by Tania Islas Weinstein and Agnes Mondragón

On July 1st, 2022, Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO) inaugurated the Dos Bocas oil refinery in his home state of Tabasco. The inauguration was a huge publicity coup for the president, who had promised to build the refinery when he first took office.

One of the highlights of the ceremony was the moment when the president unveiled—and fawned over—“La Aurora de México” (1947). La Aurora de Mexico [“The Dawn of Mexico”] is a painting depicting a woman embracing several oil towers as if these were her babies. La Aurora was painted by the late Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. It celebrates the expropriation of foreign oil companies and the nationalisation of the Mexican oil industry in 1938 by then-President Lazaro Cárdenas. Cárdenas appears at the top left of the painting together with Vicente Lombardo Toledano, a labour organiser who helped oil workers unionise. La Aurora harkens back to a product of an era in which the Mexican state actively supported artworks and monuments in public plazas, crossroads, and buildings around the country. That the authoritarian Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) was able to maintain a one-party rule for over seventy years (1929–2000) can, in part, be explained by its ability to tie its political achievements to those of the nation and ideologically interpellate the public into its political project through widespread political communication. The latter included supporting the production of artworks and monuments, many of which were was based on the idea of “art for the people” and, like La Aurora, are characterised by their “narrative style, realist aesthetic, populist iconography, and socialist politics”.[1] AMLO’s public celebration of La Aurora is noteworthy because the Mexican state’s support for the arts and its collaboration with artists has been waning for decades. This decline has accelerated in the wake of the country’s transition to a formal electoral democracy in 2000. Market-oriented reforms have enabled an unprecedented incursion of private corporations and collectors into the art world, who have increasingly supplanted the state as the arts’ main patron.[2] Despite AMLO’s declared opposition to the neoliberal turn in Mexican politics and his nationalist rhetoric that recalls the PRI era, this process has accelerated during his time in power. One of the most surprising characteristics of AMLO’s tenure has been his vocal disdain for artists and intellectuals. Rather than bringing artists back under the aegis of the state, the president has excluded them from his populist project by consistently accusing them of being members of a nebulous, neoliberal elite, and by cutting resources earmarked for artistic institutions as part of his fiscal policy of austeridad republicana or republican austerity.[3] In this context, the display of La Aurora de México during the Dos Bocas refinery’s inauguration is telling. Instead of commissioning a new artwork or monument for the new infrastructure, the government used an old painting that harkens back to the country’s post-Revolutionary authoritarian era and one that celebrates a key political accomplishment that has been framed by official history as a major act of anti-imperialist sovereignty. By displaying this painting at the inauguration, AMLO sought to signify a new era of assertive Mexican sovereignty and nostalgia for a time when Mexico’s economy grew rapidly through a politics of economic nationalisation. As he has argued repeatedly, the refinery will generate a “massive turn” (“un gran viraje”) back from the “neoliberal turn” of the 2000s and 2010s that had made Mexico dependent on imported petroleum.[4] In so doing, it will pave the way for the country to become more economically self-sufficient, which in turn suggests the return of an accompanying economic prosperity. The Aurora itself, meanwhile, is not actually publicly owned. Instead, it belongs to a private owner who loaned the piece to AMLO for the occasion. The Aurora will not remain at the refinery; the painting was returned to the owner as soon as the inauguration was over.[5] AMLO’s one-day exhibition of Siqueiros painting during the Dos Bocas inauguration is paradoxical. On the one hand, AMLO is using the Aurora to signify continuity with a past that is associated with the assertion of Mexican sovereignty and a state-driven economic policy, as a way to signal a break with neoliberal policy. On the other, the brevity of the display, and the fact that the artwork is privately owned also signifies the decline of the Mexican state’s support of public art and thus a continuity with the neoliberal turn rather than a break with it. But what if this interpretation is missing the point? What if rather than focusing on the Siqueiros’ painting as the refinery’s aesthetic and ideological locus we focused on the refinery itself? What if AMLO’s works of infrastructure—of which the Dos Bocas refinery is one among many—are the current administration’s monuments and works of art? Traditionally, monuments have been defined as interventions into the landscape that are built with the purpose of celebrating, commemorating, and glorifying a particular person or event and doing so by conveying a sense of permanence.[6] Extending J.L. Austin’s famous definition, Kaitlin Murphi argues that “monuments effectively function as speech acts: they are public proclamations of certain narratives that are intended to simultaneously reify that narrative and lay claim to the space in which the monument has been placed.”[7] In other words, Murphi maintains, in addition to conveying information, monuments also do things: they usher in or create a new state of affairs simply by laying claim to a space through their presence. While the Siqueiros painting cannot be said to have achieved this, given its impermanent presence, the refinery itself certainly did. Briefly framed by La Aurora, the refinery draws selectively from that celebrated past of oil nationalisation, thus operating like a monument. Indeed, works of infrastructure, much like monuments, possess a sign value that enables them to engage in similar meaning-making and political operations.[8] The Dos Bocas refinery instantiates the ways in which infrastructures may be attributed the symbolic power to effectively function as monuments. Monuments are “focal points of a complex dialogue between past and present,” connecting historical events that are worthy of monumentalisation and spectators who engage with the past via these objects.[9] The relationship that Dos Bocas establishes with that past and its glory is, crucially, mediated through the current political significance that this refinery is expected to have: it is not merely meant to be a repetition of the past, but rather another such moment of revolutionary change. This change, in the president’s words, is marked by a revival of the nationalised oil industry, which had been weakened by neoliberalisation, and thus a recovery of the nation’s lost dignity as a notable producer of oil. The refinery may then be mobilising the past of the Aurora towards its self-fashioning as part of an autonomous aesthetic-political project, making this infrastructure both a monument to the past and to itself. It is also, in many ways, a monument to an economic ideology that once proved to be quite fruitful and an attempt to revive the historical moment in which it did. However, when AMLO inaugurated the refinery, it was not yet ready to be used. Dos Bocas was rushed into being so as to mark a milestone of the current administration, but it was still at least a year away from beginning production. According to several news outlets, only the administrative part of the plant was ready, which represented 30% of the infrastructure. This was not lost on commentators, including prominent critical journalists who described the inauguration as a simulation, forcing AMLO to admit that the refinery was in fact just starting a trial period and would begin operations in earnest in 2023. In a sense, the incomplete—and, in a technical sense, useless—refinery merely constituted the staging of AMLO’s celebration of himself. By inaugurating it before it was finished, the president set the refinery in what Marrero-Guillamón calls a state of suspension, which is not “a temporary phase between the start of a project and its (successful) conclusion, but as a mode of existence in its own right.”[10] Without performing any technical function, the refinery’s power and meaning remain purely aesthetic and discursive, rendering it a monument. By being inaugurated in pieces, infrastructures may work as promises[11] and, therefore, as monuments to those who build them. For AMLO, this was not the first time he used Dos Bocas to stage a political event. On December 9, 2018, barely a week after his inauguration, AMLO laid the first stone at a massive event at the same site. This was marked by the attendance of several high-ranking politicians and a lengthy presidential speech that framed the refinery as part of an urgent solution to a profound crisis in Mexico’s oil industry, caused by waning investment in the state company, Pemex, and the failed effort to open the oil sector to private companies. This event circulated widely: its video was uploaded that same day to AMLO’s personal YouTube account, where it has been streamed over half a million times. The president has also frequently spoken about the refinery during his daily press conferences, showcasing other milestones in its construction, each time setting off discussions in the press and on social media. Following Isaac Marrero-Guillamón, we may see the materiality of Dos Bocas as “redistributed… into multiple instantiations other than its construction, such as exhibitions, technical documents, and public presentations.”[12] We can further extend this redistribution by considering how the extensive media coverage of these public events stretched the refinery’s visibility throughout the public sphere in its capacity as a monumental setting of presidential power. Indeed, a large part of the refinery’s public presence depends not on the concrete and steel of the infrastructure itself, but rather on the circulation of its representations. Given its remote location in a small coastal town in southwest Mexico, the refinery is only connected to most Mexican citizens in these highly indirect ways, much as the gasoline it will (eventually) produce will make its way through the pipelines and into the gas tanks of the vehicles transporting them. Like a monument, the meaning and experiences around Dos Bocas are produced in its abundant “verbal and textual sources.”[13] In official discourse, the refinery is meant to materialise the president’s project of soberanía energética, or energy sovereignty, which, in turn, points to a broader notion of sovereignty—that of an autonomous nation, no longer the object of its commercial partners’ imperial power. More than that, Dos Bocas is meant to be exemplary of the president’s political-economic project, dubbed the Fourth Transformation (4T). Though a precise definition of the 4T is lacking, the president usually invokes it “to describe a revindication of national pride, a political project of aligning the presidency with the popular will, and the creation of a social movement that could do away with the old party system, social inequality, and the economic status quo.”[14] It is meant to match the magnitude of three previous watershed moments in Mexican history: the Independence War (1810–1821), the Guerra de Reforma (Reform War, 1858–1861), and the Revolution (1910–1917). One could perhaps wonder whether the construction of a refinery can in fact be seen as revolutionary in an era of climate change, or whether it in fact constitutes an anticolonial, sovereign act. The refinery’s value rests less (if at all) in its technical function than in its performative capacity. Going back to Murphi’s definition of monuments, Dos Bocas, even in its unfinished stage, does things: it reifies the profound political transformation that AMLO claims to be spearheading and gives AMLO’s discourse concrete reality, thereby conjuring it into being. In so doing, the refinery ushers in a state of affairs that connects multiple temporalities. It draws on a glorified sovereign past and heroic struggle to shape a present that is rendered permanent through the infrastructure’s claim to space. In this scenario, artworks and monuments that celebrate AMLO’s political project are no longer needed, it is the infrastructure itself that does the work. The effectiveness of this infrastructure’s performative power vis-à-vis the old regime’s use of public art remains, however, an open question. To evaluate it, one may need to delve more deeply into the features of the ideological projects that each one is a part of and the conditions that have sustained them. These may include the actors involved in their orchestration and their aims; the distinct ways in which each project’s message has circulated—the former, for instance, privileging visual form in artistic representations of infrastructure, while the latter has resorted to discourse and spectacle; and the ways in which each has been taken up by those they are meant to address; as well as the possibilities for each message to be debated and challenged. But rather than thinking of these two projects separately, as competing endeavours, we must look at their mutual intertwinement as the source of their power. As we saw, La Aurora’s brief display at Dos Bocas’ inauguration meant to transfer its dense meaning to this infrastructure. The refinery’s symbolic force then hinged upon La Aurora’s own (historical) force, which AMLO sought to take in new directions. And, as he did so, he reaffirmed, perhaps reinvigorated, the force of an old, superseded medium, making it part of a new form of political communication. [1] Mary Coffey, How a revolutionary art became official culture (Durham: Duke University, 2012): 22. [2] Daniel Montero, El Cubo de Rubik. Arte Mexicano en los Años 90. (México, RM, 2014). [3] https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFAR_191119.pdf [4] Jon Martín Cullel. “López Obrador defiende la “autosuficiencia” en gasolinas en la inauguración de la refinería de Dos Bocas,” El País (July 1, 2022): https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-07-01/lopez-obrador-defiende-la-autosuficiencia-en-gasolinas-en-la-inauguracion-de-la-refineria-de-dos-bocas.html [5] Leticia Sánchez Medel. “Obra de Siqueiros es exhibida en la inauguración de la Refinería Dos Bocas,” Milenio (July 1, 2022): https://www.milenio.com/cultura/refineria-bocas-exponen-obra-siqueiros-inauguracion [6] James Young, The Texture of Memory (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993). [7] Kaitlin Murphy, “Fear and loathing in monuments: Rethinking the politics and practices of monumentality and monumentalisation,” Memory Studies 14 (6): 1143-1158. [8] Hannah Appel, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta, The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018) [9] Peter Carrier, Holocaust Monuments and National Memory Cultures in France and Germany since 1989 (New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2005, 7). [10] Isaac Marrero-Guillamón, “Monumental Suspension: Art, Infrastructure, and Eduardo Chillida’s Unbuilt Monument to Tolerance,” Social Analysis 64 (16): 28. [11] Appel, Anand, and Gupta 2018; and Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 327-343, 2013. [12] Marrero-Guillamón 2020, 28. [13] Carrier 2006, 22. [14] Humberto Beck, Carlos Bravo Regidor, and Patrick Iber, “Year One of AMLO’s Mexico,” Dissent (Winter 2020): https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/year-one-of-amlos-mexico by Mirko Palestrino

The study of social identities has been a key focus of political and social theory for decades. To date, Ernesto Laclau’s theory of social identities remains among the most influential in both fields[1]. Arguably, key to this success is the explanatory power that the theory holds in the context of populism, one of the most studied political phenomena of our time. Indeed, while admittedly complex, Laclau’s work retains the great advantage of providing a formal explanation for the emergence of populist subjects, therefore facilitating empirical categorisations of social subjectivities in terms of their ‘degree’ of populism.[2] Moreover, Laclau framed his theoretical set up as a study of the ontology of populism, less interested in the content of populist politics than in the logic or modality through which populist ideologies are played out. Unsurprisingly, then, Laclau’s work is now a landmark in populism studies, consistently cited in both empirical and theoretical explorations of populism across disciplines and theoretical traditions.[3]

On account of its focus on social subjectivities, Laclau’s theory is exceptionally suited to explaining how populist subjects emerge in the first place. However, when it comes to accounting for their popularity and overall political success, Laclau’s theoretical framework proves less helpful. In other words, his work does a great job in clarifying how—for instance—‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ came to being throughout the Brexit debate in the UK but falls short of formally explaining why both subjects suddenly became so popular and resonant among Britons. As I will show in the remainder of this piece, correcting this shortcoming entails expanding on the role that affect and temporality play within Laclau’s theoretical apparatus. Firstly, the political narratives articulating populist subjects are often fraught with explicitly emotional language designed to channel individuals’ desire for stable identities (or ontological security) towards that (populist) collective subject. Therefore, we can grasp the emotional resonance of populist subjects by identifying affectively laden signifiers in their identity narratives which elicit individual identifications with ‘the People’. Secondly, just like other social actors, populist subjects partake in the social construction of time--or the broader temporal flow within which identity narratives unfold. By looking at the temporal references (or timing indexicals) in their narratives, then, we can identify and trace additional mechanisms through which populist subjects tap into the emotional dispositions of individuals--for example by constructing a politically corrupt “past” from which the subject seeks to distance themselves. Laclau on Populism According to Laclau, the emergence of a populist subject unfolds in three steps. First, a series of social demands is articulated according to a logic of equivalence (as opposed to a logic of difference). Consider the Brexit example above. A hypothetical request for a change in communitarian migration policies, voiced through the available EU institutional setting, is, for Laclau, a social demand articulated through the logic of difference--one in which the EU authority would not have been disputed and the demand could have been met institutionally. Instead, the actual request to withdraw from the European legal framework tout-court, in order to deal autonomously with migration issues, reaggregated equivalentially with other demands, such as the ideas of diverting economic resources from the EU budget to instead address other national issues, or avoid abiding to the European Courts rulings.[4] It is this second, equivalential logic that represents, according to Laclau, the first precondition for the emergence of populism. Indeed, according to this logic, the real content of the social demand ceases to matter. Instead, what really matters is their non-fulfilment--the only key common denominator on the basis of which all social demands are brought together in what Laclau calls an equivalential chain. Second, an ‘internal frontier’ is erected separating the social space into two antagonistic fields: one, occupied by the institutional system which failed to meet these demands (usually named “the Establishment” or “the Elite”), and the other reclaimed by an unsatisfied ‘People’ (the populist subject). The former is the space of the enemy who has failed to fulfil the demands, while the latter that of those individuals who articulated those demands in the first place. What is key here, however, is the antagonisation of both spaces: in the Brexit example, the alleged impossibility to (a) manage migration policies autonomously, (b) re-direct economic resources from the EU budget to other issues, and (c) bypass the EU Court rulings, is precisely attributed to the European Union as a whole--a common enemy Leavers wish to ‘take back control’ from. Third, the populist subject is brought into being via a hegemonic move in which one of the demands in the equivalential chain starts to signify for all of them, inevitably losing some (if not all) of its content--e.g. ‘take back control’, irrespectively of the specific migration, economic, or legal issues it originated from. Importantly, the resulting signifier will be, as in Laclau’s famous notion, (tendentially) empty--that is, vague enough to allow for a variety of demands to come together only on the basis of their non-fulfilment, without needing to specify their content. In turn, the emptiness of the signifier allows for various rearticulations, explaining the reappropriations of signifiers between politically different movements. Again, an emblematic case in point exemplifying this process is the much-disputed idea of “the will of the people” that populated the Brexit debate. While much of the rhetorical success of the notion among the Leavers can be rightfully attributed to its inherent vagueness,[5] the “will of the people” was sufficiently ‘empty’ (or, undefined) as to be politically contested and, at times, even appropriated by Remainers to support their own claims.[6] Taken together, these three steps lead to an understanding of populism as a relative quality of discourse: a specific modality of articulating political practises. As a result, movements and ideologies can be classified as ‘less’ or ‘more’ populist depending on the prevalence of the logic of equivalence over the logic of difference in their articulation of social demands. Affect as a binding force While Laclau’s framework is not routed towards explaining the emotional resonance of populist identities, affect is already factored in in his work. Indeed, for Laclau, the hegemonic move leading to the creation of a populist subject in step three above is an act of ‘radical investment’ that is overwhelmingly affective. Here, the rationale is precisely that a specific demand suddenly starts to signify for an entire equivalential chain. As a result, there is no positive characteristic actually linking those demands together--no ‘natural’ common denominator that can signify for the whole chain. Instead, the equivalential chain is performatively brought into being on account of a negative feature: the lack of fulfilment of these demands. Without delving into the psychoanalytic grounding of this theoretical move, and at the risk of overly simplifying, this act of signification--or naming--can be thought of as akin to a “leap of faith” through which one element is taken to signify for a “fictitious” totality--a chain in which demands share nothing but the fact they have not been met. What, however, leads individuals to take this leap of faith? According to Ty Solomon, a theorist of International Relations interested in social identities, it is individuals’ quest for a stable identity that animates this investment.[7] While a steady identity like the one promised by ‘the People’ is only a fantasy, individuals--who desire ontological stability--are still viscerally “pulled” towards it. And the reverse of the medal, here, is that an identity narrative capable of articulating an appealing (i.e. ontologically secure)[8] collective self is also able to channel desire towards that subject. Our analyses of populism, then, can complimentarily explain the affective resonance--and political success thereof--of populist subjects by formally tracing the circulation of this desire by identifying affectively laden signifiers in the identity narratives articulating populist subjects. It is not by chance, for example, that ‘Leavers’ campaigning for Brexit repeatedly insisted on ideas such as ‘freedom’, or articulated ‘priorities’, ‘borders’, and ‘laws’ as objects to be owned by the British people.[9] In short, beyond suggesting that the investment bringing ‘the People’ into being is an affective one, a focus on affect sheds light on the ‘force’ or resonance of the investment. Analytically, this entails (a) theorising affect as ‘a form of capital… produced as an effect of its circulation’,[10] and (b) identifying emotionally charged signifiers orienting desire towards the populist subject. Sticking in and through time If affect is present in Laclau’s theoretical framework but not used to explain the rhetorical resonance of populist subjects, time and temporality do not appear in Laclau’s work at all. As social scientists working on time would put it, Laclau seems to subscribe to a Newtonian understanding of time as a background condition against which social life unfolds--that is, time is not given attention as an object of analysis. Subscribing instead to social constructionist accounts of time as process, I suggest devoting analytical attention to the temporal references (or timing indexicals) that populate the identity narratives articulating ‘the People’. In fact, following Andrew Hom[11], I conceive of time as processual--an ontology of temporality that is best grasped by thinking of time in the verbal form timing. On this account, time is but a relation of ordering between changing phenomena--one of which is used to measure the other(s). We time our quotidian actions using the numerical intervals of the clock. But we also time our own existence via autobiographical endeavours in which key events, phenomena, and identity traits are singled out and coordinated for the sake of producing an orderly recount of our Selves. Thinking along these lines, identity narratives--be they individual or collective--become yet another standard out of which time is produced.[12] Notably, when it comes to articulating collective identity narratives such as those of populist subjects, the socio-political implications of time are doubly relevant. Firstly, the narrative of the populist subject reverberates inwards--as autobiographical recounts of individuals take their identity commitments from collective subjects. Secondly, that same timing attempt reverberates also outwards, as it offers an account of (and therefore influences) the broader temporal flow they inhabit--for instance by collocating themselves within the ‘national biography’ of a country. Taking the temporal references found throughout populist identity narratives, then, we can identify complementary mechanisms through which the social is fractured in antagonistic camps, and desire channelled towards ‘the People’. Indeed, it is not rare for populist subjectivities to be construed as champions of a new present that seeks to break with an “old political order”--one in which a corrupt elite is conceived as pertaining to a past from which to move on. Take, for instance, the ‘Leavers’ campaign above. ‘Immigration’ to the UK is found to be ‘out of control’ and predicted to ‘continue’ in the same fashion--towards an even more catastrophic (imagined) ‘future’--unless Brexit happens, and that problem is confined to the past.[13] Overall, Laclau’s work remains a key reference to think about populism. Nevertheless, to understand why populist identities are able to ‘stick’ with individuals the way they do, we ought to complementarily take affect and time into account in our analyses. [1] B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), p. 31. [2] In this short piece I mainly draw on two of the most recent elaborations of Laclau’s work, namely E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005); and E. Laclau, ‘Populism: what’s in a name?’, in Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005) pp. 32–49. [3] See C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: an overview of the concept and the state of the art’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–24. [4] See Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [5] See J. O’Brien, ‘James O'Brien Rounds Up the Meaningless Brexit Slogans Used by Leave Campaigners’, LBC [Online], 18 November 2019. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/james-obrien/meaningless-brexit-slogans/ Accessed 30 June 2022. [6] See, for instace, W. Hobhouse, ‘Speech: The Will of The People Is Fake’, Wera Hobhouse MP for Bath [Online], 15 March 2019. Available at: https://www.werahobhouse.co.uk/speech_will_of_the_people. Accessed 30 June 2022. [7] T. Solomon, The Politics of Subjectivity in American Foreign Policy Discourses (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015). [8] See B. J. Steele, Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State (London: Routledge, 2008); and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [9] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. [10] S. Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), p.45. [11] A. R. Hom, ‘Timing is everything: toward a better understanding of time and international politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 62 (1) (2018), pp. 69–79; A. R. Hom, International Relations and the Problem of Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). [12] A. R. Hom and T. Solomon, ‘Timing, identity, and emotion in international relations’, in A. R. Hom, C. McIntosh, A. McKay and L. Stockdale (Eds) Time, Temporality and Global Politics (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2016), pp. 20–37; see also and T. Solomon, ‘Time and subjectivity in world politics’, International Studies Quarterly, 58 (4) (2014), pp. 671–681. [13] Why Vote Leave? What would happen…, Vote Leave Take Control Website 2016. Available at http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html. Accessed 30 June 2022. 30/5/2022 Culture and nationalism: Rethinking social movements, community, and free speech in universitiesRead Now by Carlus Hudson

Although the study of social movements has shown that state institutions are not the only vehicles for societal change, the political forces which emanate from civil society and challenge state authority require theorisation. Near the end of his life, in 1967 Theodor Adorno conceptualised the post-1945 far right as a potent movement with social and cultural attitudes spread widely in West German society and still capable of attracting mass political support.[1] Nazism’s defeat in 1945, the partitioning of Germany and the process and legacy of denazification kept the re-emergence of a similar threat at bay, but the ideology did not disappear. By rejecting a monocausal social-psychological explanation of post-war fascism, Adorno also rejects the pessimistic idea of it as something that people must accept as an inevitable part of living in modern and democratic societies.

Anti-fascists have the agency to change society for the better and they have used it for as long as fascism has existed. Fascist street movements in the UK were defeated in the 1930s and again in 1970s by anti-fascists who mobilised against them in larger numbers at counter-demonstrations. Students took anti-fascism into the National Union of Students (NUS) by voting for the ‘no platform’ policy at the April 1974 conference. The aim of the policy, which built on earlier anti-fascist praxis and has returned in different forms since then, is to deny spaces in student unions to the ideas espoused by fascists and racists, thereby making them less mainstream and limiting the size of the audience reachable by fascist and racist ideologues. By no platforming, students were able to use their unions instrumentally to counter the influence of the extreme right. They were driven by moral revulsion at fascism and racism, a near-universal positive commitment to democratic freedom in society, and in smaller numbers commitments to anti-fascism and anti-racism as social movements and to left-wing politics. The same tactics were later used against homophobic, sexist, and transphobic speakers. Evan Smith’s critically acclaimed study of ‘no platform’ historicises the tactic’s use in the contexts of anti-fascism in Britain and contemporary fear on the right, which he argues is unfounded, for free speech on campuses.[2] Three essential points can be made from Smith’s study about what ‘no platform’ is. Firstly, it is a political decision made against a particular person or group of people. Secondly, those decisions rely on the judgement of the validity of specific demands for restrictions on free speech. Thirdly, ‘no platform’ is a specific type of restriction on free speech that is set apart from the functionally synchronous restrictions put in place by national governments. Governments have legislated limitations on free speech and protections on citizens’ rights to express it in a variety of ways. Free speech is not immutable because political dissidents occupy a contradictory space that leaves them permanently open as targets of state repression and targets of co-optation in the repression of the other. Marxist and anarchist theorists of fascism before 1945 conceptualised it in similar terms to their analyses of states, societies and ideologies: historical formations driven by class interests.[3] As a researcher of student activism, I notice how little can be found in their perspectives about student unions compared to united and popular fronts, revolutionary unions, and vanguard parties. Students’ involvement in political activities and adherence to different ideologies is well-documented. It suggests that student unions affiliated to universities remained peripheral in the organising activities and theoretical interventions of the interwar left. Meanwhile, the growth of free speech as a talking point for the right is unexpected judging by the norm in European and North American history, because of the state repression and censorship that accompanied reaction to political revolutions from the seventeenth to the late twentieth century.[4] While there is no reason to imagine this as any different from state repression outside of European and North American contexts, this chronology can be extended into the twenty-first century with consideration of the rise of new authoritarian governments in Poland, Hungary and Russia.[5] In the twentieth century the British government put limits on the freedom of speech to espouse extreme and hateful views using the Public Order Act 1936 and the Race Relations Acts passed in 1965, 1968 and 1975, but as Copsey and Ramamurthy have shown it has been anti-fascist and anti-racist movements rather than government legislation that has most to counter fascism and racism.[6] In the late 1960s and 1970s, when the National Front (UK) was at the height of its popularity posed a danger with the possibility of winning seats in local elections, it turned its hatred on Black and Asian immigrants under a thin veneer of populist opposition to immigration and criminality. It added Black and Asian people to Nazism’s older enemies—Jews, communists, the Romani, and LGBT people—while it kept its ideological core out of public view.[7] The brief and limited success of the National Front (UK) can be read patriotically as an aberration or an anomaly in a society that was utterly hostile and inhospitable to it. In this view, civil society would eventually have defeated the National Front without the help of anti-fascists or any compromise on free speech at universities. One problem with that interpretation is the racialisation of religious communities after the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the initiation of the War on Terror. Anti-Zionism, the broad-brush term for opposition to Israel, includes anything from criticism of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians on human rights grounds to opposition to Israel’s existence as a country. Left-wing anti-Zionism has received more attention in research about student activism than the anti-Zionism of the extreme right. NUS leaders opposed left-wing anti-Zionist uses of ‘no platform’ in the 1970s, when it was introduced to student unions.[8] After the September 11 attacks, anti-Zionism drew renewed criticism but with greater emphasis on Islamism. Pierre-Andre Taguieff explained the growth of a new type of European anti-Semitism in those terms.[9] In the popular press, a debate about Islamism spilled over into Islamophobic racism. For example, the printing in Charlie Hebdo and Jyllands-Posten of the Mohammed cartoons were acts of mainstreaming Islamophobia in France and Denmark that supported moral panic about Islam. The attack in France on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 had a chilling effect on free speech by contributing to a political climate where it became impossible for ‘those who felt unfairly targeted’ to respond and be heard.[10] Understanding the problem of Muslims being shut out of debates about them, and of being transformed into a debateable question in the first place, requires a consideration of counter-terrorism measures that have marginalised Muslims. In England and Wales, the regulation of charities and the government’s Prevent duty which covers the whole of the UK have added such pressures to the free speech of Muslim students and workers at universities.[11] The positioning of the presence of Muslims in majority White and Christian countries by non-Muslims as a question of cultural compatibility instead of Islamophobia as a racism morally equivalent to anti-Semitism makes it harder for multiculturalism to function there. That said, explanations of the racialisation of religious minorities are incoherent without analysing race. The number of examples that could be given to prove why restrictions on freedom of speech are too harsh in some instances but not harsh enough in others are practically without limit. Anti-fascists who also consider themselves to be communists or anarchists support the administration of justice in ways that are radically different from those in our own societies but which are nonetheless constructed on the same principles that adherents of liberal democracy follow, including freedom of speech. The same statement descends into nakedly racist prejudice when it is used to refer to racialised religious communities. Free speech is at the centre of a cultural conflict. The first two decades of the twenty-first century saw a world economic crisis and the growth of populism and authoritarianism on the right, which according to Francis Fukuyama capitalised on the need for social recognition felt by resentful supporters. As economic inequality grew, identity politics showed an alternative way for people to articulate difference.[12] Identity politics itself changed little through these processes. For example, a prevailing idea among American conservatives is that universities and colleges, like other levels of the education system and other sectors of civil society, are dominated by a left that threats freedom of speech. Dennis Prager sets the stage for a battle for liberal opinion between the left and, he argues, the centre’s natural allies on the conservative right.[13] His views about universities should not be decontextualised from his commentary on religion. In his book written with Joseph Telushkin, Prager explains anti-Semitism using a history of it and an engagement with Jewish identity. They acknowledge the influence of Taguieff’s research on their taking anti-Semitism more seriously as a tangible threat to Jews. Opposing Anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, which they barely distinguish, is a key part of their argument.[14] From another perspective, in his defence of classical liberalism, Fukuyama dedicates a chapter to discussing the global challenges in the twenty-first century to the principle of protecting freedom of speech. One argument he makes is that critical theory and identity politics, when they appear together in the contexts of free speech in higher education and the arts, mistakenly give too much importance to language as an interpersonal mode of political power and structural violence instead of the main targets of leftist critique: the coercive function of institutions and physical violence, capitalism and the state. With universities engaging with a wider definition of what constitutes harm than they have in the past, the parameters for unacceptable speech have widened too.[15] Free speech is no less a political issue today, by which I mean it is a term that people use to express their ideological attachments and experiences of real socio-economic conditions, than it has been in the past. Different conclusions can be drawn from these points. One option is to join socialists and progressives in their fights for equality and social justice through a movement that simultaneously counters the hegemony of right-wing ideology. Another option is to join the right’s defence of freedom of speech on campuses against ‘woke’ students and academics, ‘safer spaces’ and ‘trigger warnings’. Far from simply being bugbears, they are central concepts of opposition for the right in their wider defence of what they value most in their idea of Western civilisation. A more analytical response would be to engage more critically with what identity politics is and engage with the probing questions of how social movements driven by identity politics affect the inclusiveness of societies. Religious, secular and post-secular nationalisms are relevant here because they have a greater determining role than economic interest on political beliefs constructed around identity. However, their influence on politics organised along a left-right axis has never been negligible and the claim that a purely economistic political ideology can exist is highly dubious. Understanding identity politics gives context to the right’s fear for freedom of speech. Another approach is to take the right’s claim at face value and begin to think of freedom of speech as a legislated guarantee for the conditions of voluntary social interaction, without which civil society becomes an impossibility. It would therefore be morally necessary to consider the figuration of the right’s semi-invented enemies. The presentation of these enemies is not necessarily a racist act of subjective violence, and this caveat demarcates a large section of the right from fascists and identifies them as fascism’s serious competitors. At the same time, the right delegitimises its opponents by tarring them as enemies of freedom of speech and therefore a step closer to fascism. What these examples show is how complex an issue freedom of speech at universities is. Freedom of speech must be defined in recognition of that complexity because we are at the greatest risk of losing this freedom when we express ourselves under assumptions that lead us to oversimplify and decontextualise it. [1] Theodor W. Adorno, Aspects of the New Right-Wing Extremism, trans. Wieland Hoban (Medford: Polity, 2020). [2] Evan Smith, No Platform: A History of Anti-Fascism, Universities and the Limits of Free Speech, (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2020). [3] Dave Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, new and updated edition (London: Pluto Press, 2020). [4] Dave Renton, No Free Speech for Fascists: Exploring ‘No Platform’ in History, Law and Politics (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021), 11-34. [5] Dave Renton, The New Authoritarians: Convergence on the Right (London: Pluto Press, 2019). [6] Nigel Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain, second edition (London; New York: Routledge, 2017), 56; Anandi Ramamurthy, Black Star: Britain’s Asian Youth Movements (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 25. [7] Dave Renton, Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League 1976-1982 (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2019), 14-36. [8] Dave Rich, The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism (London: Biteback Publishing, 2016). [9] Pierre-André Taguieff, Rising from the Muck: The New Anti-Semitism in Europe (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2004). [10] Aurelien Mondon and Aaron Winter, Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020), 75-9. [11] Alison Scott-Baumann and Simon Perfect, Freedom of Speech in Universities: Islam, Charities and Counter-Terrorism (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021). [12] Francis Fukuyama, Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition (London: Profile Books, 2018). [13] Jordan B. Peterson, No Safe Spaces? | Prager and Carolla | The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast - S4: E44, YouTube, vol. S4: E44, The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHXxtyUVTGU. [14] Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin, Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism, the Most Accurate Predictor of Human Evil (New York: Touchstone, 2007). [15] Francis Fukuyama, Liberalism and Its Discontents (London: Profile Books, 2022). by Aline Bertolin

‘There must be some kind of way out of here, said the joker to the thief’.[1] Except there isn’t. We all know it; some have known for longer. We stand bewildered before the cusp of a new world once promised to us fading away at the horizon. A world that may be within reach elsewhere, who knows; a unified world some minds and hearts glimpsed, and that perchance still hides in an Einsteinian fifth dimension amidst a warren of other hatching modern truths that we are still striving to decipher and from whose weight we can get no relief. And the thieves, and the jokers, and all the other outcasts seem to have the upper hand in this state of ideological affairs because they have known since jadis that there is no rest for the wicked: the game is rigged, and it has always been. It might be time we listen to them.

Truth and certainty Science is certainly not answering the paramount questions on this quantic leap we have failed to take. It has become too deeply entrenched in the current ‘nice v. nasty Twitter game’[2] and its ‘hermetically self-contained, self-referential certainty’.[3] Meanwhile, the portal to that dimension of global solidarity—where supranational and international institutions united would enhance development throughout the globe, development that we are all geared up for—is closing. The inheritance of this quest remains with us, nonetheless: the neuroplasticity and semantics created by the language of snaps and ‘snirks’[4] of the noosphere, carved by the ‘anxieties of the global’,[5] led us to fear, numbness, and exhaustion, a direction diametrically opposed to the ‘spirit of solidarity (Solidaritätsgeist) promised by globalism; their ways certainly have not spared Science either. Au contraire, it has plastered it together with all our gnoseological senses, which would have caused Popper’s dismay,[6] and curbed it in a much harder shell than the one envisaged by Max Weber[7]—a shell of virtue-signalling and fear. And that fear disconnected us from each other, and that shell became the equivalent of a platonic cave of over-assumptions. Hiding in our certainties only made us feel even more acutely the ‘solostalgic’[8] effects of both. If self-absorption and overreaching are what is holding us back from taking that leap, the supplicant question, borrowing the term from coding, is: how did it start, so how can we end it? Reading the works of fellow social scientists about European ideology being tantamount to the book of revelation of exclusion, an analogy emerges with some neo-Durkheimian tools that are lent powerful new sophistication by Elizabeth Hinton’s ‘social grievances theory’.[9] The effervescent ideas on how, from Europe to the globe, the Judeo-Christian morality—not tradition, for terminology’s sake[10]—is the proto-code deeply rooted into the code of law and ethos by which we live, which thus must answer for the ‘unweaving’ of people from the fabric of contemporary society, could be neatly tied together with some of the causes in Hinton’s depiction of what lit ‘America on Fire’.[11] It gives us the sense, though—and history has seemed to agree—that religious affiliations were rather a pitiful root cause. While the effects of the ‘discovery doctrine’ are well-documented and deeply-felt by many hearts across the globe,[12] so too is the scapegoatism of blaming religion for historical upheavals. Gender bias, labour un-dignification, racial hierarchisation knotted by a rating of intellectual capital to ethnicities, among the vast spectrum of pain as we now know inflicted on humans by debasing individuals and populations for what they hold dearest in their existential core, seem to be a modus operandi esquisé by Europe. A carrefour of civilisations, as many other geopolitical spaces were from age to age, Europe misappropriated ideas plentifully, and it certainly cannot be denied the position of the epicentre of postmodern ideological mayhem;[13] rather it seemed to have ‘nailed it’—since it was ‘Europeans’ who crucified the Jewish Messiah, and who disenfranchised him and his disciples from their beliefs of communion and universality, putting in motion the whole shebang of religious morale to be spread around the globe, in the same way as one has to admit that Islam started as a countermovement to save Europeans from doing precisely this, just to become their next disenfranchising target. Approaching Eurocentrism to this end in Social Sciences’ turf, was, therefore, nerve-wrenching. In contemporaneity, all scientific fields seem to share the sense of being cloistered by Science’s own gregarious endogenies, taunted by the reality of postmodern global pain. This is because scientific results stem from the same source of common cravings for logic,[14] cleaved only by the appeal such results may have to peer-reviewing and method; as society now stands, their gratification has been dangling on a fickle flow of likes and shares as much as any other gnoseological reasoning. Thus, unsurprisingly, the closing of the portal to the realm of necessary ideological epiphanies laced by humanism has received a more lucid treatment from fantasy and fiction, in other words, from Art. ‘Art and epistemology’ makes for an enticing debate, but remaining with the aspect of art being the disavowed voice in logic’s family midst, cast out by epistemological puritanism—like the daughter in Redgrave’s painting, ‘The Outcast’—is just enough to bring ourselves to see its legitimacy in leading the way towards unspeakable truths. In the adaption of Isaac Asimov’s masterpiece, Foundation, Brother Day says ‘art is politics’ sweeter tongue’[15]—but it can also be, and it often is, ‘tangy’. In the comfort of our successful publications and titles, we gave in to the idea of abdicating the freedom to speak about the truth as an essential step into Socratic academic maturity. How truth has become an intangible notion in the mainstream of the social sciences and a perilous move in the material world of politics—as Duncan Trussel so trippily, yet pristinely, described in Midnight Gospel[16]—is another story. To the outcasts making sense of contemporary times through art, nevertheless, this comfort was not agreed-upon; even less so, and principally, among the economic and societal outcasts stripped from their dignity. Living at the sharp end of this knife, they had to muster wisdom with every small disaster,[17] and, with hearts of glass and minds of stone torn to pieces, face what lay ahead skin to bone;[18] and then to fall, and to crawl, and to break, and to take what they got, and to turn it into honesty.[19] Science as it stands, relying on applauses, can hardly tap into this ‘real-world’; whereas Popperian truth and critical reasoning are in short supply. Mustering the voices from the field and presenting them to our fragile certainties and numbed senses has been the work of Art. Eurotribalism, Americanism, and Globalism In ‘How we kill each other’, a team of data scientists looking into the US Federal Bureau of Investigation succeed in clustering profiles of murder victims across all the states with the aim of discerning more information about the relevant perpetrators. They explored a data set from the FBI Murder Accountability Project, identifying trends in a thirty-five-year period (1980–2014) of murders, looking to build a predictive model of the murderer’s identity based on its correlations to victims’ traits—age, gender, race, and ethnicity—and murder scenes. Grouping victims’ profiles could prove to be useful in identifying, in turn, a murderer’s type for victims[20]. While facing difficulties in achieving this goal, the research results were insightful in confirming some typical depictions of crimes in the US—the mean murder in the prepared data set is a thirty-year-old black male killing a thirty-year-old black male in Los Angeles in 1993, using a handgun—but also revealing different clusters of perpetrators tied to uncalled-for-methods of murder, for instance, women’s prevalent use of personal methods, involving drug overdoses, drowning, suffocation, and fire, going against the expectation of females ‘killing at distance’. The spawn of novelty introduced by this research seemed to have less to do with ‘how’ Americans kill, but ‘how consistently’ Americans kill within certain groups, i.e., in proximity. In all clustered groups, crime seemed to be the result of an outburst against extenuating circumstances specific to that type of crime. And, though a disreputable fact, it is also one of rather universal than domestic interest. The social grievances in American society studied by Hinton can be pointed to as causes of this consistency in ‘proximity violence’. They have been, moreover, better approached by Art than Science during our unbreathable times. Art has certainly done a better job of giving us hints about the roots of the evil of contemporary violence. Looking at the belt of marginalised people around society, Art has been trying to tell us to grieve together, appealing to our senses and the universality of pain. It has moreover educated us on the remittance of public outcry for the protection of fundamental rights in the history of the US. How guns have been used unswervingly and in deadly ways in this peripheric belt that surrounds the nucleus of entitlement, and in ways that those communities victimise themselves rather than any other group, speaks volumes about ideological global dominance, where the echoes of past Eurocentric ideology can still be heard. Sapped of all energy and aghast of being praised for their ‘resilience’, the African descendants’ forbearance from acting against unswerving European subjugation was counterbalanced by cultural resistance. It made the continent richer beyond the economical sense, i.e., in flavours and sounds and art that benefited greatly and continuously not only the Americans lato sensu—remembering how the roots of slavery are intertwined with the southern countries of the continent—but Europe as well. Currently, it is not surprising that the advocacy for gun control rises from the population that had suffered by and large from being armed in the peripheries of the US, whereas those entitled to protection inside the belt cannot relate to the danger guns represent. Guns are made to protect their entitlement after all, and the system works, directly or indirectly, as guns are mainly used by outcasts to kill outcasts. The question lying beneath these grounds is how strong the mechanics of exclusion and violence crafted by Europeans centuries ago is still operating and entrapping us in cyclic violence, despite our best efforts as scientists, social engineers, and legal designers suffering together its outcomes. A scene from ‘Blackish’ where a number of African Americans refrain from helping a white baby girl lost in the elevator[21] may explain something about the torque of these mechanics. For generations, black men in the Americas were taught not to dare to look, much less to touch, white girls, and changing their disposition on it is not an easy task, and for most, an objectionable one—anyone who sees the scene played so brilliantly with the blushes of comedy will not suspect the punch in the stomach that accompanies it, as the spectator cannot escape its actuality. ‘The Green Mile’ goes deeper into the weeds to explain this. When we confront, on the one hand, the reality of Andre Johnson (Anthony Anderson) in ‘Blackish’, as taught by his ‘pops’ (Lawrence Fishburne), with, on another hand, Ted Lasso’s loveable character Sam Obisanya (Toheeb Jimoh), who is also very close to his father (uncredited in the show), but comes from Nigeria to England, concerning white women, another important point comes out to elucidate the differences on both sides of the Atlantic in how Africans and African descendants interact with gender and race combined. Andre is taught about the ‘swag’ of black males and how to refrain from wasting it on white women; whereas Sam is highly supported by all around him as the love interest of the most empowered female character in the show, Rebecca Walton (Hannah Waddingham), and winds a loving delicate sway over his peers and all over the narrative due to his affable nature. Africans and unrooted African descendants experience differently this combination of gender and race, accrued by geography, since it matters which sides of the Atlantic they may be on. These few examples add shades and textures to the epitomic dialogue between T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) and Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) in the final scenes of ‘Black Panther’, on what could be seen as the consequences of what Europe did to the globe by forcefully uprooting Africans from their natal homes. Misogyny, Eugenics, and Radical Ecologism Like in Redgrave’s painting-within-the-painting—where the dubiousness of the biblical story depicted in the picture in the wall, either of Abraham and Hagar and Ishmael or of Christ and the Adulterer, is purposedly ‘left hanging’ in juxtaposition to the paterfamilias power justification to the father to curse his progeny out of his respectable foyer—religion in Europe remains fickle towards the real problem, which has always been the persistent European ways of weaponising ideologies. The farcical blame on Christianity to justify Eurotribalism has in this light been a growing distraction among social scholars. That Judeo-Christian morality—not tradition, since this idea of an ensemble tradition was antisemitic in its base—has revamped or revived in itself in many echelons, including neo-Nazi ecologism—which certainly is astonishing—should not be concerning in itself: it is the 101 of Kant on moral and ethos. This new ‘bashing’ of religion is another form of European denial, a refusal to take responsibility for its utilisation just like any other ideology Europe has used to justify violence. European tribalism and the game-of-I-shall-pile-up-more-than-my-cousin that Europeans have been playing for centuries answers better for the global roots of evil sprawl through self-righteousness dominance. It crossed the Atlantic and remained in play. The Atlantic may be a shorter distance to cross, though, in comparison with the extent of the abyssal indifference displayed by other groups within American and European domestic terrains. Women’s rights, for instance, are not on the agenda of international migratory law. Violence against the black community is disbelieved by many, even among equally victimised groups by violence in the United States, such as migrants—Asians or Latinos alike[22]—and survivors of gender-based violence. ‘I can’t believe I am still protesting about this’[23] has been a common claim in feminist movements that decry Euro-based systems of law that debase women’s rights in both continents, and used in a variety of other manifestations, but the universality of the demands seems to stop with protest posters. The clustering and revindication of exclusion and violence by groups in their separate ways remain great adversaries of universal humanity, which should ultimately bring us all together to solve the indignities at hand. As the SNL sketch on the ‘five-hour empathy drink’[24] shows us, the fact we all hurt seems an unswallowable truth. An ocean of commonalities in the mistreatment of women in both continents, travestied of freedoms and empowerment, could be added into evidence to speak of the misappraisal of Western women’s ‘privileged’ position in the globe. Looking into some examples brought by streaming shows—our new serialised books—we see how the voices of ‘emancipated’ women in contemporary Europe are still muffled by the tesserae of Eurotribalist morality. In 30 Monedas, Elena suffers all the stereotypical pains of a Balsaquian in rural Spain, fetishised as a divorcee, ostracised, in agonising disbelief and gaslit by her village, only to be saved by the male protagonist;[25] in Britannia, which was supposed to educate us about the druidic force of women and ecologism, the characters fall into the same traps of love affairs and silliness as any teenager in Jane Austen’s novels;[26] and in Romulus, Ilia, who plays exhaustively with manipulation and fire—in the literal sense—surrenders to hysteria in ways that could not be any closer to a Fellini-an character and the Italian drama cliches imparted upon Italian females by genre cinema.[27] Everything old is new again, including misogyny. In this realm of using fictional history to describe women as these untamed forces of nature, Shadow and Bones, based on the books of Leigh Bardugo, makes an exception in speaking accurately of women’s leeway in past Judaism, which was inherited by ‘true’ Christianity, as the veneration of Mary—another casualty in the European alienation of religions—attests. Alina is the promised link to all cultures, and her willpower among the Grisha, a metaphoric group of Jewish people at the service of the Russian empire, promises to free them from slavery and falsity and bring light to the world, since she is the ‘Sun-summoner’—a reference, perhaps, to the woman clothed with the sun in Christianity. Confronting their distinct traits could help us understand better how the European specialism and skill in hating and oppressing has sprawled around the globe. What Social Sciences can make out of Art in the era of binge-watching remains to be seen. Let’s not speak falsely Enlightened by lessons like those, we are left by Art without a shred of doubt that (i) Science has been all but evasive and has tiptoed around the sheer simplicity of hate; (ii) the European haughtiness vis-à-vis the Americas, founded by their progeny, and the globe in a large spectrum of subjects such as gender bias, migration, racism, and climate is peevish, to say the least. Their internal struggle with all those pressing issues is tangible, and religion is not to blame; using a modicum of the counterfactual thinking allowed by Art, we can imagine a world where Europeans had decided to use Confucianism or Asatro as a means to spread their wings, only to realise the results would have hardly been any different. The very idea of a ‘global hierarchy of races’, albeit barbaric—another curious term born out of European Hellenic condescension—and one that should have fallen sharply down with the downfall of imperialism, remains entrenched in all those discussions, and Christianity has nothing of the sort to display. The same, unsurprisingly, is true of ‘development’, as a goal which is still measured in much the same ways as it was when European tribes fought among themselves, which then leads us to nothing but tautological havoc. It is as if “we don’t get it”. In the meantime, those who do get it can only look at one another, and can say nothing but “There are many here among us, who feel that life is but a joke, but you and I, we’ve been through that, and this is not our fate. So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late”. [1] Dylan’s lyrics, one has to note, do not fully convey the reeling effect of ineluctability, surrendering to the no-other-option but to fight within the bulk of indescribable feelings transliterated by Hendrix’s composition. [2] See Rosie Holt https://twitter.com/RosieisaHolt/status/1425361886330200066 cf. Marius Ostrowski, “More drama and reality than ever before” in Ideology-Theory-Practice, 23/8/2021. [3] Ostrowski, Marius. Ibid. [4] ‘Snirk’, a slang term defined by the Urban Dictionary as: “a facial expression combining a sneer and a smirk, appears sarcastic, condescending, and annoyed”. At https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Snirk [5] Appadurai, Arjun. “Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination” in Public Culture 12(1): 1–19. Duke University Press, 2000. [6] After all Popper was in the quest of a better world represented by an open society. Cf. Popper, Karl. In search of a better world: Lectures and essays from thirty years. Routledge, 2012. Cf. also Popper, Karl R. The open society and its enemies. Routledge, 1945. [7] See comments by Daniel Davison-Vecchione, at “Dystopia and social theory” in Ideology-Theory-Practice, 18/10/2021, on Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, as quoted translated by Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells, London: Penguin Books, 2002. [8] We use here Gleen Albrecht’s terminology, ‘solostalgia’, to describe the disconnection with the world in what can be our synesthetic experience in it, as well as with the feelings of fruition of this experience, from our reasoning of those experience, in a narrower version of what the author described as the “mismatch between our lived experience of the world, and our ability to conceptualise and comprehend it”. Cf. Albrecth, Glenn. “The age of solastalgia” in The Conversation. August 7, 2012. [9] Elizabeth Hinton describes ‘social grievances’ both as the cause for lynching Afro-Americans who were accused of transgressing determined rules, such as “speaking disrespectfully, refusing to step off the sidewalk, using profane language, using an improper title for a white person, arguing with a white man, bumping into a white woman, insulting a white woman, or other social grievances,” anything that ‘offended’ white people and challenged racial hierarchy (pp. 31–32 of Lynching Report PDF)”, as well as the social grievances hold by the black community as reason for the riots and manifestations from the 1960’s to present BLM. Cf. Hinton, Elizabeth. America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s. Liveright, 2021. [10] https://www.abc.net.au/religion/is-there-really-a-judeo-christian-tradition/10810554 [11] Hinton. Idem, particularly Chapter 8 ‘The System’. [12] https://upstanderproject.org/firstlight/doctrine [13] Deleuze, Gilles. La logique du sense. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1969. [14] Here we refer to Popperian concepts and notions again, principally to how he explains the nature of scientific discovery at The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge, 1959. [15] Brother Day (Lee Pace) commend his younger clone, Brother Dawn, for looking into an artifact brought by diplomats to the Imperials as a gift and the lack of a certain metal in it as a metaphor to that people need for that specific metal, therefore, an elegant request to the Galactical Empire for trade agreements, thus leading to the phrase: ‘Art is politics’ sweeter tongue’. It is not a directions quotation from the original work of Asimov in the Foundation trilogy; whether is an implication stemming from any other of his writings is unknown. [16] ‘Virtue signaling’ and ‘virtue vesting’ have been described in a variety of ways, but ‘Mr. President’ in Midnight Gospel’s pilot shed some light on the notions assuring they are rather democratic: centrists, leftists, rightists, all can use them indistinctly, since the fear of being disliked seems to be the only real motivation behind pro and cons positions, accordingly with Daren Duncan. The dialogue between Mr. President (who has no party) with the Interviewer: “Interviewer: - I know you've gotta be ncredibly busy right now with the zombie apocalypse happening around you./ Mr. President: - Yeah, zombies... I really don't wanna talk about zombies./ Interviewer: - Okay. What about the marijuana protesters?/Mr. President” -Those assholes? -Yeah. - First of all, people don't understand my point of view. - They think somehow I'm anti-pot or anti-legalisation./ Interviewer: - Right./ Mr. President: -I'm not actually "pro" either. - I'm pro human liberty, I'm pro the American system, pro letting people determine their laws./ Interviewer: -Right./ Mr. President: -I don't think this is... -If I had to... -[sniffs] ...have a... You know, if somebody pressed my face to the mirror and said,"Is it gonna be good or bad?" I think it might end up being kinda not so good for people…” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kQWAqjFJS0&t=45s [17] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mVbdjec0pA [18] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1Pl8CzNzCw [19] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NPBIwQyPWE [20] Anderson, Jem; Kelly, Justin; Mckeon, Brian. “How we kill each other? FBI Murder Reports, 1980-2014” In Applied Statistics and Visualization for Analytics. George Mason University, Spring 2017. [21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=daJZU5plRhs [22] Yellow Horse AJ, Kuo K, Seaton EK, Vargas ED. Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(5):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168 [23] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13603124.2019.1623917?journalCode=tedl20 [24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OP0H0j4pCOg [25] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdmMoAuD-GY [26] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JbFo7r_41E [27] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8wQNZ1N3T by Daniel Davison-Vecchione

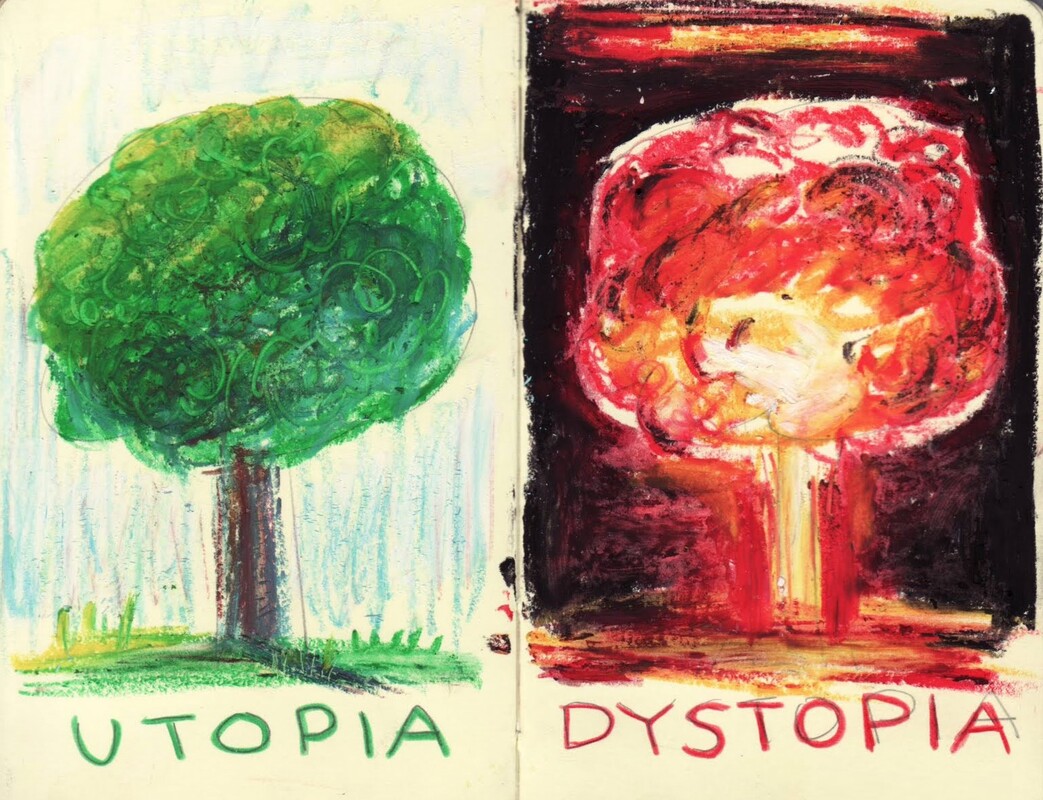

Social theorists are increasingly showing interest in the speculative—in the application of the imagination to the future. This hearkens back to H. G. Wells’ view that “the creation of Utopias—and their exhaustive criticism—is the proper and distinctive method of sociology”.[1] Like Wells, recent sociological thinkers believe that the kind of imagination on display in speculative literature valuably contributes to understanding and thinking critically about society. Ruth Levitas explicitly advocates a utopian approach to sociology: a provisional, reflexive, and dialogic method for exploring alternative possible futures that she terms the Imaginary Reconstitution of Society.[2] Similarly, Matt Dawson points to how social theorists like Émile Durkheim have long used the tools of sociology to critique and offer alternative visions of society.[3]