by Aline Bertolin

‘There must be some kind of way out of here, said the joker to the thief’.[1] Except there isn’t. We all know it; some have known for longer. We stand bewildered before the cusp of a new world once promised to us fading away at the horizon. A world that may be within reach elsewhere, who knows; a unified world some minds and hearts glimpsed, and that perchance still hides in an Einsteinian fifth dimension amidst a warren of other hatching modern truths that we are still striving to decipher and from whose weight we can get no relief. And the thieves, and the jokers, and all the other outcasts seem to have the upper hand in this state of ideological affairs because they have known since jadis that there is no rest for the wicked: the game is rigged, and it has always been. It might be time we listen to them.

Truth and certainty Science is certainly not answering the paramount questions on this quantic leap we have failed to take. It has become too deeply entrenched in the current ‘nice v. nasty Twitter game’[2] and its ‘hermetically self-contained, self-referential certainty’.[3] Meanwhile, the portal to that dimension of global solidarity—where supranational and international institutions united would enhance development throughout the globe, development that we are all geared up for—is closing. The inheritance of this quest remains with us, nonetheless: the neuroplasticity and semantics created by the language of snaps and ‘snirks’[4] of the noosphere, carved by the ‘anxieties of the global’,[5] led us to fear, numbness, and exhaustion, a direction diametrically opposed to the ‘spirit of solidarity (Solidaritätsgeist) promised by globalism; their ways certainly have not spared Science either. Au contraire, it has plastered it together with all our gnoseological senses, which would have caused Popper’s dismay,[6] and curbed it in a much harder shell than the one envisaged by Max Weber[7]—a shell of virtue-signalling and fear. And that fear disconnected us from each other, and that shell became the equivalent of a platonic cave of over-assumptions. Hiding in our certainties only made us feel even more acutely the ‘solostalgic’[8] effects of both. If self-absorption and overreaching are what is holding us back from taking that leap, the supplicant question, borrowing the term from coding, is: how did it start, so how can we end it? Reading the works of fellow social scientists about European ideology being tantamount to the book of revelation of exclusion, an analogy emerges with some neo-Durkheimian tools that are lent powerful new sophistication by Elizabeth Hinton’s ‘social grievances theory’.[9] The effervescent ideas on how, from Europe to the globe, the Judeo-Christian morality—not tradition, for terminology’s sake[10]—is the proto-code deeply rooted into the code of law and ethos by which we live, which thus must answer for the ‘unweaving’ of people from the fabric of contemporary society, could be neatly tied together with some of the causes in Hinton’s depiction of what lit ‘America on Fire’.[11] It gives us the sense, though—and history has seemed to agree—that religious affiliations were rather a pitiful root cause. While the effects of the ‘discovery doctrine’ are well-documented and deeply-felt by many hearts across the globe,[12] so too is the scapegoatism of blaming religion for historical upheavals. Gender bias, labour un-dignification, racial hierarchisation knotted by a rating of intellectual capital to ethnicities, among the vast spectrum of pain as we now know inflicted on humans by debasing individuals and populations for what they hold dearest in their existential core, seem to be a modus operandi esquisé by Europe. A carrefour of civilisations, as many other geopolitical spaces were from age to age, Europe misappropriated ideas plentifully, and it certainly cannot be denied the position of the epicentre of postmodern ideological mayhem;[13] rather it seemed to have ‘nailed it’—since it was ‘Europeans’ who crucified the Jewish Messiah, and who disenfranchised him and his disciples from their beliefs of communion and universality, putting in motion the whole shebang of religious morale to be spread around the globe, in the same way as one has to admit that Islam started as a countermovement to save Europeans from doing precisely this, just to become their next disenfranchising target. Approaching Eurocentrism to this end in Social Sciences’ turf, was, therefore, nerve-wrenching. In contemporaneity, all scientific fields seem to share the sense of being cloistered by Science’s own gregarious endogenies, taunted by the reality of postmodern global pain. This is because scientific results stem from the same source of common cravings for logic,[14] cleaved only by the appeal such results may have to peer-reviewing and method; as society now stands, their gratification has been dangling on a fickle flow of likes and shares as much as any other gnoseological reasoning. Thus, unsurprisingly, the closing of the portal to the realm of necessary ideological epiphanies laced by humanism has received a more lucid treatment from fantasy and fiction, in other words, from Art. ‘Art and epistemology’ makes for an enticing debate, but remaining with the aspect of art being the disavowed voice in logic’s family midst, cast out by epistemological puritanism—like the daughter in Redgrave’s painting, ‘The Outcast’—is just enough to bring ourselves to see its legitimacy in leading the way towards unspeakable truths. In the adaption of Isaac Asimov’s masterpiece, Foundation, Brother Day says ‘art is politics’ sweeter tongue’[15]—but it can also be, and it often is, ‘tangy’. In the comfort of our successful publications and titles, we gave in to the idea of abdicating the freedom to speak about the truth as an essential step into Socratic academic maturity. How truth has become an intangible notion in the mainstream of the social sciences and a perilous move in the material world of politics—as Duncan Trussel so trippily, yet pristinely, described in Midnight Gospel[16]—is another story. To the outcasts making sense of contemporary times through art, nevertheless, this comfort was not agreed-upon; even less so, and principally, among the economic and societal outcasts stripped from their dignity. Living at the sharp end of this knife, they had to muster wisdom with every small disaster,[17] and, with hearts of glass and minds of stone torn to pieces, face what lay ahead skin to bone;[18] and then to fall, and to crawl, and to break, and to take what they got, and to turn it into honesty.[19] Science as it stands, relying on applauses, can hardly tap into this ‘real-world’; whereas Popperian truth and critical reasoning are in short supply. Mustering the voices from the field and presenting them to our fragile certainties and numbed senses has been the work of Art. Eurotribalism, Americanism, and Globalism In ‘How we kill each other’, a team of data scientists looking into the US Federal Bureau of Investigation succeed in clustering profiles of murder victims across all the states with the aim of discerning more information about the relevant perpetrators. They explored a data set from the FBI Murder Accountability Project, identifying trends in a thirty-five-year period (1980–2014) of murders, looking to build a predictive model of the murderer’s identity based on its correlations to victims’ traits—age, gender, race, and ethnicity—and murder scenes. Grouping victims’ profiles could prove to be useful in identifying, in turn, a murderer’s type for victims[20]. While facing difficulties in achieving this goal, the research results were insightful in confirming some typical depictions of crimes in the US—the mean murder in the prepared data set is a thirty-year-old black male killing a thirty-year-old black male in Los Angeles in 1993, using a handgun—but also revealing different clusters of perpetrators tied to uncalled-for-methods of murder, for instance, women’s prevalent use of personal methods, involving drug overdoses, drowning, suffocation, and fire, going against the expectation of females ‘killing at distance’. The spawn of novelty introduced by this research seemed to have less to do with ‘how’ Americans kill, but ‘how consistently’ Americans kill within certain groups, i.e., in proximity. In all clustered groups, crime seemed to be the result of an outburst against extenuating circumstances specific to that type of crime. And, though a disreputable fact, it is also one of rather universal than domestic interest. The social grievances in American society studied by Hinton can be pointed to as causes of this consistency in ‘proximity violence’. They have been, moreover, better approached by Art than Science during our unbreathable times. Art has certainly done a better job of giving us hints about the roots of the evil of contemporary violence. Looking at the belt of marginalised people around society, Art has been trying to tell us to grieve together, appealing to our senses and the universality of pain. It has moreover educated us on the remittance of public outcry for the protection of fundamental rights in the history of the US. How guns have been used unswervingly and in deadly ways in this peripheric belt that surrounds the nucleus of entitlement, and in ways that those communities victimise themselves rather than any other group, speaks volumes about ideological global dominance, where the echoes of past Eurocentric ideology can still be heard. Sapped of all energy and aghast of being praised for their ‘resilience’, the African descendants’ forbearance from acting against unswerving European subjugation was counterbalanced by cultural resistance. It made the continent richer beyond the economical sense, i.e., in flavours and sounds and art that benefited greatly and continuously not only the Americans lato sensu—remembering how the roots of slavery are intertwined with the southern countries of the continent—but Europe as well. Currently, it is not surprising that the advocacy for gun control rises from the population that had suffered by and large from being armed in the peripheries of the US, whereas those entitled to protection inside the belt cannot relate to the danger guns represent. Guns are made to protect their entitlement after all, and the system works, directly or indirectly, as guns are mainly used by outcasts to kill outcasts. The question lying beneath these grounds is how strong the mechanics of exclusion and violence crafted by Europeans centuries ago is still operating and entrapping us in cyclic violence, despite our best efforts as scientists, social engineers, and legal designers suffering together its outcomes. A scene from ‘Blackish’ where a number of African Americans refrain from helping a white baby girl lost in the elevator[21] may explain something about the torque of these mechanics. For generations, black men in the Americas were taught not to dare to look, much less to touch, white girls, and changing their disposition on it is not an easy task, and for most, an objectionable one—anyone who sees the scene played so brilliantly with the blushes of comedy will not suspect the punch in the stomach that accompanies it, as the spectator cannot escape its actuality. ‘The Green Mile’ goes deeper into the weeds to explain this. When we confront, on the one hand, the reality of Andre Johnson (Anthony Anderson) in ‘Blackish’, as taught by his ‘pops’ (Lawrence Fishburne), with, on another hand, Ted Lasso’s loveable character Sam Obisanya (Toheeb Jimoh), who is also very close to his father (uncredited in the show), but comes from Nigeria to England, concerning white women, another important point comes out to elucidate the differences on both sides of the Atlantic in how Africans and African descendants interact with gender and race combined. Andre is taught about the ‘swag’ of black males and how to refrain from wasting it on white women; whereas Sam is highly supported by all around him as the love interest of the most empowered female character in the show, Rebecca Walton (Hannah Waddingham), and winds a loving delicate sway over his peers and all over the narrative due to his affable nature. Africans and unrooted African descendants experience differently this combination of gender and race, accrued by geography, since it matters which sides of the Atlantic they may be on. These few examples add shades and textures to the epitomic dialogue between T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) and Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) in the final scenes of ‘Black Panther’, on what could be seen as the consequences of what Europe did to the globe by forcefully uprooting Africans from their natal homes. Misogyny, Eugenics, and Radical Ecologism Like in Redgrave’s painting-within-the-painting—where the dubiousness of the biblical story depicted in the picture in the wall, either of Abraham and Hagar and Ishmael or of Christ and the Adulterer, is purposedly ‘left hanging’ in juxtaposition to the paterfamilias power justification to the father to curse his progeny out of his respectable foyer—religion in Europe remains fickle towards the real problem, which has always been the persistent European ways of weaponising ideologies. The farcical blame on Christianity to justify Eurotribalism has in this light been a growing distraction among social scholars. That Judeo-Christian morality—not tradition, since this idea of an ensemble tradition was antisemitic in its base—has revamped or revived in itself in many echelons, including neo-Nazi ecologism—which certainly is astonishing—should not be concerning in itself: it is the 101 of Kant on moral and ethos. This new ‘bashing’ of religion is another form of European denial, a refusal to take responsibility for its utilisation just like any other ideology Europe has used to justify violence. European tribalism and the game-of-I-shall-pile-up-more-than-my-cousin that Europeans have been playing for centuries answers better for the global roots of evil sprawl through self-righteousness dominance. It crossed the Atlantic and remained in play. The Atlantic may be a shorter distance to cross, though, in comparison with the extent of the abyssal indifference displayed by other groups within American and European domestic terrains. Women’s rights, for instance, are not on the agenda of international migratory law. Violence against the black community is disbelieved by many, even among equally victimised groups by violence in the United States, such as migrants—Asians or Latinos alike[22]—and survivors of gender-based violence. ‘I can’t believe I am still protesting about this’[23] has been a common claim in feminist movements that decry Euro-based systems of law that debase women’s rights in both continents, and used in a variety of other manifestations, but the universality of the demands seems to stop with protest posters. The clustering and revindication of exclusion and violence by groups in their separate ways remain great adversaries of universal humanity, which should ultimately bring us all together to solve the indignities at hand. As the SNL sketch on the ‘five-hour empathy drink’[24] shows us, the fact we all hurt seems an unswallowable truth. An ocean of commonalities in the mistreatment of women in both continents, travestied of freedoms and empowerment, could be added into evidence to speak of the misappraisal of Western women’s ‘privileged’ position in the globe. Looking into some examples brought by streaming shows—our new serialised books—we see how the voices of ‘emancipated’ women in contemporary Europe are still muffled by the tesserae of Eurotribalist morality. In 30 Monedas, Elena suffers all the stereotypical pains of a Balsaquian in rural Spain, fetishised as a divorcee, ostracised, in agonising disbelief and gaslit by her village, only to be saved by the male protagonist;[25] in Britannia, which was supposed to educate us about the druidic force of women and ecologism, the characters fall into the same traps of love affairs and silliness as any teenager in Jane Austen’s novels;[26] and in Romulus, Ilia, who plays exhaustively with manipulation and fire—in the literal sense—surrenders to hysteria in ways that could not be any closer to a Fellini-an character and the Italian drama cliches imparted upon Italian females by genre cinema.[27] Everything old is new again, including misogyny. In this realm of using fictional history to describe women as these untamed forces of nature, Shadow and Bones, based on the books of Leigh Bardugo, makes an exception in speaking accurately of women’s leeway in past Judaism, which was inherited by ‘true’ Christianity, as the veneration of Mary—another casualty in the European alienation of religions—attests. Alina is the promised link to all cultures, and her willpower among the Grisha, a metaphoric group of Jewish people at the service of the Russian empire, promises to free them from slavery and falsity and bring light to the world, since she is the ‘Sun-summoner’—a reference, perhaps, to the woman clothed with the sun in Christianity. Confronting their distinct traits could help us understand better how the European specialism and skill in hating and oppressing has sprawled around the globe. What Social Sciences can make out of Art in the era of binge-watching remains to be seen. Let’s not speak falsely Enlightened by lessons like those, we are left by Art without a shred of doubt that (i) Science has been all but evasive and has tiptoed around the sheer simplicity of hate; (ii) the European haughtiness vis-à-vis the Americas, founded by their progeny, and the globe in a large spectrum of subjects such as gender bias, migration, racism, and climate is peevish, to say the least. Their internal struggle with all those pressing issues is tangible, and religion is not to blame; using a modicum of the counterfactual thinking allowed by Art, we can imagine a world where Europeans had decided to use Confucianism or Asatro as a means to spread their wings, only to realise the results would have hardly been any different. The very idea of a ‘global hierarchy of races’, albeit barbaric—another curious term born out of European Hellenic condescension—and one that should have fallen sharply down with the downfall of imperialism, remains entrenched in all those discussions, and Christianity has nothing of the sort to display. The same, unsurprisingly, is true of ‘development’, as a goal which is still measured in much the same ways as it was when European tribes fought among themselves, which then leads us to nothing but tautological havoc. It is as if “we don’t get it”. In the meantime, those who do get it can only look at one another, and can say nothing but “There are many here among us, who feel that life is but a joke, but you and I, we’ve been through that, and this is not our fate. So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late”. [1] Dylan’s lyrics, one has to note, do not fully convey the reeling effect of ineluctability, surrendering to the no-other-option but to fight within the bulk of indescribable feelings transliterated by Hendrix’s composition. [2] See Rosie Holt https://twitter.com/RosieisaHolt/status/1425361886330200066 cf. Marius Ostrowski, “More drama and reality than ever before” in Ideology-Theory-Practice, 23/8/2021. [3] Ostrowski, Marius. Ibid. [4] ‘Snirk’, a slang term defined by the Urban Dictionary as: “a facial expression combining a sneer and a smirk, appears sarcastic, condescending, and annoyed”. At https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Snirk [5] Appadurai, Arjun. “Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination” in Public Culture 12(1): 1–19. Duke University Press, 2000. [6] After all Popper was in the quest of a better world represented by an open society. Cf. Popper, Karl. In search of a better world: Lectures and essays from thirty years. Routledge, 2012. Cf. also Popper, Karl R. The open society and its enemies. Routledge, 1945. [7] See comments by Daniel Davison-Vecchione, at “Dystopia and social theory” in Ideology-Theory-Practice, 18/10/2021, on Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, as quoted translated by Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells, London: Penguin Books, 2002. [8] We use here Gleen Albrecht’s terminology, ‘solostalgia’, to describe the disconnection with the world in what can be our synesthetic experience in it, as well as with the feelings of fruition of this experience, from our reasoning of those experience, in a narrower version of what the author described as the “mismatch between our lived experience of the world, and our ability to conceptualise and comprehend it”. Cf. Albrecth, Glenn. “The age of solastalgia” in The Conversation. August 7, 2012. [9] Elizabeth Hinton describes ‘social grievances’ both as the cause for lynching Afro-Americans who were accused of transgressing determined rules, such as “speaking disrespectfully, refusing to step off the sidewalk, using profane language, using an improper title for a white person, arguing with a white man, bumping into a white woman, insulting a white woman, or other social grievances,” anything that ‘offended’ white people and challenged racial hierarchy (pp. 31–32 of Lynching Report PDF)”, as well as the social grievances hold by the black community as reason for the riots and manifestations from the 1960’s to present BLM. Cf. Hinton, Elizabeth. America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s. Liveright, 2021. [10] https://www.abc.net.au/religion/is-there-really-a-judeo-christian-tradition/10810554 [11] Hinton. Idem, particularly Chapter 8 ‘The System’. [12] https://upstanderproject.org/firstlight/doctrine [13] Deleuze, Gilles. La logique du sense. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1969. [14] Here we refer to Popperian concepts and notions again, principally to how he explains the nature of scientific discovery at The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge, 1959. [15] Brother Day (Lee Pace) commend his younger clone, Brother Dawn, for looking into an artifact brought by diplomats to the Imperials as a gift and the lack of a certain metal in it as a metaphor to that people need for that specific metal, therefore, an elegant request to the Galactical Empire for trade agreements, thus leading to the phrase: ‘Art is politics’ sweeter tongue’. It is not a directions quotation from the original work of Asimov in the Foundation trilogy; whether is an implication stemming from any other of his writings is unknown. [16] ‘Virtue signaling’ and ‘virtue vesting’ have been described in a variety of ways, but ‘Mr. President’ in Midnight Gospel’s pilot shed some light on the notions assuring they are rather democratic: centrists, leftists, rightists, all can use them indistinctly, since the fear of being disliked seems to be the only real motivation behind pro and cons positions, accordingly with Daren Duncan. The dialogue between Mr. President (who has no party) with the Interviewer: “Interviewer: - I know you've gotta be ncredibly busy right now with the zombie apocalypse happening around you./ Mr. President: - Yeah, zombies... I really don't wanna talk about zombies./ Interviewer: - Okay. What about the marijuana protesters?/Mr. President” -Those assholes? -Yeah. - First of all, people don't understand my point of view. - They think somehow I'm anti-pot or anti-legalisation./ Interviewer: - Right./ Mr. President: -I'm not actually "pro" either. - I'm pro human liberty, I'm pro the American system, pro letting people determine their laws./ Interviewer: -Right./ Mr. President: -I don't think this is... -If I had to... -[sniffs] ...have a... You know, if somebody pressed my face to the mirror and said,"Is it gonna be good or bad?" I think it might end up being kinda not so good for people…” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kQWAqjFJS0&t=45s [17] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mVbdjec0pA [18] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1Pl8CzNzCw [19] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NPBIwQyPWE [20] Anderson, Jem; Kelly, Justin; Mckeon, Brian. “How we kill each other? FBI Murder Reports, 1980-2014” In Applied Statistics and Visualization for Analytics. George Mason University, Spring 2017. [21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=daJZU5plRhs [22] Yellow Horse AJ, Kuo K, Seaton EK, Vargas ED. Asian Americans’ Indifference to Black Lives Matter: The Role of Nativity, Belonging and Acknowledgment of Anti-Black Racism. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(5):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168 [23] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13603124.2019.1623917?journalCode=tedl20 [24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OP0H0j4pCOg [25] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdmMoAuD-GY [26] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JbFo7r_41E [27] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8wQNZ1N3T by Marta Lorimer

Far-right parties are frequently, and not without cause, painted as fervent Eurosceptics, or even ‘Europhobes’. Ideologically nativist, and usually placed at the margins of the political system, these parties appear as almost naturally inclined to oppose a supranational construction generally supported by mainstream actors. But how accurate is this narrative? Are far-right parties really naturally ‘Eurosceptic’, and what does it even mean to be ‘Eurosceptic’?

A cursory look at the history of the far right should give one reason for pause. For starters, several of the parties that are today seen as Europhobes started off as pro-EU and have also generally benefitted enormously from the EU’s existence. Take the French Rassemblement National (RN, previously, Front National) as an example. In the 1980s, long before Marine Le Pen spoke about Frexit, her father made his first appearance on the national scene in European elections and insisted that Europe ‘shall be imperial, or shall not be’.[1] More broadly, knowing how these parties feel about the EU tells us very little about what they think about Europe beyond the narrowly construed project of the EU. Indeed, their language is replete with references to a European (Christian) civilisation worth protecting, claims seemingly at odds with the rabid opposition by many of them to the European Union. In my research on the relation between the far right and Europe, I attempt to make sense of these tensions by analysing how far-right parties conceive of Europe through ideological lenses, and the effects that approaching Europe in a certain way has. I advance two key arguments: first, I hold that the depiction of far-right parties as ‘naturally’ Eurosceptic is misleading. Second, I posit that these parties’ positions on European integration served the broader purpose of legitimising them by making them appear more palatable to a general public. These claims are developed empirically through the in-depth study of how the Italian Social Movement/Alleanza Nazionale (MSI/AN) in Italy and the Rassemblement National in France integrated Europe in their ideological frames over the period 1978-2017, and to what effects. What do they talk about when they talk about Europe? Let us start with the first of the two claims, namely, that the depiction of far-right parties as ‘naturally’ Eurosceptic is misleading. To develop this point, it is pertinent to take a step back and ask first ‘but what do far-right parties talk about when they talk about Europe’? One way to address this question is to analyse the concepts that these parties commonly associate with Europe in their party literature.[2] In the MSI/AN and RN’s ideology, three in particular stand out: the concepts of identity, liberty, and threat. In each of these key concepts, the parties express an ambivalent view of Europe at odds with the term ‘Eurosceptic.’ The concept of identity refers to a category of identification that allows groups to define who they are, through considerations of the positive (and negative) aspects of the group they belong to. The MSI/AN and RN rely on this concept to define Europe as a distinct civilisation. The MSI, for example, spoke in favour of European unity conscious of the ‘community of interests and destinies, of history, of civilisation, of tradition among Europeans’,[3] while Jean-Marie Le Pen spoke of Europe as ‘A historic, geographic, cultural, economic, and social ensemble. It is an entity destined for action’.[4] This understanding is not one that is strictly time-bound, and as late as 2017, Marine Le Pen could affirm that for her party ‘Europe is a culture, it’s a civilisation with its values, its codes, its great men, its accomplishments its masterpieces […] Europe is a series of peoples whose respective identities exhale the fecund diversity of the continent’.[5] Importantly, both the MSI/AN and RN consider themselves as part of this civilisation and view it as compatible with their national identity. As the MSI/AN put it, ‘Individuality (in this case national) and community (in this case European) are not in opposition but in reciprocal integration and vivification’.[6] In addition to approaching Europe through the prism of identity, the MSI/AN and RN also rely on the concept of liberty to define it. Liberty, as it is understood in their discourse, is an essential attribute of the nation and corresponds to central principles of autonomy, self-rule, and power in the external realm. It is also understood as a collective term: the bearer of ‘liberty’ is not the individual, but the nation intended as a holistic community. The relation between liberty and Europe, however, changes significantly through time. In the 1980s, the RN and the MSI spoke of Europe as a space in need of ‘liberty’ in face of the ‘twin imperialisms’ of the USA and the USSR. This was also associated with the need to re-establish Europe as an international power which could not only defend its nations, but also, reinforce their global influence. From the end of the 1980s, however, and particularly for the RN, ‘liberty’ shifted from being an attribute of Europe to being an endangered part of the national heritage. The introduction of the Single European Act and the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty contributed significantly to this shift (although they are not the only factors).[7] These treaties did little to make the EU into a strong international actor, as they privileged economic integration over integration in matters of foreign policy and defence. Furthermore, by setting the EU on an increasingly federal path, they were at odds with the RN’s view that European unity should happen in the form of a vaguely-defined (but clearly confederal) ‘Europe of the Nations’. As a result, the RN starts speaking increasingly about ‘sovereignty’ as a ‘collective form of liberty’ endangered by the EU. The final concept that the parties draw upon to define Europe is that of threat, with Europe presented as a community endangered by a variety of threats such as the USSR in the 1970s and 1980s, the USA in the 1980s and 1990s, and decline and migration throughout. While the nature of threats varies across parties and across time, Europe and its nations always appear to be threatened by some evil force that requires swift intervention. As with liberty, however, the relation between Europe and threat changes over time: whereas in the 1980s, Europe was mainly an endangered community (and indeed, a potential source of protection from external threats), since the 1990s, Europe in the shape of the EU has become a threat in and of itself. This is particularly true for the RN, which since the 1990s has identified globalisation as a growing threat, and the EU as its vector. Europe, in this sense, went from being an instrument which could protect from ‘others’, to an ‘other’ which could facilitate the demise of nation states by facilitating the instauration of a new, globalised world order. As will have become evident, the MSI/AN and RN’s approach to Europe shows more nuance than the term ‘Eurosceptic’ fully captures, and ‘Euro-ambivalence’ seems to be a better descriptor of their positions. Whereas the EU has frequently been an enemy (although more so for the RN than for the MSI/AN), this was not always the case, and ‘Europe’ remained a positively valued concept throughout. This ambivalence is grounded in three elements: First, political ideologies are notoriously flexible: while one might expect some degree of continuity, they are also deeply contextual and can evolve over time and depending on historical and national circumstances. In this sense, ambivalence emerges both synchronically across countries and diachronically over time depending on contextual changes. Second, the European Union is a complex construction in constant evolution. Whereas it started as a small economic union of Western European countries, it has evolved into a deeply political construction encompassing a large part of the European continent. Far-right parties’ ambivalence therefore partially depends on which aspect of the EU they are looking at, and at what phase of its historical development. Finally, for as much as the EU tries to equate the two, ‘Europe’ and the EU remain two different constructions. The EU is but one embodiment of the idea of Europe, and the far right’s ambivalence about Europe also derives from swearing allegiance to ‘Europe’ while rejecting the political construction of the EU. As the party statutes of the far right ‘Identity and Democracy’ group in the European Parliament show, far-right parties are willing to acknowledge that Europeans share a common ‘Greek-Roman and Christian heritage’ and consider that this heritage creates the bases for ‘voluntary cooperation between sovereign European nations.’ However, they also reject the EU and its attempts to become ‘a European superstate’.[8] Summing up, while today we tend to see far-right parties as Eurosceptic, this was not always the case, and neither does the term fully capture the complexity of their positions. Ambivalence about Europe is an important part of the far right’s approach to Europe, and can help us understand why far-right parties can collaborate transnationally in the name of ‘another Europe’ different from the EU. Europe as ideological resource In addition to being ambivalent about Europe, far-right parties also have a marked tendency to benefit from it. The EU has, in fact, provided these parties with symbolic and material resources that have helped them become established actors. Electorally, the proportional system of representation employed in EU elections made it easier for far-right parties to gain representation. This has also come with a gain in resources which could be used to improve their standing in domestic elections.[9] Far-right parties have also sought to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the EU, for example by employing alliances in the European Parliament to enhance legitimacy at home.[10] One might ask how speaking about Europe in a certain way may have helped the far right. A plausible answer to this question is that Europe presented an ideological resource for far-right parties looking for legitimation because it allowed them to reorient their ideology in a more acceptable fashion and speak both to their traditional electorate and to new supporters.[11] An ideological resource, as I define it, is a device that offers political parties an opportunity to revise and reframe their political message in a more appealing way. Europe is one such resource. As a relatively new political issue, and one which has no clear ideological answer, it leaves parties, including far-right ones, with some leeway in determining the position they adopt. As such, it makes it possible for them to craft a position that is appealing to their traditional voters and to new voters alike. In addition, the divisiveness of European integration can benefit far-right parties because it makes dissent more acceptable. Because European integration has divided political parties and electorates alike, it is a topic on which disagreement is acceptable and where it may be easier for parties to present a more widely appealing political message. To illustrate this argument, it is worth looking at two specific discourses employed by the RN in association with the previously discussed concepts of identity and liberty: its claim to be ‘pro-Europe and anti-EU’ and its growing focus on questions of sovereignty, autonomy, and independence. As discussed earlier, the RN has since the 1980s claimed to be ‘pro-European’, however, since the end of the 1980s it has also increasingly pitted its support for Europe against the European Union. For example, a 1991 party guide draws a distinction between ‘two Europes’ holding that ‘The first conception is that of a cosmopolitan or globalist Europe, the second is that of a Europe understood as a community of civilisation. The first one destroys the nations, the second one ensures their survival. The first one is an accelerator of decline, the second an instrument of renaissance. The first is the conception of the Brussels technocrats and of establishment politicians, the second is our conception.’[12] More recently, Marine Le Pen has claimed that ‘even though we are resolutely opposed to the European Union, we are resolutely European, I’d go as far as saying that it is because we are European that we are opposed to the European Union’.[13] The claim to be pro-Europe but anti-EU serves the dual purpose of attracting new voters by presenting them a ‘softer’ and less nationalist face, all the while maintaining the old ones by relying on the notion of a closed identity that is key to traditional RN discourse. Speaking of Europe in these terms, then, makes it possible for the RN to construct a more legitimate image, without, however, losing the support of its existing electoral base. The RN’s reliance on ideas of sovereignty, independence, and autonomy to criticise the EU serves a similar purpose. When the party says things like ‘A nation’s sovereignty is its ability to take decisions freely and for itself. It refers then to the notions of independence and exercise of political power by a legitimate government. The entire history of the European construction consists of depriving States of their sovereignty’,[14] it is both speaking about elements that are perfectly compatible with its own nationalist ideology, and drawing on more common discourses about the nation that may carry broader appeal. These critiques also resonate with critiques of the EU presented by actors with no association with the far right, an element which may provide them with an additional ‘ring of truth’. In sum, while opposition to European integration is frequently presented as a marker of marginalisation for parties, when well phrased it can in fact function as a powerful tool for legitimation that far-right parties can seize upon. Where to for the far right and Europe? Simplification is often necessary in the social sciences; however, it is worth remembering that even seemingly straightforward associations can be more complicated than one thinks. The link between far-right ideology and opposition to ‘Europe’ is one of these associations that seems intuitive, but which conceals a more variegated picture made of a history of support for European integration, attachment to a different ‘Europe’, and a penchant for benefitting from a project it explicitly rejects. Understanding and appreciating the ‘Euro-ambivalent’ nature of far-right parties can help make sense of some recent phenomena such as the transnational collaboration of nationalists. Because many of these parties share a common vision of Europe, they can leverage it to justify their collaboration on an international scale as part of a project to defend Europe from the EU.[15] They have also been able to collaborate because they found cooperation beneficial: namely, it served to portray them as a unified and growing movement, carrying ever greater political weight and forming the main axis of opposition to the cosmopolitan elites. Crucially, however, one should not assume that a far-right takeover or destruction of the EU institutions is in the making or ever likely to happen. On the one hand, while far-right parties do benefit from some ideological flexibility, the nation and the national interest remain their guiding principles. Thus, while the far right may be able to argue that they are both nationalists and Europeans, in case of conflict, it is unlikely that their commitment to Europe will ever trump the nation. In the improbable event that far-right parties did engineer a takeover of EU institutions, it is also doubtful that they would actively seek to dismantle them. Europe, after all, has its uses, and it is likely that they will be willing to take advantage of some of them. More likely, the far right would try to transform the EU into something more compatible with their own worldview; however, what this ‘Europe of the Nations’ would look like, or how it would function, remains mostly unclear. What is more problematic for the EU in the short term is that much of the far right’s criticism contests core assumptions about the EU institutions, and runs counter some of the solutions brought forward to tackle its own legitimacy deficit. For example, the centrality of the concept of Identity to far-right parties’ definition of Europe raises questions about the feasibility of promoting a ‘European identity’ as a solution to the EU’s legitimacy issues. At the same time, the far right’s claims to be ‘pro-Europe but anti EU’ bring to the fore the contestedness of the concept of Europe, and create a counter-narrative of Europe which questions the very premise that the EU is the embodiment of Europe. Reopening that equation to contestation removes one of the EU’s legitimising narratives, suggesting that the way ahead for the EU will remain paved with opposition. In sum, even if far-right parties may not be able to coalesce to dismantle the EU or orchestrate a takeover of its institutions from the inside, they can still rock it to its very core. [1] J.-M. Le Pen, J. Brissaud, & Groupe des Droites européennes. (1989). Europe: discours et interventions, 1984-1989 (Issue Book, Whole). Groupe des Droites européennes. [2] M. Lorimer. (2019). Europe from the far right: Europe in the ideology of the Front National and Movimento Sociale Italiano/Alleanza Nazionale (1978-2017). London School of Economics and Political Science. [3] Movimento Sociale Italiano. (1980). Il Msi-Dn dalla a alla zeta : principii programmatici, politici e dottrinari esposti da Cesare Mantovani, con presentazione del segretario nazionale Giorgio Almirante . Movimento sociale italiano-Destra nazionale, Ufficio propaganda. [4] J.-M. Le Pen. (1984). Les Français d’abord. Carrère - Michel Lafon. [5] M. Le Pen. (2017). Discours de Marine Le Pen à la journée des élus FN au Futuroscope de Poitiers.. [6] Movimento Sociale Italiano, 1980. [7] M. Lorimer. (forthcoming) ‘The Rassemblement National and European Integration,’ in Berti, F. and Sondel-Cedarmas, J., ‘The Right-Wing Critique of Europe: Nationalist, Sovereignist and Right-Wing Populist Attitudes to the EU’, London: Routledge. [8] Identity and Democracy. (2019). Statutes of the Identity and Democracy Group in the Europeaan Parliament. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/kantodev/pages/102/attachments/original/1582196570/EN_Statutes_of_the_ID_Group.pdf?1582196570; M. Lorimer. (2020b). What do they talk about when they talk about Europe? Euro-ambivalence in far right ideology. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(11), 2016–2033. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1807035. [9] E. Reungoat. (2014). Mobiliser l’Europe dans la compétition nationale. La fabrique de l’européanisation du Front national. Politique européenne, 43(1), 120–162. https://doi.org/10.3917/poeu.043.0120; J. Schulte-Cloos. (2018). Do European Parliament elections foster challenger parties’ success on the national level? European Union Politics, 19(3), 408–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518773486 [10] D. McDonnell & A. Werner. (2019). International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament. Hurst; N. Startin. (2010). Where to for the Radical Right in the European Parliament? The Rise and Fall of Transnational Political Cooperation. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2010.524402. [11] M. Lorimer. (2020a). Europe as ideological resource: the case of the Rassemblement National. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(9), 1388–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1754885. [12] Front National. (1991). Militer Au Front. Editions Nationales. [13] M. Le Pen, 2017. [14] Front National. (2004). Programme pour les élections européennes de 2004. [15] A point perceptively made by McDonnell and Werner, 2019 as well. by Fabio Wolkenstein

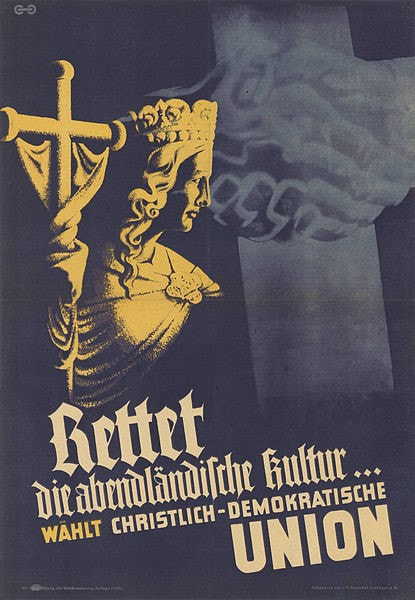

One of the more interesting political developments in contemporary Europe is the migration of the language that has originally been used to describe what Europe is. This language has migrated from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, who were committed to unifying Europe and creating a more humane political order on the continent, to the speeches and campaigns of nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. The idea of “Christian Europe” Consider to start with the notion of Abendland, which may be translated as “occident” or, more accurately, “Christian West.” In the immediate post-war era, the term had been a shorthand for Europe in the predominantly Catholic Christian-democratic milieu whose political representatives played a central role in the post-war unification of Europe; indeed, the “founding fathers” of European integration, Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi, were convinced that – as De Gasperi put it in a 1954 speech – “Christianity lies at the origin of … European civilisation.”[1] By Christianity was primarily meant a common European cultural heritage. De Gasperi, an Italian educated in Vienna around 1900, whose first political job was in the Imperial Council of Austria-Hungary, spoke of a “shared ethical vision that fosters the inviolability and responsibility of the human person with its ferment of evangelic brotherhood, its cult of law inherited from the ancients, its cult of beauty refined through the centuries, and its will for truth and justice sharpened by an experience stretching over more than a thousand years.”[2] All of this, many Christian Democratic leaders thought, demarcates Europe from the superficial consumerism of the United States – however welcome the help of the American allies was after WW2 – and, even more importantly, the materialist totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. Europe is culturally distinctive, and that distinctiveness must be affirmed and preserved to unite the continent at avoid a renewed descent into chaos. This image of Europe figured prominently in the Christian Democrats’ early election campaigns. In 1946, a campaign poster of the newly-founded Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) featured the slogan “Rettet die abendländische Kultur” – “Save abendländische culture.” The poster boasts a bright depiction of the allegorical figure Ecclesia from Bamberg Cathedral, which is meant to represent the superiority of the Church. And Ecclesia faces the logo of the SED, the East German Communist Party, which was founded the same year. The message was clear: a democracy “rooted in the Christian-abendländisch worldview, in Christian natural law, in the principles of Christian ethics,” as Adenauer himself put it in a famous speech at the University of Cologne, had to be cultivated and defended against so-called “materialist” worldviews that represented nothing less than the negation of Christian principles, and by extension the negation of moral truth. In Adenauer’s view, Europe was “only possible” if the different peoples of Europe came together to contribute not only economically to recovering from the war, but also culturally to “abendländisch thinking, poetry.”[3]

This idea of Europe also resonated with General Charles De Gaulle, who served as the first French president after the founding of the Fifth Republic, and who became a natural ally for Adenauer and German Catholic Christian Democrats. De Gaulle certainly had a more nation-centric vision of European integration than Adenauer, and he resisted the idea that supranational institutions should play a central role in the integration processes – but he likewise envisioned a concert of European peoples that shared a common Christian civilisation. These nations should, in De Gaulle’s words, become “an extension of each other,” and their shared cultural roots should facilitate this process. The Italian historian Rosario Forlenza aptly summarised De Gaulle’s views on Europe as follows: “When le général famously spoke of a Europe ‘from the Atlantic to the Urals’ he was in fact conjuring up, quite in line with the Abendland tradition, a continental western European bloc based on a Franco-German entente that could stand on its own both militarily and politically: a Europe independent from the United States and Russia.”[4] In his memoirs, moreover, De Gaulle asserted that the European nations have “the same Christian origins and the same way of life, linked to one another since time immemorial by countless ties of thought, art, science, politics and trade.”[5] No wonder many Christian Democrats saw Gaullism as “a kind of Christian Democracy without Christ.”[6] European integration from shared culture to markets However, those political leaders who conceived Europe as a cultural entity were gradually disappearing. De Gasperi died already in 1954, Adenauer died in 1967, and De Gaulle resigned his presidency in 1969 and died one year later. Robert Schuman, the other famous Christian Democratic “founding father,” who has been put on the path to sainthood by Pope Francis in June 2021, died in 1963. Replacing them were younger and more pragmatic political leaders, many of whom believed that free trade was better able to bring the nations of Europe closer to each other than shared cultural roots.[7] Culture was not considered irrelevant, to be sure – this is why hardly anyone considered admitting a Muslim country like Turkey to the European Communities. But the idea of a Christian Europe whose member countries shared a distinctive heritage, which performed the important function of unifying an earlier generation of centre-right politicians, was gradually superseded by the much less concrete notion of “freedom” as a sort of telos of European integration.[8] Already in the late 1970s, powerful conservative leaders such as Helmut Kohl and Margaret Thatcher converged on the vision that European integration should secure freedom. “Freedom instead of socialism” was the CDU’s 1976 election slogan, which was quite different from “Save abendländische culture” in 1946. Socialism remained the primary enemy – but it should be fought with free markets, not Christian ethics and natural law, as Adenauer believed. Importantly, foregrounding the notion of freedom and de-emphasising thick conceptions of a shared European culture also facilitated the gradual expansion of the pan-European network of conservative parties from the mid-1970s onwards. Transnationally-minded Realpolitiker like Kohl realised already in the mid-1970s that integrating “Christian democratic and conservative traditions and parties” from non-Catholic countries into the European People’s Party and related transnational organisations was crucial to avoid political marginalisation in the constantly expanding European Communities.[9] And many new potential allies, perhaps most notably Scandinavian conservative parties who obviously had no Catholic pedigree, would have shrunk from the idea of joining a Christian Abendland modelled in the image of Charlemagne’s empire. The re-emergence of the language of Christian Europe At any rate, while the language of a Europe defined by shared culture gradually disappeared from the vocabulary of centre-right politicians, decades later it re-appeared elsewhere. It was adopted by political actors who are often categorised as “right-wing populists” – more accurately, we might call them nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives. These sorts of political movements have discovered and re-purposed the culturalist narrative of a “Christian Europe.” In the German-speaking world, even the notion of Abendland made a comeback on the right fringes. The Alternative für Deutschland (or AfD), Germany’s moderately successful hard-right party, commits itself in its main party manifesto to the “preservation” of “abendländisch Christian culture.”[10] The closely related anti-immigrant movement PEGIDA even has Abendland in its name: the acronym stands for “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamicisation of the Abendland.” The Austrian Freedom Party, one of the more long-standing ultraconservative nationalist parties in Europe, used the Slogan “Abendland in Christenhand,” meaning “Abendland in the hands of Christians” in the 2009 European Elections. Even more striking are the increasing appeals to the idea of Christian Europe that resound in Central and Eastern Europe. The political imaginaries of the likes of Viktor Orbán – the pugnacious Hungarian prime minister who has transformed Hungary into an “illiberal democracy” – and Jarosław Kaczyński and his Polish Law and Justice party, are defined by an understanding of Europe as a culturally Christian sphere. And they claim to preserve and defend this Europe, especially against the superficial, culturally corrosive social liberalism of the West, which they consider a major threat to its shared values and traditions. Orbán even seeks to link the notion of Christian Europe to the ideological tradition of Christian Democracy. Not only has he repeatedly called for a “Christian Democratic renaissance” that should involve a return to the values and ideas of the post-war era.[11] In February 2020, when the European People’s Party – the European alliance of Christian Democratic parties – seemed increasingly willing to expel Orbán’s party Fidesz due to the undemocratic developments in Hungary, he even drafted a three-page memorandum for the European Christian Democrats. In this memorandum, a most remarkable document for anyone interested in political ideologies, he listed all the sort of things that Christian Democrats “originally” stood for – from being “anti-communist” and “pro-subsidiarity” to being “committed representatives … of the Christian family model and the matrimony of one man and one woman.” However, he added, “We have created an impression that we are afraid to declare and openly accept who we are and what we want, as if we were afraid of losing our share of governmental authority because of ourselves.”[12] To save itself, and to save Europe, a return to the ideological roots of Christian Democracy is needed; or so Orbán argued. In sum, the language of Europe as a thick cultural community, the idea of a Christian Europe, and indeed some core elements of the ideology of Christian Democracy itself – all this has migrated to other sectors of the political spectrum and to Eastern Europe. Ideas and concepts that after WWII were part of the centre-right’s ideological repertoire are now used by nativists and ultraconservative nationalists, and used in order to justify their exclusivist Christian identity politics.[13] Note that the Eastern European parties and politicians who today reach for the narrative of Christian Europe stand for a broader backlash against the previously-hegemonic, unequivocally market-liberal and pro-Western forces that made many Western European centre-right leaders enthusiastically support Eastern Enlargement in the early 2000s. For the Polish Law and Justice party not only rejects liberal views about same sex-marriage, abortion, etc.; several of its redistributive policies also mark “a rupture with neoliberal orthodoxy,” and thus a departure from the policies of the business-friendly, pro-EU Civic Platform government of Donald Tusk, which Kaczyński’s party replaced in 2015.[14] In Orbán’s Hungary, free-market policies have largely remained in place – especially when Orbán and his cronies profited from them – yet the recent “renationalisation of the pension system [and] significantly increased spending on active labour market policies … point towards an increasing … role of the state in social protection.”[15] Understanding the migration of language One interesting interpretation of this development frames it in terms of a revolt of Eastern – and indeed Western – European nativists and nationalists against a perceived imperative to be culturally liberal and anti-nationalist. Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes perceptively note that “[t]he ultimate revenge of the Central and East European populists against Western liberalism is not merely to reject the ‘imitation imperative’, but to invert it. We are the real Europeans, Orbán and Kaczyński claim, and if the West wants to save itself, it will have to imitate the East.”[16] While there is much to be learned from this analysis, another reading of the eastward and rightward migration of culturalist understandings of Europe is available. This starts from the observation that talking about Europe as a geographical space defined by a deeply rooted common culture implies talking also about where Europe ends, where its cultural borders lie. Recall that the Europe envisaged by the Christian Democratic “founding fathers” and by De Gaulle was a much smaller, more limited entity than today’s European Union with its 27 member states. They believed, for example, that there were profound cultural differences between the abendländisch, predominantly Catholic Europe and Protestant Britain and Scandinavia. De Gaulle was in fact fervently opposed to admitting Britain to the European Communities and famously vetoed Britain’s applications to join in 1963 and 1967. If talking about Europe in cultural terms necessarily involves talking about cultural boundaries, then it is perhaps not surprising that today’s nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives came to endorse a culturalist understanding of Europe. After all, these are virtually the only political actors who indulge in talking about borders and attribute utmost importance to problematising and politicising cultural difference. Seen in this light, it is only natural that the once-innocuous notion that Europe has, as it were, “cultural borders” finds a home with them. Revisiting the question of European culture One need not endorse the political projects of Viktor Orbán, Jarosław Kaczyński and their allies to acknowledge that the questions they confront us with merit attention. What is Europe, if it is an entity defined by shared culture? And, by extension, where does Europe end? Not only those who simply do not want to leave it up to nativists, nationalists and ultraconservatives to define what Europe is, culturally speaking, will need to ponder these questions. Where Europe ends is also a highly pertinent issue in current European geopolitics, and interestingly, it seems as though key EU figures are gradually converging on a position that structurally resembles a view that was prominent on the centre-right in the post-war era – without linking it to narratives about shared culture. Indeed, with the Von der Leyen Commission’s commitment to “strategic autonomy” and the objective to ascertain European sovereignty over China, the original Christian Democratic and Gaullist theme of Europe as independent “third” global power has returned with a vengeance – just that independence today means independence from the United States and China, not the United States and Soviet Russia (though Russia remains a menacing presence).[17] However, whereas De Gaulle and Christian Democratic “Gaullists” saw Europe’s Christian origins and a shared way of life as the backbone of geopolitical autonomy, the President of the Commission limits herself to mentioning the “unique single market and social market economy, a position as the world’s first trading superpower and the world’s second currency” as the sort of things that make Europe distinctive.[18] Much like earlier pragmatically-minded politicians, then, von der Leyen mostly speaks the language of markets – and of moral universalism: “We must always continue to call out human rights abuses,” she routinely insists with an eye to China.[19] But it is doubtful whether human rights talk or free market ideology are sufficient to render plausible claims to “strategic autonomy.” Being by definition boundary-insensitive and global in outlook, they are little able to furnish a convincing argument for why Europe should be more autonomous.[20] Perhaps the notion of “strategic autonomy” is actually much more about a shared European “way of life” than present EU leaders, unlike their post-war predecessors, are willing to admit. Why else would von der Leyen also want to appoint a “vice president for protecting our European way of life,” whilst describing China as “systemic rival” and even cautiously expressing uncertainty about the ally-credentials of post-Trump America? Here, the twin questions of European culture and where Europe ends, come into view again. And it seems by all means worthwhile to speak more about that – without adopting the narrow and exclusionary narratives of Orbán and Kaczyński or wishing for a return to post-war Christian Democracy or Gaullism. [1] Cited in Rosario Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland: Christian Democracy and the Idea of Europe after the Second World War’, Contemporary European History 26(2) (2017), 269. [2] Ibid. [3] Konrad Adenauer, (1946) Rede in der Aula der Universität zu Köln, 24 March 1946. Available at https://www.konrad-adenauer.de/quellen/reden/1946-03-24-uni-koeln, accessed 15 May 2020. [4] Forlenza, ‘The Politics of the Abendland’, 270. [5] Charles de Gaulle, Memoirs of Hope: Renewal and Endeavor (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971), 171. [6] Ronald J. Granieri, ‘Politics in C Minor: The CDU/CSU between Germany and Europe since the Secular Sixties’, Central European History 42(1) (2009), 18. [7] Josef Hien and Fabio Wolkenstein, ‘Where Does Europe End? Christian Democracy and the Expansion of Europe’, Journal of Common Market Studies (forthcoming). [8] Martin Steber, Die Hüter der Begriffe: Politische Sprachen des Konservativen in Großbritannien und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1945-1980 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), 410-422. [9] Wolfram Kaiser, Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 316. [10] Alternative für Deutschland, Programm für Deutschland (2016) Available at https://cdn.afd.tools/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2018/01/Programm_AfD_Druck_Online_190118.pdf, accessed 16 September 2020. [11] Cabinet Office of the Hungarian Prime Minister, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s speech at a conference held in memory of Helmut Kohl (16 June 2018), Available at: http://www.miniszterelnok.hu/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-speech-at-a-conference-held-in-memory-of-helmut-kohl/, accessed 10 June 2020. [12] Fidesz, Memorandum on the State of the European People’s Party, February 2020. [13] Olivier Roy, Is Europe Christian? (London: Hurst, 2019), 118-214. [14] Gavin Rae, ‘In the Polish Mirror’, New Left Review 124 (July/Aug 2020), 99. [15] Dorothee Bohle and Béla Greskovits, ‘Politicising embedded neoliberalism: continuity and change in Hungary’s development model’, West European Politics, 1072. [16] Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes, ‘Imitation and its Discontents’, Journal of Democracy 29(3) (2018), 127. [17] Jolyon Howorth, Europe and Biden: Towards a New Transatlantic Pact? (Brussels: Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, 2021). [18] Speech by President von der Leyen at the EU Ambassadors’ Conference 2020, 10 November 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_2064, accessed 22 June 2021. [19] Ibid. [20] As Quinn Slobodian convincingly argues, free market ideology ultimately seeks to achieve a global market with minimal governmental regulations, see Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). by Rieke Trimçev, Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, and Friedemann Pestel

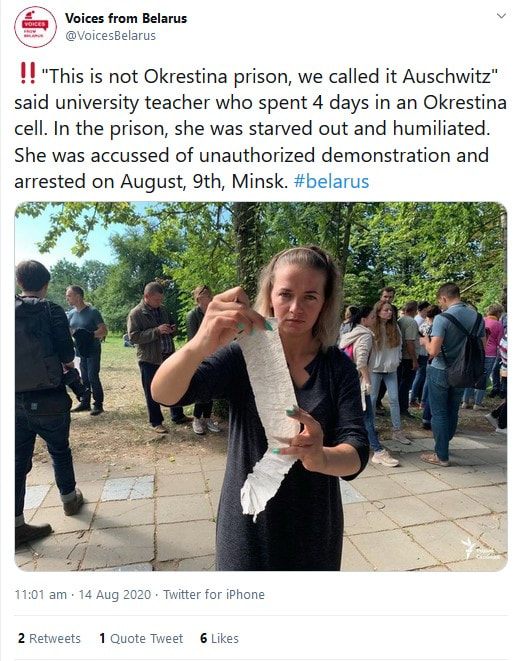

During the upheaval against Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus after the contested presidential election in August 2020, the idea of ‘Europe’ has often been invoked. These invocations might be surprising, given that Belarusians themselves have shunned explicit references to the EU and that EU flags were absent on the country’s streets. Instead, a rhetorical call to Europe has served to amplify demands for the support of Belarusian society and direct Europe’s attention to a country long-neglected by the international community. Lithuania’s former foreign secretary stated on Twitter: “The 21st century. The heart of Europe – Belarus. A criminal gang a.k.a. ‘Police Department of Fighting Organized Crime’ terrorizing Belarusians who have been peacefully demanding freedom and democracy for already 80 consecutive days. Shame!” Designating a particular region as “the heart of Europe” is a popular rhetorical device, acting as a way to call for attention. During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Margaret Thatcher used the metaphor to denounce the E.C.’s failure to prevent the mass killings in Bosnia: “this is happening in the heart of Europe […] It should be within Europe’s sphere of conscience.” The force of this phrasing defies geographical reality and lies in elevating specific values and principles as central to the idea of Europe. Europe’s political activity should live up to these values, simply to protect a vital part of its body. Through this formula, places like Belarus or Bosnia become part of a shared mental map, understood as a “spatialisation of meaning [that] dwells latently in the minds of individuals or groups of people.”[1] Another look at the rhetoric of the Belarusian protests indicates that shared representations of the past and the language of memory are particularly powerful tools in spatialising meaning and increasing the visibility of regional events for a transnational audience. All these tweets and pictures compare the Okrestina Detention Centre in Minsk, where many of the protesters were interned, to the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. Leaving aside the question of whether such comparisons are appropriate, their implication for protesters is clear: “The heart of Europe” is where Europe’s founding norm of “Never again!” is at risk.

The spatialised communication of normative arguments are at the core of our ongoing research project on the contested languages of European memory—“Europe’s Europes” if you will. It is informed by a larger qualitative study, in which we study public ideas of Europe through the prism of representations of the past and the language of memory. Examining press discourse in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2018, we have reconstructed several entrenched mental maps of Europe, which differ according to regional perspectives, ideological stances or historical trajectories. Some of these imaginaries—“Europe’s Europes”—complement each other, while others stand in open or implicit contradiction and provoke conflicts over the mental geography of Europe. To say that they are “entrenched” mental maps means that they are deeply rooted in everyday thought-behaviour and help to make sense of today’s political challenges. It is here that the language of memory, whose importance in forming shared senses of identity has long been noted, shows its ideological pertinence even beyond debates over memory politics strictly speaking.[2] Understanding these mental maps allows us to better seize discursive deadlocks, but also to identify missed encounters in debating in, over and with Europe. Islands of consensus The metaphor of the “heart of Europe” pictures Europe as a body whose different parts naturally work together to assure the functioning of a holistic “community of values”. While this metaphor might sound unsurprising, it turns out to be a concept that has a limited discursive reach, and is of limited agency when it comes to everyday political debates beyond grandiose speeches. In our study, we found that Europe is predominantly understood as a contested idea. Most of the deep-rooted mental maps spatialise this contestation through imaginary borders, both internal and external. Against the predominance of these fractured mental maps, ideas of Europe as a consensual community of values appear as “islands of consensus” of limited discursive reach. Between 2004 and 2018, one such “island of consensus” structured significant parts of the Italian press discourse, where Europe was pictured as a continent united through a canone occidentale, embracing Antiquity, Judaeo-Christian roots, Enlightenment, Liberalism, and other historical cornerstones with a positive connotation. This idea of a European canon also occurs in other national discourses but is more partisan. Especially in times of crisis, speaking from within a community of values has allowed for a clear yardstick of judgment. For example, the failure to set up a joint accommodation system for migrants in 2015, from the viewpoint of this mental map, appeared to betray European memory—a memory which had claimed a humanitarian impetus when boatpeople had fled from communism in the 1970s and 1980s: “On the issue of immigration, the Europe of the single currency and strengthened political governance seems less cohesive and less aware than Europe at the time of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War. The memory of the new Europeans and the new ruling classes seems indifferent to recent history.”[3] Yet, the moral self-confidence of dwellers of an island of consensus comes at some cost. From the perspective of an island of consensus, conflicts appear as a misunderstanding that could be solved by proper integration, inclusive of a European memory. However, this perspective remained largely confined to Italy and found little echo in other discursive spheres. Frictions between ‘East’ and ‘West’ A particularly prominent way of spatialising the meaning of Europe revolves around an East-West divide. While it is prominent both in ‘old Europe’ and those post-communist countries that joined the EU in 2004, it must be understood as the junction of two different, and in fact competing mental mappings. For France and Germany, ‘Eastern Europe’ largely represents a mnemonic terrain on which, after 1945, the communist regimes froze the memories of World War 2 and the Holocaust, and which still today rejects communist rule as an external imposition on its societies. Hence, post-communist societies are expected to catch up with the successful travail de mémoire or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which are associated with Western European societies. The ‘West’ is pictured as a spring of impartial rules for facing the past, rules that might in principle flow into the Eastern periphery to resuscitate withered memories. This even seems a precondition for the kind of dialogue suitable for bridging the often-decried East-West divide. From a Polish perspective however, the question of an East-West divide is not one of rules for remembering, but about determining a factual historical truth. “For Western elites it is difficult to accept that history for Eastern Europeans does not end with Hitler and the extermination of the Jews.”[4] It is the recognition of these truths and the national histories of suffering that is seen as the precondition of dialogue. From the perspective of this mental map, historical analogies can also serve to strengthen Poland’s position in the EU, for instance, when Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk likened Germany’s North Stream 2 pipeline to the Hitler-Stalin-Pact that had divided Poland and all of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. As the pipeline was “precisely such an agreement over the heads of others,”[5] it appeared impossible in the context of European integration in the 21st century. Periphery or boundary? Another entrenched way of mapping Europe proceeds not from its internal divisions, but from its external demarcation: Where does Europe end, or, how far does Europe reach? Again, in public discourse, asking this question serves to spatialise the strife over Europe’s core values. Over the 2000s and 2010s, the position of Turkey on Europe’s mental map has been the occasion to answer this question. And as for the East-West divide, what we observe is in fact a competition between two mental maps. From an affirmative perspective, Europe represents a clearly demarcated space, based either on conservative values such as its “Christian roots” or radical Enlightenment principles which are framed as universal and secular values. A test case for the latter was the recognition of the mass killing of 1,5 million Armenians as genocide—Europe had to end where this recognition was refused. French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy, at that point in favour of Turkish EU-membership, formulated the point very clearly: “amongst the criteria fixed by Brussels for the Turkish entry into the European Union, the most important condition is lacking: the recognition of the Armenian genocide. . . . During the genocide, Turkey attempted to amputate itself of its European part. This was a genocide, and a suicide.”[6] From the viewpoint of a competing mental map, Europe appeared rather as an open space, reflexive of its own history and its cultural, historical, and religious diversity. The political motives supporting the image of such an open Europe were highly heterogeneous. From a British viewpoint, Turkey’s EU membership ambitions represented a welcome occasion for renegotiating power relations within the EU and allowed the UK to articulate more utilitarian attitudes towards European integration. For Polish conservatives, Turkey presented an alternative to a model of integration marked by secularisation and unquestioned Westernisation. Instead of further secularising Turkey, they favoured a religious turn in European integration. Accordingly, the “conservative Muslim” went to the mosque on Fridays and “the conservative Pole” to church on Sundays.[7] Jeux d’échelles A last way of mapping Europe becomes evident in the question of how Europe links to the global context. This question is of particular importance in British discourse, where memories of the Empire project a national mnemonic order onto Europe. It is noteworthy indeed that other post-imperial countries such as France, Germany, Spain or Italy do not develop on this global component through a discussion of their past. Theresa May’s call for a “truly global Britain” which had the ambition “to reach beyond the borders of Europe” testifies to how, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, British spatial imaginaries were pitted against Europe, often referencing the UK’s more flexible economy as much as the historical grandeur of a Britain before European integration. Other countries explicitly reject such framings, but do not include perspectives from outside an alleged Europe either. The discourse on ‘European memory’ mostly relied on the ‘world’ to talk exclusively about Europe. Diverging ideas of Europe beyond conflict and consensus Mental maps of European memory stake claims of what constitutes Europe, who belongs to it and where the continent ends. In the mental maps sketched out here consensus is restricted to Sunday-best speeches and the Italian canone occidentale that exemplifies a form of model Europeanism. In contrast, the other spatial imaginations rely on the conflictive character of ‘European memory’ and demarcate the continent from an internal, external or global other. These findings provide a deeper understanding of European memory underpinning ideas of European integration and may also serve for further analysis of conflicts over the idea of Europe itself. In our future research, we will inquire into the diachronic shifts of these mental maps: they reveal the entangled relation between European integration and disintegration as scenarios for a future Europe. [1] Norbert Götz and Janne Holmén, ‘Introduction to the theme issue: “Mental maps: geographical and historical perspectives”’, Journal of Cultural Geography 35(2) (2018), 157. [2] Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, Daniela Mehler, Friedemann Pestel, and Rieke Trimçev, Europäische Erinnerung als verflochtene Erinnerung – Vielstimmige und vielschichtige Vergangenheitsdeutungen jenseits der Nation (Formen der Erinnerung 55) (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht unipress), 2014. [3] ‘Sfide dopo il no di Londra’, Corriere della Sera, 18.05.2015. [4] ‘Stalinizm jak nazizm’, Rzeczpospolita, 23.02.2008. [5] https://emerging-europe.com/news/polish-minister-compares-nord-stream-2-with-molotov-ribbentrop-pact/ [6] ‘Ma non si può parlare di adesione se non si scioglie il nodo del passato’, Corriere della Sera, 23.1.2007. [7] ‘Masowa imigracja to masowe problemy’, Rzeczpospolita, 25.07.2015. |

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed