by Lucio Esposito and Ulrike G. Theuerkauf

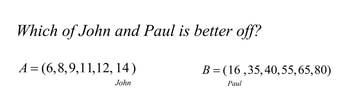

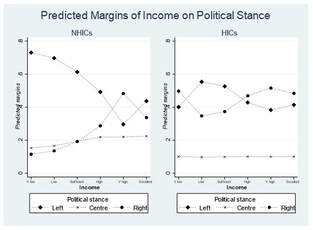

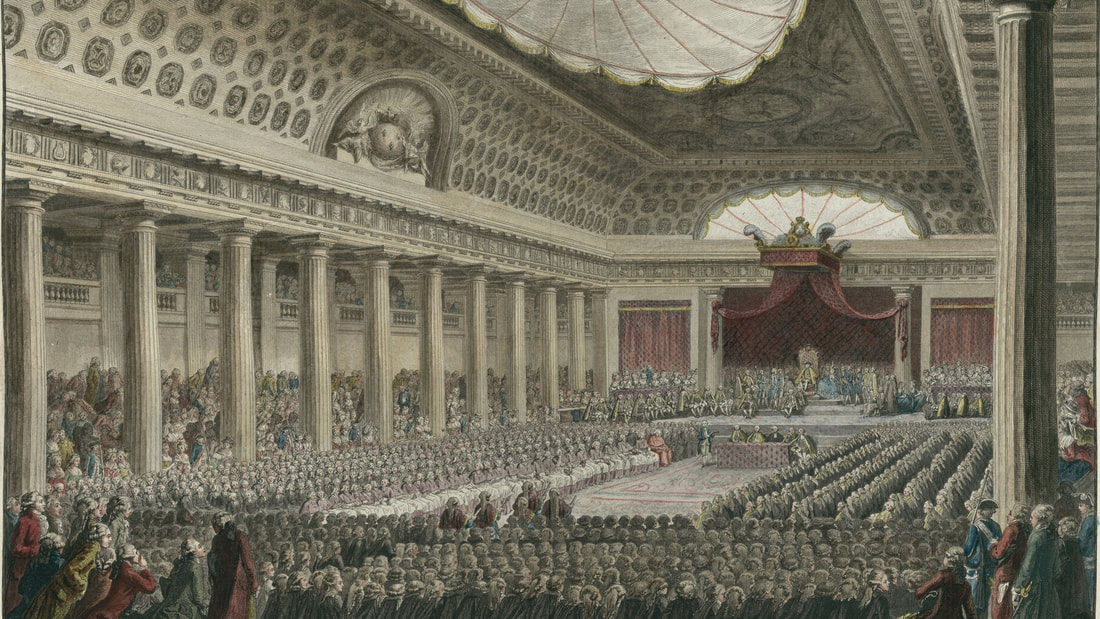

It is a well-established argument in the economics and political science literature that a country’s level of economic development has an impact on people’s political orientations. Following the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, high income levels and solid welfare provisions at the national level facilitate the fulfilment of people’s basic survival needs, so that post-materialist issues (relating e.g. to questions of multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights or the protection of the environment, rather than questions of economic survival) are likely to play a bigger role for the ideological identities of those individuals who grow up under conditions of macro-economic security compared to those who do not.[1] Based on these insights, we ask how the relationship between individuals’ understanding of what it means to be “economically well off” and their self-placements on a left-right scale may differ depending on their macro-economic context. In a novel contribution to existing scholarship, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse research participants’ political orientations. Using original data from a cross-country survey with 3,449 undergraduate students, our findings show distinct patterns for research participants in high-income countries (Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK) as opposed to those in non-high-income countries (Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya).[2] In the latter countries, research participants’ left–right orientations are associated with a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being which centres on assessments of their family’s real-life economic status. In high-income countries, by contrast, Left-Right self-placements correlate with a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being that is based on normative judgments about inequality aversion. These findings support the central tenets of Social Modernisation Theory, as they highlight the relevance of research participants’ macro-economic context for their ideological orientations. ‘Left’ and ‘Right’: A Contested but Useful Tool to Map Political Preferences The left–right distinction is a contested but useful tool to map political preferences. Tracing its origins to the seating arrangement in the French revolutionary parliament—‘where “radical” representatives sat to the left of the presiding officer’s chair, while “conservatives” sat to the right’[3]—the left–right distinction provides important ‘simplifying’ functions for the benefit of individuals, groups, and the political system as a whole:[4] For the individual, ‘left’ and ‘right’ help to make sense of ‘a complex political world’[5] around them, to orient themselves within this world, and make political decisions.[6] At the group level, ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve to summarise political programmes and, in doing so, contribute to the development of group cohesion and social trust.[7] For the political system as a whole, the left–right distinction provides shortcuts for the identification of key political actors and issues, facilitates communication between citizens and their political representatives, and helps to make political processes overall more efficient.[8] Not surprisingly, given its multiple benefits, ‘worldwide evidence shows the continued relevance of the L[eft] R[ight] divide for mass politics’.[9] At the same time, however, it is important to note that—despite its usefulness as a category of practice as well as analysis—the left–right distinction comes with a range of conceptual and empirical challenges. The arguably most notable challenge is that ‘left’ and ‘right’ have no fixed meaning, as their definition—and their specific association with attitudes towards issues such as taxation, welfare spending, multiculturalism, foreign policy, or group rights—tend to vary depending on space, time, and even individuals.[10] Previous research has identified multiple factors that influence the context-dependent meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’, including, for instance, a country’s political regime type,[11] its geopolitical location,[12] political elite behaviour,[13] and levels of economic development.[14] As scholars of International Development, we are particularly interested in the interaction effects between levels of economic and political development (here: countries’ macro-economic context and their populations’ political orientations), which leads us to Social Modernisation Theory as our analytical framework. Economic Conditions and Ideological Orientations Broken down to its central tenets, Social Modernisation Theory argues that a country’s economic conditions have an impact on its people’s political norms, values, and beliefs.[15] Put differently, economic conditions at the macro-level are seen as an important driver of ideological orientations at the micro-level, as a high level of economic development combined with a robust welfare state (at the national level) is expected to enhance people’s feelings of material security, their intellectual autonomy, and social independence (at the individual level).[16] This is because a macro-economic context of high economic development and solid welfare provisions makes it generally easier to fulfil basic survival needs, thus reduces the urgency of economic security concerns for large parts of the population, and opens up space for greater engagement with post-materialist issues.[17] As we discuss in further detail below, this is not to say that there is a linear, irreversible and unidirectional pathway of economic and political development—but rather an expectation that ideological orientations are likely to change when the macro-economic context does, too. Following Social Modernisation Theory, rising income levels and improved welfare provisions in highly industrialised societies after the end of the Second World War have had a twofold effect: on the one hand, they helped to meet crucial (material) survival needs for a majority of the population in these societies.[18] On the other, they made economic security concerns less urgent and allowed non-economic issues to become increasingly relevant for the ideological identities of those individuals who experienced macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[19] Of course, none of this is to say that economic issues cease to play a role for people’s ideological orientations once a country has reached a certain level of economic development—economic issues still matter for the content of ‘left’ and ‘right’ also in advanced industrial societies.[20] What Social Modernisation Theory does point out, however, is that the economic bases of ideological orientations may become weaker (and their non-economic bases stronger) when there is a sustained rise in levels of income and welfare provisions. Put differently, Social Modernisation Theory explains how economic conditions affect the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for people’s political identities:[21] For individuals who grew up at a time of economic prosperity and solid welfare provisions, post-materialist issues are likely to play an important role for their ideological orientations—meaning that attitudes towards issues which go beyond material survival needs and instead centre on questions of self-expression, belonging, and the quality of life (such as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism or the protection of the environment) form an important part of their political identity.[22] Conversely, materialist issues—which centre on questions of material security, such as the stability of the economy or levels of crime—are likely to play a more prominent role for the ideological orientations of individuals who did not experience macro-economic security in their pre-adult years.[23] Two qualifications are important to note at this point: First, changes in the relative relevance of materialist and post-materialist issues for the social construction of ideological identities do not happen overnight, but are notable especially in the form of intergenerational differences.[24] Second, these changes are not irreversible, as rising inequalities in the distribution of economic wealth, economic crises, and associated economic insecurities can lead to shifts in the proportion of materialist and post-materialist values amongst a given population.[25] As highlighted by authors such as Inglehart and Norris,[26] the development of ideological orientations does not follow a linear, unidirectional pathway, but is itself subject to changes and reversals depending on broader contexts, including e.g. the recession of 2007–9 or—one can assume—the current cost-of-living crisis. Irrespective of these qualifications, Social Modernisation Theory’s fundamental insight still stands, as multiple studies, using different research designs, have corroborated the political value shifts to which economic development can lead.[27] We expand on these findings by asking how the relationship between left-right political orientations and conceptualisations of economic well-being may differ depending on research participants’ location in either a high-income or non-high-income country. Economic Well-Being and Self-Placements on a Left-Right Scale In a nutshell, Social Modernisation Theory describes a process of social construction—driven by economic development—in which post-materialist issues become increasingly important for the content of ideological identities, while materialist issues decrease in relevance.[28] Following this line of argumentation, we should expect materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in non-high-income countries, and post-materialist issues to be particularly relevant for left-right self-placements amongst research participants in high-income countries. For the purpose of our analysis, we use different conceptualisations of economic well-being to quantify materialist and post-materialist value orientations. In doing so, we make an original contribution to public opinion research, as economic well-being is a widely-discussed term in the economics literature that, so far, has been hardly used in assessing political orientations.[29] In its broader meaning, economic well-being refers to the socially constructed nature of what it means to be economically well-off.[30] A more refined definition allows us to distinguish between the materialist and post-materialist dimension of economic well-being: In its materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being centres on (absolute and relative) assessments of one’s own, ‘real-life’ economic standing, which affects feelings of economic (in)security.[31] In its post-materialist conceptualisation, economic well-being reflects normative judgments about different types of economic inequality, which go beyond one’s own real-life economic standing.[32] Disaggregated into its materialist and post-materialist dimension, we can use the different conceptualisations of economic well-being to analyse correlates of ideological identities which may relate either to feelings of economic security (the materialist dimension of economic well-being) or value-judgments about economic inequality (the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being). Following the central claims of Social Modernisation Theory, we would expect left-right self-placements to be associated with the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being in high-income countries, and the materialist dimension of economic well-being in non-high-income countries. Quantifying the Materialist and Post-Materialist Dimension of Economic Well-Being Our findings are based on survey data that were collected from 3,449 undergraduate students in three non-high-income countries (NHICs hereafter: Bolivia, Brazil, and Kenya) and four high-income countries (HICs hereafter: Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2007. We rely on World Bank data to distinguish HICs from NHICs, with NHICs’ GNI per capita ranging from US$ ≤ 935 to US$11,455, and HICs’ GNI per capita at US$ > 11,455 in 2007.[33] The fact that we only include data from university students in our sample limits the external validity of our findings, which means that we cannot (and do not seek to) draw inferences for the entire population of the countries under analysis. At the same time, there are multiple benefits to gathering data from university students only, as it enables researchers to reach a relatively large number of highly literate respondents in one setting[34] and reduces the potentially confounding effect of different education levels.[35] The survey that we presented to university students asked respondents to place themselves on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extreme left’ to ‘extreme right’, with an additional option to state ‘I don’t have a political view’. In the English version of the questionnaire, this was presented as follows: How would you define your political views? o extreme left o left o centre-left o centre o centre-right o right o extreme right o I don’t have a political view To capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, we asked respondents to assess their family’s actual economic status in absolute and relative terms, by referring first to their family income without any benchmark, and then to their family’s relative standard of living compared to other families in the respondent’s country. In the English questionnaire, the relevant survey questions read as follows: How would you evaluate the current income of your family? o very low o low o sufficient o high o very high o excellent How would you compare the standard of living of your family with that of other families in your country? o very much lower o lower o almost the same o higher o very much higher Based on research participants’ answers, we coded two variables that capture the materialist dimension of economic well-being, labelled ‘Income’ and ‘RelStandard’ respectively. To capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, we use two variables that quantify respondents’ normative judgments of hypothetical inequality situations. For the first variable, respondents were asked to take the role of an external observer and assess the condition of two individuals, John and Paul, living in two isolated societies, A and B, which are identical in everything other than inhabitants’ income levels. Respondents were given six hypothetical scenarios and asked to assess whom of the two individuals (John or Paul) they regarded as being economically better off in each scenario. To illustrate, the numbers in the example below represent income vectors that describe hypothetical income distributions in societies A and B. An absolutist attitude to economic well-being would indicate Paul as being better off, because Paul has a higher income, even though John enjoys a higher hierarchical position. A relativist attitude, by contrast, would indicate John as being better off due to his relative economic standing. The six hypothetical scenarios enable us to quantify inequality aversion and, in doing so, help us to capture a post-materialist understanding of economic well-being. The variable that we derive from research participants’ answers to the six hypothetical scenarios is labelled ‘Absolutist’ and ranges from 0 to 6, depending on how many times respondents have adopted an absolutist stance in their normative assessment. The second variable to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being is derived from respondents’ answers when presented with an ‘island dilemma’ scenario.[36] The island dilemma provides a different way to quantify attitudes towards inequality aversion, and is phrased as follows in the English questionnaire: D and E are two islands where the inhabitants are identical in all respects other than income. Prices are the same in the two islands. Suppose that you have to migrate to one of them. In island D your income would be 18 Fantadollars—much lower than most people’s incomes in D—whilst in island E it would be 13 Fantadollars—the same as most people’s incomes in E. Income levels will remain constant throughout people’s lives. Where would you choose to go? Respondents’ answers were used to code a dichotomous variable labelled ‘IslandAbs’, which takes on the value 1 when respondents expressed their preference for a situation of higher income despite worse relative standing (i.e. when they chose island D) and the value 0 when respondents preferred lower income but better relative standing (i.e. when they chose island E). Both the Absolutist and IslandAbs variable help us to quantify the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being, as they focus on respondents’ normative attitudes towards economic (in)equality in hypothetical scenarios, and thus go beyond their own material conditions.[37] Economic Context Matters Having coded our key variables, we run a series of multivariate probit regression analyses to test the association between different conceptualisations of economic well-being and respondents self-placements on a left-right scale. Our control variables include respondents’ gender, age, discipline of study, year of study, their mother’s and father’s professions as well as country dummies. To reduce the risk of Type I error and potential bias in our results, we cluster standard errors at the classroom level.[38] We also conduct multiple robustness tests, available in the online appendix of our article. Overall, our empirical results lend strong support to our theoretical expectations, as we find a rather striking pattern depending on research participants’ location in a NHIC or HIC. These findings remain robust across multiple model specifications, and are illustrated in the Figures below: As can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2, the probability that respondents in NIHCs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases with rising Income levels. It is as high as 69.7% to 73.1% for students who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but only 29.6% to 43.7% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. Conversely, the probability that NHIC respondents place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases with Income, as it is only 11.5% to 13.6% for respondents who reported ‘low’ or ‘very low’ Income levels, but 48.3% to 33.8% for those who reported ‘very high’ or ‘excellent’ Income levels. The materialist dimension of economic well-being as captured in the Income variable thus clearly correlates with NHIC respondents’ political orientations. Notably, however, there are no clearly identifiable patterns for HIC respondents (see the right panel of Figure 2), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the Income variable has no discernible impact on HIC respondents’ left-right self-placements.

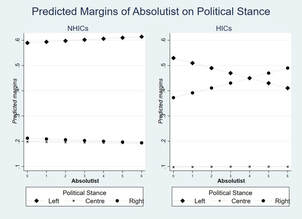

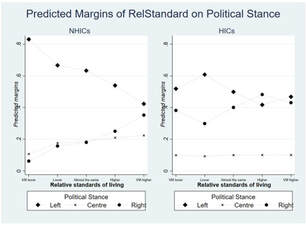

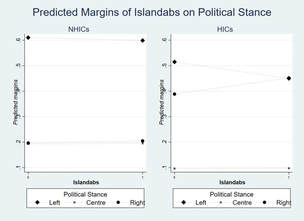

The difference between respondents in NHICs and HICs emerges rather strikingly also in Figure 3, which shows predicted values of political preferences at different levels of RelStandard. In NHICs, the probability of research participants placing themselves on the left side of the Likert scale decreases along RelStandard levels, from 83.1% for respondents who reported their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’ than others, to 42.3% for those who reported it to be ‘very much higher’ (left panel of Figure 3). Conversely, the probability that research participants place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases from 6.2% for those who report their family’s relative economic standing to be ‘very much lower’, to 35.2% for those who report it to be ‘very much higher’. As was the case for Figure 2, no clear pattern emerges for respondents in HICs (right panel of Figure 3), meaning that the materialist dimension as captured in the RelStandard variable has no discernible impact on their Left-Right self-placements either. Figures 4 and 5 contain post-estimation predicted margins of respondents’ Left-Right self-placements at different levels of Absolutist and IslandAbs—the two variables that we use to capture the post-materialist dimension of economic well-being. In contrast to Figures 2 and 3, there is no clear pattern for NHICs, as illustrated in the nearly flat lines in the left panels of Figures 4 and 5. For HICs, however, respondents’ ideological self-placements vary at different values of Absolutist and IslandAbs (right panels of Figures 4 and 5). Here, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the left side of the Likert scale of political orientations decreases from 53.0% to 41.1% along the Absolutist domain. Conversely, the probability that respondents in HICs place themselves on the right side of the Likert scale increases along the same domain from 37.2% to 49.0%. For the ‘island dilemma’, respondents in HICs who have chosen the island denoting inequality aversion are 12.7% more likely to place themselves on the left rather than right of the political spectrum. Taken together, these figures illustrate that respondents’ left-right self-placements are linked to a materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in NHICs (but not in HICs), and to a post-materialist conceptualisation of economic well-being in HICs (but not in NHICs). Conclusion Using multivariate analyses with data from 3,449 undergraduate students, we find robust empirical evidence that the relationship between research participants’ left-right self-placements and conceptualisations of economic well-being differs depending on their high-income or non-high-income context. In non-high-income countries, left-right self-placements correlate with the materialist (but not the post-materialist) dimension of economic well-being. In high-income countries, by contrast, they correlate with the post-materialist (but not the materialist) dimension. These findings support our theoretical expectations based on Social Modernisation Theory that a country’s macro-economic context affects micro-level patterns of ideological orientations. They also illustrate the usefulness of economic well-being as a conceptual tool in public opinion research, as its materialist and post-materialist dimensions help to unveil distinct patterns in the correlates of ideological orientations across macro-economic contexts. [1]. R. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977); R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); R. Inglehart and J.-R. Rabier, ‘Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality-of-life politics’, Government and Opposition, 21 (1986), pp. 456–479. [2]. The classification of Kenya as a low-income country; Bolivia as a lower-middle-income country; Brazil as an upper-middle-income country; and Italy, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK as high-income countries at the time of the survey (2007) is based on the World Bank. See The World Bank, World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format, 2019, available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . [3]. J. M. Schwartz, ‘Left’, in Joel Krieger (Ed.) The Oxford Companion To Politics of the World, [online] 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), para. 1. [4]. O. Knutsen, ‘Value orientations, political conflicts and left-right identification: a comparative study’, European Journal of Political Research, 28 (1995), pp. 63–93; P. Corbetta, N. Cavazza and M. Roccato, ‘Between ideology and social representations: four theses plus (a new) one on the relevance and the meaning of the political left and right’, European Journal of Political Research, 48 (2009), pp. 622–641. [5]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4. [6]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; E. Zechmeister, ‘What’s left and who’s right? A Q-method study of individual and contextual influences on the meaning of ideological labels’, Political Behavior, 28 (2006), pp. 151–173; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [7]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [8]. Knutsen, op. cit., Ref. 4; Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6; Corbetta, Cavazza and Roccato, op. cit., Ref. 4. [9]. A. Freire and K. Kivistik, ‘Western and non-Western meanings of the left-right divide across four continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18 (2013), p. 172. [10]. K. Benoit and M. Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2006); R. J. Dalton, ‘Social modernization and the end of ideology debate: patterns of ideological polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7 (2006), pp. 1–22; R. J. Dalton, ‘Left-right orientations, context, and voting choices’, in Russel J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson (Eds.) Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 103–125; R. Farneti, ‘Cleavage lines in global politics: left and right, East and West, earth and heaven’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 17 (2012), pp. 127–145. [11]. Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10. [12]. S. Hix and H.-W. Jun, ‘Party Behaviour in the Parliamentary Arena: the Case of the Korean National Assembly’, Party Politics, 15 (2009), pp. 667–694. [13]. Zechmeister, op. cit., Ref. 6. [14]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1. [15]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [16]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). [17]. Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; R. Inglehart, ‘Globalization and postmodern values’, The Washington Quarterly, 23 (2000), pp. 215–228. [18]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, op. cit., Ref. 10. [19]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 11; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Farneti, op. cit., Ref. 10; R. Inglehart, ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox,’ American Political Science Review, 79 (1985), pp. 97-116; R. Inglehart and P. R. Abramson, ‘Economic security and value change,’ The American Political Science Review, 88 (1994), pp. 336-354. [20]. See for instance, Benoit and Laver, op. cit., Ref. 10; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [21]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [22]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1. [23]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16. [24]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Rabier, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Globalization, op. cit., Ref. 17. [25]. R. Inglehart and P. Norris, ‘Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse’, Perspectives on Politics, 15 (2017), pp. 443–454. [26]. Inglehart and Norris, op. cit., Ref. 25. [27] See, for instance, R. A. Giacalone and C. L. Jurkiewicz, ‘The interaction of materialist and postmaterialist values in predicting dimensions of personal and social identity,’ Human Relations, 57 (2004), pp. 1379–1405; M. A. C. Gatto and T. J. Power, ‘Postmaterialism and political elites: The value priorities of Brazilian federal legislators,’ Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8 (2016), pp. 33–68; D. E. Booth, ‘Postmaterial Experience Economics,’ Journal of Human Values, 24 (2018), pp. 83–100; M. D.Promislo, R. A. Giacalone and J. R. Deckop, ‘Assessing three models of materialism-postmaterialism and their relationship with well-being: A theoretical extension,’ Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2017); pp. 531–541. [28]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart and Welzel, op. cit., Ref. 16; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [29] A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan, 1932); R. H. Frank, ‘The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods,’ American Economic Review, 75 (1985), pp. 101–116; F. Carlsson, O. Johansson-Stenman and P. Martinsson, ‘Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods,’ Economica, 74 (2007), pp. 586–598; L. Corazzini, L. Esposito and F. Majorano, ‘Reign in hell or serve in heaven? A cross-country journey into the relative vs absolute perceptions of wellbeing,’ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (2012), pp. 715–730. [30] See, for instance, Pigou, op. cit., Ref. 29; Frank, op. cit., Ref. 29; Corazzini, Esposito and Majorano, op. cit., Ref. 29. [31]. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution, op. cit., Ref. 1; Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization, op. cit., Ref. 1; Dalton, Social Modernization, op. cit., Ref. 10. [32] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [33]. World Bank, op. cit., Ref. 2. [34]. Y. Amiel and F. A. Cowell, ‘Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire’, Journal of Public Economics, 47 (1992), pp. 3–26. [35]. See also P. C. Bauer, P. Barberá, K. Ackermann and A. Venetz, ‘Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Individual-level variation in associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’ and left-right self-placement’, Political Behavior, 39 (2017), pp. 553–583; P. J. Henry and J. L. Napier 2017, ‘Education is related to greater ideological prejudice’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 81 (2017), pp. 930–942; D. L. Weakliem, ‘The effects of education on political opinions: An international study’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14 (2002), pp. 141–157. [36]. See also Y. Amiel, F. A. Cowell and W. Gaertner, ‘To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyi’s utilitarian ethics’, Social Choice and Welfare, 32 (2009), pp. 299–316. [37] Cf. also Gatto and Power, op. cit., Ref. 27; Promislo, Giacalone and Deckop, op. cit., Ref. 27; Booth, op. cit., Ref. 27. [38]. B. R. Moulton, ‘Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates’, Journal of Econometrics, 32 (1986), pp. 385–397; B. R. Moulton, ‘An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 72 (1990), pp. 334–338. 6/12/2021 There is always someone more populist than you: Insights and reflections on a new method for measuring populism with supervised machine learningRead Now by Jessica Di Cocco

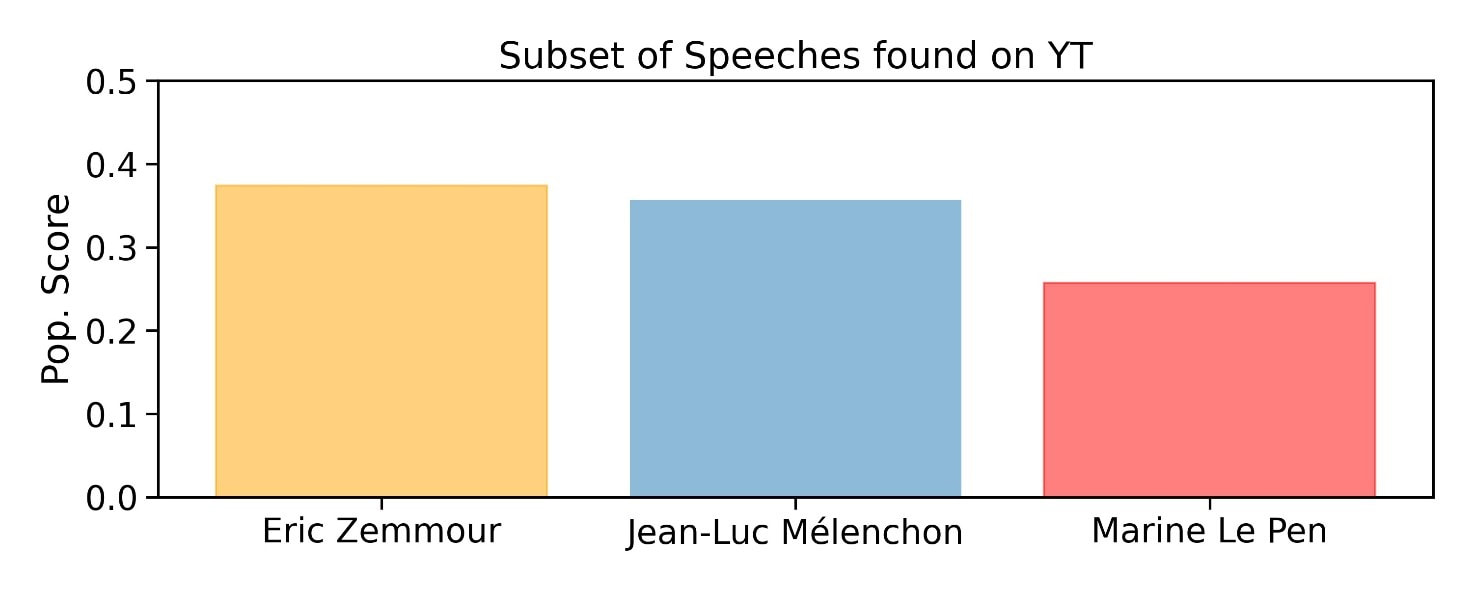

The debate on populism and its effects on society has been the subject of numerous studies in the social and non-social sciences. The interest in this topic has led an increasing number of scholars to analyse it from different perspectives, trying to grasp its facets and consider the national contexts in which populist phenomena have developed. The scholarly literature has increasingly highlighted the need to adopt empirical approaches to the study of populism, both looking at the supply side (i.e., how much populism political actors ‘offer’) and at the demand side (i.e., how much populism citizens and potential voters ‘demand’).[1] The transition from almost exclusively theoretical to quantitative studies on populism has been accompanied by several issues of no small importance concerning, for instance, problems of a statistical nature or related to data availability. From the point of view of the demand for populism, studies have shown that its determinants are numerous and often interconnected—ranging, for instance, from social status[2] to institutional trust,[3] from the deterioration of objective well-being[4] to perceptions of subjective well-being.[5] Analyses aimed at studying the causes and effects of populism generally come up against the statistical issues we mentioned earlier. Scientists familiar with empirical analyses might be aware of the problems of endogeneity, reverse causality, and omitted variables that can affect the reading of the final results. For example, the literature has often focused on the links between populism and crisis. However, the direction of what influences what (and, therefore, the causal relationship between them) remains controversial. As Benjamin Moffit has highlighted, rather than just thinking about the crisis as a trigger of populism, we should also consider how populism attempts to trigger the crisis. Populist actors participate in the ‘spectacularisation’ of failure underpinning crisis. Therefore, crises are not purely external to populism; they are internal key elements.[6] Another example concerns reverse causality. There is general agreement that economic conditions impact people’s voting choices. Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether facts or perceptions of these conditions impact more on voting choices. Larry Bartels has argued that it is not the actual economic conditions that matter, but rather that it is how this is interpreted by political parties that shapes perceptions.[7] Hence, there could be reverse causality at play, in which populist parties might impact wider perceptions of economic conditions.[8] From a populist supply perspective, studies have long focused on the classifications that scholars in the field have periodically drawn up.[9] Other scholars have gradually adopted alternative methods, such as focusing on the textual analysis of programmes, speeches, and other textual sources of leaders and parties. Our work is situated within this field of research on populism and, more generally, on ‘populisms’. We use the plural because we refer to different forms of populism that can develop along the entire ideological continuum and in very diverse national contexts. The diversity in the forms of populism has called for a deeper reflection on how we can compare them across the countries and measure them to consider the possible intensities and nuances. Measuring populism Indeed, one of the main challenges in comparative studies on populism is how to measure it across a large number of cases, including several countries and parties within countries. We address this issue in our recent work, in which we use supervised machine learning to evaluate the degrees of populism in evidence in party manifestos.[10] Previous literature had already explored the possibility of using different methods, including textual analysis,[11] [12] and machine learning has cleared the way for further research in this direction. What are the advantages of using automated text-as-data approaches for investigating diversified political questions, populism, and others? For example, these techniques allow for the analysis of large quantities of data with fewer resources, inferring actors’ positions directly from the texts, and obtaining more replicable results. Furthermore, they make it possible to focus on elites and their ideas,[13] and thereby obtain continuous populism measures which, unlike dichotomous ones, better account for the multi-dimensionality of populism and differentiate between its degrees.[14] Finally, automated textual approaches can help capture the rapid changes and transformations of the party landscape. We used automated textual analysis to derive a score which acts as a proxy for parties’ levels of populism. We validated the score using different expert surveys to check its robustness and verify the most correlated dimensions based on the literature on populism. We obtained a score that we can use to measure parties' levels of populism per year and across countries. In an ongoing study, we have applied the score for testing the Populist Zeitgeist hypothesis. According to Cas Mudde,[15] a populist Zeitgeist is spreading in Western Europe, which means that non-populist parties are becoming increasingly populist in their rhetoric in response to populists’ increasing success. We found that the entrance of populist contents into the debate within non-populist parties seems to be an Italian peculiarity. Prompted by this finding, we started investigating the possible issues connected with this specific trend and concluded that Italy has exhibited sharper decreases in crucial socio-economic dimensions, such as satisfaction with democracy, trust towards institutions, and objective and subjective well-being. For this exploratory analysis, we used data from European Social Survey[16] over the last two decades. The French case We can use the same method to investigate other textual sources and answer different questions within the field of populism analysis. For this purpose, we have collected a small corpus composed of 300 sentences drawn from TV interviews and debates available on YouTube and involving some of the candidates for the French Presidential Election that is due to take place in April 2022. The field of candidates is currently still somewhat unclear, since Eric Zemmour, an outsider leaning towards the far right who has enjoyed a degree of insurgent popularity in recent opinion polling, has not yet formally announced his candidacy. Given the limited availability of data, at the moment, we only focused on Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Marine Le Pen, and Eric Zemmour. Even if the corpus needs further improvement, we can already offer a number of interesting insights for more profound reflections and future studies. For those unfamiliar with French politics, the three leaders we chose for analysis exhibit radical and (or) populist traits. However, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen are already well-known to the general public, the third figure mentioned, Eric Zemmour, is new to the political scene. He has gained prominence chiefly as a controversial writer and columnist, politically positioned to the right of Marine Le Pen. Zemmour’s positions are so radical that they have succeeded in overtaking those of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National on the right, ranging from the theory of ‘ethnic replacement’ and anti-abortionism to the repeal of gay rights and nostalgia for the ‘golden age’ of French colonialism. Convicted several times for inciting racial hatred, he has recently be in court for his remarks on unaccompanied migrant minors. For this trial, he is accused of “complicity in provoking racial hatred” and “racial insult”. Interestingly, by comparison, when listening to Marine Le Pen speaking, she might appear almost moderate, if not progressive, even though she is a notoriously radical right-wing populist. Is this just a feeling, or is this the case? Undoubtedly, Zemmour’s racist and sexist statements would put many extreme right-wingers to shame, and he himself has described Le Pen as a ‘left-wing’ politician. At the same time, the familiar theories of electoral competition also teach us that the electoral arena is made up of spaces in which parties and their demands are located. On that basis, it cannot be ruled out that in the presence of such an ‘extreme’ candidate, Marine Le Pen may opt for (or find herself choosing) more moderate or progressive positions, while still maintaining her attachment to her ideology’s cardinal elements, such as anti-immigration arguments, anti-Islam positions, economic nationalism, and anti-establishment claims. In all of this, the figure of radical left-wing leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon stands out; at the time of writing this article, he is the only leader who has accepted a televised confrontation with Zemmour. Some interesting reflections also arise on how the extreme right and left can share aspects as for what they offer to their potential electorate, especially if the games are played out on populist terrain. To perform the analysis, we derived the scores by applying the methodology we proposed in our work. The algorithm that we use is capable of discriminating between sentences belonging to populist or non-populist parties of a given country. The final party score that we obtained is the fraction of sentences that the classifier considers as being more likely to belong to prototypically populist partisan speech in France. Therefore, the score measures the probability that a sentence is drawn from an speech of a prototypical French populist party. According to our analysis, Zemmour is the most populist leader, with Mélenchon close behind and Marine Le Pen increasingly isolated in the rankings (see Fig. 1 below). And Macron? What of the other candidates? At the time of writing, Macron has not yet officially launched his election campaign, limiting himself to giving speeches and interviews in his capacity as head of government rather than as a future presidential candidate. As for the other candidates, firstly they belong to more ideologically moderate parties; secondly, they are starting to give their first interviews at the time of writing. The association between moderate stances and anti-populism on the one hand, and extremism and populism on the other, is not new in the literature on populism to the extent that the terms ‘populist’ and ‘radical’ have been almost used interchangeably.[17] On the contrary, moderate parties tend to be anti-populist by nature, since they do not exhibit the traits that are typically attributed to populist actors (for example, anti-elitism, people-centrism, the Manichean worldview).[18] Although many French moderate parties have launched their electoral campaign, they are far from generating the same levels of public outcry as the three populists mentioned above. A clamour that seems to confirm the old saying that, as Oscar Wilde puts it, ‘there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about’. Even if it means finding out that there is always someone more populist than you. Conclusion For this article, we have limited ourselves to showing how our method based on supervised machine learning has allowed us to obtain quick and valuable results to start new analyses and reflections. However, we shall have to wait a little longer to build a complete and comprehensive corpus, and to validate our results with further speeches as they take place and enter French political discourse. There are many questions that deserve to be investigated in the coming months. How will the French electoral campaign evolve? Will the levels of populism increase as the presidential elections approach? Does our method allow us to distinguish between left- and right-wing populisms? Is it possible to calculate the distance (or proximity) between the various leaders’ substantive rhetoric? These are just some of the questions to ask ourselves as time goes on. We will try to provide some answers in the coming weeks and months, expanding our analysis to include new leaders, first and foremost the current President Macron, new speeches, and new validations. For now, it remains to be seen how far the populist clamour convinces others to shift in their direction. [1] Meijers, Maurits J., and Andrej Zaslove. "Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach." Comparative political studies 54.2 (2021): 372-407. [2] Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. "Populism as a problem of social integration." Comparative Political Studies 53.7 (2020): 1027-1059. [3] Algan, Yann, et al. "The European trust crisis and the rise of populism." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017.2 (2017): 309-400. [4] Guriev, Sergei. "Economic drivers of populism." AEA Papers and Proceedings. Vol. 108. 2018. [5] Guiso, Luigi, et al. Demand and supply of populism. London, UK: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2017. [6] Moffitt, Benjamin. "How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism." Government and Opposition 50.2 (2015): 189-217. [7] Bartels, Larry M. "Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions." Political behavior 24.2 (2002): 117-150. [8] van Leeuwen, Eveline S., and Solmaria Halleck Vega. "Voting and the rise of populism: Spatial perspectives and applications across Europe." Regional Science Policy & Practice 13.2 (2021): 209-219. [9] Van Kessel, Stijn. Populist parties in Europe: Agents of discontent?. Springer, 2015. [10] Di Cocco, Jessica, and Bernardo Monechi. "How Populist are Parties? Measuring Degrees of Populism in Party Manifestos Using Supervised Machine Learning." Political Analysis (2021): 1-17. [11] Jagers, Jan, and Stefaan Walgrave. "Populism as political communication style." European journal of political research 46.3 (2007): 319-345. [12] Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels. "Measuring populism: Comparing two methods of content analysis." West European Politics 34.6 (2011): 1272-1283. [13] Hawkins, Kirk A., et al. "Measuring populist discourse: The global populism database." EPSA Annual Conference in Belfast, UK, June. 2019. [14] Zaslove, A. S., and M. Meijers. "Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach." (2020). [15] Mudde, Cas. "The populist zeitgeist." Government and opposition 39.4 (2004): 541-563. [16] https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ [17] EUROPE, POPULIST RADICAL RIGHT PARTIES IN, and C. Mudde. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge university press, 2007. [18] Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. "The ideational approach to populism." Latin American Research Review 52.4 (2017): 513-528. Fig. 1: The ranking of the leaders based on their TV speeches and debates. The corpus is a sample of speeches, further sentences will be added to expand the analysis to other leaders and validate the results.

by Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien

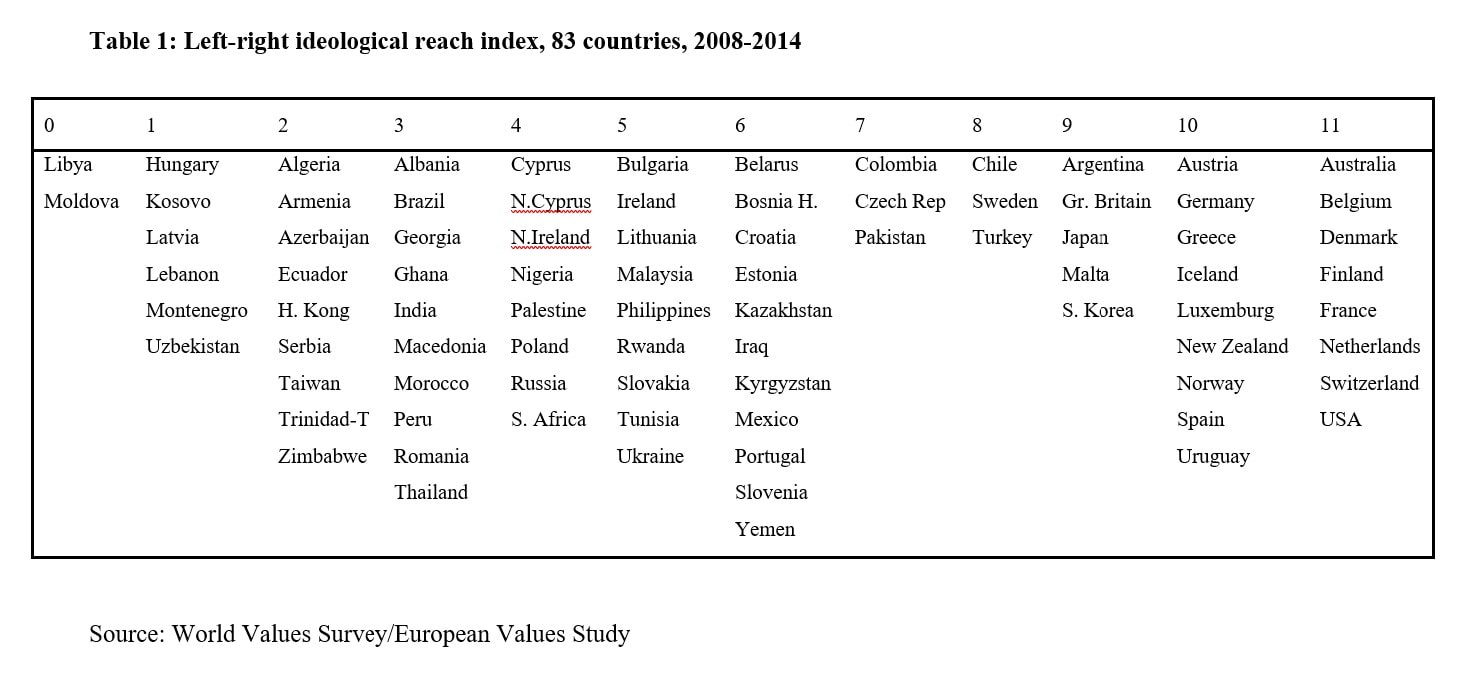

In recent years, several analysts have contended that the old cleavage between left and right has faded gradually, to become less central politically than it once was. The end of communism, the unchallenged victory of market capitalism, and the rise of neoliberalism narrowed the distance between parties of the left and of the right, and reduced the range of options available in political debates. Yet, although the left-right distinction may have become blunter as a cognitive instrument for politicians and voters, numerous studies show that it has not been replaced. In fact, no ideological cleavage is more encompassing and ubiquitous than the opposition between the left and the right.[1] When asked, most people across the world are able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, which basically divides those who support or oppose social change in the direction of greater equality. Ideological self-positioning also tends to be in line with the values and policy preferences associated with one of the two sides. The strength of this left-right schema, however, varies significantly among countries. In some cases, left-right positions correlate strongly with expected attitudes about equality, the state, the market, or social diversity; in others, they do not. We know little about the factors that make the left-right opposition more or less effective in structuring national debates. At best, existing studies suggest that left-right ideology is a more powerful constraint in Western democracies than elsewhere. To assess this question, we have taken the measure of cross-national variations in left-right ideology in 83 societies, and linked them to various factors, including economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy. Instead of focusing on individual determinants of ideology such as social class, gender or education, as scholars generally do, our analysis looks at country-level survey evidence and evaluates how, in each country, political debates are framed, or not framed, in left-right terms. The idea, along the lines suggested by Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, is to take the mass attitudes measured by large-N comparative survey projects as “stable attributes of given societies,” and as indicative of a country’s elites’ success in structuring politics along left-right dimensions. More specifically, we consider answers to twelve survey questions that capture the standard dimensions of the left-right political distinction. All answers were collected between 2008 and 2014 through the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS). The twelve questions include, for each society, one on individual left-right self-positioning, and eleven related to issues that have historically divided the two sides. The varying degree of ideological consistency in citizens’ responses then makes it possible to assess the architecture of a country's political debates and make cross-national comparisons. This approach to the workings of left-right ideology has two advantages. First, it moves the discussion of ideology beyond Western countries, and makes it possible to draw an extensive map of national ideological patterns. Second, and more importantly, because we use aggregate survey evidence, we can assess national-level causal mechanisms, and weigh, in particular, the respective influence of economic, social, and political factors on the constitution of the left-right cleavage. Our results indicate that the left-right opposition is unevenly effective in structuring national politics. Individual answers to questions about equality, personal responsibility, homosexuality, the army, churches, or major companies correlate with left-right self-positioning in more than half of the countries considered. But answers to questions about abortion, government ownership of industry, competition, trade unions, or environmental groups correlate with ideological self-positioning in only a third of the cases. In line with the expectations of Inglehart and Welzel, we also find that economic development, secularisation, and the age of democracy are the best predictors of a structured left-right debate. Theorising left and right The construction of ideological identities is both a top-down and a bottom-up process, whereby people adopt political orientations defined by elites and institutions in line with their own personal predispositions. Psychologists have naturally paid more attention to the bottom-up, personal determinants of ideology, while political scientists have been more interested in the top-down, collective process. As a top-down process, the building of the left-right divide hinges on a country’s elites’ and institutions’ capacity to propose to voters what Paul Sniderman and John Bullock call a “menu of choices.” For these authors, political institutions—most notably parties—give consistency to the views of ordinary citizens, by providing coherent menus from which they can choose. As left-right self-positioning is strongly correlated with partisanship, we can hypothesise that a long-established, institutionalised party system contributes to structure ideological debates along left-right lines, compared to the more volatile politics of countries with fragile democracies. To evaluate if the “menu of choices” proposed by a country’s elites and parties and adopted by voters is organised along left and right lanes, we test whether divisions in a country’s public opinion appear consistent with individual left-right self-positioning. People on the left are likely to be more favourable to equality, state intervention, public ownership, and trade unions, and people on the right better disposed toward markets, individual incentives, competition, and major companies. The left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion and more supportive of environmental organisations, and the right more at ease with churches and the armed forces. In countries where the menu of choices is strongly structured by the left-right opposition, there should be significant relationships between individual left-right self-positioning and the expected attitudes on these questions; in countries with a less powerful left-right schema, these relationships should be weaker. Moreover, one should expect a connection between the structure of left-right discourse and the human development sequence identified by Inglehart and Welzel. Economic development, secularisation, and democratisation broaden the possibility, the willingness, and the rights of people to consider social alternatives. Economic development fosters the material capacity of a people to make choices, secularisation expands the moral frontiers of available choices, and democratic consolidation allows political parties and groups to define over time a menu of choices ordered around the usual left-right patterns. Left-right patterns should thus be associated with these three dimensions of human development. Methodology 83 societies have a complete set of WVS/EVS answers for the questions we select. The core question of interest concerns left-right self-positioning, and it is addressed by asking respondents to locate themselves on a 1 to 10 scale going from left to right. Although the rate of response varies significantly across countries, overall, about three-quarter of respondents proved able to locate themselves on a left-right scale, allowing for valid inferences about ideology. To verify whether this left-right positioning corresponds to consistent ideological stances, we correlate left-right positioning to responses on substantive political issues. Some of our eleven ideological questions refer to the core socio-economic components of the left-right cleavage (attitudes about equality, private or public ownership, the role of government, or competition), others concern cultural or social values (attitudes about homosexuality and abortion), and others tap respondents’ views about various organisations (churches, the armed forces, labor unions, major companies, and environmental organisations). We expect people on the left to be more favourable to equal incomes, public ownership of business or industry, and the government’s responsibility “to ensure that everyone is provided for,” and less likely to consider that “competition is good.” Respondents on the left should also be more open toward homosexuality and abortion, and more confident in labour unions and environmental organisations, but less so in the churches, the armed forces, and major companies. Using national responses to our eleven questions on substantive issues, we build a composite dependent variable, called left-right ideological reach. This variable measures the extent to which, in a given country, left-right self-positioning predicts the expected ideological stances on substantive political issues. If, in country A, the relationship between self-positioning and, say, attitudes about equality is significant (p < 0.05) and in the expected direction, we give a score of 1, and if not of 0. Adding results for eleven questions, a country’s score for left-right ideological reach can then range from 0, when self-positioning never correlates in the expected direction with a substantive left-right political division, to 11, when the expected relationships are present for all questions. To account for national differences in ideological reach, we use indicators for economic development, secularisation, and democratic experience, as well as a number of control variables, for cultural differences in particular. Results Left-right ideological reach varies significantly across countries, from 0 for Libya and Moldova to 11 for a number of Western countries, including France and the United States. As Table 1 shows, there are 27 countries with scores of 0 to 3, where left-right self-positioning hardly predicts respondents’ positions on traditional issues dividing the left and the right; 31 where left-right ideological reach is moderate, with scores of 4 to 7; and 25 where a person’s ideological self-positioning predicts her position on most issues, most of the time, with scores of 8 to 11. This is a new, multidimensional, and country-scale representation of left and right public attitudes across the world, and the idea of a relationship between left-right self-positioning and substantive political orientations appears validated, at least for nearly two thirds of our sample.

A cursory look at the data suggests, in line with the literature and with our theory, that left-right ideological reach is influenced by economic and democratic development. Countries with high scores in Table 1 are predominantly rich, established democracies; countries at the low end of the scale tend to be poorer, with authoritarian regimes or newer democracies. Indeed, economic development, measured by GDP per capita, is strongly correlated with ideological reach, and so are our indicators of secularisation and democracy. In multiple regressions, the three explanatory variables considered are significant, with democracy coming first. Control variables for cultural differences (religiosity and civilisations) are non-significant. These results are consistent with our interpretation of the left-right divide as a political construct that has global resonance but is clearly more structured in countries that have long experienced economic development, secularisation, and democratic politics. They also dispose of the seemingly common sense but misleading argument that would jump from a look at the cases in Table 1 to the conclusion that left and right are a Western specificity. Looking closely at the same table, one can see countries like Uruguay, Argentina, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Pakistan with scores of 7 or more, and countries like Hungary, Taiwan, and Brazil with low scores. Fostered by economic development and to some extent by secularisation, the left-right cleavage remains, first and foremost, a product of the enduring democratic conflict for control of the government. Not surprisingly, a host of comparative politics writings lend support to this conclusion, and suggests that the left-right divide is more structuring in countries with a strongly institutionalised party system. Conclusion The evidence from cross-national surveys is rather clear: around the world, most people are able and willing to locate themselves on a left-right scale and when they do, they tend to understand what this self-positioning implies. Their understanding, however, tends to be more comprehensive in countries that are more advanced economically, more secular, and more solidly democratic. As political parties compete for the popular vote, they construct an ideological pattern that makes sense for both elites and voters, and that gives structure to politics. When they fail to do so, or when democracy is non-existent, political discourse remains more haphazard, driven by context and personalities. To go beyond these conclusions, we would need to probe further the political mechanisms that contribute to the development of ideology. Looking systematically at the party system institutionalisation hypothesis, in particular, would seem promising. For now, however, we can be satisfied that the language of the left and the right seems to function as an imperfect but critical unifying element in global politics. [1] Russell J. Dalton, ‘Social Modernization and the End of Ideology Debate: Patterns of Ideological Polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7:1 (2006), pp. 1-22; John T. Jost, ‘The End of the End of Ideology’, American Psychologist, 61:7 (2006), pp. 651-670; Peter Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 206-222; Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien, Left and Right in Global Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); André Freire and Kats Kivistik, ‘Western and Non-Western Meanings of the Left-Right Divide across Four Continents’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18:2 (2013), pp. 171-199. by Rieke Trimçev, Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, and Friedemann Pestel

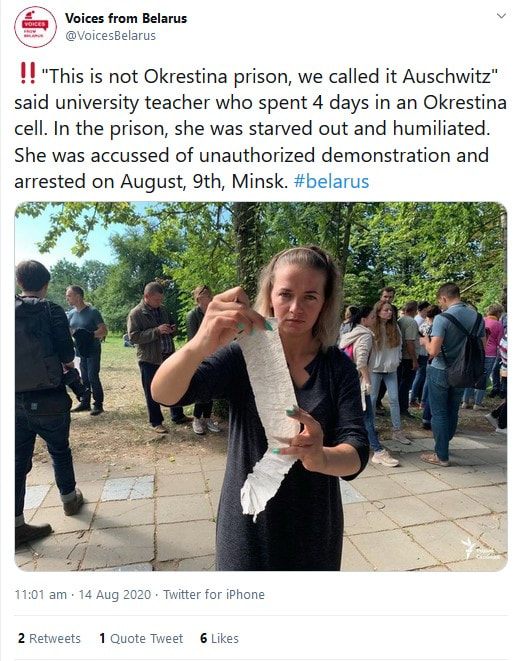

During the upheaval against Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus after the contested presidential election in August 2020, the idea of ‘Europe’ has often been invoked. These invocations might be surprising, given that Belarusians themselves have shunned explicit references to the EU and that EU flags were absent on the country’s streets. Instead, a rhetorical call to Europe has served to amplify demands for the support of Belarusian society and direct Europe’s attention to a country long-neglected by the international community. Lithuania’s former foreign secretary stated on Twitter: “The 21st century. The heart of Europe – Belarus. A criminal gang a.k.a. ‘Police Department of Fighting Organized Crime’ terrorizing Belarusians who have been peacefully demanding freedom and democracy for already 80 consecutive days. Shame!” Designating a particular region as “the heart of Europe” is a popular rhetorical device, acting as a way to call for attention. During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Margaret Thatcher used the metaphor to denounce the E.C.’s failure to prevent the mass killings in Bosnia: “this is happening in the heart of Europe […] It should be within Europe’s sphere of conscience.” The force of this phrasing defies geographical reality and lies in elevating specific values and principles as central to the idea of Europe. Europe’s political activity should live up to these values, simply to protect a vital part of its body. Through this formula, places like Belarus or Bosnia become part of a shared mental map, understood as a “spatialisation of meaning [that] dwells latently in the minds of individuals or groups of people.”[1] Another look at the rhetoric of the Belarusian protests indicates that shared representations of the past and the language of memory are particularly powerful tools in spatialising meaning and increasing the visibility of regional events for a transnational audience. All these tweets and pictures compare the Okrestina Detention Centre in Minsk, where many of the protesters were interned, to the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. Leaving aside the question of whether such comparisons are appropriate, their implication for protesters is clear: “The heart of Europe” is where Europe’s founding norm of “Never again!” is at risk.

The spatialised communication of normative arguments are at the core of our ongoing research project on the contested languages of European memory—“Europe’s Europes” if you will. It is informed by a larger qualitative study, in which we study public ideas of Europe through the prism of representations of the past and the language of memory. Examining press discourse in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2018, we have reconstructed several entrenched mental maps of Europe, which differ according to regional perspectives, ideological stances or historical trajectories. Some of these imaginaries—“Europe’s Europes”—complement each other, while others stand in open or implicit contradiction and provoke conflicts over the mental geography of Europe. To say that they are “entrenched” mental maps means that they are deeply rooted in everyday thought-behaviour and help to make sense of today’s political challenges. It is here that the language of memory, whose importance in forming shared senses of identity has long been noted, shows its ideological pertinence even beyond debates over memory politics strictly speaking.[2] Understanding these mental maps allows us to better seize discursive deadlocks, but also to identify missed encounters in debating in, over and with Europe. Islands of consensus The metaphor of the “heart of Europe” pictures Europe as a body whose different parts naturally work together to assure the functioning of a holistic “community of values”. While this metaphor might sound unsurprising, it turns out to be a concept that has a limited discursive reach, and is of limited agency when it comes to everyday political debates beyond grandiose speeches. In our study, we found that Europe is predominantly understood as a contested idea. Most of the deep-rooted mental maps spatialise this contestation through imaginary borders, both internal and external. Against the predominance of these fractured mental maps, ideas of Europe as a consensual community of values appear as “islands of consensus” of limited discursive reach. Between 2004 and 2018, one such “island of consensus” structured significant parts of the Italian press discourse, where Europe was pictured as a continent united through a canone occidentale, embracing Antiquity, Judaeo-Christian roots, Enlightenment, Liberalism, and other historical cornerstones with a positive connotation. This idea of a European canon also occurs in other national discourses but is more partisan. Especially in times of crisis, speaking from within a community of values has allowed for a clear yardstick of judgment. For example, the failure to set up a joint accommodation system for migrants in 2015, from the viewpoint of this mental map, appeared to betray European memory—a memory which had claimed a humanitarian impetus when boatpeople had fled from communism in the 1970s and 1980s: “On the issue of immigration, the Europe of the single currency and strengthened political governance seems less cohesive and less aware than Europe at the time of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War. The memory of the new Europeans and the new ruling classes seems indifferent to recent history.”[3] Yet, the moral self-confidence of dwellers of an island of consensus comes at some cost. From the perspective of an island of consensus, conflicts appear as a misunderstanding that could be solved by proper integration, inclusive of a European memory. However, this perspective remained largely confined to Italy and found little echo in other discursive spheres. Frictions between ‘East’ and ‘West’ A particularly prominent way of spatialising the meaning of Europe revolves around an East-West divide. While it is prominent both in ‘old Europe’ and those post-communist countries that joined the EU in 2004, it must be understood as the junction of two different, and in fact competing mental mappings. For France and Germany, ‘Eastern Europe’ largely represents a mnemonic terrain on which, after 1945, the communist regimes froze the memories of World War 2 and the Holocaust, and which still today rejects communist rule as an external imposition on its societies. Hence, post-communist societies are expected to catch up with the successful travail de mémoire or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which are associated with Western European societies. The ‘West’ is pictured as a spring of impartial rules for facing the past, rules that might in principle flow into the Eastern periphery to resuscitate withered memories. This even seems a precondition for the kind of dialogue suitable for bridging the often-decried East-West divide. From a Polish perspective however, the question of an East-West divide is not one of rules for remembering, but about determining a factual historical truth. “For Western elites it is difficult to accept that history for Eastern Europeans does not end with Hitler and the extermination of the Jews.”[4] It is the recognition of these truths and the national histories of suffering that is seen as the precondition of dialogue. From the perspective of this mental map, historical analogies can also serve to strengthen Poland’s position in the EU, for instance, when Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk likened Germany’s North Stream 2 pipeline to the Hitler-Stalin-Pact that had divided Poland and all of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. As the pipeline was “precisely such an agreement over the heads of others,”[5] it appeared impossible in the context of European integration in the 21st century. Periphery or boundary? Another entrenched way of mapping Europe proceeds not from its internal divisions, but from its external demarcation: Where does Europe end, or, how far does Europe reach? Again, in public discourse, asking this question serves to spatialise the strife over Europe’s core values. Over the 2000s and 2010s, the position of Turkey on Europe’s mental map has been the occasion to answer this question. And as for the East-West divide, what we observe is in fact a competition between two mental maps. From an affirmative perspective, Europe represents a clearly demarcated space, based either on conservative values such as its “Christian roots” or radical Enlightenment principles which are framed as universal and secular values. A test case for the latter was the recognition of the mass killing of 1,5 million Armenians as genocide—Europe had to end where this recognition was refused. French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy, at that point in favour of Turkish EU-membership, formulated the point very clearly: “amongst the criteria fixed by Brussels for the Turkish entry into the European Union, the most important condition is lacking: the recognition of the Armenian genocide. . . . During the genocide, Turkey attempted to amputate itself of its European part. This was a genocide, and a suicide.”[6] From the viewpoint of a competing mental map, Europe appeared rather as an open space, reflexive of its own history and its cultural, historical, and religious diversity. The political motives supporting the image of such an open Europe were highly heterogeneous. From a British viewpoint, Turkey’s EU membership ambitions represented a welcome occasion for renegotiating power relations within the EU and allowed the UK to articulate more utilitarian attitudes towards European integration. For Polish conservatives, Turkey presented an alternative to a model of integration marked by secularisation and unquestioned Westernisation. Instead of further secularising Turkey, they favoured a religious turn in European integration. Accordingly, the “conservative Muslim” went to the mosque on Fridays and “the conservative Pole” to church on Sundays.[7] Jeux d’échelles A last way of mapping Europe becomes evident in the question of how Europe links to the global context. This question is of particular importance in British discourse, where memories of the Empire project a national mnemonic order onto Europe. It is noteworthy indeed that other post-imperial countries such as France, Germany, Spain or Italy do not develop on this global component through a discussion of their past. Theresa May’s call for a “truly global Britain” which had the ambition “to reach beyond the borders of Europe” testifies to how, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, British spatial imaginaries were pitted against Europe, often referencing the UK’s more flexible economy as much as the historical grandeur of a Britain before European integration. Other countries explicitly reject such framings, but do not include perspectives from outside an alleged Europe either. The discourse on ‘European memory’ mostly relied on the ‘world’ to talk exclusively about Europe. Diverging ideas of Europe beyond conflict and consensus Mental maps of European memory stake claims of what constitutes Europe, who belongs to it and where the continent ends. In the mental maps sketched out here consensus is restricted to Sunday-best speeches and the Italian canone occidentale that exemplifies a form of model Europeanism. In contrast, the other spatial imaginations rely on the conflictive character of ‘European memory’ and demarcate the continent from an internal, external or global other. These findings provide a deeper understanding of European memory underpinning ideas of European integration and may also serve for further analysis of conflicts over the idea of Europe itself. In our future research, we will inquire into the diachronic shifts of these mental maps: they reveal the entangled relation between European integration and disintegration as scenarios for a future Europe. [1] Norbert Götz and Janne Holmén, ‘Introduction to the theme issue: “Mental maps: geographical and historical perspectives”’, Journal of Cultural Geography 35(2) (2018), 157. [2] Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, Daniela Mehler, Friedemann Pestel, and Rieke Trimçev, Europäische Erinnerung als verflochtene Erinnerung – Vielstimmige und vielschichtige Vergangenheitsdeutungen jenseits der Nation (Formen der Erinnerung 55) (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht unipress), 2014. [3] ‘Sfide dopo il no di Londra’, Corriere della Sera, 18.05.2015. [4] ‘Stalinizm jak nazizm’, Rzeczpospolita, 23.02.2008. [5] https://emerging-europe.com/news/polish-minister-compares-nord-stream-2-with-molotov-ribbentrop-pact/ [6] ‘Ma non si può parlare di adesione se non si scioglie il nodo del passato’, Corriere della Sera, 23.1.2007. [7] ‘Masowa imigracja to masowe problemy’, Rzeczpospolita, 25.07.2015. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed