by Daniel Davison-Vecchione

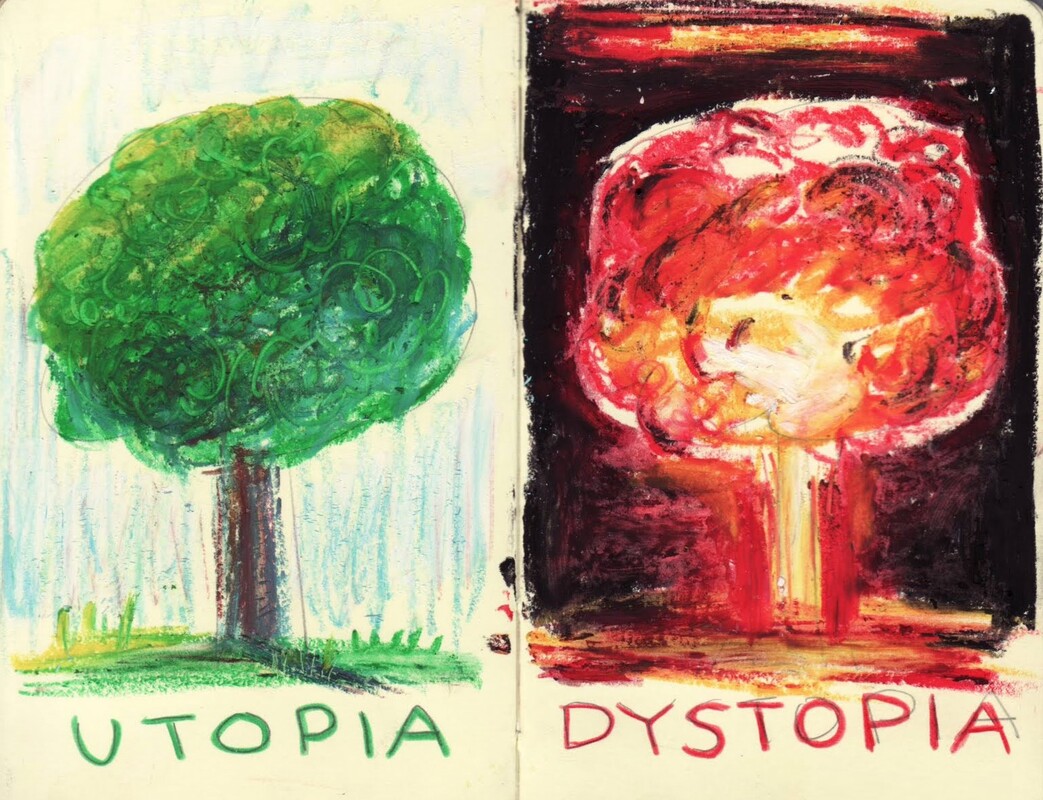

Social theorists are increasingly showing interest in the speculative—in the application of the imagination to the future. This hearkens back to H. G. Wells’ view that “the creation of Utopias—and their exhaustive criticism—is the proper and distinctive method of sociology”.[1] Like Wells, recent sociological thinkers believe that the kind of imagination on display in speculative literature valuably contributes to understanding and thinking critically about society. Ruth Levitas explicitly advocates a utopian approach to sociology: a provisional, reflexive, and dialogic method for exploring alternative possible futures that she terms the Imaginary Reconstitution of Society.[2] Similarly, Matt Dawson points to how social theorists like Émile Durkheim have long used the tools of sociology to critique and offer alternative visions of society.[3]

As these examples illustrate, this renewed social-theoretical interest in the speculative tends much more towards utopia than dystopia.[4] Unfortunately, this has meant an almost complete neglect of how dystopia can contribute to understanding and thinking critically about society. This neglect partly stems from how under-theorised dystopia is compared to utopia. Here I make the case for considering dystopia and social theory alongside each other.[5] In short, doing so helps illuminate (i) the kind of theorising about society that dystopian authors implicitly engage in and (ii) the kind of imagination implicitly at work in many classic texts of social theory. The characteristics and politics of dystopia A simple, initial definition of a dystopia might be an imaginative portrayal of a (very) bad place, as opposed to a utopia, which is an imaginative portrayal of a (very) good place. In Kingsley Amis’ oft-quoted words, dystopias draw “new maps of hell”.[6] Many leading theorists, including Krishan Kumar and Fredric Jameson, tend to conflate dystopia with anti-utopia.[7] It is true that numerous dystopias, such as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940), concern the horrifying consequences of attempted utopian schemes. However, not all dystopias are straightforwardly classifiable as anti-utopias. Take Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). The leaders of the patriarchal, theocratic Republic of Gilead present their regime as a utopia, which one might consider a kind of counter-utopia to what they see as the naïve and materialistic ideals of contemporary America, and at least some of these leaders sincerely believe in the set of values that the regime realises in part. One might therefore conclude that the novel is a warning that utopian thinking inevitably leads to and justifies oppressive practices. However, I would argue that The Handmaid’s Tale is not a critique of utopia as such, but rather of how actors with vested interests frame the actualisation of their ideologies as the attainment of utopia to discourage critical thinking. This reading is supported by how, for many members of Gilead’s ruling elite, the presentation of their society as a utopia is little more than self-serving rhetoric they use to brainwash the women they subjugate. Other dystopian works contain anti-utopian elements but subordinate these to the exploration of other themes. For instance, a subplot of Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan (2017) concerns a celebrity-turned-dictator’s dream of a technologically “improved” humanity, but resource wars, global warming, and other factors had already made the novel’s setting decidedly dystopian before this utopian scheme arose. Finally, there are major examples of dystopian literature, such as Octavia Butler’s Parable series (1993–1998), that depart from the anti-utopian template altogether. Tom Moylan has begun to rectify the dystopia/anti-utopia conflation via the concept of the critical dystopia. In his words, critical-dystopian texts “linger in the terrors of the present even as they exemplify what is needed to transform it”.[8] Put simply, critical dystopias are dystopias that retain a utopian impulse. Although this helps us understand many significant dystopian works, such as Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Gold Coast (1988) and Marge Piercey’s He, She and It (1991), the idea of the critical dystopia runs into its own problems. By labelling as “critical” only those dystopias that retain a utopian impulse, one makes it seem as if dystopia does not help us to understand and evaluate society in its own right—dystopia’s critical import becomes, so to speak, parasitic on utopia. To illustrate how this sells dystopia short, consider the extrapolative dystopia; that is, the kind of dystopia that identifies a current trend or process in society and then imaginatively extrapolates “to some conceivable, though not inevitable, future state of affairs”.[9] Many of Atwood’s novels fall into this subcategory. In her own words, The Year of the Flood (2009) is “fiction, but the general tendencies and many of the details in it are alarmingly close to fact”, and MaddAddam (2013) “does not include any technologies or biobeings that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory”.[10] These texts, which together with Oryx & Crake (2003) form Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, consider possible, wide-reaching changes that are rooted in present-day social and technological developments and raise pressing questions as to environmental degradation, reproduction and fertility, and the boundaries of humanity. Similarly, Butler constructs the dystopian future in her Parable series by extrapolating from familiar tendencies within American society, including racism, neoliberal capitalism, and religious fundamentalism. My point is not simply that these extrapolative dystopias are cautionary tales. It is that one cannot reduce their critical effect to either the negation or the retention of a utopian impulse. They identify certain empirically observable tendencies that have serious socio-political implications in the present and are liable to worsen over time. As such, they are critiques of present-day social phenomena and (more or less) plausible projections of how a given society might develop. The implicit message is that we can avoid the bad future in question through intervention in the present. This is how dystopia can translate into real-world political action. Taking perhaps the most famous twentieth century dystopia, in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) George Orwell was not simply satirising Stalin’s USSR or Hitler’s Germany. He was also considering the nature and prospects of the worldwide developments he associated with totalitarianism, including centralised but undemocratic economies that establish caste systems, “emotional nihilism”, and a total skepticism towards objective truth “because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuehrer”.[11] In Orwell’s words, “That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible”.[12] In the last couple of decades, dystopian texts have frequently sought to make similar points about global warming, digital surveillance, and the “new authoritarianisms”. One can certainly argue that taking dystopia too seriously as a means of critically understanding society risks sliding into a catastrophist outlook that emphasises averting worse outcomes rather than producing better ones. However, one should bear in mind that dystopia does not (and should not) aim to provide a comprehensive political program; rather, it provides a speculative frame one can use to consider current developments, thereby yielding intellectual resources for envisaging positive alternatives. The social theory in dystopia and the dystopia in social theory This brings us to the more direct affinities between dystopia and social theory. To begin with, protagonists in dystopian texts like Orwell’s Winston Smith, Atwood’s Offred, and Butler’s Lauren Olamina tend to be much more reflective and three-dimensional than their classical utopian counterparts. This is because, unlike the “tourist” style of narration common to utopias, dystopias tend to be narrated from the perspective of an inhabitant of the imagined society; someone whose subjectivity has been shaped by that society’s historical conditions, structural arrangements, and forms of life.[13] As Sean Seeger and I have argued, this makes dystopia a potent exercise in what the American sociologist C. Wright Mills termed “the sociological imagination”; that is, the quality of mind that “enables us to grasp [social] history and [personal] biography and the relations between the two”, thereby allowing us to see the intersection between “the personal troubles of milieu” and “the public issues of social structure”.[14] Since dystopian world-building takes seriously (i) how a future society might historically arise from existing, empirically observable tendencies, (ii) how that society might “hang together” in terms of its political, cultural, and economic arrangements, and (iii) how these historical and structural contexts might shape the inner lives and personal experiences of that society’s inhabitants, one can say that such world-building implicitly engages in social theorising. Conversely, the empirically observable tendencies from which dystopias commonly extrapolate, and the ethical, political, and anthropological-characterological questions dystopias frequently pose, are central to many classic texts of social theory. For instance, Max Weber saw his intellectual project as a cultural science concerned with “the fate of our times”.[15] He extrapolated from such related macrosocial tendencies as rationalisation and bureaucratisation to envisage modern humanity encased and constituted by a “shell as hard as steel” (“stahlhartes Gehäuse”) and feared that “no summer bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness”.[16] This would already place Weber’s social theory close to dystopia, but the resemblance becomes uncanny when one also considers Weber’s central interest in “the economic and social conditions of existence [Daseinsbendingungen]” that shape “the quality of human beings” and his related emphasis on the need to preserve human excellence and to avoid giving way to mere “satisfaction”.[17] This is a dystopian theme par excellence, as seen from such classics in the genre as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1951), which gives additional significance to the famous, Nietzsche-inspired moment at the end of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905). Here Weber wonders who might “live in that shell in the future”, including the ossified and self-important “last men”; those “specialists without spirit, hedonists without a heart” who “imagine they have attained a stage of humankind [Menschentum] never before reached”.[18] Like a good extrapolative-dystopian author, Weber provides a conceptually rich account of social phenomena by reflecting on what is currently happening and speculating about its further development and implications. It therefore seems that the dystopian imagination has always been at play within the sociological canon. While the extent of the overlap between dystopia and social theory is yet to be fully determined, much of this overlap no doubt stems from how central social subjectivity is to both endeavours. It is true that, in their representations of societies, dystopian authors as writers of fiction are not subject to the same demands of accuracy as social theorists. Nevertheless, the critical effect of much dystopian literature relies heavily on empirical connections with the world inhabited by the reader and, conversely, social theory often evaluates by speculating about the possible consequences of current tendencies. As such, one cannot consistently maintain a straightforward separation between the two enterprises. I am therefore confident that this nascent, interdisciplinary area of study will be productive and insightful for both social scientists and scholars of speculative literature. My thanks to Jade Hinchliffe, Sean Seeger, Sacha Marten, and Richard Elliott for their helpful comments on an early draft of this essay. [1] H. G. Wells, “The So-Called Science of Sociology,” Sociological Papers 3 (1907): 357–369, 167. [2] Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). [3] Matt Dawson, Social Theory for Alternative Societies (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016). [4] Zygmunt Bauman is a partial exception. See Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity, 2000 [1989]), 137; Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity, 2000), 26, 53–64; Zygmunt Bauman, Retrotopia (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), 1–12. [5] This essay raises and builds on points Sean Seeger and I have made in our ongoing collaborative research on speculative literature and social theory. See Sean Seeger and Daniel Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” Thesis Eleven 155, no. 1 (2019): 45-63. [6] Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1960). [7] Krishan Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times (London: Blackwell, 1987), viii; Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future (London: Verso, 2005), 198. [8] Tom Moylan, Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia (New York: Routledge), 198-199. [9] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 55. [10] Quoted in Gregory Claeys, Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 482. [11] Quoted in Kumar, Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times, 292-93. [12] Ibid. [13] This is complicated by the “critical utopias” that arose in the 1960s and 70s, which emphasise subjects and political agency much more than their classical antecedents. [14] Seeger and Davison-Vecchione, “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination,” 50; C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000 [1959]), 6, 8. [15] See, e.g., Lawrence A. Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage: Culture, Politics, and Modernity in the Thought of Max Weber (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1991); Wilhelm Hennis, Max Weber’s Central Question (Newbury: Threshold Press, 2000). [16] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trs. Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 121; Max Weber, “Politics as a Vocation,” in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, eds. H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005) 77-128, 128. “Iron cage” is Talcott Parsons’ mistranslation of “stahlhartes Gehäuse”. [17] Max Weber, “The National State and Economic Policy” (1895), quoted in Scaff, Fleeing the Iron Cage, 30. [18] Weber, Protestant Ethic, 121. 4/10/2021 Jean Grave, the First World War, and the memorialisation of anarchism: An interview with Constance Bantman, part 2Read Now by John-Erik Hansson

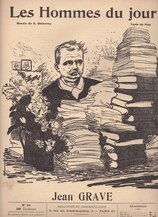

John-Erik Hansson: Let us now talk about the French and European contexts and turn to the First World War and to the relationship between anarchism and the French Third Republic. You discuss at length Jean Grave’s u-turn regarding the war and what leads him to draft and sign the Manifesto of the Sixteen, condemning him to oblivion, because he was one of the apostates—although other signatories like Kropotkin managed to remain in the good graces of a lot of people in the anarchist movement. There's an ongoing revision of our understanding of what exactly led to the split in the anarchist movement between the defencists, who were in favour of participating in the war, and those who simply opposed the First World War, exemplified by the recent edited collection Anarchism 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War.[1] For a long time being defencism was considered to be a betrayal of anarchist principles, but that view has changed over the last couple of years. What was Grave’s role in this debate? How does studying Grave help us rethink anarchism at that historical juncture?

Constance Bantman: The first thing to say is that the revision is very much an academic thing; that’s important to highlight when you talk about anarchism, which is of course a social movement with a very strong historical culture. The war will come up when you're talking to the activists who really know their history when you mention Grave. On France’s leading anarchist radio channel, Radio Libertaire, a few years ago, I heard him called a “social traître” [traitor to the cause]—I couldn't believe it! But within academic circles, the revision is underway and a great deal has come out: the volume that you mentioned and Ruth Kinna’s work on Kropotkin as well, all of which have been very important to revising this history. That’s courageous work as well, given all we’ve said about the enduringly sensitive nature of this discussion. Concerning Grave’s role in this, the first aspect to consider is the importance of daily interactions in people's lives. That’s an angle you get from a biography. So much has been said about Kropotkin’s own story and intellectual positions, and how this informed his stance during the war. Of course, that doesn't explain everything, especially if you look to the opponents to the war. Grave was initially really opposed to the war, his transition was really gradual but it was a U-turn, connected to his friendship with Kropotkin, who told him off quite fiercely for being opposed to the war. One thing we do see through Grave is this sense that some anarchists clearly predicted what would later be known revanchisme, the idea that there was so much militarism in French society that when the Entente won the war, there would be really brutal terms imposed on Germany, which would lead to another war. That’s something that Peter Ryley has written about in Anarchism 1914-18. Some anarchists were pretty lucid actually in their analysis and you do found traces of that in Grave. He really clearly understood the depth of the militarism of French society, and that's when he did a bit of a U-turn. He was also in Britain at the time, and didn't quite realise how difficult the situation was. He had left Les Temps Nouveaux and the paper was looked after by colleagues. They were receiving lots of letters from the front, from soldiers and, as has been analysed by other historians, this was crucial in the growth of an anti-war sentiment for them. They could see directly the horrors happening in the trenches, whereas Grave was immersed in upper-class British circles and had no clear sense of the brutality of the war. So, again, it's a mixture of ideas, ideology, and the contingencies of personal and activist lives when you try to assess positions that such complicated times. JEH: Again, this highlights the importance of personal connections in the formulation of political and ideological positions. While these positions might be influenced by personal connections, they then become rationalised into arguments that become part of the ideological vocabulary and the ideological fault lines in the movement itself… and that leads to the Manifesto of the Sixteen, in a sense. CB: Yes, absolutely that's very true. The manifesto was written as a document published initially in the press; it was not a placard. Arguments in favour of defencism as well as arguments by anti-war groups were published in the press in the form of letters meant to influence people. Grave once referred to the Manifesto of the Sixteen as the manifesto he wrote in 1917, whereas it had actually been written in 1916. This just shows that what is now regarded as this landmark document, this watershed moment in the history of Western anarchism was, for Grave, just one of the many articles that he had written. I think it took some time, maybe a decade or two, you can see that through Grave, for the Manifesto to be consolidated into the historical monument that it now is. Looking at this period through Grave brings out a degree of fluidity which is otherwise not apparent. JEH: This is very interesting point. In a way, anarchists built their own historical narrative and created a landmark out of something that was, as you mentioned, initially just another set of arguments between people who are connected and often knew one another personally. But this particular argument became much more important because of the way in which the anarchist movement memorialised itself. CB: Yes, absolutely and I think tracing it would be interested to trace how national historiographies and activist memories sort of converge to establish versions of history. In France, I would be really interested to see when exactly the Manifesto of the Sixteen congealed into this historic landmark. I wonder if it's Maitron and a mixture of activist circles and discussions. I haven't studied so much the period around the Second World War, but really, with activist memories in this period we may have a missing link here to understand the formation and how the 19th century was memorialised. JEH: From the First World War to the Third Republic, I would like to relate your book to a recent article by Danny Evans.[2] Evans argues that anarchism could or should be seen as “the movement and imaginary that opposed the national integration of working classes”. Grave is interesting in this respect because he becomes domesticated by the Third Republic. Would you say that anarchism and French republicanism are in a kind of dialectical relationship from 1870 until the Second World War, moving from hard-hitting repression to the domestication of a certain strand of anarchism seen as respectable or acceptable by French republicanism? CB: Now that's a very good point, and an important contribution by Danny Evans. Grave always had these links with progressive Republican figures and organisations like the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme, Freethinkers, academics etc.… One of his assets as well among his networks is his ability to get on with people, to mobilise them, for instance, in protest again repression in Spain and the Hispanic world. Many progressive figures were involved in that. And when Grave himself fell foul of the law during the highly repressive episode of 1892–94, many Republicans supported him, which suggests that a degree of republican integration was always latent for Grave. Then the war happened and he picked the right side from the Republicans’ perspective, and by then you're right, domestication is indeed a good term. I would also add that many of these Republicans considered that anarchism had been an important episode in the history of the young Third Republic, which might have made more favourably inclined towards it. Now if we look at domestication, Grave is an example of a sort of willing domestication, as you might say that perhaps he does age into conservative anarchism. But a classic example is that of Louise Michel. Sidonie Verhaeghe has just written a really interesting book about this[3], because if you think about Louise Michel having her entry into the Pantheon being discussed in recent years, she would be absolutely horrified at the suggestion. Having a square named after her at the foot of the Sacré Coeur, that’s almost trolling! But anarchism really reflects the history of the Third Republic from the early days, when the Republic was very unstable. You had the Boulangiste episode, and anarchism was perceived to be such a threat initially, until the strand represented by Grave ceases to be seen in that way. After the war, we enter the phase of memorialisation and reinterpretation; Michel and Grave represent two slightly different facets of that process. Regarding the point about the integration of the working classes, the flip side of Danny’s argument has often been used by historians—I'm thinking about Wayne Thorpe,[4] in particular—to explain why everything fell apart for French anarchists at the start of the First World War. The war just revealed how integrated the French working classes were, beyond the rhetoric of defiance they displayed. It's an argument you find to explain the lack of numerical strength of the CGT too. The working classes had integrated and the Republic had taken root, and Thorpe explains what happens with the First World War in the anarchist and syndicalist movements across Europe by looking at the prism of integration. That's a very fruitful way of looking at it. That's also great explanation because it encompasses so many different factors—economics, political control, and the rise of the big socialist parties which was of course crucial at the time. JEH: Actually, I was also thinking of the historical memory of socialists, as mass party socialism becomes dominant in the 20th century. In the late 19th century in the early 20th century when socialism was formulated, anarchism was an important part of that broad ideological conversation. But by the end of the First World War, from the socialists’ perspective, that debate is over. The socialists have won the ideological battle, and they are able to mobilise in a way that the anarchists aren't able to anymore. And at that point, the socialists can look back and try to bring anarchists into the fold, paying a form of respect to anarchism as an important part of socialist history. CB: Yes, I think there is probably an element of that, perhaps even an element of nostalgia. Many of these socialist leaders had dabbled with anarchism themselves before the war, so there is this dimension of personal experience and sometimes affinity. And it was still fairly recent history for them, I suppose, which plays out in a number of ways. There’s also the question of what happens with revolutionary ideas—for us the revolution is a fairly distant event, but for them the Commune was not such a distant memory. So, there is also this question of what do you do with a genuine revolutionary movement, like anarchism, and I think it was probably something they had to consider. [1] Ruth Kinna and Matthew S. Adams, eds., Anarchism, 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020); see also Matthew S. Adams, “Anarchism and the First World War,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, ed. Carl Levy and Matthew S. Adams (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_23. [2] https://abcwithdannyandjim.substack.com/p/anarchism-as-non-integration [3] Sidonie Verhaeghe, Vive Louise Michel! Célébrité et postérité d’une figure anarchiste (Vulaines sur Seine: Editions du Croquant, 2021). [4] Wayne Thorpe, “The European Syndicalists and the War, 1914-1918”, Contemporary European History 10(1) (2001), 1–24; J.-J. Becker and A. Kriegel, 1914: La Guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français (Paris: Armand Colin, 1964). |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed