by Iain MacKenzie

Twenty years ago, the lines of debate between different versions of critically-oriented social and political theory were a tangled mess of misunderstandings and obfuscations. The critics of historicist metanarratives were often merged under the banner of postmodernism, grouped together in (sometimes surprising) couplings—postmodernism and poststructuralism, poststructuralism and post-Marxism, deconstruction and postmodernism—or strung together in a lazy list of these terms (and others) that usually ended with the customary ‘etc.’. Although this was partly the result of ‘posties’ still figuring out the detail of their respective challenges to and positions within modern critical thought, it was also a way of finding shelter together in a not altogether welcoming intellectual environment.

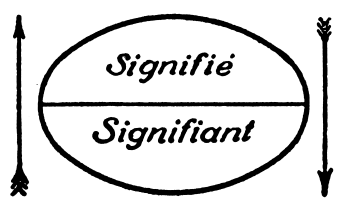

This is because it was not only the proponents of various post-isms who were unsure of what they were defending, it was also that the critics of these post-isms were indiscriminately attacking all the post-isms as one. They would cast their critical responses far and wide seeking to catch all in the nets of performative contradiction, cryptonormativism and quietism. ‘Unravelling the knots’ proposed one way of clarifying one post-ism—poststructuralism—as a small step toward inviting other posties to clarify their own position and critics to take care to avoid bycatch as they trawled the political seas.[1] That was twenty years ago: has anything changed? In many respects, yes; but not always for the better. Within the academy, taking course and module content as a rough indicator, poststructuralism has become domesticated. Once a wild and unruly animal within the house of ideas, it is now a rascally but beloved pet that we all know how to handle.[2] In political studies, this domestication has come in two ways.[3] First, it has become customary to acknowledge one’s embeddedness within regimes of power/knowledge, such that almost everyone of a critical orientation is (apparently) a Foucauldian now. Second, it has become commonplace to study discourses and how they shape identities, adding this to the methodological repertoire of political science. These two simple gestures often merit the titular rubric ‘A Poststructuralist Approach’ and yet they often remain undertheorised in the manner discussed in the original article. Often, there is neither a fully-fledged account of the emergence of structures nor an account of how meaning is constituted through the relations of difference that define linguistic and other structures. Without such in-depth accounts, we are left with empirically rich but ultimately descriptive accounts of how social forces impinge on meaning, which can have its place, or the treatment of language as a data source to be mined in search of attractive word clouds (or equivalents), which can also have its place. Whatever these claims and methods produce, however, it is not helpful to call them ‘poststructuralist’. There is still a need for the exclusive but non-deadening definition of this term, so that it is not confused with the tame house pet with which it is associated today. Part of the problem is that the discussion of how structures of meaning emerge and how they function through processes of differentiation before any dynamics of identification requires, let’s say in a Foucauldian tone, the hard work of genealogy: the patient, gray and meticulous work of the archivist combined with the lively critical work of the engaged activist.[4] But, these days, who has the patience, and the energy, for genealogy? And, in many respects, the difficulties associated with constructing intricate ‘histories of the present’ have led to a tendency to short-circuit the genealogical process (and other poststructuralist methods[5]) under the name of ‘social constructivism’. It is a shorthand, however, that has generated new entanglements, new knots, that have come to define what those of us with a long enough memory can only regret are now frequently labelled the culture wars. On one side, there are the alleged heirs of the posties, awake to the constructed nature of everything and the subtleties of all forms of oppression. On the other side, there are the new defenders of Enlightenment maturity striving to protect science from constructivism and to guard free-speech from the ‘cultural Marxists’. This epithet, of course, is the surest sign that we are in a phoney war—albeit one with real casualties—as it mimics the trawling habits of previous critics but industrialises them on a massive scale. Claims about the deleterious effects of ‘cultural Marxists’ and their social constructivist premisses simply scrape the seabed and leave it barren. But much like the debate twenty years ago, those seeking to defend ‘social constructivism’ cannot swim out of the way unless they specify that this, and other phrases like it, should never be used to end an argument. There is no use in proclaiming a social constructivism if, after all, the social itself is constructed. Shorthand is always helpful but only if we know that it is exactly that and that it will always need careful exposition and explication when critics raise the call. Moreover, what is often forgotten, in the heat of battle, is that the task is not simply to clarify one’s own claims in response to critics but to reflect upon the nature of critical exchange itself. One side of the culture wars take lively spirited debate as the signal of a flourishing marketplace of ideas. Those on the side of social construction appear to agree, simply wanting it to be a regulated marketplace of ideas. What poststructuralism brings to market is succour for neither side. Forms of critical engagement bereft of analyses of the current structures of socially mediated critical practice will always fall short of the poststructuralist project and typically dissolve into the impoverished forms of communicative exchange that never rise above the to-and-fro of opinion. It is incumbent, therefore, on poststructuralists to have a view on the nature of public interaction through social media and how these interlock with different forms of algorithmic governmentality.[6] In this way, the social constructivist shorthand can be given real critical purchase by delving deeply into the nature of public discourse and the technological forms that sustain it, particularly because these make state intervention in the name of ‘the public’ increasingly difficult (even though they can also be used, to a certain extent, for statist purposes). That said, the culture wars obfuscate a deeper misunderstanding about poststructuralism. To grasp this, however, it is important to be reminded of the overarching project of poststructuralism: it is a project aimed at completing the structuralist critique of humanism. It is important to specify this a little further. Humanism can be understood as the project of bringing meaning ‘down to earth’ so that it is in human rather than divine hands. Given this, we can articulate structuralism in a particular way: it was a series of responses to the ways in which humanism tended to treat the human being as a surreptitiously God-like entity and source of all meaning. Structuralism was the project aimed at completing the founding gesture of humanism. Poststructuralism simply recognises that there are tendencies within structuralism that similarly treat structures as analogous to God-like entities that serve as the basis of all meaning. In this respect, poststructuralism is the attempt to complete the project of structuralism, which was itself aimed at completing the project of humanism. When we understand poststructuralism in this manner it is an approach to thinking (and doing) that seeks to remove the last vestiges of enchanted, supernatural, forces, entities and explanations from all theoretical and practical activity, including science but also philosophy and the arts (broadly understood). Given this, there is no room for a pseudo-divine notion of the social that often haunts ‘social constructivism’. Indeed, given this articulation of its project, poststructuralism is hardly anti-science (as some in the culture wars might claim); rather, it is a project of understanding meaning in every respect without reinstating a source of meaning that stands ‘outside’ or ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the world that we inhabit. In fact, poststructuralists (though not all posties) are rather fond of science and they certainly do not want to undermine the natural sciences in the name of lazy ‘social constructivism’. It is, in fact, a way of seeking better science with help of philosophy, and a way of seeking better philosophy with the help of science (and for the full sense of what’s at stake, this gesture should be triangulated through inclusion of the arts). But how can there be a ‘better’ if the posties, including the poststructuralists, are sceptical of metanarratives? This question brings us to one of the more fruitful aspects that has changed in the last twenty years. The most interesting challenge faced by poststructuralists in recent times has come from the emergence of forms of neo-rationalism looking to reinvigorate critical philosophy through pragmatically oriented forms of Kantianism and non-totalising forms of Hegelianism.[7] From the neo-rationalist perspective, poststructuralism has failed in its attempts to naturalise meaning, to take it away from explanations that rely upon supernatural forces, to the extent that it is reliant upon a transcendent notion of Life that treats the priority of becoming over being as given. This immanent critique of poststructuralism cuts much closer to the bone than the Critical Theory inspired fishing which cast their nets wide but always from the harbour of their own shores. At the heart of this dispute is whether or not what we know about the world and how we know what we know about the world can be articulated within a single theoretical framework. For the neo-rationalist, it is (in principle, at least) possible to work on the assumption that there is an underlying unity between ontology and epistemology founded upon a specific conception of reason-giving. For poststructuralists, exploration of the conditions of experience suggests a dynamic distance between the what and the how, such that the task is to secure the claims of philosophy, art and science as equal routes into our understanding of both. While this reconstitutes a certain return to the pre-critical debates between rationalists and empiricists, it is equally indebted to the critical turn with respect to the shared task of legitimating knowledge claims, but with a pragmatic or practical twist. Both the neo-rationalists and the poststructuralists pragmatically assess the worth of the knowledge produced by virtue of the challenges they proffer to arguments that rely upon a transcendent God-like entity and the dominant form of this today; namely, the sense of self-identity that underpins capitalist endeavours to maximise profit. This critical perspective, perhaps surprisingly, was seeded within the fertile soil of American pragmatism. For the pragmatists—and we might think especially of Pierce, Sellars, and Dewey—it is the practical application of philosophy that engenders standards of truth, rightness and value. Admittedly, in the hands of its founding fathers, this practical application was often guided by the idea of maintaining the status quo. But that is not essential. Neo-rationalists and poststructuralists have found a shared concern with the idea that philosophical practice should be guided by the critique of capitalist forms of thought and life. As such, they share a common ground upon which meaningful discussion can be forged, aside from the culture wars (which are simply a reflex of capitalist identitarian thinking). While deep-seated divisions remain—does the knowledge generated by social practices of reason giving trump the experience of creative learning or are they on the same cognitive footing?—the shared sense of seeking a critical but non-final standard for what counts as better (better than the identity-oriented thinking sustaining capitalism) is driving much of the most productive debate and discussion at the present time. Work of this kind reminds us that poststructuralism is still a wild animal rather than a domesticated house pet, that it is a critical project but also one that has political intent. That said, it is not always easy to convey the political dimension of poststructuralism, especially given the vexed question of its relationship to ideology. As discussed in the original article, part of the initial excitement about poststructuralism was that its major figures distanced themselves from the idea of ideology critique. However, this was only ever the beginning of a complex story about the relationship of poststructuralism to ideology and never the end.[8] While Marxist notions of ideology were critiqued for the ways in which they incorporated notions of the transcendental subject, naïve versions of what counts as real and over-inflated notions of truth, poststructuralists have always endorsed the power of individual subjects to express complex notions of reality and historically sensitive and effective notions of truth, and to do so against dominant social and political formations. These formations are often given unusual names—dispositif, assemblages, discourses, and such like—but the aim of unsettling and ultimately unseating the dogmatic images and frozen practices of social and political life is not too distant from that animating Marxism. Of course, as Deleuze and Guattari expressed it, any revised Marxism needs to be informed by significant doses of Nietzscheanism and Freudianism (just as these need large doses of Marxism if they are to avoid becoming critically quietest and practically relevant for the critique of capitalism).[9] What results, though, is an immanent version of ideology critique rather than a rejection of it tout court: there are many assemblages/ideologies that dominate our thoughts, feelings and behaviour and it is possible to learn how they operate by making a difference to how they function and reproduce themselves. In searching for the natural bases of meaningful worlds it is no surprise that poststructuralists have become adept at diagnoses of how natural processes can lead to systems of meaning that import supernatural fetishes into our everyday lives, and how these are sustained in ways even beyond merely serving the interests of the economically powerful. There appear to be an endless number of these knots that need untying. If we want to untie at least some of them, then unravelling the knots that currently have poststructuralism tangled up in a phoney culture war is another small step on the road to bringing a meaningful life fully down to earth. [1] I.MacKenzie, ‘Unravelling the knots: post-structuralism and other “post-isms”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 6 (3), 2001, pp. 331–45. [2] I. MacKenzie and R. Porter, ‘Drama out of a crisis? Poststructuralism and the Politics of Everyday Life’, Political Studies Review, 15 (4), 2017, pp. 528–38. [3] One of the interesting features of the recent history of poststructuralism is that it is not the same across disciplines. Of course, this need for disciplinary specificity with respect to how knowledge is disrupted, new forms of knowledge established and then domesticated is part of what poststructuralism offers. That said, much of what follows can be read across various disciplines in the arts, humanities, sciences and social sciences to the extent that the legacies of humanism and historicism traverse these disciplines. [4] M. Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in D. Bouchard (ed.) Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault (New York: Cornell University Press, 1992 [1971]), pp. 139–64. [5] B. Dillet, I. MacKenzie and R. Porter (eds) The Edinburgh Companion to Poststructuralism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013). [6] A. Rouvroy, ‘The End(s) of Critique: data-behaviourism vs due-process’ in M. Hildebrandt and E. De Vries (eds), Privacy, Due Process and the Computational Turn. Philosophers of Law Meet Philosophers of Technology (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 143–68. [7] See R. Brassier’s engagment with the work of Wilfrid Sellars, for example: 'Nominalism, Naturalism, and Materialism: Sellars' Critical Ontology' in B. Bashour and H. Muller (eds) Contemporary Philosophical Naturalism and its Implications (Routledge: London, 2013). [8] R. Porter, Ideology: Contemporary Social, Political and Cultural Theory (Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2006) and S. Malešević and I. MacKenzie (eds), Ideology After Poststructuralism (Oxford: Pluto Press, 2002). [9] G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (New York: Viking Press, 1977). This triangulation of the philosophers of suspicion, with a view to completing the Kantian project of critique, is one especially insightful way of reading this provocative text: see E. Holland, Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis (London: Routledge, 2002). by Glyn Daly

What can porn shoots tell us about the functioning of ideology? This can be approached through a critique of externalism. In externalist thinking there is always the image of a full presence, something substantial to which all distortion can be referred. In modern discourse, this is ultimately the position occupied by the (mythic) phallus: an autonomous self-sustaining One that stands apart and effectively overdetermines all relations of distortion: desire, narcissism, envy, and so on as so many orientations toward it.[1] Put in other terms, it reflects Jacques Derrida’s critical charge of phallogocentrism—where the symbolic order tends always to centre on notions of (masculinised) presence and identity—that he levels against psychoanalysis.[2] But what this misses is the way in which the privileging of the phallus in psychoanalysis is simultaneously a non-privileging. What the phallus names in psychoanalysis is essentially movement and/or treachery: gaining an erection when one least wants it and losing it when it is most required. Far from any autonomy or positivity of presence, the phallus reflects an autonomy of negativity. In other words, the phallus is “privileged” only insofar as it signifies lack as such. This is why Jacques Lacan repeatedly refers to the phallus as a “wanderer” and as “elsewhere”: that which denotes a permanent alibi at the very heart of the symbolic order. Indeed the whole of psychoanalysis can be seen as predicated on the basic absence not only of phallic consistency (a phallogo-decentrism in this sense) but also all externality.

It is this lack of externality that is reflected in porn shoots where, in order to get in “the zone”, male pornstars themselves typically have to resort to watching porn. Far from being a site of authentic sexual production, the porn shoot reflects a kind of game of mirrors, or metonymy of distortions, without any externality. The phallus in its “naked” form (as full presence) does not exist as such; it only ex-sists in its relation to an elsewhere, in referral to an Other site of imaginary existence (a fantasy scenario) where it finds its authentication. Nobody really has It (the phallus) and consequently there are no figures of ultimate phallic enjoyment blocking our access to full (and impossible) presence and identity. The problem of ideology, on the other hand, can be characterised in terms of a certain “phallic” anxiety. That is to say, ideology always retains some idea of an external figure who is somehow in possession of It and is thereby responsible for all the distortions (unemployment, crime, lack of resources, global viruses, and so on). In every instance there exists a projection of an image of a unitary identity (“the Jew”, “the Muslim”, “the Mexican”…) that is held to be responsible. It is here that we should locate today’s fashionable idea of “red pilling”—a reference to The Matrix where, in a metaphorical sense, one takes a red pill in order to perceive the truth behind all the surface distortions and deceptions. This is also what lies at the root of all those groups from QAnon and the “deep state” believers to the antivaxxers and even those who recently stormed the Capitol. In each case the same basic mythology is reflected: that behind the scenes there is an “intelligent design”, a Lacanian subject-supposed-to-know. This mythology is perfectly embodied in the current “Plandemic” conspiracy theory—i.e., the view that coronavirus and the vaccines have been designed for the purpose of enslaving humanity—which by definition implies the existence of a planning entity behind the global pandemic: an entity that must be exposed. Again we have the same motif of a unified Other at work: that the systemic beast (in all its abstraction, algorithmisation of power, and so on) is secretly ruled by a sovereign, a beastly sovereign perhaps. Across the spectrum of the various dark elite perspectives—Illuminati, shape-shifting reptilians, Fourth Reich, etc.—there exists a basic fantasmatic attempt to resurrect (res-erect?) the phallus: the sense of a full presence behind all the distortion, a prime mover that would explain the nature and functioning of the system. Nor is this mythology restricted to extreme right-wing conspiracy theory. Chomsky, for example, is famously dismissive of the idea of “speaking truth to power” affirming instead that “power knows the truth already, and is busy concealing it”.[3] In other words, there exists a power cabal (a master entity) that is operating at a point beyond distortion where truth is fully transparent and is consciously manipulated/distorted by that cabal in order to secure its underlying interests. Yet what Chomsky misses is the way in which power is itself subject to the same kind of illusions of transparency, rationality, holism, and so on. If we take Brexit, for example, it is not simply that power (however defined) has engaged in mass deception in order to secure its “objective economic interests”—the purely economic arguments for and against Brexit were essentially undecidable. The point is rather to see how, mediated through ideology, the pro-Brexit interests were themselves constituted in such a way as to be perceived as fully in accord with serving and advancing the “national interest”. There was/is nothing inauthentic about the idea that the UK will be better off once it is free from the shackles of the “Brussels’ dictatorship”. On the contrary, the authenticity of the pro-Brexit mobilisation derived from the sincerely held belief that Britain will be able to secure its integrity, reassert itself globally, and restore its national greatness (etc.). Consequently we should not seek to identify an ultimate, or positivistic, source of capitalist manipulation/distortion. There is no Capitalism (with a capital “c”) in this sense. Capitalism only functions historically in its “impure” forms: liberal, authoritarian, fascist, democratic, religious, secular, communist, and so on. In other words, there exist only distorted (fantasmatic) versions of capitalism, all of which rely on the same kind of fiction of an antagonism-free (neutral) capitalism that is best for “the people”. Marx already knew this, arguing that (along with the proletariat) the bourgeoisie are also subject to an entire mode of production in which they internalise, and are simultaneously motivated by, the dimensions of not only enrichment and narcissism, but also the greater good, work ethic, social opportunity, sacrifice, and so on. This is also how we should read Marx’s assertion that capital is essentially a social power: i.e., a way of reproducing the very sense of “the social” without any pre-given content or orientation. In Althusserian language, capital is a system in distortion that seeks to naturalise its basic principles through all of its adjectival (impure) forms. Capitalists, no less than porn actors, are equally inscribed into an economy of distortions that both enables and directs their very sense of agency. Far from the traditionalist view of straightforward deception and mystification, ideology functions rather as a certain kind of revelatory discourse of disclosure and unmasking—precisely as a way of protecting a substantialist notion of reality. Against the Deleuzian insight that that the mask does not hide anything except other masks, the ideological mission is always one of unmasking, of establishing a positive account. And it is in this context that Laclau’s view of ideology as the illusory concealment of basic lack needs to be supplemented. The ideological mechanism effectively consists of a double distortion.[4] On the one hand, there is the distortive illusion of a social fullness (Laclau) but on the other there exists a simultaneous reciprocal distortive illusion of an external obstacle to that fullness (deep state, dark elites, threatening-yet-inferior groups, and so on). The illusion of social rapprochement can only be sustained via its opposite: the identification of social blockage. In a Hegelian twist, the ideological illusion of an antagonism-free world is generated through antagonism itself. Far from blocking me from the full constitution of my identity, the presence of an enemy is the very condition for supporting an image of full identity. In the words of Blofeld in Spectre, the positive function of (ideologised) antagonism is to provide an “author of all your pain”, a determinant figure to which we can seek redress for pure antagonism (i.e., antagonism that resides at the very heart of all identity). This is why Lacan refers to the subject as constitutively split (the S-barred or $): the subject is divided in terms of a pure/inherent antagonism between its historical symbolic content and its transhistorical void, the persistence of radical negativity that thwarts all symbolic constitution. Mediated through ideology, antagonism thus becomes a way of protecting us from the traumatic knowledge that there is no author of our pain/blockage. Through the externalisation of antagonism (the construction of the Other-as-blockage) we avoid the unbearable inherency of pure antagonism as such. It is against this background that the radicality of Lacan’s critique of castrative anxiety can be discerned. In Freud, anxiety arises through an affect of generalised loss premised on castration: the sense of privation. Lacan, however, completely turns this around and affirms that what the subject fears is not the loss as such but rather the loss of the loss: that is, the loss of an externalised figure that is projected as the embodiment of loss, negativity, and/or the impossibility of Society. Without such a figure, the subject is faced with the radical anxiety of freedom: the anxiety that arises from the knowledge that we are not constrained by an exterior obstacle or big Other. This is also how we should approach Ernst Hoffmann’s story of the eponymous and uncanny “Sandman” who haunts and torments the tragic character of Nathaniel throughout his short life. For Freud, the Sandman embodies the archetypal castrating father—reflected in his unfathomable desire/demand “Eyes out, eyes out!” for an obscure alchemical ritual. Yet what ultimately destroys Nathaniel is not so much the Sandman (a projected image of blockage) but his own inability to act or come to terms with the intricacies and pressures of forging meaningful relationships with “flawed” human beings—it is precisely when the way is open to a romantic union with Clara that Nathaniel’s madness/anxiety descends and he shrinks back from the act, fatally hurling himself from the market gallery. In this respect, the Sandman functions rather as a figure that regulates a critical distance with the anxiety of freedom. So when Slavoj Žižek affirms in his classical formulation that the “function of ideology is not to offer us a point of escape from our reality but to offer us the social reality itself as an escape from some traumatic, real kernel”, the only (Hegelian) point to add here is that the ideological escape from the Real is supplied through the Real itself: that is, through a certain simulation of the Real, giving it a semblance—the various “Sandmen” of today’s interlopers, malefactors, enemies of the people, and so on—rendering it manageable in some way.[5] How do we get out of this predicament? Here perhaps Joseph Stalin provides some inadvertent help. Towards the end of his life, Stalin confided to Lavrentiy Beria (the head of the secret police during Stalin's leadership) "I'm so paranoid that I worry that I am plotting against myself". Since Freud, psychoanalysis has long been aware of how paranoia functions as a desperate attempt to overcome the feeling of inexistence: the subject constructs enemies as a way of (over-) confirming their identity and thus avoiding what Stephen Grosz calls the “catastrophe of indifference”, the sense of drifting away into the void.[6] Those suffering from paranoia are in fact passionately attached to their antagonistic constructs—as Lacan puts it, paranoiacs “love their delusions as they love themselves”.[7] The paranoiac invents a world in which they can continue to have and eat their cake. In paranoia, the subject strives to keep both the possibility of a resolution (full presence) and the obstacle(s) to it—the obstacle serves as support to the (illusory) resolution. So the problem with the paranoiac is that, in a way, they are not paranoid enough. That is to say, they still cling to the idea of some kind of resolution (however remote or abstract). The way to confront paranoia is not by addressing the validity of specific claims but virtually the opposite: to radicalise paranoia in the affirmation of a paranoia without enemies or resolution. So Stalin was right in a certain sense: the negation is precisely an inherent one, a reflection of an inward contradiction between the idea of oneself and its attendant void. At the same time, what Stalin was unable to do was to realise the emancipatory potential of accepting the traumatic truth of this fundamental contradiction—and in this regard he remained fully within the terms of ideology. In Hegel, an emancipatory path is only opened once we abandon the continuous attempts to overcome contradiction (auto-negativity) and instead inscribe this contradiction as the very “foundation” of existence. This is why for Hegel there can be no resolution, only reconciliation. [1] This traditional notion of the One functions in idealised terms: something external and indivisible, comprising a positive ground for substance in general [2] Phallogocentrism is a neologism (combining both phallocentrism and logocentrism) deployed by Derrida to designate a double privileging: the privileging of logos (a positive view of the symbolic order in which meaning appears as both immediate and directly communicable) within Western metaphysics, and within logos the privileging of the phallus (i.e. a dominant paradigm of universalised masculine presence, authority and priorities). [3] Chomsky cited in T. Eagleton (2016), ‘The Truth Speakers’, New Statesman (3 April 2016) [4] G. Daly (2021), ‘Obstacles and Distortions: A Speculative Approach to Ideology’, Journal of Political Ideologies (forthcoming). [5] S. Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 45. [6] S. Grosz, The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2013). [7] J. Lacan, The Psychoses (New York: Norton, 1993), 215. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed