by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

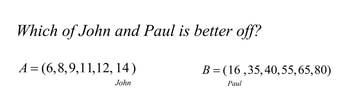

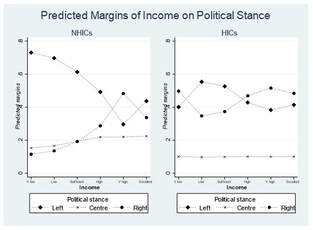

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

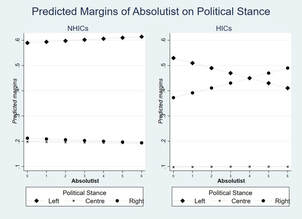

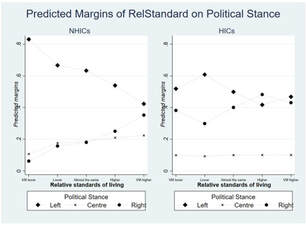

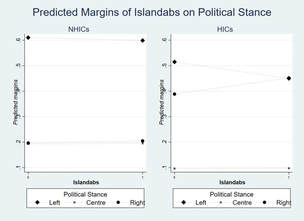

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. by Jack Foster and Chamsy el-Ojeili

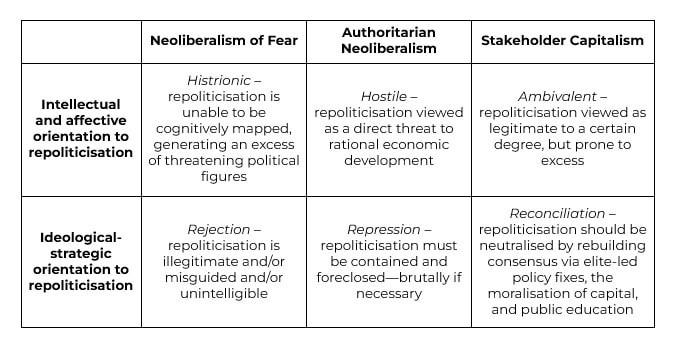

In September 2021, penning his last regular column for the Financial Times after 25 years of writing on global politics, Philip Stephens reflected on a bygone age. In the mid-1990s, an ‘age of optimism’, Stephens writes, ‘the world belonged to liberalism’. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the integration of China into the world economy, the realisation of the single market in Europe, the hegemony of the Third Way in the UK, and the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance presaged a century of ‘advancing democracy and a liberal economic order’. But today, following the financial crash of 2008 and its ongoing fallout, and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘policymakers grapple with a world shaped by an expected collision between the US and China, by a contest between democracy and authoritarianism and by the clash between globalisation and nationalism’.[1] Only five months later, the editors of the FT judged that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had definitively closed the ‘chapter of history opened by the fall of the Berlin Wall’; the sight of armoured columns advancing across the European mainland signals that a ‘new, darker, chapter has begun’.[2] At this juncture, with the all-consuming immediacy of the war in Ukraine, and the widespread appeal of framing the conflict in civilisational terms—Western liberal democracy facing down an archaic, authoritarian threat from the East—it is worth reflecting on some of the currents that flow beneath and give shape to the discourse of Western liberal elites today. In a previous essay, we argued that the leading public intellectuals and governance institutions of Western capitalism have struggled to effectively interpret and respond to the political and economic turmoil first unleashed by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008.[3] We traced out a crisis of intellectual and moral leadership among Western elites in the splintering of (neo)liberal discourse over the past decade-and-a-half—the splintering of what was, prior to the GFC, a relatively consensual ‘moment’ in elite discourse, in which cosmopolitan neoliberalism had reigned supreme. As has been widely argued, the financial crisis brought this period of confidence and self-congratulation to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Both the enduring economic malaise that followed the crash, and the crisis of political legitimacy that has unfolded in its wake, have shaken the intellectual and ideological certitude of Western liberals. All political ideologies experience ‘kaleidoscopic refraction, splintering, and recombination’, as they are adapted to historical circumstances and combined with elements of other worldviews to produce novel formations.[4] However, we argued that the post-GFC period has seen a particularly intense and marked splintering of (neo)liberal discourse into three distinctive but overlapping and intertwining strands or ‘moments’. First, a neoliberalism of fear,[5] which is animated by the invocation of various dystopian threats such as populism, protectionism, and totalitarianism, and which associates the contemporary period with the extremism and instability of the 1930s. Second, a punitive neoliberalism, which seeks to conserve and reinforce existing power relations and institutions of governance.[6] And third, a pragmatic and reconciliatory neo-Keynesianism, oriented above all to saving capitalism from itself. In this essay, we want to expand upon one aspect of this analysis. Specifically, we suggest here that one way in which we can distinguish between these three strands or ‘moments’ is as distinct responses to the repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management in the years following the GFC. Respectively, these responses can be summarised as rejection, repression, and reconciliation (see Table 1, below). Depoliticisation and repoliticisation In our previous essay, we argued that the 1990s and early 2000s were marked by the predominance of cosmopolitan neoliberalism as a successful project of intellectual and moral leadership, the moment of the ‘end of history’ and ‘happy globalisation’. In this period, we saw the radical diminution of economic and social alternatives to capitalism, the colonisation of ever more spheres of social life by the market, the transformation of common sense around the proper relationship between states and markets, the public and the private, equality and freedom, the community and the individual, and the institutionalisation of post-political management, or what William Davies has called ‘the disenchantment of politics by economics’.[7] Of this last, neoliberalism, as both a political ideology and a set of institutions, has always been oriented to the active depoliticisation and indeed dedemocratisation of ‘the economy’ and its management—what Quinn Slobodian calls the ‘encasement’ of the market from the threat of democracy.[8] In practice, this has been pursued in two primary ways. First, it has been accomplished via the legal and institutional insulation of ‘the economy’ from democratic contestation. Here, the delegation of critical public policy decisions to unelected, expert agencies such as central banks and the formulation of rules-based economic policy frameworks designed to narrow political discretion are emblematic. Second, this has been buttressed by ideological appeals to the constraints placed upon domestic economic sovereignty by globalisation and the necessity of technocratic expertise in government—strategies that lay at the heart of the Clinton administration in the US (‘It’s the economy, stupid!’) and the Third Way of Tony Blair in the UK. Economic management was to be left to Ivy League economists, central bankers, and the financial wizards of Wall Street and the City. The so-called ‘Great Moderation’—the period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that was characterised by low macroeconomic volatility and sustained, albeit unspectacular, growth in most advanced economies—lent credence to these ideas. The hubris of elites in this period should not be underestimated. As Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the influential Bank for International Settlements, put it to an audience of European financiers in 2019, ‘During the Great Moderation, economists believed they had finally unlocked the secrets of the economy. We had learnt all that was important to learn about macroeconomics’.[9] And in his ponderous account of how global capitalism might be saved from the triple-threat of financial instability, Covid-19, and climate change, former governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney recalls ‘how different things were’ prior to the credit crash—a period of ‘seemingly effortless prosperity’ in which ‘Borders were being erased’.[10] The GFC catalysed both an epistemological crisis in mainstream economics, and, after some delay, the rise of anti-establishment political forces on both the left and the right. The widespread failure to reflate economic development in the wake of the crisis and the punishing effects of austerity in the UK and the Eurozone, and at the state level in the US, only exacerbated the problem. Over the past decade-and-a-half, questions of economic development, of who gets what, and of who should be in charge, have come back on the table. How have Western elites responded? Rejection One dominant response to this repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management has been to invoke a host of dystopian figures—populism, nationalism, political extremism, protectionism, socialism, and totalitarianism—all of which are perceived as threats to the stability of the open-market order, to economic development, and to a thinly defined ‘liberal democracy’. This is the neoliberalism of fear Four years prior to the election of Donald Trump, the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks’ assessment was already grimly warning that the ‘seeds of dystopia’ were borne on the prevailing winds of ‘high levels of unemployment’, ‘heavily indebted governments’, and ‘a growing sense that wealth and power are becoming more entrenched in the hands of political and financial elites’ following the GFC.[11] In 2013, Eurozone technocrats were raising cautious notes around the ‘renationalisation of European politics’.[12] By 2015, Martin Wolf, long-time economics columnist for the FT, was informing his readers that ‘elites have failed and, as a result, elite-run politics are in trouble’.[13] This climate of fear reached fever-pitch in 2016, with the shocks delivered by the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, and again in January 2021, with mounting fears that President Biden’s inauguration would be blocked by a truculent Republican party. The utopian world of the long 1990s, in which globalisation was ‘tearing down barriers and building up networks between nations and individuals, between economies and cultures’, in the words of Bill Clinton, has thus disappeared precisely as ‘the economy’ and its management began to be repoliticised.[14] Two aspects of this often-histrionic neoliberalism of fear stand out. First, we see a striking inability to cognitively map the repoliticised terrain. Rather than serious attempts to map out why and in what ways repoliticisation is occurring, this strand or ‘moment’ is characterised by a reliance on a set of questionable historical analogies, above all the 1930s and the disasters of totalitarianism. Second, extraordinary weight is given over to these threats and fears, and there is a corresponding absence of serious attempts to construct a new ideological consensus. Instead, repoliticisation is countered in a language that is defensive, hectoring, and dismissive. For Wolf, populist forces have organised to ‘muster the inchoate anger of the disenchanted and the enraged who feel, understandably, that the system is rigged against ordinary people’.[15] In like fashion, former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, reflecting on his role in resolving the GFC, writes that in crises, ‘fear and anger and ignorance’ clouds the judgement of both the public and their representatives and impedes sensible policymaking; it is essential, in times of crisis, that decisions are left to coldly rational technicians.[16] Musing on the integration backlash in the EU, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, noted that while ‘protectionism is society’s natural response’ to unchecked market forces, it is crucial to ‘resist protectionist urges’, and this is the job of enlightened technocrats and politicians, who must hold back the populist forces threatening to roll back market integration.[17] In other words, while recognising that a rampaging globalisation has driven social and political unrest, within this neoliberalism of fear the masses are viewed as too capricious and ignorant to be trusted; the post-GFC malaise, while frightening and disorienting, will certainly not be solved by more democracy. Repression Closely related to, and overlapping with, this neoliberalism of fear is the second core strand or ‘moment’, that of a punitive and coercive neoliberalism. If the neoliberalism of fear can be understood as a dismissive overreaction to repoliticisation, this second strand represents a more direct and focused attempt to manage this new, more unstable, and more contested political economy. Fears of deglobalisation, of protectionism, of fiscal recklessness are also prominent in this line of argument; however, equally prominent are the necessary solutions: strengthening the rules-based global order, ongoing flexibilisation and integration of labour and product markets—particularly in the EU—and a harsh but altogether necessary process of fiscal consolidation. The problem of public debt has, of course, been one of the major battlegrounds here. Preaching the necessity of fiscal consolidation at the elite Jackson Hole conference in 2010, for example, Jean-Claude Trichet raised the cautionary tale of Japan, a country that ‘chose to live with debt’ in the 1980s and suffered a ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s as a result.[18] These concerns were widely echoed in the financial press and by international policy organisations; here, the threat of market discipline was also consistently evoked as justification for fiscal retrenchment and punishing austerity. As former IMF economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff infamously warned, prudent governments pay down public debt, because ‘market discipline can come without warning’.[19] Much has been made of the punitive, moralising, and post-hegemonic dimensions of this discourse.[20] However, it is worth bearing in mind that there are also genuine attempts to match the policy prescriptions associated with this more authoritarian and coercive neoliberalism—fiscal austerity, enhanced fiscal discipline and surveillance, structural adjustment, rules-based economic governance—with a positive vision of the political economy that these policies will deliver: economic growth, global economic stability, a route out of the post-GFC doldrums. Viewed in this way, the key ideological thrust here seems to be less that of punishment for punishment’s sake than it is of the deliberate repression and foreclosure of repoliticisation. Pace the classical neoliberal thinkers, the driving logic is that economic development and economic management are far too important to be left to democracy, which is altogether too fickle and too subject to capture by interest groups to be trusted. The upshot? Austerity, flexibilisation, the strengthening of the elusive rules-based global order: all this must be pushed through regardless of dissent. As with any ideological formation, shutting down alternative arguments is also important. As one speaker at the Economist’s 2013 ‘Bellwether Europe Summit’ put it, ‘the political challenge’ to structural adjustment ‘comes not from the process of adjustment itself. People can accept a period of hardship if necessary. It comes from the belief that there are better alternatives available that are being denied’.[21] In these ways, this second strand or ‘moment’ is directly hostile to the return of the political: less a hurried and defensive pulling-up of the drawbridge, as in the neoliberalism of fear, than a concerted counterattack. Reconciliation While this punitive and coercive neoliberalism seeks to repress repoliticisation by further insulating ‘the economy’ and its management from democratic interference, the third main strand of post-GFC (neo)liberal discourse responds to repoliticisation in a more measured way. In our previous writing on this issue, we referred to this strand or ‘moment’ as a pragmatic neo-Keynesianism, which promotes technocratic policy fixes aimed at lightly redistributing wealth and rebuilding the social contract. Over the past couple of years, we suggest, these more reconciliatory energies have coagulated into a relatively coherent ideological project, that of stakeholder capitalism.[22] Simultaneously, aided by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism of the 2010s has been discredited and has largely vanished from the pages of the financial press, the policy recommendations of the major international organisations, and the books and columns of Western public intellectuals. Thus, we use the term stakeholder capitalism to refer to the recent ideological shift in the Western policy establishment, among public intellectuals, and in business and high finance, that centres around the push for more ‘socially responsible’ corporations, for ‘green finance’, and for the re-moralisation of capitalism. By 2019, this shift was gathering momentum. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz implored readers of the New York Times to help build a ‘progressive capitalism’, ‘based on a new social contract between voters and elected officials, between workers and corporations, between rich and poor, and between those with jobs and those who are un- or underemployed’.[23] The FT launched its ‘New Agenda’, informing its readers that ‘Business must make a profit but should serve a purpose too’.[24] The American Business Roundtable, the crème de la crème of Fortune-500 CEOs, issued a new ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’, in which it revised its long-standing emphasis on promoting shareholder-value maximisation. Rather than narrowly focusing on returning profit to their shareholders, it now claims that corporations should ‘focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone—investors, employees, communities, suppliers, and customers’.[25] Similarly, the WEF launched its 50th-anniversary ‘Davos Manifesto’ on the purpose of a company, promoting the development of ‘shared value creation’, the incorporation of environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into company reporting and investor decision-making, and responsible ‘corporate global citizenship […] to improve the state of the world’.[26] And no lesser figure than Jaime Dimon, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, noted in his 2019 letter to shareholders that ‘building shareholder value can only be done in conjunction with taking care of employees, customers and communities. This is completely different from the commentary often expressed about the sweeping ills of naked capitalism and institutions only caring about shareholder value’.[27] Now, in early 2022, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, has announced that it will be launching a ‘Center for Stakeholder Capitalism’ in the near future.[28] The term ‘stakeholder management’ was originally coined by the business-management theorist Edward Freeman in the 1980s,[29] but the roots of this discourse go back to the dénouement of the first Gilded Age, where some business leaders began to promote the idea of the socially responsible corporation as a means of outflanking working-class discontent during the Great Depression.[30] The concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ then became popular in the 1990s, associated above all with the Third Way of New Labour.[31] Today, the discourse of stakeholder capitalism has been resurrected and updated, we suggest, in direct response to the repoliticisation of the economy and its management and the failure of authoritarian neoliberalism to provide a way out of the post-2008 quagmire. At the root of this rebooted version of stakeholder capitalism is an argument for the re-moralisation of capitalism in the interests of social cohesion and long-term sustainability. To be sure, there remains a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, consumer choice, and so on. But there is also a recognition of—or at least the payment of lip service to—the fact that a rampaging globalisation and widespread commodification has undermined social stability and cohesion. Thus, in contrast to the second strand or ‘moment’ of post-GFC (neo)liberalism, stakeholder capitalism seeks to deal with the repoliticisation of the economy and its management by establishing a more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. To establish a more inclusive capitalism means making some relatively significant shifts in economic policy. ‘[T]argeted policies that achieve fairer outcomes’ are the order of the day.[32] A more fiscally active state and investment in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D are all called for. So too is an expanded social-welfare safety net, primarily in the form of active labour-market policies. And above all, stakeholder capitalism is about tackling the green-energy transition, which presents, for boosters of a private-finance-led transition, ‘the greatest commercial opportunity of our time’.[33] This means ‘smart’ state intervention to steer and ‘derisk’ private investment.[34] Cultural reform, economic education, and democratic renewal are also viewed as important enabling features of this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. Here, policymakers must lead from the front, finding ways to better communicate with, and to educate, citizens and to foster consensus. In these respects, if the ‘moment’ of punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism was characterised by the repression of repoliticisation, then stakeholder capitalism seeks reconciliation. But while the legitimacy of democratic dissatisfaction is broadly recognised, and while there is a place for ‘more democracy’ in the discourse of stakeholder capitalism, this is democracy conceptualised not as the meaningful contestation of the distribution of power and resources, but as a relentless machine for building consensus. Opposing value systems and fundamental conflicts over the distribution of resources do not exist, only ‘stakeholder engagement’ oriented to revealing the ‘public interest’ or the preferences of ‘society’ at large. Exponents of stakeholder capitalism call for more education on how the economy works and emphasise the need to ‘listen’ more attentively to the citizenry. But the intention behind such endeavours is to develop or fortify consensus around already-existing institutions, or at best to tweak them at the margins. In these respects, there is an ambivalence running through this third—and perhaps now dominant—strand or ‘moment’: the mistrust of democracy, made explicit in the neoliberalism of fear and its authoritarian counterpart, is never completely out of the frame. Table 1: Rejection, repression, and reconciliation Horizons Despite its obvious limitations from the normative point of view of radical or even social democracy, the (re)emergent ideological formation of stakeholder capitalism does, we suggest, represent a relatively coherent attempt at rebuilding ideological consensus in Western societies. After years of intellectual and moral disorganisation, the rise to dominance of stakeholder capitalism among the policy establishment, high finance, some liberal intellectuals, and the financial press perhaps signals the reestablishment of intellectual and ideological discipline among elites. But it seems unlikely that this line of approach will bear fruit in the long run; the dysfunctions of the (neo)liberal world order—spiralling inequality and oligarchy, post-democratic withdrawal and outrage, resurgent nationalism, and anaemic, debt-dependent economic growth—run deep. More immediately, the war in Ukraine, and the unprecedented financial and economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers, threatens to once again reorder the ideological terrain and to intensify the shift away from globalisation. Perhaps the dominant response among (neo)liberal commentators thus far has been to frame the conflict as the first battle in a coming war for the preservation of liberal democracy: we are seeing the return of a more ‘muscular’ liberalism, reminiscent of the early years of the War on Terror.[35] Indeed, throughout modern history, war has served to restore liberalism’s ideological vigour; the conflict in Ukraine may yet prove to be a shot in the arm. [1] P. Stephens, ‘The west is the author of its own weakness’, Financial Times, 30 September 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9779fde6-edc6-4d4c-b532-fc0b9cad4ed9 [2] The Editorial Board, ‘Putin opens a dark new chapter in Europe’, Financial Times, 25 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a69cda07-2f63-4afe-aed1-cbcc51914105 [3] J. Foster and C. el-Ojeili, ‘Centrist Utopianism in Retreat: Ideological Fragmentation after the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 2021. [4][4] Q. Slobodian and D. Plehwe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian, and P. Mirowski (Eds), Nine Lives of Neoliberalism (London: Verso, 2020), p. 3. [5] N. Schiller, ‘A liberalism of fear’, Cultural Anthropology, 27 October 2016, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-liberalism-of-fear [6] W. Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’, New Left Review, 101 (2016), pp. 121-134. [7] W. Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty, and the Logic of Competition, revised edition (London: Sage, 2017). [8] Q. Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018). The reduction of essentially political problems to their economic dimension is a long-standing feature of liberalism as such and is therefore not an original aspect of neoliberalism; it is, however, particularly pronounced in the latter. [9] C. Borio, ‘Central banking in challenging times’, speech at the SUERF Annual Lecture, Milan, 2019. [10] M. Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 151. [11] World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2012 (Geneva: WEF, 2012), pp. 10, 19. [12] B. Cœuré, ‘The political dimension of European economic integration’, speech at the Ligue des droits de l’Homme, Paris, 2013. [13] M. Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What We Have Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 382. [14] William Clinton, ‘President Clinton’s Remarks to the World Economic Forum (2000)’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOq1tIOvSWg [15] Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks, p. 383. [16] T. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises (London: Random House, 2014), p. 209. [17] M. Draghi, ‘Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2017. [18] J-C. Trichet, ‘Central banking in uncertain times – conviction and responsibility’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2010. [19] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times, 28 January 2010. [20] See, for example, Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’. [21] J. Asmussen, ‘Saving the euro’, speech at the Economist's Bellwether Europe Summit, London, 2013. [22] J. Foster, ‘Mission-oriented capitalism’, Counterfutures 11 (2021), pp. 154-166. [23] J. Stiglitz, ‘Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron’, New York Times, 19 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [24] Financial Times, ‘FT sets the agenda with a new brand platform,’ Financial Times, 16 September 2019, https://aboutus.ft.com/press_release/ft-sets-the-agenda-with-new-brand-platform [25] Business Roundtable, ‘Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”’, 19 August 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [26] World Economic Forum, ‘Davos Manifesto 2020: The universal purpose of a company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’, 2 December 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/davos-manifesto-2020-the-universal-purpose-of-a-company-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/ [27] J. Dimon, ‘Annual Report 2018: Chairman and CEO letter to shareholders’, 4 April 2019, https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm?a=1 [28] L. Fink, ‘Larry Fink’s 2022 letter to CEOs: The power of capitalism’, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter [29] See E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984). [30] J. P. Leary, Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018), pp. 162-163. [31] For an early statement, see W. Hutton, The State We’re In (London: Random House, 1995). Freeman also wrote on the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ in the 1990s. It is notable that the drive to develop this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism is made in the absence of, and often disdain for, the key conditions that enabled Western social democracy to (briefly) thrive—namely, a more autarkic global political economy, mass political-party membership, high trade-union density, the ideological threat posed by Soviet communism, a more coherent and engaged public sphere, and stronger civil-society institutions. Further, exponents of stakeholder capitalism retain a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, and so on. For these reasons, we suggest that its closest ideological cousin is the Third Way. [32] B. Cœuré, ‘The consequences of protectionism’, speech at the 29th edition of the workshop ‘The Outlook for the Economy and Finance’, Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 2018. [33] Carney, Value(s), p. 339. [34] D. Gabor, ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52(3) (2021), pp. 429-459. [35] M. Wolf, ‘Putin has reignitied the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy’, Financial Times, 2 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b by Ben Williams

A burgeoning area of political research has focused on how the ideas and practical politics arising from the theories of the ‘New Right’ have had a major impact and legacy not only on a globalised political level, but also in relation to the domestic politics of specific nations. From a British perspective, the New Right’s impact dates from the mid-1970s when Margaret Thatcher became Leader of the Conservative Party (1975), before ascending to the office of Prime Minister in 1979. The New Right essentially rejected the post-war ‘years of consensus’ and advocated a smaller state, lower taxes and greater individual freedoms. On an international dimension, such political developments dovetailed with the emergence of Ronald Reagan as US President, who was elected in late 1980 and formally took office in early 1981. Within this timeframe, there was also associated pro- market, capitalist reforms in countries as diverse as Chile and China. While the ideas of New Right intellectual icons Friedrich von Hayek[1] and Milton Friedman[2] date back to earlier decades of the 20th century and their rejection of central planning and totalitarian rule, until this point in time they had never seen such forceful advocates of their theories in such powerful frontline political roles.

Thatcher and Reagan’s explicit understanding of New Right theory was variable, but they nevertheless successively emerged as two political titans aligned by their committed free-market beliefs and ideology, forming a dominant partnership in world politics throughout the 1980s. Consequently, the Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ that had traditionally incorporated shared cultural values and military and security co-operation, reached new heights amidst a decade very much dominated by New Right ideology. However, as we now look back over forty years on, debate has arisen as to what extent the ideas and values of the New Right are still relevant in the context of more contemporary political events, namely in relation to how the free market can appropriately react to major global crises. This has been notably applied to how various governments have reacted to both the 2007–8 global economic crash and the ongoing global Covid-19 pandemic, where significant levels of state intervention have challenged conventional New Right orthodoxies that ‘the free market knows best’. The New Right’s effect on British politics (1979-97) In my doctoral research into the evolution of contemporary Conservative Party social policy, the legacy and impact of the New Right on British politics formed a pivotal strand of the thesis, specifically how the UK Conservative Party sought to evolve both its image and policy agenda from the New Right’s free market economic emphasis into a more socially oriented direction. [3] Yet my research focus began at the tail end of the New Right’s period of hegemony, in the aftermath of the Conservative Party’s most devastating and humiliating electoral defeat for almost 100 years at the 1997 general election.[4] From this perspective of hindsight that looked back on eighteen years of continuous Conservative rule, the New Right’s influence had ultimately been a source of both rejuvenation and decline in relation to Conservative Party fortunes at different points of the electoral and historical cycle. In a positive sense, in the 1970s it appeared to revitalise the Conservative Party’s prospects while in opposition under the new leadership of Thatcher, and instilled a flurry of innovative, radical and eye-catching policies into its successful 1979 manifesto, which in subsequent years would be described as reflecting ‘popular capitalism’. Such policies would form the basis of the party’s accession to national office and consequent period of hegemonic rule throughout the 1980s in particular. The nature of such party-political hegemony as a conceptual term has been both analysed and explained in terms of its rise and fall by Andrew Gamble among others, who identified various core values that the Conservatives had traditionally stood for, namely ‘the defence of the Union, the defence of the Empire, the defence of the Constitution, and the defence of property’[5]. However, in a negative sense, by the mid to late 1990s, as Gamble identifies, the party appeared to have lost its way and had entered something of a post-Thatcher identity crisis, with the ideological dynamic instilled by the New Right’s legacy fatally undermining its previously stable equilibrium and eroding the traditional ‘pillars’ of hegemony’ as identified above. While Thatcher’s successor John Major was inclined to a more social as opposed to economic policy emphasis and between 1990-97 sought to distance himself from some of her harsher ideological policy positions, it was perhaps the case that the damage to the party’s electoral prospects had already been done. Not only had the Conservatives defied electoral gravity and won a fourth successive term in office in 1992, but the party’s broader ethos appeared to have become distorted by New Right ideology, and it became increasingly detached from its traditional instincts for pragmatic moderation located at the political centre, and notably its capacity to read the mood with regards the British public’s instinctive tendencies towards social conservatism, as has been argued by Oakeshott in particular. [6] Critics also commented that the New Right’s often harsh economic emphasis was out of touch with a more compassionate public opinion that was emerging in wider public polling by the mid-1990s, and which expressed increasing concerns for the condition of core public services. This was specifically evident in documented evidence that between ‘1995-2007 opinion polls identified health care as one of the top issues for voters.[7] The New Right’s focus on retrenchment and the free market was now blamed for creating such negative conditions by some, both within and outside the Conservative Party. Coupled with a steady process of Labour Party moderation over the late 1980s and 1990s, such trends culminated in major and repeated electoral losses inflicted on the Conservative Party between 1997 and 2005 (with an unprecedented three general election defeats in succession and thirteen years out of government). The shifting spectrum and New Labour When once asked what her greatest political achievement was, Margaret Thatcher did not highlight her three electoral victories but mischievously responded by pointing to “Tony Blair and New Labour”. It is certainly the case that Blair’s premiership from 1997 onwards was very different from previous Labour governments of the 1960s and 1970s, and arguably bore the imprint of Thatcherism far more than any traces of socialist doctrine. This would strongly suggest that the impact and legacy of the New Right went far beyond the end of Conservative rule and continued to wield influence into the new century, despite the Conservative Party being banished from national office. This was evident by the fact that Blair’s Labour government pledged to “govern as New Labour”, which in practice entailed moderate politics that explicitly rejected past socialist doctrines, and by adhering to the political framework and narrative established during the Thatcher period of New Right hegemony. This included an acceptance of the privatisation of former state-owned industries, tougher restrictions to trade union powers, markedly reduced levels of government spending and direct taxation, and overall, far less state intervention in comparison to the ‘years of consensus’ that existed between approximately 1945-75 (shaped by the crisis experience of World War Two). Most of these policies had been strongly opposed by Labour during the 1980s, but under New Labour they were now pragmatically accepted (for largely electoral and strategic purposes). Blair and his Chancellor Gordon Brown tinkered around the edges with some progressive social reforms and there were steadily growing levels of tax and spend in his later phase in office, but not on the scale of the past, and the New Right neoliberal ‘settlement’ remained largely intact throughout thirteen years of Labour in office. Indeed, Labour’s truly radical changes were primarily at constitutional level; featuring policies such as devolution, judicial reform (introduction of the Supreme Court), various parliamentary reforms (House of Lords), Freedom of Information legislation, as well as key institutional changes such as Bank of England independence. The nature of this reforming policy agenda could be seen to reflect the reality that following the New Right’s ideological and political victories of the 1980s, New Labour had to look away from welfarism and political economy for its major priorities. Conservative modernisation (1997 onwards) Given the electoral success of Tony Blair and New Labour from 1997 onwards, the obvious challenge for the Conservatives was how to respond and readjust to unusual and indeed unprecedented circumstances. Historically referred to as ‘the natural party of government’, being out of power for a long time was a situation the Conservatives were not used to. However, from the late 1990s onwards, party modernisers broadly concluded that it would be a long haul back, and that to return to government the party would have to sacrifice some, and perhaps all, of its increasingly unpopular New Right political baggage. This determinedly realistic mood was strengthened by a second successive landslide defeat to Blair in 2001, and a further—albeit less resounding—defeat in 2005. Key and emerging figures in this ‘modernising’ and ‘progressive’ wing of the party included David Cameron, George Osborne and Theresa May, none of whom had been MPs prior to 1997 (i.e., crucially, they had no explicit connections to the era of New Right hegemony) and all of whom would take on senior governmental roles after 2010. Such modernisers accepted that the party required a radical overhaul in terms of both image and policy-making, and in global terms were buoyed by the victory of ‘compassionate’ conservative George W. Bush in the US presidential election in late 2000. Consequently, ‘Compassionate Conservatism’ became an increasingly used term among such advocates of a new style of Conservative policy-making (see Norman & Ganesh, 2006).[8] My doctoral thesis analysed in some depth precisely what the post-1997 British Conservative Party did in relation to various policy fronts connected to this ‘compassionate’ theme, most notably initiating a revived interest in the evolution of innovative social policy such as free schools, NHS reform, and the concept of ‘The Big Society’. This was in response to both external criticism and self-reflection that such policy emphasis and focus had been frequently neglected during the party’s eighteen years in office between 1979 and 1997.[9] Yet the New Right legacy continued to haunt the party’s identity, with many Thatcher loyalists reluctant to let go of it, despite feedback from the likes of party donor Lord Ashcroft (2005)[10] that ‘modernisation’ and acceptance of New Labour’s social liberalism and social policy investment were required if the party was to make electoral progress, while ultimately being willing to move on from the (albeit triumphant) past. Overview of The New Right and post-2008 events: (1) The global crash (2) austerity (3) Brexit (4) the pandemic During the past few decades of British and indeed global politics, the New Right’s core principles of the small state and limited government intervention have remained clearly in evidence, with its influence at its peak and most firmly entrenched in various western governments during the 1980s and 90s. However, within the more contemporary era, this legacy has been fundamentally rocked and challenged by two major episodes in particular, namely the economic crash of 2007–8, and more recently the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Both of these crises have featured a fundamental rebuke to the New Right’s established solutions as aligned with the culture of the reduced state, as had been cemented in the psyche of governance and statecraft within both Britain and the USA for several decades. In the context of the global economic slump, the immediate and instinctive reaction of Brown’s Labour government in Britain and Barack Obama’s Democrat administration in the USA was to focus on a primary role for the state to intervene and stimulate economic recovery, which entailed that large-scale ‘Keynesian’ government activity made a marked comeback as the preferred means of tackling it. While both such politicians were less ideologically wedded to the New Right pedigree (since they were attached to parties traditionally more of the liberal left), this scenario nevertheless marked a significant crossroads for the New Right’s legacy for global politics. However, once the dust had settled and the economic situation began to stabilise, the post-2010 austerity agenda that emerged in the UK (as a longer-term response to managing the global crash) provided New Right advocates with an opportunistic chance to reassert its former hegemony, given the setback to its influence in the immediate aftermath of 2008. Although Prime Minister David Cameron rejected criticism that austerity marked a reversion to harsh Thatcherite economics, having repeatedly distanced himself from the former Conservative Prime Minister since becoming party leader in 2005, there were certainly similarities in the emphasis on ‘balancing the books’ and reducing the size of government between 2010-15. Cameron argued this was not merely history repeating itself, and sought to distinctively identify himself as a more socially-oriented conservative who embraced an explicit social conscience that differed from the New Right’s primarily economic focus, as evident in his ‘Big Society’ narrative entailing a reduced state and more localised devolution and voluntarism (yet which failed to make his desired impact).[11] Cameron argued that “there was such a thing as society” (unlike Thatcher’s quote from 1987)[12], yet it was “not the same as the state”. [13] Following Cameron’s departure as Prime Minister in 2016, the issue that brought him down, Brexit, could also be viewed from the New Right perspective as a desirable attempt to reduce, or ideally remove, the regulatory powers of a European dimension of state intervention, with the often suggested aspiration of post-Brexit Britain becoming a “Singapore-on-Thames” that would attract increased international capital investment due to lower taxes, reduced regulations and streamlined bureaucracy. It was perhaps no coincidence that many of the most ardent supporters of Brexit were also those most loyal to the Thatcher policy legacy that lingered on from the 1980s, representing a clear ideological overlap and inter-connection between domestic and foreign policy issues.[14] On this premise, the New Right’s influence dating from its most hegemonic decade of the 1980s certainly remained. However, from a UK perspective at least, the Covid-19 pandemic arguably ‘heralded the further relative demise of New Right influence after its sustained period of hegemonic ascendancy’.[15] This is because, in a similar vein to the 2007–8 economic crash, the reflexive response to the global pandemic from Boris Johnson’s Conservative government in the UK and indeed other western states (including the USA), was a primarily a ‘statist’ one. This was evidently the preferred governmental option in terms of tackling major emergencies in the spheres of both the economy and public health, and was perhaps arguably the only logical and practical response available in the context of requiring such co-ordination at both a national and international level, which the free market simply cannot provide to the same extent. Having said that, during the pandemic there was evidence of some familiar neoliberal ‘public-private partnership’ approaches in the subcontracting-out of (e.g.) mask and PPE production, lateral flow tests, vaccine research and production, testing, or app creation, which suggests Johnson’s administration sought to put some degree of business capacity at the heart of their policy response. Nevertheless, the revived interventionist role for the state will possibly be difficult to reverse once the crisis has subsided, just as was the case in the aftermath of World War Two. Whether this subsequently creates a new variant of state-driven consensus politics (as per the UK 1945-75) remains to be seen, but in the wake of various key political events there is clear evidence that the New Right’s legacy, while never being eradicated, certainly seems to have been diluted as the world progresses into the 2020s. How the post-pandemic era will evolve remains uncertain, and in their policy agendas various national governments will seek to balance both the role of the state and the input of private finance and free market imperatives. The nature of the balance remains a matter of speculation and conjecture until we move into a more certain and stable period, yet it would be foolish to write off the influence of the New Right and its resilient legacy completely. [1] Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, (1944) [2] Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, (1962) [3] Ben Williams, The Evolution of Conservative Party Social Policy, (2015) [4] BBC ON THIS DAY | 2 | 1997: Labour routs Tories in historic election (2nd May 1997) [5] Andrew Gamble, The Crisis of Conservatism, New Left Review, (I/214, November–December 1995) [6] Michael Oakeshott, On Human Conduct, (1975) [7] Rob Baggott, ‘Conservative health policy: change, continuity and policy influence’, cited in Hugh Bochel (ed.), The Conservative Party and Social Policy, (2011), Ch.5, p.77 [8] Jesse Norman & Janan Ganesh, Compassionate conservatism- What it is, why we need it (2006), https://www.policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/compassionate-conservatism-june-06.pdf [9] Ben Williams, Warm words or real change? Examining the evolution of Conservative Party social policy since 1997 (PhD thesis, University of Liverpool), https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/11633/1/WilliamsBen_Apr2013_11633.pdf [10] Michael A. Ashcroft, Smell the coffee: A wake-up call for the Conservative Party, (2005) [11] Ben Williams, The Big Society: Ten Years On, Political Insight, Volume: 10 issue: 4, page(s) 22-25 (2019) [12] Margaret Thatcher, interview with ‘Woman’s Own Magazine’, published 31 October 1987. Source: Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689 [13] Society and the Conservative Party - BBC News (9th January 2017) [14] Ben Williams, Brexit: The Links Between Domestic and Foreign Policy, Political Insight, Volume: 9 issue: 2, page(s): 36-39 (2018) [15] Ben Williams, The ‘New Right’ and its legacy for British conservatism, Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021) by Sean Seeger

What is the relationship of queer theory to utopianism?