by Iain MacKenzie

Twenty years ago, the lines of debate between different versions of critically-oriented social and political theory were a tangled mess of misunderstandings and obfuscations. The critics of historicist metanarratives were often merged under the banner of postmodernism, grouped together in (sometimes surprising) couplings—postmodernism and poststructuralism, poststructuralism and post-Marxism, deconstruction and postmodernism—or strung together in a lazy list of these terms (and others) that usually ended with the customary ‘etc.’. Although this was partly the result of ‘posties’ still figuring out the detail of their respective challenges to and positions within modern critical thought, it was also a way of finding shelter together in a not altogether welcoming intellectual environment.

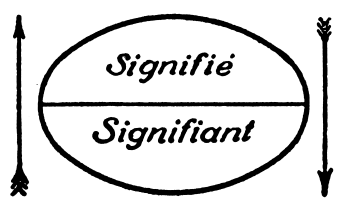

This is because it was not only the proponents of various post-isms who were unsure of what they were defending, it was also that the critics of these post-isms were indiscriminately attacking all the post-isms as one. They would cast their critical responses far and wide seeking to catch all in the nets of performative contradiction, cryptonormativism and quietism. ‘Unravelling the knots’ proposed one way of clarifying one post-ism—poststructuralism—as a small step toward inviting other posties to clarify their own position and critics to take care to avoid bycatch as they trawled the political seas.[1] That was twenty years ago: has anything changed? In many respects, yes; but not always for the better. Within the academy, taking course and module content as a rough indicator, poststructuralism has become domesticated. Once a wild and unruly animal within the house of ideas, it is now a rascally but beloved pet that we all know how to handle.[2] In political studies, this domestication has come in two ways.[3] First, it has become customary to acknowledge one’s embeddedness within regimes of power/knowledge, such that almost everyone of a critical orientation is (apparently) a Foucauldian now. Second, it has become commonplace to study discourses and how they shape identities, adding this to the methodological repertoire of political science. These two simple gestures often merit the titular rubric ‘A Poststructuralist Approach’ and yet they often remain undertheorised in the manner discussed in the original article. Often, there is neither a fully-fledged account of the emergence of structures nor an account of how meaning is constituted through the relations of difference that define linguistic and other structures. Without such in-depth accounts, we are left with empirically rich but ultimately descriptive accounts of how social forces impinge on meaning, which can have its place, or the treatment of language as a data source to be mined in search of attractive word clouds (or equivalents), which can also have its place. Whatever these claims and methods produce, however, it is not helpful to call them ‘poststructuralist’. There is still a need for the exclusive but non-deadening definition of this term, so that it is not confused with the tame house pet with which it is associated today. Part of the problem is that the discussion of how structures of meaning emerge and how they function through processes of differentiation before any dynamics of identification requires, let’s say in a Foucauldian tone, the hard work of genealogy: the patient, gray and meticulous work of the archivist combined with the lively critical work of the engaged activist.[4] But, these days, who has the patience, and the energy, for genealogy? And, in many respects, the difficulties associated with constructing intricate ‘histories of the present’ have led to a tendency to short-circuit the genealogical process (and other poststructuralist methods[5]) under the name of ‘social constructivism’. It is a shorthand, however, that has generated new entanglements, new knots, that have come to define what those of us with a long enough memory can only regret are now frequently labelled the culture wars. On one side, there are the alleged heirs of the posties, awake to the constructed nature of everything and the subtleties of all forms of oppression. On the other side, there are the new defenders of Enlightenment maturity striving to protect science from constructivism and to guard free-speech from the ‘cultural Marxists’. This epithet, of course, is the surest sign that we are in a phoney war—albeit one with real casualties—as it mimics the trawling habits of previous critics but industrialises them on a massive scale. Claims about the deleterious effects of ‘cultural Marxists’ and their social constructivist premisses simply scrape the seabed and leave it barren. But much like the debate twenty years ago, those seeking to defend ‘social constructivism’ cannot swim out of the way unless they specify that this, and other phrases like it, should never be used to end an argument. There is no use in proclaiming a social constructivism if, after all, the social itself is constructed. Shorthand is always helpful but only if we know that it is exactly that and that it will always need careful exposition and explication when critics raise the call. Moreover, what is often forgotten, in the heat of battle, is that the task is not simply to clarify one’s own claims in response to critics but to reflect upon the nature of critical exchange itself. One side of the culture wars take lively spirited debate as the signal of a flourishing marketplace of ideas. Those on the side of social construction appear to agree, simply wanting it to be a regulated marketplace of ideas. What poststructuralism brings to market is succour for neither side. Forms of critical engagement bereft of analyses of the current structures of socially mediated critical practice will always fall short of the poststructuralist project and typically dissolve into the impoverished forms of communicative exchange that never rise above the to-and-fro of opinion. It is incumbent, therefore, on poststructuralists to have a view on the nature of public interaction through social media and how these interlock with different forms of algorithmic governmentality.[6] In this way, the social constructivist shorthand can be given real critical purchase by delving deeply into the nature of public discourse and the technological forms that sustain it, particularly because these make state intervention in the name of ‘the public’ increasingly difficult (even though they can also be used, to a certain extent, for statist purposes). That said, the culture wars obfuscate a deeper misunderstanding about poststructuralism. To grasp this, however, it is important to be reminded of the overarching project of poststructuralism: it is a project aimed at completing the structuralist critique of humanism. It is important to specify this a little further. Humanism can be understood as the project of bringing meaning ‘down to earth’ so that it is in human rather than divine hands. Given this, we can articulate structuralism in a particular way: it was a series of responses to the ways in which humanism tended to treat the human being as a surreptitiously God-like entity and source of all meaning. Structuralism was the project aimed at completing the founding gesture of humanism. Poststructuralism simply recognises that there are tendencies within structuralism that similarly treat structures as analogous to God-like entities that serve as the basis of all meaning. In this respect, poststructuralism is the attempt to complete the project of structuralism, which was itself aimed at completing the project of humanism. When we understand poststructuralism in this manner it is an approach to thinking (and doing) that seeks to remove the last vestiges of enchanted, supernatural, forces, entities and explanations from all theoretical and practical activity, including science but also philosophy and the arts (broadly understood). Given this, there is no room for a pseudo-divine notion of the social that often haunts ‘social constructivism’. Indeed, given this articulation of its project, poststructuralism is hardly anti-science (as some in the culture wars might claim); rather, it is a project of understanding meaning in every respect without reinstating a source of meaning that stands ‘outside’ or ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the world that we inhabit. In fact, poststructuralists (though not all posties) are rather fond of science and they certainly do not want to undermine the natural sciences in the name of lazy ‘social constructivism’. It is, in fact, a way of seeking better science with help of philosophy, and a way of seeking better philosophy with the help of science (and for the full sense of what’s at stake, this gesture should be triangulated through inclusion of the arts). But how can there be a ‘better’ if the posties, including the poststructuralists, are sceptical of metanarratives? This question brings us to one of the more fruitful aspects that has changed in the last twenty years. The most interesting challenge faced by poststructuralists in recent times has come from the emergence of forms of neo-rationalism looking to reinvigorate critical philosophy through pragmatically oriented forms of Kantianism and non-totalising forms of Hegelianism.[7] From the neo-rationalist perspective, poststructuralism has failed in its attempts to naturalise meaning, to take it away from explanations that rely upon supernatural forces, to the extent that it is reliant upon a transcendent notion of Life that treats the priority of becoming over being as given. This immanent critique of poststructuralism cuts much closer to the bone than the Critical Theory inspired fishing which cast their nets wide but always from the harbour of their own shores. At the heart of this dispute is whether or not what we know about the world and how we know what we know about the world can be articulated within a single theoretical framework. For the neo-rationalist, it is (in principle, at least) possible to work on the assumption that there is an underlying unity between ontology and epistemology founded upon a specific conception of reason-giving. For poststructuralists, exploration of the conditions of experience suggests a dynamic distance between the what and the how, such that the task is to secure the claims of philosophy, art and science as equal routes into our understanding of both. While this reconstitutes a certain return to the pre-critical debates between rationalists and empiricists, it is equally indebted to the critical turn with respect to the shared task of legitimating knowledge claims, but with a pragmatic or practical twist. Both the neo-rationalists and the poststructuralists pragmatically assess the worth of the knowledge produced by virtue of the challenges they proffer to arguments that rely upon a transcendent God-like entity and the dominant form of this today; namely, the sense of self-identity that underpins capitalist endeavours to maximise profit. This critical perspective, perhaps surprisingly, was seeded within the fertile soil of American pragmatism. For the pragmatists—and we might think especially of Pierce, Sellars, and Dewey—it is the practical application of philosophy that engenders standards of truth, rightness and value. Admittedly, in the hands of its founding fathers, this practical application was often guided by the idea of maintaining the status quo. But that is not essential. Neo-rationalists and poststructuralists have found a shared concern with the idea that philosophical practice should be guided by the critique of capitalist forms of thought and life. As such, they share a common ground upon which meaningful discussion can be forged, aside from the culture wars (which are simply a reflex of capitalist identitarian thinking). While deep-seated divisions remain—does the knowledge generated by social practices of reason giving trump the experience of creative learning or are they on the same cognitive footing?—the shared sense of seeking a critical but non-final standard for what counts as better (better than the identity-oriented thinking sustaining capitalism) is driving much of the most productive debate and discussion at the present time. Work of this kind reminds us that poststructuralism is still a wild animal rather than a domesticated house pet, that it is a critical project but also one that has political intent. That said, it is not always easy to convey the political dimension of poststructuralism, especially given the vexed question of its relationship to ideology. As discussed in the original article, part of the initial excitement about poststructuralism was that its major figures distanced themselves from the idea of ideology critique. However, this was only ever the beginning of a complex story about the relationship of poststructuralism to ideology and never the end.[8] While Marxist notions of ideology were critiqued for the ways in which they incorporated notions of the transcendental subject, naïve versions of what counts as real and over-inflated notions of truth, poststructuralists have always endorsed the power of individual subjects to express complex notions of reality and historically sensitive and effective notions of truth, and to do so against dominant social and political formations. These formations are often given unusual names—dispositif, assemblages, discourses, and such like—but the aim of unsettling and ultimately unseating the dogmatic images and frozen practices of social and political life is not too distant from that animating Marxism. Of course, as Deleuze and Guattari expressed it, any revised Marxism needs to be informed by significant doses of Nietzscheanism and Freudianism (just as these need large doses of Marxism if they are to avoid becoming critically quietest and practically relevant for the critique of capitalism).[9] What results, though, is an immanent version of ideology critique rather than a rejection of it tout court: there are many assemblages/ideologies that dominate our thoughts, feelings and behaviour and it is possible to learn how they operate by making a difference to how they function and reproduce themselves. In searching for the natural bases of meaningful worlds it is no surprise that poststructuralists have become adept at diagnoses of how natural processes can lead to systems of meaning that import supernatural fetishes into our everyday lives, and how these are sustained in ways even beyond merely serving the interests of the economically powerful. There appear to be an endless number of these knots that need untying. If we want to untie at least some of them, then unravelling the knots that currently have poststructuralism tangled up in a phoney culture war is another small step on the road to bringing a meaningful life fully down to earth. [1] I.MacKenzie, ‘Unravelling the knots: post-structuralism and other “post-isms”’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 6 (3), 2001, pp. 331–45. [2] I. MacKenzie and R. Porter, ‘Drama out of a crisis? Poststructuralism and the Politics of Everyday Life’, Political Studies Review, 15 (4), 2017, pp. 528–38. [3] One of the interesting features of the recent history of poststructuralism is that it is not the same across disciplines. Of course, this need for disciplinary specificity with respect to how knowledge is disrupted, new forms of knowledge established and then domesticated is part of what poststructuralism offers. That said, much of what follows can be read across various disciplines in the arts, humanities, sciences and social sciences to the extent that the legacies of humanism and historicism traverse these disciplines. [4] M. Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in D. Bouchard (ed.) Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault (New York: Cornell University Press, 1992 [1971]), pp. 139–64. [5] B. Dillet, I. MacKenzie and R. Porter (eds) The Edinburgh Companion to Poststructuralism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013). [6] A. Rouvroy, ‘The End(s) of Critique: data-behaviourism vs due-process’ in M. Hildebrandt and E. De Vries (eds), Privacy, Due Process and the Computational Turn. Philosophers of Law Meet Philosophers of Technology (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 143–68. [7] See R. Brassier’s engagment with the work of Wilfrid Sellars, for example: 'Nominalism, Naturalism, and Materialism: Sellars' Critical Ontology' in B. Bashour and H. Muller (eds) Contemporary Philosophical Naturalism and its Implications (Routledge: London, 2013). [8] R. Porter, Ideology: Contemporary Social, Political and Cultural Theory (Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2006) and S. Malešević and I. MacKenzie (eds), Ideology After Poststructuralism (Oxford: Pluto Press, 2002). [9] G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (New York: Viking Press, 1977). This triangulation of the philosophers of suspicion, with a view to completing the Kantian project of critique, is one especially insightful way of reading this provocative text: see E. Holland, Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Introduction to Schizoanalysis (London: Routledge, 2002). Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed