|

21/6/2021 Fascism as a recurring possibility: Zeev Sternhell, the anti-Enlightenment, and the politics of an intellectual history of modernityRead Now by Tommaso Giordani

Examining the development of Zeev Sternhell’s work yields a precise impression: that of a movement from the particular to the general, from an intellectual history rooted in precise contexts to increasingly broad studies dealing with larger and less narrowly contextualised traditions of thought.

His first monograph, published in 1972, was titled Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français and examined the role of Barrès in transforming a French nationalism which was originally “Jacobin, open, grounded in the doctrine of natural rights” into an “organic nationalism, postulating a physiological determinism”.[1] In the decade between 1978 and 1989, Sternhell publishes the three works which created his reputation as one of the world’s most important historians of fascism: Ni droite ni gauche, La droite révolutionnaire, and Naissance de l’idéologie fasciste. Though still maintaining a focus on France, these studies—especially the last one—cannot be reduced to contributions to French history. They are instead an attempt to outline a theory of fascism centred on the importance of the ideological element, something which naturally brought the Israeli historian and his collaborators beyond the borders of the hexagon. Following this interpretative line, we can identify a third phase of Sternhell’s work starting from the 1996 collective volume The intellectual revolt against liberal democracy. Having first moved beyond the examination of French nationalism towards a more general theory of fascism, in this third phase Sternhell leaves the question of fascist ideology behind, embedding it in a larger narrative embracing the last three centuries of European intellectual history and revolving around the dichotomy between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment ideas. The high point is represented by his last and most ambitious study, Les Anti-Lumières, in which the Israeli historian traces the development of what he calls a “different modernity”, consisting in a “comprehensive revolt against the Enlightenment’s fundamental views”.[2] I. There is obviously a great deal of truth in this way of reading the Israeli historian’s trajectory, especially given the substantial growth of the materials treated and the enlargement of both chronology and geography. And yet, there is an important way in which this reading is wrong, namely if it is taken to claim that the large, meta-historical categories of “Enlightenment” and “Anti-Enlightenment” are inductive generalisations, synthesising decades of work in intellectual history and emerging from Sternhell’s previous studies. A summary look at Sternhell first book reveals, instead, that these categories have informed his work since the beginning. Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français is, as we have pointed out, not a simple intellectual biography, but a work which sees the significance of Barrès through the wider lens of a study of the transformation of French nationalism. Upon closer inspection, however, it is clear that even the framework of French nationalism is a very reductive description of Sternhell’s perspective, for it is a nationalism which is embedded in a wider current of ideas, both spatially and temporally. Spatially, Barrès participates in a tradition of thought which is continental. He is cast by Sternhell much more as a European than as a Frenchman. Barrès is “the child of his century: Baudelaire and Wagner fascinate him, he calls himself—and is—a disciple of Taine and Renan; he has read Nietzsche, Gobineau, and Dostoevsky. For his first trilogy, he claims to have been inspired by Schopenhauer, by Fichte, and by Hartmann”.[3] Temporally, this continental tradition to which Barrès belongs is cast as deploying itself over a broad chronology, as can be evinced by Sternhell’s insistence on its similarities with “another movement of revolt against the status quo: pre-1830, post-revolutionary romanticism”.[4] Without denying the decisive role of European fin de siècle culture, Sternhell finds common traits between this “neo-romanticism” and the older movement. In both cases, we have a “resurgence of irrational values”, the “cult of sentiment and instinct” and, finally, “the substitution of the ‘organic’ explanation of the world to the ‘mechanical’ one”.[5] Even if the connections are merely sketched, it is clear that the temporality in which Sternhell places his object is that of modernity. Barrès, in other words, is significant not just as a French nationalist, but as a member of a tradition marked by the “systematic rejection of the values inherited from the eighteenth century and from the French Revolution”.[6] Granted, the term “Anti-Enlightenment” does not appear in this work, and comparison of this initial sketch of the tradition with later versions yields some differences, such as a greater role he later ascribes to German and Italian historicism, as well as a tendency to read this current of ideas in an increasingly static and monolithic way. And yet, beyond these small differences, substantial similarities emerge: the broad chronology, the continental extension, and the dichotomous division of the last two centuries of European intellectual history into the two opposing camps of the Enlightenment and its enemies. II. This dichotomy informs virtually the entirety of Sternhell’s works in the history of political ideas. We see it at work in his trilogy on fascist ideology, and it is subtly yet unmistakeably active in his analysis of Zionism, in which Jewish nationalism is characterised, inter alia, as a “Herderian” response to the “challenge of emancipation”.[7] Underlying historical enquiry on particular political ideologies, in other words, is a theory of European modernity revolving around the opposition between what Sternhell came to label the universalistic “Franco-Kantian Enlightenment” and its particularistic opponents. Methodologically, the advantages of this approach are many: it allows the writing of a profoundly diachronic history of ideas, capable of embracing a multitude of contexts and spaces, and in theory able to trace the evolution of traditions of thought without losing sight of the underlying continuities. At the same time, various critics have underlined its limits. Sternhell has been accused of not having learnt the lessons of postmodernism, and of reconstructing the intellectual history of European modernity in the form of a “Manichean struggle” between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment.[8] General accusations of Manicheanism, approximation, and teleology are, in fact, amongst the most common directed against Sternhell. Shlomo Sand gives a more precise way to consider the limits of this approach, identifying the problem in Sternhell’s use of “narrow, static, unhistorical definitions”, that is, of meta-historical categories.[9] Here we come to the crux of the question: Sternhell’s way of proceeding is indeed marked by the use of categories of analysis which transcend the contexts in which historical actors developed their thought. Is this, however, enough to methodologically invalidate his analysis? The use of categories transcending narrow historical contextualisation is a necessity for any work with diachronic ambitions. Tracing the development of any tradition of thought over time, in other words, implies the use of descriptions and definitions which would have appeared bizarre to the thinkers of the time. The employment of a meta-language, and the anachronism, teleology, and de-contextualisation that come with it, are, to a point, a necessity of any genealogy, of any historical enquiry which aims to do more than simply take a synchronic snapshot of the past. Therefore, it seems incorrect to identify the problem in the mere use of categories such as Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment. The problem lies not in the mere presence of these meta-historical tools of analysis, but, rather, in the way in which Sternhell has come to employ them over time. As we have seen, in Maurice Barrès the anti-Enlightenment tradition was sketched with a certain nuance, insisting on its internal transformations over time, and paying attention to the crucial distinction between the work of an individual and its reception. Over time, however, much of this nuance disappears, and passages from his later works do seem, at times, to interpret two centuries of European intellectual history through the prism of what is, after all, a not too dynamic dichotomy between French universalistic culture and German romantic particularism. III. Take Sternhell’s analysis of Georges Sorel’s revision of Marxism at the beginning of the 20th century, for example. For the Israeli historian, it constitutes a crucial step towards the creation of fascist ideology. According to him, the key element of Sorelian revisionism is the destruction of the connection between the industrial working class and the revolution, something capable of altering “Marxism to such an extent that it immediately transformed it into a neutral weapon of war that could be used against the bourgeois order not only by the proletariat but by society as a whole”.[10] Sorelian revisionism thus consists in the removal of Marxian categories of analysis based on social antagonisms grounded in the positioning in the productive structure of society, which are then replaced by antagonisms grounded in an opposition to the decadence of bourgeois civilisation. As Sternhell puts it, “history, for Sorel, was finally not so much a chronicle of class warfare as an endless struggle against decadence”.[11] It follows that if the proletariat is unable to fulfil its struggle against bourgeois decadence, there is no reason why another historical agent, such as the national community, should not engage in the same struggle. The result is fascism. The problem with this reading is that, despite its apparent plausibility, it is historically inaccurate. Real Sorelian revisionism consists in a number of texts published in the 1890s in which the main thrust is epistemological and social scientific more than political. Its consequences are opposite to those drawn by Sternhell. Animated by the desire “show to sceptics that… socialism is worthy of belonging to the modern scientific movement”, Sorelian revisionism revolved around three main points: (1) the refusal of historical determinism; (2) the rejection of economic determinism; and consequently, (3) a vision of Marxism not as a predictive social science but as the intellectual articulation of the historical experience of the workers’ movement.[12] Even if this revisionism is much more concerned with Marxism as a social science than with Marxism as a political project, its political uptake is not the breaking of the connection between proletariat and revolution, but its strengthening. A Marxism which renounces its predictive capacity and the very idea of a necessary historical development cannot but evolve into what Sorel later called a “theory of the proletariat”. The removal of historical necessity means that the transition to socialism can only be yielded by the agency of the revolutionary subject—the proletariat. It should thus not be surprising that, as early as 1898, Sorel insists on working class autonomy, arguing that “the entire future of socialism resides in the autonomous development workers’ unions”.[13] The revision of Marxism does not exhaust Sorel’s production and there are parts of his trajectory, and of those of some of his disciples, which are more in line with Sternhell’s analysis. And yet, the fact remains that this analysis completely overlooks contexts which are crucial to Sorelian revisionism, resulting in an historically inaccurate picture. The point is not merely to underline the many substantial imprecisions which characterise Sternhell’s reading of Sorelian revisionism, but to emphasise how these misreadings derive directly from the indiscriminate use of the abovementioned meta-historical categories. “Marxism” writes Sternhell “was a system of ideas still deeply rooted in the philosophy of the eighteenth century. Sorelian revisionism replaced the rationalist, Hegelian foundations of Marxism with Le Bon’s new vision of human nature, with the anti-Cartesianism of Bergson, with the Nietzschean cult of revolt, and with Pareto’s most recent discoveries in political sociology”.[14] But is it plausible to speak of a rejection of Hegel for someone so profoundly influenced by Antonio Labriola, who represented one of Europe’s main Hegelian traditions? Is it correct to speak of the “Nietzschean cult of revolt” for a figure who wrote over 600 texts and yet discusses Nietzsche virtually only in a handful of pages in the Reflections on violence? Is it historically acceptable to suggest proximity to Paretian elitism for a political thinker who wrote vitriolic pages against the leadership of French socialism by bourgeois intellectuals? These misreadings derive from the fact that Sternhell’s dualistic approach, if taken rigidly, cannot make space for Sorelian revisionism, for that would imply accepting the possibility of a Marxism capable of incorporating elements of romanticism without ipso facto becoming a sworn enemy of the Enlightenment. But Marxism, for Sternhell, is “rooted in the philosophy of the eighteenth century”, and any deviation from this particular philosophical outlook is to be classified as anti-Enlightenment thought. Strictly speaking, for Sternhell, Sorelian revisionism is a betrayal. But here are the limits of Sternhell’s rigid application of his categories, limits which emerge not only in relation to Sorel, but also to Marxism more in general. Marxism is, from its beginnings, a politico-philosophical tradition which is transversal to the dichotomy between Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment. The mere suggestion of reading a tradition derived from Hegel and Marx as in opposition to German romanticism shows the dangers of overreliance on these categories. The appropriate historical context for understanding Sorelian revisionism is the battle, internal to Marxism, between positivistic and humanistic interpretations of Marx’s work. Against Sorel’s insistence on the impossibility of historical laws there is Lafargue who advocates their existence; against Antonio Labriola who struggles to free historical materialism from positivism there is Enrico Ferri who goes in the opposite direction. To miss this transversality of the Marxist tradition cannot but yield serious mistakes. How would Sternhell judge Gramsci’s claim that Marxism is “the continuation of German and Italian idealism, which in Marx had been contaminated by naturalistic and positivistic incrustations”? Would he see a voluntaristic cult of revolt in the affirmation that “the main determinant of history is not lifeless economics, but man”?[15] IV. Why, in the face of much criticism, did Sternhell never even go close to admitting the risks of a certain way of employing an approach based on meta-historical categories? Why did he not only stick with it, but began using it in an increasingly rigid and passionate manner? To answer these questions, a preliminary point must be clarified. If the Enlighenment/anti-Enlightenment dualism is the conceptual centre of Sternhell’s work, its existential core is the question of fascism. Orphaned and turned refugee by anti-Semitic violence in his native Poland during World War II, Sternhell has always been very clear on the fact that for him the study of fascism went far beyond purely academic interest. Anyone who has read the pages he has written will be aware of the urgency of his prose, of the passionate tone of warning which permeates most of them, especially those on fascism. “Thinking about fascism” he wrote in 2008 “is not a reflection on a regime or a movement, but a reflection on the risks that might be involved for a whole civilisation when it rejects the notion of universal values, when it substitutes historical relativism for universalism, and substitutes various communitarian values for the autonomy of the individual”.[16] Aside from clarifying the relationship between fascism and anti-Enlightenment in Sternhell’s thought—with the former political option becoming possible only in an environment in which the latter’s ideas are present—this quotation sheds much light on Sternhell’s insistence on the Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment duality. To frame fascism as a political possibility enabled by the existence of certain anti-Enlightenment ideas means adopting a view of fascism as a recurring possibility of modernity. Fascism is thus not an abstract and a-historical ideal type, but neither is it an historical particularity inextricably linked to the specific, and unrepeatable, conditions of interwar Europe. To embed fascism in a theory of modernity, in other words, allows one to see it as a living political culture, perhaps at times dormant, but constantly capable of making the leap from cultural contestation to political project, at least as long as the particularistic ideas of the “alternative modernity” of the anti-Enlightenment continue to inform European intellectual life. Sternhell’s dismissal of the decisive role of World War I and his insistence that the fascist synthesis was already achieved in the belle époque substantiate this reading. The Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment framing, in short, stems from the fiercely held conviction that fascism is not a thing of the past, but of the present. It is a framing, thus, that at once emerges from the need for public engagement and simultaneously enables a mode of public intervention which could not as easily be sustained through a narrower contextualism or a taxonomical approach. Recent years have brought, together with the electoral victories of right-wing forces in Europe and the United States, a flurry of analyses on the return of fascism. Whether through taxonomies, historical parallels between the present and the interwar period, or analyses of fascist mentality, this literature has been animated by the same conviction that has long animated Zeev Sternhell’s work: that fascism is not a thing of the past. Eschewing these strategies, however, Sternhell has long pioneered a different way of thinking about fascism: not an historical particularity, not a mentality, not a list of criteria that regimes must possess, but instead a constant potentiality of European modernity, embedded in two centuries of anti-Enlightenment thought. By way of conclusion, a tentative answer to the obvious question: from where does Sternhell’s conviction that fascism is always possible emerge? It is true that the defeat of 1945 has not been the historical caesura one unreflectively imagines, and that fascism has continued to exist, in less ideologically assertive forms, in many countries of southern Europe. At the same time, before the recent, possibly short-lived, resurgence of the fascist spectre, academic analyses of fascism were rarely animated by this urgent conviction of its relevance. The answer to this conundrum is to be found in Sternhell’s political engagement in his country, Israel. In March 1978, together with other reservists of the Israeli army, Sternhell signed an open letter to then Prime Minister Menachem Begin, warning that a policy “which prefers settlements beyond the Green Line to terminating the historic conflict” was a dangerous one, which could “harm the Jewish-democratic character of the state”.[17] The letter established the organisation Peace Now, in which Sternhell continued to be active for the rest of his life. Over the years, the evolution of the political situation made the positions Sternhell supported increasingly minoritarian. But the Israeli historian did not back down. On the contrary, he continued to put forward his positions. This earned him a pipe bomb attack at his home in Jerusalem in 2008, from which he emerged substantially unscathed. Flyers offering over 1 million shekels to whoever killed a member of Peace Now found near his home left little doubt as to the motivations behind it. After Benjamin Netanyahu became prime minister in 2009, Sternhell became increasingly vocal, denouncing what he saw as a dangerous evolution of Israeli society. In his many public interventions, he uses the language with which we have been dealing here, that of the anti-Enlightenment. He saw the rise of the Israeli right as that of a “power-driven national movement, negating human rights, and rejecting universal rights, liberalism and democracy”.[18] In a 2014 interview in which he denounced signs of fascism in Israeli society, he framed that political option in familiar terms: as a “war against enlightenment and against universal values”.[19] In 2013, he was called as an expert witness in a defamation case put forward by the nationalist association Im Tirzu against some activists who had labelled it as fascist. In an exchange with Im Tirzu’s lawyer, we see, again, the same language: “…they are not conservatives, but revolutionary conservatives. What they seek is a cultural revolution. ‘Neo-Zionism’ as they define it is an anti-utilitarian, anti-western, anti-rational cultural revolution.”[20] Examples of this kind could be multiplied, but the point should by now be clear. Certain methodological options may seem puzzling when judged uniquely by the standards of academic practice, but the rationale for their employment may become more understandable when they are seen as connected to a concrete historical situation. The Enlightenment/anti-Enlightenment dichotomy, with all the limits that Sternhell’s passionate use involved, is one such case: it must, at least partially, be seen as emerging from the imperative of engagement. Still, Sternhell’s historical works are not political pamphlets. Even if sometimes they possess the urgent tone of that genre of writing, they remain contributions to the study of European intellectual history, and should be judged also according to those standards. And yet, the separation of these two layers, engagement and scholarship, is not easy and, to a point, not desirable. To effect this separation would be to misunderstand the work of a scholar for whom the two were intertwined. As he argued in the most articulate defence of his method, “through contextualism, particularism, and linguistic relativism, in concentrating on what is specific and unique and denying the universal, one necessarily finds oneself on the side of anti-humanism and historical relativism”.[21] The author would like to thank Or Rosenboim for discussions on the Israeli context and for help with translations from Hebrew. All other translations from French and Italian sources are the author's. Research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under Grant Agreement No. 757873 (project BETWEEN THE TIMES). [1] Zeev Sternhell, Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français [1972], 3rd ed. (Paris: Fayard, 2016), 251. [2] Zeev Sternhell, The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition, trans. David Maisel (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 1. [3]Sternhell, Maurice Barrès, 56. [4] Ibid., 42. [5] Ibid., 43. [6] Ibid., 41. [7] Zeev Sternhell, The Founding Myths of Israel. Nationalism, Socialism, and the Making of the Jewish State, trans. David Maisel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 12. [8] David D. Roberts, ‘How not to think about Fascism and ideology, intellectual antecedents and historical meaning’, Journal of Contemporary History 35, no. 2 (2000): 189. [9] Shlomo Sand, ‘L’idéologie Fasciste en France’, L’Esprit, September 1983, 159. [10] Zeev Sternhell, Maia Asheri, and Mario Sznajder, The Birth of Fascist Ideology. From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution., trans. David Maisel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 37. [11] Ibid., 38 [12] Sorel to Croce, 20/12/1895, in Georges Sorel, ‘Lettere di Georges Sorel a Benedetto Croce’, La Critica 25 (1927): 38. [13] Georges Sorel, ‘L’avenir socialiste des syndicats’, L’humanité Nouvelle 2 (1898): 445. [14] Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology, 24. [15] Antonio Gramsci, ‘La rivoluzione contro il Capitale’, Avanti! 24 November 1917. [16] Zeev Sternhell, ‘How to Think about Fascism and Its Ideology’, Constellations 15, no. 3 (2008): 280. [17] Open letter to Prime Minister Menachem Begin, March 1978, https://peacenow.org/entry.php?id=2230#.YK5yjKGEY2w [18] Zeev Sternhell “Does Israel still need democracy”, Haaretz, 17 November 2011 [19] Gidi Weitz, ‘Signs of fascism in Israel reached new peak during Gaza op, says renowned scholar’, Haaretz, 13 August 2014. [20] Oren Persico, “Analyzing with an ax”, Ha-ain ha-shvi’it, 12 May 2013, https://www.the7eye.org.il/62652 [21] Sternhell, The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition, 35. by Gregory Claeys

Is utopianism an "ideology", in the loose sense of a coherent system of ideas, and if so where does it sit on the traditional spectrum of right-to-left ideas? Or does the "ism" merely describe a process of dreaming or speculating about ideal societies which in principle can never exist, as common language definitions usually imply? The former conception is relatively unproblematic, if too easily reduced to a psychological principle and then deemed deviant or pathological. Presuming the "ism" to imply the quest to attain or implement "utopia", however, we still encounter a vast number of often contradictory definitions, ranging from the common-language "impossible", "unrealistic", or without reasonable grounds to be supposed attainable, to "idealist" (as opposed to "realist"), to the "no-where" of Thomas More's original text, Utopia (1516), and its attendant pun, the "good place", or eutopia. Much confusion has resulted from inadequately separating these various definitions, two particular aspects of which, the non-existent/unreachable, and the realisable, are seemingly contradictory.

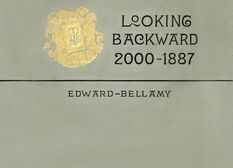

The "ism" is often divided today into three "faces", as Lyman Tower Sargent first termed them: utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice.[1] This typology is shared by another leading theorist, Krishan Kumar.[2] On this reckoning, one definition of utopian ideology would simply be utopian social theory, regardless of how we define the destination or ideal society itself, and whether it purports to be realistic or realisable, or remains an imagined ideal or norm which serves to inform action but which cannot be in principle be attained, because it continues to move forward even as its original vision comes to fruition. This approach allows us to describe every major ideology as harbouring its own utopia, or ideal type of self-realisation, while acknowledging the brand with varying degrees of reluctance. Modern liberalism, usually averse to the utopian label where it seemingly implies human perfectibility, might be supposed to entertain an ideal framed around free trade, private property, increasing opulence, and democracy.[3] Its most extreme form lies in the promise of eventual universal opulence. But it can extend further leftwards, for instance with the self-proclaimed utopian John Stuart Mill, towards socialism and much greater equality, as well as rightwards, with less state action to remedy inequality, as in libertarianism or neoliberalism.[4] Modern conservatism differs little from this, having yoked itself to commercial progress in the nineteenth century, though it sometimes retains deference to traditional elites, and greater aversion to democracy. Fascism certainly possesses utopian qualities, some rooted in the past and others in ideas of the future. Socialism inherits the Morean paradigm, with communism closer to More, and social democracy to liberalism. A specifically utopian ideology is thus more or less linked to More's paradigm of social equality, common property, substantial communal living, contempt for luxury, and a general practice of civic virtue. This can be termed utopian republicanism, and its origins traced to Spartan, Cretan, Platonic theory and Christian monastic practice.[5] Within this typology, to advert to Karl Mannheim's famous distinction in Ideology and Utopia (1936), we can also speak of utopianism having generally a critical function, and ideology a defensive one, vis-à-vis the status quo and class interest.[6] This involves a less neutral definition of ideology, not a system of ideas as such, but much closer to Marx's definition in the German Ideology (1845-6). These approaches to the utopian components in major ideologies are perfectly serviceable. They help to tease out the ultimate aspirations of systems of political ideas, as well as to reveal their whimsicalities and shortcomings. They give us a distinctive sense of More's paradigm of utopian republicanism, and of the continuity of one strand of political thought from Plato to Marx and beyond. They also reveal the more prominent role often played by fiction in the expression of utopianism compared to more overtly political ideologies. Nonetheless existing accounts of utopianism often leave us with two problems. Firstly, they do not reconcile the differences between the imaginary and realistic aspects of utopian ideals by adequately differentiating between the main functions of the concept. Secondly, they do not allow us to consider what the three "faces" share in common by way of content, or what the common goal of utopian movements, practices, and ideas alike might consist in. Let us briefly consider how these two problems might be solved.[7] Clearly ideal societies portrayed in literature and projected in social and political theory share much in common. Both are imaginary and textual, and sometimes only a thin veneer of fiction separates literary from theoretical forms of portraying ideas, particularly where "novels of ideas" are concerned. The chief definitional problem arises here from including the third, practical component. How should we categorise the content of utopian practice? That is, how do we describe what happens when people think their way of life actually approximates to utopia, rather than merely aspiring to it or dreaming of the benefits thereof? And how does this relate to the fictional and theoretical forms of utopianism? Utopian practice is usually conceived as communitarianism, or the foundation of intentional communities of mostly unrelated people who share common ideals. But it can also refer to other attempts to institutionalise the practices we associate with utopianism, most notably common or collectively-managed property, for example co-operation, or the promotion of solidarity in the workplace. Where the claim is made, we must cede to its proponents that what they practice is indeed a variant on the "good society", because they feel this is the case. That is to say, after a fashion, they have achieved, if only temporarily or conditionally, or in a relatively limited, perhaps "heterotopian", space, "utopia".[8] There is no contradiction between utopia possessing this realistic element and also implying the unrealisable if we concede that the concept serves a number of diverse purposes. It has historically had two main functions. One is to permit visionary social theory by hinting at possible futures on the basis of returning to lost or imaginary pasts, or extrapolating present trends to their logical conclusions. Once images of the Golden Age and Christian paradise served this purpose of providing an anchoring function, reminding us of what our original condition might have looked like, if for no other reason than to mock the follies and pretensions of the present and the fatuousness of any prospect of returning to a condition of natural liberty or primitive virtue. But from the late 18th century onwards utopianism began to turn towards future-oriented perfectibility, still conceived in terms of virtue, stability and social harmony, but now also more frequently linked to science and technology. So for the later modern period we can call this tendency towards imaginative projection the futurological function. By permitting us to think in terms of epochs and grand changes, the process allows us to burst asunder the bubbles of everyday life and push back the boundaries of the possible. It usually consists of one of two components. It may offer a blueprint, constitution, or programme which might actually be implemented. Or it may produce an image which allows us to criticise the present, but recedes like a mirage as we approach it, such that while we may realise past utopias we also constantly move the conceptual goal-posts, and our expectations of progress, forward. A second function of the idea of utopia is psychological, and is often addressed to explain the sources and motivation of utopian thinking. Here the concept satisfies an ingrained natural demand for progress or betterment, with which utopianism is often confused generically, and which corresponds to a personal mental space, a kind of interior greenhouse, in which the imagined improvements are conceived and nurtured. This function, associated with Martin Buber and even more Ernst Bloch, involves positing an ontological "principle of hope" or "wish-picture" where utopia functions to express a deep-seated longing for release from our anxieties.[9] This "desire" is sometimes regarded as the "essence" of utopianism.[10] This approach is often linked to religion, with which it has much in common, and in the early modern period with millenarianism in particular, and later with secular forms of millenarian thought. In Christianity both the Garden of Eden and Heaven function as ideal communities in which we participate at various levels. Our longings can be merely compensatory, alleviating the stress and anxiety of everyday life by positing a disappearance of our problems in any kind of displaced, idealised alterity. Here they may be non- or even anti-utopian, insofar as we wish our anxieties away by merely seeking distraction without social change. They may be satirical, mocking the pretensions of the wealthy and powerful. Or they may be emancipatory, demanding the alteration of reality to fit a higher ideal. This function permits escapism from oppressive everyday reality while also potentially fusing and igniting our desire for change. We can call this the alterity function, since it gives us a critical standpoint juxtaposed to our normal condition. Neither of these functions contradicts the prospect that utopia can be described as "nowhere" while also possessing a realistic dimension in communitarianism and other forms of utopian practice. They merely acknowledge the concept's multidimensional nature. This can be clarified further if we consider the problem of the content of utopianism, that is, the common normative core of the three "faces", and ask what utopian writers actually seek to realise when they actually propose restructuring society. This is easily portrayed if we remain within the loose parameters of the Morean paradigm. The existence of common property and a more communal way of life is the core of this ideal, and is shared by many forms of socialism and communism as well as many literary depictions of utopia, the best-known later modern example being Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888). Marx is of course its most famous non-literary expositor. Not all intentional communities have been communist, however. Charles Fourier, for example, proposed a reward for capitalist investors, who would receive a third, labour five-twelfths, and talent a quarter of any community's profits. Anarchist and individualist communities have sometimes promoted much less collectivist modes of organisation and social life than their socialist counterparts. But these still retain a core ideal which unites their "utopian" aspirations. All are clearly more egalitarian than the societies for which they purport to offer an alternative. They are also, or aim to be, much more closely-knit. They offer what sociologists from Ferdinand Tönnies onwards have usually referred to as a Gemeinschaft form of community, where social bonds are far stronger than in the looser and more self-interested Gesellschaft type of association which dominates everyday urban capitalist life. These more intense bonds constitute an "enhanced sociability", which epitomises utopian aspiration.[11] Normatively, utopia in general thus presents the ideal type of a much more sociable society, where something akin to friendship links many if not most of the inhabitants, and the aspiration to achieve it. But we need to give this shared content greater depth, specificity, and clarity. Not only are there many different forms of friendship, which exhibit varying degrees of solidarity, mutuality or altruism. It is readily apparent that merely consorting with others is not as such the aim of sociability. That is, we do not seek friendship, camaraderie, and other forms of intimate association and closer bonding purely for the sake of that connection, and merely out of loneliness or boredom, important though such motivations are. We aim rather at satisfying a deeper need, which can be described in terms of an elementary desire for "belongingness". This is the goal, usually conceived in terms of group membership, for which sociability is the means, and which utopian "hope" chiefly aims at. It can be described as the antidote to that alienation so often associated with the moderns, and which was at the core of the problematic the young Marx grappled with. But much of the rest of modern sociology, philosophy and political theory bears out the point. To the sociologists Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner, the "modern mind" has been described as typically a "homeless mind", a condition "psychologically hard to bear" which induces a "permanent identity crisis".[12] Buried under the blizzard of impulses modern urban life creates, moving frequently and thus often uprooted, isolated, driven apart by the dominant ethos of individualism and competition, we feel we have lost both a unity with our community and a wholeness in our inner selves. Longing to retrieve both, we search accordingly for symbolic places where we imagine we once possessed such unity. Here a Heimat - the German term evokes a richness and depth of feeling lacking in English - or "home", now lost to some other group, or just to time, easily becomes the focus of imaginary virtues, peace and fulfilment.[13] This can be projected backwards or forwards, as well as to distant locations or even outer space. Where homesickness or Heimweh lacks a definitive, objective past or place upon which to focus, it may be preferable to conceive our imaginary home as a future utopia, where Heimatslosigkeit, the feeling of loss, is conquered. If such a word existed, "homefulness" would define this domain. Another German term, Zusammengehörigkeitsgefühl, does part of the work of giving a sense of "togetherness" as well as belonging. "Belongingness" will do as well in English, and is a rich and somewhat open-ended concept which clearly invites greater scrutiny than is possible here. It enjoys a prominent position in modern group psychology, which is a key entry to point to the study of utopianism.[14] As elemental as "our need for water", Kelly-Ann Allen writes, it is so fundamental that its manifestations often passed unnoticed.[15] Some see the need to belong as the primordial source for our desire for power, intimacy, approval, and much else. It commences in infancy, drives our willingness to conform through life, and may haunt us in our dotage. It is reflected in an attachment to places as well as people, and extends by association to all our senses, including smell and taste. The sense of belonging or connectedness is a crucial component in solidarity, and is sometimes even portrayed as the basis of morality as such.[16] Everyone has experienced the anxiety of feeling alone, abandoned, ignored, friendless, rejected, shunned, dispossessed, displaced, foreign, alien, and alienated. Not being part of a group we aspire to join can be devastating. Exclusion cuts us to the bone. Not feeling part of a place also makes us uncomfortable and unwanted. By the effort to exclude others from the in-group, or "othering", belongingness can thus also play a fundamental role in the dystopian imagination.[17] So the aspiration for friendship, association, the feeling of neighbourliness, in a word belongingness, guides much of our behaviour through life. The condition of homelessness can inspire imaginary future ideal societies, and in utopian literary form has often done so during the past two centuries or so. But it also still often induces backward-looking perspectives. It "has therefore engendered its own nostalgias - nostalgias, that is, for a condition of 'being at home' in society, with oneself and, ultimately, in the universe".[18] This endangers more accurate and balanced accounts by encouraging a nostalgic rewriting of history, where we hearken back to an imagined superior past, and redact unpleasant facts which interfere with this vision. This process corresponds to an unfortunate desire, of which we have been reminded far too often in the past few years, to want to be told things which please us rather than those whose truths make us feel uncomfortable, and which we would rather ignore or forget. We are happy to be lied to if the lie makes us feel better, and rationalist conceptions of the inevitable conquest of error by truth are thus misguided where they fail to acknowledge this weakness. This process is aided by the fact that memory is often faulty and selective, and we can concoct an ideal starting-point without worrying about its accuracy. The further back we go, too, the poorer are the records which might contradict us. This makes propaganda the more readily successful. This has a bearing on one ideology more than any other. Nationalism in particular often depends heavily on and can indeed be defined as an "imagined community", in Benedict Anderson's well-known phrase, which makes it a distinctive form of utopian group.[19] It often adverts to periods when our nation was "great" and its enemies vanquished and subservient, and frequently demands a rewriting of history to accord with such narratives, as modern debates over imperialism and the statues of heroic conquerors and defenders of slavery make abundantly clear. To those not motivated by the search for more balanced stories, but who primarily seek ego reinforcement amidst their national identity crises, the glorious fictional history of the imagined nation is often preferable over its more likely inglorious and bloodstained real past. Whole nations feel a romantic nostalgia, "a painful yearning to return home", for their lost golden ages of innocence, virtue and equality, and for their mythical places of origin, or the peak of their global power and influence.[20] Denying the reality of the present and compensatory displacement are key here. But the same process occurs as nations age, become more urban and complex, and are more driven by capitalist competition, by consumerism and the anxiety to work ever harder. Personal relations suffer under all these forces. Increasingly, suggests Juliet B. Schor, we "yearn for what we see as a simpler time, when people cared less about money and more about each other".[21] Susan Stewart sees such nostalgia as a "social disease" which seeks "an authenticity of being" through presenting a new narrative, while denying the present.[22] We can readily see, then, that all major political ideologies advert to one or another glorious pasts or future images which recall or herald greater individual fulfilment, prosperity, and more powerful bonds of community. Not all address belongingness in the same manner, however. Liberalism tends from the early nineteenth century onwards to stress the value of individuality, and often under-theorises the need for and benefits of sociability.[23] Communitarian liberalism has made some effort to redress this omission, with varying degrees of success. Older forms of conservatism tended to locate the ideal state in the past and in more traditional systems of ranks, though this is not the case for more recent incarnations. Socialism is closest both semantically and programmatically to More's original utopian paradigm, and places great stress on the effort to rebuild communities around various artificially-constructed ideas of sociability and solidarity. To that inveterate critic of utopian aspiration, Leszek Kolakowski, Marxism-Leninism in particular shared a desire with all utopians "to institutionalize fraternity", adding that "an institutionally guaranteed friendship … is the surest way to totalitarian despotism", since a "conflictless order" can only exist "by applying totalitarian coercion".[24] To summarise the argument briefly presented here. What we can for short call the "3-2-1" definition of utopianism involves seeing the subject as possessing three faces or dimensions, utopian social theory, literary utopias and dystopias, and utopian practice; two functions, that of providing a space of psychological alterity, and that of permitting the futurological dream of ideal societies; and one content, defined by belongingness. Utopianism is a stand-alone ideology insofar as it adopts variants on the Morean paradigm, but all major systems of ideas have utopian or ideal components which are used as reference points to suggest the goals of their systems. All forms of utopianism aim in particular at providing circumstances in which belongingness can be fulfilled. This ideal can be understood as the resolution of the central problem of alienation in modern life, an issue crucial to Marxism but equally to many other strands of modern social theory. The chief task now before us in the 2020s, to determine how it can achieve practical form in the face of the looming environmental catastrophe of the present century, can be addressed at another time. [1] Lyman Tower Sargent. Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 5. This typology dates from 1975, and is revised in Sargent's "The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited", Utopian Studies, 5 (1994), 1-37. See further Sargent's "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [2] Krishan Kumar. Utopianism (Open University Press, 1991). [3] On the aversion to adopting the utopian label, see David Estlund. Utopophobia. On the Limits (If Any) of Political Philosophy (Princeton University Press, 2020). Estlund argues that "a social proposal has the vice of being utopian if, roughly, there is no evident basis for believing that efforts to stably achieve it would have any significant tendency to succeed" (p. 11). [4] See my Mill and Paternalism (Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 123-72. [5] This typology is defended in my (and Christine Lattek) "Radicalism, Republicanism, and Revolutionism: From the Principles of '89 to Modern Terrorism", in Gareth Stedman Jones and Gregory Claeys, eds., The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 200-254. [6] See Lyman Tower Sargent. "Ideology and Utopia", in Michael Freeden, Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 439-51. [7] I draw here on my After Consumerism: Utopianism for a Dying Planet (Princeton University Press, forthcoming). [8] This leaves aside the broader problem as to how far any ideal society rests on the labour or exploitation of some group(s), for whom the utopia of one group may thus become the dystopia of another. Decolonising utopia is an ongoing project. Some communes, like that founded by Josiah Warren in Ohio, have been called "Utopia". [9] See Martin Buber. Paths in Utopia, and Ernst Bloch. The Principle of Hope (3 vols, Basil Blackwell, 1986). Ludwig Feuerbach's idea of God as a projection of human desire, and of love as the essence of Christianity, formed the methodological starting-point for Marx's theory of alienation in the "Paris Manuscripts" of 1844. [10] Ruth Levitas. The Concept of Utopia (Syracuse University Press, 1990), p. 181. See also Fredric Jameson. Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (Verso, 2005). [11] An earlier version of this argument is offered in "News from Somewhere: Enhanced Sociability and the Composite Definition of Utopia and Dystopia", History, 98 (2013), 145-173. [12] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind. Modernization and Consciousness (Pelican Books, 1974), p. 74. [13] Its opposite is Heimatslosigkeit, which has no exact English equivalent, since "homefulness", sadly, is not a word and "homelessness" simply means being forced through poverty to live outside of a dwelling. Hence the use here of belongingness, despite its awkwardness. [14] It is acknowledged as such, however, chiefly in the literature on communitarianism. [15] Kelly-Ann Allen. The Psychology of Belongingness (Routledge, 2021), p. 1. [16] B. F. Skinner insists that "A person does not act for the good of others because of a feeling of belongingness or refuse to act because of feelings of alienation. His behaviour depends upon the control exerted by the social environment" (Beyond Freedom and Dignity, Penguin Books, 1973, p. 110). [17] See my Dystopia: A Natural History (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 34-6. [18] Peter L. Berger, Brigitte Berger and Hansfried Kellner. The Homeless Mind, p. 77. [19] Benedict Anderson. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 1991). [20] Fred Davis. Yearning for Yesterday. A Sociology of Nostalgia (The Free Press, 1979), p. 1. [21] Juliet B. Schor. The Overspent American. Upscaling, Downshifting, and the New Consumer (Basic Books, 1998), p. 24. [22] Susan Stewart. On Longing (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), p. 23. [23] For a survey of this problem vis-à-vis John Stuart Mill, for instance, see my John Stuart Mill. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). [24] Leszek Kolakowski. Modernity on Endless Trial (University of Chicago Press, 1990), pp. 139, 143. The argument here turns largely on two assumptions, firstly that "human needs have no boundaries we could delineate; consequently, total satisfaction is incompatible with the variety and indefiniteness of human needs" (p. 138), and secondly opposition to "The utopian dogma stating that the evil in us has resulted from defective social institutions and will vanish with them is indeed not only puerile but dangerous; it amounts to the hope, just mentioned, for an institutionally guaranteed friendship". by Aristotle Kallis

For centuries ‘civilisation’ has been a loaded, unstable, and ambiguous term. It has been used as a description of the present but also as an aspirational projection of a process that promises to lead to perfection. It could be seen to designate a positive process and trajectory, as well as a desired destination in the future; or conversely it could be suggestive of liberation from the ghosts of a supposedly primitive and barbaric prior human state. At times claimed to be objective or subjective, absolute or relative, universal or culture-specific, permanent or temporary and reversible, ‘civilisation’ has proved to be a formidable discursive formation that thrives in controversial polysemy.