by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

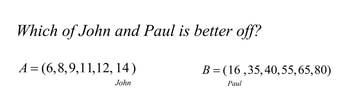

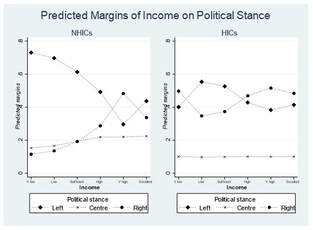

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

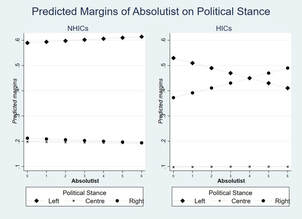

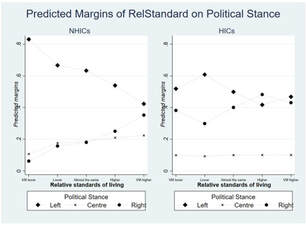

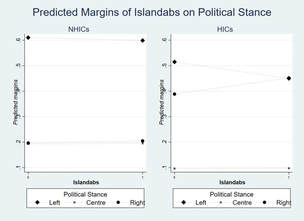

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. by Emmanuel Siaw

Although there is a popular drive towards a much-touted ‘pragmatic’ understanding of global events, an ideological theory of international relations has become more important due to the complexity of these events. This means the creation of new methodologies and conceptions to demonstrate that the adaptability and everydayness of ideologies has become even more essential in a dynamic world. One way of doing this is to treat ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. What this also means is to further enhance the bid to see ideologies as phenomena that are “necessary, normal, and [which] facilitate (and reflect) political action”.[1] In this piece, I argue that a contextualisation of socialism and classical liberalism into the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological debate, respectively, has been the ideological binary pervading Ghanaian politics since independence despite the changes in government and personnel.

Making a case for thought and action through ideological contextualisation Many African governments have not hidden their love for or association with existing macro-ideologies like liberalism, Marxism, and socialism. Yet, for most of the journey of ideological studies, since its beginnings with Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Africa has been overlooked due to the preoccupation with the assumption that African states have little room for policy manoeuvre due to foreign influence—a position captured in the extraversion and dependency arguments.[2] This has been consolidated by the view that the rhetoric and actions of policymakers do not conform to dominant ideologies, or external influences appear to override the ideological objectives of African governments. In this article, I argue against this position, emphasising that dependency is not akin to a lack of ideology; and demonstrate that ideology is indeed relevant in Ghanaian politics as it will be in the rest of Africa. What I suggest is that although the ideas of Ghanaian governments may not be pure or conform fully to the core tenets of existing macro-ideologies, paying attention to contextually relevant ideological variables and how they interact with macro-ideologies is a viable way of understanding the dynamic role of ideas in Ghanaian and African politics, in general. Several studies have shown that events and politics in Africa are as dynamic and interesting as politics elsewhere.[3] Hence, I agree with Thompson that “if the study of ideology helps political scientists to understand the politics of the West, then the same should also be true for post-colonial Africa. Any book seeking to explain the politics of this continent, therefore, needs to identify and explore the dominant ideologies that are at work in this environment”.[4] I first admit that the African context is unconventional and atypical. Unconventional because ideologies are embedded in context and the existing macro-ideologies evolved from contexts and situations outside the African conditions. Interestingly, in a lecture by Vijay Prashad (Indian historian) he demonstrated how India and China have integrated Euro-American ideologies, similar to the point I am making here.[5] Second, I acknowledge the tight spaces in terms of structural institutional constraints, history and the level of dependency of African states that makes it quite unique from the politics of the global North. Therefore, to embark on this analysis of ideology in an unconventional setting requires certain theoretical adjustments to reflect the dynamic conditions of the politics in African states. My approach to these adjustments is what I call an Ideological Contextualisation Framework (ICF). Ideological contextualisation is a coined concept that connotes that ideologies and ideological analyses should consider the immediate environment and historical experience of the cases being explored. It is inspired mainly by the works of Michael Freeden and Jonathan Leader Maynard on ideology. In the process of policy-making, large abstract political ideas must be translated into actual decisions, policy documents, plans, and programmes of action. To do that, ideological concepts need to be made to ‘fit’ a particular place, time, and cultural context. Part of this bid to make ideologies ‘practicable’ in different contexts flows from the field of comparative social and political thought to a more recent conception of comparative ideological morphology by Marius Ostrowski.[6] For instance, James McCain’s experimental analyses of scientific socialism in Ghana, published in 1975 and 1979, reveal that it does not conform to the assumptions of orthodox ‘African Socialism’.[7] Instead, what a leader like Nkrumah meant with this ideology was to exploit its political mobilisation feature within the Ghanaian cultural context. This is because it was a response to the needs at the time. Emphasis is, therefore, placed on the “native point of view” and “whatever that happens to be at any point in time”.[8] The essence of contextualising ideas is to avoid the analytical shortfalls dominant in the African context occasioned by analyses that focus on either the overbearing role of ideology, which leads to policy failures, or the non-existence of ideologies at all. These analyses fail to capture the dynamics of ideology and what falls in-between these extremes. While Ghana is unique, its conditions resemble what happens in many African countries. This year, Ghana’s celebrates 65 years of gaining its independence and of being the first sub-Saharan African country to do so in 1957. Since independence, there have been highs and lows on the development spectrum. Ghana has experienced military, authoritarian, civilian, and democratic governments over the last six and half decades. At independence, Ghana was among the most economically promising countries in the world, but the 2020 Human Development Index Report ranked Ghana 138th in the world. Ghana has not experienced a full-blown civil war or war with other countries but has had pockets of internal conflicts. Over the years, Ghana’s politics and policy-making have also been a dynamic mix of successes and challenges that characterises many African states. Just like many exegeses of politics in other African states, it is common to hear commentary in Ghana about how genuine commitment to ideology has ended or how it has lost its traction for understanding Ghanaian politics, especially after the Nkrumah era. In one of such instances Ransford Gyampo, in his study on Ghanaian youth, emphasises that ideology does very little in orienting party members, especially the youth.[9] He further insisted on ideological purity as a conduit for organising the youth members. However, scholars like George Bob-Milliar have argued that political parties supply ideologies for their better-informed members who vote based on ideological differences.[10] For Franklin Obeng-Odoom and Lindsay Whitefield, such ideological differences rarely exist as neoliberalism has become a supra-ideology that pervades the different ‘isms’ to which parties subscribe.[11] Although the challenge here lies in the mischaracterisation of ideology, the jury is still out on ideology and its role in Ghanaian politics, just like many other African countries. A recalibrated look at the history of Ghanaian politics from the perspective of contextualisation presents a situation where ideology stretches far beyond magniloquence. Ideology and the history of Ghanaian politics What I do here is to briefly explore Ghana’s political history and demonstrate that ideology is and has indeed been relevant to Ghanaian politics. This ideology is typified by the ideological dichotomy between Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, which has lasted from the late 1940s to date. As I will explain below, the late pre and early post-independence period was characterised by two groups: one led by Dr Kwame Nkrumah, leader of the Convention People’s Party (CPP) that eventually won independence for Ghana in 1957. On the other hand was the opposition United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC)—the party that brought Nkrumah to Ghana from London—led by Joseph Boakye Danquah, and later by Kofi Abrefa Busia and Simon Diedong Dombo. These two groups agreed and disagreed on many policy issues based on their ideologies and such duality has characterised Ghana’s political milieu since independence. I limit this discussion to the period from independence to the end of Kufuor’s administration in January 2009. The beginnings of the politics of ideas in Ghana was more profound during the late colonial period after the split between Kwame Nkrumah and other members of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) that manifested in the formation of different political parties till Nkrumah’s overthrow in 1966. After this split in 1949, Nkrumah formed the Conventions Peoples Party (CPP) and went ahead to win independence for Ghana in 1957. The UGCC, on the other hand, transformed into different parties which contested and lost to Nkrumah in all the pre and early post-independence elections (1951, 1954, 1956 and 1960).[12] On the internalised level, the two groups were split by their commitment to socialism, African socialism, scientific socialism, or what later came to be known as Nkrumaism for the CPP and classical liberalism or what came to be known as property-owning democracy for the UGCC. One thing to note here is that the changes in vocabularies, as mentioned above and a common feature across subsequent administrations, is a practical manifestation of the constant search not just for a vocabulary that fits the Ghanaian context but ideas that reflects the aspirations of governments. These party formation dynamics have even deeper ideological outcomes for the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo group on some key issues. For instance, beyond their internalised socialist ideas, the CPP had what they called ‘African personality’ while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred the ‘Ghanaian personality’ beyond classical liberalism. What the CPP or Nkrumah administration meant by ‘African personality’ was for “recognising that Africa now has its personality, its own history and its own culture and that it has made valuable contributions to world history and world culture”.[13] According to Nkrumah, ‘African personality’ was to demonstrate to the world Africa’s “optimism, cheerfulness and an easy, confident outlook in tackling the problems of life, but also disdain for vanities and a sense of social obligation which will make our society an object of admiration and of example”.[14] The Danquah-Busia-Dombo group introduced the idea of Ghanaian personality counter the CPP’s African personality. By Ghanaian personality, they meant “giving more meaning to this freedom [republican status] to express our innermost selves”.[15] This meaning was contextual as it was the period after two harsh laws were passed by the Nkrumah government, CPP. The Avoidance of Discrimination Act (ADA) of 1957 banned all regionally based political parties and forced all opposition parties to merge into the United Party (UP). The Preventive Detention Act (PDA) of 1958 allowed for people to be detained without trial for five years if their actions were deemed a threat to national security. For the opposition, the best way to project an African personality, in the spirit of freedom (decolonisation) and unity (African integration), was first to project a Ghanaian personality that prioritised the same rights. The two ideas—African and Ghanaian personality—represented their contextual aspirations and significantly impacted their policy preferences and approach. They manifested in policy differences in issues such as how and when independence should be granted, how much Ghana should be involved in the politics of other African states, perceptions about colonial metropoles and future relations with them, how to approach regional integration, economic diplomacy and foreign policy, in general. It also influenced the domestic development goals and approaches. To give some few policy examples, the CPP fundamentally wanted independence ‘now’ regardless of the consequences while the Danquah-Busia-Dombo wanted independence within the shortest possible period through what they perceived as legal and legitimate means. Parsimoniously on regional integration, while the CPP preferred rapid regional political unity on the continent with all African states, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred functional regional integration starting with economic and from within the West African subregion. In terms of domestic developmental approach, the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group always preferred alternative routes to Nkrumah’s state-led and managed Import Substitution Industrialisation and common or state ownership. Throughout this period, the interpretation of ideological components such as economic independence was a key part of the ideologies of the two groups. Even though they both considered it a crucial concept, their interpretations varied, leading to some significant differences in policies and approaches. However, the growing power of contextual structures such as the Bretton Woods has occasioned similar ideas and policy path-dependence over time since the overthrow of Nkrumah in 1966. A cursory look at the IMF and World Bank interventions in Ghana since 1967 shows a common neoliberal trend in approaches to resuscitate Ghana’s economy. This has later accounted for some sort of ideological convergence that some scholars have identified in their study of Ghana’s Fourth Republic (since January 1993). For a developing country that is yet to address some of its basic needs, like infrastructure and education, there are points of convergence in terms of common components that address basic developmental needs. They translate into policies that can, in most cases, appear similar because they have similar inspirations. One of such examples is how even the different ideological factions within the CPP and other political parties acknowledged the need for independence and formed some sort of ideological convergence on that regardless of their fundamental ideological differences. This late colonial and early post-independence period of ideological dichotomy and similarities set the stage for subsequent administrations amidst variations. I explain these dynamics below. The National Liberation Council (NLC) that overthrew the CPP government pursued policies that showed ideological consistency with the anti-Nkrumah group, Danquah-Busia-Dombo. This was buttressed by the fact that a one-time opposition leader during the CPP administration, who later went into exile, Prof. Kofi Abrefa Busia, became a leading member of the administration and headed the Centre for Civic Education—an organisation responsible for public education on civil liberties and democracy. The administration shifted Ghana’s domestic and foreign policy based on that ideological dichotomy flowing from the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo debate. More instructively, they shifted to framing liberal-oriented development programmes and building stronger relations with the West—something the Nkrumah-led CPP administration was wary of. When the Progress Party (PP) took power in 1969, it continued what the NLC began after the overthrow of Nkrumah’s CPP in 1966. Led by Prof. Busia himself, the PP government pursued policies that were ideologically at variance with Nkrumah but in line with ideas espoused by the UGCC before independence. For instance, the belief in non-violent decolonisation occasioned their policy to discontinue Ghana’s financial support for the African nationalists in South Africa, preferring dialogue with apartheid South Africa instead. In 1969, the Aliens Compliance Order promulgated by the government to return undocumented migrants affected many Africans and had implications for Ghana-Nigeria relations under subsequent governments had to address. For instance, in 1983 the Shehu Shagari government of Nigeria’s decision to deport undocumented migrants (half of the about three million deportees were Ghanaians) was popularly interpreted as a retaliation for Ghana’s 1969 deportation policy.[16] Although economic reasons were cited for Nigeria’s decision, it is obvious that what Ghana, or the PP government did in 1969 made the Nigerian government and people more relentless to follow through with their decision in what came to be known popularly as ‘Ghana must go’—a name also associated with the type of bag the migrants travelled with.[17] Based on Nkrumah’s relations with African settlers, the Aliens Compliance Order is a policy the CPP government would not have embarked on or fully encouraged.[18] Under the CPP government, Ghana was touted as the Mecca for African nationalists due to the government’s warm reception. Another point of difference between the two groups was the disagreement of large-scale industries of Nkrumah and the role of the state their building and operation. Therefore, a lot of Nkrumah’s industries were either discontinued or privatised. Some of these industries include the Glass Manufacturing Company at Aboso, in the Western Region, GIHOC Fibre Products Company and the Tema Food Complex Corporation, both in the Greater Accra Region.[19] The PP government was overthrown by an Nkrumaist oriented junta, the National Redemption Council (NRC), who tried to restore Ghana to its putative glorious years under Nkrumah by resuming Ghana’s contribution to African nationalist movement against Apartheid South Africa, supporting African states in several endeavours, resuming Nkrumah’s industrialisation agenda, pursing a domestication policy that aims to at food self-sufficiency, and repudiating foreign (especially Western) debts. These policies were grounded in the contextual ideological components of economic independence and Pan-Africanism, whose interpretations were closer to the CPP administration’s intentions. This Acheampong-led NRC government, and later Supreme Military Council (SMC I) administration, was overthrown by an Edward Akuffo-led Supreme Military Council (SMC II) who, though they orchestrated a palace coup to overthrow Acheampong, did not deviate much from the previous administration’s pro-Nkrumah policies. Instead, they were more focused on restoring Ghana to multiparty elections. However, this administration lasted for only eleven months and was overthrown by a group of young militants, the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), who took power until after the 1979 elections and handed over to a democratically-elected People’s National Party (PNP). The PNP government, led by Dr Hilla Limann, was one of the latter attempts to bring introduce a full-fledged Nkrumaist party after the CPP was banned before the 1969 elections. Although to the disappointment of many Nkrumaists, this government did not pursue politics based on the ideas of Nkrumah’s CPP, its policies were somewhat closer to what the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group preferred—for instance, in attempting to the IMF for bailouts and broader pro-West economic relations. This was one of the reasons why the Rawlings-led military junta, now the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), returned to overthrow the PNP government in 1981. Although this group (PNDC) was generally touted as radical and anti-West, their internal ideological dynamics resembled the broader ideological dichotomy between the Nkrumah and Danquah-Busia-Dombo groups. Within the PNDC government was a group that aligned itself to Nkrumah’s CPP ideology and, for instance, were wary of the West, former colonial metropoles and programmes like the Structural Adjustment Policies. On the other side were those who were touted as less radical and ideologically closer to the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group, who were rather willing to engage the World Bank and IMF through the Structural Adjustment Programmes. This internal dialectic shaped the government’s domestic and foreign policy. However, from 1984, there seemed to be a broader consensus within the party as one whose ideology and politics was shaped by contextual structures, which made it difficult for the government to pursue policies just based on its internalised ideology. The PNDC later metamorphosed into the National Democratic Congress (NDC) when the government, under several domestic and international pressures, adopted multiparty democracy and elections from December 1992. After leading Ghana democratically for eight years, the NDC lost the December 2000 elections to the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Coming directly from the Danquah-Busia-Dombo tradition, the NPP government led by John Agyekum Kufuor pursued policies mainly in line with what the forerunners have proffered, especially against Nkrumah’s policies. For instance, they created an enabling environment for private property ownership and entrepreneurial development, including encouraging foreign investors, a strengthened relationship with the West, and for a greater emphasis on its economic and democratic values. To further the idea of Ghanaian personality that was based on respect for humanity and human rights, the government opened itself up for review by other African states through the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), and took steps to pursue regional integration from a functional economic perspective. From the discussions above, a few things must be clarified regarding Ghana’s ideological history. Socialism (for Nkrumaists) and classical liberalism (for the Danquah-Busia-Dombo group) have been the two dominant internalised macro-ideological leanings in Ghana, since independence. However, in an ever-changing, developing, and dynamic context like Ghana and the rest of Africa, these ideologies cannot function in their pure form, in their influence on policies. Therefore, in Ghana and Africa, I argue that context matters. Looking at the Ghanaian case teaches us three main things analytically about the African continent. First is the dominance macro-ideologies or the fact that we cannot ignore ideologies like liberalism, Marxism and socialism as they are usually primary to the ideological structure of many governments. Second is the power and relevance of contextual structures, like regional organisations and the Bretton Woods, to produce ideas that African governments take on or adjust to because of their putatively weaker position. Constructivists have long emphasised the learning function of states. Third is existence of historical conditions that have evolved into ideas over time. Chatterjee Miller’s study of India and China’s foreign policy reveals a longue durée ‘post-imperial ideology’, comprising a sense of victimisation and driven by the goal of recognition and empathy as a victim of the international system to maximise territorial sovereignty and status.[20] In the Ghanaian case, some of these conditions include economic independence, Africa consciousness and good neighbourliness. While these conditions pervade across different governments, the interpretations and approaches vary. Across the continent, these conditions of ideological value may vary, but they are very relevant to any analysis of ideology. This affords us the laxity to focus on ideological components, treating the macro-ideologies as part of the components. One of the reasons why ideology has been overlooked is the assumption that African states are weaker and have very little policy options because a lot of their policies are dictated by foreign powers. However, looking at ideology in itself is a bid to explore existing spaces, shed more light on those that have so far been neglected, and begin analyses of African politics from a perspective that acknowledges a certain contextual relevance and policy constraints. To do this, we should see ideologies as living variables that can interact with contexts to shape policies and the substance of the ideas themselves. Conclusion The place of ideology in global politics has been evolving in methodologies and vocabularies. This article is borne out of the bid to take Africa more seriously in that conversation by paying more attention to the contextualisation of ideas. This is not to say that ideologies explain everything, but it is to highlight the relationship between the interpretive value of ideology and contexts, and to emphasise that such relationships have a significant effect on African politics. The Ghanaian ideological context has been dominated by different shades of the Nkrumah and the Danquah-Busia-Dombo ideological dichotomy, characterised by an interaction between big-isms, contextual components and structures. These varieties of Ghanaian nationalism is bound to manifest differently in other African cases, but its conceptual proposition of interaction between context and ideas is very relevant. It demonstrates an understanding of African politics from within. Therefore, while this application gives us an indication and confidence to probe more into ideologies and policy-making in other African states, it also responds to the agency question which is fundamental to domestic and foreign policies. [1] Freeden, M. (2006). Ideology and Political Theory. Journal of Political Ideologies, 11(1), p. 19. [2] Bayart, J. F. (2000). Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion. African Affairs, 99, 217–267; Robertson, J., & East, M. A. (Eds.). (2005). Diplomacy and Developing Nations: Post-Cold War Foreign-Policy Structures and Processes. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [3] Brown, W., & Harman, S. (Eds.). (2013). African Agency in International Politics. Routledge Taylor & Francis. [4] Thompson, A. (2016). An Introduction to African Politics. In Routledge Handbook of African Politics (4th Edition). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p. 32. [5] Vijay Prashad (2021) What's the Left to Do in a World on Fire? | China and the Left. Public Lecture Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vd8w3ONjv6Y&t=453s Accessed 13th March 2022 [6] Ostrowski, M. S. (2022). Ideology Studies and Comparative Political Thought. Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), 1–10. [7] McCain, J. (1975). Ideology in Africa: Some Perceptual Types. African Studies Review, 18(1), 61–87; McCain, J. (1979). Perceptions of Socialism in Post-Socialist Ghana: An Experimental Analysis. African Studies Review, 22(3), p. 45. [8] Ibid, p. 46 [9] Gyampo, R. E. Van. (2012). The Youth and Political Ideology in Ghanaian Politics: The Case of the Fourth Republic. Africa Development, XXXVII(2), 137–165. [10] Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2012). Political Party Activism in Ghana: Factors Influencing the Decision of the Politically Active to Join a Political Party. Democratization, 19(4), 668–689. [11] Whitfield, L. (2009). “Change for a Better Ghana”: Party Competition, Institutionalisation and Alternation in Ghana’s 2008 Elections. African Affairs, 108(433), 621–641; Obeng-Odoom, F. (2013). The Nature of Ideology in Ghana’s 2012 Elections. Journal of African Elections, 12(2), 75–95 [12] Frempong, A. K. D. (2017). Elections in Ghana (1951-2016). In Ghana Elections Series (2nd Edition). Digibooks. [13] Potekhin, I. (1968). Pan-Africanism and the struggle of the Two Ideologies. Communist, p. 39. [14] Kwame Nkrumah: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 4th July, 1960, col. 19 [15] S. D. Dombo: Official Report of Ghana’s Parliament of 30th June 1960, col. 250 [16] Aluko, O. (1985). The Expulsion of Illegal Aliens from Nigeria: A Study in Nigeria’s Decision-Making. African Affairs, 84(337), 539–560. [17] Graphic Showbiz (21st May, 2020) Ghana Must Go: The ugly history of Africa’s most famous bag. Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/entertainment/features/ghana-must-go-the-ugly-history-of-africa-s-most-famous-bag.html#&ts=undefined Accessed 13th March 2022 [18] Although in 1954, when Nkrumah was the Prime Minister and three years before Ghana’s independence, some Nigerians were deported; but not on the scale, in terms of number and government’s involvement, of what happened in 1969. After independence, Nkrumah’s support for African immigrants and other African states seems to have overshadowed the 1954 deportation of Nigerians. [19] Ghana News Agency (28th September 2020) Ghana: 'Revive Nkrumah's Industries'. Retrieved from https://allafrica.com/stories/202009280728.html Accessed 13th March 2022 [20] Miller, C. M. (2013). Post-Imperial Ideology and Foreign Policy in India and China. Stanford University Press. by Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien

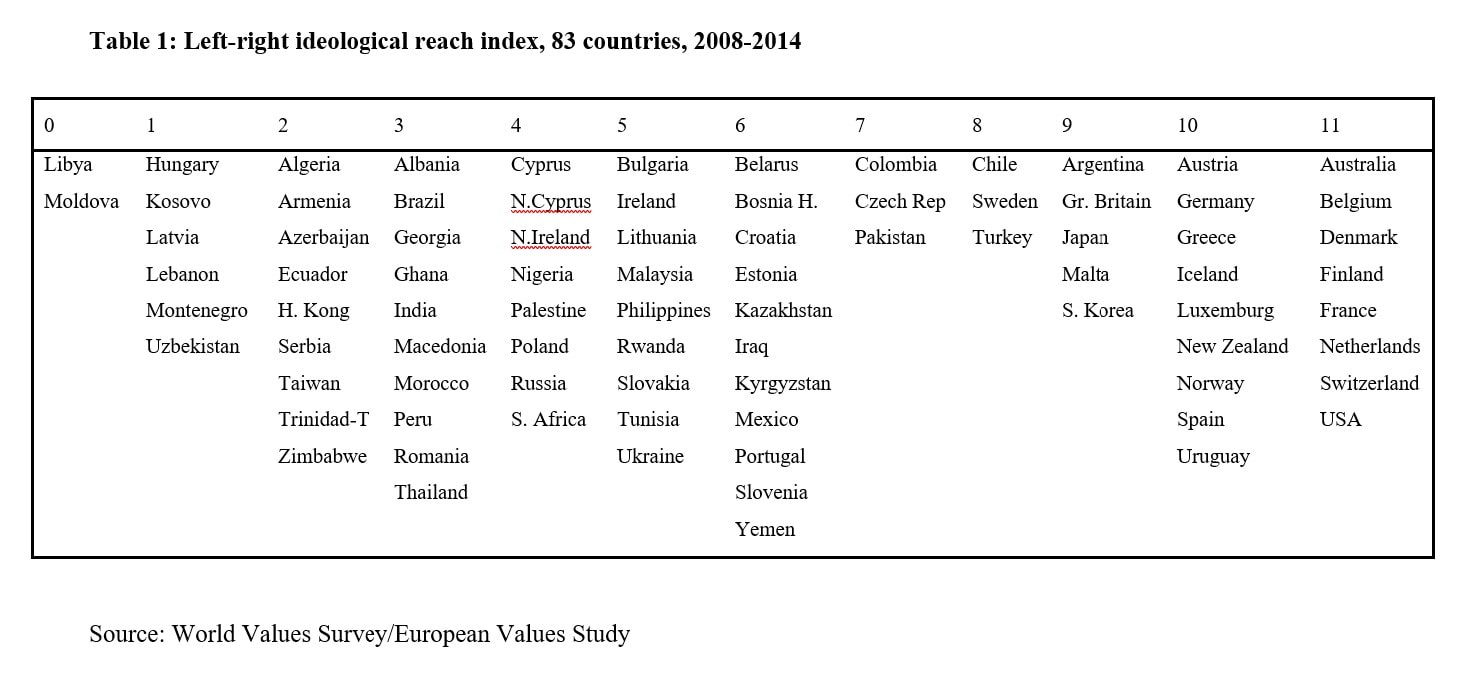

In recent years, several analysts have contended that the old cleavage between left and right has faded gradually, to become less central politically than it once was. The end of communism, the unchallenged victory of market capitalism, and the rise of neoliberalism narrowed the distance between parties of the left and of the right, and reduced the range of options available in political debates. Yet, although the left-right distinction may have become blunter as a cognitive instrument for politicians and voters, numerous studies show that it has not been replaced. In fact, no ideological cleavage is more encompassing and ubiquitous than the opposition between the left and the right.[1] When asked, most people across the world are able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, which basically divides those who support or oppose social change in the direction of greater equality. Ideological self-positioning also tends to be in line with the values and policy preferences associated with one of the two sides. The strength of this left-right schema, however, varies significantly among countries. In some cases, left-right positions correlate strongly with expected attitudes about equality, the state, the market, or social diversity; in others, they do not. We know little about the factors that make the left-right opposition more or less effective in structuring national debates. At best, existing studies suggest that left-right ideology is a more powerful constraint in Western democracies than elsewhere. To assess this question, we have taken the measure of cross-national variations in left-right ideology in 83 societies, and linked them to various factors, including economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy. Instead of focusing on individual determinants of ideology such as social class, gender or education, as scholars generally do, our analysis looks at country-level survey evidence and evaluates how, in each country, political debates are framed, or not framed, in left-right terms. The idea, along the lines suggested by Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, is to take the mass attitudes measured by large-N comparative survey projects as “stable attributes of given societies,” and as indicative of a country’s elites’ success in structuring politics along left-right dimensions. More specifically, we consider answers to twelve survey questions that capture the standard dimensions of the left-right political distinction. All answers were collected between 2008 and 2014 through the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS). The twelve questions include, for each society, one on individual left-right self-positioning, and eleven related to issues that have historically divided the two sides. The varying degree of ideological consistency in citizens’ responses then makes it possible to assess the architecture of a country's political debates and make cross-national comparisons. This approach to the workings of left-right ideology has two advantages. First, it moves the discussion of ideology beyond Western countries, and makes it possible to draw an extensive map of national ideological patterns. Second, and more importantly, because we use aggregate survey evidence, we can assess national-level causal mechanisms, and weigh, in particular, the respective influence of economic, social, and political factors on the constitution of the left-right cleavage. Our results indicate that the left-right opposition is unevenly effective in structuring national politics. Individual answers to questions about equality, personal responsibility, homosexuality, the army, churches, or major companies correlate with left-right self-positioning in more than half of the countries considered. But answers to questions about abortion, government ownership of industry, competition, trade unions, or environmental groups correlate with ideological self-positioning in only a third of the cases. In line with the expectations of Inglehart and Welzel, we also find that economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy are the best predictors of a structured left-right debate. Theorising left and right The construction of ideological identities is both a top-down and a bottom-up process, whereby people adopt political orientations defined by elites and institutions in line with their own personal predispositions. Psychologists have naturally paid more attention to the bottom-up, personal determinants of ideology, while political scientists have been more interested in the top-down, collective process. As a top-down process, the building of the left-right divide hinges on a country’s elites’ and institutions’ capacity to propose to voters what Paul Sniderman and John Bullock call a “menu of choices.” For these authors, political institutions—most notably parties—give consistency to the views of ordinary citizens, by providing coherent menus from which they can choose. As left-right self-positioning is strongly correlated with partisanship, we can hypothesise that a long-established, institutionalised party system contributes to structure ideological debates along left-right lines, compared to the more volatile politics of countries with fragile democracies. To evaluate if the “menu of choices” proposed by a country’s elites and parties and adopted by voters is organised along left and right lanes, we test whether divisions in a country’s public opinion appear consistent with individual left-right self-positioning. People on the left are likely to be more favourable to equality, state intervention, public ownership, and trade unions, and people on the right better disposed toward markets, individual incentives, competition, and major companies. The left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion and more supportive of environmental organisations, and the right more at ease with churches and the armed forces. In countries where the menu of choices is strongly structured by the left-right opposition, there should be significant relationships between individual left-right self-positioning and the expected attitudes on these questions; in countries with a less powerful left-right schema, these relationships should be weaker. Moreover, one should expect a connection between the structure of left-right discourse and the human development sequence identified by Inglehart and Welzel. Economic development, secularisation, and democratisation broaden the possibility, the willingness, and the rights of people to consider social alternatives. Economic development fosters the material capacity of a people to make choices, secularisation expands the moral frontiers of available choices, and democratic consolidation allows political parties and groups to define over time a menu of choices ordered around the usual left-right patterns. Left-right patterns should thus be associated with these three dimensions of human development. Methodology 83 societies have a complete set of WVS/EVS answers for the questions we select. The core question of interest concerns left-right self-positioning, and it is addressed by asking respondents to locate themselves on a 1 to 10 scale going from left to right. Although the rate of response varies significantly across countries, overall, about three-quarter of respondents proved able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, allowing for valid inferences about ideology. To verify whether this left-right positioning corresponds to consistent ideological stances, we correlate left-right positioning to responses on substantive political issues. Some of our eleven ideological questions refer to the core socio-economic components of the left-right cleavage (attitudes about equality, private or public ownership, the role of government, or competition), others concern cultural or social values (attitudes about homosexuality and abortion), and others tap respondents’ views about various organisations (churches, the armed forces, labor unions, major companies, and environmental organisations). We expect people on the left to be more favourable to equal incomes, public ownership of business or industry, and the government’s responsibility “to ensure that everyone is provided for,” and less likely to consider that “competition is good.” Respondents on the left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion, and more confident in labour unions and environmental organisations, but less so in the churches, the armed forces, and major companies. Using national responses to our eleven questions on substantive issues, we build a composite dependent variable, called left-right ideological reach. This variable measures the extent to which, in a given country, left-right self-positioning predicts the expected ideological stances on substantive political issues. If, in country A, the relationship between self-positioning and, say, attitudes about equality is significant (p < 0.05) and in the expected direction, we give a score of 1, and if not of 0. Adding results for eleven questions, a country’s score for left-right ideological reach can then range from 0, when self-positioning never correlates in the expected direction with a substantive left-right political division, to 11, when the expected relationships are present for all questions. To account for national differences in ideological reach, we use indicators for economic development, secularisation, and democratic experience, as well as a number of control variables, for cultural differences in particular. Results Left-right ideological reach varies significantly across countries, from 0 for Libya and Moldova to 11 for a number of Western countries, including France and the United States. As Table 1 shows, there are 27 countries with scores of 0 to 3, where left-right self-positioning hardly predicts respondents’ positions on traditional issues dividing the left and the right; 31 where left-right ideological reach is moderate, with scores of 4 to 7; and 25 where a person’s ideological self-positioning predicts her position on most issues, most of the time, with scores of 8 to 11. This is a new, multidimensional, and country-scale representation of left and right public attitudes across the world, and the idea of a relationship between left-right self-positioning and substantive political orientations appears validated, at least for nearly two thirds of our sample.

A cursory look at the data suggests, in line with the literature and with our theory, that left-right ideological reach is influenced by economic and democratic development. Countries with high scores in Table 1 are predominantly rich, established democracies; countries at the low end of the scale tend to be poorer, with authoritarian regimes or newer democracies. Indeed, economic development, measured by GDP per capita, is strongly correlated with ideological reach, and so are our indicators of secularisation and democracy. In multiple regressions, the three explanatory variables considered are significant, with democracy coming first. Control variables for cultural differences (religiosity and civilisations) are non-significant. These results are consistent with our interpretation of the left-right divide as a political construct that has global resonance but is clearly more structured in countries that have long experienced economic development, secularisation, and democratic politics. They also dispose of the seemingly common sense but misleading argument that would jump from a look at the cases in Table 1 to the conclusion that left and right are a Western specificity. Looking closely at the same table, one can see countries like Uruguay, Argentina, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Pakistan with scores of 7 or more, and countries like Hungary, Taiwan, and Brazil with low scores. Fostered by economic development and to some extent by secularisation, the left-right cleavage remains, first and foremost, a product of the enduring democratic conflict for control of the government. Not surprisingly, a host of comparative politics writings lend support to this conclusion, and suggests that the left-right divide is more structuring in countries with a strongly institutionalised party system. Conclusion The evidence from cross-national surveys is rather clear: around the world, most people are able and willing to locate themselves on a left-right scale and when they do, they tend to understand what this self-positioning implies. Their understanding, however, tends to be more comprehensive in countries that are more advanced economically, more secular, and more solidly democratic. As political parties compete for the popular vote, they construct an ideological pattern that makes sense for both elites and voters, and that gives structure to politics. When they fail to do so, or when democracy is non-existent, political discourse remains more haphazard, driven by context and personalities. To go beyond these conclusions, we would need to probe further the political mechanisms that contribute to the development of ideology. Looking systematically at the party system institutionalisation hypothesis, in particular, would seem promising. For now, however, we can be satisfied that the language of the left and the right seems to function as an imperfect but critical unifying element in global politics. [1] Russell J. Dalton, ‘Social Modernization and the End of Ideology Debate: Patterns of Ideological Polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7:1 (2006), pp. 1-22; John T. Jost, ‘The End of the End of Ideology’, American Psychologist, 61:7 (2006), pp. 651-670; Peter Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 206-222; Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien, Left and Right in Global Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); André Freire and Kats Kivistik, ‘Western and Non-Western Meanings of the Left-Right Divide across Four Continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18:2 (2013), pp. 171-199. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed