|

6/12/2021 There is always someone more populist than you: Insights and reflections on a new method for measuring populism with supervised machine learningRead Now by Jessica Di Cocco

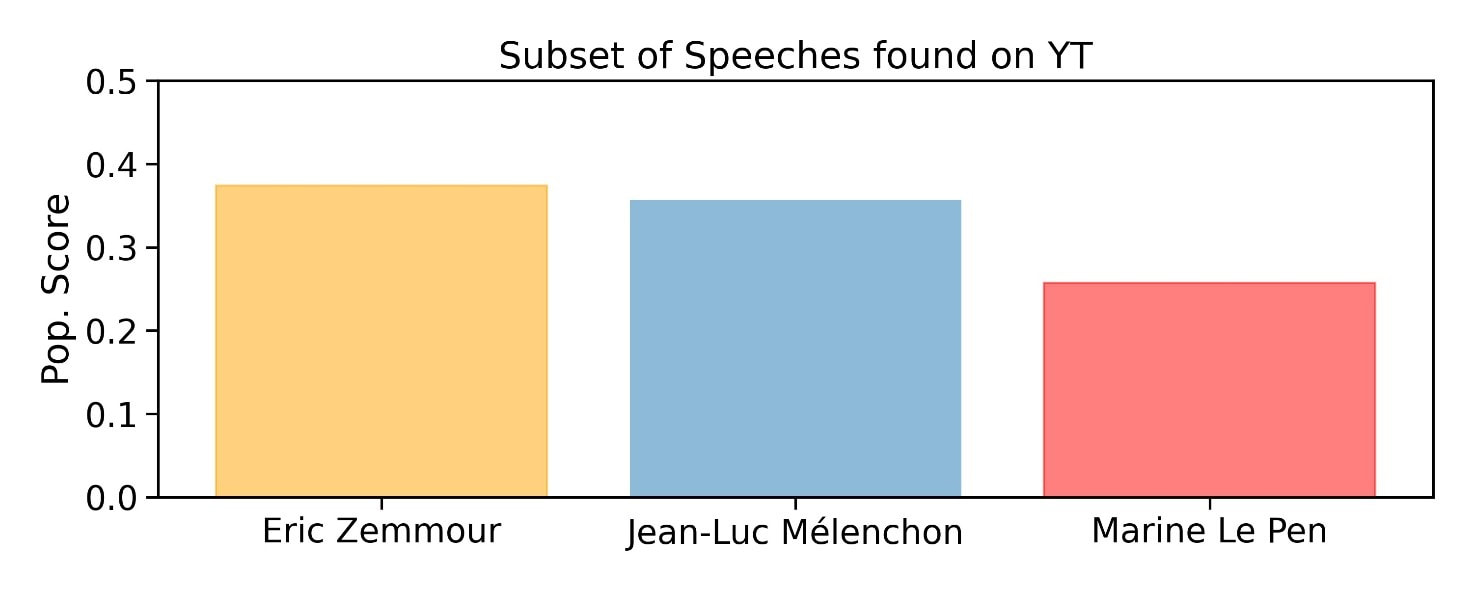

The debate on populism and its effects on society has been the subject of numerous studies in the social and non-social sciences. The interest in this topic has led an increasing number of scholars to analyse it from different perspectives, trying to grasp its facets and consider the national contexts in which populist phenomena have developed. The scholarly literature has increasingly highlighted the need to adopt empirical approaches to the study of populism, both looking at the supply side (i.e., how much populism political actors ‘offer’) and at the demand side (i.e., how much populism citizens and potential voters ‘demand’).[1] The transition from almost exclusively theoretical to quantitative studies on populism has been accompanied by several issues of no small importance concerning, for instance, problems of a statistical nature or related to data availability. From the point of view of the demand for populism, studies have shown that its determinants are numerous and often interconnected—ranging, for instance, from social status[2] to institutional trust,[3] from the deterioration of objective well-being[4] to perceptions of subjective well-being.[5] Analyses aimed at studying the causes and effects of populism generally come up against the statistical issues we mentioned earlier. Scientists familiar with empirical analyses might be aware of the problems of endogeneity, reverse causality, and omitted variables that can affect the reading of the final results. For example, the literature has often focused on the links between populism and crisis. However, the direction of what influences what (and, therefore, the causal relationship between them) remains controversial. As Benjamin Moffit has highlighted, rather than just thinking about the crisis as a trigger of populism, we should also consider how populism attempts to trigger the crisis. Populist actors participate in the ‘spectacularisation’ of failure underpinning crisis. Therefore, crises are not purely external to populism; they are internal key elements.[6] Another example concerns reverse causality. There is general agreement that economic conditions impact people’s voting choices. Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether facts or perceptions of these conditions impact more on voting choices. Larry Bartels has argued that it is not the actual economic conditions that matter, but rather that it is how this is interpreted by political parties that shapes perceptions.[7] Hence, there could be reverse causality at play, in which populist parties might impact wider perceptions of economic conditions.[8] From a populist supply perspective, studies have long focused on the classifications that scholars in the field have periodically drawn up.[9] Other scholars have gradually adopted alternative methods, such as focusing on the textual analysis of programmes, speeches, and other textual sources of leaders and parties. Our work is situated within this field of research on populism and, more generally, on ‘populisms’. We use the plural because we refer to different forms of populism that can develop along the entire ideological continuum and in very diverse national contexts. The diversity in the forms of populism has called for a deeper reflection on how we can compare them across the countries and measure them to consider the possible intensities and nuances. Measuring populism Indeed, one of the main challenges in comparative studies on populism is how to measure it across a large number of cases, including several countries and parties within countries. We address this issue in our recent work, in which we use supervised machine learning to evaluate the degrees of populism in evidence in party manifestos.[10] Previous literature had already explored the possibility of using different methods, including textual analysis,[11] [12] and machine learning has cleared the way for further research in this direction. What are the advantages of using automated text-as-data approaches for investigating diversified political questions, populism, and others? For example, these techniques allow for the analysis of large quantities of data with fewer resources, inferring actors’ positions directly from the texts, and obtaining more replicable results. Furthermore, they make it possible to focus on elites and their ideas,[13] and thereby obtain continuous populism measures which, unlike dichotomous ones, better account for the multi-dimensionality of populism and differentiate between its degrees.[14] Finally, automated textual approaches can help capture the rapid changes and transformations of the party landscape. We used automated textual analysis to derive a score which acts as a proxy for parties’ levels of populism. We validated the score using different expert surveys to check its robustness and verify the most correlated dimensions based on the literature on populism. We obtained a score that we can use to measure parties' levels of populism per year and across countries. In an ongoing study, we have applied the score for testing the Populist Zeitgeist hypothesis. According to Cas Mudde,[15] a populist Zeitgeist is spreading in Western Europe, which means that non-populist parties are becoming increasingly populist in their rhetoric in response to populists’ increasing success. We found that the entrance of populist contents into the debate within non-populist parties seems to be an Italian peculiarity. Prompted by this finding, we started investigating the possible issues connected with this specific trend and concluded that Italy has exhibited sharper decreases in crucial socio-economic dimensions, such as satisfaction with democracy, trust towards institutions, and objective and subjective well-being. For this exploratory analysis, we used data from European Social Survey[16] over the last two decades. The French case We can use the same method to investigate other textual sources and answer different questions within the field of populism analysis. For this purpose, we have collected a small corpus composed of 300 sentences drawn from TV interviews and debates available on YouTube and involving some of the candidates for the French Presidential Election that is due to take place in April 2022. The field of candidates is currently still somewhat unclear, since Eric Zemmour, an outsider leaning towards the far right who has enjoyed a degree of insurgent popularity in recent opinion polling, has not yet formally announced his candidacy. Given the limited availability of data, at the moment, we only focused on Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Marine Le Pen, and Eric Zemmour. Even if the corpus needs further improvement, we can already offer a number of interesting insights for more profound reflections and future studies. For those unfamiliar with French politics, the three leaders we chose for analysis exhibit radical and (or) populist traits. However, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen are already well-known to the general public, the third figure mentioned, Eric Zemmour, is new to the political scene. He has gained prominence chiefly as a controversial writer and columnist, politically positioned to the right of Marine Le Pen. Zemmour’s positions are so radical that they have succeeded in overtaking those of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National on the right, ranging from the theory of ‘ethnic replacement’ and anti-abortionism to the repeal of gay rights and nostalgia for the ‘golden age’ of French colonialism. Convicted several times for inciting racial hatred, he has recently be in court for his remarks on unaccompanied migrant minors. For this trial, he is accused of “complicity in provoking racial hatred” and “racial insult”. Interestingly, by comparison, when listening to Marine Le Pen speaking, she might appear almost moderate, if not progressive, even though she is a notoriously radical right-wing populist. Is this just a feeling, or is this the case? Undoubtedly, Zemmour’s racist and sexist statements would put many extreme right-wingers to shame, and he himself has described Le Pen as a ‘left-wing’ politician. At the same time, the familiar theories of electoral competition also teach us that the electoral arena is made up of spaces in which parties and their demands are located. On that basis, it cannot be ruled out that in the presence of such an ‘extreme’ candidate, Marine Le Pen may opt for (or find herself choosing) more moderate or progressive positions, while still maintaining her attachment to her ideology’s cardinal elements, such as anti-immigration arguments, anti-Islam positions, economic nationalism, and anti-establishment claims. In all of this, the figure of radical left-wing leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon stands out; at the time of writing this article, he is the only leader who has accepted a televised confrontation with Zemmour. Some interesting reflections also arise on how the extreme right and left can share aspects as for what they offer to their potential electorate, especially if the games are played out on populist terrain. To perform the analysis, we derived the scores by applying the methodology we proposed in our work. The algorithm that we use is capable of discriminating between sentences belonging to populist or non-populist parties of a given country. The final party score that we obtained is the fraction of sentences that the classifier considers as being more likely to belong to prototypically populist partisan speech in France. Therefore, the score measures the probability that a sentence is drawn from an speech of a prototypical French populist party. According to our analysis, Zemmour is the most populist leader, with Mélenchon close behind and Marine Le Pen increasingly isolated in the rankings (see Fig. 1 below). And Macron? What of the other candidates? At the time of writing, Macron has not yet officially launched his election campaign, limiting himself to giving speeches and interviews in his capacity as head of government rather than as a future presidential candidate. As for the other candidates, firstly they belong to more ideologically moderate parties; secondly, they are starting to give their first interviews at the time of writing. The association between moderate stances and anti-populism on the one hand, and extremism and populism on the other, is not new in the literature on populism to the extent that the terms ‘populist’ and ‘radical’ have been almost used interchangeably.[17] On the contrary, moderate parties tend to be anti-populist by nature, since they do not exhibit the traits that are typically attributed to populist actors (for example, anti-elitism, people-centrism, the Manichean worldview).[18] Although many French moderate parties have launched their electoral campaign, they are far from generating the same levels of public outcry as the three populists mentioned above. A clamour that seems to confirm the old saying that, as Oscar Wilde puts it, ‘there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about’. Even if it means finding out that there is always someone more populist than you. Conclusion For this article, we have limited ourselves to showing how our method based on supervised machine learning has allowed us to obtain quick and valuable results to start new analyses and reflections. However, we shall have to wait a little longer to build a complete and comprehensive corpus, and to validate our results with further speeches as they take place and enter French political discourse. There are many questions that deserve to be investigated in the coming months. How will the French electoral campaign evolve? Will the levels of populism increase as the presidential elections approach? Does our method allow us to distinguish between left- and right-wing populisms? Is it possible to calculate the distance (or proximity) between the various leaders’ substantive rhetoric? These are just some of the questions to ask ourselves as time goes on. We will try to provide some answers in the coming weeks and months, expanding our analysis to include new leaders, first and foremost the current President Macron, new speeches, and new validations. For now, it remains to be seen how far the populist clamour convinces others to shift in their direction. [1] Meijers, Maurits J., and Andrej Zaslove. "Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach." Comparative political studies 54.2 (2021): 372-407. [2] Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. "Populism as a problem of social integration." Comparative Political Studies 53.7 (2020): 1027-1059. [3] Algan, Yann, et al. "The European trust crisis and the rise of populism." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017.2 (2017): 309-400. [4] Guriev, Sergei. "Economic drivers of populism." AEA Papers and Proceedings. Vol. 108. 2018. [5] Guiso, Luigi, et al. Demand and supply of populism. London, UK: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2017. [6] Moffitt, Benjamin. "How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism." Government and Opposition 50.2 (2015): 189-217. [7] Bartels, Larry M. "Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions." Political behavior 24.2 (2002): 117-150. [8] van Leeuwen, Eveline S., and Solmaria Halleck Vega. "Voting and the rise of populism: Spatial perspectives and applications across Europe." Regional Science Policy & Practice 13.2 (2021): 209-219. [9] Van Kessel, Stijn. Populist parties in Europe: Agents of discontent?. Springer, 2015. [10] Di Cocco, Jessica, and Bernardo Monechi. "How Populist are Parties? Measuring Degrees of Populism in Party Manifestos Using Supervised Machine Learning." Political Analysis (2021): 1-17. [11] Jagers, Jan, and Stefaan Walgrave. "Populism as political communication style." European journal of political research 46.3 (2007): 319-345. [12] Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels. "Measuring populism: Comparing two methods of content analysis." West European Politics 34.6 (2011): 1272-1283. [13] Hawkins, Kirk A., et al. "Measuring populist discourse: The global populism database." EPSA Annual Conference in Belfast, UK, June. 2019. [14] Zaslove, A. S., and M. Meijers. "Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach." (2020). [15] Mudde, Cas. "The populist zeitgeist." Government and opposition 39.4 (2004): 541-563. [16] https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ [17] EUROPE, POPULIST RADICAL RIGHT PARTIES IN, and C. Mudde. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge university press, 2007. [18] Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. "The ideational approach to populism." Latin American Research Review 52.4 (2017): 513-528. Fig. 1: The ranking of the leaders based on their TV speeches and debates. The corpus is a sample of speeches, further sentences will be added to expand the analysis to other leaders and validate the results.

Comments are closed.

|

Details

Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed