by Joanne Paul

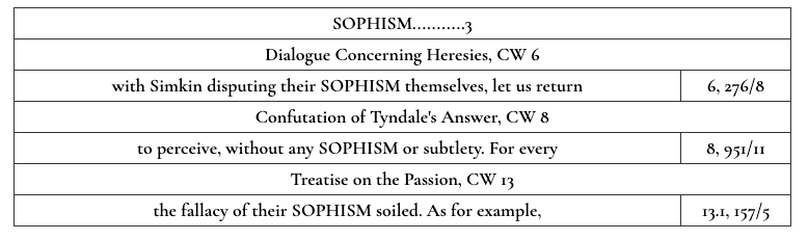

A lot can be said about the relationship between utopianism and ideology, and Gregory Claeys covered much of it in his comprehensive and detailed contribution to this blog.[1] As with all discussions of utopianism, however, participants cannot help but acknowledge the roots of the concept in the originator of the term, Thomas More’s masterfully enigmatic Utopia (full title: On the Best State of the Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia). Whether it was More himself who coined the term (it has been suggested it was in fact Erasmus), and acknowledging the longer (and global) history of imagined ideal states, any consideration of utopianism must at some point trace itself to More’s sixteenth-century text. This can make for some awkward anachronistic connections, especially for anyone concerned particularly with the importance of contextualism in the analysis of historic texts (as I am). Even the question of whether there is an ‘ideology’ present in More’s text can immediately be countered with the charge of anachronism. This is, of course, an issue with the term itself. However, much like we might acknowledge utopias (or utopian thinking) prior to 1516, we might also entertain the suggestion that ideology as a concept (if not a term) might have existed prior to the Enlightenment, and that various contemporary ideologies might also have their roots in the Renaissance, even if More would have been perplexed—but likely intrigued—by the term itself. The purpose of this piece, then, is to explore two interrelated questions. First, whether we can think about ideology and Utopia without giving ourselves entirely over to anachronism and thus a reading of the text that cannot be substantiated. Second, in a similar vein, to test the waters with a variety of ‘ideologies’ with which Utopia has been associated: republicanism, liberalism, totalitarianism/authoritarianism, socialism/communism, and, of course, utopianism. In this ‘testing’, the first criteria will be consistency within the text itself, but in establishing this, I will be reading the text in the context of More’s times and other works. Utopia is too frequently read as a stand-alone text despite—or perhaps because of—More’s substantial oeuvre. It is an intentionally ambiguous work, which is why so many different and even opposed ideologies can be read into it. In order to test the legitimacy of these readings, we must understanding Utopia in the context of More’s work more widely. A short caveat: none of this, of course, precludes the use of Utopia as an inspiration or foundation for a variety of ideological arguments, and Claeys has repeatedly made an impassioned and vitally important argument for the role of utopian thinking in meeting the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century (along with another contribution to this blog by Mathias Thaler)[2]. Political theorists and philosophers have—often very good—reasons for playing harder and faster with the ‘rules’ of historical contextualism (for more on this, see in particular the work of Adrian Blau).[3] There are, however, also good reasons to want to be attentive to the particularities of an utterance in its historical context, which I will not rehearse here, but which I hope are evident in what follows. Ideology and Utopia Does the idea of ‘ideology’ fit with a sixteenth-century intellectual mindset? More was not unfamiliar with the notion of ‘-isms’, often seen as the shorthand for identifying ideologies (though not in the explicitly modern sense).[4] Most of these ‘-isms’ were religious, not just less ‘ideological’ words like baptism, but those that more accurately fit the definition of a ‘system of beliefs’ such as ‘Judaism’, which More used in his Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer (1532).[5] It was the Reformation, Harro Höpfl has noted, which saw the widespread use of ‘isms’ to refer to ‘theological or religious positions considered heretical, and also to refer to the doctrines of various philosophical schools’.[6] Indeed More used the term ‘sophism’ (see the excerpt from the concordance above) in a way that arguably had ideological connotations, and not expressly or necessarily religious ones.[7] That being said, Ideology’s association with political ideas as wholly distinct from religious ones might have not squared with More’s worldview. Any religion can fit the definition of an ‘ideology’ and religious ideas permeated every aspect of More’s world, including—and especially—politics. The way in which Utopia can and has been read as an especially secular text is part of what makes it an enduringly popular text to study, certainly more than More’s other—obviously (and vehemently) religious—writings. There is something attractively secular about More’s pre-Christian island, which is based more obviously on classical pagan influences than medieval Christian ones. For this reason, it is temptingly easy to read a series of ideologies into this short book. The interesting question for a historian like myself becomes whether these were ideas available and attractive to More himself. Republicanism The island of Utopia is obviously and expressly a republic, and the neo-classical humanist More would have fully understood what this entailed. Both books of the text articulate, as Quentin Skinner has demonstrated, arguments for a Ciceronian vita activa, on which republicanism is based.[8] Although each Utopian city is ruled by a princeps, they are elected, and rule in consultation with an assembly of elected ‘tranibors’. The island as a whole is ruled by a General Council, made up of representatives elected from each city. This description of Utopia is framed by a discussion about the merits of the active life in the context of a monarchy, echoing similar discussions in Isocrates, Cicero, Erasmus, and others.[9] Does this align Utopia with ‘republicanism’ as an ideology? Certainly, the text deserves an important place in the development of that ideology from its ‘Athenian and Roman roots’, especially when read in the context of More’s other writings, which express a conciliarism that clearly has overlaps with classical republicanism. In his Latin Historia Richardi Tertii, More writes that parliament, which he calls a senatus, has ‘supreme and absolute’ authority, and in his religious polemics, he is keen to draw a connection between the parliament and the General Council.[10] The latter, he writes, has the power to depose the Pope and, whereas the Pope’s primacy can be held in doubt, ‘the general councils assembled lawfully… the authority thereof ought to be taken for undoubtable’.[11] Both parliament and the General Council are authorised representatives of the whole community, whether the church or the realm.[12] More also expresses ideas in line with what has come to be known as ‘republican liberty’: ‘non-domination’ or ‘that freedom within civil associations’, impling the lack of an ‘arbitrary power’ which would reduce ‘the status of free-man to that of slaves’.[13] In his justification of the importance of law, More writes, that ‘if you take away the laws and leave everything free to the magistrates… they will rule by the leading of their own nature… and then the people will be in no way freer, but, by reason of a condition of servitude, worse’.[14] This aligns with the Renaissance view of tyranny as ruling according to one’s own willful passions, rather than right reason. More certainly saw unfreedom in the rule of licentia (or license) over reason.[15] This could be found both in the rule of a single tyrant and in the anarchy of pluralism, a situation he feared would arise from Lutheranism.[16] As such, a firmly established structure of self-government, like that in Utopia, was the ideal way to ensure his notion of freedom, one that was largely in accordance with the republican tradition. Liberalism This is in contrast with notion of freedom advanced in Utopia by the character Raphael Hythloday, which we might think of as more in line with a ‘liberal’ perspective. He does not want to ‘enslave’ himself to a king and prefers to ‘live as I please’, certainly more ‘license’ than ‘liberty’ in More’s perspective.[17] There is an inherent contradiction between republican and liberal notions of liberty. In so far as More can be said to express something of the former, he is deeply against the latter. Individualism sits at the heart of liberalism; it is, as Michael Freeden and Marc Stears have suggested (though not without qualification), ‘an individualist creed’, seeking to enshrine ‘individual rights, social equality, and constraints on the interventions of social and political power’.[18] Liberalism was a product of the Enlightenment, and so More could not properly be said to be its opponent, but he did powerfully critique what we might see as its nascent constitute parts. In his other works, More often repeats a distinction between the people (populus) and ‘anyone whatever’ (quislibet), to the derision of the authority of the latter.[19] This lies at the heart of his fear of anarchy and Lutheranism, which he accuses of transferring ‘the authority of judging doctrines… from the people and deliver[ing] it to anyone whatever’.[20] In Utopia, we can see this critique of proto-individualism in his central message about pride, which he (with Augustine) takes to be the root of all sin, as it necessarily cuts across the bonds that should unite the populus. Pride is not just self-love, but self-elevation, a form of comparative arrogance that seeks to mark one out from others (a sin he associates with the scholastics, vice-ridden nobility, Lutherans, and indeed most of his opponents). Utopia has thus been read as a repressive regime which quashes—rather than upholds—freedom. This is from the perspective of post-Enlightenment liberalism, and takes Utopia perhaps more literally than it is meant. Read as a critique of the pride which we might associate with a sort of proto-individualism, it offers a powerful critique of an ideology which is—it must be acknowledged—in need of a reassessment. Totalitarianism/Authoritarianism It is for its anti-liberal qualities that Utopia has ended up associated with some of the darkest ideologies of the 20th century. More’s biographer, Richard Marius, called his views about education—certainly present in Utopia—‘an authoritarian concept, suitable for an authoritarian age’. Others have associated Utopia explicitly with totalitarianism.[21] Of the two, authoritarianism might be the more likely. There is a very clear desire in the setting out of the Utopian political and social system to have laws inculcated. The emphasis on what is referred to as ‘education’ or ‘training’ [institutis] might make 21st century readers think instead of socialisation or, more pessimistically, indoctrination. Priests, for example, are responsible for children’s education, and must ‘take the greatest pains from the very first to instil into children’s minds, while still tender and pliable, good opinions which are also useful for the preservation of the commonwealth.’[22] For this, not only are laws and institutions employed, but also public opinion. In a land where everything is public, nothing is private, and thus all is subject to public opinion: ‘being under the eyes of all, people are bound either to be performing the usual labor or to be enjoying their leisure in a fashion not without decency’.[23] This ‘universal behaviour’ is the secret to Utopia’s success. What I think More wanted to draw attention to in Utopia is the way in which this happens anyway, and to reorient the inculcation of values (or ‘opinions’) towards ‘truer’ or more ‘eternal’ (of course even ‘divine’) values. Utopians laugh at gems and precious metals because they associate them with fools and chamber pots. We value them because we associate them with the wealthy and powerful. The Utopians are ‘made’ to be dutiful citizens. As Book One suggests, ‘When you allow your youths to be badly brought up and their characters, even from early years, to become more and more corrupt, to be punished, of course, when, as grown-up men, they commit the crimes from boyhood they have shown every prospect of committing, what else, I ask, do you do but first create thieves and then become the very agents of their punishment?’.[24] In both cases, More suggests in Utopia and elsewhere, these values (or opinions) are built on a sort of ‘consensus’. The suggestion that this is authoritarian stems from a post-Enlightenment perspective that looks to see the liberal individual protected (as set out in part III above), of which More is many ways presenting a sort of ‘proto-critique’. While the republicanism of Utopia would, to some minds (and I would suspect to More’s), prevent it from being accurately labelled authoritarian—the citizenry is, after all, involved in its governance—to others this would not suffice. Would More have minded an ‘authoritarian’ society, if the values it inculcated with the ‘right’ ones? Perhaps not. More’s point, however, that we all submit to and are shaped by various sources of authority, and that the power to reorient the values cultivated by these authorities has been and continues to be a powerful one. Socialism/communism The early socialist thinkers were inspired by More to think that they might make people better through their organisation of society and its institutions (primarily education). In this historical context, we also have to contend, at least for a moment, with utilitarianism, and the Utopian’s ‘hedonism’ (or more properly Epicureanism). Jeremy Bentham, of course, held stock in the factory of utopian socialist Robert Owen. Helen Taylor (stepdaughter of J.S. Mill) wrote that in Utopia More ‘lays down a completely Utilitarian system of ethics’ as well as an ‘eloquently and yet closely reasoned defense of Socialism’. More was not an Epicurean (nor, of course, a utilitarian), though was interested to get back to more ‘real’ or ‘true’ pleasures over those false ones (we might think again of Utopians’ views of gems and precious metals). What I have called his republicanism might have also meant he was more interested in the good of the many over the few, though perhaps not quite in those terms (instead, the common good over any individual good). This emphasis on ‘common good’, of course, translates into ‘common goods’ in Utopia, where everything is held in common. This abolition of anything private (and thus private property) has led him to be read as a socialist and/or communist thinker, the latter not least by Marx and Engels. Beyond Utopia, however, More does make some very un-socialist comments. Through the central figure of Anthony in his Dialogue of Comfort (1534), More suggests in an Aristotelian vein that economic inequality is essential for the commonwealth; there must be ‘men of substance… for else more beggars shall you have’.[25] The golden hen must not be cut up for the few riches one might find inside. The larger point More wants to make in this text, however, is that even the richest do not ‘own’ their property. Property is a fiction and needs to be seen as such. Thus a rich man can keep his wealth so long as he recognises it is only his by the fictions of the society in which he lives, and ought (therefore) to be used to benefit the commonwealth. Wealth, position, and so on, More advocates, ‘by the good use thereof, to make them matter of our merit with God’s help in the life after.’ This is not a socialist nor a communist position, and it is certainly not materialist. More’s entire argument seeks to cultivate a conscious neglect of material realities in favour of the decidedly immaterial. Utopia, then, serves as a reminder of the immaterial realities underneath the social fictions generated in Europe (property, money, social hierarchy, etc). Living in that—shall we say—‘fictive reality’, however, means using those falsities towards the higher ends. As More’s friend John Colet put it: ‘use well temporal things. Desire eternal things.’ Utopianism Utopianism is at once an ideology, has characteristics similar to ideology, might encompass all ideologies, and is entirely opposed to it.[26] I will not rehearse the arguments of Sargent and Claeys here, but the three ‘faces’ that they speak of: utopian literature, utopian communities/practice, and utopian social theory are of course drawn from More’s 1516 text, and Sargent even suggests that ‘the meaning of [utopia] has not changed significantly from 1516 to the present’. So can we accept the obvious, then, that utopianism, as an ideology, is present in More’s text? Unfortunately, this question would seem to hinge on the fraught question of More’s sincerity in setting out the merits of the island of Utopia and the extent to which it is a community that he intended his readers to emulate. In many ways, our answer to this question has the power to overturn the very notion of any ideology being present in at least a surface reading of Utopia. If we were to conclude that Utopia is pure satire, and that the only arguments made in it are negative deconstructive ones, we would be hard-pressed to find any ideology within it at all.[27] I have made my own arguments about the central argument of Utopia, which I will not rehearse here, but the good news is that we can engage with the issue of utopianism in Utopia without answering this seemingly unanswerable question. Say what you will about the difficult question of More’s intentions, it would be difficult indeed to suggest that he was putting forward a blueprint of any kind for the construction of a practical community or endorsing the direct adoption of any of the practices exhibited in Utopia. The idea that Utopia exhibits—to use the words of Crane Brinton—‘a plan [that] must be developed and put into execution’ creates a sense of unease, to say the least. Afterall, More famously ends his text with the conclusion that ‘in the Utopian commonwealth there are very many features that in our own societies I would wish rather than expect to see’.[28] Despite the consensus that this passage is central to our understanding of Utopia, scholars have generally not attempted to read this statement in the context of More’s other works. When we do, we see that More applied this phrase elsewhere as well, and provided more of an explanation than he does in Utopia. In his Apology of 1533, More tells his reader that it would be wonderful if the world was filled with people who were ‘so good’ that there were no faults and no heresy needing punishment. Unfortunately, ‘this is more easy to wish, than likely to look for’.[29] Because of this reality, all one can do is ‘labour to make himself better’ and ‘charitably bear with others’ where he can. It is an internal reorganisation of priorities, drawn in large part from More’s reading of Augustine; what is common and shared must be prioritised over that which is one’s own. This, I have argued elsewhere, is what sits at the heart of More’s oeuvre, and we should be unsurprised to find it in Utopia as well. It is not the case, then, that More is advocating for what we might recognise as utopianism, but rather than Utopia is re-enforcing the arguments he makes elsewhere: the destructive power of pride and the personal need to prioritise the common over the individual. Conclusion: Moreanism? Does this mean, at last, we have come to an ideology in Utopia? A sort of republicanism-light, a proto-communitarianism, an anti-liberalism? I leave it to political theorists to hash out what More’s view might be termed—or indeed if a label is useful at all. Utopia can, indeed, be read in a variety of ways, which support a diversity of ideological positions. It becomes more difficult, I think, to read these positions into More’s thought as a whole. When we examine his corpus, we see a preoccupation with the common good, expressed through representative quasi-republican institutions, and the eternal/immaterial, but also a pragmatism (even ‘realism’?) about the artificialities of the world in which we live. It is the work of a much larger piece to flesh this out in whole, and this small article has instead focused largely on what More cannot be said to be. Hopefully, however, this is in itself a utopian exercise. In understanding Not-More, we might better understand More himself. [1] ‘Utopianism as a Political Ideology: An Attempt at Redefinition’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/04/utopianism-as-a-political-ideology-an-attempt-at-redefinition.html. [2] ‘“We Are Going to Have to Imagine Our Way out of This!”: Utopian Thinking and Acting in the Climate Emergency’, IDEOLOGY THEORY PRACTICE, accessed 8 February 2022, http://www.ideology-theory-practice.org/1/post/2021/09/we-are-going-to-have-to-imagine-our-way-out-of-this-utopian-thinking-and-acting-in-the-climate-emergency.html. [3] Adrian Blau, ‘Interpreting Texts’, in Methods in Analytical Political Theory, ed. Adrian Blau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 243–69, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316162576.013. [4] H. M. Höpfl, ‘Isms’, British Journal of Political Science 13, no. 1 (January 1983): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003112. [5] Thomas More, The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More: The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, ed. Louis A. Schuster, Richard C. Marius, and James P. Lusardi, vol. 8 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), 782. [6] Höpfl , ‘Isms’, 1; most of these do not appear in More’s work, though ‘papist’ does (24 times), which is a derivation of ‘papism’; likewise ‘donatists’ (26 times) from ‘donatism’ see https://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance/. Of course, this discussion is of English ‘isms’, and Utopia, along with a handful of More’s other writing, is Latin. Ism itself is a Latin (from Greek, and into French) derivation, for the suffix ‘-ismus’ (masculine). However, text-searches and concordances did not turn up many of these either, nor do ‘isms’ appear in the text of translations consulted. [7] ‘Concordances’, Thomas More Studies (blog), accessed 8 February 2022, http://thomasmorestudies.org/concordance-home/. [8] Quentin Skinner, ‘Thomas More’s Utopia and the Virtue of True Nobility’, in Visions of Politics: Volume 2: Renaissance Virtues (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 213–44. [9] Joanne Paul, Counsel and Command in Early Modern English Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), chapter 1. [10] More, Letters, 321. In the Confutation, 287 he justifies this approach, suggesting that ‘senatus Londinensis’ could be translated ‘as mayor, aldermen, and common council’. [11] More, Letters, 213. [12] More, Confutation, 146, 937. [13] Quentin Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), ix-x. This is not inconsistent with the fact that free-men could indeed become slaves in Utopia. In fact, the presence of slaves only highlights the emphasis on the sort of freedom enjoyed by law-abiding Utopian citizens.[13] Slaves are drawn from either within Utopia - those condemned of ‘some heinous offence’ - or without – captured prisoners of war, those who have been condemned to death in their own country or, thirdly, those who volunteer for it as a preferable option to poverty elsewhere.[13] Notably, in none of these cases is slavery hereditary and slaves cannot be purchased from abroad; Thomas More, More: Utopia, ed. George M. Logan and Robert M. Adams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 77. [14] More, Responsio Ad Lutherum, 277. All references to More’s works taken from the Yale Collected Works series, unless otherwise indicated. [15] Skinner, Hobbes and Republican Liberty, 30-1. [16] Joanne Paul, Thomas More (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 98-9. [17] More, Utopia, 13. [18] Michael Freeden and Marc Stears, ‘Liberalism’, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [19] Paul, Thomas More, 99. [20] More, Responsio, 613. [21] Richard Marius, Thomas More: a biography (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 199), p. 235; Wolfgang E. H. Rudat, ‘Thomas More and Hythloday: Some Speculations on Utopia’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 43, no. 1 (1981): 123–27; J. C. Davis, Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Hanan Yoran, Between Utopia and Dystopia: Erasmus, Thomas More, and the Humanist Republic of Letters (Lexington Books, 2010), 13, 167, 174, 182-3. [22] More, Utopia, 229. [23] More, Utopia, 46. [24] More, Utopia, 71. [25] More, Dialogue of Comfort, 179. [26] Lyman Tower Sargent, ‘Ideology and Utopia’ in The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0020. [27] This leads me to address the Erasmus-shaped elephant in the room: what about humanism? Even if Utopia is entirely critical, then the ‘ism’ that might be left standing would be humanism. It’s important to note, however, that humanism has been rather unfortunately named, as scholars agree that it is most definitely not a defined or coherent system of beliefs, but rather a curriculum of learning, an approach to the study of texts and at most a series of questions to which ‘humanists’ provided a variety of answers. One of those question does indeed address the best state of the commonwealth, to which Utopia is a – thoroughly enigmatic – answer. [28] ‘in Utopiensium republica, quae in nostris civitatibus optarim verius, quam sperarim.’ [29] More, Apology, 166. by Blendi Kajsiu

There is a strong tendency to conflate populism and anti-politics. In the media every political actor or party that rejects the political status quo is labelled populist, regardless of their political ideology. In academia, on the other hand, the rejection of the existing political class and institutions is understood as the very essence of populism. According to one of the leading political theorists of populism, Margaret Canovan, ‘in its current incarnations populism does not express the essence of the political but instead of anti-politics.’[1] In similar fashion, Nadia Urbinati argues that anti-politics constitutes the basic structure of populist ideology.[2] Hence, the concept of populism has been ‘regularly used as a synonym for “anti-establishment”’.[3]

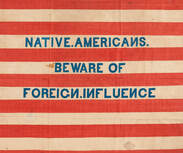

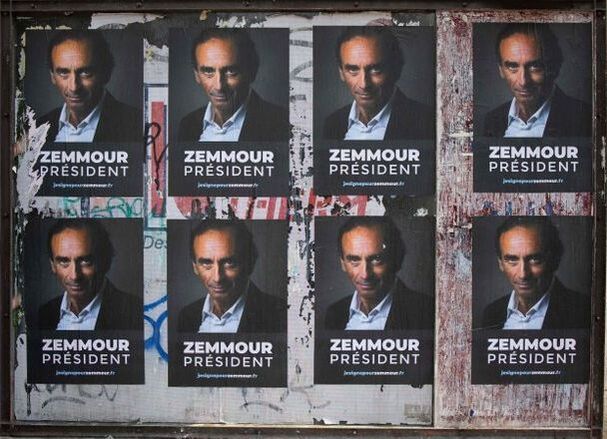

The conflation between populism and anti-politics is understandable given that anti- elitism constitutes one of the core features of populism in its dominant definitions, whether as a thin ideology or as a political logic.[4] In most contemporary populist movements anti- elitism has taken the specific form of anti-politics, whether in the rejection of traditional political parties (la partidocracia) by Alberto Fujimori in Peru, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, or the denunciation of the political establishment by Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece. The traditional political class has also been the main enemy of right-wing neo-populist movements in Latin America.[5] Likewise, dissatisfaction with the political establishment has constituted an important source of right-wing populism in Europe.[6] Hence, the confusion between anti-politics and populism, even when absent theoretically, can easily appear at the empirical level. Yet anti-politics and populism are two distinct phenomena. The rejection of the political status quo, the denunciation of the existing political class and institutions can be articulated from different ideological perspectives. Politics, politicians, and political institutions can be rejected for violating the popular will (populism), for undermining market competition (neoliberalism), for weakening the nation (nationalism), for undermining tradition and family values (conservatism), or for producing deep inequalities and high concentrations of wealth (socialism). Hence, there are populist, conservative, socialist, neoliberal, and liberal anti-political discourses, alongside many others, which combine various ideological perspectives in their rejection of the political class and political institutions. It is only when the rejection of politics, politicians, and the political status quo is combined with key concepts of populism that we can talk of populist anti-politics. Following Mudde, I understand populism as a “thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”[7] The antagonism between the honest people and the corrupt elite, the people as the underdog and the only source of political legitimacy, as well as popular sovereignty, constitute the conceptual core of any populist discourse because they are present in all its historical manifestations. Populism functions as an ideology insofar as it partially fixes the meaning of these concepts in relation to each other. Thus, from a populist perspective, democracy is understood primarily as a direct expression of ‘the’ people’s will rather than as a set of institutional or procedural arrangements (liberal democracy). Popular sovereignty here means that ‘the people are the only source of legitimate authority’. Political legitimacy is defined in terms of the will of the people, as opposed to tradition (conservatism) or procedures (liberalism). Within the people–elite antagonism, the people are defined vertically as the underdog (the plebs) against a corrupt elite. This is different from the horizontal definition ‘the-people-as-nation’ within nationalist ideology, where the people are defined primarily in opposition to non-members rather than against the elite.[8] The last point is important in order to distinguish between populism and nativism. The latter denotes an exclusionary type of nationalism ‘that holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by the members of the native group [….] and that non-native people and ideas are fundamentally threatening to the homogeneous nation-state.’[9] It is normally conflated with populism given that ‘both nationalism and populism revolve around the sovereignty of “the people”, with the same signifier being used to refer to both [“the people” and “the nation”] in many languages (e.g., “das Volk”).’[10] Although in practice these two ideologies are interweaved, they define ‘the people’ in distinctive ways. From a populist perspective, the people is defined vertically as the underdog against an oppressive elite. This is an open-ended definition which implies that all those social groups that are being oppressed by the elite could be part of the people. In other words, the ‘people’ is not defined positively through a fixed set of criteria, as much as negatively in opposition to the corrupt elite. The nativist ideology, on the other hand, defines the people horizontally as a nation in opposition to other nations, cultures, religions, or social groups. This is a closed definition that assigns a set of positive attributes to the people in terms of language, territory, religion, race, culture, or birth. Hence, from a nativist perspective the national elite remains ‘part of the nation even when they betray the interests of the nation and their allegiance to the nation is questioned.’[11] This is not true in the case of populism where ‘the elite’ by definition is not part of the ‘people’. Given that populism as a very thin ideology articulates a very limited number of key concepts, anti-politics can rarely be simply, or even primarily, populist. This is why a number of scholars have argued that although radical right-wing parties in Europe are often labelled populist they are primarily defined by ethnic nationalism or nativism.[12] In other words, their rejection of the existing political class and institutions is more nativist than populist. Yet despite the growing consensus that ethnic nationalism or nativism is the key ingredient of extreme right-wing parties in Europe, they are still labelled populist radical-right parties, and not nationalist or nativist radical-right parties. This is not to say that there cannot be right-wing political parties that articulate anti-politics primarily in a populist fashion, although they are hard to find in Europe. A number of leaders and political movements in Latin America, usually labelled neo-populists, have successfully combined a neoliberal ideology with populism. Presidents Alberto Fujimori in Peru (1990–2000), Carlos Menem in Argentina (1989–1999), and Fernando Collor (1990–1992) in Brazil combined populism and neoliberalism when in office.[13] In all these cases, populism, and not nativism, was the key element of their political articulation. Hence the articulation of populism with nativism in right-wing populist movements is contingent rather than necessary. It appears natural due to the Eurocentrism of most literature on radical right-wing populism, which focuses on Europe and often ignores right-wing populist movements in Latin America and beyond. Our obsession with populism can blind us to the ideological zeitgeist that fuels the current anti-politics. Instead of identifying the populist versus anti-populist cleavage that has supposedly displaced the left–right division, it could be more productive to clarify how ideological polarisation has been producing rejections of current politics, whether along the cosmopolitan–nationalist or the left–right ideological dimensions. Indeed, ideological polarisation along the left–right and the cosmopolitan–nationalist spectrums would tell us a lot more about the 2020 Presidential Elections in the USA than the populist–non-populist cleavage. A focus on nationalism would tell us a lot more about the emergence of radical-right parties in Europe, as well as the rise of extreme right-wing politicians such as Eric Zemmour in France, which mainstream media calls “populist”. Not to mention that populism, unlike nationalism, tells us very little about the current invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Focusing on populism diverts our attention from the multiple ideological dimensions of anti-politics discourses today. The rejection of politics, the political class, and political institutions is rarely developed simply from a populist perspective, especially in Europe. It is often justified in the name of tradition, equality, identity, and especially in the name of the nation. Equating populism with anti-politics tends to obscure the ideological dimension of the latter, especially when populism is understood as a non-ideological phenomenon that lies beyond the left–right spectrum. [1] M. Canovan, The People (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005), 78. [2] N. Urbinati, Me the People: How Populism Transforms Democracy (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2019), 62. [3] J. W. Müller, What Is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 1. [4] See C. Mudde, 'The populist zeitgeist', Government and Opposition 39:4 (2004), 542–563, at p. 543 and E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005). [5] K. Weyland, 'Neopopulism and Neoliberalism in Latin America: Unexpected Affinities', Studies in Comparative International Development 33:3(1996), 3–31, at p. 10. [6] See C. Fieschi & P. Heywood, 'Trust, cynicism and populist anti-politics', Journal of Political Ideologies 9:3 (2004), 289–309; as well as H. G. Betz, ‘Introduction’, In Hans-Georg Betz and Stefan Immerfall (Eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998). [7] C. Mudde, 'The populist zeitgeist', 543. [8] B. De Cleen and Y. Stavrakakis, 'Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism', Javnost – The Public 24:4 (2017), 301–319, at p. 312. [9] C. Mudde, ‘Why nativism not populism should be declared word of the year’, The Guardian, 7 December 2017, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/07/cambridge-dictionary-nativism-populism-word-year [10] B. De Cleen and Y. Stavrakakis, 'Distinctions and Articulations', 301. [11] B. De Cleen, ‘Populism and Nationalism’ in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 342–362, at p. 351. [12] See B. Moffit, ‘The populism/Anti-populism Divide in Western Europe’, Democratic Theory 5 (2018), 1–16; B. De Cleen, ‘Populism and Nationalism’, 349; J. Rydgren, ‘Radical right-wing parties in Europe: What’s populism got to do with it?’, Journal of Language and Politics 16:4 (2017), 485–496. [13] K. Weland, 'Neoliberal Populism in Latin America and Eastern Europe', Comparative Politics 31 (1999), 379–401, at p. 379. by Jan Niklas Rolf

With Russia deploying more than 100,000 troops near the border to Ukraine and China detaining more than 1,000,000 Uyghurs in the region of Xinjiang, Thomas Bach, president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), felt compelled to appeal to the Olympic spirit of peace in his Beijing 2022 opening ceremony speech: “This is the mission of the Olympic Games”, he said, “bringing us together in peaceful competition. Always building bridges, never erecting walls. Uniting humanity in all our diversity”.

Yet, given the US-led diplomatic boycott, there were hardly any officials to engage in the kind of ping-pong diplomacy that Nixon and Mao had practiced fifty years ago. Due to the regime’s strict zero-COVID policy, there were also no foreign spectators in China to make a connection, and the athletes and coaches that actually made it into the country were put in a bubble that prevented them from immersing into the culture. “Building bridges”, thus, seemed to come down to the commentators that bring one of the most televised events in the world into our homes. By analysing the television coverage of the parade of nations during the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing, this post explores how commentators are engaging with other nations. The two TV stations chosen are the public-service broadcaster Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF) and the pan-European network Eurosport 1, both of which are freely available in Germany. As the most successful nation at Olympic Winter Games, Germany has a strong Olympic fan base and, hence, should make for a good case study. But first, we have to establish the link between the Olympics and peace. During the ancient Olympic Games, a truce was proclaimed to allow for a safe journey to and from historic Olympia. In 1992, the IOC renewed this tradition by calling upon all nations to put aside their political differences for the duration of the Games, and invoked it at every Games ever since. While a brief ceasefire during the 1994 Winter Games in Lillehammer allowed for the vaccination of an estimated 10,000 children in Bosnia,[1] Russia’s full-scale invasion of Georgia took place on the day of the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing. The conflict in Ukraine, too, escalated around the time the 2014 Winter Games were held in nearby Sochi. In the face of Russia’s military build-up in the lead-up to the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly unanimously adopted the Olympic Truce Resolution that “Urges Member States to observe the Olympic Truce individually and collectively, within the framework of the Charter of the United Nations, throughout the period from the seventh day before the start of the XXIV Olympic Winter Games until the seventh day following the end of the XIII Paralympic Winter Games, to be held in Beijing in 2022 […].” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine between the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, thus, constituted not only a violation of international law, but also of the Olympic Truce. But even if observed, the Olympic Truce only guarantees a temporary or negative peace. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, was more interested in fostering a sustainable or positive peace: “We shall not have peace until the prejudices which now separate the different races shall have been outlived. To attain this end, what better means than to bring the youth of all countries periodically together for amicable trials of muscular strength and agility?”[2] Like the current IOC president, de Coubertin saw the Games as a locus of encounter where people of different nations get “to know one another better”.[3] Knowledge, in turn, “will replace dangerous ignorance, mutual understanding will soften unthinking hatreds”.[4] Enshrined in the Olympic Charter, which pictures sports as means to “better understanding between each other and of friendship, thereby helping to build a better and more peaceful world”, and the Olympic Truce Resolution, according to which “sports can contribute to an atmosphere of tolerance and understanding among peoples and nations”, this view has taken on an “ossified form” over the years.[5] However, unlike other elements of de Coubertin’s ideological morphology such as athleticism and amateurism, Simon Creak notes, it “has remained remarkably resistant to critical analysis ever since”.[6] This post examines whether commentators are engaging with the ‘other’ in a meaningful way, thereby promoting a deeper understanding of other countries and cultures that the IOC and UN deem critical for a more sustainable peace. To that end, it conducts a discursive analysis of the television coverage of the parade of nations—an integral part of the opening ceremony during which the teams of participating nations parade into the stadium—by the two networks ZDF and Eurosport 1 along the three dimensions of sports, politics and culture. Sports On both networks, the greatest chunk of commentary was on sports. And yet the focus was a very different one. The two ZDF commentators—reporter Nils Kaben and correspondent Ulf Röller—used the nation as a frame of reference, making frequent references to the Olympic record of national teams: We learn that Hungary and Poland have participated in all Winter Games so far, that Norway and Switzerland were particularly successful at the previous Winter Games and that Turkey and Azerbaijan are yet to win their first medals at Winter Games. Where references were made to individual athletes, they tended to be references to flag-bearers as representatives of their respective nations. In contrast, the two Eurosport 1 commentators—reporter Siegfried Heinrich and journalist Birgit Nössing—seemed to follow the mantra of the Olympic Charter that—all appearances to the contrary—the “Games are contests between individuals and not between nations”, telling a number of personal stories: We learn that an athlete from Ecuador does not eat anything before her contests and that another athlete from Andorra always wears different colored FC Barcelona socks during her contests. When the national teams of Brazil and Spain entered the stadium, it was particular athletes that came to the mind of the commentator: “Brazil marches in. And there I’m thinking, if you allow, of the cross-country skier Bruna Moura […]”. “Now comes Spain […]. When I think of Spain, I think of [Francisco Fernández] Ochoa […]. And I have to think of Javier Fernández [López], the figure skater”.[7] The exchange the commentator had with the co-commentator on figure skater Vladimir Litvintsev, flag-bearer of Azerbaijan, is particularly telling in this regard: Co-commentator: “Until 2018, he skated under the Russian flag and then he changed to Azerbaijan.” Commentator: “And why?” Co-commentator: “ROC [Russian Olympic Committee] is the keyword.” Commentator: “Hm?” Co-commentator: “ROC [pause]. Well, the Russians are not allowed [to compete] under their own flag.” Commentator: “No, not only. He changed because the competition in Russia had become too fierce.” Co-commentator: “That’s what you mean.” Commentator: “Yes. He said to himself, I'll go to Azerbaijan, because there I'll have my starting place for sure.” For the co-commentator, Litvintsev’s decision to become an Azerbaijani citizen was governed by the fact that Russia, due to its state-sponsored doping, was banned from the Games, forbidding Russian athletes to compete under the Russian flag. For the commentator, in contrast, it was a rather opportunistic decision that had little to do with not being able to compete under the Russian flag, but with being able to compete at all, no matter under which national flag. Once again, the commentator refused to engage in “methodological nationalism”, that is, to conceive of the nation as the sole unit of analysis.[8] Politics The second most discussed topic after sports was politics. Commentators from both broadcasters commented on the political situation in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Ukraine, Russia and China. In addition, Eurosport 1 commentators mentioned the unrest in Belarus and Kazakhstan. While Eurosport 1 commentators thus made more references to politics, the general tone was more tentative: “And now it’s going to be a bit political, that’s clear. Because now comes Chinese Taipei, that is, Taiwan […]”. “It remains a bit political when we have Hong Kong here […]”. “Ukraine, and things are getting a bit political here too […]”. While in each case the commentators added a few sentences about the political situation before turning the conversation to other issues, the introductory phrase “a bit political” downplayed the import of it. ZDF commentators, in contrast, employed a number of superlatives when talking about politics: “This [the political status of Taiwan] is a super sensitive topic […]. It is the great political goal of Xi Jinping to bring Taiwan back to the mainland and there is a huge political dispute about this with the Americans”. The commentary was also more accusative, emotive and generalising in nature: “The pictures that we recently had to see from Hong Kong [in this moment, the camera captures the political leader of China] for which he, Xi Jinping, is responsible, also shook us to the core”, with the “us” supposedly referring to an assumed national, if not global, community. When the Chinese team entered the stadium, both ZDF and Eurosport 1 commentators talked about the government’s attempt to turn China into a competitive winter sports nation. And yet ZDF commentators were way more negative about this than Eurosport 1 commentators, as can be seen from a comparison of the following two conversations: Commentator (ZDF): “With a lot of effort, with a lot of European trainer know-how, they want to close the gap with the world’s best. Very ambitious [in fact, China was among the three most successful nations at the Games, even outperforming the United States in gold medals].” Co-commentator (ZDF): “Of course, China is not a winter sports nation, but they have bought heavily internationally, and have turned many athletes into Chinese people, given them a Chinese passport to improve the performance of the team.” This patronising (“with a lot of European trainer know-how”) and slightly sinophobic (“turned many athletes into Chinese people”) language can be contrasted with the rather positive and personalised commentary on Eurosport 1: Co-commentator (Eurosport 1): “In order to make China a winter sports nation they are bringing in the best of the best coaches […]. They are supposed to make stars out of the Chinese rough diamonds […]. And then there is Eileen Gu [a US born freestyle skier who competes for China, for which she has attracted a lot of criticism].” Commentator (Eurosport 1): “Well, Eileen Gu, that’s the story par excellence […]. Dad is American. Mom is Chinese. And she said what I think is a really beautiful sentence: Nobody can deny that I’m American, she said, nobody can deny that I’m Chinese, and that’s almost a conciliatory story.” Indeed, by starting for China, Gu hopes “to unite people, promote common understanding, create communication, and forge friendships between nations”. The Eurosport 1 commentator moved on to talk about the Chinese ice hockey team, which is mostly made up of former US-Americans and Canadians, only to conclude with: “But it’s nice that it happens like this”. Culture Surprisingly, culture was the least discussed topic during the carnival of cultures that is the parade of nations. The only time it featured in the ZDF commentary was when the Austrian team, rather coincidentally, entered the stadium to a waltz tune and the commentator, noticing this, commented: “And then there’s a bit of waltz music in the bird’s nest”. But comments on culture were not only sparse; sometimes they were also false. The Eurosport 1 commentator, for example, suggested that, instead of the national anthem, Russian gold medal winners will hear Beethoven’s 9th symphony where, in fact, it was Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto no. 1. On three more occasions, the Eurosport 1 commentator touched upon culture and customs. When the Argentinian team marched into the stadium, he complained: “Well, Argentina. With six participants. I don’t understand that, because there are such great ski areas in Argentina and yet nothing comes out of it that would be remotely competitive athletes.” With the co-commentator not responding, which could be interpreted as a sign of dissent, the commentator came to qualify his statement by attributing the lack of competitive athletes to a different culture: “Not everyone sees sport as the main goal in life, you have to take this into consideration, of course. There are cultures where sport is important, there are cultures where sport is not so important or not that valued.” This is indicative of a learning process that de Coubertin sought to instill in society at large: Being raised in a country that is passionate for (winter) sports, the commentator wonders in quite derogatory terms that a country with favorable conditions does not produce competitive athletes. After some reflection, however, he recognises that there are cultures that might not share his enthusiasm for sports. A similar learning process was evident when the commentators talked about a female athlete from Iran: Commentator: “She is only the third woman from Iran to qualify for the Winter Games. I find that remarkable and very conciliatory when you know how hard women in Iran have to fight for recognition, for sporting recognition.” Co-commentator: “Yes, and she is asked again and again, she said in an interview, are you allowed to ski at all, does your religion allow it and then of course she said that it is no problem at all. Some of the questions she doesn’t even understand. For example, is there snow in Iran and she always says, well, we are not a desert like Saudi Arabia.” Commentator: “That’s probably true”. Whereas the commentator was echoing the Western narrative that women in Iran and other Islamic republics are severely suppressed, the co-commentator, by citing the Iranian athlete, questioned that very narrative and other stereotypes about Iran, which the commentator, by responding with “that’s probably true”, seemed to accept. Lastly, when the flag-bearer of Timor-Leste entered the stadium in traditional clothes, the commentator made an approving comment of the costume. Apparently noting the Orientalism in his words, he added: “I wouldn’t consider it as exotic, it’s just something that one likes to see”. While there was no further discussion of cultural artefacts, commentators did present some geographical facts about what they assumed to be lesser known countries, that is, far-away or small countries, or both. Eurosport 1 viewers learned that Timor-Leste is “an island nation in Southeast Asia near Indonesia” and ZDF viewers got to know that Madagascar is “the second largest island nation in the world by area after Indonesia, located in the Indian Ocean, east of Africa”. The latter audience was also told that San Marino is “a microstate surrounded by Italy” and that Andorra is “a principality in the Pyrenees”. Yet, rather than talking about its peculiarity, Andorra was compared to and lumped together with other European microstates: “By area, the largest of the six European microstates. San Marino, Monaco, Liechtenstein, Vatican City are all among them”. Madagascar, too, was only made sense of by reference to other African countries: “Madagascar, the first of five representatives from Africa”. When the national team of Ghana entered the stadium, the ZDF commentator proclaimed: “Ghana, the next representative of Africa”. Notably, no other teams were pictured as representatives of their respective continent—an expression of the common conflation of African countries with the African continent. The Eurosport 1 commentator, on the other hand, conflated Great Britain with England when he remarked: “In curling, the English, represented by Scotland, have recently beaten the Swedes [...]. The Scots are very important for England”. Strictly speaking, even the official brand name, “Team GB”, is not correct, as the team also includes athletes from Northern Ireland, which does not belong to Great Britain. Yet commentators did not even get some of the more basic facts straight. Nor can commentators be expected to contribute towards a better knowledge of other cultures and countries within the thirty seconds or so that they have when a national team enters the stadium during the parade of nations. What commentators can do, however, is to set the tone. Here, the tentative and reflective tonality of Eurosport 1, focusing on the individual, seems to be more conducive towards cross-cultural understanding and, eventually, positive peace than the affective and accusative tonality of ZDF, applying a national frame. While there was no evidence of assertive nationalism or chauvinism, a national bias was clearly discernible. Indeed, even the Olympic Broadcasting Services (OBS), who, on their website, claim to provide “unbiased” and “neutral” coverage to national broadcasters (who then add their own commentary), were not able to fully deliver on that promise: When the German team entered the stadium, an applauding Thomas Bach—IOC president and German national—was captured by the cameras. When the Portuguese team paraded into the stadium, António Guterres—UN General-Secretary and Portuguese national—appeared on the screen. The same holds true for most of the state leaders—from Albert II of Monaco to Xi Jinping of China—that attended the opening ceremony. However, when the Russian Olympic Committee marched in with Russian flags stitched onto their otherwise neutral jackets, the OBS director—maybe in anticipation of what was yet to come—chose to edit out a cheering Vladimir Putin. [1] H. L. Reid, ‘Olympic Sport and Its Lessons for Peace’, Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 33 (2006), pp. 205-214. [2] Pierre de Coubertin, ‘The Olympic Games of 1896’, Century Magazine 53 (1896), pp. 39-53 at p. 53. [3] Ibid. [4] Pierre de Coubertin, cited in J. J. MacAloon, This Great Symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), p. xxv. [5] Simon Creak, ‘Friendship and Mutual Understanding. Sport and Regional Relations in Southeast Asia’, in B. J. Keys (ed.), The Ideals of Global Sport. From Peace to Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), pp. 21-46 at p. 26. [6] Ibid. [7] All comments have been transcribed and translated by the author. [8] Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller, ‘Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences’, Global Networks 2 (2002), pp. 301-334. by Feng Chen

Ideology has been a central force shaping labour movements across the world. However, the role of ideologies in labour activism in contemporary China has received scant scholarly attention. Previous studies on Chinese labour tend to hold that in China’s authoritarian political context, ideologically driven labour activities have rarely existed because they are politically risky; they also assume that ideologies are only related to organised labour movements, which are largely absent in the country. In contrast to these views, I argue that ideologies are important for understanding Chinese labour activism and, in fact, account for the emergence of different patterns of labour activism.

By applying framing theory, this piece examines how ideologies shape the action frames of labour activism in China. Social movements construct action frames by drawing from their societies’ multiple cultural stocks, such as religions, beliefs, traditions, myths, narratives, etc.; ideologies are one of the primary sources that provide ideational materials for the construction of frames. However, frames do not grow automatically out of ideologies. Constructing frames entails processing the extant ideational materials and recasting them into narratives providing “diagnosis” (problem identification and attribution) and “prognosis” (the solutions to problems). Framing theory is largely built on the experiences of Western (i.e., Euro-American) social movements. When social movement scholars acknowledge that action frames can be derived from extant ideologies, they assume that movements have multiple ideational resources from which to choose when constructing their action frames. Movement actors in liberal societies may construct distinct action frames from various sources of ideas, which may even be opposed to each other. Differing ideological dispositions lead to different factions within a movement. Nevertheless, understanding the role of ideology in Chinese labour activism requires us to look into the framing process in an authoritarian setting. In this context, the state’s ideological control has largely shut out alternative interpretations of events. It is thus common for activists to frame and legitimise their claims within the confines of the official discourse in order to avoid the suspicion and repression of the state. Nevertheless, the Chinese official ideology has become fragmented since the market reforms of the late 1970s and 1980s, becoming broken into a set of tenets mixed with orthodox, pragmatic, and deviant components, as a result of incorporating norms and values associated with the market economy. From Deng Xiaoping’s “Let some people get rich first”, the “Socialist market economy” proposed by the 14th National Congress of the CCP, to Jiang Zeming’s “Three Represents”, the party’s official ideology has absorbed various ideas associated with the market economy, though it has retained its most fundamental tenets (i.e., upholding the Party Leadership, Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought, Socialism Road, and Proletariat Dictatorship) crucial for regime legitimacy. Correspondingly, China’s official ideology on labour has since evolved into three strands of discourse: (1) Communist doctrines about socialism vs. capitalism as well as the status of the working-class. (2) Rule of law discourse, which highlights the importance of laws in regulating labour relations and legal procedures as the primary means to protect workers’ individual rights regarding contracts, wages, benefits, working conditions, and so on. (3) The notions of collective consultation, tripartism, and the democratic management of enterprises. These notions are created to address collective disputes arising from market-based labour relations and maintain industrial peace. These three strands of the official discourse, which are mutually conflicting in many ways, reflect the changes as well as the continuity within Chinese official ideology on labour. Framing Chinese labour ideology The fragmentation of the official ideology provides activists with opportunities to selectively exploit it to construct their action frames around labour rights, which have produced moderate, liberal, and radical patterns of labour activism. To be sure, as there is no organised labour movement under China's authoritarian state, the patterns of labour activism should not be understood in strict organisational terms, or as factions or subgroups that often exist within labour movements in other social contexts. The terms are heuristic, and should be used to map and describe scattered and discrete activities that try to steer labour resistance toward different directions. Moderate activism, while embracing the market economy, advocates the protection of workers’ individual rights stipulated by labour laws, and seeks to redress workers’ grievances through legal proceedings. One might object to regarding this position as ideological—after all, it only focuses on legal norms and procedures. However, from the perspective of critical labour law, it can be argued that labour law articulates an ideology, as it aims to legitimate the system of labour relations that subjects workers to managerial control.[1] Moreover, moderates’ adherence to officially sanctioned grievance procedures restrains workers' collective actions and individualises labour disputes, which serves the purpose of the state in controlling labour. Radical activism is often associated with leftist leanings and calls for the restoration of socialism. Radical labour activists have expressed their views on labour in the most explicit socialist/communist or anti-capitalist rhetoric. They condemn labour exploitation in the new capitalistic economy and issue calls to regain the rights of the working class through class struggle. Unsurprisingly, such positions are more easily identified as ideological than others. Liberal activists advocate collective bargaining and worker representation. They are liberal in the sense that their ideas echo the view of “industrial pluralism” that originated in Western market economies. This view envisions collective bargaining as a form of self-government within the workplace, in which management and labour are equal parties who jointly determine the condition of the sale of labour-power.[2] Liberals have also promoted a democratic practice called “worker representation” to empower workers in collective bargaining. To make their action frames legitimate within the existing political boundaries, each type of activist group has sought to appropriate the official discourse through a specific strategy of “framing alignment”.[3] Moderate Activism: Accentuation and Extension Accentuation refers to the effort to “underscore the seriousness and injustice of a social condition”.[4] Movement activists punctuate certain issues, events, beliefs, or contradictions between realities and norms, with the aim of redressing problematic conditions. Moderate labour activists have taken this approach. Adopting a position that is not fundamentally antagonistic to the market economy and state labour policies, they seek to protect and promote workers’ individual rights within the existing legal framework, and correct labour practices where these deviate from existing laws. Thus, their frame is constructed by accentuating legal rights stipulated by labour laws and regulations and developing a legal discourse on labour standards. Moderate activists’ diagnostic narrative attributes labour rights abuses to poor implementation of labour laws, as well as workers’ lack of legal knowledge. Their prognostic frame calls for effective implementation of labour laws and raising workers' awareness of their rights. Extension involves a process that extends a frame beyond its original scope to include issues and concerns that are presumed to be important to potential constituents.[5] Some moderate activists have attempted to extend workers’ individual labour rights to broad “citizenship rights”, which mainly refer to social rights in the Chinese context, stressing that migrant workers’ plight is rooted in their lack of citizenship rights—the rights only granted to urban inhabitants. They advocate social and institutional reforms for fair and inclusionary policies toward migrant workers. While demand for citizenship rights can be seen as moderate in the sense that they are just an extension of individual rights, it contains liberal elements, because such new rights will inevitably entail institutional changes. To extend rights protection beyond the legal arena, moderate activists are instrumental in disseminating the idea of “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) and promoting it to enterprises. This aims to protect workers’ individual rights by disciplining enterprises and making them comply with labour standards. Liberal Activism: Bridging Frame bridging refers to the linking of two or more narratives or movements that have a certain affinity but have been previously formally unconnected. While the existing literature has paid more attention to “ideologically congruent but structurally unconnected frames regarding a particular issue or problem”,[6] “bridging” can also be understood as a means of “moral cover”.[7] That is, it splices alternative views to the official discourse, as a way of creating legitimacy for the former. This is a tactic that China’s liberal labour activism has used fairly frequently. Liberals support market reforms and seek to improve workers’ conditions within the current institutional framework, but they differ from moderates in that their diagnostic narrative attributes workers’ vulnerable position in labour relations to their absence of collective rights. Meanwhile, their prognostic narrative advocates collective bargaining, worker representation, and collective action as the solution to labour disputes. The ideas liberal activists promote largely come from the experiences of Western labour movements and institutional practices. As a rule, the Chines government regards these ideas as unsuited to China’s national conditions. To avoid being labelled as embracing “Western ideology”, liberal activists try to bridge these ideas and practices with China’s official notions of collective consultation, tripartism, and enterprise democracy, justifying workers’ collective role in labour disputes by extensive references to the provisions of labour laws, the civil law, and official policies. These are intended to legitimise their frame as compatible with the official discourse. Radical Activism: Amplification Amplification involves a process of idealising, embellishing, clarifying, or invigorating existing values or beliefs.[8] While the strategy may be necessary for most movement mobilisations, “it appears to be particularly relevant to movements reliant on conscience constituents”.[9] In the Chinese context, radical activists are typically adherents of the orthodox doctrines of the official ideology, either because they used to be beneficiaries of the system in the name of communism or they are sincerely committed to communist ideology in the Marxist conception. Unlike moderates and liberals, who do not oppose the market economy, radicals’ diagnostic frames point to the market economy as the fundamental cause of workers’ socioeconomic debasement. They craft the “injustice frame” in terms of the Marxian concept of labour exploitation, and their prognostic frame calls for building working-class power and waging class struggles. Although orthodox communist doctrines have less impact on economic policies, they have remained indispensable for regime legitimacy. Radical activists capture them as a higher political moral ground on which to construct their frames. Their amplification of the ideological doctrines of socialism, capitalism, and the working class not only provide strong justification for their claims in terms of their consistency with the CCP’s ideological goal; it is also a way of forcefully expressing the view that current economic and labour policies have deviated from the regime’s ideological promises. Conclusion These three action frames have offered their distinct narratives of labour rights (i.e., in terms of the individual, collective, and class), and attributed workers’ plights to the lack of these rights as well as proposing strategies to realise them. However, this does not mean that the three action frames are mutually exclusive. All of them view Chinese workers as being a socially and economically disadvantaged group and stress the crying need to protect individuals’ rights through legal means. Both moderates and liberals support market-based labour relations, while both liberals and radicals share the view that labour organisations and collective actions are necessary to protect workers’ interests. For this reason, however, moderates have often regarded both liberals and radicals as “radical”, as they see their conceptions of collective actions as fundamentally too confrontational. On the other hand, it is not surprising that in the eyes of liberals, radicals are “true” radicals, in the sense that they regard their goals as idealistic and impractical. It is also worth noting that activist groups have tended to switch their action frame from one to another. Some groups started with the promotion of individual rights but later turned into champions for collective rights. The three types of labour activism reflect the different claims of rights that have emerged in China’s changing economic as well as legal and institutional contexts. While the way that labour activists have constructed their frames indicates the common political constraints facing labour activists, their emphasis on different categories of labour rights and strategies to achieve them demonstrates that they did not share a common vision about the structure and institutions of labour relations that would best serve workers’ interests. The lack of a meaningful public sphere under tight ideological control has discouraged debates and dialogues across different views on labour rights and labour relations. Activists with different orientations have largely operated in isolation, and often view other groups as limited and unrealistic—a symptom of the sheer fragmentation of Chinese labour activism. Yet the evidence shows that, although they have resonated with workers to a varying degree, these three patterns of activism have faced different responses from the government because of their different prognostic notions. Both liberal and radical activism have been met with state suppression, because of their advocacy of collective action and labour organising. Their fate attests to the fundamental predicament facing labour movements in China. [1] For this perspective, see J. Conaghan, ‘Critical Labour Law: The American Contribution’, Journal of Law and Society, 14: 3 (1987), pp. 334-352. [2] K. Stone, ‘The Structure of Post-War Labour Relations’, New York University Review of Law and Social Change, 11 (1982), p. 125. [3] R. Benford and D. Snow, ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment’, Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp. 611–639. [4] S. Tarrow, Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012). [5] R. Benford and D. Snow, ‘Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment’, Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp. 611–639. [6] Ibid. [7] D. Westby, ‘Strategic Imperative, Ideology, and Frames.” In Hank Johnstone and John Noakes (Eds.), Frames of Protest (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), pp. 217–236. [8] R. Benford and D. Snow, “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000), pp.611–639. [9] Ibid. by Noam Hadad and Yaacov Yadgar

How are we to understand a self-proclaimed “religious-nationalist” ideology if we take seriously the critical insights of a wide field of studies that question the very meaning of and distinction between the two organs of this hyphenated identity (i.e., religion and the supposedly secular nationalism)?