicization (London: Tavistock Publications, 1970). [28] Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, E-book (London: Penguin, 2016), para. 9.2. [29] Robinson, Sixty Days and Counting, para. 58.11. by Joshua Dight

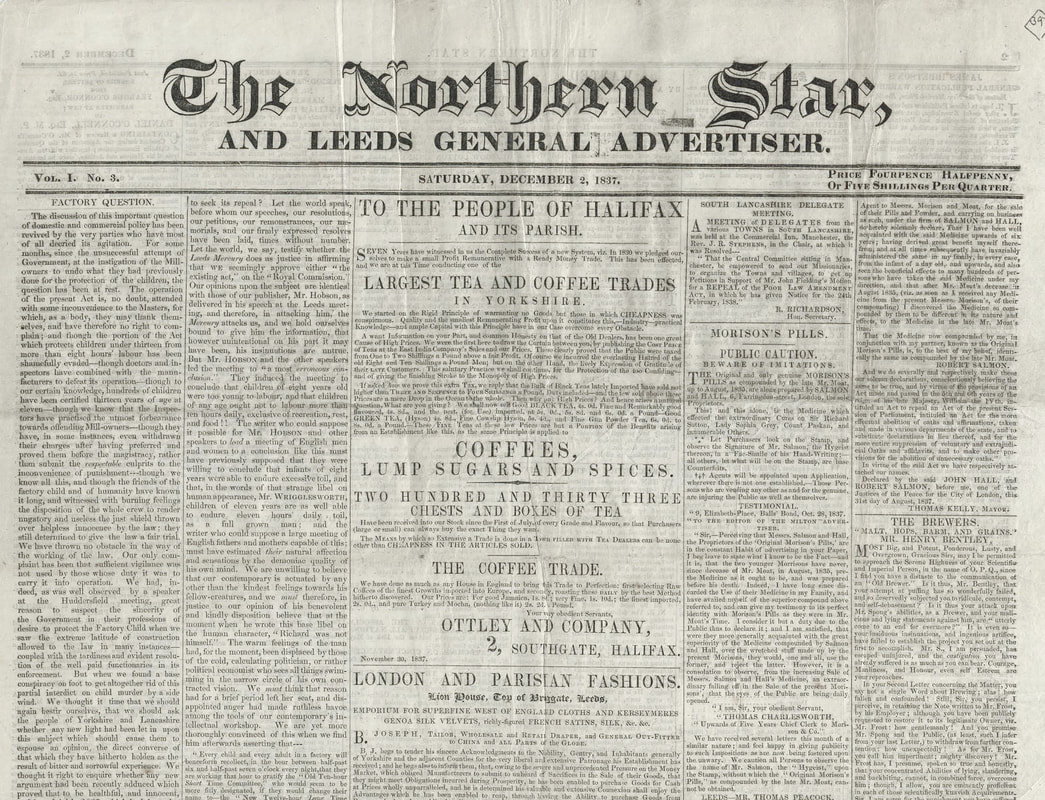

Today, you do not need to go far to locate debates on how to remember the past. From public squares in Glasgow to parks in Australia, questions over statues have been drawn into an open contest. However, this opposition over meaning, and the fight for one reading of history over another is not a new phenomenon. As the title of this piece of writing suggests—How to Read History?—it comes not from the latest newspaper headline, but rather, the past itself. Printed in the Chartist newspaper the Northern Liberator in 1837 at the outset of this mass working- and middle-class movement, the article spoke to the mood of radicals by rejecting established historical narratives that favoured elites. ‘George the third’ for instance, is portrayed as a ‘cold hearted tyrant’ and a ‘cruel despot’, not an uncommon refrain amongst radicals and their chosen lexicon in the unrepresentative political structure of Britain during this period and George III’s reign (1760-1820).[1] Yet, this reimagining does strike upon the issue of locating ‘truths’ within the past, and, by inference, falsehoods. As this article explores, Chartist responses to the existing composition of an anti-radical historical narratives gave them the opportunity to voice their ideology and make commemoration am instrument of their opposition.

From the late 1830s through to the early 1850s, Chartists nurtured this attachment to the past in the pursuit of the Six Point Charter (hence Chartism). These core demands guided the principles of Chartism, and included suffrage for all men over the age of 21, annual Parliaments, the secret ballot, eliminating property qualifications for becoming a Member of Parliament (MP), ensuring equal electoral districts, and supplying MPs with salaries.[2] Fulfilling the Six Point Charter promised the means to restructure the political system away from an ‘Imperial’ institution of ‘class legislation’ and move towards ‘the empire of freedom’.[3] Even at the earliest stages of Chartism, the past was instrumentalised and narrativised as an expression of politics. Chartists evoked a welter of radical heroes from a wide and sprawling pantheon. It brought together mythicised patriots like Wat Tyler, the leader of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, with recently deceased radicals like Henry Hunt, Britain’s preeminent orator of radicalism and a leading figure at the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.[4] Its application was flexible and accessible, with an intangible pantheon at surface level ready to be put to use within the rhetoric of those agitating for the Charter. The deployment of memory as an expression of protest can be found at different levels of Chartism. The work of the great Chartist historian Malcolm Chase identified fragments of a radical past within the language of the three great National Petitions Chartism produced and presented to Parliament. In 1839 this document invoked Britain’s constitutional past with reference to the Bill of Rights 1689, whereas the petitions of 1842 and 1848 moved towards using the idioms of the American and French Revolutions.[5] Viewed more generally, memory was a presence in Chartism that was flexible enough to contribute to arguments concerning a myriad of issues, such as whether force should be used in order to obtain the Charter if the petitions failed, along with discussions on what it meant to be a Chartist. This subsequently contributed to personalities like Thomas Paine, the republican author of Common Sense (1776) and Rights of Man (1791), and the radical journalist William Cobbett being redescribed as something akin to proto-Chartist in the rhetoric of meetings held across the country. The past was something practical, and the Chartists put it to use. This engagement with the past saw Chartists responded to ‘libels’ on radical memory by constructing their own marginalised histories that spoke to their ideology.[6] One clear example of this intervention was radical journalist Bronterre O'Brien’s ‘The Life and Character of Maximillian Robespierre’.[7] In this work, he sought to recover the lawyer and the French Revolution from Burkean denouncements of earlier generations. O'Brien’s ‘long promised’ dissenting narrative recast this context by emphasising its democratic qualities in the minds of readers and erasing images of the Terror. He considered the French Revolution as something requiring attention, and to encourage a kinship with this ‘democratic’ episode. The production and celebration of such histories opposed the output of Whiggish narratives that venerated ‘tradition made malleable by change’. [8] The output of the Edinburgh Review and works like Henry Cockburn’s Examinations of State Trials set out a narrative that was paternalistic and progressive in tone. Worse still for Chartists, moments identifiable as radical victories over a repressive state were claimed by Whigs and incorporated into tales of liberty and progress.[9] Vexation for the Whig government and their handling of the restructuring of Britain’s political system with the Reform Act in 1832 showed how lacking Whig histories were from a Chartist perspective. By reframing the historical narrative, Chartists were able to express their ideology by lionising the memory of radicals whilst puncturing Whig readings that supported the social hierarchy. This relationship with the past was not confined to the written word. Chartists were practitioners of remembrance and celebrated the memory of the ‘illustrious dead’ at banquets and dinners that anchored their political opposition. By the late 1830s regular meetings across the country saw radical icons honoured. Reading over newspaper reports of these gatherings reveals the orderly manner in which these affairs were conducted – the announcement of a chairman, polite speeches, and finally a selection of toasts, often conducted in ‘solemn silence’. As is the case with memory formation, the roots of these rituals of remembrance are complex. They were, in part, taken from elite dining culture or were developed by radicals in the earlier part of the nineteenth century.[10] Chartists assumed these civilised niceties, but crucially, as with O’Brien’s penwork, recalibrated them to remove the sting of anti-radicalism. In halls, taverns, and homes, Chartists rehabilitated the memories of their patriots through singing about the career of Paine, toasting Cobbett, or cheering Hunt’s heroic stand at the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. This organised culture of commemoration served Chartism by encouraging and structuring social engagement with its ideology. One of the key attributes of memory is its function as something inherently sociable, inviting the community to participate in ceremonies and share in the past.[11] Evidence of this communal festivity is found in the many anniversaries of a radical’s birth or death that were adhered to.[12] These frequent fixtures were often promoted in the Chartist press beforehand, showing the dedication to memory and its importance in uniting radicals. Notices included titles that read ‘THOMAS PAINE’S BIRTHDAY’, or tickets available to those wishing to spend an evening dining to the memory of William Cobbett.[13] These anniversaries were a stimulant to popular protest, a particularly useful quality for a movement like Chartism that rested on mobilising the masses. This collection of radical anniversaries and the reports they produced speaks to the structure commemoration provided. The value of anniversaries to a protest movement like Chartism should not be underestimated. Memory is inherently social and, as observed by the Chartists, encouraged exchanges between persons within the community and other constituencies. Details of this coverage reveal that anniversaries events, such as the birthday of Henry Hunt, allowed for opportunities to celebrate the memories of other heroes in the radical pantheon. This was particularly true for places like Ashton-under-Lyne which had a strong radical tradition. A newspaper report of one such commemorative dinner to Hunt in November 1838 reveals the breadth of patriots honoured, from Irish romantic hero Robert Emmett, to the Scottish Martyrs.[14] These proliferations of commemoration allowed Chartism to act as a juncture in which the wide sprawling past intersected. For instance, during the same dinner, Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor personified this interaction between past and present. As a symbol of Chartism, he was at one point described as the ‘father of reform’, a title initially bestowed to Paine, and later in the evening, aligned with Hunt, who ‘could not be dead while Feargus O'Connor was alive’.[15] Here, the strongest symbol of Chartism, O’Connor himself, was imprinted onto the projections of those being commemorated The connection established here speaks to the reciprocal relationship in which Chartists popularised the memory of radicals whilst inscribing the hallmarks of Chartism. Not only then did the collection of radical anniversaries offer structure, their calendrical qualities secured moments in the year that guaranteed the practice and pronouncement of Chartism’s opposition to the state with almost limitless personalities to deploy as an expression of their protest. These festivities were frequently reported on and circulated in the Chartist press. Indeed, the popularity of these affairs was such that some felt it necessary to hold newspapers to account for not reporting upon them.[16] Studying these newspaper reports shows a spike in commemoration through the months of January, March and November in honour of Thomas Paine, William Cobbett and Henry Hunt. At times, multiple reports of these banquets are scattered throughout the issues of newspapers like the Northern Star. This Chartist press was crucial to helping to sustain the movement itself, with newspapers acting as a channel for Chartism’s ideology and showcasing to readers the national activity of the movement. Yet, it should not be forgotten that these newspapers were also vital in capturing and bringing together Chartism’s culture of commemoration. These transcriptions allowed readers to reexperience the remembrance of their past patriots, and so share in any ideological impressions placed onto memory. By analysing newspaper reports we can gain further insights into how a dedicated commemoration culture allowed the past to be recalled in order to serve the politics of Chartism. At a ‘Great Demonstration in Commemoration of the Peterloo Massacre’, held at Manchester and reported in the Northern Star on 18th August 1838, attendees discussing the adoption of what would become the 1839 National Petition did so on a sacred site of memory.[17] Nineteen years before, in August 1819, protesters at St. Peters Field gathered to listen to Henry Hunt on the right to political representation. The response from local magistrates was heavy handed and resulted in the violent use of force on the crowd. The memory of the Peterloo Massacre was sacred to Chartists, and this sense of the past contributed an historical significance to the meeting. In addition to the symbolism memory leant to the staging of this affair, visual displays in the form of banners, flags, portraits, and old ballads that all contributed to creating a sense of the past at this important juncture in Chartism. Within these surroundings, Chartists expressed their animosity towards Britain’s ruling elites; Whigs and their cheap ‘£10 Reform Bill’, along with ‘Sir Robert Bray Surface Peel’ and his Tory supporters.[18] The clearest sign of memory combining with this political expression came later on, when personalities of reform—Major John Cartwright, Cobbett, and Hunt—were declared as the tutors of radicalism. Through the didacticism of their memories, Chartism was made a part of this earlier radical narrative. At the same time, by making these figures of reform relevant, they were inducted into Chartism and used as devices that allowed Chartists to express their commitment to the cause. Celebrations of the past were not always grandiose events but could be small local affairs. Sacred sites of memory or the possession of radical relics were not a prerequisite for social gatherings to take place, nor for the past to be invited into proceedings. This accessibility to a common view of the past speaks to the pervasive nature of memory, and personalities from the pantheon of the ‘illustrious dead’ could be recalled when necessary at local dinners or banquets. The flexible qualities of memory allowed it to be remembered and applied however needed. Conjuring the past in this way was particularly useful to a political movement like Chartism, which was formed through a patchwork of regional affairs mixing with common political grievances felt across the country. Drawing on a common past helped to inspire a sense of unity. Whilst some attendees may have taken umbrage at how an illustrious patriot was represented, the malleability of memory allowed Chartists to immediately render the radical relevant to the current debate. Paine could be invoked for his ardent republicanism, as a working-class hero, or enlightened philosopher. Memories of radicalism not only helped to inspire a spirit of protest, but circulated a political language, contributing rhetorical devices at meetings that were subsequently captured and reported in the Chartist press, thus consolidating the ideological foundations of Chartism. As discussions on the collective nature of anniversaries has shown, celebrations of a shared past helped to remedy some of the fractures within the Chartist movement, for instance, splits among the leadership, or disagreements on the use of physical force (‘ulterior measures’) to obtain the Charter.[19] The mere evocation of an intangible past did not prevent these divisions from occurring. However, uniting to celebrate radicalism’s key moments and an ‘illustrious dead’ helped to restore a degree of cohesion. Recognition of this ability to overcome fault lines within the movement only heightens the remarkable nature of Chartism’s commemoration culture. Despite the different locations, diverging interpretations of the past or political viewpoints, memory provided intersections within a wide national movement of regional affairs in the nineteenth century. Commemorations of the past continued to be a part of Chartism until its decline following the last of the great National Petitions in 1848. In being able to reach for a familiar past, Chartists were able to enthuse a spirit of protest and celebrate intervals in the calendar year with anniversaries that strengthened their ideological commitments. This pantheon of radical heroes continues to be mobilised today, and, arguably, has only grown in number. Perhaps the most recent personality to be recovered and admitted is William Cuffay, the black Chartist and long-term political activist. These figures are a reminder of the potency of memory as an expression of protest and the malleability of the past when ideology is put into practice. [1] Northern Liberator, 9 December 1837. [2] J. R. Green, A Short History of the English People (1874), 859. [3] Northern Star, 24 October 1840. [4] Matthew Roberts, Chartism, Commemoration and the Cult of the Radical Hero (Routledge, 2019), 3. [5] Malcolm Chase, ‘What Did Chartism Petition For? Mass Petitions in the British Movement for Democracy’, Social Science History, 43.3 (2019), 531–51. [6] Katharine Hodgkin and Susannah Radstone, Contested Pasts: The Politics of Memory (Routledge, 2003). [7] Northern Star, 17 March 1838. [8] David Lowenthal, The Past Is a Foreign Country - Revisited (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 181. [9] Gordon Pentland, Michael T. Davis, and Emma Vincent Macleod, Political Trials in an Age of Revolutions: Britain and the North Atlantic, 1793-1848, Palgrave Histories of Policing, Punishment and Justice (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 215. [10] Roberts, Chartism, Commemoration, xii; James Epstein, Radical Expression: Political Language, Ritual, and Symbol in England, 1790-1850 (Oxford University Press, 1994), 192. [11] Geoffrey Cubitt, History and Memory, History and Memory (Manchester University Press, 2013), 219-20. [12] Steve Poole, ‘The Politics of “Protest Heritage”, 1790-1850’, in C. J. Griffin and B. McDonagh (eds.), Remembering Protest in Britain since 1500 Memory, Materiality, and the Landscape (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 194. [13] Northern Star, 8 January 1842. [14] Northern Star, 17 November 1838. [15] Ibid. [16] Northern Star, 6 February 1841. [17] Northern Star, 18 August 1838. [18] Ibid. [19] Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 67. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed