by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

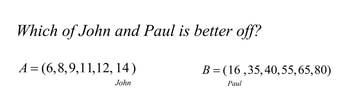

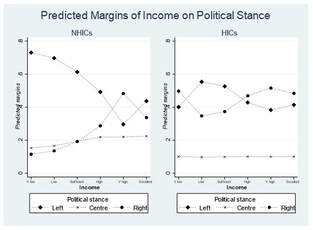

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

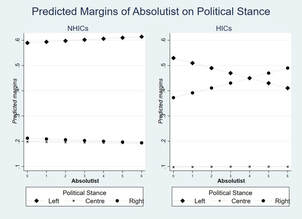

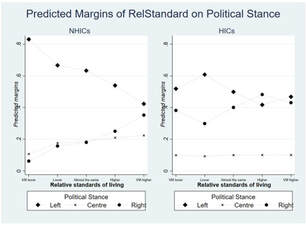

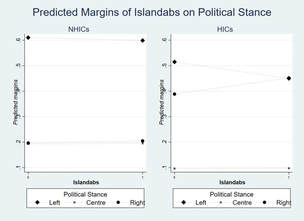

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. 6/12/2021 There is always someone more populist than you: Insights and reflections on a new method for measuring populism with supervised machine learningRead Now by Jessica Di Cocco

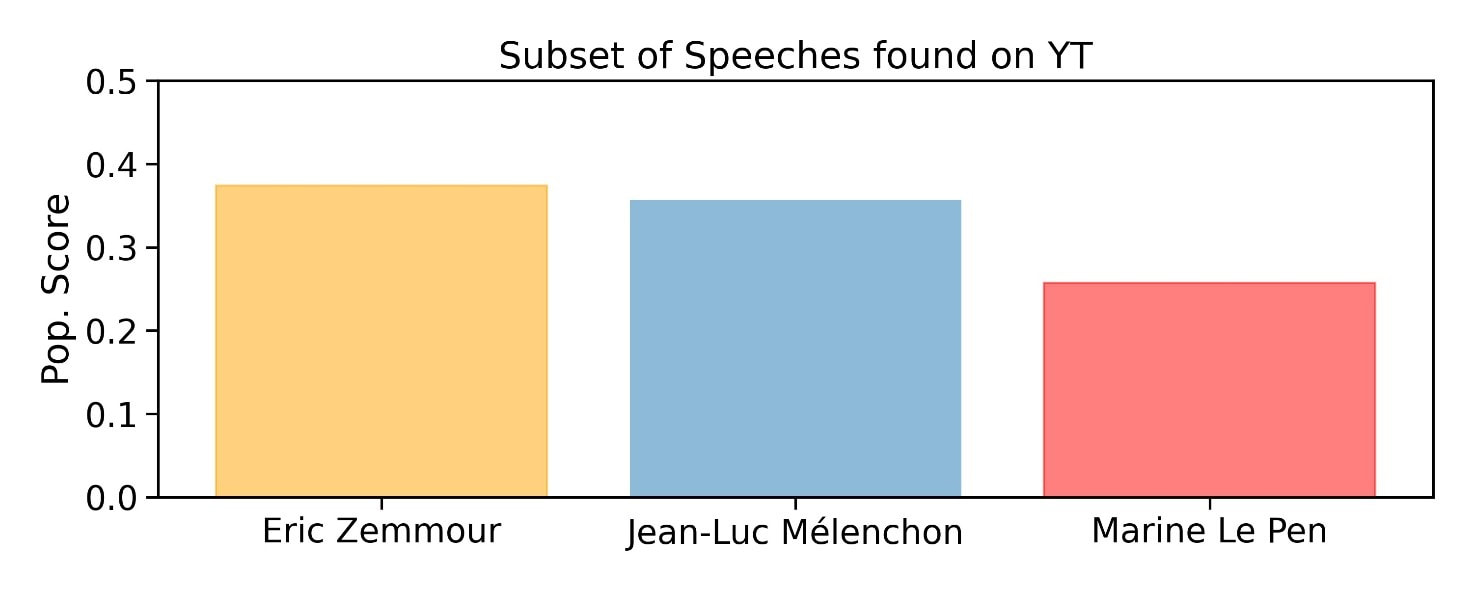

The debate on populism and its effects on society has been the subject of numerous studies in the social and non-social sciences. The interest in this topic has led an increasing number of scholars to analyse it from different perspectives, trying to grasp its facets and consider the national contexts in which populist phenomena have developed. The scholarly literature has increasingly highlighted the need to adopt empirical approaches to the study of populism, both looking at the supply side (i.e., how much populism political actors ‘offer’) and at the demand side (i.e., how much populism citizens and potential voters ‘demand’).[1] The transition from almost exclusively theoretical to quantitative studies on populism has been accompanied by several issues of no small importance concerning, for instance, problems of a statistical nature or related to data availability. From the point of view of the demand for populism, studies have shown that its determinants are numerous and often interconnected—ranging, for instance, from social status[2] to institutional trust,[3] from the deterioration of objective well-being[4] to perceptions of subjective well-being.[5] Analyses aimed at studying the causes and effects of populism generally come up against the statistical issues we mentioned earlier. Scientists familiar with empirical analyses might be aware of the problems of endogeneity, reverse causality, and omitted variables that can affect the reading of the final results. For example, the literature has often focused on the links between populism and crisis. However, the direction of what influences what (and, therefore, the causal relationship between them) remains controversial. As Benjamin Moffit has highlighted, rather than just thinking about the crisis as a trigger of populism, we should also consider how populism attempts to trigger the crisis. Populist actors participate in the ‘spectacularisation’ of failure underpinning crisis. Therefore, crises are not purely external to populism; they are internal key elements.[6] Another example concerns reverse causality. There is general agreement that economic conditions impact people’s voting choices. Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether facts or perceptions of these conditions impact more on voting choices. Larry Bartels has argued that it is not the actual economic conditions that matter, but rather that it is how this is interpreted by political parties that shapes perceptions.[7] Hence, there could be reverse causality at play, in which populist parties might impact wider perceptions of economic conditions.[8] From a populist supply perspective, studies have long focused on the classifications that scholars in the field have periodically drawn up.[9] Other scholars have gradually adopted alternative methods, such as focusing on the textual analysis of programmes, speeches, and other textual sources of leaders and parties. Our work is situated within this field of research on populism and, more generally, on ‘populisms’. We use the plural because we refer to different forms of populism that can develop along the entire ideological continuum and in very diverse national contexts. The diversity in the forms of populism has called for a deeper reflection on how we can compare them across the countries and measure them to consider the possible intensities and nuances. Measuring populism Indeed, one of the main challenges in comparative studies on populism is how to measure it across a large number of cases, including several countries and parties within countries. We address this issue in our recent work, in which we use supervised machine learning to evaluate the degrees of populism in evidence in party manifestos.[10] Previous literature had already explored the possibility of using different methods, including textual analysis,[11] [12] and machine learning has cleared the way for further research in this direction. What are the advantages of using automated text-as-data approaches for investigating diversified political questions, populism, and others? For example, these techniques allow for the analysis of large quantities of data with fewer resources, inferring actors’ positions directly from the texts, and obtaining more replicable results. Furthermore, they make it possible to focus on elites and their ideas,[13] and thereby obtain continuous populism measures which, unlike dichotomous ones, better account for the multi-dimensionality of populism and differentiate between its degrees.[14] Finally, automated textual approaches can help capture the rapid changes and transformations of the party landscape. We used automated textual analysis to derive a score which acts as a proxy for parties’ levels of populism. We validated the score using different expert surveys to check its robustness and verify the most correlated dimensions based on the literature on populism. We obtained a score that we can use to measure parties' levels of populism per year and across countries. In an ongoing study, we have applied the score for testing the Populist Zeitgeist hypothesis. According to Cas Mudde,[15] a populist Zeitgeist is spreading in Western Europe, which means that non-populist parties are becoming increasingly populist in their rhetoric in response to populists’ increasing success. We found that the entrance of populist contents into the debate within non-populist parties seems to be an Italian peculiarity. Prompted by this finding, we started investigating the possible issues connected with this specific trend and concluded that Italy has exhibited sharper decreases in crucial socio-economic dimensions, such as satisfaction with democracy, trust towards institutions, and objective and subjective well-being. For this exploratory analysis, we used data from European Social Survey[16] over the last two decades. The French case We can use the same method to investigate other textual sources and answer different questions within the field of populism analysis. For this purpose, we have collected a small corpus composed of 300 sentences drawn from TV interviews and debates available on YouTube and involving some of the candidates for the French Presidential Election that is due to take place in April 2022. The field of candidates is currently still somewhat unclear, since Eric Zemmour, an outsider leaning towards the far right who has enjoyed a degree of insurgent popularity in recent opinion polling, has not yet formally announced his candidacy. Given the limited availability of data, at the moment, we only focused on Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Marine Le Pen, and Eric Zemmour. Even if the corpus needs further improvement, we can already offer a number of interesting insights for more profound reflections and future studies. For those unfamiliar with French politics, the three leaders we chose for analysis exhibit radical and (or) populist traits. However, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen are already well-known to the general public, the third figure mentioned, Eric Zemmour, is new to the political scene. He has gained prominence chiefly as a controversial writer and columnist, politically positioned to the right of Marine Le Pen. Zemmour’s positions are so radical that they have succeeded in overtaking those of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National on the right, ranging from the theory of ‘ethnic replacement’ and anti-abortionism to the repeal of gay rights and nostalgia for the ‘golden age’ of French colonialism. Convicted several times for inciting racial hatred, he has recently be in court for his remarks on unaccompanied migrant minors. For this trial, he is accused of “complicity in provoking racial hatred” and “racial insult”. Interestingly, by comparison, when listening to Marine Le Pen speaking, she might appear almost moderate, if not progressive, even though she is a notoriously radical right-wing populist. Is this just a feeling, or is this the case? Undoubtedly, Zemmour’s racist and sexist statements would put many extreme right-wingers to shame, and he himself has described Le Pen as a ‘left-wing’ politician. At the same time, the familiar theories of electoral competition also teach us that the electoral arena is made up of spaces in which parties and their demands are located. On that basis, it cannot be ruled out that in the presence of such an ‘extreme’ candidate, Marine Le Pen may opt for (or find herself choosing) more moderate or progressive positions, while still maintaining her attachment to her ideology’s cardinal elements, such as anti-immigration arguments, anti-Islam positions, economic nationalism, and anti-establishment claims. In all of this, the figure of radical left-wing leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon stands out; at the time of writing this article, he is the only leader who has accepted a televised confrontation with Zemmour. Some interesting reflections also arise on how the extreme right and left can share aspects as for what they offer to their potential electorate, especially if the games are played out on populist terrain. To perform the analysis, we derived the scores by applying the methodology we proposed in our work. The algorithm that we use is capable of discriminating between sentences belonging to populist or non-populist parties of a given country. The final party score that we obtained is the fraction of sentences that the classifier considers as being more likely to belong to prototypically populist partisan speech in France. Therefore, the score measures the probability that a sentence is drawn from an speech of a prototypical French populist party. According to our analysis, Zemmour is the most populist leader, with Mélenchon close behind and Marine Le Pen increasingly isolated in the rankings (see Fig. 1 below). And Macron? What of the other candidates? At the time of writing, Macron has not yet officially launched his election campaign, limiting himself to giving speeches and interviews in his capacity as head of government rather than as a future presidential candidate. As for the other candidates, firstly they belong to more ideologically moderate parties; secondly, they are starting to give their first interviews at the time of writing. The association between moderate stances and anti-populism on the one hand, and extremism and populism on the other, is not new in the literature on populism to the extent that the terms ‘populist’ and ‘radical’ have been almost used interchangeably.[17] On the contrary, moderate parties tend to be anti-populist by nature, since they do not exhibit the traits that are typically attributed to populist actors (for example, anti-elitism, people-centrism, the Manichean worldview).[18] Although many French moderate parties have launched their electoral campaign, they are far from generating the same levels of public outcry as the three populists mentioned above. A clamour that seems to confirm the old saying that, as Oscar Wilde puts it, ‘there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about’. Even if it means finding out that there is always someone more populist than you. Conclusion For this article, we have limited ourselves to showing how our method based on supervised machine learning has allowed us to obtain quick and valuable results to start new analyses and reflections. However, we shall have to wait a little longer to build a complete and comprehensive corpus, and to validate our results with further speeches as they take place and enter French political discourse. There are many questions that deserve to be investigated in the coming months. How will the French electoral campaign evolve? Will the levels of populism increase as the presidential elections approach? Does our method allow us to distinguish between left- and right-wing populisms? Is it possible to calculate the distance (or proximity) between the various leaders’ substantive rhetoric? These are just some of the questions to ask ourselves as time goes on. We will try to provide some answers in the coming weeks and months, expanding our analysis to include new leaders, first and foremost the current President Macron, new speeches, and new validations. For now, it remains to be seen how far the populist clamour convinces others to shift in their direction. [1] Meijers, Maurits J., and Andrej Zaslove. "Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach." Comparative political studies 54.2 (2021): 372-407. [2] Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. "Populism as a problem of social integration." Comparative Political Studies 53.7 (2020): 1027-1059. [3] Algan, Yann, et al. "The European trust crisis and the rise of populism." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017.2 (2017): 309-400. [4] Guriev, Sergei. "Economic drivers of populism." AEA Papers and Proceedings. Vol. 108. 2018. [5] Guiso, Luigi, et al. Demand and supply of populism. London, UK: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2017. [6] Moffitt, Benjamin. "How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism." Government and Opposition 50.2 (2015): 189-217. [7] Bartels, Larry M. "Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions." Political behavior 24.2 (2002): 117-150. [8] van Leeuwen, Eveline S., and Solmaria Halleck Vega. "Voting and the rise of populism: Spatial perspectives and applications across Europe." Regional Science Policy & Practice 13.2 (2021): 209-219. [9] Van Kessel, Stijn. Populist parties in Europe: Agents of discontent?. Springer, 2015. [10] Di Cocco, Jessica, and Bernardo Monechi. "How Populist are Parties? Measuring Degrees of Populism in Party Manifestos Using Supervised Machine Learning." Political Analysis (2021): 1-17. [11] Jagers, Jan, and Stefaan Walgrave. "Populism as political communication style." European journal of political research 46.3 (2007): 319-345. [12] Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels. "Measuring populism: Comparing two methods of content analysis." West European Politics 34.6 (2011): 1272-1283. [13] Hawkins, Kirk A., et al. "Measuring populist discourse: The global populism database." EPSA Annual Conference in Belfast, UK, June. 2019. [14] Zaslove, A. S., and M. Meijers. "Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach." (2020). [15] Mudde, Cas. "The populist zeitgeist." Government and opposition 39.4 (2004): 541-563. [16] https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ [17] EUROPE, POPULIST RADICAL RIGHT PARTIES IN, and C. Mudde. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge university press, 2007. [18] Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. "The ideational approach to populism." Latin American Research Review 52.4 (2017): 513-528. Fig. 1: The ranking of the leaders based on their TV speeches and debates. The corpus is a sample of speeches, further sentences will be added to expand the analysis to other leaders and validate the results.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed