by Gregory Claeys

Is utopianism an "ideology", in the loose sense of a coherent system of ideas, and if so where does it sit on the traditional spectrum of right-to-left ideas? Or does the "ism" merely describe a process of dreaming or speculating about ideal societies which in principle can never exist, as common language definitions usually imply? The former conception is relatively unproblematic, if too easily reduced to a psychological principle and then deemed deviant or pathological. Presuming the "ism" to imply the quest to attain or implement "utopia", however, we still encounter a vast number of often contradictory definitions, ranging from the common-language "impossible", "unrealistic", or without reasonable grounds to be supposed attainable, to "idealist" (as opposed to "realist"), to the "no-where" of Thomas More's original text, Utopia (1516), and its attendant pun, the "good place", or eutopia. Much confusion has resulted from inadequately separating these various definitions, two particular aspects of which, the non-existent/unreachable, and the realisable, are seemingly contradictory.

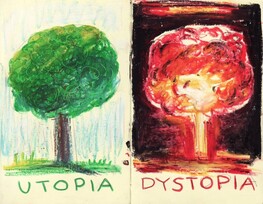

The "ism" is often divided today into three "faces", as Lyman Tower Sargent first termed them: utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice.[1] This typology is shared by another leading theorist, Krishan Kumar.[2] On this reckoning, one definition of utopian ideology would simply be utopian social theory, regardless of how we define the destination or ideal society itself, and whether it purports to be realistic or realisable, or remains an imagined ideal or norm which serves to inform action but which cannot be in principle be attained, because it continues to move forward even as its original vision comes to fruition. This approach allows us to describe every major ideology as harbouring its own utopia, or ideal type of self-realisation, while acknowledging the brand with varying degrees of reluctance. Modern liberalism, usually averse to the utopian label where it seemingly implies human perfectibility, might be supposed to entertain an ideal framed around free trade, private property, increasing opulence, and democracy.[3] Its most extreme form lies in the promise of eventual universal opulence. But it can extend further leftwards, for instance with the self-proclaimed utopian John Stuart Mill, towards socialism and much greater equality, as well as rightwards, with less state action to remedy inequality, as in libertarianism or neoliberalism.[4] Modern conservatism differs little from this, having yoked itself to commercial progress in the nineteenth century, though it sometimes retains deference to traditional elites, and greater aversion to democracy. Fascism certainly possesses utopian qualities, some rooted in the past and others in ideas of the future. Socialism inherits the Morean paradigm, with communism closer to More, and social democracy to liberalism. A specifically utopian ideology is thus more or less linked to More's paradigm of social equality, common property, substantial communal living, contempt for luxury, and a general practice of civic virtue. This can be termed utopian republicanism, and its origins traced to Spartan, Cretan, Platonic theory and Christian monastic practice.[5] Within this typology, to advert to Karl Mannheim's famous distinction in Ideology and Utopia (1936), we can also speak of utopianism having generally a critical function, and ideology a defensive one, vis-à-vis the status quo and class interest.[6] This involves a less neutral definition of ideology, not a system of ideas as such, but much closer to Marx's definition in the German Ideology (1845-6). These approaches to the utopian components in major ideologies are perfectly serviceable. They help to tease out the ultimate aspirations of systems of political ideas, as well as to reveal their whimsicalities and shortcomings. They give us a distinctive sense of More's paradigm of utopian republicanism, and of the continuity of one strand of political thought from Plato to Marx and beyond. They also reveal the more prominent role often played by fiction in the expression of utopianism compared to more overtly political ideologies. Nonetheless existing accounts of utopianism often leave us with two problems. Firstly, they do not reconcile the differences between the imaginary and realistic aspects of utopian ideals by adequately differentiating between the main functions of the concept. Secondly, they do not allow us to consider what the three "faces" share in common by way of content, or what the common goal of utopian movements, practices, and ideas alike might consist in. Let us briefly consider how these two problems might be solved.[7] Clearly ideal societies portrayed in literature and projected in social and political theory share much in common. Both are imaginary and textual, and sometimes only a thin veneer of fiction separates literary from theoretical forms of portraying ideas, particularly where "novels of ideas" are concerned. The chief definitional problem arises here from including the third, practical component. How should we categorise the content of utopian practice? That is, how do we describe what happens when people think their way of life actually approximates to utopia, rather than merely aspiring to it or dreaming of the benefits thereof? And how does this relate to the fictional and theoretical forms of utopianism? Utopian practice is usually conceived as communitarianism, or the foundation of intentional communities of mostly unrelated people who share common ideals. But it can also refer to other attempts to institutionalise the practices we associate with utopianism, most notably common or collectively-managed property, for example co-operation, or the promotion of solidarity in the workplace. Where the claim is made, we must cede to its proponents that what they practice is indeed a variant on the "good society", because they feel this is the case. That is to say, after a fashion, they have achieved, if only temporarily or conditionally, or in a relatively limited, perhaps "heterotopian", space, "utopia".[8] There is no contradiction between utopia possessing this realistic element and also implying the unrealisable if we concede that the concept serves a number of diverse purposes. It has historically had two main functions. One is to permit visionary social theory by hinting at possible futures on the basis of returning to lost or imaginary pasts, or extrapolating present trends to their logical conclusions. Once images of the Golden Age and Christian paradise served this purpose of providing an anchoring function, reminding us of what our original condition might have looked like, if for no other reason than to mock the follies and pretensions of the present and the fatuousness of any prospect of returning to a condition of natural liberty or primitive virtue. But from the late 18th century onwards utopianism began to turn towards future-oriented perfectibility, still conceived in terms of virtue, stability and social harmony, but now also more frequently linked to science and technology. So for the later modern period we can call this tendency towards imaginative projection the futurological function. By permitting us to think in terms of epochs and grand changes, the process allows us to burst asunder the bubbles of everyday life and push back the boundaries of the possible. It usually consists of one of two components. It may offer a blueprint, constitution, or programme which might actually be implemented. Or it may produce an image which allows us to criticise the present, but recedes like a mirage as we approach it, such that while we may realise past utopias we also constantly move the conceptual goal-posts, and our expectations of progress, forward. A second function of the idea of utopia is psychological, and is often addressed to explain the sources and motivation of utopian thinking. Here the concept satisfies an ingrained natural demand for progress or betterment, with which utopianism is often confused generically, and which corresponds to a personal mental space, a kind of interior greenhouse, in which the imagined improvements are conceived and nurtured. This function, associated with Martin Buber and even more Ernst Bloch, involves positing an ontological "principle of hope" or "wish-picture" where utopia functions to express a deep-seated longing for release from our anxieties.[9] This "desire" is sometimes regarded as the "essence" of utopianism.[10] This approach is often linked to religion, with which it has much in common, and in the early modern period with millenarianism in particular, and later with secular forms of millenarian thought. In Christianity both the Garden of Eden and Heaven function as ideal communities in which we participate at various levels. Our longings can be merely compensatory, alleviating the stress and anxiety of everyday life by positing a disappearance of our problems in any kind of displaced, idealised alterity. Here they may be non- or even anti-utopian, insofar as we wish our anxieties away by merely seeking distraction without social change. They may be satirical, mocking the pretensions of the wealthy and powerful. Or they may be emancipatory, demanding the alteration of reality to fit a higher ideal. This function permits escapism from oppressive everyday reality while also potentially fusing and igniting our desire for change. We can call this the alterity function, since it gives us a critical standpoint juxtaposed to our normal condition. Neither of these functions contradicts the prospect that utopia can be described as "nowhere" while also possessing a realistic dimension in communitarianism and other forms of utopian practice. They merely acknowledge the concept's multidimensional nature. This can be clarified further if we consider the problem of the content of utopianism, that is, the common normative core of the three "faces", and ask what utopian writers actually seek to realise when they actually propose restructuring society. This is easily portrayed if we remain within the loose parameters of the Morean paradigm. The existence of common property and a more communal way of life is the core of this ideal, and is shared by many forms of socialism and communism as well as many literary depictions of utopia, the best-known later modern example being Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888). Marx is of course its most famous non-literary expositor. Not all intentional communities have been communist, however. Charles Fourier, for example, proposed a reward for capitalist investors, who would receive a third, labour five-twelfths, and talent a quarter of any community's profits. Anarchist and individualist communities have sometimes promoted much less collectivist modes of organisation and social life than their socialist counterparts. But these still retain a core ideal which unites their "utopian" aspirations. All are clearly more egalitarian than the societies for which they purport to offer an alternative. They are also, or aim to be, much more closely-knit. They offer what sociologists from Ferdinand Tönnies onwards have usually referred to as a Gemeinschaft form of community, where social bonds are far stronger than in the looser and more self-interested Gesellschaft type of association which dominates everyday urban capitalist life. These more intense bonds constitute an "enhanced sociability", which epitomises utopian aspiration.[11] Normatively, utopia in general thus presents the ideal type of a much more sociable society, where something akin to friendship links many if not most of the inhabitants, and the aspiration to achieve it. But we need to give this shared content greater depth, specificity, and clarity. Not only are there many different forms of friendship, which exhibit varying degrees of solidarity, mutuality or altruism. It is readily apparent that merely consorting with others is not as such the aim of sociability. That is, we do not seek friendship, camaraderie, and other forms of intimate association and closer bonding purely for the sake of that connection, and merely out of loneliness or boredom, important though such motivations are. We aim rather at satisfying a deeper need, which can be described in terms of an elementary desire for "belongingness". This is the goal, usually conceived in terms of group membership, for which sociability is the means, and which utopian "hope" chiefly aims at. It can be described as the antidote to that alienation so often associated with the moderns, and which was at the core of the problematic the young Marx grappled with. But much of the rest of modern sociology, philosophy and political theory bears out the point. To the sociologists Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner, the "modern mind" has been described as typically a "homeless mind", a condition "psychologically hard to bear" which induces a "permanent identity crisis".[12] Buried under the blizzard of impulses modern urban life creates, moving frequently and thus often uprooted, isolated, driven apart by the dominant ethos of individualism and competition, we feel we have lost both a unity with our community and a wholeness in our inner selves. Longing to retrieve both, we search accordingly for symbolic places where we imagine we once possessed such unity. Here a Heimat - the German term evokes a richness and depth of feeling lacking in English - or "home", now lost to some other group, or just to time, easily becomes the focus of imaginary virtues, peace and fulfilment.[13] This can be projected backwards or forwards, as well as to distant locations or even outer space. Where homesickness or Heimweh lacks a definitive, objective past or place upon which to focus, it may be preferable to conceive our imaginary home as a future utopia, where Heimatslosigkeit, the feeling of loss, is conquered. If such a word existed, "homefulness" would define this domain. Another German term, Zusammengehörigkeitsgefühl, does part of the work of giving a sense of "togetherness" as well as belonging. "Belongingness" will do as well in English, and is a rich and somewhat open-ended concept which clearly invites greater scrutiny than is possible here. It enjoys a prominent position in modern group psychology, which is a key entry to point to the study of utopianism.[14] As elemental as "our need for water", Kelly-Ann Allen writes, it is so fundamental that its manifestations often passed unnoticed.[15] Some see the need to belong as the primordial source for our desire for power, intimacy, approval, and much else. It commences in infancy, drives our willingness to conform through life, and may haunt us in our dotage. It is reflected in an attachment to places as well as people, and extends by association to all our senses, including smell and taste. The sense of belonging or connectedness is a crucial component in solidarity, and is sometimes even portrayed as the basis of morality as such.[16] Everyone has experienced the anxiety of feeling alone, abandoned, ignored, friendless, rejected, shunned, dispossessed, displaced, foreign, alien, and alienated. Not being part of a group we aspire to join can be devastating. Exclusion cuts us to the bone. Not feeling part of a place also makes us uncomfortable and unwanted. By the effort to exclude others from the in-group, or "othering", belongingness can thus also play a fundamental role in the dystopian imagination.[17] So the aspiration for friendship, association, the feeling of neighbourliness, in a word belongingness, guides much of our behaviour through life. The condition of homelessness can inspire imaginary future ideal societies, and in utopian literary form has often done so during the past two centuries or so. But it also still often induces backward-looking perspectives. It "has therefore engendered its own nostalgias - nostalgias, that is, for a condition of 'being at home' in society, with oneself and, ultimately, in the universe".[18] This endangers more accurate and balanced accounts by encouraging a nostalgic rewriting of history, where we hearken back to an imagined superior past, and redact unpleasant facts which interfere with this vision. This process corresponds to an unfortunate desire, of which we have been reminded far too often in the past few years, to want to be told things which please us rather than those whose truths make us feel uncomfortable, and which we would rather ignore or forget. We are happy to be lied to if the lie makes us feel better, and rationalist conceptions of the inevitable conquest of error by truth are thus misguided where they fail to acknowledge this weakness. This process is aided by the fact that memory is often faulty and selective, and we can concoct an ideal starting-point without worrying about its accuracy. The further back we go, too, the poorer are the records which might contradict us. This makes propaganda the more readily successful. This has a bearing on one ideology more than any other. Nationalism in particular often depends heavily on and can indeed be defined as an "imagined community", in Benedict Anderson's well-known phrase, which makes it a distinctive form of utopian group.[19] It often adverts to periods when our nation was "great" and its enemies vanquished and subservient, and frequently demands a rewriting of history to accord with such narratives, as modern debates over imperialism and the statues of heroic conquerors and defenders of slavery make abundantly clear. To those not motivated by the search for more balanced stories, but who primarily seek ego reinforcement amidst their national identity crises, the glorious fictional history of the imagined nation is often preferable over its more likely inglorious and bloodstained real past. Whole nations feel a romantic nostalgia, "a painful yearning to return home", for their lost golden ages of innocence, virtue and equality, and for their mythical places of origin, or the peak of their global power and influence.[20] Denying the reality of the present and compensatory displacement are key here. But the same process occurs as nations age, become more urban and complex, and are more driven by capitalist competition, by consumerism and the anxiety to work ever harder. Personal relations suffer under all these forces. Increasingly, suggests Juliet B. Schor, we "yearn for what we see as a simpler time, when people cared less about money and more about each other".[21] Susan Stewart sees such nostalgia as a "social disease" which seeks "an authenticity of being" through presenting a new narrative, while denying the present.[22] We can readily see, then, that all major political ideologies advert to one or another glorious pasts or future images which recall or herald greater individual fulfilment, prosperity, and more powerful bonds of community. Not all address belongingness in the same manner, however. Liberalism tends from the early nineteenth century onwards to stress the value of individuality, and often under-theorises the need for and benefits of sociability.[23] Communitarian liberalism has made some effort to redress this omission, with varying degrees of success. Older forms of conservatism tended to locate the ideal state in the past and in more traditional systems of ranks, though this is not the case for more recent incarnations. Socialism is closest both semantically and programmatically to More's original utopian paradigm, and places great stress on the effort to rebuild communities around various artificially-constructed ideas of sociability and solidarity. To that inveterate critic of utopian aspiration, Leszek Kolakowski, Marxism-Leninism in particular shared a desire with all utopians "to institutionalize fraternity", adding that "an institutionally guaranteed friendship … is the surest way to totalitarian despotism", since a "conflictless order" can only exist "by applying totalitarian coercion".[24] To summarise the argument briefly presented here. What we can for short call the "3-2-1" definition of utopianism involves seeing the subject as possessing three faces or dimensions, utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice; two functions, that of providing a space of psychological alterity, and that of permitting the futurological dream of ideal societies; and one content, defined by belongingness. Utopianism is a stand-alone ideology insofar as it adopts variants on the Morean paradigm, but all major systems of ideas have utopian or ideal components which are used as reference points to suggest the goals of their systems. All forms of utopianism aim in particular at providing circumstances in which belongingness can be fulfilled. This ideal can be understood as the resolution of the central problem of alienation in modern life, an issue crucial to Marxism but equally to many other strands of modern social theory. The chief task now before us in the 2020s, to determine how it can achieve practical form in the face of the looming environmental catastrophe of the present century, can be addressed at another time. [1] Lyman Tower Sargent. Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 5. This typology dates from 1975, and is revised in Sargent's "The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited", Utopian Studies, 5 (1994), 1-37. See further Sargent's "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [2] Krishan Kumar. Utopianism (Open University Press, 1991). [3] On the aversion to adopting the utopian label, see David Estlund. Utopophobia. On the Limits (If Any) of Political Philosophy (Princeton University Press, 2020). Estlund argues that "a social proposal has the vice of being utopian if, roughly, there is no evident basis for believing that efforts to stably achieve it would have any significant tendency to succeed" (p. 11). [4] See my Mill and Paternalism (Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 123-72. [5] This typology is defended in my (and Christine Lattek) "Radicalism, Republicanism, and Revolutionism: From the Principles of '89 to Modern Terrorism", in Gareth Stedman Jones and Gregory Claeys, eds., The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 200-254. [6] See Lyman Tower Sargent. "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [7] I draw here on my After Consumerism: Utopianism for a Dying Planet (Princeton University Press, forthcoming). [8] This leaves aside the broader problem as to how far any ideal society rests on the labour or exploitation of some group(s), for whom the utopia of one group may thus become the dystopia of another. Decolonising utopia is an ongoing project. Some communes, like that founded by Josiah Warren in Ohio, have been called "Utopia". [9] See Martin Buber. Paths in Utopia, and Ernst Bloch. The Principle of Hope (3 vols, Basil Blackwell, 1986). Ludwig Feuerbach's idea of God as a projection of human desire, and of love as the essence of Christianity, formed the methodological starting-point for Marx's theory of alienation in the "Paris Manuscripts" of 1844. [10] Ruth Levitas. The Concept of Utopia (Syracuse University Press, 1990), p. 181. See also Fredric Jameson. Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (Verso, 2005). [11] An earlier version of this argument is offered in "News from Somewhere: Enhanced Sociability and the Composite Definition of Utopia and Dystopia", History, 98 (2013), 145-173. [12] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind. Modernization and Consciousness (Pelican Books, 1974), p. 74. [13] Its opposite is Heimatslosigkeit, which has no exact English equivalent, since "homefulness", sadly, is not a word and "homelessness" simply means being forced through poverty to live outside of a dwelling. Hence the use here of belongingness, despite its awkwardness. [14] It is acknowledged as such, however, chiefly in the literature on communitarianism. [15] Kelly-Ann Allen. The Psychology of Belongingness (Routledge, 2021), p. 1. [16] B. F. Skinner insists that "A person does not act for the good of others because of a feeling of belongingness or refuse to act because of feelings of alienation. His behaviour depends upon the control exerted by the social environment" (Beyond Freedom and Dignity, Penguin Books, 1973, p. 110). [17] See my Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 34-6. [18] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind, p. 77. [19] Benedict Anderson. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 1991). [20] Fred Davis. Yearning for Yesterday. A Sociology of Nostalgia (The Free Press, 1979), p. 1. [21] Juliet B. Schor. The Overspent American. Upscaling, Downshifting, and the New Consumer (Basic Books, 1998), p. 24. [22] Susan Stewart. On Longing (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), p. 23. [23] For a survey of this problem vis-à-vis John Stuart Mill, for instance, see my John Stuart Mill. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). [24] Leszek Kolakowski. Modernity on Endless Trial (University of Chicago Press, 1990), pp. 139, 143. The argument here turns largely on two assumptions, firstly that "human needs have no boundaries we could delineate; consequently, total satisfaction is incompatible with the variety and indefiniteness of human needs" (p. 138), and secondly opposition to "The utopian dogma stating that the evil in us has resulted from defective social institutions and will vanish with them is indeed not only puerile but dangerous; it amounts to the hope, just mentioned, for an institutionally guaranteed friendship". Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed