by Lenon Campos Maschette

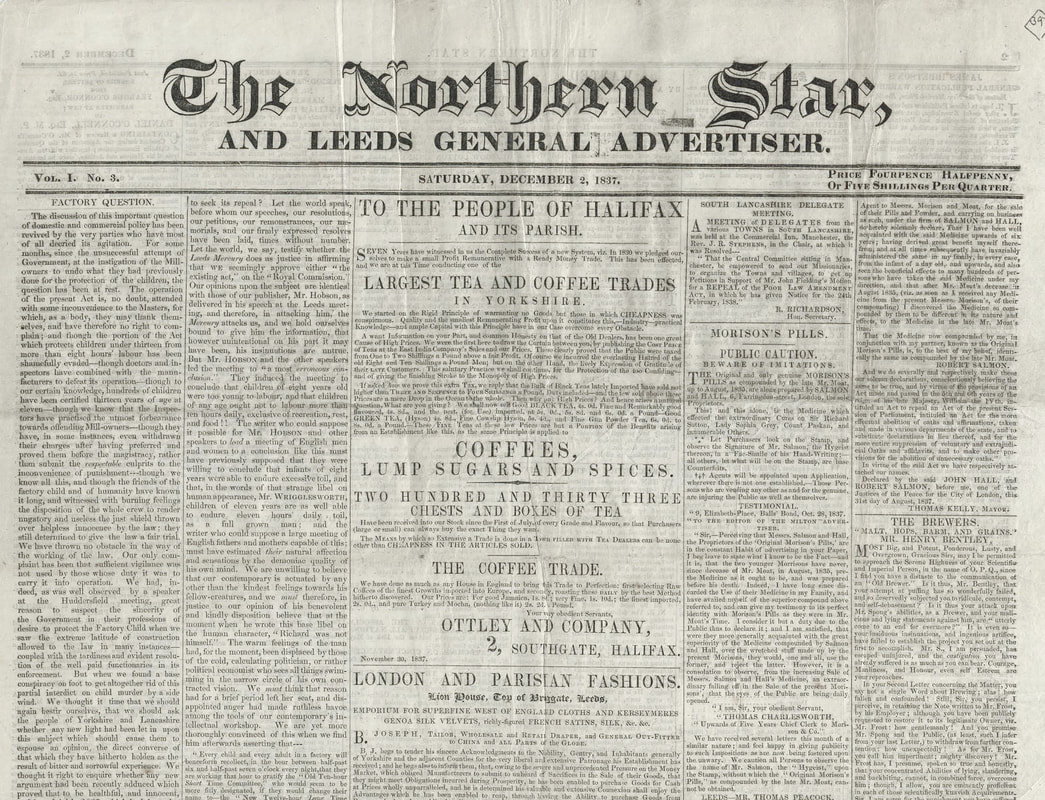

Over the past few centuries, the concept of civil society has shifted a few times to the centre of political debate. The end of the 20th century witnessed one of these moments. From the 1980s, civil society resurfaced as a central political idea, an important conceptual tool to address all types of social and political problems as well as describe social formations. At the end of the last century, a general criticism of the state and its inability to solve key social problems and the search for a ‘post-statist’ politics were problems shared by several countries that allowed the civil society debate to spread globally.[1]

In Britain, ideologies of the right had an important role in this movement. From the 1980s, all the discussions around community and citizen participation have to be analysed, at least in part, within the context of how the nature and function of the state were being reshaped, especially through the changes proposed by right-wing intellectuals and politicians. This tendency is even more noticeable within the British Conservative Party. In one of the most important works on the British Conservative Party and civil society, E. H. H. Green argues that the Conservative Party’s state theory throughout the 20th century was more concerned with the effectiveness of civil society bodies than with the role of the state.[2] Therefore, it is a long tradition that was continued and reinforced by Thatcher’s leadership. As I argued in another work, the Thatcher government redefined the concept of citizenship and placed civil society at the centre of its model of citizenship.[3] In this new article, I want to compliment that and argue that civil society had vital importance in Thatcher’s project. From this perspective, the Thatcher government redefined the idea of civil society, regarded as the space par excellence for citizenship—at least in the way Thatcherism understood it. Thatcherism attributed to civil society and its institutions a central role in the socialisation of individuals and the transmission of traditional values. It was the place par excellence of individual moral development and, consequently, citizenship. Thatcherism and civil society The Conservative Party never abandoned the defence of civil associations as both important institutions to deliver public services and essential spaces for maintaining and transmitting shared values. Throughout the post-WW2 period, the Party continuously emphasised the importance of the diversity of voluntary associations, and as a response to the growing dissatisfaction with statutory welfare, support for more flexible, dynamic, and local voluntary provision became part of its 1979 manifesto. As already mentioned, civil society had virtually disappeared from the public debate and Thatcher herself rarely used the term ‘civil society’. However, the idea had a central role within Thatcherism. As the article will show, the Conservatives were constantly thinking about the intermediary structures between individuals and the state, and from these reflections we can try to comprehend how they saw these institutions, their roles, and their relationships. According to the Conservatives, civil society was being threatened by a social philosophy that had placed the state at the centre of social life to the detriment of communities. In fact, civil society had not disappeared, but was experiencing profound changes. In a more affluent and ‘post-materialistic’ society, individuals had turned their attention from first material needs to identities, fulfilment, and greater quality of life. Charities and religious associations had also changed their strategies and came close to the approach and methods of secular and modern voluntary associations, loosening their moralistic and evangelical language and adopting a more political and socially concerned discourse. These are important transformations that are the basis of how the Thatcher government linked the politicisation of these institutions with the demise of civil society. Thatcher always made clear that voluntary associations and civil institutions were central to her ‘revolutionary’ project. The Conservatives under Thatcher regarded the civil institutions as the best means to reach more vulnerable people and the perfect space for participation and self-expression.[4] The neighbourhood, this smallest social ‘unit,’ was more personal and effective than larger and more bureaucratic bodies. Furthermore, civil society empowered individuals by giving them the opportunity to participate in local communities and make a difference. It is noteworthy that Thatcher’s individualism was not synonymous with an atomised and isolated individual. Thatcher did not have a libertarian view about the individuals. As she argued to the Greater Young Conservatives group, ‘there is not and cannot possibly be any hard and fast antithesis between self-interest and care for others, for man is a social creature … brought up in mutual dependence.’[5] According to her, there was no conflict between her ‘individualism and social responsibility,’[6] as individuals and community were connected and ‘personal efforts’ would ‘enhance the community’, not ‘undermine’ it.[7] She believed in a community of free and responsible individuals, ‘held together by mutual dependence … [and] common customs.’[8] Working in the local and familiar, within civil associations and voluntary bodies, individuals, in seeking their own purposes and goals, would also achieve common objectives, discharge their obligations to the community and serve their fellows and God.[9] And here is the key role of civil and voluntary bodies. They were responsible for guaranteeing traditional standards and transmitting common customs. By participating in these associations, individuals would achieve their own interests but also feel important, share values, strengthen social ties, and create a distinctive identity. Thatcherites believed that voluntary associations, charities, and civil institutions had a central position in the rebirth of civic society. These conceptions partly resonated with a conservative tradition that recognised the intermediated structures as institutions responsible for balancing freedom and order. For conservatives, civil institutions and associations have always played a central role within civil society as institutions responsible for socialising and moralising individuals. From the Thatcherite perspective, these ‘little platoons’—a term formulated by Edmund Burke, and used by conservatives such as Douglas Hurd, Brian Griffiths,[10] and Thatcher herself to qualify local associations and institutions—provided people a space to develop a sense of community, civic responsibility, and identity. Therefore, Thatcher and her entourage believed that civil society had many fundamental and intertwined roles: it empowered individuals through participation; it developed citizenship; it was a repository of traditions; it transmitted values and principles; it created an identity and social ties; and it was a place to discharge individuals’ obligations to their community and God. The state—not Thatcherism, nor indeed the market—isolated individuals by stepping into civil society spaces and breaking apart the intermediary institutions.[11] In expanding beyond its original attributions, the state had eclipsed civil associations and institutions. Centralisation and politicisation were weakening ‘mediating structures,’ making people feel ‘powerless’ and depriving individuals of relieving themselves from ‘their isolation.’[12] It was also opening a space for a totalitarian state enterprise. While the state was creating an isolated, dependent, and passive citizenry, the new social movements were politicising every single civil society space, fostering divisiveness and resentment. The great issue here was politicisation. Civil and local spaces had been politicised. The local councils were promoting anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-homophobic agendas, local government and trade unions were encouraging riots and operating ‘to break, defy, and subvert the law’[13] and the Church was ‘failing the people of England.’[14] Neoconservatives[15] drew attention to both the intervention and politicisation from the state but also from social movements such as feminism. As shown earlier, civil society dynamics had changed and new and more politicised movements emerged. John Moore, a minister and another long-term member of Thatcher’s cabinet, complained that modern voluntary organisations changed their emphases from service groups to pressure groups.[16] That is the reason why Thatcher, in spite of increasing grants to the voluntary sector, carefully selected those associations with principles related to ‘self-help and enterprise,’ that encouraged ‘civic pride’ while also discouraging grants to institutions previously funded by left-wing councils.[17] The state and the new social movements had politicised and dismantled civil society spaces, especially the conservatives' two most important civil institutions: the family and the Church. Thatcherism placed the family at the centre of civil society. Along with the ‘surrounding community of friends and neighbours,’ the family was a key institution to ‘individual development.’[18] This perspective dialogued with a conservative idea that came directly from Burke and placed the family at the core of civil society. From a Burkean perspective, the family was an essential institution for civilisation as it had two fundamental roles: acting as the ‘bulwarks against tyranny’ and against the ‘perils of individualism.’[19] The family was important as the first space of socialisation and affection and, consequently, the first individual responsibility. Within the family, moral values were kept and transmitted through generations, preventing degeneration and dependence. Thatcher’s government identified the family as the ‘very nursery of civil virtue’[20] and created the Family Policy Group to rebuild family life and responsibility. The family also had a decisive role in checking the state authority. Along with neoconservatives, Thatcherites believed that the welfare state and ‘permissiveness’ had broken down the family and its core functions. From this perspective, the most important civil institution had been corrupted by the state and the new social movements. If Thatcherism dialogued with neoliberalism and its criticism of the state, it was also influenced by conservative ideas of civil society and neoconservative arguments against the new social movements and the welfare state. Despite some tensions, Thatcherism was successful in combining neoliberal and neoconservative ideas. The other main civil institution was the Church. Many of Thatcher’s political convictions were moral, rooted in puritan Christian values nurtured during her upbringing. Thatcher and many of her allies believed that Christianity was the foundation of British society and its values had to be widely shared. The churches were responsible for exercising ‘over [the] manners and morality of the people’[21] and were the most important social tool to moralise individuals. Only their leaders had the moral authority ‘to strengthen individual moral standards’[22] and the ‘shared beliefs’ that provide people with a moral framework to prevent freedom to became something destructive and negative.[23] Thus, the conservatives had the goal of depoliticising civil society. It should be a state- and political-free space. Thatcher’s active citizen was an apolitical one. The irony is that the Thatcher administration made these institutions even more dependent on state funding. Thatcherism was incapable of comprehending the new dynamics of civil institutions. The diverse small institutions, mainly composed of volunteer workers, had been replaced by larger, more bureaucratic and professionalised ones closely related to the state. If the state and, consequently, politicians could not moralise individuals—which, in part, explains the lack of a moral agenda in the period of Thatcher’s government, a fact so criticised by the more traditional right, since ‘values cannot be given by the state or politician,’[24] as she proclaimed in 1978—other civil society institutions not only could, but had a duty to promote certain values. The Thatcher government and communities From the mid-1980s, the Conservative Strategy Group advised the party to emphasise the idea of a ‘good neighbour’ as a very distinct conservative concept.[25] The Conservative Party turned its eyes to the issue of communities and several ministers started to work on policies related to neighbourliness. At the same time, Thatcher’s Policy Unit also started thinking of ways to rebuild ‘community infrastructure’ and its voluntary and non-profit organisations. The civil associations more and more were being seen by the government as an essential instrument in changing people’s views and beliefs.[26] As we have seen, it was compatible with the Thatcherite project. However, it was also a practical answer to rising social problems and an increasingly conservative perception, towards the end of the 1980s, that Thatcher’s administration failed to change individual beliefs and civil society actors, groups, and institutions. And then, we begin to note the tensions between Thatcherite ideas and their implications for the community. Thatcherites believed in a community that was first and foremost moral. The community was made up of many individuals brought up by mutual dependence and shared values and, as such, carrying duties prior to rights. That is why all these civic institutions were so important. They should restrain individual anti-social behaviour through the wisdom of shared ‘traditional social norms that went with them.’[27] The community should set standards and penalise irresponsible behaviour. A solid religious base was therefore so important to the moral civil society framework. And here Thatcher was always very straightforward that this religious basis was a Christian one. Despite preaching against state intervention, Thatcher was clear about the central role of compulsory religious education to teach children ‘the difference between right and wrong.’[28] In order to properly work, these communities and its civil institutions should have their authority and autonomy restored to maintain and promote their basic principles and moral framework. And that is the point here. The conservative ‘free’ communities only could be free if they followed a specific set of values and principles. During an interview in May 2001—among rising racial tensions that lead to serious racial disturbances over that year’s spring and summer—Thatcher argued that despite supporting a society comprised of different races and colours, she would never approve of a ‘multicultural society,’ as it could not observe ‘all the best principles and best values’ and would never ‘be united.’[29] Thatcher was preoccupied with immigration precisely because she believed that cultural issues could have negative long-term effects. As she said on another occasion, ‘people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.’[30] Different individuals would work together and keep themselves together only if they shared some basic principles and beliefs. Thatcher’s community was based on common tradition, not consent or contract. Conservatives believed that shared values were essential for social cohesion. That is why a multicultural society was so dangerous from her perspective. Moreover, there is also another implication here. Multiculturalism not only needed to be repulsed because it was regarded as divisive, but also because it presupposes that all cultures have equal value. It was not only about sharing the same values and principles, but also about sharing the right values and principles. And for the conservatives, the British and Christian traditions were the right ones. That is why Christian religious education should be compulsory for everybody, regardless of their ethnic and cultural background. In part, it explains the Thatcher administration’s long fight against local councils and authorities that supported multiculturalism and anti-racist movements. They were seen as a threat to cultural and traditional values as well as national sovereignty. In addition to responding many times with brutal police repression to the 1981 riots—which is in itself a strong state intervention—the government also released resources for urban regeneration and increased the budget of ‘ethnic projects’ in order to control these initiatives. The idea was to shape communities in a given way and direction and create tools for the community to police themselves. The government was seeking ways to change individual attitudes that, according to the Conservatives, were at the root of social problems in the inner cities. Rather than being the consequence of social problems, these attitudes, they argued, were caused by cultural and moral issues, especially in predominantly black communities.[31] In encouraging moderate black leaders, the government was trying to foster black communities that would behave as British middle-class neighbourhoods.[32] Thatcher’s government also tried to shape communities through business enterprises and market mechanisms. In the late 1980s, her government started a bold process of community refurbishment that aimed to revitalise what were regarded as deprived areas. The market was also seen as a part of civil society and a moralising space that encouraged good behaviour. Thatcher’s relationship with the family, the basis of civil society, was also problematic. The Conservatives had a very traditional conception of family. The family was constituted by a heterosexual married couple. If Thatcherites accused new social movements of imposing their worldview on the majority, Thatcher’s government tried to prescribe a ‘natural’ view of family that excluded any type of distinct formation. Furthermore, despite presiding over a decade that saw a rising expansion of women's participation in the workplace and education, Thatcher advanced an idea of community that was based on women's caring role within the family and the neighbourhood. Finally, the Church, regarded as the most important source of morality, was, at first, viewed as a natural ally, but soon would become a huge problem for her government. As with many established British institutions, according to the Conservatives, the Church had been captured by a progressive mood that had politicised many of its leaders and diverted the Church's role on morality. The Church was failing Britain since it had abdicated its primary role as a moral leader. It was also part of a broader attack on the British establishment. Thatcher would prefer to align her government with religious groups that performed a much more ‘valuable role’ than the established Church.[33] The tensions between the Thatcher government's ideas and policies—which blended neoliberal and neoconservative approaches—and its results in practice would lead to reactions on both left and right-wing sides. If Thatcher herself realised that her years in office had not encouraged communities’ growth, the New Labour and the post-Thatcher Conservative Party would invest in a robust communitarian discourse. Tony Blair's Party would use community rhetoric to emphasise differences from Thatcherism, whereas the rise of ideas that focused on civil society, such as Compassionate Conservatism, Civic Conservatism, and Big Society, would be a Conservative response to the Thatcher's 1980s. Conclusion Conventionally, conservatives have treated civil society as a vehicle to rebuild traditional values, a fortress against state power and homogenisation that involved the past, the present and the future generations. Thatcher believed that a true community would be close to the one where she spent her childhood. A small community, composed by a vibrant network of voluntary bodies free from state intervention, in which apolitical and responsible citizens would be able to discharge their religious and civic obligations through voluntary work. These obligations resulted from religious values and individuals' mutual physical and emotional dependence, which imposed responsibilities prior to their rights, derived from these duties rather than from an abstract natural contract. Therefore, the Thatcherite community was, above all, a moral community. Accordingly, it was based on a narrow set of values and principles that was based on conservative British and Christian traditions. In a complex contemporary world of multicultural societies, it is difficult not to see Thatcher's community model as exclusionary and authoritarian. Despite her conservative ideas about neighbourhoods, her government seems to have encouraged even more irresponsible behaviour and community fragmentation. Thatcher seems not to have been able to identify the problems that economic liberalisation policies and strong individualistic rhetoric could cause to the community. Here, the tensions between her neoliberal and neoconservative positions became clearer. As she recognised during an interview, ‘I cut taxes and I thought we would get a giving society and we haven’t.’[34] To conclude, it is interesting to note that the civil society debate emerged in the UK with and against Thatcherism. The argument based on the revitalisation of civil society was used by both left and right-wingers to criticise the Thatcher years.[35] New Labour’s emphasis on communities, post-Thatcher conservatism’s focus on civil society, the emergence of communitarianism and other strands of thought that placed civil society at the centre of their theories; despite their differences, all of them looked to the community as an answer for the 1980s and, at least in part, its emphasis on the free market and individualism. On the other hand, as I have tried to show, Thatcherism was already working on the theme of community and raised many of these issues during the years following her fall. The idea of civil society as the space par excellence of citizenship and collective activities, as the place to discharge individual obligations and as a site of a strong defence against arbitrary state power, were all themes advanced by Thatcherism that occupied a lasting space within the civil society debate. Thatcherism thus also influenced the debate from within, not only through the reaction against its results, but also directly promoting ideas and policies about civil society. [1] Jean Cohen and Andrew Arato, Civil Society and Political Theory (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1997), 71-72. [2] E.H.H. Green, Ideologies of Conservatism. Conservative Political Ideas in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 278. [3] Lenon Campos Maschette, 'Revisiting the concept of citizenship in Margaret Thatcher’s government: the individual, the state, and civil society', Journal of Political Ideologies, (2021). [4] Margaret Thatcher, Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture (‘Liberty and Limited Government 11 January 1996). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/108353. [5] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to Greater London Young Conservatives (Iain Macleod Memorial Lecture, ‘Dimensions of Conservatism’ 4 July 1977). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103411. [6] Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (London: Harper Collins, 1993), 627. [7] Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Party Conference, 14 October 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation document 107352: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107352. [8] Margaret Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (‘I BELIEVE – a speech on Christianity and politics’ 30 March 1978). Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103522. [9] Thatcher, The Moral Basis of a Free Society. Op. Cit. [10] Douglas Hurd had several important roles during Thatcher’s administration, including Home Office. Brian Griffiths was the chief of her Policy Unit from the middle 1980s and one of her principal advisors. [11] Michael Alison, ‘The Feeding of the Billions’, in Michael Alison and David Edward (eds) Christianity & Conservatism. Are Christianity and conservatism compatible? (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990), 206-207; Brian Griffiths, ‘The Conservative Quadrilateral’, Alison and Edward, Christianity & Conservatism, 218; Robin Harris, Not for Turning (London: Corgi Books. 2013), 40. [12] Griffiths, Christianity & Conservatism, 224-234. [13] Margaret Thatcher. Speech to Conservative Party Conference 1985. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106145. [14] John Gummer, apud Martin Durham, ‘The Thatcher Government and “The Moral Right”’, Parliamentary Affair, 42 (1989), 64. [15] American neoconservatives such as Charles Murray, George Gilder, Lawrence Mead, Michael Novak, etc., worked on the social, cultural, and moral consequences of the welfare state and the ‘long’ 1960s. They were also much more active in writing on citizenship issues. These authors had a profound influence on Thatcher’s Conservative Party through the think tanks networks. Murray and Novak, for instance, even attended Annual Conservative Party conferences and visited Thatcher and other Conservative members’ Party. [16] Timothy Raison, Tories and the Welfare State. A history of Conservative Social Policy since the Second World War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990), 163. [17] Geoffrey Finlayson, Citizen, State and Social Welfare in Britain 1830 – 1990 (Oxford, 1994), 376. [18] Douglas Hurd, Memoirs (London: Abacus, 2003), 388. [19] Richard Boyd, ‘The Unsteady and Precarious Contribution of Individuals’: Edmund Burke's Defence of Civil Society’. The Review of Politics, 61 (1999), 485. [20] Margaret Thatcher, Speech to General Assembly to the Church of Scotland, 21 May 1988. Margaret Thatcher Foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/107246. [21] Douglas Hurd, Tamworth Manifesto, 17 March 1988, London Review of Books: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v10/n06/douglas-hurd/douglas-hurds-tamworth-manifesto. [22] Douglas Hurd, article for Church Times, 8 September 1988. THCR /1/17/111B. Churchill Archives, Churchill College, Cambridge University. [23] Thatcher, Speech at St. Lawrence Jewry (1978), Op. Cit. [24] Margaret Thatcher, apud Matthew Grimley. Thatcherism, Morality and Religion. In: Ben Jackson; Robert Saunders (Ed.). Making Thatcher’s Britain. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2012), 90. [25] Many meetings emphasised this issue throughout 1986. CRD 4/307/4-7. Conservative Party Archives, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University. [26] ‘Papers to end of July’, 18 June 1987. PREM 19/3494. National Archives, London. [27] Edmund Neill, ‘British Political Thought in the 1990s: Thatcherism, Citizenship, and Social Democracy’, Mitteilungsblatt des Instituts fur soziale Bewegungen, 28 (2002), 171. [28] Margaret Thatcher, ‘Speech to Finchley Inter-church luncheon club’, 17 November 1969. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/101704. [29] Margaret Thatcher, interview to the Daily Mail, 22 May 2001, apud Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher, Vol. III Herself Alone (London: Penguin Books, 2019), 825. [30] Margaret Thatcher, TV Interview for Granada World in Action ("rather swamped"), 27 January 1978. Margaret Thatcher foundation: https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103485. [31] Oliver Letwin blocked help for black youth after 1985 riots. The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/dec/30/oliver-letwin-blocked-help-for-black-youth-after-1985-riots. [32] Paul Gilroy apud Simon Peplow. Race and riots in Thatcher’s Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 213. [33] Grimley, Op. Cit., 92. [34] Thatcher’s interview to Frank Field, apud Eliza Filby. God & Mrs Thatcher. The battle for Britain’s soul (London: Biteback, 2015), 348. [35] Neill, Op. Cit., 181. by Joanne Paul

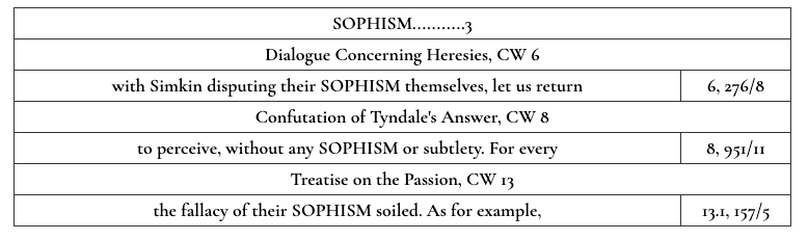

A lot can be said about the relationship between utopianism and ideology, and Gregory Claeys covered much of it in his comprehensive and detailed contribution to this blog.[1] As with all discussions of utopianism, however, participants cannot help but acknowledge the roots of the concept in the originator of the term, Thomas More’s masterfully enigmatic Utopia (full title: On the Best State of the Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia). Whether it was More himself who coined the term (it has been suggested it was in fact Erasmus), and acknowledging the longer (and global) history of imagined ideal states, any consideration of utopianism must at some point trace itself to More’s sixteenth-century text. This can make for some awkward anachronistic connections, especially for anyone concerned particularly with the importance of contextualism in the analysis of historic texts (as I am). Even the question of whether there is an ‘ideology’ present in More’s text can immediately be countered with the charge of anachronism. This is, of course, an issue with the term itself. However, much like we might acknowledge utopias (or utopian thinking) prior to 1516, we might also entertain the suggestion that ideology as a concept (if not a term) might have existed prior to the Enlightenment, and that various contemporary ideologies might also have their roots in the Renaissance, even if More would have been perplexed—but likely intrigued—by the term itself. The purpose of this piece, then, is to explore two interrelated questions. First, whether we can think about ideology and Utopia without giving ourselves entirely over to anachronism and thus a reading of the text that cannot be substantiated. Second, in a similar vein, to test the waters with a variety of ‘ideologies’ with which Utopia has been associated: republicanism, liberalism, totalitarianism/authoritarianism, socialism/communism, and, of course, utopianism. In this ‘testing’, the first criteria will be consistency within the text itself, but in establishing this, I will be reading the text in the context of More’s times and other works. Utopia is too frequently read as a stand-alone text despite—or perhaps because of—More’s substantial oeuvre. It is an intentionally ambiguous work, which is why so many different and even opposed ideologies can be read into it. In order to test the legitimacy of these readings, we must understanding Utopia in the context of More’s work more widely. A short caveat: none of this, of course, precludes the use of Utopia as an inspiration or foundation for a variety of ideological arguments, and Claeys has repeatedly made an impassioned and vitally important argument for the role of utopian thinking in meeting the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century (along with another contribution to this blog by Mathias Thaler)[2]. Political theorists and philosophers have—often very good—reasons for playing harder and faster with the ‘rules’ of historical contextualism (for more on this, see in particular the work of Adrian Blau).[3] There are, however, also good reasons to want to be attentive to the particularities of an utterance in its historical context, which I will not rehearse here, but which I hope are evident in what follows. Ideology and Utopia Does the idea of ‘ideology’ fit with a sixteenth-century intellectual mindset? More was not unfamiliar with the notion of ‘-isms’, often seen as the shorthand for identifying ideologies (though not in the explicitly modern sense).[4] Most of these ‘-isms’ were religious, not just less ‘ideological’ words like baptism, but those that more accurately fit the definition of a ‘system of beliefs’ such as ‘Judaism’, which More used in his Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer (1532).[5] It was the Reformation, Harro Höpfl has noted, which saw the widespread use of ‘isms’ to refer to ‘theological or religious positions considered heretical, and also to refer to the doctrines of various philosophical schools’.[6] Indeed More used the term ‘sophism’ (see the excerpt from the concordance above) in a way that arguably had ideological connotations, and not expressly or necessarily religious ones.[7] That being said, Ideology’s association with political ideas as wholly distinct from religious ones might have not squared with More’s worldview. Any religion can fit the definition of an ‘ideology’ and religious ideas permeated every aspect of More’s world, including—and especially—politics. The way in which Utopia can and has been read as an especially secular text is part of what makes it an enduringly popular text to study, certainly more than More’s other—obviously (and vehemently) religious—writings. There is something attractively secular about More’s pre-Christian island, which is based more obviously on classical pagan influences than medieval Christian ones. For this reason, it is temptingly easy to read a series of ideologies into this short book. The interesting question for a historian like myself becomes whether these were ideas available and attractive to More himself. Republicanism The island of Utopia is obviously and expressly a republic, and the neo-classical humanist More would have fully understood what this entailed. Both books of the text articulate, as Quentin Skinner has demonstrated, arguments for a Ciceronian vita activa, on which republicanism is based.[8] Although each Utopian city is ruled by a princeps, they are elected, and rule in consultation with an assembly of elected ‘tranibors’. The island as a whole is ruled by a General Council, made up of representatives elected from each city. This description of Utopia is framed by a discussion about the merits of the active life in the context of a monarchy, echoing similar discussions in Isocrates, Cicero, Erasmus, and others.[9] Does this align Utopia with ‘republicanism’ as an ideology? Certainly, the text deserves an important place in the development of that ideology from its ‘Athenian and Roman roots’, especially when read in the context of More’s other writings, which express a conciliarism that clearly has overlaps with classical republicanism. In his Latin Historia Richardi Tertii, More writes that parliament, which he calls a senatus, has ‘supreme and absolute’ authority, and in his religious polemics, he is keen to draw a connection between the parliament and the General Council.[10] The latter, he writes, has the power to depose the Pope and, whereas the Pope’s primacy can be held in doubt, ‘the general councils assembled lawfully… the authority thereof ought to be taken for undoubtable’.[11] Both parliament and the General Council are authorised representatives of the whole community, whether the church or the realm.[12] More also expresses ideas in line with what has come to be known as ‘republican liberty’: ‘non-domination’ or ‘that freedom within civil associations’, impling the lack of an ‘arbitrary power’ which would reduce ‘the status of free-man to that of slaves’.[13] In his justification of the importance of law, More writes, that ‘if you take away the laws and leave everything free to the magistrates… they will rule by the leading of their own nature… and then the people will be in no way freer, but, by reason of a condition of servitude, worse’.[14] This aligns with the Renaissance view of tyranny as ruling according to one’s own willful passions, rather than right reason. More certainly saw unfreedom in the rule of licentia (or license) over reason.[15] This could be found both in the rule of a single tyrant and in the anarchy of pluralism, a situation he feared would arise from Lutheranism.[16] As such, a firmly established structure of self-government, like that in Utopia, was the ideal way to ensure his notion of freedom, one that was largely in accordance with the republican tradition. Liberalism This is in contrast with notion of freedom advanced in Utopia by the character Raphael Hythloday, which we might think of as more in line with a ‘liberal’ perspective. He does not want to ‘enslave’ himself to a king and prefers to ‘live as I please’, certainly more ‘license’ than ‘liberty’ in More’s perspective.[17] There is an inherent contradiction between republican and liberal notions of liberty. In so far as More can be said to express something of the former, he is deeply against the latter. Individualism sits at the heart of liberalism; it is, as Michael Freeden and Marc Stears have suggested (though not without qualification), ‘an individualist creed’, seeking to enshrine ‘individual rights, social equality, and constraints on the interventions of social and political power’.[18] Liberalism was a product of the Enlightenment, and so More could not properly be said to be its opponent, but he did powerfully critique what we might see as its nascent constitute parts. In his other works, More often repeats a distinction between the people (populus) and ‘anyone whatever’ (quislibet), to the derision of the authority of the latter.[19] This lies at the heart of his fear of anarchy and Lutheranism, which he accuses of transferring ‘the authority of judging doctrines… from the people and deliver[ing] it to anyone whatever’.[20] In Utopia, we can see this critique of proto-individualism in his central message about pride, which he (with Augustine) takes to be the root of all sin, as it necessarily cuts across the bonds that should unite the populus. Pride is not just self-love, but self-elevation, a form of comparative arrogance that seeks to mark one out from others (a sin he associates with the scholastics, vice-ridden nobility, Lutherans, and indeed most of his opponents). Utopia has thus been read as a repressive regime which quashes—rather than upholds—freedom. This is from the perspective of post-Enlightenment liberalism, and takes Utopia perhaps more literally than it is meant. Read as a critique of the pride which we might associate with a sort of proto-individualism, it offers a powerful critique of an ideology which is—it must be acknowledged—in need of a reassessment. Totalitarianism/Authoritarianism It is for its anti-liberal qualities that Utopia has ended up associated with some of the darkest ideologies of the 20th century. More’s biographer, Richard Marius, called his views about education—certainly present in Utopia—‘an authoritarian concept, suitable for an authoritarian age’. Others have associated Utopia explicitly with totalitarianism.[21] Of the two, authoritarianism might be the more likely. There is a very clear desire in the setting out of the Utopian political and social system to have laws inculcated. The emphasis on what is referred to as ‘education’ or ‘training’ [institutis] might make 21st century readers think instead of socialisation or, more pessimistically, indoctrination. Priests, for example, are responsible for children’s education, and must ‘take the greatest pains from the very first to instil into children’s minds, while still tender and pliable, good opinions which are also useful for the preservation of the commonwealth.’[22] For this, not only are laws and institutions employed, but also public opinion. In a land where everything is public, nothing is private, and thus all is subject to public opinion: ‘being under the eyes of all, people are bound either to be performing the usual labor or to be enjoying their leisure in a fashion not without decency’.[23] This ‘universal behaviour’ is the secret to Utopia’s success. What I think More wanted to draw attention to in Utopia is the way in which this happens anyway, and to reorient the inculcation of values (or ‘opinions’) towards ‘truer’ or more ‘eternal’ (of course even ‘divine’) values. Utopians laugh at gems and precious metals because they associate them with fools and chamber pots. We value them because we associate them with the wealthy and powerful. The Utopians are ‘made’ to be dutiful citizens. As Book One suggests, ‘When you allow your youths to be badly brought up and their characters, even from early years, to become more and more corrupt, to be punished, of course, when, as grown-up men, they commit the crimes from boyhood they have shown every prospect of committing, what else, I ask, do you do but first create thieves and then become the very agents of their punishment?’.[24] In both cases, More suggests in Utopia and elsewhere, these values (or opinions) are built on a sort of ‘consensus’. The suggestion that this is authoritarian stems from a post-Enlightenment perspective that looks to see the liberal individual protected (as set out in part III above), of which More is many ways presenting a sort of ‘proto-critique’. While the republicanism of Utopia would, to some minds (and I would suspect to More’s), prevent it from being accurately labelled authoritarian—the citizenry is, after all, involved in its governance—to others this would not suffice. Would More have minded an ‘authoritarian’ society, if the values it inculcated with the ‘right’ ones? Perhaps not. More’s point, however, that we all submit to and are shaped by various sources of authority, and that the power to reorient the values cultivated by these authorities has been and continues to be a powerful one. Socialism/communism The early socialist thinkers were inspired by More to think that they might make people better through their organisation of society and its institutions (primarily education). In this historical context, we also have to contend, at least for a moment, with utilitarianism, and the Utopian’s ‘hedonism’ (or more properly Epicureanism). Jeremy Bentham, of course, held stock in the factory of utopian socialist Robert Owen. Helen Taylor (stepdaughter of J.S. Mill) wrote that in Utopia More ‘lays down a completely Utilitarian system of ethics’ as well as an ‘eloquently and yet closely reasoned defense of Socialism’. More was not an Epicurean (nor, of course, a utilitarian), though was interested to get back to more ‘real’ or ‘true’ pleasures over those false ones (we might think again of Utopians’ views of gems and precious metals). What I have called his republicanism might have also meant he was more interested in the good of the many over the few, though perhaps not quite in those terms (instead, the common good over any individual good). This emphasis on ‘common good’, of course, translates into ‘common goods’ in Utopia, where everything is held in common. This abolition of anything private (and thus private property) has led him to be read as a socialist and/or communist thinker, the latter not least by Marx and Engels. Beyond Utopia, however, More does make some very un-socialist comments. Through the central figure of Anthony in his Dialogue of Comfort (1534), More suggests in an Aristotelian vein that economic inequality is essential for the commonwealth; there must be ‘men of substance… for else more beggars shall you have’.[25] The golden hen must not be cut up for the few riches one might find inside. The larger point More wants to make in this text, however, is that even the richest do not ‘own’ their property. Property is a fiction and needs to be seen as such. Thus a rich man can keep his wealth so long as he recognises it is only his by the fictions of the society in which he lives, and ought (therefore) to be used to benefit the commonwealth. Wealth, position, and so on, More advocates, ‘by the good use thereof, to make them matter of our merit with God’s help in the life after.’ This is not a socialist nor a communist position, and it is certainly not materialist. More’s entire argument seeks to cultivate a conscious neglect of material realities in favour of the decidedly immaterial. Utopia, then, serves as a reminder of the immaterial realities underneath the social fictions generated in Europe (property, money, social hierarchy, etc). Living in that—shall we say—‘fictive reality’, however, means using those falsities towards the higher ends. As More’s friend John Colet put it: ‘use well temporal things. Desire eternal things.’ Utopianism Utopianism is at once an ideology, has characteristics similar to ideology, might encompass all ideologies, and is entirely opposed to it.[26] I will not rehearse the arguments of Sargent and Claeys here, but the three ‘faces’ that they speak of: utopian literature, utopian communities/practice, and utopian social theory are of course drawn from More’s 1516 text, and Sargent even suggests that ‘the meaning of [utopia] has not changed significantly from 1516 to the present’. So can we accept the obvious, then, that utopianism, as an ideology, is present in More’s text? Unfortunately, this question would seem to hinge on the fraught question of More’s sincerity in setting out the merits of the island of Utopia and the extent to which it is a community that he intended his readers to emulate. In many ways, our answer to this question has the power to overturn the very notion of any ideology being present in at least a surface reading of Utopia. If we were to conclude that Utopia is pure satire, and that the only arguments made in it are negative deconstructive ones, we would be hard-pressed to find any ideology within it at all.[27] I have made my own arguments about the central argument of Utopia, which I will not rehearse here, but the good news is that we can engage with the issue of utopianism in Utopia without answering this seemingly unanswerable question. Say what you will about the difficult question of More’s intentions, it would be difficult indeed to suggest that he was putting forward a blueprint of any kind for the construction of a practical community or endorsing the direct adoption of any of the practices exhibited in Utopia. The idea that Utopia exhibits—to use the words of Crane Brinton—‘a plan [that] must be developed and put into execution’ creates a sense of unease, to say the least. Afterall, More famously ends his text with the conclusion that ‘in the Utopian commonwealth there are very many features that in our own societies I would wish rather than expect to see’.[28] Despite the consensus that this passage is central to our understanding of Utopia, scholars have generally not attempted to read this statement in the context of More’s other works. When we do, we see that More applied this phrase elsewhere as well, and provided more of an explanation than he does in Utopia. In his Apology of 1533, More tells his reader that it would be wonderful if the world was filled with people who were ‘so good’ that there were no faults and no heresy needing punishment. Unfortunately, ‘this is more easy to wish, than likely to look for’.[29] Because of this reality, all one can do is ‘labour to make himself better’ and ‘charitably bear with others’ where he can. It is an internal reorganisation of priorities, drawn in large part from More’s reading of Augustine; what is common and shared must be prioritised over that which is one’s own. This, I have argued elsewhere, is what sits at the heart of More’s oeuvre, and we should be unsurprised to find it in Utopia as well. It is not the case, then, that More is advocating for what we might recognise as utopianism, but rather than Utopia is re-enforcing the arguments he makes elsewhere: the destructive power of pride and the personal need to prioritise the common over the individual. Conclusion: Moreanism? Does this mean, at last, we have come to an ideology in Utopia? A sort of republicanism-light, a proto-communitarianism, an anti-liberalism? I leave it to political theorists to hash out what More’s view might be termed—or indeed if a label is useful at all. Utopia can, indeed, be read in a variety of ways, which support a diversity of ideological positions. It becomes more difficult, I think, to read these positions into More’s thought as a whole. When we examine his corpus, we see a preoccupation with the common good, expressed through representative quasi-republican institutions, and the eternal/immaterial, but also a pragmatism (even ‘realism’?) about the artificialities of the world in which we live. It is the work of a much larger piece to flesh this out in whole, and this small article has instead focused largely on what More cannot be said to be. Hopefully, however, this is in itself a utopian exercise. In understanding Not-More, we might better understand More himself. [1] ‘Utopianism as a Political Ideology: An Attempt at Redefinition’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/04/utopianism-as-a-political-ideology-an-attempt-at-redefinition.html. [2] ‘“We Are Going to Have to Imagine Our Way out of This!”: Utopian Thinking and Acting in the Climate Emergency’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/09/we-are-going-to-have-to-imagine-our-way-out-of-this-utopian-thinking-and-acting-in-the-climate-emergency.html. [3] Adrian Blau, ‘Interpreting Texts’, in Methods in Analytical Political Theory, ed. Adrian Blau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 243–69, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316162576.013. [4] H. M. Höpfl, ‘Isms’, British Journal of Political Science 13, no. 1 (January 1983): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003112. [5] Thomas More, The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More: The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, ed. Louis A. Schuster, Richard C. Marius, and James P. Lusardi, vol. 8 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), 782. [6] Höpfl , ‘Isms’, 1; most of these do not appear in More’s work, though ‘papist’ does (24 times), which is a derivation of ‘papism’; likewise ‘donatists’ (26 times) from ‘donatism’ see https://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance/. Of course, this discussion is of English ‘isms’, and Utopia, along with a handful of More’s other writing, is Latin. Ism itself is a Latin (from Greek, and into French) derivation, for the suffix ‘-ismus’ (masculine). However, text-searches and concordances did not turn up many of these either, nor do ‘isms’ appear in the text of translations consulted. [7] ‘Concordances’, Thomas More Studies (blog), accessed 8 February 2022, http://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance-home/. [8] Quentin Skinner, ‘Thomas More’s Utopia and the Virtue of True Nobility’, in Visions of Politics: Volume 2: Renaissance Virtues (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 213–44. [9] Joanne Paul, Counsel and Command in Early Modern English Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), chapter 1. [10] More, Letters, 321. In the Confutation, 287 he justifies this approach, suggesting that ‘senatus Londinensis’ could be translated ‘as mayor, aldermen, and common council’. [11] More, Letters, 213. [12] More, Confutation, 146, 937. [13] Quentin Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), ix-x. This is not inconsistent with the fact that free-men could indeed become slaves in Utopia. In fact, the presence of slaves only highlights the emphasis on the sort of freedom enjoyed by law-abiding Utopian citizens.[13] Slaves are drawn from either within Utopia - those condemned of ‘some heinous offence’ - or without – captured prisoners of war, those who have been condemned to death in their own country or, thirdly, those who volunteer for it as a preferable option to poverty elsewhere.[13] Notably, in none of these cases is slavery hereditary and slaves cannot be purchased from abroad; Thomas More, More: Utopia, ed. George M. Logan and Robert M. Adams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 77. [14] More, Responsio Ad Lutherum, 277. All references to More’s works taken from the Yale Collected Works series, unless otherwise indicated. [15] Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty, 30-1. [16] Joanne Paul, Thomas More (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 98-9. [17] More, Utopia, 13. [18] Michael Freeden and Marc Stears, ‘Liberalism’, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [19] Paul, Thomas More, 99. [20] More, Responsio, 613. [21] Richard Marius, Thomas More: a biography (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 199), p. 235; Wolfgang E. H. Rudat, ‘Thomas More and Hythloday: Some Speculations on Utopia’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 43, no. 1 (1981): 123–27; J. C. Davis, Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Hanan Yoran, Between Utopia and Dystopia: Erasmus, Thomas More, and the Humanist Republic of Letters (Lexington Books, 2010), 13, 167, 174, 182-3. [22] More, Utopia, 229. [23] More, Utopia, 46. [24] More, Utopia, 71. [25] More, Dialogue of Comfort, 179. [26] Lyman Tower Sargent, ‘Ideology and Utopia’ in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [27] This leads me to address the Erasmus-shaped elephant in the room: what about humanism? Even if Utopia is entirely critical, then the ‘ism’ that might be left standing would be humanism. It’s important to note, however, that humanism has been rather unfortunately named, as scholars agree that it is most definitely not a defined or coherent system of beliefs, but rather a curriculum of learning, an approach to the study of texts and at most a series of questions to which ‘humanists’ provided a variety of answers. One of those question does indeed address the best state of the commonwealth, to which Utopia is a – thoroughly enigmatic – answer. [28] ‘in Utopiensium republica, quae in nostris civitatibus optarim verius, quam sperarim.’ [29] More, Apology, 166. 4/10/2021 Jean Grave, the First World War, and the memorialisation of anarchism: An interview with Constance Bantman, part 2Read Now by John-Erik Hansson

John-Erik Hansson: Let us now talk about the French and European contexts and turn to the First World War and to the relationship between anarchism and the French Third Republic. You discuss at length Jean Grave’s u-turn regarding the war and what leads him to draft and sign the Manifesto of the Sixteen, condemning him to oblivion, because he was one of the apostates—although other signatories like Kropotkin managed to remain in the good graces of a lot of people in the anarchist movement. There's an ongoing revision of our understanding of what exactly led to the split in the anarchist movement between the defencists, who were in favour of participating in the war, and those who simply opposed the First World War, exemplified by the recent edited collection Anarchism 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War.[1] For a long time being defencism was considered to be a betrayal of anarchist principles, but that view has changed over the last couple of years. What was Grave’s role in this debate? How does studying Grave help us rethink anarchism at that historical juncture?

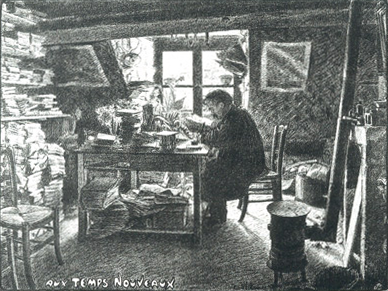

Constance Bantman: The first thing to say is that the revision is very much an academic thing; that’s important to highlight when you talk about anarchism, which is of course a social movement with a very strong historical culture. The war will come up when you're talking to the activists who really know their history when you mention Grave. On France’s leading anarchist radio channel, Radio Libertaire, a few years ago, I heard him called a “social traître” [traitor to the cause]—I couldn't believe it! But within academic circles, the revision is underway and a great deal has come out: the volume that you mentioned and Ruth Kinna’s work on Kropotkin as well, all of which have been very important to revising this history. That’s courageous work as well, given all we’ve said about the enduringly sensitive nature of this discussion. Concerning Grave’s role in this, the first aspect to consider is the importance of daily interactions in people's lives. That’s an angle you get from a biography. So much has been said about Kropotkin’s own story and intellectual positions, and how this informed his stance during the war. Of course, that doesn't explain everything, especially if you look to the opponents to the war. Grave was initially really opposed to the war, his transition was really gradual but it was a U-turn, connected to his friendship with Kropotkin, who told him off quite fiercely for being opposed to the war. One thing we do see through Grave is this sense that some anarchists clearly predicted what would later be known revanchisme, the idea that there was so much militarism in French society that when the Entente won the war, there would be really brutal terms imposed on Germany, which would lead to another war. That’s something that Peter Ryley has written about in Anarchism 1914-18. Some anarchists were pretty lucid actually in their analysis and you do found traces of that in Grave. He really clearly understood the depth of the militarism of French society, and that's when he did a bit of a U-turn. He was also in Britain at the time, and didn't quite realise how difficult the situation was. He had left Les Temps Nouveaux and the paper was looked after by colleagues. They were receiving lots of letters from the front, from soldiers and, as has been analysed by other historians, this was crucial in the growth of an anti-war sentiment for them. They could see directly the horrors happening in the trenches, whereas Grave was immersed in upper-class British circles and had no clear sense of the brutality of the war. So, again, it's a mixture of ideas, ideology, and the contingencies of personal and activist lives when you try to assess positions that such complicated times. JEH: Again, this highlights the importance of personal connections in the formulation of political and ideological positions. While these positions might be influenced by personal connections, they then become rationalised into arguments that become part of the ideological vocabulary and the ideological fault lines in the movement itself… and that leads to the Manifesto of the Sixteen, in a sense. CB: Yes, absolutely that's very true. The manifesto was written as a document published initially in the press; it was not a placard. Arguments in favour of defencism as well as arguments by anti-war groups were published in the press in the form of letters meant to influence people. Grave once referred to the Manifesto of the Sixteen as the manifesto he wrote in 1917, whereas it had actually been written in 1916. This just shows that what is now regarded as this landmark document, this watershed moment in the history of Western anarchism was, for Grave, just one of the many articles that he had written. I think it took some time, maybe a decade or two, you can see that through Grave, for the Manifesto to be consolidated into the historical monument that it now is. Looking at this period through Grave brings out a degree of fluidity which is otherwise not apparent. JEH: This is very interesting point. In a way, anarchists built their own historical narrative and created a landmark out of something that was, as you mentioned, initially just another set of arguments between people who are connected and often knew one another personally. But this particular argument became much more important because of the way in which the anarchist movement memorialised itself. CB: Yes, absolutely and I think tracing it would be interested to trace how national historiographies and activist memories sort of converge to establish versions of history. In France, I would be really interested to see when exactly the Manifesto of the Sixteen congealed into this historic landmark. I wonder if it's Maitron and a mixture of activist circles and discussions. I haven't studied so much the period around the Second World War, but really, with activist memories in this period we may have a missing link here to understand the formation and how the 19th century was memorialised. JEH: From the First World War to the Third Republic, I would like to relate your book to a recent article by Danny Evans.[2] Evans argues that anarchism could or should be seen as “the movement and imaginary that opposed the national integration of working classes”. Grave is interesting in this respect because he becomes domesticated by the Third Republic. Would you say that anarchism and French republicanism are in a kind of dialectical relationship from 1870 until the Second World War, moving from hard-hitting repression to the domestication of a certain strand of anarchism seen as respectable or acceptable by French republicanism? CB: Now that's a very good point, and an important contribution by Danny Evans. Grave always had these links with progressive Republican figures and organisations like the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, Freethinkers, academics etc.… One of his assets as well among his networks is his ability to get on with people, to mobilise them, for instance, in protest again repression in Spain and the Hispanic world. Many progressive figures were involved in that. And when Grave himself fell foul of the law during the highly repressive episode of 1892–94, many Republicans supported him, which suggests that a degree of republican integration was always latent for Grave. Then the war happened and he picked the right side from the Republicans’ perspective, and by then you're right, domestication is indeed a good term. I would also add that many of these Republicans considered that anarchism had been an important episode in the history of the young Third Republic, which might have made more favourably inclined towards it. Now if we look at domestication, Grave is an example of a sort of willing domestication, as you might say that perhaps he does age into conservative anarchism. But a classic example is that of Louise Michel. Sidonie Verhaeghe has just written a really interesting book about this[3], because if you think about Louise Michel having her entry into the Pantheon being discussed in recent years, she would be absolutely horrified at the suggestion. Having a square named after her at the foot of the Sacré Coeur, that’s almost trolling! But anarchism really reflects the history of the Third Republic from the early days, when the Republic was very unstable. You had the Boulangiste episode, and anarchism was perceived to be such a threat initially, until the strand represented by Grave ceases to be seen in that way. After the war, we enter the phase of memorialisation and reinterpretation; Michel and Grave represent two slightly different facets of that process. Regarding the point about the integration of the working classes, the flip side of Danny’s argument has often been used by historians—I'm thinking about Wayne Thorpe,[4] in particular—to explain why everything fell apart for French anarchists at the start of the First World War. The war just revealed how integrated the French working classes were, beyond the rhetoric of defiance they displayed. It's an argument you find to explain the lack of numerical strength of the CGT too. The working classes had integrated and the Republic had taken root, and Thorpe explains what happens with the First World War in the anarchist and syndicalist movements across Europe by looking at the prism of integration. That's a very fruitful way of looking at it. That's also great explanation because it encompasses so many different factors—economics, political control, and the rise of the big socialist parties which was of course crucial at the time. JEH: Actually, I was also thinking of the historical memory of socialists, as mass party socialism becomes dominant in the 20th century. In the late 19th century in the early 20th century when socialism was formulated, anarchism was an important part of that broad ideological conversation. But by the end of the First World War, from the socialists’ perspective, that debate is over. The socialists have won the ideological battle, and they are able to mobilise in a way that the anarchists aren't able to anymore. And at that point, the socialists can look back and try to bring anarchists into the fold, paying a form of respect to anarchism as an important part of socialist history. CB: Yes, I think there is probably an element of that, perhaps even an element of nostalgia. Many of these socialist leaders had dabbled with anarchism themselves before the war, so there is this dimension of personal experience and sometimes affinity. And it was still fairly recent history for them, I suppose, which plays out in a number of ways. There’s also the question of what happens with revolutionary ideas—for us the revolution is a fairly distant event, but for them the Commune was not such a distant memory. So, there is also this question of what do you do with a genuine revolutionary movement, like anarchism, and I think it was probably something they had to consider. [1] Ruth Kinna and Matthew S. Adams, eds., Anarchism, 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020); see also Matthew S. Adams, “Anarchism and the First World War,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, ed. Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_23. [2] https://abcwithdannyandjim.substack.com/p/anarchism-as-non-integration [3] Sidonie Verhaeghe, Vive Louise Michel! Célébrité et postérité d’une figure anarchiste (Vulaines sur Seine: Editions du Croquant, 2021). [4] Wayne Thorpe, “The European Syndicalists and the War, 1914-1918”, Contemporary European History 10(1) (2001), 1–24; J.-J. Becker and A. Kriegel, 1914: La Guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français (Paris: Armand Colin, 1964). 27/9/2021 Jean Grave, print culture, and the networks of anarchist transnationalism: An interview with Constance BantmanRead Now by John-Erik Hansson

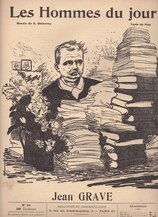

John-Erik Hansson: Let's start with a few introductory questions. Very broadly, who Jean Grave and why should we study him? What does he stand for? Does the book present a general case for studying minor figures in the history of anarchism, as Jean Grave is no longer necessarily so well known?