by Luke Martell

Following the explosion of the internet since the 1990s, and of smartphones and the growth of big tech corporations more recently, the politics of the digital world has drawn much attention. The digital commons, open access and p2p sharing as alternatives to enclosures and copyrighting digitally are important and have been well covered, as providing free and open rather than privatised and restricted online resources.[1] Free and open-source software (FOSS) has been important in projects in the Global South.[2] Also discussed has been the use of social media in uprisings and protest, like the Arab Spring and the #MeToo movement. There is consideration of the anxiety of some when they are not connected by computer or phone, which raises questions of the right or perceived obligation to be connected and, on the other hand, the benefits of digital detox. There are many other important analyses in the digital politics literature about matters such as expression, access, equality, the digital divide, power, openness, and innovation.[3] I focus here on alternatives in the light of recent surveillance and privacy concerns that have come to the fore since the Snowden affair in 2013, the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018, and the Pegasus spyware revelations in 2021. US intelligence whistleblower Edward Snowden exposed widespread phone and internet surveillance by US and other security agencies. The firm Cambridge Analytica collected extensive personal data of tens of millions of Facebook users, without their consent, for political advertising, although they may have exaggerated what they did or were able to. The NSO technology company were found to have installed Pegasus surveillance spyware on the phones of politicians, journalists, and activists for number of states. There have been numerous hacks and mega-leaks of individual and company data.

Big tech corporations like GAFAM—Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Facebook (Meta), Apple, and Microsoft—have come to dominate and create oligopolies in the digital and tech worlds (another acronym FAANG includes Netflix but not Microsoft). More internationally communications social media like WeChat, Line, Discord, and QQ have become pervasive. GAFAM have an extensive hold over sectors such that we are constrained inside their walled gardens to get the online services we want or have come to rely on. Google is a prominent example; it is difficult, for instance, to operate an Android phone without using them, the company’s early motto ‘Don’t be Evil’ not to be seen any more these days. These companies’ oligopolies over tech and the digital are of concern because they limit our ability to choose and be free, and so is their invasion of personal spaces with surveillance and the capturing of personal information. Many of the corporations gather information about our digital activities, searches, our IP addresses, interests, contacts, and messaging, using algorithmic means. The information is captured and aggregated, and value is created from surveillance, the extractive process of data mining, the selling of personal information, and the creation of models of user behaviour for directing advertising and nudging. In this system, it is said, the user or consumer is the product, the audience the commodity. Data is seen as the new oil, where the oil of the digital economy is us. The produce is the models created to manipulate consumers. We are often so reliant on such providers it is difficult to avoid this information being collected, something done in a way which is complex and opaque, so hard for us to see and respond to. It is often in principle carried out with our consent but withdrawing consent is so complicated and the practices so obscure and normalised for many that in effect we are giving it without especially wanting to. The information gathered is also available on request, in many cases to varying degrees in different contexts, to governments and police. Sometimes states use the corporate databases of companies like Palantir, avoiding legal restrictions on government use of citizen data, especially in the USA, to monitor some of the most mainstream, benign, and harmless groups and individuals. There are reports of a ‘chilling effect’ where people are hesitant about saying things or using online resources like searches in a way they feel could attract unjustified government attention. Questioning approaches to this situation have focused on critique, and action has homed in on boycotts, e.g. of platforms like Facebook, and more general disconnection and unplugging. There is a ‘degoogling’ movement of people who wish to go online and use the Internet, computers and smartphones in ways that avoid organisations like Google. For many, degoogling (or de-GAFAMing) is a complex process, technically and in the amount of work and time involved. Privacy concerns are also followed through by the avoidance of non-essential cookies and using tracking blockers, encryption, and other privacy tools like browser extensions and Virtual Private Networks. Apple builds privacy and blocking means into its products to the consternation of Facebook who have an advertising-led approach. Mozilla has taken a lead in making privacy tools available for its Firefox browser and beyond. At state level, responses have been oriented to attempting to limit monopolisation and ensure competition, although these have not stopped oligopolies in digital information and tech. There is variation internationally in anti-monopoly attempts by states or the supranational EU. States have varying privacy laws limiting access to personal information digitally, with governments like the Swiss being more rigorous and outside the ‘eyes’ states that share intelligence, while states like the Dutch have moved from stronger to weaker privacy laws. The ‘five eyes’ states Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and USA have a multilateral agreement to spy on citizens and share the collected intelligence with one another. So, those beyond the ‘eyes’ states are not obligated to sharing citizens’ private data at the request of other powers. EU GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) legislation is important in this context. The radical politics of alternatives in the Arab Spring, and the Occupy and anti-austerity movements have often relied on social media such as Twitter to organise and act. Many in such movements believe in independence and autonomy including in conventional media but do not go much beyond critique to digital alternatives, which can remain the preserve still of the tech-minded and committed. The latter sometimes have a political critique and approach but often just privacy concerns within an effectively liberal or libertarian approach. One approach, ‘cyber-libertarianism’, is against obstacles to a free World Wide Web, such as government regulation and censorship, although Silicon Valley that it is identified with is also quite liberal, in the USA sense, and concerned with labour rights. An emphasis of activists on openness and transparency can be given as reason for not using means, such as encryption and other methods mentioned above, for greater privacy and anonymity in information and communication. There is less expansion beyond critique, boycotting and evasion of privacy incursions to alternatives. However, alternatives there are, and these involve decentralised federated digital spaces where individuals and groups can access internet resources for communication and media from means that are alternative to GAFAM and plural, so we are not reliant on single or few major corporations. Some of these alternatives promise greater emphasis on privacy, not collecting or supplying our information to commerce or the state and, to different degrees, encryption of communication or information in transit or ‘at rest’, stored on servers. In some cases, encryption in alternatives is not much more extensive than through more mainstream providers, but we are assured on trust that that our data will not be read, shared, or sold. Many alternatives build free and open-source software provided not for profit or gain and sometimes, but not always, by volunteers. Code is open source rather than proprietary so we can see and access it and assess how the alternatives operate and can use and adapt the code. Some provide alternatives to social media like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit (such as Mastodon, Diaspora, and Lemmur) and to mainstream cloud storage, messaging (e.g., Signal) and email, although some of the alternative fora have low levels of users and activity and many critical and alternatives-oriented activists are still pushed to using big corporate suppliers for quantity of content and users. Groups like Disroot, a collective of volunteers, provide alternative email which limits the collection, storage and sharing of personal details. Disroot offers links to many platforms alternative to the big corporations for email, messaging, chatting, social media and cloud hosting. Groups like Riseup, a leftist and activist platform, provide invite-only email, data storage on their own servers, and other means for digital activity beyond big corporations and prying eyes to whom they intend to not divulge information, although sometimes limited by levels of encryption and the laws of the states where they are sited. Email providers like Protonmail and Tutanota promise not to collect information about users and to encrypt our communication more rigorously so we can avoid both GAFAM and surveillance. Some of these are still capitalist corporations, but with a privacy emphasis, although semi-alternative companies like Runbox and Infomaniak are worker-owned. Autistici, like Disroot, is volunteer-run on non-capitalist lines, monetary aspects limited to voluntary donation. Both have an anarchist leaning, Autistici more explicitly committed to an autonomous anti-capitalist position. Some alternative providers (like Runbox, Tutanota, and Posteo) have green commitments, using renewable energy to reduce carbon emissions. Others go beyond a corporate form and have more of a social movement identity. There are campaigning organisations that focus on digital rights and freedom, and crypto-parties that help people adopt privacy and anonymity means in their digital activity. Some alternative privacy-oriented platforms gained more attention and users after the Snowden affair, but many otherwise alternatives-oriented people continue to use providers like Google because they do not know about the alternatives or switching to them is, sometimes justifiably, seen as a big job. Others are resigned to the belief that email and such online activity can never be private or take alternative tracking blocking measures while continuing to use mainstream resources in, for example, email. For some users there is much to be gained by what data harvesting allows, for instance personalisation of content and making connections with others across platforms like Facebook and Instagram, or they feel that most of the data collected is trivial for them and so accepted. In such cases the dangers and morality of data harvesting and selling are not worrying enough to resist or avoid it. There may also be less individualistic benefits for social research and improvement of tech and the digital that, for some, make some of the data gathering outweigh privacy incursions. Many of the alternatives are at the level of software and online providers, but this leaves the sphere of hardware and connectedness, where it is possible for states to stop resistance and rebellion by turning the internet off or censoring it, as in China, Egypt, and Iran amongst many other cases. There are alternatives for hardware, for instance in the open-source hardware movement, and for connectedness through devices linked independently in infrastructure or mesh networks. Interest in these lags behind that in software alternatives and their effectiveness depends on how many join such networks.[4] So, the alternatives are around a politics of privacy, independence and autonomy alongside anti-monopoly and sometimes non-capitalist and green elements. It has been argued that the digital world as it is requires the insertion of concepts of anonymity[5] alongside concerns such as equality, liberty, democracy, and community in the lexicon of political ideas and concerns, and anonymity rather than oft advocated openness or transparency, a key actor in digital alternatives having been the network ‘Anonymous’. While anonymity is desirable, just as it is when wished for in the offline world, it faces limits in the face of what has been called ‘surveillance capitalism’.[6] Firstly, this is because, as offline, anonymity and privacy are difficult to achieve if faced with a determined high-level authority like a government, as the Snowden and Pegasus affairs showed. Secondly, seeking anonymity is a reactive and evasive approach. For a better world what is needed is resistance and an alternative. Resistance involves tackling the power of big tech and the capturing of data they are allowed. Via social movements and states this needs to be challenged and turned back. And in the context of alternatives, alternative tech and an alternative digital world needs to be expanded. So, implied is a regulated and hauled back big tech and its replacement by a more plural tech and digital world, decentralised and federated. One advocate of the latter is Tim Berners-Lee, credited as the founder of the World Wide Web. Anonymity may be desirable individually and for groups, but collectively what is required is overturning of big intrusive tech by state power, through regulation, anti-monopoly activity and public ownership. The UK Labour Party went into the 2019 General Election with a policy of nationalising broadband, mainly for inclusivity and rights to connectedness reasons, but opening up the possibility of other ends public ownership can secure. But state power can be a problem as well as a tool so the alternative of decentralised, collectivist, democratic tech is needed too in a pluralist digital world. So, to recap and clarify key points. Oligopoly and the harvesting and selling of our digital lives has become a norm and a new economic sector of capitalism. State responses, to very different degrees, have been to resist monopolisation and ensure modest privacy protections or awareness. Individual responses and those of some organisations have been to use software that blocks tracking and aims to maintain privacy and anonymity. But positive as these methods are, they are in part defensive, limited in what they can achieve against high-level attempts at intrusion, and some of these individualise action. Alongside such state and individual processes, we need a more pro-active and collective approach. This includes stronger regulation and breaking up and taking tech into collective ownership. In the sphere of alternatives, it means expanding and strengthening a parallel sphere, decentralised and federated. And alternatives require putting control in the hands of those affected, so collective democracy with inclusive participation. Then oligopolies are challenged and there is a link between those affected and those in control. But alternatives must be made accessible and more easily understandable to the non-techy and beyond the expert, and do not just have to be an alternative but can be a prefigurative basis for spreading to the way the digital and tech world is more widely. This involves supplementing liberal individual privacy and rights approaches, often defensive within the status quo, with collective democracy and control approaches, more proactive and constructive of alternatives[7]. If there is an erosion of capitalism out of such an approach so there will be also to profit incentives in surveillance capitalism. With an extension of collective control not-for-profit, then motivations for surveillance and data capture are reduced. But this must be done through inclusive democratic control (by workers, users and the community) as much as possible rather than the traditional state, as the latter has its own reasons for surveillance. It should be supplemented by a pluralist, decentralised, federated, digital world to counter oligopoly and power. Democratisation that is inclusive globally is also suited to dealing with differences and divides digitally, e.g. by class or across the Global North and Global South. Taken together this approach implies pluralist democratic socialism as well as liberalism, rather than capitalism or the authoritarian state. I am grateful to David Berry for his very helpful advice on this article. [1] Berry, D. (2008) Copy, Rip, Burn: The Politics of Copyleft and Open Source, London: Pluto Press. [2] Pearce, J (2018) Free and Open Source Appropriate Technology, in Parker, M. et al (eds) The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, London: Routledge. [3] For a good overview and analysis of the area see Issin, E. and Ruppert, E. (2020) Being Digital Citizens, London: Rowman and Littlefield. See also Bigo, D., Issin, E., and Ruppert, E. (eds) (2019) Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London: Routledge, and Muldoon, J. (2022) Platform Socialism: How to Reclaim our Digital Future from Big Tech, London: Pluto Press. [4] See Lopez, A. and Bush, M.E.L., (2020) Technology for Transformation is the Path Forward, Global Tapestry of Alternatives Newsletter, July. https://globaltapestryofalternatives.org/newsletters:01:index [5] Rossiter, N. and Zehle, S., (2018) Towards a Politics of Anonymity: Algorithmic Actors in the Constitution of Collective Agency and the Implications for Global Economic Justice Movements, in Parker et al (eds) The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, London: Routledge. [6] Zuboff, S., (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, London: Profile Books. [7] See Liu, W. (2020) Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology from Capitalism, London: Repeater Books. by Marius S. Ostrowski

In May 2021, the British broadcaster ITV launched a new advertising campaign to showcase the range of content available on its streaming platform ITV Hub. In a series of shorts, stars from the worlds of drama and reality TV go head-to-head in a number of outlandish confrontations, with one or the other (or neither) ultimately coming out on top. One short sees Jason Watkins (Des, McDonald & Dodds) try to slip Kem Cetinay (Love Island) a glass of poison, only for Kem to outwit him by switching glasses when Jason’s back is turned. Another has Katherine Kelly (Innocent, Liar) making herself a gin and tonic, opening a cupboard in her kitchen to shush a bound and gagged Pete Wicks (The Only Way is Essex). A third features Ferne McCann (I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, The Only Way is Essex) rudely interrupting Richie Campbell (Grace, Liar) in the middle of a crucial phonecall by raining bullets down on him from a helicopter gunship. And the last, most recent advert shows Olivia Attwood (Love Island) and Bradley Dack (Blackburn Rovers) distracted mid-walk by an adorable dog, only to have a hefty skip dropped on them by Anna Friel (Butterfly, Marcella).

The message of all these unlikely pairings is clear. In this age of binge-watching, lockdowns, and working from home, ITV is stepping up to the plate to give us, the viewers, the very best in premium, popular, top-rated televisual content to satisfy every conceivable taste. Against the decades-long rise of subscription video-on-demand streaming, one of the old guard of terrestrial television is going on the offensive. Netflix? Prime? Disney+? Doesn’t have the range. Get you a platform that can do both. (BAFTA-winning drama and Ofcom-baiting reality, that is.) More a half-baked fighting retreat than an all-out assault? Think again; ITV is “stopping at nothing in the fight for your attention”. Can ITV really keep pace with the bottomless pockets of the new media behemoths? Of course it can. Even without a wealth of resources you can still have a wealth of choice. The eye-catching tagline for all this: “More drama and reality than ever before.” In this titanic struggle between drama and reality, the central irony—or, perhaps, its guilty secret—is how often the two sides of this dichotomy fundamentally converge. The drama in question only very rarely crosses the threshold into true fantasy, whether imagined more as lurid science-fiction or mind-bending Lovecraftian horror; meanwhile, reality is several stages removed from anything as deadening or banal as actual raw footage from live CCTV. Instead, the dramas that ITV touts as its most successful examples of the genre pride themselves on their “grittiness”, “believability”, and even “realism”. At the same time, the “biggest” reality shows are transparently “scripted” and reliant on “set-ups” and other manipulations by interventionist producers, and the highest accolade their participants can bestow on one another is how “unreal” they look. Both converge from different sides on an equilibrium point of simulated, real-world-dramatising “hyperreality”; and as we watch, we are unconsciously invited to ask where drama ends and where reality begins. In our consumption of drama and reality, we are likewise invited to “pick our own” hyperreality from the plethora of options on offer. The sheer quantity of content available across all these platforms is little short of overwhelming, and staying up-to-date with all of it is a more-than-full-time occupation. Small wonder, then, that we commonly experience this “wealth of choice” as decision “fatigue” or “paralysis”, and spend almost as much if not often more time scrolling through the seemingly infinite menus on different streaming services than we do actually watching what they show us. But the choices we make are more significant than they might at first appear. The hyperrealities we choose determine how we frame and understand both the world “out there” within and beyond our everyday experiences and the stories we invent to describe its horizons of alternative possibility. They decide what we think is (or is not) actually the case, what should (or should not) be the case, what does (and does not) matter. Through our choice of hyperreality, we determine how we wish both reality and drama to be (and not to be). Given the quantity of content available, the choice we make is also close to zero-sum. As the “fight for our attention” trumpeted by ITV implies, our attention (our viewing time and energy, our emotional and cognitive engagement) is a scarce resource. Even for the most dedicated bingers, picking one or even a few of these hyperrealities to immerse ourselves in sooner or later comes at the cost of being able to choose (at least most of) the others. We have to choose whether our preferred hyperreality is dominated by “glamorous singles” acting out all the toxic and benign microdynamics of heterosexual attraction, or the murky world of “bent coppers” and the rugged band of flawed-but-honourable detectives out to expose them; whether it smothers us in parasols and petticoats, and all the mannered paraphernalia of period nostalgia, or draws us into the hidden intricacies of a desperately-endangered natural world. In short, we have to choose what it is about the world that we want to see. * * * We face the same overload of reality and drama, and the same forced choice, when we engage with the more direct mediatised processes that provide us with information about the world around us. Through physical, online, and social media, we are met with a ceaseless barrage of new, drip-fed, self-contained events and phenomena, delivered to us as bitesize nuggets of “content”. Before, we had the screaming capitalised headlines and one-sentence paragraphs of the tabloid press. Now, we also have Tweets (and briefly Fleets), Instagram stories and reels, and TikTok videos generated by “new media” organisations, “influencers” and “blue ticks”, and a vast swarm of anonymous or pseudonymous “content providers”. All in all, the number of sources—and the quantity of output from each of these sources—has risen well beyond our capacity to retain an even remotely synoptic view of “everything that is going on”. Of course, it is by now a well-rehearsed trope that these bits of “news” and “novelty” content leave no room for nuance, granularity, and subtlety in capturing the complexities of these events and phenomena. But what is less-noticed are the challenges they create for our capacity to make meaningful sense of them at all from our own (individual or shared) ideological stances. Normally, we gather up all the relevant informational cues we can, then—as John Zaller puts it—“marry” them to our pre-existing ideological values and attitudes, and form what Walter Lippmann calls a “picture inside our heads” about the world, which acts as the basis for all our subsequent thought and action.[1] But the more bits of information we are forced to make sense of, and the faster we have to make sense of them “in live time” as we receive them—before we can be sure about what information is available instead or overall—the more our task becomes one of information-management. We are preoccupied with finding ways to get a handle on information and compressing it so that our resulting mental pictures of the world are still tolerably coherent—and so that our chosen hyperreality still “works” without too many glitches in the Matrix. These processes of information-management are far from ideologically neutral. As consumers of information, our attention is not just passive, there to be “fought over” and “grabbed”; rather, we actively direct it on the basis of our own internalised norms and assumptions. We are hardly indiscriminately all-seeing eyes; we are omnivorous, certainly, but like the Eye of Sauron our voracious absorption of information depends heavily on where exactly our gaze is turned. In this context, what is it that ideology does to enable us to deal with information overload? What tools does it offer us to form a viable representation of the world, to help us choose our hyperreality? * * * One such tool is the iterative process of curating the “recommended-for-you” information that appears as the topmost entries in our search results, home pages, and timelines. The cues we receive are blisteringly “hot”, to use Marshall McLuhan’s term; they are rhetorically and aesthetically marked or tagged—“high-spotted” in Edward Bernays’ phrase—to elicit certain emotional and cognitive reactions, and steer us towards particular “pro–con” attitudes and value-judgments.[2] They “fight for our attention”, clamouring loudly to be the first to be fed through our ideological lenses; and they soon exhaust our capacity (our time, energy, engagement) to scroll ever on and absorb new information. To stave off paralysis, we pick—we have to pick—which bits of information we will inflate, and which we want to downplay. In so doing, we implicitly inflate and downplay the ideological frames and understandings attached to them in “high-spotted” form. Then, of course, the media platform or search engine algorithm remembers and learns our choice, and over time gradually takes the need to make it off our hands, quietly presenting us with only the information (and ideological representations) we “would” (or “should”) have picked out. “Siri, show me what I want to see.” “Alexa, play what I want to hear.” No surprise, then, that the difference in user experience between searching something in our usual browser or a different one can feel like paring away layers of saturation and selective distortion. The fragmentary nature of how we receive information also changes how we express our reaction to it. The ideologically-exaggerated construction of informational cues is designed to provoke instant, “tit-for-tat” responses. At the same time, the promise of “going viral” creates an algorithmic incentive to move first and “move mad” by immediately hitting back in the same medium with a response that is at least as ideologically exaggerated and provocative as the original cue if not more. Gone are the usual cognitive buffers designed to optimise “low-information” reasoning and decision-making. Instead, we are pushed towards the shortest of heuristic shortcuts, the paths of least intellectual resistance, into an upward—and outward (polarising)—spiral of “snap” judgments. The “hot take” becomes the predominant way for us to incorporate the latest information into our ideological pictures of the world; any longer and more detailed engagement with this information is created by literally attaching “takes” to each other in sequence (most obviously via Twitter “threads”). As this practice of instantaneous reaction becomes increasingly prominent and entrenched, our pre-existing mental pictures are steadily overwritten by a worldview wholly constituted as a mosaic of takes: disjointed, simplistic, foundationless, and subjective. As our ideological outlook becomes ever more piecemeal, we turn with growing urgency to the tools and structures of narrative to bring it some semblance of overarching unity. Every day, we consult our curated timelines and the cues it presents to us to discover “the discourse” du jour—the primary topic of interest on which our and others’ collective attention is to focus, and on which we are to have a take. Everything about “the discourse” is thoroughly narrativised: it has protagonists (“the OG Islanders”) and a supporting cast (“new arrivals”, “the Casa Amor girls”), who are slotted neatly into the roles of heroes (Abi, Kaz, Liberty) or villains (Faye, Jake, Lillie); it undergoes plot development (the Islanders’ “journeys”), with story and character arcs (Toby’s exponential emotional growth), twists (the departure of “Jiberty”) and resolutions (the pre-Final affirmations of “Chloby”, “Feddy”, “Kyler”, and “Milliam”). We overcome both the sheer randomness of events as they appear to us, and the pro–con simplicity of our judgments about them, by reimagining each one as a scene in a contemporary (im)morality play—a play, moreover, in which we are partisan participants as much as observers (e.g., by voting contestants off or adding to their online representations). How far this process relies on hermetically self-contained, self-referential certainty becomes clear from the discomfort we feel when objects of “the discourse” break out of this narrative mould. The howls of outrage that the mysterious figure of “H” in Line of Duty turned out not to be a “Big Bad” in the style of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but instead a floating signifier for institutional corruption, shows how conditioned we have become to crave not only decontestation but substantial closure. The final element in our ideological arsenal that helps us cope with the white heat of the cues we receive is our ability to look past them and focus on the contextual and metatextual penumbra that surrounds them. To make sure we are reading our fragmentary information about the world “correctly”, we search for additional clues that take (some or all of) the onus of curating it, coming up with a take about it, and shaping it into a narrative off our hands. This explains, for instance, the phenomenon where audiences experience Love Island episodes on two levels simultaneously, first as viewers and second as readers of the metacommentary in their respective messenger group chats, and on “Love Island Twitter”, “Love Island TikTok”, and “Love Island Instagram”. In extreme cases, we outsource our ideological labour almost entirely to these clues, at the expense of engaging with the information itself, as it were, on its own terms. “Decoding” the messages the information contains then becomes less about knowing the right “code” and more about being sufficiently familiar with who is responsible for “encoding” it, as well as when, where, and how they are doing so. Rosie Holt has aptly parodied this tendency, with her character vacillating between describing a tweet as nice or nasty (“nicety”) and serious (“delete this”) or a joke (“lol”), incapable of making up her mind until she has read what other people have said about it. * * * Together, these elements create a kind of modus vivendi strategy, which we can use to cobble together something approaching a consistent ideological representation of what is going on in the world. But its highly in-the-moment, “choose-your-own-adventure” approach threatens to give us a very emaciated, flattened understanding of what ideology is and does for us. Specifically, it is a dangerously reductionist conception of what ideology has to offer for our inevitable project of choosing a hyperreal mental picture that navigates usefully between (overwhelming, nonsensical) reality and (fanciful, abstruse) drama. If a modus vivendi is all that ideology becomes, we end up condemned to seeing the world solely in terms of competing “mid-range” narratives, without any overarching “metanarratives” to weave them together. These mid-range narratives telescope down the full potential extent of comparisons across space and trajectories over time into the limits of what we can comprehend within the horizons of our immediate neighbourhood and our recent memory. What we see of the world becomes limited to a litany of Game of Thrones-style fragmentary perspectives, more-or-less “(un)reliable” narrations from myriad different people’s angles—which may coincide or contradict each other, but which come no closer to offering a complete or comprehensive account of “what is going on”. The tragic irony is that the apotheosis of this information-management style of ideological modus vivendi is taking place against a backdrop of a reality that is itself taking on ever more dramatic dimensions on an ever-grander scale. Literal catastrophes such as climate change, pandemics, or countries’ political and humanitarian collapse raise the spectral prospect of wholesale societal disintegration, and show glimpses of a world that is simultaneously more fantastical and more raw than what we encounter as reality day-to-day. Individual-level, “bit-by-bit” interpretation is wholly unequipped to handle that degree of overwhelmingness in the reality around us. Curating the information we receive, giving our takes on it, crafting it into moralistic narratives, and interpreting its supporting cues is a viable way to offer an escape (or escapism) from the stochastic confusion of the “petty” reality of our everyday experience—to “leaven the mundanity of your day”, as Bill Bailey puts it in Tinselworm. But it falls woefully short when what we have to face is a reality that operates at a level well beyond our immediate personal experience, which is “sublimely” irreducible to anything as parochial as individual perspective. How unprepared the ideological modus vivendi calibrated to the mediatisation of information today leaves us is shown starkly by the comment of an anonymous Twitter user, who wondered whether we will experience climate change “as a series of short, apocalyptic videos until eventually it’s your phone that’s recording”. If it proves unable to handle such “grand” reality, ideology threatens to become what the Marxist tradition has accused it of being all along: namely, an analgesic to numb us out of the need to take reality on its own ineluctable terms. That, ultimately, is what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were trying to provide through their accounts of historical materialism and scientific socialism: an articulation of a narrative capable of addressing, and as far as possible capturing, the sheer scale and complexity of reality beyond the everyday. We do not have to take all our cues from Marxism—even if, as often as not, “every little helps”. But we do have to inject a healthy dose of grand narrative and metanarrative back into the ideologies we use to represent the world around us, even if only to know where we stand among the tides of social change from which the “newsworthy” events and phenomena we encounter ultimately stem. The trends driving the reality we want to narrate are simultaneously global and local, homogenised and atomised, universal and individuated. We cannot focus on one at the expense of the other. By itself, neither the “Olympian” view of sweeping undifferentiated monological macronarratives (Hegelian Spirit, Whig progress, or Spenglerian decline) nor the “ant’s-eye” view of disconnected micronarratives (of the kind that contemporary mediatisation is encouraging us to focus on) will do. The only ideologies worth their salt will be those that bridge the two. How, then, should ideology respond to the late-modern pressures that are generating “more drama and reality than ever before”? Certainly, it needs to recognise the extent to which these are opposite pulls it has to satisfy simultaneously: no ideological narrative can afford to lose the contact with “gritty” reality that makes it empirically plausible, nor the “production values” of drama that make it affectively compelling. At the same time, it has to acknowledge that the hyperreality it creates and chooses for us is never fully immune to risk. Dramatic “scripting” imposes on reality a meaningfulness and direction that the sheer chaotic randomness of “pure” reality may always eventually belie. Meanwhile, the slavish drive to “accurately” simulate reality may ultimately sap our orientation and motivation in engaging with the world around us of any dramatic momentum. The only way to minimise these risks is to “think big”, and restore to ideology the ambition of “grand” and “meta” perspective, to reflect the maximum scale at which we can interpret both what (plausibly) is and what (potentially) is to be done. [1] Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (Blacksburg, VA: Wilder Publications, Inc., 2010 [1922]), 21–2; John R. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 51. [2] Edward Bernays, Propaganda (Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2005 [1928]), 38; Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (New York, NY: McGraw–Hill, 1964), 22ff. by Rieke Trimçev, Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, and Friedemann Pestel

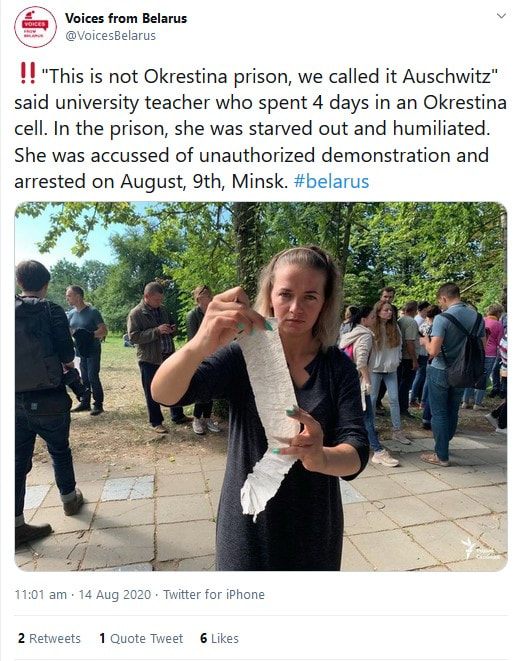

During the upheaval against Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus after the contested presidential election in August 2020, the idea of ‘Europe’ has often been invoked. These invocations might be surprising, given that Belarusians themselves have shunned explicit references to the EU and that EU flags were absent on the country’s streets. Instead, a rhetorical call to Europe has served to amplify demands for the support of Belarusian society and direct Europe’s attention to a country long-neglected by the international community. Lithuania’s former foreign secretary stated on Twitter: “The 21st century. The heart of Europe – Belarus. A criminal gang a.k.a. ‘Police Department of Fighting Organized Crime’ terrorizing Belarusians who have been peacefully demanding freedom and democracy for already 80 consecutive days. Shame!” Designating a particular region as “the heart of Europe” is a popular rhetorical device, acting as a way to call for attention. During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Margaret Thatcher used the metaphor to denounce the E.C.’s failure to prevent the mass killings in Bosnia: “this is happening in the heart of Europe […] It should be within Europe’s sphere of conscience.” The force of this phrasing defies geographical reality and lies in elevating specific values and principles as central to the idea of Europe. Europe’s political activity should live up to these values, simply to protect a vital part of its body. Through this formula, places like Belarus or Bosnia become part of a shared mental map, understood as a “spatialisation of meaning [that] dwells latently in the minds of individuals or groups of people.”[1] Another look at the rhetoric of the Belarusian protests indicates that shared representations of the past and the language of memory are particularly powerful tools in spatialising meaning and increasing the visibility of regional events for a transnational audience. All these tweets and pictures compare the Okrestina Detention Centre in Minsk, where many of the protesters were interned, to the Nazi extermination camp Auschwitz. Leaving aside the question of whether such comparisons are appropriate, their implication for protesters is clear: “The heart of Europe” is where Europe’s founding norm of “Never again!” is at risk.

The spatialised communication of normative arguments are at the core of our ongoing research project on the contested languages of European memory—“Europe’s Europes” if you will. It is informed by a larger qualitative study, in which we study public ideas of Europe through the prism of representations of the past and the language of memory. Examining press discourse in France, Germany, Poland, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2018, we have reconstructed several entrenched mental maps of Europe, which differ according to regional perspectives, ideological stances or historical trajectories. Some of these imaginaries—“Europe’s Europes”—complement each other, while others stand in open or implicit contradiction and provoke conflicts over the mental geography of Europe. To say that they are “entrenched” mental maps means that they are deeply rooted in everyday thought-behaviour and help to make sense of today’s political challenges. It is here that the language of memory, whose importance in forming shared senses of identity has long been noted, shows its ideological pertinence even beyond debates over memory politics strictly speaking.[2] Understanding these mental maps allows us to better seize discursive deadlocks, but also to identify missed encounters in debating in, over and with Europe. Islands of consensus The metaphor of the “heart of Europe” pictures Europe as a body whose different parts naturally work together to assure the functioning of a holistic “community of values”. While this metaphor might sound unsurprising, it turns out to be a concept that has a limited discursive reach, and is of limited agency when it comes to everyday political debates beyond grandiose speeches. In our study, we found that Europe is predominantly understood as a contested idea. Most of the deep-rooted mental maps spatialise this contestation through imaginary borders, both internal and external. Against the predominance of these fractured mental maps, ideas of Europe as a consensual community of values appear as “islands of consensus” of limited discursive reach. Between 2004 and 2018, one such “island of consensus” structured significant parts of the Italian press discourse, where Europe was pictured as a continent united through a canone occidentale, embracing Antiquity, Judaeo-Christian roots, Enlightenment, Liberalism, and other historical cornerstones with a positive connotation. This idea of a European canon also occurs in other national discourses but is more partisan. Especially in times of crisis, speaking from within a community of values has allowed for a clear yardstick of judgment. For example, the failure to set up a joint accommodation system for migrants in 2015, from the viewpoint of this mental map, appeared to betray European memory—a memory which had claimed a humanitarian impetus when boatpeople had fled from communism in the 1970s and 1980s: “On the issue of immigration, the Europe of the single currency and strengthened political governance seems less cohesive and less aware than Europe at the time of the Berlin Wall and the Cold War. The memory of the new Europeans and the new ruling classes seems indifferent to recent history.”[3] Yet, the moral self-confidence of dwellers of an island of consensus comes at some cost. From the perspective of an island of consensus, conflicts appear as a misunderstanding that could be solved by proper integration, inclusive of a European memory. However, this perspective remained largely confined to Italy and found little echo in other discursive spheres. Frictions between ‘East’ and ‘West’ A particularly prominent way of spatialising the meaning of Europe revolves around an East-West divide. While it is prominent both in ‘old Europe’ and those post-communist countries that joined the EU in 2004, it must be understood as the junction of two different, and in fact competing mental mappings. For France and Germany, ‘Eastern Europe’ largely represents a mnemonic terrain on which, after 1945, the communist regimes froze the memories of World War 2 and the Holocaust, and which still today rejects communist rule as an external imposition on its societies. Hence, post-communist societies are expected to catch up with the successful travail de mémoire or Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which are associated with Western European societies. The ‘West’ is pictured as a spring of impartial rules for facing the past, rules that might in principle flow into the Eastern periphery to resuscitate withered memories. This even seems a precondition for the kind of dialogue suitable for bridging the often-decried East-West divide. From a Polish perspective however, the question of an East-West divide is not one of rules for remembering, but about determining a factual historical truth. “For Western elites it is difficult to accept that history for Eastern Europeans does not end with Hitler and the extermination of the Jews.”[4] It is the recognition of these truths and the national histories of suffering that is seen as the precondition of dialogue. From the perspective of this mental map, historical analogies can also serve to strengthen Poland’s position in the EU, for instance, when Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk likened Germany’s North Stream 2 pipeline to the Hitler-Stalin-Pact that had divided Poland and all of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. As the pipeline was “precisely such an agreement over the heads of others,”[5] it appeared impossible in the context of European integration in the 21st century. Periphery or boundary? Another entrenched way of mapping Europe proceeds not from its internal divisions, but from its external demarcation: Where does Europe end, or, how far does Europe reach? Again, in public discourse, asking this question serves to spatialise the strife over Europe’s core values. Over the 2000s and 2010s, the position of Turkey on Europe’s mental map has been the occasion to answer this question. And as for the East-West divide, what we observe is in fact a competition between two mental maps. From an affirmative perspective, Europe represents a clearly demarcated space, based either on conservative values such as its “Christian roots” or radical Enlightenment principles which are framed as universal and secular values. A test case for the latter was the recognition of the mass killing of 1,5 million Armenians as genocide—Europe had to end where this recognition was refused. French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy, at that point in favour of Turkish EU-membership, formulated the point very clearly: “amongst the criteria fixed by Brussels for the Turkish entry into the European Union, the most important condition is lacking: the recognition of the Armenian genocide. . . . During the genocide, Turkey attempted to amputate itself of its European part. This was a genocide, and a suicide.”[6] From the viewpoint of a competing mental map, Europe appeared rather as an open space, reflexive of its own history and its cultural, historical, and religious diversity. The political motives supporting the image of such an open Europe were highly heterogeneous. From a British viewpoint, Turkey’s EU membership ambitions represented a welcome occasion for renegotiating power relations within the EU and allowed the UK to articulate more utilitarian attitudes towards European integration. For Polish conservatives, Turkey presented an alternative to a model of integration marked by secularisation and unquestioned Westernisation. Instead of further secularising Turkey, they favoured a religious turn in European integration. Accordingly, the “conservative Muslim” went to the mosque on Fridays and “the conservative Pole” to church on Sundays.[7] Jeux d’échelles A last way of mapping Europe becomes evident in the question of how Europe links to the global context. This question is of particular importance in British discourse, where memories of the Empire project a national mnemonic order onto Europe. It is noteworthy indeed that other post-imperial countries such as France, Germany, Spain or Italy do not develop on this global component through a discussion of their past. Theresa May’s call for a “truly global Britain” which had the ambition “to reach beyond the borders of Europe” testifies to how, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, British spatial imaginaries were pitted against Europe, often referencing the UK’s more flexible economy as much as the historical grandeur of a Britain before European integration. Other countries explicitly reject such framings, but do not include perspectives from outside an alleged Europe either. The discourse on ‘European memory’ mostly relied on the ‘world’ to talk exclusively about Europe. Diverging ideas of Europe beyond conflict and consensus Mental maps of European memory stake claims of what constitutes Europe, who belongs to it and where the continent ends. In the mental maps sketched out here consensus is restricted to Sunday-best speeches and the Italian canone occidentale that exemplifies a form of model Europeanism. In contrast, the other spatial imaginations rely on the conflictive character of ‘European memory’ and demarcate the continent from an internal, external or global other. These findings provide a deeper understanding of European memory underpinning ideas of European integration and may also serve for further analysis of conflicts over the idea of Europe itself. In our future research, we will inquire into the diachronic shifts of these mental maps: they reveal the entangled relation between European integration and disintegration as scenarios for a future Europe. [1] Norbert Götz and Janne Holmén, ‘Introduction to the theme issue: “Mental maps: geographical and historical perspectives”’, Journal of Cultural Geography 35(2) (2018), 157. [2] Gregor Feindt, Félix Krawatzek, Daniela Mehler, Friedemann Pestel, and Rieke Trimçev, Europäische Erinnerung als verflochtene Erinnerung – Vielstimmige und vielschichtige Vergangenheitsdeutungen jenseits der Nation (Formen der Erinnerung 55) (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht unipress), 2014. [3] ‘Sfide dopo il no di Londra’, Corriere della Sera, 18.05.2015. [4] ‘Stalinizm jak nazizm’, Rzeczpospolita, 23.02.2008. [5] https://emerging-europe.com/news/polish-minister-compares-nord-stream-2-with-molotov-ribbentrop-pact/ [6] ‘Ma non si può parlare di adesione se non si scioglie il nodo del passato’, Corriere della Sera, 23.1.2007. [7] ‘Masowa imigracja to masowe problemy’, Rzeczpospolita, 25.07.2015. by Angela Xiao Wu

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy, or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced by a government, political party or other entity or individual in a capacity of contextual authority.

Before the Lunar New Year, Beijing’s winter was brutal. I bicycled daily from my college dormitory to an intensive class for the GRE test required for US graduate schools. In the camp, a talkative guy named Luo Yonghao was responsible for coaching vocabulary sessions. Buried in piles of workbooks, 200 students listened to his venting, jokes, and meandering comments about silly Chinese norms in culture and politics. It was 2004, and I was a sophomore. Much of my college days had gone into ploughing through commentaries and memoirs chaotically dumped in online forums. These materials were too “sensitive” for broadcast media. With this inoculation, I found Luo’s extracurricular offerings delightful and amusing. But I was oblivious to what came next from him. Locating the Chinese Dissent China entered the “Year of the Blog” in 2005. In 2006, as blogging underwent rapid commercialization, Luo Yonghao left his GRE coaching job and founded an independent blogging platform called Bullog. About the same time, I started my M.Phil. studies in Hong Kong. Each day sprawling networks of online writers engaged in endless fierce disputes. Rivalry aside, their implicit addressees were always the faceless readers on the other side of the screen. Some readers extolled, some quarrelled, and numerous others, including myself, kept lurking. In summer 2008, the Great Sichuan Earthquake killed nearly 90,000, including thousands of children buried under shoddy public school buildings. Within a couple of weeks, led by Luo Yonghao, “Bulloggers” organized its own disaster relief initiatives and received 2.4 million RMB (then about 400 thousand USD) donation from its reader-base scattered across China. As Bullog marshalled massive civic support, it also came under attack on many sides for relentlessly demanding government accountability in school construction work and for pushing back against the patriotic fervour sweeping the country at the time. This was one of the highlights of China’s so-called “liberal dissent” that had been blossoming online. What increasingly troubled me was the gap between my personal observations and the academic vocabulary that I had newly acquired. The dominant framework in the Anglophone research literature over Chinese politics and digital media, much informed by mainstream American political science, was one that juxtaposed liberal resistance with authoritarian rule. It focused on how people use the internet to criticize and protest. Left out were questions so prominent on my mind: Where did the protesters come from? How did they develop their dissent? The Chinese online world was a vast restless landscape of self-complacency, genuine confusion, existential exasperation, and tragic posturing of the lone enlightened thinker. What truly fascinated me was instead the emergence of discontent in a cultural/media environment instituted to hinder it. In hindsight, the issue boils down to how perceptions of a regime’s illegitimacy may grow in a population. After I arrived in the US for Ph.D. in 2008—during the Beijing Olympics—the puzzle began to expand. What constituted dissent in China in the first place? In mainstream political science, attention to nonliberal regimes focuses primarily on factors and forces fostering formal democratization. This agenda contrasts sharply with critical theories (emergent in liberal democracies) that explicate how liberalism and neoliberalism ideologically underpin forms of oppression and exploitation. In fact, similar tensions underlay much of the intellectual debates within China since the 1990s, known as the “right vs. left” opposition between “liberal-rightists” (e.g., many Bulloggers) and the so-called “neo-leftists.” These labels were profoundly confusing, because in post-reform, post-socialist China, being “leftist” was not perceived as radical, but as conservative, for its association with the Maoist politics of the past. The Chinese right, in turn, inherited the legacy of being persecuted under Mao. Being “rightist” was not equated with conservatism—as in clinging to traditional Chinese values such as Confucianism—but with political dissention critical of the current regime of Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But what really divided the Chinese right and left? On the one hand, the ways in which contemporary China narrated Maoist politics were passed onto the contemporary Chinese leftist position. Was it about supporting powerful state apparatuses, economic egalitarianism, the disregard for formal procedures, or some combination of each? In the eyes of their critics, Chinese (neo-)lefts were complicit with authoritarianism. On the other hand, claiming to “speak truth to power,” the Chinese liberal-rightists targeted the party-state as the embodiment of power. The leftists accused them of propagating ideas that ultimately served the interests of capital, abandoning social groups already marginalized in China’s economic reforms, which were orchestrated by none other than the current regime. Indeed, I saw strands of liberal ideas, including market fundamentalism, circulate among many Bulloggers. Mapping Chinese Disagreements No singular line of division defined the purported left-right antagonism in China. But both sides strategically downplayed the latent multidimensionality in order to denounce each other. This resembled the level of complexity in political ideologies that is taken for granted for studying liberal democracies. In China, as in other societies, no popular struggles can play out without enacting the local ideological magnetism and rhetorical devices. In fact, China’s lack of institutional consolidation of partisan division through voting, political organization, education, and media might make ideological articulations even more fluid. In the early 2010s, an opportunity led me away from the vertigo of convoluted intellectual debates to think about where ordinary web users stand amidst a constantly morphing Chinese web. Some folks created a Chinese version of the Political Compass quiz. In absence of cultures and institutions formed around partisan politics, but with a raucous web filled with ideational conflicts, people resorted to this online quiz to understand their own political positioning. Between 2008 and 2011, hundreds of thousands of Chinese took it out of curiosity. In a country where formal survey design was highly policed and survey responses unreliable due to fear and discomfort, this immense cumulation of anonymous answer sheets regarding 50 ideational statements were invaluable. They recorded what an individual simultaneously agrees and disagrees about, which in aggregation can be used to map, bottom-up, the “indigenous” political belief system. My analysis found that, in the popular mind, while statements reflecting political liberalism (e.g., it’s OK to make jokes about state leaders) tended to come with those of cultural liberalism (e.g., supporting gay marriage), none of these had a systematic alignment with economic liberalism (e.g., opposing certain government subsidies). This is not surprising given China’s lack of education and political socialization on abstract principles guiding economic policymaking. This also means that among its broad online population, unlike within intellectual discourse, views about the economy were yet to become a prominent factor informing their political positioning. The data shows that, between 2008 and 2011, the popular line of division was not even views about the political system. Instead, it was about whether one was for the vision of China rising to be a global superpower, something not aligning neatly with the intellectual left-right division. In other words, it is fair to say that a significant portion of Chinese web users had formed their opinions in ways that systematically rejected this aggressive nationalist craving. Such a rejection came with an embrace of plural cultural values and critical views of the political system. This was confirmed by my oral history interviews of Bullog readers. A large portion of my dissertation (2014) explored their changing subjectivities—how they groped their way out of nationalism over time. Much of this transformation hinged not on political values per se, but on them acquiring folk theories about the power of media environments in moulding one’s existing thinking. Many developed a paranoia of having been brainwashed, in sharp contrast to our broader climate where calling one’s opponents “brainwashed” is commonplace. Regime Legitimacy as Shifting Perceptions The Chinese government banned Bullog in early 2009, the same year that Weibo, China’s much-larger-than-Twitter platform, was launched. With technical features enabling unprecedentedly wide and swift public participation, Weibo in its beginning years was expected to further augment “liberal dissent” in China. In the summer of 2011, amid its fast growth, the propaganda department called to better “guide online opinion.” Additional to targeted censorship, this push leaned much on mobilizing government agents and legacy media outlets to encourage and amplify desirable content on Weibo. Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012. Toward the mid-2010s, China scholars and observers alike began to note a broad waning of online protests. What makes the Chinese party-state legitimate? Plenty has been written with a focus on the CCP’s official claims and China’s historical, structural propensity (e.g., the government's economic performance was the last resort when neither a charismatic leader like Mao Zedong, nor a genuine socialist conviction, remained alive). Yet ultimately, it comes down to how ordinary Chinese conceive these issues. If emerging dissent amounts to growing perceptions of regime illegitimacy, the observed conservative turn of China’s online cultures may boil down to changing perceptions about what constitutes regime legitimacy. These perceptions exemplify how people experience and evaluate the regime—I call them “regime imaginaries.” One way to explore regime imaginaries is to investigate how tizhi is popularly spoken of. Tizhi is an umbrella-concept difficult to concretize. Its dictionary definition is ‘form and structure, system (of government, etc.).’ Today, tizhi often invokes some aspects of Chinese establishments. The term’s extraordinary breadth, ambiguity, and opacity effectively alludes to party-state’s fraught roles in national politics, culture, and social life, which distinctly characterizes China’s sociopolitical configuration. When people talk about tizhi, what are they talking about? Coexisting ‘regime imaginaries’ are discernible from analysing massive amounts of Weibo posts containing tizhi to identify recurring semantic contexts surrounding the term. Analysing datasets from 2011 and 2016 respectively, changes were also evident. First, the most prevalent regime imaginary in 2011—let us call it “Critical-Reform”—attributed various social ills accompanying China’s economic reform to the regime’s negligence and incompetence in governance. In 2016, vocabularies used in Critical-Reform broke down to formulate two discrete imaginaries focused on governance over economic and judiciary matters, respectively. With this change, the permeating sense of crisis and urgency for structural overhaul had waned, and in its place emerged specific issues to be addressed professionally and bureaucratically. Second, another major regime imaginary in 2011—which can be called “Liberal-Democracy” reflected a critique of Chinese regime legitimacy according to Western liberalism. Unlike Critical-Reform, Liberal-Democracy harboured a rejection of the existing party-state system. In 2016, many of its vocabularies, such as “liberty” and “democracy,” were absorbed by the most predominant regime imaginary that I call “Civilizational-Competition.” These terms were simultaneously discredited, as Civilizational-Competition was about revelations about Western hypocrisy and calls for national solidarity. Also entailed was pride over traditional cultures and suspicion of global capitalism. In the Civilizational-Competition imaginary, the regime at once represents and protects China's prowess. Moreover, this imaginary resulted from populist sentiments, because it dominated the semantic landscape of individual user accounts on Weibo, much more than that of organizational accounts. In short, under the Xi Administration, the two legitimacy-challenging imaginaries—Critical-Reform and Liberal-Democracy—morphed drastically in five-year’s time. On the one hand, interconnected social conflicts became pigeonholed into domains of law and administration. On the other, the liberal democratic persuasions crumbled as the sense of foreign (Western) threats heightened. Characterizing the general trends at China’s political and ideological conjuncture, the discursive landscape in 2016 was much more in the regime’s favour. Coda Cut to 2020, the year Covid-19 and xenophobic populism ravaged China and the rest of world. Like the Great Sichuan Earthquake of 2008, the pandemic created a moment of national crisis and in its wake sweeping waves of patriotism. Courageous individuals again emerged, with support from numerous strangers online, contending that patriotic mobilization could be blinding and oppressive. But Bullog is long gone. And there are no similar hubs for comradery and coordination, toward which alternative voices can gravitate. At any rate confidence in the current political system is peaking. But this is not solely an outcome of authoritarian coercion and censorship. It should be clear by now that in Chinese popular imaginations regime support is intricately entwined with nationalist sentiments and impressions of Western democratic systems. Already evident in 2016, the crumbling of liberal democratic ideals boosted favourable perceptions about regime legitimacy. What 2020 witnessed in the US and other Western countries, especially through the relay of Chinese media field, further hollowed domestic visions of liberal democratic rule as a viable, let alone desirable, option. Meanwhile on the Chinese web, quite a few erstwhile prominent Bulloggers, together with many other Chinese liberal-rightist intellectuals, openly cheer for Trumpism and deride U.S. public policies that address social justice. The human rights lawyer once enamoured on Bullog, Chen Guangcheng, who in 2012 escaped to the US from state persecution, urged US citizens to vote for Trump to “stop CCP aggression.” Luo Yonghao, Bullog’s founder and once my GRE coach, became a tech entrepreneur manufacturing smartphones in the early 2010s, and then, after his business failed in 2019, joined legions of celebrities to live stream and sell goods, which were worth hundreds of millions of RMB at a time. In shifting global geopolitics, continuing capitalist perversion, and our desperate search for transnational solidarity, the Chinese dissent cannot be assumed as the purported “liberal resistance” to authoritarianism, cannot be delegated to persons of heroic deeds, and cannot be pinned down to any binary framework. What we need is sustained attention to how popular political discourses warp, how some convictions become cozy together while repelling others, and how these changing formations relate to larger structures of power. by Ico Maly

We are all living algorithmic lives. Our lives are not just media rich, they increasingly take place in and through an algorithmically programmed media landscape.[1] Algorithms, as a result of digitalisation and the de-computerisation of the internet, are ubiquitous today. We use them to navigate, to buy stuff, to work from home, to search for information, to read our newspaper and to chat with friends and even people we never met before. We live our social lives in post-digital societies: societies in which the digital revolution has been realised.[2] As a result, algorithms have penetrated and changed almost every domain in those societies.

Algorithms have become a normal and to a large extent invisible part of our world. Hence they are rarely questioned. Only when big issues erupt—think about Facebook’s role in Trump’s election, the role of conspiracy theories in the raid on Capitol, or content moderation failures— do debates on the role of digital platforms and their algorithms become prominent. Otherwise, they just seem to be “there”, just as the old media is part of our lives. As Barthes eloquently argued, normality is always a field of power.[3] Normality and normativity, he argued, are not neutral or non-ideological. On the contrary, they are hegemonic. Other ideologies and normativities are measured against this ideological point zero.[4] We could expand his logic and argue that digital platforms, their algorithms, and the ideologies that are embedded in them are part of the invisible and self-evident systemic core organising daily life. Just because we fail to recognize those algorithms and platforms as ideologically grounded, it is necessary to examine and study the impact of this algorithmic revolution in general, and its impact on politics—and the production and distribution of ideology—in particular. Ideology and the algorithmic logic of post-digital societies Digitalisation and algorithmic culture have rapidly reshuffled the media system and the information flows and interactions within that system. Politicians, activists, journalists, intellectuals and common citizens politically engage in a very different context than in the 1990s, let alone the 1950s. We now live with an algorithmically-powered attention-based hybrid media system.[5] The different types of media—newspapers, television, radio, and social media platforms—do not merely coexist, but form a media system that is constantly changing. That perpetual change is, according to Chadwick, the result of the reciprocal actions and interactions between those different media and their media logics. In that new media system, the distinction between “old” and “new” media or digital and non-digital media has almost become non-existent. Tweets become news and the newspaper tweets. Moreover, the newspaper is also more and more algorithmically produced.[6] All media in this hybrid media system are increasingly grounded in an algorithmic logic.[7] Our interactions with algorithms determine which information becomes visible to whom and on which scale. Algorithms, datafication, and the affordances of digital media that allowed for the democratisation of transmission and the banalisation of recording disrupt the status quo. We cannot understand the rise of Trump and Trumpism, or the rise of Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the Squad without taking this new media environment into account. While we should carefully avoid the trap of technological determinism, we cannot disregard the importance of including this new socio-technological context in our analysis of ideology and political discourse in contemporary societies.[8] Post-digital societies create new possibilities and constraints for the production and circulation of discourse. New producers and new relationships have been established between the different actors in this media system and they have had fundamental effects on the construction and circulation of (meta-)political messages and meanings. In the last two decades, the digital infrastructure has become an inherent part of the social fabric of society. It is one of the deep, generic drivers of concrete human behaviour in hypermediated societies.[9] Without attention to this social structure, one risks the fallacy of internalism, as J.B. Thompson called it.[10] With this concept, Thompson pointed to the widespread idea that the meaning of a text is only to be found in the text itself (and thus not in the attribution of meaning through the uptake and reproduction of texts). He stressed that ‘the analysis of ideology in modern societies must give a central role to the nature and impact of mass communication’, and argued that cultural experience is profoundly shaped by the diffusion of symbolic forms distributed through mass media.[11] As a result, the study of ideology should—if one wants to avoid the fallacy of internalism—be focused on all three aspects of mass communication: ‘the production/transmission, construction, and reception/appropriation of media messages’.[12] If we follow Thompson’s argument, we should at least direct some attention to the algorithmic nature of the distribution of discourse and ideology in contemporary societies. Algorithmic culture and the attention-based media system It is important to note here that algorithms are much more than mere technological instruments. They are socio-technical assemblages. Algorithms only work if they are fed with data. In other words, algorithms should be understood from a relational perspective. Not only do programmers (their values and their companies’ goals) matter, but also the interfaces, the data structures, and what people do with algorithms deserve our attention. The idea—so prevalent in public debate—that algorithms just do things and that users do not have impact is false. The recommended videos on YouTube are the result of the interactions between the recommendation algorithms of YouTube, viewers, and how producers prepare their content for uptake. Algorithmic culture matters. People will try to optimise their content, link to each other, have a network of fans which they ask to share content, or even have bots to push certain content. Algorithms and people have agency. It is in the interaction between humans and algorithms that the contemporary production and circulation of ideology should be understood. When we take the assumption on board that algorithms have agency, then it is important to understand the socio-technical but also the economic context in which they are created. The objectives of the platforms are clear. Beneath all the fine talk of big tech boasting about ‘connecting the world’ and ‘doing no evil’ lies the quest for profit. Social platforms make profit by commodifying our digitally networked social relationships: our emotions, photos, posts, shares and likes are repackaged into ‘tradable commodities’.[13] Or more concretely, data is used to predict the likelihood that certain audiences will be receptive or give attention to certain messages from companies or politicians. The more data those companies have about their users, the more accurately they think that sellers can target them and the more profit big tech can extract from that behavioural data. The result is an unbridled surveillance and datafication. Even if users don’t post or like and don’t leave comments, they still produce data that can be processed and traded. In order to gather more data on their users, digital media platforms nurture a specific culture in which audience labour takes a central place.[14] We have all become prosumers: we do not only consume information, we also produce it.[15] This has crucial consequences: information—including good quality information—is now abundant. It is no longer a scarce commodity. A wealth of information creates a lack of attention. We have ended up in the opposite of an information economy: an attention economy. In order to convert that attention into profit, attention is codified and categorised. The like, the comment, the view, the click, the share function as proxies of attention.[16] The digital infrastructures of the attention economy are not only organised to keep the users hooked, they facilitate audience labour and thus data production.[17] This commercial algorithmically-programmed attention economy creates a very specific environment in which we develop our social relationships. “Popularity” has become a crucial factor.[18] The more followers you have, the more likes your posts generate, the more you contribute to the goals of the platform, the more valuable you are for the platforms, and the more visible you and your discourse becomes. As a result, people increasingly present themselves as public personas in search for an audience. In order to capture the attention of platform users, we see that branding strategies have been democratised.[19] People create their brand in relation to the so-called vanity metrics: they monitor the likes, followers and uptake and use it to gain insight in what works, when, and why.[20] Or in other words, they try to acquire and apply algorithmic knowledge to produce attention-grabbing content.[21] The influencer or micro-celebrity is a structural ingredient of this new media environment: they help platforms in realising their goals. These new human practices are best seen as result of their interaction with the algorithms and values of that platform. The management of visibility and ideology research The algorithmic logic of this attention-based media environment forces us to understand the importance of algorithmic knowledge in the dissemination of ideologies on the rise. Not only the management of visibility, but also avoiding non-visibility as Bucher stresses is a constant worry for all actors in this media system and is thus of crucial importance for all ideological projects.[22] In line with Thompson, Blommaert argued that ideologies need to ‘be understood as processes that require material reality and institutional structures and practices of power and authority’.[23] Ideologies are thus not just a cognitive phenomenon, they have a material reality. Hence, they cannot be understood without looking at how people spread those ideas, who they address, which media they use, and how those media format the discourses. Studying ideologies in the contemporary era means not only looking at the input, but also at the uptake. Uptake here refers to (1) the fact that within the digital ecology users are not only consumers but also (re)producers of discourse, so-called prosumers; and (2) that algorithms and the interfaces of digital media play an important role in the dissemination and reproduction of ideas.[24] Uptake realises visibility. Human and non-human actors (from bots over the algorithms organising the communication on a platform) are a crucial part of any ideological and political battle. Note here that seemingly simple ‘reproduction’ actions like retweeting, reposting, liking, and sharing are not just ‘copies’ of the same discourse, but ‘re-entextualisations’: a share (and sometimes even a like depending on the algorithms of the platform) is the start of a new communication process where the initial message is now part of a new communicative act performed by a new producer who communicates to new addressees in a new type of interaction.[25] It is also a meaningful act seen from the perspective of the algorithm: a share and a comment adds to the ‘popularity’ of the post and thus can also contribute to its visibility far beyond the audiences of the people who have shared it. Digital media are thus not just intermediaries, they affect the input and the uptake.