by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

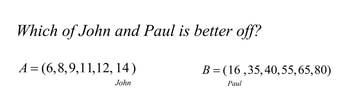

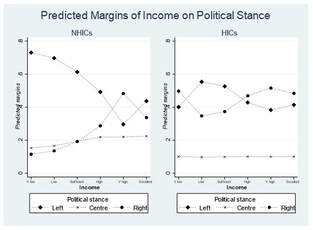

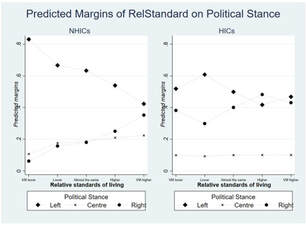

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

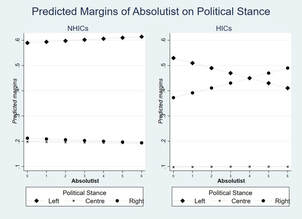

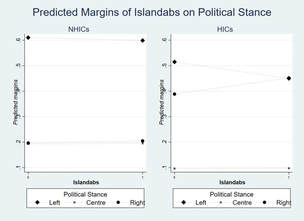

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. 25/4/2022 Revisiting the original Palaeolithic democracies to rethink the postliberal democracies of the futureRead Now by F. Xavier Ruiz Collantes

Why do we overlook the original democracies?

God created the world six thousand years ago. Human beings are not related to primates. There is no such thing as climate change. The first democracy emerged in classical Athens. There are some important groups that continue to hold fast to certain beliefs, despite the availability of a mass of contrary evidence. One such group is composed of many people interested in history, philosophy and political theories. While there is ample evidence that democratic principles were applied to power relations in Palaeolithic Homo sapiens communities tens of thousands of years, i.e., long before the Athenian democracy of antiquity emerged, a mainstream claim in history, philosophy and political theory discourses continues to be that democracy first emerged in Athens. It has been documented, in the political anthropology and evolutionary anthropology fields, that the first political systems—those that have governed us for most of our existence on this planet—were democratic. The existence of these democracies, which I call the “original democracies”, is confirmed by two types of evidence. Firstly, in different parts of the world, hunter-gatherer communities that have survived in a form close to their original Palaeolithic form, organise themselves politically according to democratic principles, e.g., African peoples such as the Bushmen and Pygmies, Australian and New Guinean Aborigines, indigenous Amerindian peoples, etc. Secondly, Palaeolithic fossil records provide evidence of egalitarian and non-hierarchical societies. Considering just the Upper Palaeolithic,[1] democratic hunter-gatherer communities lasted several tens of thousands of years; in contrast, non-democratic, authoritarian systems only began to emerge less than ten thousand years ago, during the Neolithic,[2] with the consolidation of agriculture and livestock herding and a sedentary way of life. The fact that many historians, philosophers and political theorists hold that democracy first emerged in classical Athens is certainly problematic, yet it is also very significant, because it reflects perceptions of our species derived from the epistemological bias of Western and contemporary culture, determined by extreme chrono-centric and ethno-centric perspectives that run very deep. Ultimately, such perspectives contribute to placing the contemporary white race originating in Western culture at the top of the evolutionary tree and legitimises its usurpation of the planet. Numerous authors, however, when they write about democracy, also refer to Palaeolithic democracies, e.g., Federico Traversa, Kenneth Bollen, Pamela Paxton, Doron Shultziner and Ronald Glassman. [3] Those democracies of the Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer peoples are called “Palaeolithic democracies” by Doron Shultziner, “community democracies” by Federico Traversa and “campfire democracies” and “clan and tribal democracies” by Ronald Glassman. I suggest that these democracies should preferably be called "original democracies”, first, because this term better reflects the importance of these democracies in the evolution of humanity, and second, because it establishes a chronological sequence going back in time, from modern democracies to ancient democracies to the original democracies. The evolution to Homo sapiens: a journey towards democracy Palaeolithic democracies, which emerged in all parts of the world settled by Homo sapiens, undoubtedly represent the most important cultural development of our species, first, because these democracies reflect almost all of human existence, and second, and more importantly, because these democracies have greatly shaped the natural and cultural tendencies of Homo sapiens. Joseph Carroll [4] identifies four different power systems, reflecting periods from the emergence of hominids to the Homo sapiens of today: (1) alpha male domination; (2) Palaeolithic egalitarian and democratic systems; (3) despotic or authoritarian domination as emerged with the Neolithic; and (4) Western Modernity systems deriving from democratic revolutions. Homo species split from the pan species about six million years ago [5]. This evolutionary divergence reflected a journey to democratic communities from the alpha male-dominated despotic communities, typical, for instance, of current great apes species such as chimpanzees and gorillas. The evolutionary journey to Homo sapiens is, therefore, also a journey from despotism to Palaeolithic democracy. Broadly speaking, what we understand by a democratic system for organising and equally distributing political power within a community is specific to Homo sapiens. Various factors led to the disappearance of the alpha male in Homo sapiens hunter-gatherer communities. The advent of lethal weapons meant that subjugated individuals could easily kill an alpha male; the need for cooperation in hunting and raising children generated a communitarian and egalitarian spirit; and the development of hypercognition and language meant that decision-making affecting a community could be based on open and joint deliberation by members. The tens of thousands of years in which humans lived in Palaeolithic democratic communities has left deep marks on our species. These include the development of discursive capacities that enabled deliberation, negotiation and cooperation and also the burgeoning of a certain morality based on the principles of justice and equity. This morality, original, egalitarian and democratic originated in the Upper Palaeolithic, explains why present-day humans are largely repulsed by abusive coercion, non-legitimate power and arbitrary decisions deemed unjust. While humans have inherited (from the hominin species prior to Homo sapiens) a tendency to dominate others, they have also developed al sense of egalitarianism and anti-domination. Our social morality and politics operate within this contradiction. For all these reasons, while we have a tendency towards domination over others, we also tend to reject domination over ourselves and others. The sense of democratic and egalitarian morality that beats in the heart of humans is largely due to the evolutionary development of Homo sapiens living in democratic and egalitarian hunter-gatherer communities of the Palaeolithic. Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer communities, and later tribal societies, did not have a state, as this form of governance developed later from primitive chiefdoms and kingdoms. But the fact that there was no state did not mean that there were no politics and no social power systems. Circumscribing politics exclusively to societies with a state reflects chrono-centric bias. The original Homo sapiens communities clearly demonstrate that politics reached beyond the historical existence of the state. The main problem in considering hunter-gatherer communities to be fully democratic is that, in those peoples that survive to this day, the most important decisions are generally made by adult males. While the exclusion of women would suggest a significant democratic deficit, it is no greater a deficit than that of classical Athens or even, until universal suffrage for men and women was finally introduced, of that of our liberal democratic societies. Nonetheless, this issue has given rise to controversy, as important archaeologists and anthropologists, such as Lerna Lerner, Riane Eisler, and Marilène Patou-Mathis, [6] argue that women during the Palaeolithic had the same prestige and power as men and that this status was not lost until the Neolithic. As evidence, they indicate that the archaeological record does not unequivocally demonstrate that men had a superior status to women, and they further argue that the notion that Palaeolithic women were subordinate is simply a product of the andro-centrism that overwhelmingly dominated early archaeology and anthropology work. If women did indeed possess the same status as men, then those communities were truly democratic. There is a fundamental problem in studying Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer communities from similar communities that have survived to the present day, namely, that, in recent centuries, many of the surviving communities have seen their original way of life contaminated, degraded or radically suppressed by other cultures and by domination exercised by other cultures, especially modern and Western empires. This is an accelerating process and, as time passes, it becomes increasingly difficult to obtain reliable data on the original political life of hunter-gatherer and tribal peoples. The domination and influence of states, empires and large business corporations, aided by the new technologies, today reach into all corners of the earth. The consequences for the original hunter-gatherer peoples is that they no longer preserve their original forms of life and culture. Democratic systems in Palaeolithic communities Democratic systems and decision-making bodies existed in both hunter-gatherer and mobile tribes, according to anthropological studies, which document organs of power such as community assemblies, functional leadership and community chiefs. Space does not allow for an extensive explanation of the political organisation of hunter-gatherer communities. However, some brief considerations are necessary, because despite being limited and even reductionist, they can also be very illustrative. Although the records that throw light on these early political power systems are drawn from peoples who have lived within their original systems until recently, in what follows the past tense will be used because those communities are assumed to have existed during the Upper Palaeolithic. We can, for instance, point to the existence of “community assemblies”, which were meetings of all adults to discuss, deliberate and reach agreements on fundamental issues affecting their community’s future. All adult members of the community, men and women, participated in these assemblies, although, from some of the known present-day communities of hunter-gatherers and horticulturists, we can deduce that smaller and more formal assemblies were composed only of adult males. In many cases, the women stood around those smaller assemblies, actively participating and making their voices heard. In hunter-gatherer community meetings, decisions had to be made by consensus, as the survival of small communities depended on cooperation between members. The search for consensus often meant that the assemblies were extremely lengthy, while no decisions were even reached if there was no unanimity. Community fusion and fission processes were common in hunter-gatherer communities, and, in cases of great conflict, the solution was for the community to split. Persons who excelled in public speaking skills and persuasive strategies were important and acquired prestige in community assemblies. Kenneth E. Read, [7] in an article describing the political power system of the Gahuku-gama (an aboriginal people of New Guinea), provides an excellent explanation of individual communication strategies aimed at influencing community assemblies. In some hunter-gatherer peoples a group strategy that ensured that no one would try to put themselves above the rest was ridicule and laughter directed at people who used bombastic oratory to impress. We can also distinguish individuals who could be defined as "functional leaders" or "task managers”, i.e., men or women who were expert or skilled at a particular task, e.g., hunting, warfare, healing, birthing, music, dance, various rituals, etc. Leadership was not a designated role; rather, roles were acquired by individuals who demonstrated particular knowledge, experience or skills. Leaders only had the authority as permitted by the community and only for the performance of their assigned tasks. Although they held the most important political position in hunter-gatherer communities, chiefs were typically powerless. That is why they were a major source of surprise for the first Europeans who came into contact with these communities. Roberth H Lowie, who studied the chiefs of Amerindian peoples, such as the Ojibwa, the Dakota, the Nambikuara, the Barana, etc, concluded that chiefs did not have any coercive force to impose their decisions, nor had they executive, legislative, or judicial power. They were fundamentally peacemakers, benefactors and the conduit of community principles and norms. Fundamentally, they functioned as mediators and peacemakers in internal conflicts and resource providers to community members in need, and also provided periodic reminders of the norms and values on which member coexistence and community survival depended. [8] This figure of the powerless chief has been encountered in hunter-gatherer communities around the world. According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, the benefits of being a community chief were so few and the burden of responsibility so high that many refused to assume the role. However, what did motivate some individuals to assume the chiefdom was the associated prestige and a vocation to assume certain responsibilities for the community. [9] The community chief was generally elected by the adult community members—men and women—and could also be removed by the community. An example is given by Claude Levi-Strauss in his explanation of the power system of the Nambikwara in Brazil: if the chief was egoistic, inefficient or coercive, the community dismissed or abandoned him. [10] In some tribes, while war chiefs acquired important executive powers, these could only be exercised in periods of war, and despite the associated prestige, they had few or no powers in peacetime. It can hardly be argued that these hunter-gatherer communities—the original democracies—were not democratic, as argued by some authors. Karl Popper, for instance, stated that they were not "open societies" and were therefore undemocratic. [11] However, this argument is based on a liberal perspective: Popper essentially claimed that they were not liberal societies. Yet those societies were profoundly communitarian and egalitarian and, although they were not what we currently understand as liberal, they were in their way democratic. Political theory and political anthropology In the field of modern Western political theories, the tendency to overlook the relevance of the original democracies in the history of humanity is the outcome of the narrow perspective of our cultural tradition. What we call modern democracies are little more than two hundred years old, yet for some thirty thousand years, the original democracies organised the political power structures of Homo sapiens, with the resulting decisive impact on our evolution and on what we are today. Instead of taking into account the reality of the original democracies, Western thinking has focused on establishing hypotheses—with little foundation in reality—regarding illusory states of nature and assumed contracts between individuals aimed at shaping a society and, further on in time, creating a state. Thus, instead of taking into account the key contributions of anthropology, Western thinkers have explored the contractarian ideas of authors like Hobbes, Rousseau, Locke, and Kant, not to mention other more recent authors inspired by liberal contractualism, e.g., Rawls and Nozick. Human society and its political power systems did not originate from a contract between isolated individuals, but from the evolution of societies and power systems of other Homo species from which Homo sapiens arose. Given that the evolutionary processes that gave rise to the first human societies are known, the contractarian origin myth—a device that legitimises liberal individualism—makes little sense, even as a mere logical hypothesis for reflection. In their introduction to a classic overview of the political systems of African peoples, the anthropologists Meyer Fortes and Edward Evans-Pritchard argued that the teachings of political philosophy were of little help with ethnographic research into the political systems of African peoples as conducted by anthropologists in the field. [12] The philosophy, political and anthropological disciplines may be very different, but both philosophers and political theorists need to take anthropological data into account in their reflections. Political principles of the original democracies Two anthropologists in particular, in their reflections on the political systems of hunter-gatherer peoples, have developed important theoretical models: the French anthropologist Pierre Clastres and the US anthropologist Christopher Boehm. Pierre Clastres, whose thinking has strongly influenced French theorists such as Claude Lefort and Miguel Abensour, drew a novel conclusion from his ethnographic studies of Amerindian peoples in the Amazon region in the 1970s, namely, that hunter-gatherer peoples were not people without a state. Rather, they acted against the state, i.e., their political power systems were designed so that no state would ever emerge. For this reason, communities always tried to ensure that their chief was a chief with little or no power, while the community as a whole and its assembly was considered to predominate over any other political power that might be established. [13] As for Christopher Boehm, he concluded, from a detailed study of a large number of ethnographic works conducted in almost all continents, that the political systems of hunter-gatherer peoples were based on the principle of a reverse dominance hierarchy, in which the communities established formal and informal systems that ensured that a chief never achieved power, that no political body could coerce the community, and that no individual or group could prevent community members from freely making decisions on matters that concerned the community. Systems of control over the power of chiefs or leaders ranged from mild punishments, such as ridicule, to much more serious punishments, such as ostracism, banishment or even execution. For Christopher Boehm, the first genuinely human taboo was the taboo of dominance, and the first individual outlawed by the Homo sapiens community was the individual with aspirations to be the alpha male of the community. [14] Both principles—Clastres’ society against the state and Boehm’s reverse dominance hierarchy—are valid, but neither has been applied to date to develop theories consistent with models of democracy. Of the two principles, I consider the reverse dominance hierarchy to be the more productive principle, among other reasons, because it allows us to think about forms of non-state domination of a community. If, for instance, we transfer this principle to modern societies, it would apply to the dominance of certain groups in our society, not only in relation to the control of state apparatuses, but also to the wealthy, religious leaders, private armed militias, excessively powerful corporations, and media and information and communication systems oligopolies, etc. From my point of view, the reverse dominance hierarchy leads to a model of democracy that separates domination from management. In the original democracies, chiefs could exercise direction and influence but held little or no power; rather, it was the community as a whole, through its deliberative assemblies and other formal and informal decision-making mechanisms, which held power over itself, including over the chief, and also over alpha males aspiring to take power, who would be banned by the community. The reverse dominance hierarchy in original democracies allowed communities to freely take decisions over themselves without the interference and dominance of individuals and powerful groups. Adapting this principle to modern societies would lead to reflection on alternative models of democracy. Why revisit the original democracies? My focus on the original democracies is not intended as an exercise in historical or anthropological scholarship, but is grounded in two needs. First, we need to respect the remaining indigenous and aboriginal communities on our planet, as an enormous reserve of democratic culture, ancestral wisdom and human dignity. In recent centuries, their numbers have been greatly reduced, their communities have been annihilated, and their members have been enslaved and acculturated by Western imperialism and predatory capitalism. Second, we need to revisit the moral and political principles of the original democracies in order to be able to rethink our own democracies and our democratic projects for the future. For instance, I consider the reverse dominance hierarchy principle to be a very fruitful and interesting concept for rethinking the notion of democracy. I also believe that we could reflect on the notion of “people” in accordance with political characteristics of hunter-gatherer communities in defence of freedom and the power of the community as a whole. Liberal democracy, the hegemonic form of democracy today, is clearly in crisis, among other reasons due to its increasingly diminished legitimacy in society. The fact that liberal democracy allows socioeconomic inequalities to grow to a disproportionate degree leads to the suspicion that elected politicians do not really represent the majority of voters, thereby reflecting a profound crisis of representation. Moreover, the alliance between liberal democracy and runaway capitalism and its fostering of senseless consumerism and unbounded economic growth is leading scientists and conscientious citizens to fear the planet and humanity are headed for ecological collapse. An important task for political theorists today is to consider alternative forms of post-liberal democracy that lead to greater equality and freedom. Democracy, in sum, needs to be rethought. While republicanism, since the end of the last century, has developed a line of thinking that seeks to renew democracy by drawing on sources such as classical Greece, the Roman Republic and the Italian republics of the Renaissance, those sources are too close to our own culture; they are, in fact, where our political culture originated. We need, surely, to decentralise more, to seek inspiration in sources more remote from our habitual way of thinking—because, if our thinking is derived from what is familiar, then we will likely continue to think in the same way and devise broadly similar solutions. Rethinking democracy by considering Palaeolithic communities has a number of advantages. Looking back to those cultures so foreign to us could bring us closer to alternative perceptions of the human power relationships, and so opens up perspectives lost to us. Furthermore, those different perceptions would not be fanciful or speculative but anchored in reality, and would reflect deeper and more specific aspects of our nature as a species. Palaeolithic cultures can show us that another way of being human and of being a community is possible because that alternative form of humanity lies in our own evolutionary roots. It is not about appealing for the return to an idealised past, as this is evidently neither possible nor desirable, given the immense differences between the original democracies and modern urban and technologically advanced societies. Rather than some kind of futile anachronistic exercise, it is a matter of seeking new references that break with known modes of thinking. It is about looking forward, but considering what led to our present. And what led to our present is not only a few millennia of human authoritarianism and despotism, but also tens of millennia of egalitarian and democratic communities. Hunter-gatherer peoples may not have a written culture, but they do have a very rich oral culture—even if it is increasingly impoverished by the intrusion of Western culture. The myths that they keep alive are their means for formulating deep political thought; those myths also reveal their way of life and their governance and political systems. Undoubtedly we have much to learn from these original democracies, and much to reflect on and to rethink regarding their practices and the data and reflections of the anthropologists who have studied them. [1] The Upper Palaeolithic dates to approximately 40,000 to 10,000 years ago. [2] The Neolithic dates to approximately 10,000 to 5,000 years ago. [3] See: Glassman, R. M. (2017). The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States. Springer; Bollen, K. & Paxton, P. 1997. Democracy before Athens. Inequality, democracy, and economic development 13-44. Cambridge University Press; Traversa, F. (2011). La gran transformación de la democracia: de las comunidades primitivas a la sociedad capitalista. Ediciones Universitarias; Shultziner, D. (2007). From the Beginning of History: Paleolithic Democracy, the Emergence of Hierarchy, and the Resurgence of Political Egalitarianism Shultziner et al. (2010). The causes and scope of political egalitarianism during the Last Glacial: A multi-disciplinary perspective. Biology & Philosophy, 25(3), 319-346. [4] Carroll, J. (2015). Evolutionary social theory: The current state of knowledge. Style, 49(4), 512-541. [5] Pan species that have survived to this day are the chimpanzee and the bonobo. They are part of the family of the great apes (hominids), which includes humans, gorillas and orangutans. [6] See: Eisler, R. (1987). The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future. Harper Collins; Lerner, G. (1990). La creación del patriarcado. Editorial Crítica; Conway Hall; Patou-Mathis, M. (2020) L’homme préhistorique est aussi une femme. Allary. [7 Read, K. E. (1959). Leadership and consensus in a New Guinea society. American Anthropologist, 61(3), 425-436. [8] Lowie, R. H. (1948). Some aspects of political organization among the American aborigines. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 78(1/2), 11-24. [9 ] Lévi-Strauss, C. (1967).The social and psychological aspects of leadership in a primitive tribe, in Cohen and Middleton, Comparative Political Systems. New York: Natural Historical Press. [10] Lévi-Strauss, C. (1992). Tristes tropiques. Penguin Books. [11] Popper, K. (1966) The Open Society and its Enemies. Routledge & Kegan Paul. [12] Fortes, M., & Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (2015). African political systems. Routledge. [13] See: Clastres, P. (1974). La société contre l'Etat. Minuit; Clastres, P. (1977). Archéologie de la violence: la guerre dans les sociétés primitives. Editions de l'Aube. [14] See: Boehm, C. (2012). Ancestral hierarchy and conflict. Science, 336(6083), 844-847; Boehm, C. (2000). Conflict and the evolution of social control. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(1-2), 79-101; Boehm, C. (1999). Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior. Harvard University Press. by Federico Tarragoni

In an old textbook on populism, the psycho-sociologist Alexandre Dorna described the phenomenon as a 'volcanic eruption': a surge of the repressed impulses, instincts and fantasies of the masses onto the political scene.[1] This analysis is very common today, especially in relation to the so-called 'far-right populisms', such as the governments of Trump, Bolsonaro, or Orbán. We will not be talking here about the fantasies (in a Freudian sense) of which populism would be the political vector, but about those that it expresses in the speaker who speaks about it. What exactly are we saying when we categorise something as 'populist'? It is well known that the word is used more to stigmatise than to designate positively. Its proliferation in public debate over the past decade has been unprecedented: in 2017 the Cambridge Dictionary awarded it 'word of the year'. Its inflation in the public debate points to the undeniable re-emergence of the ‘people’ as political operator, especially since the subprime crisis of 2008. On the extreme right, this resurgence is expressed in xenophobic nativist movements that oppose the national people to immigration and to ethnic and sexual minorities. On the far left, it appears in plebeian movements that oppose the ‘people’ as a democratic subject to a ruling class, judged to be in collusion with neoliberal economic elites, and accused of corrupting democracy. Both renewals emerge in the global political space. While the former may be compatible with a neoliberal economic orientation, as in the cases of Trump and Bolsonaro, the latter is in frontal opposition.