by Jack Foster and Chamsy el-Ojeili

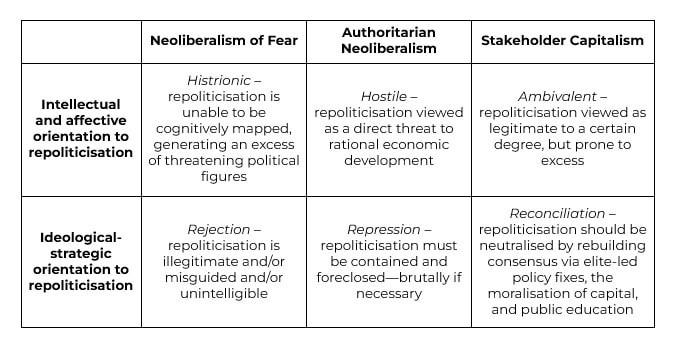

In September 2021, penning his last regular column for the Financial Times after 25 years of writing on global politics, Philip Stephens reflected on a bygone age. In the mid-1990s, an ‘age of optimism’, Stephens writes, ‘the world belonged to liberalism’. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the integration of China into the world economy, the realisation of the single market in Europe, the hegemony of the Third Way in the UK, and the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance presaged a century of ‘advancing democracy and a liberal economic order’. But today, following the financial crash of 2008 and its ongoing fallout, and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘policymakers grapple with a world shaped by an expected collision between the US and China, by a contest between democracy and authoritarianism and by the clash between globalisation and nationalism’.[1] Only five months later, the editors of the FT judged that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had definitively closed the ‘chapter of history opened by the fall of the Berlin Wall’; the sight of armoured columns advancing across the European mainland signals that a ‘new, darker, chapter has begun’.[2] At this juncture, with the all-consuming immediacy of the war in Ukraine, and the widespread appeal of framing the conflict in civilisational terms—Western liberal democracy facing down an archaic, authoritarian threat from the East—it is worth reflecting on some of the currents that flow beneath and give shape to the discourse of Western liberal elites today. In a previous essay, we argued that the leading public intellectuals and governance institutions of Western capitalism have struggled to effectively interpret and respond to the political and economic turmoil first unleashed by the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–2008.[3] We traced out a crisis of intellectual and moral leadership among Western elites in the splintering of (neo)liberal discourse over the past decade-and-a-half—the splintering of what was, prior to the GFC, a relatively consensual ‘moment’ in elite discourse, in which cosmopolitan neoliberalism had reigned supreme. As has been widely argued, the financial crisis brought this period of confidence and self-congratulation to an abrupt and unexpected halt. Both the enduring economic malaise that followed the crash, and the crisis of political legitimacy that has unfolded in its wake, have shaken the intellectual and ideological certitude of Western liberals. All political ideologies experience ‘kaleidoscopic refraction, splintering, and recombination’, as they are adapted to historical circumstances and combined with elements of other worldviews to produce novel formations.[4] However, we argued that the post-GFC period has seen a particularly intense and marked splintering of (neo)liberal discourse into three distinctive but overlapping and intertwining strands or ‘moments’. First, a neoliberalism of fear,[5] which is animated by the invocation of various dystopian threats such as populism, protectionism, and totalitarianism, and which associates the contemporary period with the extremism and instability of the 1930s. Second, a punitive neoliberalism, which seeks to conserve and reinforce existing power relations and institutions of governance.[6] And third, a pragmatic and reconciliatory neo-Keynesianism, oriented above all to saving capitalism from itself. In this essay, we want to expand upon one aspect of this analysis. Specifically, we suggest here that one way in which we can distinguish between these three strands or ‘moments’ is as distinct responses to the repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management in the years following the GFC. Respectively, these responses can be summarised as rejection, repression, and reconciliation (see Table 1, below). Depoliticisation and repoliticisation In our previous essay, we argued that the 1990s and early 2000s were marked by the predominance of cosmopolitan neoliberalism as a successful project of intellectual and moral leadership, the moment of the ‘end of history’ and ‘happy globalisation’. In this period, we saw the radical diminution of economic and social alternatives to capitalism, the colonisation of ever more spheres of social life by the market, the transformation of common sense around the proper relationship between states and markets, the public and the private, equality and freedom, the community and the individual, and the institutionalisation of post-political management, or what William Davies has called ‘the disenchantment of politics by economics’.[7] Of this last, neoliberalism, as both a political ideology and a set of institutions, has always been oriented to the active depoliticisation and indeed dedemocratisation of ‘the economy’ and its management—what Quinn Slobodian calls the ‘encasement’ of the market from the threat of democracy.[8] In practice, this has been pursued in two primary ways. First, it has been accomplished via the legal and institutional insulation of ‘the economy’ from democratic contestation. Here, the delegation of critical public policy decisions to unelected, expert agencies such as central banks and the formulation of rules-based economic policy frameworks designed to narrow political discretion are emblematic. Second, this has been buttressed by ideological appeals to the constraints placed upon domestic economic sovereignty by globalisation and the necessity of technocratic expertise in government—strategies that lay at the heart of the Clinton administration in the US (‘It’s the economy, stupid!’) and the Third Way of Tony Blair in the UK. Economic management was to be left to Ivy League economists, central bankers, and the financial wizards of Wall Street and the City. The so-called ‘Great Moderation’—the period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that was characterised by low macroeconomic volatility and sustained, albeit unspectacular, growth in most advanced economies—lent credence to these ideas. The hubris of elites in this period should not be underestimated. As Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the influential Bank for International Settlements, put it to an audience of European financiers in 2019, ‘During the Great Moderation, economists believed they had finally unlocked the secrets of the economy. We had learnt all that was important to learn about macroeconomics’.[9] And in his ponderous account of how global capitalism might be saved from the triple-threat of financial instability, Covid-19, and climate change, former governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney recalls ‘how different things were’ prior to the credit crash—a period of ‘seemingly effortless prosperity’ in which ‘Borders were being erased’.[10] The GFC catalysed both an epistemological crisis in mainstream economics, and, after some delay, the rise of anti-establishment political forces on both the left and the right. The widespread failure to reflate economic development in the wake of the crisis and the punishing effects of austerity in the UK and the Eurozone, and at the state level in the US, only exacerbated the problem. Over the past decade-and-a-half, questions of economic development, of who gets what, and of who should be in charge, have come back on the table. How have Western elites responded? Rejection One dominant response to this repoliticisation of ‘the economy’ and its management has been to invoke a host of dystopian figures—populism, nationalism, political extremism, protectionism, socialism, and totalitarianism—all of which are perceived as threats to the stability of the open-market order, to economic development, and to a thinly defined ‘liberal democracy’. This is the neoliberalism of fear Four years prior to the election of Donald Trump, the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks’ assessment was already grimly warning that the ‘seeds of dystopia’ were borne on the prevailing winds of ‘high levels of unemployment’, ‘heavily indebted governments’, and ‘a growing sense that wealth and power are becoming more entrenched in the hands of political and financial elites’ following the GFC.[11] In 2013, Eurozone technocrats were raising cautious notes around the ‘renationalisation of European politics’.[12] By 2015, Martin Wolf, long-time economics columnist for the FT, was informing his readers that ‘elites have failed and, as a result, elite-run politics are in trouble’.[13] This climate of fear reached fever-pitch in 2016, with the shocks delivered by the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, and again in January 2021, with mounting fears that President Biden’s inauguration would be blocked by a truculent Republican party. The utopian world of the long 1990s, in which globalisation was ‘tearing down barriers and building up networks between nations and individuals, between economies and cultures’, in the words of Bill Clinton, has thus disappeared precisely as ‘the economy’ and its management began to be repoliticised.[14] Two aspects of this often-histrionic neoliberalism of fear stand out. First, we see a striking inability to cognitively map the repoliticised terrain. Rather than serious attempts to map out why and in what ways repoliticisation is occurring, this strand or ‘moment’ is characterised by a reliance on a set of questionable historical analogies, above all the 1930s and the disasters of totalitarianism. Second, extraordinary weight is given over to these threats and fears, and there is a corresponding absence of serious attempts to construct a new ideological consensus. Instead, repoliticisation is countered in a language that is defensive, hectoring, and dismissive. For Wolf, populist forces have organised to ‘muster the inchoate anger of the disenchanted and the enraged who feel, understandably, that the system is rigged against ordinary people’.[15] In like fashion, former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, reflecting on his role in resolving the GFC, writes that in crises, ‘fear and anger and ignorance’ clouds the judgement of both the public and their representatives and impedes sensible policymaking; it is essential, in times of crisis, that decisions are left to coldly rational technicians.[16] Musing on the integration backlash in the EU, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, noted that while ‘protectionism is society’s natural response’ to unchecked market forces, it is crucial to ‘resist protectionist urges’, and this is the job of enlightened technocrats and politicians, who must hold back the populist forces threatening to roll back market integration.[17] In other words, while recognising that a rampaging globalisation has driven social and political unrest, within this neoliberalism of fear the masses are viewed as too capricious and ignorant to be trusted; the post-GFC malaise, while frightening and disorienting, will certainly not be solved by more democracy. Repression Closely related to, and overlapping with, this neoliberalism of fear is the second core strand or ‘moment’, that of a punitive and coercive neoliberalism. If the neoliberalism of fear can be understood as a dismissive overreaction to repoliticisation, this second strand represents a more direct and focused attempt to manage this new, more unstable, and more contested political economy. Fears of deglobalisation, of protectionism, of fiscal recklessness are also prominent in this line of argument; however, equally prominent are the necessary solutions: strengthening the rules-based global order, ongoing flexibilisation and integration of labour and product markets—particularly in the EU—and a harsh but altogether necessary process of fiscal consolidation. The problem of public debt has, of course, been one of the major battlegrounds here. Preaching the necessity of fiscal consolidation at the elite Jackson Hole conference in 2010, for example, Jean-Claude Trichet raised the cautionary tale of Japan, a country that ‘chose to live with debt’ in the 1980s and suffered a ‘lost decade’ in the 1990s as a result.[18] These concerns were widely echoed in the financial press and by international policy organisations; here, the threat of market discipline was also consistently evoked as justification for fiscal retrenchment and punishing austerity. As former IMF economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff infamously warned, prudent governments pay down public debt, because ‘market discipline can come without warning’.[19] Much has been made of the punitive, moralising, and post-hegemonic dimensions of this discourse.[20] However, it is worth bearing in mind that there are also genuine attempts to match the policy prescriptions associated with this more authoritarian and coercive neoliberalism—fiscal austerity, enhanced fiscal discipline and surveillance, structural adjustment, rules-based economic governance—with a positive vision of the political economy that these policies will deliver: economic growth, global economic stability, a route out of the post-GFC doldrums. Viewed in this way, the key ideological thrust here seems to be less that of punishment for punishment’s sake than it is of the deliberate repression and foreclosure of repoliticisation. Pace the classical neoliberal thinkers, the driving logic is that economic development and economic management are far too important to be left to democracy, which is altogether too fickle and too subject to capture by interest groups to be trusted. The upshot? Austerity, flexibilisation, the strengthening of the elusive rules-based global order: all this must be pushed through regardless of dissent. As with any ideological formation, shutting down alternative arguments is also important. As one speaker at the Economist’s 2013 ‘Bellwether Europe Summit’ put it, ‘the political challenge’ to structural adjustment ‘comes not from the process of adjustment itself. People can accept a period of hardship if necessary. It comes from the belief that there are better alternatives available that are being denied’.[21] In these ways, this second strand or ‘moment’ is directly hostile to the return of the political: less a hurried and defensive pulling-up of the drawbridge, as in the neoliberalism of fear, than a concerted counterattack. Reconciliation While this punitive and coercive neoliberalism seeks to repress repoliticisation by further insulating ‘the economy’ and its management from democratic interference, the third main strand of post-GFC (neo)liberal discourse responds to repoliticisation in a more measured way. In our previous writing on this issue, we referred to this strand or ‘moment’ as a pragmatic neo-Keynesianism, which promotes technocratic policy fixes aimed at lightly redistributing wealth and rebuilding the social contract. Over the past couple of years, we suggest, these more reconciliatory energies have coagulated into a relatively coherent ideological project, that of stakeholder capitalism.[22] Simultaneously, aided by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism of the 2010s has been discredited and has largely vanished from the pages of the financial press, the policy recommendations of the major international organisations, and the books and columns of Western public intellectuals. Thus, we use the term stakeholder capitalism to refer to the recent ideological shift in the Western policy establishment, among public intellectuals, and in business and high finance, that centres around the push for more ‘socially responsible’ corporations, for ‘green finance’, and for the re-moralisation of capitalism. By 2019, this shift was gathering momentum. Former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz implored readers of the New York Times to help build a ‘progressive capitalism’, ‘based on a new social contract between voters and elected officials, between workers and corporations, between rich and poor, and between those with jobs and those who are un- or underemployed’.[23] The FT launched its ‘New Agenda’, informing its readers that ‘Business must make a profit but should serve a purpose too’.[24] The American Business Roundtable, the crème de la crème of Fortune-500 CEOs, issued a new ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’, in which it revised its long-standing emphasis on promoting shareholder-value maximisation. Rather than narrowly focusing on returning profit to their shareholders, it now claims that corporations should ‘focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone—investors, employees, communities, suppliers, and customers’.[25] Similarly, the WEF launched its 50th-anniversary ‘Davos Manifesto’ on the purpose of a company, promoting the development of ‘shared value creation’, the incorporation of environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into company reporting and investor decision-making, and responsible ‘corporate global citizenship […] to improve the state of the world’.[26] And no lesser figure than Jaime Dimon, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank, noted in his 2019 letter to shareholders that ‘building shareholder value can only be done in conjunction with taking care of employees, customers and communities. This is completely different from the commentary often expressed about the sweeping ills of naked capitalism and institutions only caring about shareholder value’.[27] Now, in early 2022, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, has announced that it will be launching a ‘Center for Stakeholder Capitalism’ in the near future.[28] The term ‘stakeholder management’ was originally coined by the business-management theorist Edward Freeman in the 1980s,[29] but the roots of this discourse go back to the dénouement of the first Gilded Age, where some business leaders began to promote the idea of the socially responsible corporation as a means of outflanking working-class discontent during the Great Depression.[30] The concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ then became popular in the 1990s, associated above all with the Third Way of New Labour.[31] Today, the discourse of stakeholder capitalism has been resurrected and updated, we suggest, in direct response to the repoliticisation of the economy and its management and the failure of authoritarian neoliberalism to provide a way out of the post-2008 quagmire. At the root of this rebooted version of stakeholder capitalism is an argument for the re-moralisation of capitalism in the interests of social cohesion and long-term sustainability. To be sure, there remains a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, consumer choice, and so on. But there is also a recognition of—or at least the payment of lip service to—the fact that a rampaging globalisation and widespread commodification has undermined social stability and cohesion. Thus, in contrast to the second strand or ‘moment’ of post-GFC (neo)liberalism, stakeholder capitalism seeks to deal with the repoliticisation of the economy and its management by establishing a more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. To establish a more inclusive capitalism means making some relatively significant shifts in economic policy. ‘[T]argeted policies that achieve fairer outcomes’ are the order of the day.[32] A more fiscally active state and investment in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D are all called for. So too is an expanded social-welfare safety net, primarily in the form of active labour-market policies. And above all, stakeholder capitalism is about tackling the green-energy transition, which presents, for boosters of a private-finance-led transition, ‘the greatest commercial opportunity of our time’.[33] This means ‘smart’ state intervention to steer and ‘derisk’ private investment.[34] Cultural reform, economic education, and democratic renewal are also viewed as important enabling features of this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism. Here, policymakers must lead from the front, finding ways to better communicate with, and to educate, citizens and to foster consensus. In these respects, if the ‘moment’ of punitive and authoritarian neoliberalism was characterised by the repression of repoliticisation, then stakeholder capitalism seeks reconciliation. But while the legitimacy of democratic dissatisfaction is broadly recognised, and while there is a place for ‘more democracy’ in the discourse of stakeholder capitalism, this is democracy conceptualised not as the meaningful contestation of the distribution of power and resources, but as a relentless machine for building consensus. Opposing value systems and fundamental conflicts over the distribution of resources do not exist, only ‘stakeholder engagement’ oriented to revealing the ‘public interest’ or the preferences of ‘society’ at large. Exponents of stakeholder capitalism call for more education on how the economy works and emphasise the need to ‘listen’ more attentively to the citizenry. But the intention behind such endeavours is to develop or fortify consensus around already-existing institutions, or at best to tweak them at the margins. In these respects, there is an ambivalence running through this third—and perhaps now dominant—strand or ‘moment’: the mistrust of democracy, made explicit in the neoliberalism of fear and its authoritarian counterpart, is never completely out of the frame. Table 1: Rejection, repression, and reconciliation Horizons Despite its obvious limitations from the normative point of view of radical or even social democracy, the (re)emergent ideological formation of stakeholder capitalism does, we suggest, represent a relatively coherent attempt at rebuilding ideological consensus in Western societies. After years of intellectual and moral disorganisation, the rise to dominance of stakeholder capitalism among the policy establishment, high finance, some liberal intellectuals, and the financial press perhaps signals the reestablishment of intellectual and ideological discipline among elites. But it seems unlikely that this line of approach will bear fruit in the long run; the dysfunctions of the (neo)liberal world order—spiralling inequality and oligarchy, post-democratic withdrawal and outrage, resurgent nationalism, and anaemic, debt-dependent economic growth—run deep. More immediately, the war in Ukraine, and the unprecedented financial and economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers, threatens to once again reorder the ideological terrain and to intensify the shift away from globalisation. Perhaps the dominant response among (neo)liberal commentators thus far has been to frame the conflict as the first battle in a coming war for the preservation of liberal democracy: we are seeing the return of a more ‘muscular’ liberalism, reminiscent of the early years of the War on Terror.[35] Indeed, throughout modern history, war has served to restore liberalism’s ideological vigour; the conflict in Ukraine may yet prove to be a shot in the arm. [1] P. Stephens, ‘The west is the author of its own weakness’, Financial Times, 30 September 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9779fde6-edc6-4d4c-b532-fc0b9cad4ed9 [2] The Editorial Board, ‘Putin opens a dark new chapter in Europe’, Financial Times, 25 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a69cda07-2f63-4afe-aed1-cbcc51914105 [3] J. Foster and C. el-Ojeili, ‘Centrist Utopianism in Retreat: Ideological Fragmentation after the Financial Crisis’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 2021. [4][4] Q. Slobodian and D. Plehwe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Plehwe, Q. Slobodian, and P. Mirowski (Eds), Nine Lives of Neoliberalism (London: Verso, 2020), p. 3. [5] N. Schiller, ‘A liberalism of fear’, Cultural Anthropology, 27 October 2016, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-liberalism-of-fear [6] W. Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’, New Left Review, 101 (2016), pp. 121-134. [7] W. Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty, and the Logic of Competition, revised edition (London: Sage, 2017). [8] Q. Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018). The reduction of essentially political problems to their economic dimension is a long-standing feature of liberalism as such and is therefore not an original aspect of neoliberalism; it is, however, particularly pronounced in the latter. [9] C. Borio, ‘Central banking in challenging times’, speech at the SUERF Annual Lecture, Milan, 2019. [10] M. Carney, Value(s): Building a Better World for All (London: William Collins, 2021), p. 151. [11] World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2012 (Geneva: WEF, 2012), pp. 10, 19. [12] B. Cœuré, ‘The political dimension of European economic integration’, speech at the Ligue des droits de l’Homme, Paris, 2013. [13] M. Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What We Have Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis (London: Penguin, 2015), p. 382. [14] William Clinton, ‘President Clinton’s Remarks to the World Economic Forum (2000)’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOq1tIOvSWg [15] Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks, p. 383. [16] T. Geithner, Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises (London: Random House, 2014), p. 209. [17] M. Draghi, ‘Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2017. [18] J-C. Trichet, ‘Central banking in uncertain times – conviction and responsibility’, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 2010. [19] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times, 28 January 2010. [20] See, for example, Davies, ‘The new neoliberalism’. [21] J. Asmussen, ‘Saving the euro’, speech at the Economist's Bellwether Europe Summit, London, 2013. [22] J. Foster, ‘Mission-oriented capitalism’, Counterfutures 11 (2021), pp. 154-166. [23] J. Stiglitz, ‘Progressive capitalism is not an oxymoron’, New York Times, 19 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/opinion/sunday/progressive-capitalism.html [24] Financial Times, ‘FT sets the agenda with a new brand platform,’ Financial Times, 16 September 2019, https://aboutus.ft.com/press_release/ft-sets-the-agenda-with-new-brand-platform [25] Business Roundtable, ‘Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote “an economy that serves all Americans”’, 19 August 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [26] World Economic Forum, ‘Davos Manifesto 2020: The universal purpose of a company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution’, 2 December 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/davos-manifesto-2020-the-universal-purpose-of-a-company-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/ [27] J. Dimon, ‘Annual Report 2018: Chairman and CEO letter to shareholders’, 4 April 2019, https://reports.jpmorganchase.com/investor-relations/2018/ar-ceo-letters.htm?a=1 [28] L. Fink, ‘Larry Fink’s 2022 letter to CEOs: The power of capitalism’, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter [29] See E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984). [30] J. P. Leary, Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018), pp. 162-163. [31] For an early statement, see W. Hutton, The State We’re In (London: Random House, 1995). Freeman also wrote on the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ in the 1990s. It is notable that the drive to develop this more ‘inclusive’ capitalism is made in the absence of, and often disdain for, the key conditions that enabled Western social democracy to (briefly) thrive—namely, a more autarkic global political economy, mass political-party membership, high trade-union density, the ideological threat posed by Soviet communism, a more coherent and engaged public sphere, and stronger civil-society institutions. Further, exponents of stakeholder capitalism retain a strong aesthetic-ideological attachment to neoliberal ideals of self-actualisation, entrepreneurialism, market-enabled liberty, and so on. For these reasons, we suggest that its closest ideological cousin is the Third Way. [32] B. Cœuré, ‘The consequences of protectionism’, speech at the 29th edition of the workshop ‘The Outlook for the Economy and Finance’, Villa d’Este, Cernobbio, 2018. [33] Carney, Value(s), p. 339. [34] D. Gabor, ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52(3) (2021), pp. 429-459. [35] M. Wolf, ‘Putin has reignitied the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy’, Financial Times, 2 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b by Emmanuel Siaw

Although there is a popular drive towards a much-touted ‘pragmatic’ understanding of global events, an ideological theory of international relations has become more important due to the complexity of these events. This means the creation of new methodologies and conceptions to demonstrate that the adaptability and everydayness of ideologies has become even more essential in a dynamic world. One way of doing this is to treat ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. What this also means is to further enhance the bid to see ideologies as phenomena that are “necessary, normal, and [which] facilitate (and reflect) political action”.[1] In this piece, I argue that a contextualisation of socialism and classical liberalism into the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological debate, respectively, has been the ideological binary pervading Ghanaian politics since independence despite the changes in government and personnel.

Making a case for thought and action through ideological contextualisation Many African governments have not hidden their love for or association with existing macro-ideologies like liberalism, Marxism, and socialism. Yet, for most of the journey of ideological studies, since its beginnings with Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Africa has been overlooked due to the preoccupation with the assumption that African states have little room for policy manoeuvre due to foreign influence—a position captured in the extraversion and dependency arguments.[2] This has been consolidated by the view that the rhetoric and actions of policymakers do not conform to dominant ideologies, or external influences appear to override the ideological objectives of African governments. In this article, I argue against this position, emphasising that dependency is not akin to a lack of ideology; and demonstrate that ideology is indeed relevant in Ghanaian politics as it will be in the rest of Africa. What I suggest is that although the ideas of Ghanaian governments may not be pure or conform fully to the core tenets of existing macro-ideologies, paying attention to contextually relevant ideological variables and how they interact with macro-ideologies is a viable way of understanding the dynamic role of ideas in Ghanaian and African politics, in general. Several studies have shown that events and politics in Africa are as dynamic and interesting as politics elsewhere.[3] Hence, I agree with Thompson that “if the study of ideology helps political scientists to understand the politics of the West, then the same should also be true for post-colonial Africa. Any book seeking to explain the politics of this continent, therefore, needs to identify and explore the dominant ideologies that are at work in this environment”.[4] I first admit that the African context is unconventional and atypical. Unconventional because ideologies are embedded in context and the existing macro-ideologies evolved from contexts and situations outside the African conditions. Interestingly, in a lecture by Vijay Prashad (Indian historian) he demonstrated how India and China have integrated Euro-American ideologies, similar to the point I am making here.[5] Second, I acknowledge the tight spaces in terms of structural institutional constraints, history and the level of dependency of African states that makes it quite unique from the politics of the global North. Therefore, to embark on this analysis of ideology in an unconventional setting requires certain theoretical adjustments to reflect the dynamic conditions of the politics in African states. My approach to these adjustments is what I call an Ideological Contextualisation Framework (ICF). Ideological contextualisation is a coined concept that connotes that ideologies and ideological analyses should consider the immediate environment and historical experience of the cases being explored. It is inspired mainly by the works of Michael Freeden and Jonathan Leader Maynard on ideology. In the process of policy-making, large abstract political ideas must be translated into actual decisions, policy documents, plans, and programmes of action. To do that, ideological concepts need to be made to ‘fit’ a particular place, time, and cultural context. Part of this bid to make ideologies ‘practicable’ in different contexts flows from the field of comparative social and political thought to a more recent conception of comparative ideological morphology by Marius Ostrowski.[6] For instance, James McCain’s experimental analyses of scientific socialism in Ghana, published in 1975 and 1979, reveal that it does not conform to the assumptions of orthodox ‘African Socialism’.[7] Instead, what a leader like Nkrumah meant with this ideology was to exploit its political mobilisation feature within the Ghanaian cultural context. This is because it was a response to the needs at the time. Emphasis is, therefore, placed on the “native point of view” and “whatever that happens to be at any point in time”.[8] The essence of contextualising ideas is to avoid the analytical shortfalls dominant in the African context occasioned by analyses that focus on either the overbearing role of ideology, which leads to policy failures, or the non-existence of ideologies at all. These analyses fail to capture the dynamics of ideology and what falls in-between these extremes. While Ghana is unique, its conditions resemble what happens in many African countries. This year, Ghana’s celebrates 65 years of gaining its independence and of being the first sub-Saharan African country to do so in 1957. Since independence, there have been highs and lows on the development spectrum. Ghana has experienced military, authoritarian, civilian, and democratic governments over the last six and half decades. At independence, Ghana was among the most economically promising countries in the world, but the 2020 Human Development Index Report ranked Ghana 138th in the world. Ghana has not experienced a full-blown civil war or war with other countries but has had pockets of internal conflicts. Over the years, Ghana’s politics and policy-making have also been a dynamic mix of successes and challenges that characterises many African states. Just like many exegeses of politics in other African states, it is common to hear commentary in Ghana about how genuine commitment to ideology has ended or how it has lost its traction for understanding Ghanaian politics, especially after the Nkrumah era. In one of such instances Ransford Gyampo, in his study on Ghanaian youth, emphasises that ideology does very little in orienting party members, especially the youth.[9] He further insisted on ideological purity as a conduit for organising the youth members. However, scholars like George Bob-Milliar have argued that political parties supply ideologies for their better-informed members who vote based on ideological differences.[10] For Franklin Obeng-Odoom and Lindsay Whitefield, such ideological differences rarely exist as neoliberalism has become a supra-ideology that pervades the different ‘isms’ to which parties subscribe.[11] Although the challenge here lies in the mischaracterisation of ideology, the jury is still out on ideology and its role in Ghanaian politics, just like many other African countries. A recalibrated look at the history of Ghanaian politics from the perspective of contextualisation presents a situation where ideology stretches far beyond magniloquence. Ideology and the history of Ghanaian politics What I do here is to briefly explore Ghana’s political history and demonstrate that ideology is and has indeed been relevant to Ghanaian politics. This ideology is typified by the ideological dichotomy between Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, which has lasted from the late 1940s to date. As I will explain below, the late pre and early post-independence period was characterised by two groups: one led by Dr Kwame Nkrumah, leader of the Convention People’s Party (CPP) that eventually won independence for Ghana in 1957. On the other hand was the opposition United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC)—the party that brought Nkrumah to Ghana from London—led by Joseph Boakye Danquah, and later by Kofi Abrefa Busia and Simon Diedong Dombo. These two groups agreed and disagreed on many policy issues based on their ideologies and such duality has characterised Ghana’s political milieu since independence. I limit this discussion to the period from independence to the end of Kufuor’s administration in January 2009. The beginnings of the politics of ideas in Ghana was more profound during the late colonial period after the split between Kwame Nkrumah and other members of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) that manifested in the formation of different political parties till Nkrumah’s overthrow in 1966. After this split in 1949, Nkrumah formed the Conventions Peoples Party (CPP) and went ahead to win independence for Ghana in 1957. The UGCC, on the other hand, transformed into different parties which contested and lost to Nkrumah in all the pre and early post-independence elections (1951, 1954, 1956 and 1960).[12] On the internalised level, the two groups were split by their commitment to socialism, African socialism, scientific socialism, or what later came to be known as Nkrumaism for the CPP and classical liberalism or what came to be known as property-owning democracy for the UGCC. One thing to note here is that the changes in vocabularies, as mentioned above and a common feature across subsequent administrations, is a practical manifestation of the constant search not just for a vocabulary that fits the Ghanaian context but ideas that reflects the aspirations of governments. These party formation dynamics have even deeper ideological outcomes for the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo group on some key issues. For instance, beyond their internalised socialist ideas, the CPP had what they called ‘African personality’ while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred the ‘Ghanaian personality’ beyond classical liberalism. What the CPP or Nkrumah administration meant by ‘African personality’ was for “recognising that Africa now has its personality, its own history and its own culture and that it has made valuable contributions to world history and world culture”.[13] According to Nkrumah, ‘African personality’ was to demonstrate to the world Africa’s “optimism, cheerfulness and an easy, confident outlook in tackling the problems of life, but also disdain for vanities and a sense of social obligation which will make our society an object of admiration and of example”.[14] The Danquah-Busia-Dombo group introduced the idea of Ghanaian personality counter the CPP’s African personality. By Ghanaian personality, they meant “giving more meaning to this freedom [republican status] to express our innermost selves”.[15] This meaning was contextual as it was the period after two harsh laws were passed by the Nkrumah government, CPP. The Avoidance of Discrimination Act (ADA) of 1957 banned all regionally based political parties and forced all opposition parties to merge into the United Party (UP). The Preventive Detention Act (PDA) of 1958 allowed for people to be detained without trial for five years if their actions were deemed a threat to national security. For the opposition, the best way to project an African personality, in the spirit of freedom (decolonisation) and unity (African integration), was first to project a Ghanaian personality that prioritised the same rights. The two ideas—African and Ghanaian personality—represented their contextual aspirations and significantly impacted their policy preferences and approach. They manifested in policy differences in issues such as how and when independence should be granted, how much Ghana should be involved in the politics of other African states, perceptions about colonial metropoles and future relations with them, how to approach regional integration, economic diplomacy and foreign policy, in general. It also influenced the domestic development goals and approaches. To give some few policy examples, the CPP fundamentally wanted independence ‘now’ regardless of the consequences while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo wanted independence within the shortest possible period through what they perceived as legal and legitimate means. Parsimoniously on regional integration, while the CPP preferred rapid regional political unity on the continent with all African states, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred functional regional integration starting with economic and from within the West African subregion. In terms of domestic developmental approach, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group always preferred alternative routes to Nkrumah’s state-led and managed Import Substitution Industrialisation and common or state ownership. Throughout this period, the interpretation of ideological components such as economic independence was a key part of the ideologies of the two groups. Even though they both considered it a crucial concept, their interpretations varied, leading to some significant differences in policies and approaches. However, the growing power of contextual structures such as the Bretton Woods has occasioned similar ideas and policy path-dependence over time since the overthrow of Nkrumah in 1966. A cursory look at the IMF and World Bank interventions in Ghana since 1967 shows a common neoliberal trend in approaches to resuscitate Ghana’s economy. This has later accounted for some sort of ideological convergence that some scholars have identified in their study of Ghana’s Fourth Republic (since January 1993). For a developing country that is yet to address some of its basic needs, like infrastructure and education, there are points of convergence in terms of common components that address basic developmental needs. They translate into policies that can, in most cases, appear similar because they have similar inspirations. One of such examples is how even the different ideological factions within the CPP and other political parties acknowledged the need for independence and formed some sort of ideological convergence on that regardless of their fundamental ideological differences. This late colonial and early post-independence period of ideological dichotomy and similarities set the stage for subsequent administrations amidst variations. I explain these dynamics below. The National Liberation Council (NLC) that overthrew the CPP government pursued policies that showed ideological consistency with the anti-Nkrumah group, Danquah-Busia-Dombo. This was buttressed by the fact that a one-time opposition leader during the CPP administration, who later went into exile, Prof. Kofi Abrefa Busia, became a leading member of the administration and headed the Centre for Civic Education—an organisation responsible for public education on civil liberties and democracy. The administration shifted Ghana’s domestic and foreign policy based on that ideological dichotomy flowing from the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo debate. More instructively, they shifted to framing liberal-oriented development programmes and building stronger relations with the West—something the Nkrumah-led CPP administration was wary of. When the Progress Party (PP) took power in 1969, it continued what the NLC began after the overthrow of Nkrumah’s CPP in 1966. Led by Prof. Busia himself, the PP government pursued policies that were ideologically at variance with Nkrumah but in line with ideas espoused by the UGCC before independence. For instance, the belief in non-violent decolonisation occasioned their policy to discontinue Ghana’s financial support for the African nationalists in South Africa, preferring dialogue with apartheid South Africa instead. In 1969, the Aliens Compliance Order promulgated by the government to return undocumented migrants affected many Africans and had implications for Ghana-Nigeria relations under subsequent governments had to address. For instance, in 1983 the Shehu Shagari government of Nigeria’s decision to deport undocumented migrants (half of the about three million deportees were Ghanaians) was popularly interpreted as a retaliation for Ghana’s 1969 deportation policy.[16] Although economic reasons were cited for Nigeria’s decision, it is obvious that what Ghana, or the PP government did in 1969 made the Nigerian government and people more relentless to follow through with their decision in what came to be known popularly as ‘Ghana must go’—a name also associated with the type of bag the migrants travelled with.[17] Based on Nkrumah’s relations with African settlers, the Aliens Compliance Order is a policy the CPP government would not have embarked on or fully encouraged.[18] Under the CPP government, Ghana was touted as the Mecca for African nationalists due to the government’s warm reception. Another point of difference between the two groups was the disagreement of large-scale industries of Nkrumah and the role of the state their building and operation. Therefore, a lot of Nkrumah’s industries were either discontinued or privatised. Some of these industries include the Glass Manufacturing Company at Aboso, in the Western Region, GIHOC Fibre Products Company and the Tema Food Complex Corporation, both in the Greater Accra Region.[19] The PP government was overthrown by an Nkrumaist oriented junta, the National Redemption Council (NRC), who tried to restore Ghana to its putative glorious years under Nkrumah by resuming Ghana’s contribution to African nationalist movement against Apartheid South Africa, supporting African states in several endeavours, resuming Nkrumah’s industrialisation agenda, pursing a domestication policy that aims to at food self-sufficiency, and repudiating foreign (especially Western) debts. These policies were grounded in the contextual ideological components of economic independence and Pan-Africanism, whose interpretations were closer to the CPP administration’s intentions. This Acheampong-led NRC government, and later Supreme Military Council (SMC I) administration, was overthrown by an Edward Akuffo-led Supreme Military Council (SMC II) who, though they orchestrated a palace coup to overthrow Acheampong, did not deviate much from the previous administration’s pro-Nkrumah policies. Instead, they were more focused on restoring Ghana to multiparty elections. However, this administration lasted for only eleven months and was overthrown by a group of young militants, the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), who took power until after the 1979 elections and handed over to a democratically-elected People’s National Party (PNP). The PNP government, led by Dr Hilla Limann, was one of the latter attempts to bring introduce a full-fledged Nkrumaist party after the CPP was banned before the 1969 elections. Although to the disappointment of many Nkrumaists, this government did not pursue politics based on the ideas of Nkrumah’s CPP, its policies were somewhat closer to what the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred—for instance, in attempting to the IMF for bailouts and broader pro-West economic relations. This was one of the reasons why the Rawlings-led military junta, now the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), returned to overthrow the PNP government in 1981. Although this group (PNDC) was generally touted as radical and anti-West, their internal ideological dynamics resembled the broader ideological dichotomy between the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo groups. Within the PNDC government was a group that aligned itself to Nkrumah’s CPP ideology and, for instance, were wary of the West, former colonial metropoles and programmes like the Structural Adjustment Policies. On the other side were those who were touted as less radical and ideologically closer to the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, who were rather willing to engage the World Bank and IMF through the Structural Adjustment Programmes. This internal dialectic shaped the government’s domestic and foreign policy. However, from 1984, there seemed to be a broader consensus within the party as one whose ideology and politics was shaped by contextual structures, which made it difficult for the government to pursue policies just based on its internalised ideology. The PNDC later metamorphosed into the National Democratic Congress (NDC) when the government, under several domestic and international pressures, adopted multiparty democracy and elections from December 1992. After leading Ghana democratically for eight years, the NDC lost the December 2000 elections to the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Coming directly from the Danquah-Busia-Dombo tradition, the NPP government led by John Agyekum Kufuor pursued policies mainly in line with what the forerunners have proffered, especially against Nkrumah’s policies. For instance, they created an enabling environment for private property ownership and entrepreneurial development, including encouraging foreign investors, a strengthened relationship with the West, and for a greater emphasis on its economic and democratic values. To further the idea of Ghanaian personality that was based on respect for humanity and human rights, the government opened itself up for review by other African states through the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), and took steps to pursue regional integration from a functional economic perspective. From the discussions above, a few things must be clarified regarding Ghana’s ideological history. Socialism (for Nkrumaists) and classical liberalism (for the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group) have been the two dominant internalised macro-ideological leanings in Ghana, since independence. However, in an ever-changing, developing, and dynamic context like Ghana and the rest of Africa, these ideologies cannot function in their pure form, in their influence on policies. Therefore, in Ghana and Africa, I argue that context matters. Looking at the Ghanaian case teaches us three main things analytically about the African continent. First is the dominance macro-ideologies or the fact that we cannot ignore ideologies like liberalism, Marxism and socialism as they are usually primary to the ideological structure of many governments. Second is the power and relevance of contextual structures, like regional organisations and the Bretton Woods, to produce ideas that African governments take on or adjust to because of their putatively weaker position. Constructivists have long emphasised the learning function of states. Third is existence of historical conditions that have evolved into ideas over time. Chatterjee Miller’s study of India and China’s foreign policy reveals a longue durée ‘post-imperial ideology’, comprising a sense of victimisation and driven by the goal of recognition and empathy as a victim of the international system to maximise territorial sovereignty and status.[20] In the Ghanaian case, some of these conditions include economic independence, Africa consciousness and good neighbourliness. While these conditions pervade across different governments, the interpretations and approaches vary. Across the continent, these conditions of ideological value may vary, but they are very relevant to any analysis of ideology. This affords us the laxity to focus on ideological components, treating the macro-ideologies as part of the components. One of the reasons why ideology has been overlooked is the assumption that African states are weaker and have very little policy options because a lot of their policies are dictated by foreign powers. However, looking at ideology in itself is a bid to explore existing spaces, shed more light on those that have so far been neglected, and begin analyses of African politics from a perspective that acknowledges a certain contextual relevance and policy constraints. To do this, we should see ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. Conclusion The place of ideology in global politics has been evolving in methodologies and vocabularies. This article is borne out of the bid to take Africa more seriously in that conversation by paying more attention to the contextualisation of ideas. This is not to say that ideologies explain everything, but it is to highlight the relationship between the interpretive value of ideology and contexts, and to emphasise that such relationships have a significant effect on African politics. The Ghanaian ideological context has been dominated by different shades of the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological dichotomy, characterised by an interaction between big-isms, contextual components and structures. These varieties of Ghanaian nationalism is bound to manifest differently in other African cases, but its conceptual proposition of interaction between context and ideas is very relevant. It demonstrates an understanding of African politics from within. Therefore, while this application gives us an indication and confidence to probe more into ideologies and policy-making in other African states, it also responds to the agency question which is fundamental to domestic and foreign policies. [1] Freeden, M. (2006). Ideology and Political Theory. Journal of Political Ideologies, 11(1), p. 19. [2] Bayart, J. F. (2000). Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion. African Affairs, 99, 217–267; Robertson, J., & East, M. A. (Eds.). (2005). Diplomacy and Developing Nations: Post-Cold War Foreign-Policy Structures and Processes. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [3] Brown, W., & Harman, S. (Eds.). (2013). African Agency in International Politics. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [4] Thompson, A. (2016). An Introduction to African Politics. In Routledge Handbook of African Politics (4th Edition). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p. 32. [5] Vijay Prashad (2021) What's the Left to Do in a World on Fire? | China and the Left. Public Lecture Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vd8w3ONjv6Y&t=453s Accessed 13th March 2022 [6] Ostrowski, M. S. (2022). Ideology Studies and Comparative Political Thought. Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), 1–10. [7] McCain, J. (1975). Ideology in Africa: Some Perceptual Types. African Studies Review, 18(1), 61–87; McCain, J. (1979). Perceptions of Socialism in Post-Socialist Ghana: An Experimental Analysis. African Studies Review, 22(3), p. 45. [8] Ibid, p. 46 [9] Gyampo, R. E. Van. (2012). The Youth and Political Ideology in Ghanaian Politics: The Case of the Fourth Republic. Africa Development, XXXVII(2), 137–165. [10] Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2012). Political Party Activism in Ghana: Factors Influencing the Decision of the Politically Active to Join a Political Party. Democratization, 19(4), 668–689. [11] Whitfield, L. (2009). “Change for a Better Ghana”: Party Competition, Institutionalisation and Alternation in Ghana’s 2008 Elections. African Affairs, 108(433), 621–641; Obeng-Odoom, F. (2013). The Nature of Ideology in Ghana’s 2012 Elections. Journal of African Elections, 12(2), 75–95 [12] Frempong, A. K. D. (2017). Elections in Ghana (1951-2016). In Ghana Elections Series (2nd Edition). Digibooks. [13] Potekhin, I. (1968). Pan-Africanism and the struggle of the Two Ideologies. Communist, p. 39. [14] Kwame Nkrumah: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 4th July, 1960, col. 19 [15] S. D. Dombo: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 30th June 1960, col. 250 [16] Aluko, O. (1985). The Expulsion of Illegal Aliens from Nigeria: A Study in Nigeria’s Decision-Making. African Affairs, 84(337), 539–560. [17] Graphic Showbiz (21st May, 2020) Ghana Must Go: The ugly history of Africa’s most famous bag. Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/entertainment/features/ghana-must-go-the-ugly-history-of-africa-s-most-famous-bag.html#&ts=undefined Accessed 13th March 2022 [18] Although in 1954, when Nkrumah was the Prime Minister and three years before Ghana’s independence, some Nigerians were deported; but not on the scale, in terms of number and government’s involvement, of what happened in 1969. After independence, Nkrumah’s support for African immigrants and other African states seems to have overshadowed the 1954 deportation of Nigerians. [19] Ghana News Agency (28th September 2020) Ghana: 'Revive Nkrumah's Industries'. Retrieved from https://allafrica.com/stories/202009280728.html Accessed 13th March 2022 [20] Miller, C. M. (2013). Post-Imperial Ideology and Foreign Policy in India and China. Stanford University Press. by Joanne Paul